Abstract

In recent years, an increasing ‘emotionality’ in Britain’s political discourse has been attested by many researchers and public commentators alike, regularly accusing alleged modern-day ‘populists’ of having caused this emotionalization with their unusual conduct and rhetoric. In these analyses, however, emotional speech is too often conflated with ‘populist’ speech, without offering substantial historical proof to support such claims. To scrutinize this alleged novel emotionalization of the general political discourse in Britain and to historically contextualize the influence that alleged ‘populists’ have had on it, I conducted a comparative, sequential mixed methods study of political speeches from British Labour and Conservative Party leaders (quant → QUAL), performing a manual neopragmatist discourse analysis as well as an automated dictionary analysis. With this approach, I was able to determine the distinct argumentative characteristics of the speeches and explore the discourses’ emotional quality, reporting a multitude of qualitative and quantitative differences as well as similarities between the two parties. Thus, the paper offers a (historical) overview of the general employment of emotion within political speech and consequently, argumentation used by British politicians. These findings are then used to contextualize claims about the influence that alleged ‘populists’ have had on the emotionality of recent politics.

Introduction

In recent years, growing attention from researchers, media outlets, and the general public has been directed at the (perceived) ‘novel emotionality’ of ‘Western’ politics and the acceleration of this process through the activities of alleged modern-day ‘populists’ (see e.g. Bos et al., Citation2020; Gárdos-Orosz & Szente, Citation2021; Kenny, Citation2018 Lewis et al., Citation2019-2; Lewis et al., Citation2019-1;).Footnote1 Donald J. Trump, leader of the Republican Party and president of the United States of America, was one of the ‘identified patients’ in these public and academic debates that were trying to locate the spark that ignited this ‘novel emotionality’ (cf. Bartscherer, Citation2021; Bateson et al., Citation1956). Similar to the discussion around Trump in the U.S., alleged ‘populist culprits’ were also identified within British political discourse, of which high-ranking mainstream party politicians such as Boris Johnson (Conservative Party leader, Prime Minister), or Jeremy Corbyn (Labour Party leader) (see e.g. Browning, Citation2019; Clarke, Citation2020; De Vries, Citation2016 Watts & Bale, Citation2018;). In academic analyses and public discussions of this ‘newfound emotionality’ since, the term ‘populist’ and ‘emotional’ have commonly been conflated or, at the very least, often associated with one another: ‘populist’ speech is usually considered to be emotional speech and vice versa. However, when one tries to establish what constitutes this new (emotional) ‘populism’ and how it has supposedly influenced the emotionality of the overall political discourse, there is a lack of concrete definitions (cf. Moffitt & Tormey, Citation2014: 382). Instead, most commonly, the (diffuse) notion being propagated by existing ‘populism’ approaches, is that there is a uniqueness to the emotional quality of this (modern-day) ‘populism’. Yet no substantial historical proof is put forward to support their claims (see e.g. Arroyas Langa et al., Citation2019, Bonikowski & Gidron Citation2016, Bos et al., Citation2020, Browning, Citation2019; De Blasio & Sorice, Citation2019; Hidalgo Tenorio et al., Citation2019; Laclau, Citation2005; Lowndes, Citation2015, Molyneaux & Osborne, Citation2017, Panizza, Citation2005, Salmela & von Scheve, Citation2018, Whiteley et al., Citation2019).

To aid researchers invested in estimating the alleged increased ‘emotionality’ of the political debate in Britain and to help those particularly interested in the role that ‘populism’ has played and continues to play within it, a standardized, comparative longitudinal analysis contextualizing said emotionality within a broader historical timeframe certainly seems indicated. After outlining my theoretical framework, in which I offer a conceptualization of political, as well as emotional speech, I will elaborate on my methods used to investigate the overall emotional quality of the British political discourse. The ensuing analysis provides the backdrop for my analysis of the supposed uniqueness and influence of modern-day ‘populism’. The two-method approach enables me to provide a general overview of trends in emotionality of the British political discourse over the past century. I do so by locating specific affective quantifiers within a sample of speeches from party leaders, using the example of the two main parties (Conservative and Labour). The in-depth qualitative analysis of the argumentation of some of these speeches was conducted using neopragmatist discourse analysis. I also examine a list of potential ‘populist’ identifiers that were deduced in a previous study on U.S. politics (see Bartscherer, Citation2021) and test their translatability to alleged British ‘populists’.

In this paper, I provide a (historical) overview of the general employment of emotion within the political speech and thus the argumentation of British politicians. This overview is intended to identify potential argumentative peculiarities and ‘emotional conventions’ of the two main parties. It is further intended to help contextualize and evaluate existing notions about the uniqueness of modern-day ‘populist’ emotionality and its influence on the general political discourse. However, I am not attempting to formulate yet another definition of what constitutes modern-day ‘populism’. Rather, the study should be seen as a contribution to the fields of political sciences, British politics, rhetoric, populism research, French Pragmatism, and those fields interested in quantitatively supported qualitative research, such as critical discourse analyses.

The research questions underpinning the study were:

What trends can be detected in the samples regarding the ‘emotionality’ of the British political discourse over the course of the past century?

What are the argumentative patterns and peculiarities of British Conservative and Labour Party leaders?

What do these ‘trends in emotionality’ (1) and ‘argumentative conventions’ (2) in British politics tell us about the most recent (suspected) spike in the emotionality of political speech and the impact that alleged modern-day ‘populists’ have had on it?

My data indicates that overall, political discourse in Britain has continuously grown more ‘positive’ since 1900. Within the discourse, emotion has been a volatile, yet continuous component over the past century. It predominantly appears within ‘weaker’ arguments, seemingly as an ‘enhancement’ and has been employed by all speakers throughout the entire timeframe, Labour or Conservative, whether allegedly ‘populist’ or not. I additionally show that, in the context of the past century, modern-day politicians seen as possessing ‘populist’ traits have had indeed a specific, but not a ‘unique’ nor ‘novel’ way of employing emotion within their speeches. I argue this, since their ‘specific’ employment pattern was identified within three other instances in the historical timeframe, all of which were defined by drastic societal changes, (civil) pushes for modernization, political scandal and ‘polarizing political tactics’ (cf. Black, Citation2017; Fisher & Fisher, Citation2009; Maslin, Citation2007). To label some politicians in these periods (including the most recent ones) as ‘populist’ and pinning the emotionalization of the political discourse solely onto them (despite other politicians in the same period exhibiting similar patterns), seems historically unjustified and begs the question as to how helpful such a categorization truly is. I conclude that the employment of emotion in the British political discourse has been present (to varying degrees) in all politicians’ speeches and not exclusive to the speech of speakers with alleged ‘populist’ traits.

I would therefore like to invite researchers and the general public interested in the subject of emotional (political) speech, to learn about its functional complexity, its different (neurological) implications, as well as its historical context, especially when using it as proof positive in the classification (and dismissal) of a handful of ‘populist’ politicians. To revisit the initial sentiment: while all political speech appears to be emotional speech, emotional political speech is not always ‘populist’ speech.

Theoretical background: conceptualizing political and emotional speech

To determine the argumentative peculiarities of the British political discourse, I conducted a computerized, manual neopragmatist discourse analysis, which is designed to provide a standardized path to identifying actors’ distinct argumentative strategies (i.e. the specific combinations of orders of worth/suggestive actions employed by them), their argument formations (up-valuing/down-valuing), as well as their overall argumentative patterns, particularly when analysing situations of political dispute (see Bartscherer, Citation2021). According to this approach, political speech is to be understood as a verbal exchange of arguments by political actors in a public situation of dispute (within the political sphere), with the involved actors’ implicit intention to justify their plans or actions to an (unspecified) audience (see Bartscherer, Citation2021; Boltanski & Thévenot, Citation1999, Citation2006).Footnote2 The approach is based on the Pragmatic Sociology of Critique (PSC) according to Boltanski and Thévenot (see Boltanski & Thévenot, Citation1999, Citation2006; Lemieux, Citation2014, pp. 157–158).However, it diverts from the PSC in three major ways, as it extends the PSC’s theory and therefore its analytical framework. This is achieved firstly, through the introduction of suggestive actions, which are added as additional analytical subcategories alongside the regime of public justification’s eight orders of worth, where any kind of dispute is being negotiated according to the original framework. Just as the orders of worth represent specific motives of valuing subjects and objects in question, these suggestive actions represent the inner rationales of the three remaining action regimes (i.e. regime of violence, regime of routine and regime of love or agape) (see Bartscherer, Citation2021 for further reading).Footnote3 They are intended to account for actors’ (past and future) references to these rationales, when justifying themselves and their actions in situations of verbal dispute (see Bartscherer, Citation2021; Boltanski, Citation2012; Boltanski & Thévenot, Citation1999, Citation2006).Footnote4

Secondly, this approach offers the possibility to systematically catalogue the way arguments are being phrased, and therefore to record which specific argument formation is being employed. The term ‘argument formation’ describes the logical arrangement of an argument, and, thus, in which ‘direction’ (positive/regular or negative/inverted) an actor has employed the different orders of worth/suggestive actions to construct their argument, either up-valuing or down-valuing a subject or object of dispute. Consequentially, allowing researchers to estimate and comment on the overall sentiment or atmosphere of a speech (e.g. overtly negative).

Thirdly, through the incorporation of a hand-curated neurolinguistic dictionary of highly arousing emotive words, the approach enables analysts to determine the roles these specific categories of emotion play within the argumentation of (political) actors. By applying this approach, it is possible, on one hand, to identify the unique combination of orders of worth/suggestive actions that make up actors’ argumentations and, on the other hand, to detect when and where emotion is being employed within them (see Bartscherer, Citation2021). This neopragmatist approach is intended to help approximate the PSC further towards a model that allows for the analysis of real-life situations of verbal dispute, with all its references, especially those lying outside the purely ‘rational’ and complex nature of the already existing orders of worth (cf. Boltanski, Citation2012, pp. 37–38; 42).

Moving onto the subject of how to define ‘emotional speech’, I draw on the findings from neuroscientific research studying human ‘emotions’Footnote5 (see e.g. Bradley & Lang, Citation1999; George & Dane, Citation2016, Kensinger, Citation2007; Kousta et al., Citation2011; Miczek, Citation2007; Moore & Oaksford, Citation2002; Miczek, Citation1994, Phelps & Whalen, Citation2009; Phillips et al., Citation2014; Schultebraucks et al., Citation2016; Warriner et al., Citation2013; Zheng et al. Citation2017) and in particular, on those studies investigating the importance of (negative) sentiments and (specific) emotional stimuli for human perception, attention, learning, reasoning, and memory processes, their inherent understanding of ‘emotional speech’ as being made up of (specific) sets or categories of emotive words. These have been adapted for this study (see e.g. Kensinger, Citation2007; Kousta et al., Citation2011; Miczek, Citation1994 Miczek, Citation2007; Moore & Oaksford, Citation2002; Phelps & Whalen, Citation2009; Phillips et al., Citation2014; Schultebraucks et al., Citation2016; Tyng et al., august 24, Citation2017; Warriner et al., Citation2013;).

Since I am analysing over a century’s worth of political speeches, comparing each speech’s ‘emotionality’ by identifying it through the employment of specific sets of emotive words, their affective stability, is naturally of high importance. To date, this has not been a significant topic of debate within the neurosciences and the neurolinguistics. Emotive words, thus far collected in specific dictionaries (e.g. Bartscherer, Citation2021; Bestgen & Vincze, Citation2012; Bradley & Lang, Citation1999; Warriner et al., Citation2013), are generally not considered to be time-sensitive regarding the emotional response (i.e. the emotions) they evoke. Nevertheless, despite single words potentially changing their meaning and/or the dimensional impact they have on respondents over time, the here adapted approach offers a simple solution to potential issues arising from this, as I am looking to identify emotional categories consisting of hundreds of words within a text, and not one specific word. The likeliness of all the words belonging to a category changing all their meanings, is small to none.Footnote6

Methodology: trend analysis and computerized neopragmatist discourse analysis

I conducted a sequential mixed methods study, a ‘mixed-model analysis’, in two phases using two samples (quant → QUAL) (Creamer & Ghoston, Citation2013, pp. 113–114; Kuckartz, Citation2014, p. 148). The first phase consisted of an automated quantitative content analysis (dictionary analysis) of a large text sample of political speeches (sample1), scanning them for the appearance of highly arousing emotive words and sentiments. This was followed by a trend analysis of the collected data by computing the Mann-Kendall test. The second phase consisted of a manual neopragmatist discourse analysis of a smaller sample (sample2) taken from the first sample, to determine each of the speeches’ explicit argumentative structures and potential patterns arising from them.

Material: why party leader speeches?

To ascertain the role(s) of emotion in the British political discourse over the past century, ample and highly diverse material from varying parties could potentially be investigated. However, within this study I concentrated my efforts on analysing a sample of speeches from Conservative and Labour Party leaders. The main reason for this choice was the comparability this selection grants, when investigating such an extended period of time. Additionally, this focus allowed the inclusion of ‘several strands of political inquiry’, including but not limited to a party’s ‘political institutions, ideology and beliefs, and strategic action’ (cf. Finlayson & Martin, Citation2008, p. 447).Political speeches are designed to inspire their audience and to convince potential sceptics, thereby belonging to the ‘symbolic ritual dimension’ of politics as well as the ‘strategic realist dimension’ (cf. Finlayson & Martin, Citation2008, p. 448). Studying the rhetoric of political speeches, consequentially allowed me to explore these dimensions (cf. Finlayson & Martin, Citation2008, p. 450). As Finlayson and Martin (Citation2008) further elaborate, political speeches can be understood as an ‘attempt to provide others with reason for thinking, feeling or acting in some particular way; to motivate them; to invite them to trust one in uncertain conditions; to get them to see situations in a certain light’ (cf. Finlayson & Martin, Citation2008, p. 450). In short: they are documentations of politicians’ public justifications and their efforts to convince their audiences, and thus according to Boltanski, represent ongoing moments of (verbal) dispute. Per definition, such material would be ideal for an investigation using a neopragmatist discourse analysis, as planned in this study (cf. Finlayson & Martin, Citation2014, p. 4).

Amongst the various forms of political speech-making in Britain, it is particularly the annual speech of the party leader to the party conference that stands out, as it constitutes a ‘ritualized moment of UK politics’, a recurring moment in the British political discourse (cf. Finlayson & Martin, Citation2008, p. 448). These conference speeches made up the main corpus for the study. They were selected preferentially due to their (extensive) length, uninterrupted argumentation, and the fact that they have been historically well recorded, with usually only one speech per year given, thus providing highly distilled summaries of the parties’ political ideologies and strategies, or at the very least, what the party leader tried to convince their party base of (cf. Finlayson & Martin, Citation2014, pp. 445–446). In addition, and in case those types of speeches could not be obtained, they were substituted with party leaders’ speeches in parliament, as those are also seen as ‘a series of ritualized ‘speech moments’’ that follow a very specific form (cf. Finlayson & Martin, Citation2008, p. 448).

Samples of speeches

The sample for the quantitative phase of the study (sample1) consists of semi-public speeches that were given exclusively by party leaders at either, official party conferences and national conventions, or in the House of Commons of the British Parliament (cf. Finlayson & Martin, Citation2014, pp. 446–447). Beginning in 1900 and ending in 2019, I selected one speech per party every two years, except for the last set of speeches from 2019 [1902, … 2014, 2016, 2019] (see ). This was owed to the pandemic-related unavailability of material for 2020 at the time of my analysis. In total, sample1 therefore consists of 120 speeches, i.e. 60 speeches per party with 274,334 words (Conservatives) and 272,637 words (Labour) overall. The types of speeches were distributed as follows:

Table 1 . Distribution of Speeches in sample1.

For the qualitative study, I created a smaller sample (sample2), taking one speech every twenty years from sample1, except for the last speech from 2019 [1900, 1920, … 2000, 2019] (see ). This interval was chosen to ensure a manageable sample-size. Sample2 thus consists of a total of 14 speeches, i.e. seven speeches per party all together with 34,059 words (Conservatives) and 25,192 words (Labour). They are distributed as follows:

Table 2 . Distribution of speeches in sample2.

Analysing ‘Emotional (Political) Speech’

Stevenson et al. (Citation2007) identified two main neuroscientific approaches towards analysing emotional speech: either by using a dimensional approach (by looking at the arousal, dominance, and valence ratings of emotive words) or a categorical approach (by looking at concrete emotional categories, such as e.g. ‘anger’, ‘fear’, etc. that the words belong to) (cf. Stevenson et al., Citation2007, pp. 1020–1021).Footnote7 Following their advice on improving the informative values of emotive words by combining both dimensional and categorical approaches, I manually created a neurolinguistic dictionary sourcing emotive words from one of the largest collections of English lemmas to date (see Bartscherer, Citation2021; Stevenson et al., Citation2007 Warriner et al., Citation2013;). These words were assorted into three categories of either ‘sex’, ‘fear’, or ‘violence’ (categorical distinction), due to their associated stimuli having specific neurological implications, commanding the receivers’ attention (see exogenous attention and ‘attentional bias’, see e.g., Imbir et al., Citation2019), thereby functioning as automatic emotional highlighters within verbal communication (see e.g. Baird et al., Citation2004; Carretié, Citation2014; Clark, Citation2010; Freeman & Ingbretsen, Citation2014; Hamann, Citation2005; Hamann et al., Citation2004; Jarymowicz & Imbir, Citation2015; Phillips et al., Citation2014; Reisberg & Hertel, Citation2004 Schultebraucks et al., Citation2016; Sennwald et al., Citation2015; Sturm, Citation2009; Tyng et al., august 24, Citation2017; Victor et al., Citation2015; Vuilleumier, Citation2005;). My chosen categorical distinction inherently selected those emotive words from the overall corpus that had the highest arousal ratings (additional dimensional distinction). This selection of emotive words as well as a dictionary for sentiment analyses by Hu and Liu (Citation2004), were the specific affective quantifiers chosen to (automatically) identify ‘emotional (political) speech’ within this study’s sample of speeches.

Phase 1: quantitative study – dictionary-based trend analysis (quant)

Using the dictionary of highly arousing emotive words (see Bartscherer, Citation2021), as well as the dictionary for sentiment analysis according to Hu and Liu (Citation2004), I performed an automated quantitative content analysis of sample1 to create time series for the ensuing trend analysis. Separated into the two document groups (‘Conservative Speeches’ and ‘Labour Speeches’) and sorted according to the year they were given in generated lists indicating the total amount of words from both dictionaries appearing in each of the 120 speeches, as well as their percental coverage of each of the individual speeches (in relation to the speeches’ overall words).

I then tested the time-series, by computing the Mann-Kendall test according to Hirsch et al. (Citation1982), using R. The test is intended to detect a monotonic trend in time series data sets and does not require complete records, nor prespecified times of change (cf. Hirsch et al., Citation1982, p. 108). It therefore suits the type of data in both selected samples. The null hypothesis, H0, states that the data is a sample of random variables, distributed independently and identically, and therefore no trend can be detected in the dataset (cf. Hirsch et al., Citation1982, pp. 108–109). The alternative hypothesis H1 states that the distribution of the variables is not identical for all and that a trend can be detected in the dataset (cf. Hirsch et al., Citation1982, pp. 108–109). To reject the null hypothesis, indicating a monotonic trend, the p-value must be < 0.05. If τ is of a positive value, it indicates an ‘upward trend’; if τ is of a negative value, it indicates a ‘downward trend’ (cf. Hirsch et al., Citation1982, p. 109).

Phase 2: qualitative study – neopragmatist discourse analysis (QUAL)

In the second phase, I performed a manual computerized neopragmatist discourse analysis on sample2. The sample was coded manually according to the model, using QDA software. Each speaker’s arguments were coded by identifying the underlying orders and objects of worth, as well as the suggestive actions. Actors’ argument formations (up-/down-valuing) were indicated by assigning differing weights to each of the thus coded segments.Footnote8 Additionally, all speeches from sample2 had been automatically coded with the sentiment dictionary and the dictionary of highly arousing emotive words. These automatically coded segments were then manually screened for potential context-related contra-indications such as double meaning of words. Coded segments that did not represent the decisive meaning of the categories within the speeches were deleted accordingly. Graphs depicting the code-relations and the codes’ distribution throughout each document were then created using the according function in the QDA-software. These graphs provided the basis for my analysis and interpretation of the data and allowed me to debate both parties’ argumentative peculiarities and patterns, as well as the rhetorical contexts for the employment of sentiments and highly arousing emotive words.

Results

Phase 1: Quantitative study (quant) – trends in emotionality

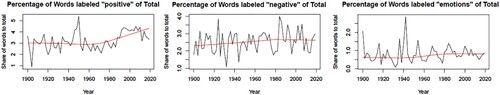

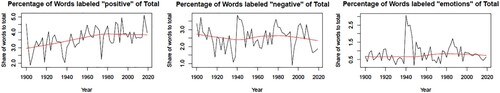

For the interpretation of the following results, it needs to be understood that the time series data sets created from sample1, using both dictionaries, did not undergo any manual data-cleaning processes, unlike the automated codings created with the dictionaries mentioned in the qualitative phase of the study (sample2). Due to the automated word-counting process, some deviations were identified between the auto-counted words versus the manually coded words and segments. However, these deviations were largely negligible, except for two categories: ‘sexual’ and ‘frightening stimuli’, which saw a clearly identifiable decrease in their overall count after deleting ‘falsely’ auto-coded words in the qualitative study phase. Nevertheless, both categories’ overall distribution was not affected fundamentally, with the total n of words counted from the category of ‘sex’ still making up the least amount of words, and those from the category ‘fear’ following second.Footnote9 After careful consideration of the implications of these deviations and the purpose of the first phase of my study (i.e. to contextualize the findings from the qualitative phase), I decided to go ahead with the trend analyses of the two created time-series data sets (comparing the percentage of the speeches covered by the indicated words) for each party. I computed the Mann-Kendall test in R, with the following results (sample1) (see and ):

Table 3 . Results from Mann-Kendall trend test for Labour Party speeches from sample1.

Table 4 . Results from Mann-Kendall trend test for Conservative Party speeches from sample1.

For both, the British Labour and the Conservative Party, I was able to confirm an upward monotonic trend regarding the increase in their speeches’ percental coverage of words with a positive sentiment (see Tables 3 and 4). The null-hypothesis H0 was therefore rejected and the alternative hypothesis H1 accepted. However, the detectable changes in the data-values over the timespan in question (1900–2019) in all other categories (‘negative words in per cent’, ‘all emotive words in per cent’, ‘words labelled ‘sex’ in per cent’, ‘words labelled ‘fear’ in per cent’,’words labelled ‘violence’ in per cent’) did not follow any monotonic trends, which led to the confirmation of the null-hypothesis H0 in all of the other analysed categories (no trends).

Phase 2: qualitative study (QUAL) – argumentative conventions

Labour party – overall argumentative pattern (1900–2019)

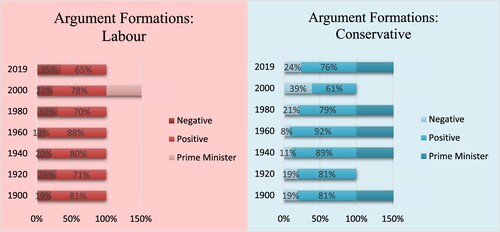

When examining the overall distribution of the arguments (i.e. orders of worth and suggestive actions) and the argument formations throughout the analysed Labour Party speeches (sample2; Table 2), I found that the speakers of the Labour Party mainly employed arguments and objects from the Civic Order (n = 644), followed by the Industrial Order (n = 535), the Inspired Order (n = 316), the Logic/Threat of Violence (n = 297), and the Market Order (n = 259). Labour’s argument formations were predominantly positive/regular; however, in direct comparison to the Conservative Party, their speakers appear to have employed more negative/inverted rationales in their argumentation overall (see ).

When inspecting the distribution of sentiments in the larger sample (sample1; Table 1), positive sentiments outnumbered negative sentiments in Labour’s speeches by nine per cent. Furthermore, the most employed emotional stimuli within all analysed Labour Party speeches from sample1 were violent stimuli (67 per cent of total employed stimuli – Labour), making up 0.55 per cent of all coded words of Labour’s speeches. The other two stimuli nevertheless also appeared within their speeches, with frightening stimuli (28 per cent of total employed stimuli – Labour) in second place, making up 0.25 per cent of all coded words, followed by sexual stimuli (five per cent of total employed stimuli – Labour), making up 0.05 per cent of all coded words.

Emotional stimuli and sentiments both usually appeared in connection with main arguments (i.e. arguments based on a single order of worth) and ‘argumentative compromises’ (i.e. more complex argumentative structures consisting of multiple orders of worth and suggestive actions). However, both these affective quantifiers appeared slightly more frequently (four out of seven speeches), in connection with the larger argument-clusters, indicating weaker ‘argumentative compromises’ (see Boltanski & Thévenot, Citation2006, pp. 278–281).

Conservative party – overall argumentative pattern (1900–2019)

The four most employed arguments in the analysed speeches from the leaders of the Conservative Party (sample2) show an identical succession when compared to Labour’s speeches. They also stem from the Civic Order first (n = 605), the Industrial Order second (n = 532), the Inspired Order third (n = 350), and the Logic/Threat of Violence fourth (n = 343).Footnote10 The fifth most employed order of worth by Conservative speakers is however not the Market but the Domestic Order (n = 280). Conservative speakers’ argument formations were also predominantly positive/regular. Even in the larger sample (sample1), positive sentiments also clearly outnumbered negative sentiments by 16 per cent. The most employed emotional stimuli within this larger sample were – by a large margin – violent stimuli (73 per cent of total employed stimuli by Conservative speakers) making up 0.61 per cent of all coded words of the Conservatives’ speeches, followed by frightening stimuli (23 per cent of total employed stimuli – Conservative) making up 0.21 per cent of all coded words, and a few sexual stimuli (four per cent of total employed stimuli – Conservative) making up 0.07 per cent of all coded words.

Emotional stimuli and sentiments – just like within the Labour Party speeches – appeared in connection with both main arguments and ‘argumentative compromises’ (see Boltanski & Thévenot, Citation2006, pp. 278–281). However, these types of affective quantifiers appeared unequivocally more often (seven out of seven speeches) in connection with the weaker and less convincing ‘argumentative compromises’, instead of the politicians’ main arguments (three out of seven speeches). Overall, Conservative speakers employed sentiments roughly three per cent more often than their Labour Party counterparts.Footnote11

A Century of british political speech – differences and similarities between the two parties

By juxtaposing Labour’s and Conservatives’ argumentative peculiarities, it becomes quite apparent that simply on a quantitative level, their argumentations appear relatively similar, with the orders of worth, suggestive actions, as well as the analysed affective quantifiers (violent, frightening, and sexual ‘emotional stimuli’; ‘positive sentiment’, ‘negative sentiment’) only showing slight deviations in their application throughout the samples (i.e. Conservative speakers employing the Threat/Logic of Violence only 46 times more often than Labour speakers).

The most noteworthy quantitative differences appeared in the distribution and arrangement of highly arousing emotive words within their speeches: with Labour showing a slightly more balanced application of a combination of violent and frightening stimuli, whereas Conservatives also applied said combination, but placed an even larger focus on violent stimuli (see Conservative: 0.61 per cent coverage of their speeches with violent stimuli vs Labour: 0.55 per cent violent stimuli). Both parties’ use of sexual stimuli was miniscule. Conservative speakers therefore seem to have employed an argumentation that is more focused on violent stimuli than that of their Labour counterparts.

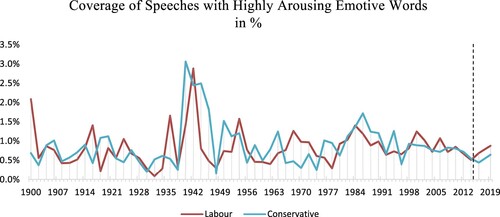

Despite detectable increases and decreases in the coverage of all speeches with affective quantifiers in sample1, the Mann-Kendall test confirmed a monotonic trend only for the detected increase of positive sentiments, for both the Conservative and the Labour Party. My analysis therefore suggests that the speeches by British party leaders have gradually and consistently become ‘more positive’ over the course of the last century (see and ).Footnote12 Moreover, all analysed speeches contained continuous levels of highly arousing emotive words, from the very beginning of the set timeframe to its very end (see ). Conservative Party speakers overall showed a marginally higher application rate of these highly arousing emotive words, with an overall 0.87 per cent coverage of their speeches versus 0.85 per cent of all analysed Labour speeches. These continuous levels of emotional stimuli within both parties’ speeches can be interpreted as (historical) proof for the continued ‘emotionality’ of the British political discourse. Due to one of my research questions being concerned with the impact that modern-day ‘populists’ have had on the ‘emotionality’ of the overall political discourse in Britain, it is worth mentioning that the employment of highly arousing emotive words in both parties’ speeches has indeed increased since 2015 (see ‘Brexit’ campaign). However, these increases do not represent, by far, the highest values in the analysed timeframe (see ).Footnote13

Figure 1 . R-plots showing the distribution of data-values in sample1 for the Labour Party’s speeches.

Figure 2 . R-plots showing the distribution of data-values in sample1 for the Conservative Party’s speeches.

Figure 3 . Distribution of the percental coverage of all speeches (1900–2019) with highly arousing emotive words (i.e. ‘sexual’, ‘frightening’, and ‘violent stimuli’ combined) from Labour & Conservative Party leaders.

The qualitative characteristics of the analysed speeches, such as the combinations of arguments, were overall what constituted the biggest rhetorical differences between the two parties, thus, indicating their unique or ‘party-typical’ argumentative traits. Despite all speeches in sample2 stemming from different politicians, each party’s speakers still shared several argumentative qualities with their peers. The most striking example of these ‘party-typical’ traits were, in Labour’s case, how their speakers commonly argued the Market and the Inspired Order closely together. This translated to them phrasing their economic plans and demands most commonly in an anecdotical fashion (e.g. infrastructural long-term investments or the subject of (un)employment combined with their personal experiences or insights gained by speaking to workers or union leaders). Conservative Party speakers, on the other hand, intermixed their main talking points commonly with (loosely) connected arguments of the Domestic Order (e.g. Britain, duty, loyalty, hierarchies, history, family). Their (main) arguments therefore were usually not directly connected, but rather associated with nationalistic, traditional, and historical subjects and objects of worth.

Another important qualitative characteristic of the two parties can be found in their speakers’ argument formations (sample2; ). Even though both parties overwhelmingly argued their claims in a positive/regular fashion, they also employed a noteworthy amount of negative/inverted argument formations to down-value certain debated subjects or objects in their speeches (Conservative Party, averaged at about 20 per cent / per speech; Labour Party, at about 24 per cent). However, the amount of negative/inverted argument formations in Conservative Party speeches has continuously increased beyond their average since 1980. Labour Party speeches have also seen an overall increase in negative/inverted argument formations since 1980 beyond their average, except for their speech from 2000 (the only time in sample2 that Labour was the governing party). Yet throughout the analysed timeframe they exhibited more deviations from their average than Conservative Party speeches. Except for their speech from 2000 (less than Conservatives) and their speech from 1900 (equal to Conservatives), Labour Party speakers have always employed more negative/inverted argument formations in direct comparison to their Conservative counterparts.

Figure 4 . Argument formations found in the speeches from sample 2 of Labour & Conservative Party speakers.

Nevertheless, the overall increase in negative/inverted argument formations since the 1980s might suggest a general shift in both parties’ argumentative strategiesFootnote14 (i.e. adopting these increasingly negative argumentations), they might, however, also be indicators of the speakers’ position as being either the leader of the governing party (i.e. higher amounts of positive/regular argument formations, because arguments are formulated in defence of the status quo or the ‘calm state’; cf. Boltanski, Citation2012, p. 94) or being the leader of the opposition (i.e. higher amounts of negative/inverted argument formations, because the status quo is being criticized). Given the fact that this development can be observed for both parties simultaneously, it seems more likely, that a general shift in argumentative strategies has occurred. Both parties’ speakers thus have been increasingly down-valuing subjects and objects in their speeches, opting for an overall more ‘negative’ argumentation since the 1980s.

Both parties’ speakers additionally employed both types of affective quantifiers (i.e. highly arousing emotive words and sentiments) in combination with their main arguments, as well as their ‘argumentative compromises’ (cf. Boltanski & Thévenot, Citation2006, pp. 278–281). However, sentiments appeared unambiguously more often in connection with ‘argumentative compromises’. This could indicate a subconscious tendency or even an active strategy of British politicians (across party lines) to ‘emotionalize’ argumentations, which could be seen as less convincing or ‘weak’ due to their (logical) instability caused by the combination of a multiplicity of orders of worth and suggestive actions. It could also be an attempt to create the opposite effect and use the ‘emotionalization’ to down-value a ‘weak argument’ even further (e.g. when referencing the argumentation of their opponents). Prima facie, it seems that affective quantifiers – and of those particularly the sentiments – were used as enhancers of ‘weak arguments’, both positively and negatively (cf. Boltanski & Thévenot, Citation2006, pp. 278–281). An additional curious characteristic of the British political discourse is the speakers’ awareness of the act of disputing and negotiating. Party leaders of the Labour Party referenced disputes and/or the fact they were engaging in a verbal conflict more regularly (n = 17) than those of the Conservative Party (n = 6) (see sample2).

Discussion – has modern-day ‘Populism’ caused an emotionalization of the british political discourse?

To answer the question regarding the influence of modern-day ‘populism’, first the subject itself should be briefly discussed: In the ongoing (academic) debate of modern-day ‘populism’ uncertainties regarding its definitions prevail. As Moffit and Tormey (Citation2014) insist, there are ‘at least four central approaches to populism – as ideology, logic, discourse and strategy/organization – […]’ (Moffitt & Tormey, Citation2014: 383). Ungureanu and Popartan (Citation2020) further see these approaches marked by a ‘formal-substantive dichotomy’ that are characterized by often ‘overstretching’ their subject-matter and yet still having severe blind-spots, such as, for instance, overlooking ‘the centrality of antagonistic political emotions […], namely its [populism’s] anti-ideological component.’ (cf. Ungureanu & Popartan, Citation2020, p. 37). Henceforth, they suggest to instead ‘look beyond the formal–substantive dichotomy and consider the dominant [modern-day] populism as a specific type of political narrative.

Key to this perspective is not primarily ontology or ideology, but narrative patterns, political myth making and a constitutive ‘logic’ of affective intensification [via ‘antagonistic emotions’].’ (cf. Ungureanu & Popartan, Citation2020, p. 39; 42). Ungureanu and Popartan understand ‘populism’ to be ‘based on simple and accessible narrative figures that are emotionally overloaded’, typically taking a ‘Manichean political form’, in which ‘political emotions have a primordial role’ (cf. Ungureanu & Popartan, Citation2020, pp. 41–42). This understanding certainly lends itself to the neopragmatist discourse analysis conducted within this study, however, no preferences shall be given to either of the definitions introduced. What ‘populism’ truly is, does not in fact matter too much for this discussion. However, what does matter is the fact that most, if not all, approaches insist on emotion being a central aspect of ‘populist’ speech.

To thus answer the question on the influence that alleged modern-day ‘populist’ politicians have had on the emotionality of the overall political discourse in Britain, the question must be further differentiated into three sub-questions: (1) was the British political discourse ever free of emotion, and therefore free of affective quantifiers, before alleged modern-day ‘populists’ entered the discourse? (2) has the employment of affective quantifiers – and therefore the ‘emotionality’ of political speeches – drastically increased since alleged modern-day ‘populists’ entered the political stage? And (3) does modern-day ‘populism’ in Britain have a unique emotional quality that it could have introduced into the overall political discourse?

Additionally, we would need to agree upon the time that alleged modern-day ‘populists’ became a more prominent feature on the (mainstream) political stage in the UK and who, if any, of the analysed speakers of the two parties in my samples can be considered ‘populist’. According to Pappas (Citation2016), the most recent ‘wave’ of ‘populism’-research suggests that Western democracies had already been overwhelmed by a ‘populist Zeitgeist’ by the early 1990s (cf. Pappas, Citation2016, p. 5). Yet, the most recent height of ‘populist’ activities in Britain is most-often ascribed to the time leading up to the British referendum on European Union membership (‘Brexit’) and the respective campaigns, beginning in the mid-2010s (cf. De Vries, Citation2016; Lewis et al., Citation2019-1/Citation2019-2; Pappas, Citation2016; indicated by dotted-grey-line in ). The politicians in my samples, that some might classify as modern-day ‘populists’ or at the very least are alleged as displaying ‘populist’ traits, are Boris Johnson, Theresa May (Conservative) and Jeremy Corbyn (Labour) (cf. Clarke, Citation2020; Lewis et al., Citation2019-1/Citation2019-2; Schwarz, Citation2019, pp. 15–23). Without agreeing to this classification, these three shall for the purpose of my analysis, be used to examine potentially shared qualities regarding the emotionality of their speeches.

To answer the three questions: affective quantifiers appear in all analysed speeches from 1900 to 2019 of both, the Conservative Party and the Labour Party alike (see ), with only miniscule differences in the parties’ speakers’ quantitative employment of them. There was not one speech in the sample without these types of quantifiers. My findings would therefore suggest that, using the example of party leaders’ speeches from the Labour and Conservative Party, (1) British political discourse has never been free of emotion (when defined as the here chosen affective quantifiers) and that alleged modern-day ‘populists’ such as Johnson, May, and Corbyn, in fact, did not introduce them into the overall discourse. Emotionality therefore is clearly proven to be a common characteristic of British political speech and not a unique ‘populist’ trait.

Furthermore, the distribution of both types of analysed affective quantifiers appeared to be relatively volatile, undergoing continuous distributive shifts throughout the analysed timeframe.Footnote15 In the mid-2010s, yet another distinct distributive shift can be observed for both parties (with minor deviations in its onset; Labour before Conservatives). I detected for both parties’ alleged ‘populist’ speakers, a growth in their speeches’ percental coverage of highly arousing emotive words and negative sentiments, as well as a decline in the percental coverage of their speeches with positive sentiments, beginning in the mid-2010s and lasting for at least three years. Therefore, (2) an increase in affective quantifiers, since modern-day ‘populists’ entered the mainstream political discourse in the mid-2010s, is only true for highly arousing emotive words and negative sentiments. However, when evaluating this development in the context of the past century, by no means can these increases – and hence the speeches’ ‘emotionality’– be considered ‘drastic’.Footnote16 Other instances in the analysed timeframe show distinctively steeper increases, such as for example in the pre- and mid-war periods of the 1930s or 1940s (see ).

Therefore, using the aforementioned shift in the distribution of affective quantifiers as an indicator, (3) alleged modern-day ‘populists’ may have opted for a specific emotional rhetoric that incorporates increasing numbers of highly arousing emotive words and negative sentiments, while decreasing their use of positive sentiments, clearly setting themselves apart from their colleagues’ employment of affective quantifiers in 2012 and 2014 (Labour) or in 2016 (Conservative) for example (cf. ).

Yet, this constellation of affective quantifiers cannot be considered ‘unique’ to them, as it can be identified in three other periods in the analysed timeframe: 1930–1938, 1962–1968, 1996–2002. Despite having more diffuse starting and ending points, these other historical periods also exhibit this exact distributive pattern of affective quantifiers, which necessarily would make it specific (yet not unique!) to these periods of the British political discourse. Given historians’ assessments of these periods, we know that they were defined by tumultuous societal changes, (civil) pushes for modernization, political scandal and ‘polarizing political tactics’ (cf. Black Citation2017; Fisher & Fisher, Citation2009; Maslin, Citation2007). Black (Citation2017) even reported that certain central political figures in these historical timeframes were considered to be ‘populists’, either by their constituents or the media. The here identified pattern of affective quantifiers therefore is not a ‘novel’ constellation, but instead, a potentially characteristic emotional quality exhibited in politicians’ rhetoric during tumultuous political times, including but not limited to alleged ‘populists’ (cf. Black Citation2017: 132; 139; 175).

Given that the other three historical periods were longer than the period identified as that of alleged ‘modern-day populism’ (2015–2019), it could be further assumed that the current period displaying this specific emotional quality is most likely still progressing and that the ‘emotionality’ is therefore still going to increase further for a couple more years before it will drop yet again.

Conclusions: the emotionality of the British political discourse and the role of ‘Populism’

As has been demonstrated in this paper, emotion has been a volatile, yet continuous component of the argumentation of British party leaders over the past century, with positive sentiments showing the only consistent up-ward monotonic trend in the sample and across party lines. Measured via the analysis of two types of affective quantifiers, I discovered emotive words within all types of arguments, but predominantly in connection with ‘weaker’ arguments consisting of a multitude of orders of worth and suggestive actions. This emotional ‘enhancement’ of ‘weak’ arguments was employed by all speakers throughout the entire timeframe, Labour or Conservative, alleged ‘populist’ or not. Primarily, sentiments appeared within these types of arguments.

Furthermore, all the parties’ speakers share several emotional rhetorical characteristics: one being the increase in their employment of negative/inverted argument formations since the 1980s (‘down-valuing’ argumentation); another being the increase of positive sentiments since 1900. Furthermore, of the highly arousing emotive words, both parties’ speakers mainly employed a combination of violent and frightening stimuli within their speeches, usually leaning more towards violent stimuli (Conservatives more so than Labour). Labour’s most distinct argumentative feature was the persistent personalization of their economic talking points, whereas Conservatives most notably enlivened a majority of their argumentations with subjects and objects of ‘locality’ and ‘tradition’. Overall, it was the qualitative differences of the analysed speeches that allowed me to establish each party’s distinct argumentative patterns and determine that emotion played a central, yet multi-faceted role within them.

By using these findings, I have been able to contextualize and comment on the political speechmaking of politicians alleged to be (modern-day) ‘populists’ and their influence on the overall political discourse in Britain. I found that their speeches are characterized by increasing numbers of highly arousing emotive words, negative sentiments, and decreasing numbers of positive sentiments. This ‘emotional convention’ is shared with other politicians from three separate politically tumultuous periods in the overall timeframe. If one wishes to use the ‘populist’ label to describe modern-day politicians employing this specific type of emotional convention, one could claim that they were the ones who have ‘re-introduced’ it back into the British political discourse. Given the length of the three bygone periods, my results would further suggest that the ‘emotionality’ of the political discourse in today’s Britain is still likely to increase for a couple more years.

Additionally, I have been able to confirm most ‘populist’ identifiers from a previous study on U.S. politics, by testing the speeches of those politicians in sample2 alleged to be ‘populists’ (i.e. Corbyn and Johnson). Both speakers display a relatively clear argumentative strategy, high numbers of negative argument formations (highest values (Labour) and second highest values (Conservative) in sample2), mainly employed violent stimuli, and in fact made some ‘non-debatable’ claims. However, both alleged ‘populist’ speakers employed more positive than negative sentiments and not the other way around.

In conclusion, solely registering the (quantitative) appearance of affective quantifiers in political speech and basing assumptions on that, has been proven yet again, to be an unreliable method to evaluate the alleged emotional and/or ‘populist’ quality of politicians’ rhetoric, since the results for both parties only showed miniscule differences (meaning the ‘populist’ label could be extended to a multitude of politicians normally not considered to be ‘populist’, such as for example, Theresa May).

The historical context of the speeches and the development over time does in fact matter. Moving forward, I would therefore like to advise scholars researching the ‘emotionality’ of modern-day political speech – and in particular when wishing to employ the label of (modern-day) ‘populism’ – to acknowledge the complex position that emotion holds within the argumentation of (British) politicians. It should be clear by now that one is best advised to employ qualitative investigations supplemented with additional quantitative methods, as they promise more significant and meaningful results. Contextualizing affects through analysing the argumentative structures and argument formations in which they are embedded, precisely locating them within said structures/formations, looking for specific patterns and developmental trends, seems to be a more propitious approach to grasping the functional role of affective quantifiers, and thus emotion, within political discourse.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1 Acknowledgments: I would like to dedicate this paper to the late Dr Judi Atkins, who so kindly agreed to become the secondary supervisor for my cumulative PhD project before her untimely passing. As one of the authors of the (online) archive British Political Speech, her work provided the main source-material for this paper. I would also like to extend my sincerest gratitude to Professor Alan Finlayson, the primary author of said archive, for agreeing to take over Judi’s role as my secondary supervisor. His critical commentary, as well as the most generous insights he allowed me into the academic study of British Politics and Rhetoric while I visited the University of East Anglia, are of the highest value to me. Furthermore, I would like to thank my dear colleagues at the Robert K. Merton Centre for Science Studies (Berlin) for their distinct feedback and critiques, in particular: Dr Jens Ambrasat, Dr Tim Flink, Dr Stephan Gauch, and Dr Cornelia Schendzielorz. Lastly, I would like to express my gratitude towards Professor Martin Reinhart, for his continued support, his insightful commentary and general guidance throughout the writing process of this paper.

2 Additionally, ‘rhetoric’ in this study is to be defined as ‘everything a rhetor does communicatively with the aim of securing others adherence to a position: […]’. (cf. Kock & Villadsen, Citation2022, p. 6).

3 When drawing on Boltanski’s own argumentation on the matter, the actions summarized in the remaining three action regimes follow their own inner logic (or rationale), each of which only allow one order for the execution of actions, hence resulting in ‘only three kinds of situations’: situations of violence, altruism or rightness (‘contingency’). Consequentially, any executed or planned actions that can be ascribed to these remaining regimes will naturally have been executed in the logic or ‘order’ of its regime (cf. Bogusz, Citation2010, p. 58).

4 Within the PSC it is assumed that actors’ interactions can be assessed as part of one of four action regimes (i.e., the regime of violence, the regime of love or Agapé [altruism], the regime of routine or rightness, the regime of public justification, which in addition knows eight orders of worth or ‘cités’) (cf. Lemieux, Citation2014, pp. 157–158). The basic research design for a PSC analysis is described in the work ‘On Justification’ by Boltanski and Thévenot (Citation2006). Further explications and extensions were introduced in ‘Love and Justice as Competences’ (Boltanski, Citation2012), ‘On Critique’ (Boltanski, Citation2011), ‘The New Spirit of Capitalism’ (Boltanski & Chiapello, Citation2018), ‘The Sociology of Critical Capacity’ (Boltanski, Citation1996-1), ‘Endless Disputes. From Intimate Injuries to Public Denunciations’ (Boltanski, Citation1996-2 ), ‘Forms of Valuing Nature: Arguments and Modes of Justification in French and American Environmental Disputes’ (Thévenot et al., Citation2000), as well as in ‘The Moral Idealism of Ordinary People as a Sociological Challenge’ (Lemieux, Citation2014) and in Boltanski’s ‘Mysteries and Conspiracies’ (Boltanski, Citation2014). Instead of fixating on specific descriptions of (verbal) exchanges (classical discourse analysis), or dominant motives within a specific political discourse (frame-analysis) the PSC pursues a broader approach, shifting its analytical focus towards identifying general (philosophical) motives within the (every-day) argumentation of actors – their justification strategies or orders of worth –, which are knowingly as well as unknowingly called upon by the actors in situations of dispute (cf. Boltanski, Citation2012, pp. 36–43; Lemieux, Citation2014, p. 154; 157; 159-162; Thévenot et al., Citation2000: 14).

5 Emotions are generally understood as ‘evaluative [neurological] processes of different types’ and are commonly investigated by exposing test subjects to certain emotional stimuli, such as for example emotive words (cf. Jarymowicz, Citation2012, p. 9).

6 Additionally, the planned dictionary analyses are accompanied by a manual neopragmatist discourse analysis, which allows to spot and eliminate those words in the smaller sample that have changed their meanings and appear in completely inappropriate contexts.

7 Jarymowicz (Citation2012) and Jarymowicz and Imbir (Citation2015) suggested an ‘emotion duality model’, in which emotion formation is analysed under the aspect of automatic vs. controlled mechanisms, thus distinguishing the stimuli according to the response, i.e., the emotions they evoke (cf. Jarymowicz, Citation2012, p. 2). Since I am not looking at the perception level of the speeches but am merely trying to determine if emotional stimuli can be detected in the speeches of (British) politicians at all, this approach does not seem suitable for my study and consequentially will not be adapted. It does however support my claim, that the words from my dictionary of highly arousing emotive words belonging to the three categories of either ‘sex’, ‘fear’, or ‘violence’ are functioning as some sort of ‘emotional highlighters’, since these verbal stimuli tend to be mainly processed via the amygdala, and according to Jarymowicz and Imbir (Citation2015) ‘elicit automatic affective reactions and direct behavioural responses ‘bypassing the will.’’ (cf. Jarymowicz & Imbir, Citation2015, p. 184).

8 The following weights were assigned: 50 = negative/inverted; 100 = positive/regular logic according to the following rules: 50 = ‘it is/was bad/of no worth, because it is not that logic’; ‘it is/was good/of worth, because it is not that logic’; ‘negative objects from order of worth’ 100 = ‘it is/was good, because it is that logic’; ‘it is/was bad, because it is not that logic’; ‘positive objects of order of worth’

9 The speeches from sample2 were manually screened for falsely auto-coded words, which were then deleted; this changed the overall count of affective quantifiers appearing in all sampled speeches (sample1) as following: screened Codes: Pos S = 18,267 vs. non-screened Dict. Count: Pos S = 18,800 [Difference = +533 words (2.92 per cent)] screened Codes: Neg S = 14,229 vs. non-screened Dict Count: Neg S = 14,259 [Difference = +30 words (0.21 per cent)] screened Codes: Sex = 199 vs. non-screened Dict Count: Sex = 252 [Difference = +53 words (26.63 per cent)] screened Codes: Fear = 1182 vs. non-screened Dict Count: Fear = 1260 [Difference = +78 words (6.59 per cent)] screened Codes: Violence = 3173 vs. non-screened Dict Count: Violence = 3154 [Difference = -19 words (0.59 per cent)]

10 This similarity between Labour and Conservative speakers could be explained with the fact that both parties co-exist in the same political sphere (i.e., UK) and thus speak on similar topics or even react to one another and thus refer to each other’s arguments. However, this circumstance does not necessarily amount to a similar employment and combination of these argumentative motives. Labour and Conservatives might have discussed the same topics, but they have differed severely in how they argued them.

11 These numbers are equitable to a difference of 1,038 counted sentiments between Labour = 15,819 and Conservative = 16,848; compared to a total of 32,658 counted sentiments.

12 Since none of the data points in the distributions of the quantifiers appeared to be outliers (which the Mann Kendall test is sensitive to), further testing (such as the Theil-Sen estimator) to comment on the significance of the detected trend was deemed unnecessary (cf. Wilcox, Citation2004, p. 208). The test results of my Mann-Kendall computation were significant.

13 Most importantly, while both quantifiers appeared throughout all speeches, sometimes overlapping with one another, they seem to have served different distinct purposes within the arguments (e.g., supporting/de-valuing main arguments, argumentative compromises): e.g., violent stimuli (automatic coding) appeared almost exclusively within arguments from the Logic/Threat of Violence (manual coding), which confirms the validity of my dictionary of highly arousing emotive words (see Bartscherer, Citation2021).

14 Considering Tetens’ (Citation2010) remarks, I distinguish an argument into being made up of multiple statements or claims, which are each individually argued according to the rationales of either an order of worth or a suggestive action (see Tetens, Citation2010, p. 217). In that respect: (1) An argumentative strategy would describe the combination of a minimum of one orders of worth and suggestive actions that was actively employed by an actor to argue or justify a claim (usually within one document/altercation). (2) An argumentative pattern describes in which way these strategies have been combined (usually within one type of communicative medium or the totality of a discourse). (2) is the product of (1) and is passively constructed.

15 A distributive shift is to be understood as the turning-point from which (emotional) quantifiers stop increasing and begin to decrease, or vice versa.

16 Excerpt for Theresa May’s overtly ‘positive’ speech from 2016. Her speech marks the highest counted percental coverage of a Conservative Party leader’s speech with positive sentiments throughout the entire sample.

References

- Arroyas Langa, E., Fernández Ilundain, V. (2019). The politics of authenticity in populist discourse. Rhetorical analysis of a parliamentary speech by Podemos. In E. Hidalgo Tenorio, M.-A. Benitez-Castro & F. De Cesare (Eds.), Populist discourse. critical approaches to contemporary politics (pp. 17–32). Routledge.

- Baird, A., Wilson, S., Bladin, P., Saling, M., & Reutens, D. (2004). The amygdala and secual drive. Insights from temporal lobe epilepsy surgery. Annals of Neurology. An Official Journal of the American Neurological Association and the Child Neurology Society, 55(1), 87–96. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.10997

- Bartscherer, S. F. (2021). Instrumentalization of emotion during the 2016 U.S. presidential election. A neopragmatist analysis of the presidential nominees’ media communication. In Helfritzsch & M. Hipper (Eds.), Die Emotionalisierung des Politischen (pp. 319–370). Transcript Verlag.

- Bateson, G., Jackson, D. D., Haley, J., & Weakland, J. (1956). Toward a theory of schizophrenia. Behavioural Science, 1(no. 4), 251–264. https://doi.org/10.1002/bs.3830010402

- Bestgen, Y., & Vincze, N. (2012). Checking and bootstrapping lexical norms by means of word similarity indexes. Behaviour Research Methods, 44(4), 998–1006. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-012-0195-z

- Black, J. (2017). A history of Britain. 1945 to Brexit. Indiana University Press. ProQuest Ebook Central. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/huberlin-ebooks/detail.action?docID=5041706

- Bogusz, T. (2010). Zur Aktualität von Luc Boltanski. Einleitung in sein Werk. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften / Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden GmbH.

- Boltanksi, L., & Chiapello, È. (2018). Der neue Geist des Kapitalismus (pp. 152–162). Halem Verlagsgesellschaft mbH and Co. KG.

- Boltanski, L. (1996-1). The Sociology of Critical Capacity. Working Paper 96-1. In: Networks and Interpretation, Department of Sociology, Cornell University..

- Boltanski, L. (1996-2). Endless Disputes. From Intimate Injuries to Public Denunciations. Working Paper 96-2. In: Networks and Interpretation, Department of Sociology, Cornell University.

- Boltanski, L. (2011). On critique. A sociology of emancipation. Polity Press.

- Boltanski, L. (2012). Love and justice as competences. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Boltanski, L. (2014). Mysteries and conspiracies. Detective stories, spy novels and the making of modern societies’. Polity Press.

- Boltanski, L., & Thévenot, L. (1999). The Sociology of Critical capacity. European Journal of Social Theory, 2(3), 359–377. https://doi.org/10.1177/136843199002003010

- Boltanski, L., & Thévenot, L. (2006). In C. Porter (Translated by), On justification. Economies of worth. Princeton University Press. First published in 1991.

- Bonikowski, B., & Gidron, N. (2016). The populist style in American politics: Presidential campaign discourse, 1952–1996. Social Forces, 94(4), 1593–1621. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sov120

- Bos, L., Schemer, C., Corbu, N., Hameleers, M., Andreadis, I. S., Anne Schmuck, D., Reinemann, C., & Fawzi, N. (2020). The effects of populism as a social identity frame on persuasion and mobilisation: evidence from a 15-country experiment. European Journal of Political Research, 59(1), 3–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12334

- Bradley, M. M., & Lang, P. J. (1999). ‘Affective norms for English words (ANEW): instruction manual and affective ratings’. Technical report C-1, The center for research in psychophysiology. University of Florida.

- Browning, C. S. (2019). Brexit populism and fantasies of fulfilment. Cambridge Review of International Affairs, 32(3), 222–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/09557571.2019.1567461

- Carretié, L. (December 2014). Exogenous (automatic) attention to emotional stimuli: A review.’ cognitive. Affective, & Behavioural Neuroscience, 14(no. 4), 1228–1258. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13415-014-0270-2

- Clark, D. L. (ed.). (2010). The Brain and behaviour. An introduction to behavioural neuroanatomy’. Third edition. Cambridge University Press.

- Clarke, J. (2020). Building the ‘boris’ bloc: Angry politics in turbulent times. Soundings, 74(74), 118–135. https://doi.org/10.3898/SOUN.74.08.2020

- Creamer, E. G., & Ghoston, M. (2013). Using a mixed methods content analysis to analyse mission statements from colleges of engineering. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 7(2), 110–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689812458976

- De Blasio, E., & Sorice, M. (2019). The Rise of populist parties in Italy. Techno-populism between neo-liberalism and direct democracy. In E. Hidalgo Tenorio, M.-A. Benitez-Castro, & F. De Cesare (Eds.), Populist Discourse: Critical Approaches to Contemporary politics (pp. 33–50). Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group.

- De Vries, C. (2016). ‘Populism on the Rise?’ https://www.ox.ac.uk/news-and-events/oxford-and-brexit/brexit-analysis/populism-rise (May 18, 2021).

- Finlayson, A., & Martin, J. (2008). ‘It Ain’t What You Say … ’: British political Studies and the analysis of speech and rhetoric. British Politics, 3(4), 445–464. https://doi.org/10.1057/bp.2008.21

- Finlayson, A., & Martin, J. (2014). Introduction. In J. Atkins, A. Finlayson, J. Martin, & K. Phillips (Eds.), Rhetoric in British Politics and society (pp. 1–16). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Fisher, P., & Fisher, R. (2009). Tomorrow we live: Fascist visions of education in 1930s Britain. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 30, 71–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425690802514466

- Freeman, S., & Ingbretsen, H. (August 2014). Amygdala responsivity to high-level Social information from unseen faces. In: Journal of Neuroscience 6, 34(32), 10573–10581. Society for Neuroscience. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5063-13.2014

- Gárdos-Orosz, F., & Szente, Z.2021). Populist challenges to constitutional interpretation in Europe and beyond. 1st ed. Routledge. 2021. Series: Comparative constitutional change: Routledge. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/9781000386202 (July 27, 2021).

- George, J. M. (2016). Affect, emotion, and decision making. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 136, 47–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2016.06.004

- Hamann, S. (2005). Sex differences in the responses of the human amygdala. In: Neuroscientist 2005, 11(4): Neuroscience Update. Department of Psychology, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia: 288–293.

- Hamann, S., Herman, R. A., Nolan, C. L., & Wallen, K. (2004 Mar). Men and women differ in amygdala response to visual sexual stimuli. Nature Neuroscience, 7(4), 411–416. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn1208

- Hidalgo Tenorio, E., Benitez-Castro, M.-A., & De Cesare, F. (eds.). (2019). Populist discourse: Critical approaches to contemporary politics. Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group.

- Hirsch, R. M., Slack, J. R., & Smith, R. A. (Feb 1982). Techniques of trend analysis for monthly water quality data. Water Resources Research, 18(No.1), 107–121. https://doi.org/10.1029/WR018i001p00107

- Hu, M., & Liu, B. (2004). ‘Mining and summarizing customer reviews. Proceedings of the ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge, Discovery and Data Mining (KDD-2004).’, Aug 22–25, 2004, Seattle, Washington, USA.

- Imbir, K. K., Jurkiewicz, G., Duda-Goławska, J., & Żygierewicz, J. (2019). The role of valence and origin of emotions in emotional categorization task for words. Journal of Neurolinguistics, 52, 100854. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneuroling.2019.100854

- Jarymowicz, M. (May 2012). Understanding Human emotions: On the different bases of pleasure and pain. Journal of Russian & East European Psychology, 50(no. 3), 9–25. https://doi.org/10.2753/RPO1061-0405500301

- Jarymowicz, M. T., & Imbir, K. K. (April 2015). Toward a human emotions taxonomy (based on their automatic vs. reflective origin). Emotion Review, 7(no. 2), 183–188. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073914555923

- Kenny, P. D. (2018). Populism in southeast asia. Elements in politics and society in southeast asia. Cambridge University Press.

- Kensinger, E. A. (2007). Negative emotion enhances memory accuracy: Behavioural and neuroimaging evidence. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16(4), 213–218. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00506.x

- Kock, C., & Villadsen, L. (2022). Populist rhetorics. Case studies and a minimalist definition. Rhetoric and society series. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kousta, S.-T., Vigliocco, G., Vinson, D. P., Andrews, M., & Del Campo, E. (2011). The representation of abstract words: Why emotion matters. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 140(no. 1), 14–34. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021446

- Kuckartz, U. (2014). Mixed methods. Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden.

- Laclau, E. (2005). Populism: What's in a name?. In F. Panizza (Ed.), Populism and the mirror of democracy (pp. 32–49). Verso.

- Lemieux, C. (2014). The moral idealism of ordinary people as a sociological challenge: Reflections on the French reception of Luc Boltanski and laurent thévenot's On justification. In S. Susen, & B. S. Turner (Eds.), The spirit of Luc Boltanski. Essays on the ‘Pragmatic Sociology of Critique’ (pp. 153–170). Anthem Press.

- Lewis, P., Barr, C., & Clarke, S. (2019-1). ‘How we combed leaders’ speeches to gauge populist rise.’ The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/mar/06/how-we-combed-leaders-speeches-to-gauge-populist-rise (May 27, 2021).

- Lewis, P., Barr, C., Clarke, S., Voce, A., Levett, C., & Gutiérrez, P. (2019-2). ‘Revealed: The Rise and Rise of Populist Rhetoric.’ The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/ng-interactive/2019/mar/06/revealed-the-rise-and-rise-of-populist-rhetoric (May 18, 2021).

- Lowndes, J. (2015). From founding violence to political hegemony: The Conservative populism of George wallace. In F. Panizza (Ed.), 2005. Populism and the Mirror of democracy (pp. 144–171). Verso.

- Maslin, J. (2007). ‘Brokaw Explores Another Turning Point, the ‘60s.’ The New York Times, November 5. (May 25, 2021).

- Miczek, K. A. (Ed.). (1994). Neurochemistry and pharmacotherapeutic management of Aggression and violence’. In Understanding and preventing violence, Vol.2 behavioural influences (pp. 245–514). National Academy of Sciences.

- Miczek, K. A. (October 31 2007). Neurobiology of escalated Aggression and violence. Journal of Neuroscience, 27(44), 11803–11806. Society for Neuroscience. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3500-07.2007

- Moffitt, B., & Tormey, S. (2014). Rethinking populism: Politics, mediatisation and political style. Political Studies, 62, 381–397. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9248.12032

- Molyneux, M. (2017). Populism: A deflationary view. Economy and Society, 46, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085147.2017.1308059

- Moore, S., & Oaksford, M. (2002). Emotional cognition. From Brain to behaviour. John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Panizza, F. (2005). Populism and the Mirror of democracy. Verso.

- Pappas, T. S. (2016). Modern populism: Research advances, conceptual and methodological pitfalls, and the Minimal definition. In T. S. Pappas (Ed.), Oxford research encyclopaedia of politics (pp. 1–24). Oxford University Press.

- Phelps, E. A., & Whalen, P. J. (2009). The Human amygdala. The Guilford Press.

- Phillips, L. H., Slessor, G., Baily, P. E., & Henry, J. D. (2014). Older adults’ perception of Social and emotional cues. Oxford University Press. (from Oxford Handbooks online).

- Reisberg, D., & Hertel, P. (eds.). (2004). Memory and emotion, series in affective science. Oxford University Press.

- Salmela, M., & von Scheve, C. (2018). Emotional dynamics of right- and left-wing political populism. Humanity & Society, 42(4), 434–454. https://doi.org/10.1177/0160597618802521

- Schultebraucks, K., Deuter, C. E., Duesenberg, M., Schulze, L., Hellmann-Regen, J., Domke, A., Lockenvitz, L., Kuehl, L. K., Otte, C., & Wingenfeld, K. (2016). Selective attention to emotional cues and emotion recognition in healthy subjects: The role of mineralocorticoid receptor stimulation. Psychopharmacology, 233(18), 3405–3415. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-016-4380-0

- Schwarz, B. (2019). Boris johnson's conservatism: An insurrection against political reason? Soundings, 73(73), 12–23. https://doi.org/10.3898/SOUN.73.02.2019

- Sennwald, V., Pool, E., Brosch, T., Delplanque, B.-D., Francesco, S., & Sander, D. (2015). Emotional Attention for Erotic Stimuli: Cognitive and Brain mechanisms: Emotional Attention for Erotic stimuli. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 524(no. 8), 1668–1675. https://doi.org/10.1002/cne.23859

- Stevenson, R. A., Mikels, J. A., & James, T. W. (Nov 2007). Characterization of the affective norms for English words by discrete emotional categories. Behaviour Research Methods, 39(no.4), 1020–1024. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03192999

- Sturm, Hermann, M. (ed.). (2009). Lehrbuch der klinischen neuropsychologie. Grundlagen, methoden, diagnostik, therapie’. 2. Auflg (pp. 44–63). Spektrum, Akad. Verl.

- Tetens, H. (2010). Philosophisches argumentieren. Eine einführung.‘ 3., unveränderte auflage. Verlag C.H. Beck oHG.

- Thévenot, L., Moody, M., & Lafaye, C. (2000). Forms of valuing nature: Arguments and modes of justification in french and american environmental disputes. In M. Lamont & L. Thévenot (Eds.), Rethinking Comparative Cultural Sociology. Repertoires of Evaluation in France and the United States (pp. 229–272). Cambridge University Press.

- Tyng, C. M., Amin, H. U., Saad, M. N. M., & Malik, A. S. (August 24, 2017). The Influences of emotion on learning and memory. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01454

- Ungureanu, C., & Popartan, A. (2020). Populism as narrative, myth making, and the ‘logic’ of politic emotions. Journal of the British Academy, 8s1, 37–43. https://doi.org/10.5871/jba/008s1.037

- Victor, E. C., Sansosti, A. A., Bowman, H. C., & Hariri, A. R. (2015). Differential patterns of Amygdala and ventral striatum activation predict gender-specific changes in sexual risk behaviour. Journal of Neuroscience, 35(23), 8896–8900. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0737-15.2015

- Vuilleumier, P. (December 2005). How brains beware: Neural Mechanisms of emotional attention. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 9(no. 12), 585–594. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2005.10.011

- Warriner, A. B., Kuperman, V., & Brysbaert, M. (December 2013). Norms of valence, arousal, and dominance for 13,915 English lemmas. Behaviour Research Methods, 45(4), 1191–1207. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-012-0314-x

- Watts, J., & Bale, T. (2018). Populism as an intra-Party phenomenon: The British Labour Party under Jeremy corbyn. British Journal of Politics & International Relations, 21(1), 99–115. https://doi.org/10.1177/1369148118806115

- Whiteley, P., Larsen, E., Goodwin, M., & Clarke, H. (2019). Party activism in the populist radical right: The case of the UK Independence Party. Party Politics: 1354068819880142, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068819880142

- Wilcox, R. R. (2004). Some results on extensions and modifications of the theil — Sen regression estimator. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 57(2), 265–280. https://doi.org/10.1348/0007110042307230

- Zheng, W.-L., Zhu, J.-Y., & Lu, B.-L. (2017). Identifying stable patterns over time for emotion recognition from EEG. IEEE Transactions on Affective Computing, 10(no. 3), 417–429. doi:10.1109/TAFFC.2017.2712143