ABSTRACT

This paper explores the experiences and interpretations of non-communicable diseases in two secondary Ugandan cities: Mbale and Mbarara. Drawing inspiration from the concepts of social determinants of health, and geographic scholarship on embedded gendered and classed power dynamics, I employ a qualitative exploration and thick description to analyse data from twenty-two in-depth biographic interviews. Interviewees were from a range of circumstances, including, as AbdouMaliq Simone described, ‘the missing people’. Findings detail aspects of life with diabetes, obesity or hypertension in these cities, noting some views of wider social determinants, and some possible barriers to effective non-communicable disease management. Analysis of interpretations around gendered difference in obesity, in particular, revealed provocative conceptualisations of gendered livelihood strategies interwoven with body size beliefs, and the realities of oft-times insecure daily urban lives. The paper makes apparent the value of incorporating qualitative study, together with quantitative assessments, to investigate the experiences and interpretations of non-communicable disease in a specific context. In addition, the work provides insight into barriers to healthy urban living in the current socio-economic context of Ugandan, and potentially other sub-Saharan African, cities.

Experiences and interpretations of non-communicable diseases in urban Uganda

Introduction and rationale

Smaller cities of sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) have been understudied (Thornton Citation2008, Satterthwaite Citation2017), though there is a recent and growing body of work focusing on this city scale (see for example Battersby and Watson (Citation2019) or Riley et al. (Citation2018)). Research in such contexts is important since it is not certain that smaller cities will simply follow their bigger siblings. Smaller, or secondary, cities also may experience different land and livelihood circumstances, and morphological conditions, than larger, denser cities (Dodman et al. Citation2017, Mackay Citation2018). In addition, more of the SSA population resides in small-to-medium cities, and such urban environments are the areas anticipated to experience the largest future growth (Dodman et al. Citation2017). The cities of Mbale and Mbarara were purposively selected as two secondary cities of Uganda. They are not intended to be statistically representative of all Ugandan secondary cities, though they do share much in common with many of Uganda’s small and growing towns. They are located roughly 400 km from the capital, Kampala, in opposite directions. Mbale lies in the Mt. Elgon area to the north-east, towards the border with Kenya. Mbarara is a regional administrative centre to the south-west. Although relatively small in size, both towns are facing rapid growth (>3% p.a. (Habitat Citation2011, Citation2012) with some estimating Mbarara to be experiencing growth rates >8% p.a. (UN-HABITAT Citation2016). Mbale municipality (which includes surrounding villages) had an official population of 92,863 residents in 2016, and Mbarara municipality had 195,160 residents (UBoS Citation2016). Population statistics are not gathered at the level below municipality (see Mackay et al. (Citation2018) and Mackay (Citation2019b, Citation2019c)) for further description of these cities). Of significance is that both Mbale and Mbarara have been selected by Uganda’s new urban development plan to be two of four regional growth cities (NPA Citation2017). There is a need, therefore, to focus attention on how this envisaged urban growth and change can be managed in a healthy and sustainable way. Indeed, as Satterthwaite notes in his call for greater attention to be paid to small cities in SSA as they struggle with communicable and non-communicable disease challenges and a double burden of malnutrition (over- and under-nutrition): ‘most cities in the region have almost no investment capacity as most of their limited revenues go on recurrent expenditures’ (Satterthwaite Citation2017, p. 18).

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), non-communicable diseases (NCDs) (obesity, diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, cancer) are the major causes of death globally, responsible for 70% of global mortality (WHO Citation2017). A recent report by a collaboration of East African Science Academies (UNAS) suggests that the prevalence of NCDs in Africa is expected to rise by 27% in coming decades, (UNAS Citation2018). The UNAS report notes that behavioural aspects play a role, but they emphasise a growing recognition that environmental factors, socio-economic circumstances (such as gender, class, education), and stressful living conditions are key contributors to NCD burden (UNAS Citation2018). UNAS notes a class dimension, describing how: ‘Low income populations are primarily affected by poor environmental conditions and poor nutrient access, while high-income populations are primarily affected by unhealthy diets and sedentary lifestyles’ (UNAS Citation2018, p. 32). Yet they also emphasise that ‘across all income groups less nutritious foods are being consumed’ (UNAS Citation2018, pp. 27, my emphasis). Much of the research on nutrition transitions in SSA, changed urban food environments, urban lifestyles and NCDs (Popkin Citation2001, Citation2015, Popkin et al. Citation2012, Steyn and Mchiza Citation2014, Haggblade et al. Citation2016), however, has focused on national aggregate data or on the large and capital cities (Thornton Citation2008, Himmelgreen et al. Citation2014, Nichols Citation2017). It is not certain that smaller cities face the same circumstances. This paper contributes to reducing knowledge gaps on NCDs in smaller, but rapidly growing, cities in SSA.

Uganda could attribute 35% of total deaths to NCDs in 2016, according to the WHO (Citation2017). It is thought that a Ugandan ran a 22% risk of meeting a premature death due to NCDS (WHO Citation2017). Accurate measures of prevalence levels are challenged by limitations on diagnostics and by poor health-seeking behaviours (Whyte Citation2016). The high level of undiagnosed cases is of concern, with estimates that 50% of diabetes cases go undiagnosed in East Africa (UNAS Citation2018). A recent nationally representative survey of 3987 Ugandans found a 24% raised blood pressure prevalence (higher in men than in women), with 76% of these being unaware and not on treatment (STEPS Citation2014). The survey revealed a prevalence of 3.3% raised blood glucose including diabetes (STEPS Citation2014). Of these, 89% had not been aware of their status, and were not taking treatment (ibid). The report found association between urban residence and high blood pressure, diabetes, raised cholesterol and obesity (STEPS Citation2014). Across the STEPS sample, the prevalence of overweight was 14.5% and obesity 4.6% (ibid). Obesity was higher in females than in males (7.5% compared with 1.6%), and more prevalent in urban than in rural areas (STEPS Citation2014). My own project’s 2015 survey in Mbale and Mbarara found higher levels of overweight and obesityFootnote1 than the STEPS report (Mackay et al. Citation2018). This random systematic survey (of every third household) covered 1025 households across Mbale and 970 households across Mbarara. As well as weighing and measuring willing adults, we asked whether anyone within the household had been diagnosed with diabetes, hypertension or heart problems. Specific details on this survey (considered representative of households across each city, but not taken to be representative of other Ugandan cities), are published in Mackay et al. (Citation2018). Significant for this paper is the body mass index (BMI) data, it’s gendered nature, and the self-reported experience of other NCDs within households. To summarise: overweight prevalence in Mbarara was 29% in females, 27% in males, and obesity prevalence was 27% in females compared to 11% in males (Mackay et al. Citation2018). The pattern was similar in Mbale, with 30% female overweight compared to 20% in males. Female obesity prevalence in Mbale was 18% compared to just 7% obesity in males (Mackay et al. Citation2018). Regarding diabetes, 8% of surveyed Mbarara households and 12% surveyed Mbale households reported having someone in the household diagnosed with diabetes (ibid). For hypertension, the figures were 11% Mbarara and 22% Mbale households (ibid). Considering heart-related problems, 6% Mbarara and 11% Mbale households claimed to have a member suffering from such (Mackay et al. Citation2018). Note: these figures do not equate to standard measures of prevalence: they are self-reported and household level, thus there could be more than one sufferer per household.

In this paper, I present an in-depth follow-up investigation of these NCD data. The statistics above are the reason why I wanted to explore further, using in-depth interviews, the experiences of a variety of men and women with different circumstances in life. What did they experience and interpret regarding overweight, obesity and other NCDs, and differential gendered expression of these? This is the research question this paper addresses. I was interested, in addition, to consider how findings would relate to feminist geographic conceptualisations of emplaced gendered and classed power relations (Gilbert Citation1997, McDowell Citation1999, Bondi and Rose Citation2003, Marston and Doshi Citation2016, Parker Citation2016), and to the concept of the social determinants of health (SDH) (Marmot Citation2005, Marmot et al. Citation2008). Qualitative exploration of localised perceptions and interpretations of NCDs are necessary in order to design effective responses. Measurable/countable data, statistical analyses, randomised control trials show part of the story (Parker Citation2016, Winchester and Rofe Citation2016). Yet when we are dealing with societal understandings we need to investigate our very human explanations of phenomena (Parker Citation2016). If we don’t, our policy or practice recommendations run the risk of being, at best, misaligned (Setel Citation2003), at worst, failing due to missing very specific and contextual ‘causes of the causes’ (CSDH Citation2008, p. 42).

In the remainder of the paper, I first outline the theoretical frames of references: social determinants of health (SDH), and the tradition of critical interpretivism (Lincoln et al. Citation2011) within feminist geography. I then describe the methodology before presenting my findings from qualitative content analysis. I conclude with the reflection that, in the context of these two secondary Ugandan cities, residents already have considerable awareness and experience of NCDs, and of the parameters for a balanced diet and healthy lifestyle. Yet, much as Hunter-Adams (Citation2018) found in South Africa, I find subtle, sometimes contradictory, discourses influencing interpretations of NCDs, particularly of obesity. Findings suggest a finesse in overlooking the female reproductive roleFootnote2 and the influence of embedded power dynamics, as well as noting the crucial contribution of poverty/insecurity. The paper underlines the value in incorporating qualitative study to assess health in the city and to design interventions. The work points towards some shortcomings of planning in urban Africa to support healthy cities and equitable access to healthy diets and exercise opportunity.

Theory frames

Studies that have investigated NCDs within the SSA context have tended to work within a discourse of individual behaviours, attitudes and body-size perceptions and tended to assert blame, as both Hunter-Adams (Citation2018) and Warin (Citation2015) contend. Many have advocated for awareness-raising and behavioural change as a management strategy (see Hunter-Adams (Citation2018) for an overview and Reubi et al.’s (Citation2016) review of the political response to NCDs in the Global South). Yet more recent literature has found that awareness of healthy diets, healthy lifestyles and risks associated with NCDs (obesity in particular), is evident within SSA communities (Sedibe et al. Citation2014, Hunter-Adams Citation2018, Mackay Citation2019b). The ability to act to influence diets and daily life–the degree of agency an individual has in reality–has received less recognition as being a hindrance to NCD prevention (Hunter-Adams Citation2018, Mackay Citation2019b). In addition, less attention has been paid to the importance of ‘past and present hunger’ (Hunter-Adams Citation2018, p. 357), of developmental origins (Barker Citation1997), and of possible resistance to a framing of ‘wrong’ or out-of-place bodies (Reubi et al. Citation2016) in debates on NCDs. As Setel argued already in 2003: ‘In the African context, key conceptual questions must be asked about the social and cultural determinants, management, meaning, and impact of emerging NCDs’ (Setel Citation2003, p. 150).

This work explores such ideas and interpretations of fatness and fitness (more broadly health), and the finesse with which discourses of bodies and behaviours, of localised power dynamics, in relation to NCDs (and particularly obesity) influence interpretations in urban Uganda. Finesse as a verb can mean to: ‘[s]lyly attempt to avoid blame or censure when dealing with (a situation or problem)’ (Lexico Citation2019). The initial postulation of all respondents when considering causes of rising NCDs in Mbale and Mbarara was always behavioural, tending to deflect responsibility by blaming women (see (Warin Citation2015) and Mackay (Citation2019a, Citation2019b)). Yet my research reveals diverse influences on local interpretations of NCDs that go beyond behavioural choices to include wider social determinants of health (SDH).

In 2005 Michael Marmot wrote about the WHO’s decision to establish an investigative commission on the SDHs (Marmot Citation2005). He noted that differences in disease prevalence and life expectancy within and between populations were not founded in biology but rather in societal inclusion or exclusion, and in social, economic and political policies influencing resource allocations (ibid). Marmot cites Geoffrey Rose’s concept of the ‘causes of the causes’ of health inequalities, going on to describe ten key factors (or social determinants) of health inequality, albeit from a European perspective. These included the social gradient (or social location), stress, early life, social exclusion, work, unemployment, social support, addiction, food, transport (Marmot Citation2005). Societal, psychological, political and structural factors are as relevant as material deprivations in shaping health environments (Marmot et al. Citation2008). Equity and social justice are crucial in ensuring all groups have the same opportunity for health (Braveman and Gruskin Citation2003). While not claiming to be an exhaustive analysis of the SDHs in these Ugandan cities, my work sheds light on local perceptions of these. In particular, my findings explore some of the interpretations of obese, hypertensive or diabetic bodies in Mbale and Mbarara. Ideas regarding the SDHs go beyond claims of obesogenic urban environments (fast foods, eating out, processed foods, and more sedentary lifestyles), and concerns of a nutrition transition towards a so-called ‘Western pattern’ diet (Popkin Citation2001, Citation2015, Pingali Citation2007, Popkin et al. Citation2012, Steyn and Mchiza Citation2014, Haggblade et al. Citation2016). Instead of looking at what is present within the environment, an SDH and qualitative feminist geographic approach digs deeper and considers what is accessed, and how foods and environments are utilised, by individuals and groups in their daily lives.

Geographers with an interest in social justice have made important contributions to both urban studies and to health science and food environments literature. Their contributions have helped uncover and deconstruct how various dimensions of difference (be they gender, class, race, ethnicity, religion, ability) interact with ‘other structures or relations of inequality in shaping urban processes and daily life in cities’ (Gilbert Citation1997, p. 166). A series of reviews elaborate on these contributions, see for example Marston and Doshi (Citation2016), Parker (Citation2016), Bondi and Rose (Citation2003), and Gilbert (Citation1997). Much of this work has demonstrated the value in qualitative analyses of lived experiences, while maintaining consciousness of relations with wider societal structures (Parker Citation2016). An important contribution of this research is the affirmation of the role of place and ‘lived geographies’ (Bondi and Rose Citation2003, p. 232). Places, identities, interpretations, discourses are closely interlinked. Scholars in this tradition have analysed how differentiated identities and experiences (e.g. gendered, classed, disabled, diseased, obese) are constructed in specific places. They also note how these spaces, and access to the resources within them, actively shape identities and experiences (Gilbert Citation1997, Bondi and Rose Citation2003).

These theory frames, feminist geography and the social determinants of health, emphasise why, and how, analyses of health experiences and interpretations can make an important contribution towards efforts to create healthy urban environments for all. My analysis of how some Ugandans within small cities interpreted the causes of, and influences upon, NCDs follows in the vein of these scholars’ work.

Methodology

Data collection: As noted in the introduction, I designed this qualitative research to explore further the findings from a 2015 household survey conducted in Mbale and Mbarara (Mackay et al. Citation2018). Specifically, these were the fairly high prevalence of obesity, with females significantly more affected than males, and a fairly common self-reported experience of NCDs. Ethical approval for the study was granted by the Uganda National Council of Science and Technology, and by the Regional Ethical Review Board, Umeå, Sweden. I conducted the twenty-two in-depth thematic biographic interviews upon which I base this paper, during February-May 2017. I felt interviews to be appropriate as I wished to explore the topic of NCDs from the perspective of the daily-lived experiences and interpretations of a diverse range of people. Thus, my interview sampling was purposive for a range of gender, class and livelihood circumstances. Sampling is not designed to be representative of any specific group but rather to strive towards breadth of experience, reflecting Simone’s concern with the missing people (Simone Citation2014). By this term, Simone was noting that a broad range straddling the ‘middle classes’ but including the upper poor, the working class and the lower middle-class, are often omitted from research–to the detriment of our understanding of urban livelihoods in SSA (Simone Citation2014). However, although interview sampling was purposive there was a link to the earlier survey. Due to that data being georeferenced, I was able to work with a geographic information system (GIS) to analyse spatial patterns in the data. The survey investigated the food environments using the internationally validated tools of the household food insecurity access prevalence (HFIAP), the Household Dietary Diversity Score (HDDS), and a measure of poverty known as the lived poverty index (LPI).Footnote3 In addition, we gathered detailed information on incomes, farming activity, food transfers, and BMI data. There is insufficient space to describe these variables further–a detailed description has been published in Mackay et al. (Citation2018). Relevant is that having this georeferenced data allowed a hotspot analysis of inequalities in these variables. A hotspot analysis presents cartographically households that had average scores (in a variable), and households with scores that were statistically significantly different from randomly clustered (either higher- or lower- than average, i.e. hotspots or coldspots).Footnote4 This provided insight into the situation in different parts of the cities. The hotspot analysis highlighted city areas that were generally more food secure, areas that were less food secure, neighbourhoods with concentrations of higher weight adults, for example, and neighbourhoods that did not fit any pattern (areas I termed anomaly areas), across multiple of my variables. To inform my purposive sampling for the interviews, I drew a selection grid (approximately 200 m × 200 m) in the GIS, highlighting approximately 20 households in a neighbourhood of interest. I chose at least one neighbourhood in each city where there were clusters of households whose food and livelihood circumstances were good for the city context, one neighbourhood where households were generally not scoring well across a number of these variables, and an average or an anomaly area. Therefore, although my sampling is principally purposive and intended for thick description, it may be possible to make some generalisation to the immediate neighbourhood.

With households selected in the GIS, I then identified the specific households searching firstly for respondents who had indicated that they would be happy to be contacted again. I selected broadly to balance gender, age, BMI data, household structure (single parent or multiple-adult) and household food situation. Who was ultimately interviewed, depended on whether we were able to get in touch with them by phone or physical follow-up, the individual’s preferences and availability, and whether they still lived in the city. If someone declined to be interviewed, I went to the next person on my list. Participation was voluntary with verbal informed consent given. Seventeen of the interviews were selected in this way. In addition, a further five interviewees (three men and two women) were purposively added during fieldwork to broaden the diversity. Four of these were food secure salaried professionals, and one was an informally employed youth living with his parents. Thus, I conducted twenty-two interviews in total: ten in Mbale (eight women, two men) and twelve in Mbarara (six women, six men). These interviewees held a range of employment, livelihood and food security positions ranging from food secure and salaried urban elite to students, to stay-at-home housewives, to the self-employed, informally employed or unemployed. More detailed description of interviewees is available in Mackay (Citation2019b).

The number of interviews was restricted by time and resource limitations, but was also influenced by the concept of ‘saturation’, where it is felt that further interviews do not reveal much new information, similar themes/explanations recur (Hay Citation2016). The time and place for interview was usually pre-arranged by telephone, mostly occurring in the person’s home or workplace. I led sixteen of the interviews in English, and my field assistant led six in Luganda. Interviews were audio recorded (with permission) for later transcription into English. All names are pseudonyms. I structured the interviews around themes of daily urban life, diets and health. Interview duration varied between 35–70 minutes, with most taking one hour.

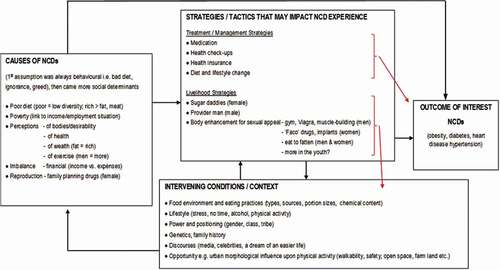

Data analysis: I worked with the interview transcripts in Atlas.ti software sorting thematically first (food, farming, health, urban life). I then applied an iterative and abductive content coding (Locke et al. Citation2015) of the health and urban life data. Here, I used Anselm Straus’ advice to consider causal claims within the data, representations of strategies or tactics, intervening conditions/contextual factors, and outcomes (experience/description) of the phenomenon of interest (NCDs) (Cope Citation2016). From this process of sorting and analysis I created a concept map (Cope Citation2016) of the experiences and interpretations of NCDs. During the concept mapping process I further analysed the data, identifying themes within the perceptions of causes, and the strategies/tactics. I focus this paper around these themes (Cope Citation2016). This approach is a method of thick description (Holliday Citation2016), framed by discursive commentary (Holliday Citation2016). A discursive commentary, common within ethnography, consists of an interaction of data, with analysis, and with literature (Holliday Citation2016).

In the remainder of the paper, I describe some local experiences of NCDs (of family histories and life with NCDs) to provide insight into the context. I structure the following discursive commentary around the themes identified from interviewees’ perceptions of the wider causes (social determinants) of NCDs, and of the livelihoods strategies/tactics they felt may be influencing NCDs (here interviewees focused on obesity, likely due to its visibility), see :

Table 1. Themes framing the discursive commentary

Findings and discussion

The result of the concept mapping is shown in . This depicts the initial assumption of behavioural causes of NCDs, but also reveals a good awareness of a number of SDHs, in terms of body perceptions, and of the female reproductive role. SDHs that were felt to contribute to the causes of NCDs included poverty, financial imbalance, calorific imbalance, employment situation and environmental pollutants (see ). The treatment and management strategies raised were what might be expected: diet and lifestyle change, medication, health check-ups, health insurance ().

Figure 1. Concept map of interviewee interpretations of non-communicable diseases in two Ugandan towns.

Some local experiences – family histories and life with non-communicable diseases

I found a good level of awareness of, and direct and indirect experiences with, NCDs (diabetes known locally as ‘blood sugar’, hypertension simply called ‘pressure’), and of the risks associated with excess weight. shows these experiences, where nine individuals were themselves overweight or obese according to WHO classifications (WHO Citation2006), two of whom also lived with diabetes, and three were also hypertensive (direct experience). Eleven out of the twenty-two interviewees also had indirect experience of NCDs via a spouse or close relation living with at least one NCD ().

Table 2. Interviewee direct and indirect experiences of non-communicable diseases

Awareness of NCDs did not seem to differ by social positioning (gender, class, education level). Rania (an obese, married, mother and full-time professional) and Innocent (an obese, hypertensive, health professional)Footnote5 in particular talked about their personal understandings and familial experience, pointing to hereditary components that researchers have highlighted (Barker Citation1997, Hughes Citation2014, Warin Citation2015). Rania cheerfully acknowledges that:

Am fat! And my weight is actually what?, it’s a lot eh?! And you know, am beyond that body mass index thing! … Am considered even obese! But medically they have tested my pressure – they always find it normal; my sugar levels, everything is always okay! (Rania, Mbale).

She went on to describe how almost all her siblings were overweight, and two of her sisters were diabetic and hypertensive, and she mused about the influence of genetics. Erik, one of the young male students, also spoke of genetic susceptibility to obesity and diabetes. When I asked Innocent whether there was a family history, her response was concerning:

Yes. The diabetes. There is a lot of it! Actually, my mother died because of diabetes. I have lost a sister and a brother. But those living, we are four now with diabetes! (Innocent, Mbarara)

She noted that the medications were many and expensive and that it could be a challenge to follow the recommended diet due to costs and a busy lifestyle. When I enquired whether, from both her personal and professional experience, she felt that NCDs were on the increase she affirmed noting:

when I was doing those courses in the 90s you didn’t hear of those diseases a lot. When you would hear of a patient who has diabetes you would run to see how this patient is presenting. But these days, in school, you are not surprised … sometimes I go to the main hospital to attend the diabetes clinic–we are very many (Innocent, Mbarara).

Innocent also felt that diabetes was indiscriminate:

It is everyone! Mmm. Everyone! The poor … when I go to the main hospital [referring to the specialist diabetes clinic] you see the poor, the middle class, the rich, the smaller size, the big size like me. We are mixed up! (Innocent, Mbarara)

Some described a cost-sensitive and pragmatic management strategy, such as Eydie (a mother and part-time farmer), who noted she only took a tablet for hypertension when she felt she needed it and she used the cheapest variety. Nailah, a married mother and part-time clothes seller, made an association between being overweight and getting other NCDs (as did Jaspar):

because myself, I was skinny. I was very okay, doing my work well. But, when I added on weight, and grew fat, I got diseases … Blood sugar, ulcers and other diseases (Nailah, Mbale)

This section shows that awareness and experience of NCDs is already quite apparent within these secondary city communities, across a range of positioned people and their families. NCD burden is not just a large-city phenomenon. Awareness of the risks associated with carrying too much weight were also fairly known. The arguments of some strands of research, briefly described in section 1, about ignorance as a contributor to NCDs, and awareness raising as a solution, thus do not resonate strongly with my findings. In the remainder of the paper, I further explore the SDHs that interviewees had identified under ‘Causes’ in . I then focus on the claims of specific livelihood strategies () that were perceived as possibly influencing NCD burden.

Some social determinants of health

Body size perceptions and connotations of power, of money, of respect

It was the students and the somewhat better off individuals, who spoke most of body-size perceptions and the connotation with power, prestige, wealth. A number of researchers have written about body size perceptions in the African context and connotations of large size with wealth/power, or of larger women being linked with attractiveness (see for example Benkeser et al. (Citation2012) or Holdsworth et al. (Citation2004)). I probed about such perceptions, though it was not uncommon that an interviewee brought up the subject of their own accord. Kristina (a retired food secure teacher in Mbale) was quick to note ‘that’s how we show our money in Africa’ as she laughed, talking about large-bodied people, especially political elites and the super-rich. Jonathan (social work graduate, self-employed food trader) described how ‘When it comes for us here, weight is symbolic of how much a person has’, meaning how much money. Yet others talked of a pride in being large, particularly for women:

Yeah there are some women who prefer those large bodies, for prestige … just to show off. Like, you know eh [laughs slightly embarrassed], when you’re fat they say ‘that’s a good lady!’ Men also prefer fat ladies. Like, in Uganda, everyone wants to have that fat big boobs and everything, so they eat more of foods which bring out the body (Isabelle, student, Mbale)

Solomon and Jaspar, however, as two educated, salaried, food secure urban elite, noted that some still think this way but that times were changing and health awareness was better:

Yeah, it used to be in the past, but even today … As much as, eh, people are now more exposed [meaning health awareness has improved] compared to past times, but there are those that, when they see somebody fat they say ‘ah those ones have got money! (Solomon, Mbarara)

The three young male students in Ian’s interviewFootnote6 were vocal, humorous and frustrated with how common they felt it was that they were judged by their body sizes, which in their cases were slim:

when a woman sees a tiny man [meaning slim], you try to tap her [chat her up, befriend her], she might not give you a hearing; but when a man of a good mass [gestures for bulk with his arms], tries her, she will respond! (Adam, student, Mbarara)

Of course, in the Ugandan context the experience of HIV/AIDS has left imprints that filter into present-day perceptions where people still associate slim bodies with being ill, as Whyte (Citation2016) also notes for Uganda, and Hunter-Adams (Citation2018) for South Africa. In line with feminist geographic theorising, this is an example of how specific place-based histories and narratives shape ideas and interpretations, how the past influences the present (McDowell Citation1999, Massey Citation1991, Williams-Forson and Wilkerson Citation2011).

Finally, in relation to body size perceptions, the issue of tribe arose, though mentioned only by men:

You can find, like there are different tribes. Now like me, am a Mukiga, and some of these ah Muhima [these are different tribes] – for them … you find they are all fat. But mostly the Bahima women are always fat (Erik, student, Mbarara)

‘Because they take a lot of milk’ added Ian and Adam together (students, Mbarara)

Jaspar also noted ‘we have tribes where women are fatter’. I discuss this association of particular tribes with particular food environments further in section 4.2.3. The points of importance for this section, has been to show some local discourses of how large body size may be linked to conceptualisations of power, of money, of respect; as well as to tribal affiliation or female reproductive capacity. Such socio-spatial interpretations (McDowell Citation1999) are necessary to engage with, and possibly even work with in new and creative ways, in any effort to try to reduce vulnerability to NCDs. This is also a clear example of some context-specific socio-psychological and emplaced SDHs that Marmot (Citation2005) described.

Family planning drugs – a claimed cause of female obesity

What I wish to draw attention to in this section is the claimed role of family planning in creating gendered difference in overweight and obesity. Men raised this almost as often as women did. Out of 22 interviews, five women and four men suggested that family planning drugs were contributing to higher female obesity. Solomon notes:

yeah I think, for women, even the family planning methods that they use also, I think it is contributing a lot … so they become obese (Solomon, married, full-time professional, Mbarara)

and Pricilla and Nailah reflect:

women … because of family planning. The things they use is the cause of overweight (Pricilla, married, shop owner, Mbarara)

Eeeeh … you can find a person who didn’t have weight, but when she goes for family planning … and she gets weight. But it’s not based on eating (Nailah, married, clothes seller, Mbale)

In terms of which contraceptive women were taking, at least two interviewees talked of ‘Injectaplan’. This is a hormonal muscle injection, taken by the woman every 13 weeks, which has been increasing in popularity in Uganda, with weight-gain a known side effect (Stanback et al. Citation2011, Ouma et al. Citation2015).

This finding of the claim that family-planning drugs contribute to female obesity goes somewhat against a discourse on sub-Saharan African reproductive health–that of disempowered women unable to exert influence on their fertility rates or contraceptive use, see for example Kibira et al. (Citation2014) and Lesch and Kruger (Citation2004). In terms of implications for NCD-reduction attempts, framed by understandings of the SDHs (Marmot Citation2005, Marmot et al. Citation2008) and of intra-household power geometries (McDowell Citation1999, Massey Citation2004), there may not be an easy answer here. Working to reduce weight-gain side effects of family planning interventions may be one way forward.

A mixed view on obesogenic urban environments

Obesogenic food and drink environments were felt to be less relevant for the majority, filtered as such were by access and affordability

I did not find strong evidence of claims for obesogenic urban food environments (in the form of fast foods, eating out, processed foods) creating a crisis of NCDs. All interviewees mainly consuming maize/beans, matooke (cooking bananas)/beans, rice/beans diets, and most ate only twice a day, with one-meal-per-day being quite common (see Mackay Citation2019b) for detailed findings on interviewees’ diets and food sources). A number of my interviewees (and other parts of my own research (Mackay et al. Citation2018, Mackay Citation2019b)) were sceptical, particularly of the claimed role of processed foods and eating out from the nutrition transition model (Popkin Citation1994, Citation2001, Popkin et al. Citation2012). Innocent was extremely sceptical when asked whether she thought food products and cooking patterns were changing, especially if women were working more outside of the home:

I don’t think it is so much happening here, to buy processed food. Because, first of all, processed food is expensive. Most people, they buy the local foods and prepare … So it might have interfered with their eating habits [for women working outside the home], by maybe taking one meal a day, or eating very little, which they can afford. But eating the processed food, I don’t think it so much happens (Innocent, Mbarara)

A young female student was puzzled by gendered differences in weight gain because as she saw it, everyone largely consumed the same meal and the same products and she asked ‘why women having so much weight than men, yet we eat the same food?’ (Lalita, student, Mbarara).

Innocent’s and Lalita’s comments point much more to access and affordability as critical factors in daily urban life and move us again away from behavioural literatures towards social determinants, and to poverty and inequality as contributors to differential NCDs expression. Indeed my findings support the concerns of Hunter-Adams that:

The discourse of improving the accuracy of self-perceived weight, of dispelling cultural myths or taking responsibility for diet, assume that target populations have a low level of dietary knowledge juxtaposed with a high level of choice and control over multiple factors related to obesity and diet-related noncommunicable disease (Hunter-Adams Citation2018, pp. 348–349)

The factor that may fit with claims of obesogenic urban environments, and possibly with changing gender roles, was the claimed role of alcohol. This was presented, by all who mentioned it, as a male activity and a cause of male obesity:

And another thing what makes a shape of someone? … this alcohol, our local beer this … now you see, this man who takes beer – they are always big (Erik, student, Mbarara)

Janet also blamed alcohol for her husband’s death from obesity and heart failure:

Yes, cos he used to take a lot of beer. He used to put weight so that’s why he developed cardiac arrest (Janet, seamstress working from home, Mbale)

The tribal connotation with large women, described earlier, was related to cattle rearing and milk drinking by Ian and his friends. This milk connotation was raised by others, including well-educated professional with a cattle-rearing tradition of his own, Jaspar. When I enquired why women may be more affected by obesity, men possibly more by hypertension or heart disease, he analysed thus:

Maybe they have appetite. They also have time … Because men usually, they transact so much, they move a lot. A man, maybe he is driving a taxi, do you think that man ever gets time for himself? All the time he is on the road looking for money. But the women is at home. Eating her food. Eating g-nuts.Footnote7 Drinking milk. You know? I think that’s one of the reasons (Jaspar, Mbarara)

Jaspar’s interpretations here cut across a number of themes in this paper, about claimed gendered difference in eating behaviours, behavioural factors (greed, over-consumption), about time-use and physical activity levels. He also believed men were more stressed than women (because of their role as ‘provider’), thus less able to gain weight and providing a reason (in his analysis) for elevated blood pressure to be more common in men. Yet my data does not provide support for claims that women ate more, were less stressed nor more greedy/ignorant. In addition, studies of milk consumption usually proclaim the nutritional benefits of milk, see for example a review by Pereira (Citation2014).

In my opinion, there is an important implication here for combating NCDs, in urban or rural communities in Uganda. This would be, firstly, to investigate in more detail how widespread this association of milk with weight gain actually is. Second, would be to work to combat this conceptualisation of milk in the popular imaginary, along with its inherent association to place, occupation, tribe and gender, in line with critical interpretive scholars’ approaches (Williams-Forson and Wilkerson Citation2011, Hovorka Citation2012), and understandings of the SDH (Marmot Citation2005).

I wonder whether what these men may rather be seeing in their equation of ‘obese women-milk-cattle-tribe’ may rather be a link to wealth and power (McDowell Citation1999) generated by cattle-production and influencing changed diet and lifestyle circumstances. Further investigation would be necessary. As I have written elsewhere tribe, or ethnicity, has ‘geospatial, cultural, nostalgic and identity connotations, and food is one way of expressing this’ (Mackay Citation2019b, p. 5). Yet this local connection of milk with obesity and NCD risk is concerning and suggests there may be need for promoting the benefits of milk consumption within a balanced diet.

In recognising these social determinants, whereby an urban environment might both limit food access and limit individual agency,Footnote8 we bring a responsibility for diets and health firmly within the remit of urban planning. Food access is constrained via both the urban food system itself (food sources, specific products, food prices, access to land to farm) but also via the urban livelihood context and the often informal and variable incomes and circumstances that residents must navigate in cities of Uganda. This is the message of Battersby, Watson and colleagues, who advocate for a food lens as a useful starting point from which to trace ‘the complex connections between formal and informal sectors and the role of the state and other stakeholders in shaping urban conditions’ (Battersby and Watson Citation2019, p. 7). Such a mapping, of the interacting conditions and actors influencing urban diets and health, could indicate where urban planning interventions could reduce inequalities in diets and health and thus help reduce the future burden of NCDs.

My findings do not suggest strongly gendered difference in eating patterns nor food products (with the possible exception of alcohol). Neither are my findings particularly supportive of claims that the eating of processed foods or frequent eating out are causes of growing NCD burden (Popkin Citation2001), particularly for the ‘missing people’ (Simone Citation2014). Rather, the findings in this paper are more supportive of claims that wider social and environmental determinants of health (Marmot Citation2005, Marmot et al. Citation2008) are important contributors to rising NCD burden within urban Africa. Research highlighting biologically differing mechanisms in how male and female bodies process fats, on how early-childhood metabolic changes can predispose to later-life obesity (possibly more pronounced in females) (Barker Citation1997, Warin Citation2015), or the role of environmental toxins (Guthman Citation2012), or starch quality and processing level (Mattei et al. Citation2015), are relevant and may provide entry-points for urban planning interventions. The remainder of this paper considers some socio-psychological determinants of health that interviewees felt may contribute to how NCDs were interpreted in Mbale and Mbarara.

Obesogenic physical/exercise environments – some support for concerns with urban sedentary living, and possible gendered difference in these

Exercise and physical activity patterns and the opportunity and ability to incorporate such within an urban resident’s daily life is another dimension of possible obesogenic urban environments, alongside urban food systems. The loudest message from my interviews was that actively seeking to exercise was not widespread within these cities. Most common was walking or gardening, with some few speaking of running or jogging. Rania raises important points about how the morphology and condition of the urban environment–both the physical infrastructure of smooth and available sidewalks, or of open space leisure areas, but also the social environment of the neighbourhood (incorporating feeling safe from crime, but additionally from ridicule)–has important facilitator roles:

I have been doing a bit of exercise and that involved jogging, I would jog, walk, jog, but that was about three-weeks ago when I was still living nearby here in the centre of town where I felt secure, like to get up like at 5am or so … but now I have moved out of town … to my own place where we built our home. So … we are not so used to the environment there to be confident that you can get up, and get out of the compound and do your exercise. And then of course the road is not paved like it was here … you can get scared to injure yourself (Rania, Mbale)

Rania described how urban planners need to design for exercise spaces and safe, walkable streets, but she also touches upon points of cultural acceptability, of shyness and of confidence–issues particularly relevant for women:

… provide some open spaces where people can go and exercise for instance, some playgrounds for children … Sometimes it’s about space you know … Because somebody may want to exercise but they fear to … yah, they fear that eh, to run in the street: what will people say eh? But if it’s a specialised place for that kind of thing, then people will get confidence

From the stay-at-home working mother perspective, Janet cited her occasional gardening, for food for the family, as her main exercise opportunity, and the two young female students I interviewed played volleyball or swam. Innocent and Rania both noted some of the challenges facing women to engage in exercise within a city. These can be summarised as time challenges, motivational challenges, and challenges related to the road and pavement infrastructure, to the physical space to run or walk, to the cost of gyms, and to safety concerns:

Ah, most women, the type of exercise they do is walking. But ah the type of walking they do, some of us, is not the one which is accepted. You walk at your pace. But … you are supposed to walk at a high speed and start sweating (Innocent, Mbarara)

A number of the men interviewed claimed women did very little exercise. Yet their own exercise consisted mainly of walking. My data do suggest that men may walk more than women. In particular, younger men and the informally employed, or unemployed men, were walking kilometres a day round the city in search of jobs or business. Ian, a young student, also hinted at a local perception that only the poor walk: ‘They say we are too mean, too economical’. Rasmus, an Mbarara elder in his 60s, said he liked to run. He also noted that his position of leadership within the community set an example and had acted as a motivator for others to join him in running.

The findings in this section, along with the work of others in the critical tradition, remind us of how various aspects of identity (including gender, ethnicity, class) can interact in specific geographic locations in specific embodied ways to influence experience and understandings of health and disease (Bondi and Rose Citation2003, Mollett and Faria Citation2018). As researchers interested in good food and health environments in specific cities, we need to engage with such localised discourses, imaginaries and interpretations, as much as with diagnostic and health infrastructures, and with local planner visions of the city and urban life (Kiggundu Citation2014, Parnell and Pieterse Citation2014, UN-HABITAT Citation2016, Battersby and Watson Citation2019) in order to support healthy urban spaces.

Livelihood strategies and tactics perceived as contributors to non-communicable diseases

Rejecting propositions of a new breed of (urban) women–the idle lazy housewife–as being a reason for greater female obesity prevalence

The first assumption in response to questions as to why women in Mbale and Mbarara may be more affected by obesity than men was that they ate too much, they were idle, or they ate the wrong things (). These ideas were common in my male interviewees, but a good number of women themselves made such statements. My earlier research with local healthcare professionals revealed similar discussions (Mackay Citation2019a). In my interviews, I probed such claims by asking about women who stayed at home (so-called urban housewivesFootnote9). Innocent was dubious and indignant:

… in Uganda here there are not many women who are seated at home. Either they are working for government, or they are working for organisations, or they have gardens. But seated at home and you are waiting either for your spouse to bring food home and eat! I don’t think they are very many! … Some women, they go to the market, some go to their gardens, some go to organisations and some work like us.

… I even sit in MCH [mother and child health] where we are taking histories of anti-natal mothers … they say ‘I have business in the market’, ah ‘I’m working in the garage’, ah ‘I have a garden where I go to’ … Like, if you have 20 mothers, like 3 will tell you they are housewives. But even these housewives, they have something they are doing at home! Either they are making crochet, they are making mats, but you will fail to get one who just sits!’ (Innocent, Mbarara)

These views were supported by my interviews with stay-at-home women themselves, except perhaps for those who had infants under two-years. At this stage they were more dependent on their partners and communities while they provided early maternal care. Yet, as soon as the child is old enough most women need to do something to contribute to family survival, as Innocent so clearly describes above. Nailah was also disbelieving of claims of female laziness, greed, or specific consumption practices:

Aaah, no [she laughs]. It is not true! [she is emphatic about this]. But it [meaning a greater female weight-gain] is not based on eating (Nailah, Mbale)

Much in accord with Warin’s claim that women and mothers are often scapegoated as responsible for their own, and others’ obesity (Warin Citation2015) were these assertions of women’s complicity in obesity (see Mackay (Citation2019a)). In response to such suggestions–that women eat while they are cooking, picking the best bits, or mothers at home eat more in quantity and frequency–Innocent again was incredulous:

But we [here she is speaking collectively of Ugandans generally] are poor! You cannot have the food to cook and eat, cook and eat?! Where do you get the food?! [all laugh at this point] People are poor! … And besides, in town … you have to plan for your families, school fees, clothing, medication … etc. I don’t think there are many who cook, eat; cook, eat! [Innocent is shaking her head, clearly bemused and angered, by the suggestion of these (mostly) men]

These findings resonate with Linda McDowell’s and others’ claims of how women’s work is rendered invisible and undervalued (McDowell Citation1999). As Parker wrote, albeit in relation to a US city:

urban subjectivities, texts, and discourses … tended to valorize masculinities, whiteness and related notions of competition; efficiency and autonomy … They also devalued care, connection, femininities, social reproduction, feminism, and racialized women (Parker Citation2016, p. 1353)

My findings also link to conceptualisations of ‘provider man’ (Wyrod Citation2008, Miller et al. Citation2011, Mackay Citation2019a, Citation2019b). The claims and counter claims surrounding urban dietary and social environments suggest to me both the need for further investigations of gendered and occupationally diverse physical activity patterns and personal food environments. They also highlight an important dimension of any NCD prevention strategy: this would be to actively combat and make visible women’s work in local discourse, particularly around obesity, and to tackle head-on the quick/easy tendency to, as Warin writes, blame women and mothers (Warin Citation2015) for obesity in the population.

The remaining sections analyse the vein of data concerned sugar daddies, provider men and transactional relationships; as well as a related thread on strategies of deliberate weight-gain in order to secure a livelihood. These claims are provocative. They speak of gendered and classed relationships, of who has power and who does not, and they raise ethical questions. How real or widespread such representations are, is not possible to tell from my data. What is relevant here is that these narratives of urban bodies and behaviours exist. I should emphasise that it was mainly the students (in their twenties) who spoke in depth about these points.

Of sugar daddies, provider man, & transactional relationships as non-communicable diseases contributors

My field assistant asked a young female student we were interviewing whether she felt that many of her female compatriots were conceptualising of marriage as offering a secure livelihood strategy after graduation (probing claims from our earlier work of ‘provider man’ (AUTHOR-3)). Isabelle laughed and felt it relevant but countered with claims of the irresponsible manFootnote10:

That’s a nice question! [she laughs again] Yeah, some of us think of that – that they have men who are taking care of them so they are not struggling. But me … You know men are somehow, they shower you with love, first time, but after delivering with you two to three kids, or one kid they dump you! You go back to your mother’s place (Isabelle, student, Mbale)

Yet Isabelle rather felt it was crucial to find her own work and provide for herself noting that: ‘If you get some work and you be busy, you will not be tempted to have these sugar daddies!’ She then claimed that such a strategy (searching for a man to provide), was common, whether in a straightforward marital partnership, to extra-marital relationships, mistresses and sugar daddies. She, and a number of male students noted that women try to increase their curves (via deliberate eating of fatty or dense food, or via drugs, or implants) in order to be seen as attractive, in order to secure a ‘provider’:

Isabelle: ‘Yeah, it’s so common at campus. Every girl wants to have a man to help her

Author: Sugar daddies? Are these always much older guys or not necessarily?

Isabelle: Much older guys! Who are already married, yeah! And they take advantage of the girls, students who have small problems.

Jaspar concurs with these claims of sugar daddies, provider men and transactional relationships, also linking such to problems with again rising HIV prevalence and to other diseases, including obesity:

You find young girls who have just graduated from university. They are looking for these men who are married. Yes. Not for jobs. Ok, first of all for jobs, if they can easily connect to them. If they can’t easily connect for them then they want to survive: get money, get rent from them, you know? And in the end sleep with them (Jaspar, Mbarara)

A number of studies from Uganda have discussed the relative commonness of having multiple partners, and embedded ideas of transactions within intimate relationships, particularly in times of poverty or livelihood insecurity (Wyrod Citation2008, Miller et al. Citation2011, Barratt et al. Citation2012). Such claims are not new. Yet how widespread or representative they are, is unclear, and my data is not suited to generalisation. The link to body size perceptions and potential for NCDs is further elucidated in the following section.

Claimed deliberate weight-gain and body manipulation as non-communicable diseases contributors

The dialogue in Box 1 presents perspectives from three young unmarried men about buying the kind of body ‘women’ would like to have, as a strategy to wealth and marriage.

At this point, the conversation turned to how men were not immune to such but that they rarely bought implants. What men did, according to them, was go to the gym and build muscles, and take muscle-building dietary supplements. Bright, a highly food and livelihood insecure single male from Mbarara, also spoke of pressures on men to be the provider, and of associations of masculinity with sexual prowess. He claimed that men were vulnerable to taking muscle-building supplements, and to taking Viagra. He also concurred with the view on deliberate body manipulation as a livelihood strategy, noting aggressive marketing from implantation, herbal remedy and food supplement companies in multiple media (FACO was the term commonly used when speaking of food supplements, or body implants etc., this is actually a company widely known for selling such in Uganda) and describing a female friend of his who got implants. When I enquired as to why his friend wanted to increase her curves, he replied that she was very happy with the result:

Don’t think these women are buying it because they wish it. They know what comes out! This woman say she is going to inject herself in the behind. She is just doing it to get more behind so that when you see her moving you say ‘aaahahe, I wish I could discover what is behind’ [meaning that men find her attractive and want to be with her]. Because once you go there, you will be now to spoon feed her! [meaning to look after her and pay for her]

Isabelle was also aware of, and concerned about, the long-term health implications of food supplements and body manipulations:

Yeah … there are those who, like, they do that just for the sake of being fat [referring to enhancing their weight]. Like those who go for those FACO products. Even if you tell a lady that ‘these things are not good’, then she’ll tell you ‘no, I don’t want to be left behind. I also need to get this’, you know. Not considering the side effect of it. (Isabelle, student, Mbale)

Yet others, such as Nailah and Kristina, argued that deliberate weight-gain and body enhancement was rarely seen in Mbale or Mbarara. They portrayed such as more of a capital city thing, and more something that celebrities and the rich did. How much truth lies in these descriptions, and how prevalent a female strategy such may be, is not possible to assert from my data. What is relevant, however, is that these perceptions exist. They have possible implications for NCD reduction ambitions.

Is it significant that it was mainly the youth who discussed these sugar daddy/transactional relationships and strategic body manipulations? Might this be a reflection of a new generation, of campus attitudes, or of a greater interest in and exposure to a diverse array of media and news outlets? Social media channels, WhatsApp in particular, are widely used in Uganda, and the international music culture and celebrity interest (particularly from black America and South Africa) are major communicators of information/dis-information, for better or worse. How do these message about bodies, livelihoods, desirability play into the growing obesity/NCD burden in SSA? We need to better understand and engage with such ideas if we wish to combat the risks of excess weight.

How do the claimed strategies of sugar daddies, body manipulations, relate to theory? They evolve out of place-based discourses. These findings are in support of feminist geographers’ arguments of how specific places are relevant to the social determinants of health (McDowell Citation1999, Yancey et al. Citation2006). Equating body size with power or wealth, and with local conceptualisations of marriage as security, and provider man as a viable and acceptable livelihood strategy (both within, outside of and beyond marriage) arise from past traditions as well as practical need. Yet in current Ugandan urban environments of informal economies, insecure income and employment situations, of obesity despite low food security and low dietary diversity (Mackay et al. Citation2018), there is evidence that these ideas of provider man, of large size indicating a good life, are being eroded (Barratt et al. Citation2012). It may be, however, that the claimed weight-gain-as-livelihood-strategy is rather the result of the failure of modernisation and urban development (Popkin Citation2001, Citation2015, Popkin et al. Citation2012) to bring secure jobs and access to balanced diets and healthcare for all (Turok and McGranahan Citation2013). These may be strategies, though perhaps not widespread, that make sense and yield results in the absence of other options. The current level of unemployment and the lack of formal salaried employment, combined with population growth and the specific characteristics of African urbanism, are especially challenging for Ugandans, particularly the youth (Cobbinah et al. Citation2015, Ngoma and Ntale Citation2016, Dodman et al. Citation2017, Datzberger Citation2018). BBC Africa Eye recently featured a video documentary on the claimed growing sugar daddy phenomenon within Kenya, prompting considerable online debate (Kadandara Citation2018). I am not certain that I agree with the filmmaker who linked the trend to social media, a ‘celebrity’ mentality, and modern ‘vanity’ however. My feeling is that poverty, and the insecurity of daily urban African life in many SSA cities, remains an underlying motivator. This topic may deserve further investigation.

Interviewees recognised a number of local SDHs (). Small asset bases and high vulnerability ultimately underpin these SDHs (as a cause of the causes of NCDs). Some further SDHs not specifically mentioned by interviewees might include the sources of food, the quality and processing level of food products, portion sizes; time and well-being as a factor within urban lifestyle and cooking ability, as well as factors related to accessing the healthcare infrastructure. Yet the main factor that no interviewee mentioned, when considering NCDs was the role of epigenetics and metabolic influences and the importance of the first 1000 days of life (Barker Citation1997, Cusick and Georgieff Citation2019). Research has shown that the early moments in life are crucial for human development and experiencing nutritional scarcity during this time period sets in place metabolic changes that predispose an individual to obesity in later adulthood, under certain conditions (ibid). It is perhaps not surprising that interviewees did not mention such as a contributor to adult NCDs since this is relatively specialist knowledge. The complex interactive mechanisms between poverty, livelihood insecurity and material hunger (i.e. social and environmental determinants), together with biological processes, point to the importance of the socio-economic and political environment in contributing to NCDs. Urban planners could be more proactive in working for better health and nutrition in cities of SSA, if these interlinkages were more widely recognised.

Conclusions

This research has explored local experiences and interpretations of NCDs (especially of diabetes, hypertension and obesity) and possible gendered differences, in two secondary Ugandan cities. The work further investigated findings from an earlier household survey, which had revealed some cause for concern regarding NCDs. Awareness and experience of NCDs, was quite apparent across the range of Mbale and Mbarara residents interviewed. Awareness of the risks associated with too great an excess of weight were generally known. Yet people navigate multiple, sometimes conflicting, interpretations and values attributed to bodies and behaviours, just as Hunter-Adams (Citation2018) found in South Africa. Regarding the gendered expression of overweight and obesity, some interviewees defaulted quickly to the assumption that if one was overweight one must simply have been eating too much (and women specifically), or that a person lacked self-discipline. This conforms to the behavioural view discussed at the outset of this paper. This behavioural approach has tended to depict obesity and other NCDs as a result of communities not knowing which food types were bad–the problem was ignorance and the solution thus nutrition education.

I did not find support for these greed/ignorance claims, in this context of two secondary Ugandan cities. I rather found that the majority of those I spoke with were well aware of what a healthy balanced diet might look like, what a healthy urban lifestyle might entail (Mackay Citation2019b). Rather than lacking in awareness, I found people simply unable to do what they would like to do in terms of eating patterns, diet diversity and daily life due to a lack of finance, or a lack of access to such foodstuffs (Mackay Citation2019b), and due to the restrictions of the urban environment. This is supported by a body of other studies, see for example Battersby and Watson (Citation2019), Hunter-Adams (Citation2018) and Tacoli (Citation2012).

In this work I explored place-based discourses and perceptions that may be influencing interpretations of NCDs, particularly of obesity (Gilbert Citation1997, Bondi and Rose Citation2003). Findings suggest a finesse in overlooking the female reproductive role, and reveal the influence of embedded gendered and classed power dynamics (McDowell Citation1999). Findings highlight some wider social determinants of the urban food, health and infrastructural environment, such as body size perceptions and connotations of power, female contraceptive injections, or urban design. In addition, the paper reveals how local interpretations of a person’s positionality in life (both inherent identity features, and socio-economic circumstances) can influence NCD experience and understanding. Some of the claimed deliberate strategies to manipulate bodies, or to attract providers, were a way of trying to improve a person’s power and positioning within the society and urban environment they found themselves in (their social location (McDowell Citation1999, Parker Citation2016)). These perceived and claimed strategies make visible some urban Ugandan social determinants of health (Marmot et al. Citation2008).

Awareness of how unequal and unjust socio-economic and health systems, together with features of the urban built environment, work as factors contributing to NCD experience, was apparent in many of my individual interviews, and in earlier discussions with local healthcare professionals (Mackay Citation2019a). Policy or practical intervention strategies to combat growing NCD burden must investigate not only the medical/biological causes, but also the socio-cultural and environmental influences (SDHs). These SDHs work to limit the ability to implement healthy diets and healthy lifestyles, as well as influencing local discourses and interpretations of certain bodies and behaviours.

In addition this paper also reveals some of the value in incorporating qualitative study together with quantitative assessments to investigate how NCDs are experienced and interpreted in a specific context. The views and ideas put forward here, about body sizes, livelihood insecurity, transactional relationships and women’s roles, are difficult to uncover via diagnostic/quantitative survey alone, yet they are crucially relevant for planning for healthier cities in Africa. An implication is to support mixed methods investigations.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Professor and Head of Department Frank Mugagga, Department of Geography, GeoInformatics and Climatic Sciences, Makerere University, for his support and enthusiasm. You were the first point of contact with local stakeholders, as well as with potential interviewees – I am grateful for the dedication and professionalism with which you approached this task. Richard Tusabe – thank you for your engagement and encouragement, your translations and transcriptions. Your efforts helped create this manuscript. Last, but in no way least, I humbly thank all the interviewees who committed their time and shared their experiences and understandings. I hope that I have done justice to your stories. Any misinterpretations are mine alone.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Heather Mackay

Heather Mackay is a geographer working at the intersection of agriculture, food, and health in global north and south. She completed her bachelors in Geography at Aberdeen University, Scotland and holds a Masters degree in Rural Resources and Environmental Management from Imperial College London; and a Masters in Spatial Planning and Development from Umeå University, Sweden. She worked 10 years in international development for NGOs and private consulting companies in the UK, USA and Ghana before returning to academia. Her doctoral research, completed in 2019, investigated in what ways transitions at the nexus of urbanisation, food environments, and lifestyles were occurring in secondary cities of Uganda. In addition, she has worked on urban agriculture and urban food systems, as well as in the topic of migration. Heather works across a mix of methods.

Notes

1. Body mass index levels in accordance with WHO guidelines and classifications (WHO Citation2006).

2. By the female reproductive role, I mean both the literal childbearing role, but also the ongoing child-rearing role, but in addition, I mean the wider running (reproducing) of the household, supporting all its members to perform their productive activities by shopping, cleaning, clothing, cooking, encouraging, and paying education and so on. For more discussion on the common overlooking of the female reproductive role see for example Chapter 3 in (McDowell Citation1999).

3. For further information on these refer to Coates et al. (Citation2007) and Swindale and Bilinsky (Citation2006) and to (Mackay et al. Citation2018).

4. For further information on spatial hotspot cluster analysis see ESRI (Citation2019).

5. Both these individuals used the term ‘obese’ to describe themselves.

6. The interview was arranged with Ian as he had been part of the 2015 survey, but when we turned up to meet him he had brought two fellow male students (Erik and Adam) with him so we ended up with an improvised mini-focus group. However, I only include Ian in the statistics in .

7. Groundnuts.

8. The ability to make healthy food and lifestyle choices.

9. In an earlier phase of this research project it was claimed that being a housewife at home was a new feature of modern urban living because no rural women could ever afford to stay at home idle, she (the rural woman) was presented as always needing to farm, to fetch water, to fetch fuel (Mackay Citation2019a).

10. For more on this concept of provider/irresponsible man in the Ugandan context see (Mackay Citation2019a) and Wyrod (Citation2008).

References

- Barker, D.J., 1997. Maternal nutrition, fetal nutrition, and disease in later life. Nutrition, 13 (9), 807–813. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0899-9007(97)00193-7.

- Barratt, C., Mbonye, M., and Seeley, J., 2012. Between town and country: shifting identity and migrant youth in Uganda. The Journal of modern African studies, 50 (2), 201–223. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022278X1200002X.

- Battersby, J. and Watson, V., eds. 2019. Urban food systems governance and poverty in african cities open access. Oxon, UK: Routledge.

- Benkeser, R.N., Biritwum, R., and Hill, A.G., 2012. Prevalence of overweight and obesity and perception of healthy and desirable body size in Urban, Ghanaian women. Ghana medical journal, 42, 2.

- Bondi, L. and Rose, D., 2003. Constructing gender, constructing the urban: a review of Anglo-American feminist urban geography. Gender, Place & Culture, 10 (3), 229–245. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369032000114000.

- Braveman, P. and Gruskin, S., 2003. Defining equity in health. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 57 (4), 254–258. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.57.4.254.

- Coates, J., Swindale, A., and Bilinsky, P. (2007). Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) for measurement of household food access: indicator guide (v.3). Washington, DC. Available from: www.fantaproject.org

- Cobbinah, P.B., Erdiaw-Kwasie, M.O., and Amoateng, P., 2015. Africa’s urbanisation: implications for sustainable development. Cities, 47, 62–72. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2015.03.013

- Cope, M., 2016. Organizing and analyzing qualitative data. In: I. Hay, ed. Qualitative research methods in human geography. Ontaria, Canada: Oxford University Press, 373–393.

- CSDH, 2008. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Geneva, Switzerland.

- Cusick, S. and Georgieff, M. (2019). The first 1000 days of life: the brain’s window of opportunity. Available from: https://www.unicef-irc.org/article/958-the-first-1000-days-of-life-the-brains-window-of-opportunity.html.

- Datzberger, S., 2018. Why education is not helping the poor. Findings from Uganda. World development, 110, 124–139. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.05.022

- Dodman, D., et al., 2017. African Urbanisation and Urbanism: implications for risk accumulation and reduction. International journal of disaster risk reduction, 26, 7–15. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2017.06.029

- ESRI, 2019. How hot spot analysis (Getis-Ord Gi*) works. Available from: https://pro.arcgis.com/en/pro-app/tool-reference/spatial-statistics/h-how-hot-spot-analysis-getis-ord-gi-spatial-stati.htm.

- Gilbert, M.R., 1997. Feminism and difference in urban geography. Urban geography, 18 (2), 166–179. doi:https://doi.org/10.2747/0272-3638.18.2.166.

- Guthman, J., 2012. Opening up the black box of the body in geographical obesity research: toward a critical political ecology of fat. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 102 (5), 951–957. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00045608.2012.659635.

- Habitat, 2011. Mbale urban profile (978-92-1-132-446-4). Nairobi, Kenya. http://unhabitat.org/books/mbale-urban-profile-uganda/.

- Habitat, 2012. Mbarara municipality urban profile. Nairobi, Kenya. Available from: http://unhabitat.org/books/mbarara-municipality-urban-profile-uganda/.

- Haggblade, S., et al., 2016. Emerging early actions to bend the curve in Sub-Saharan Africa’s nutrition transition. Food Nutrition Bulletin, 37 (2), 219–241. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27036627.

- Hay, I., 2016. Qualitative research methods in human geography. 4th ed. Ontario, Canada: Oxford University Press.

- Himmelgreen, D.A., et al., 2014. Using a biocultural approach to examine migration/globalization, diet quality, and energy balance. Physiology, 134, 76–85.

- Holdsworth, M., et al., 2004. Perceptions of healthy and desirable body size in urban Senegalese women. International journal of obesity, 28 (12), 1561. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0802739.

- Holliday, A., 2016. Doing & writing qualitative research. London, UK: Sage Publications.

- Hovorka, A.J., 2012. Women/chickens vs. men/cattle: insights on gender–species intersectionality. Geoforum, 43 (4), 875–884. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2012.02.005.

- Hughes, V., 2014. Epigenetics: the Sins of the Father. Nature, 507 (7490), 22–24. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/507022a.

- Hunter-Adams, J., 2018. Perceptions of weight in relation to health, hunger, and belonging among women in periurban South Africa. Health care for women international, 40 (4), 341–364.

- Kadandara, N., (Writer) and News, B., (Director), 2018. Sex and the Sugar Daddy: three women’s perspectives. In: Africa Eye Series. Online. BBC. Available from: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-45398826.

- Kibira, S.P., et al., 2014. Contraceptive uptake among married women in uganda: does empowerment matter? African Population Studies, 28, 968–975. doi:https://doi.org/10.11564/28-0-572

- Kiggundu, A.T., 2014. Constraints to urban planning and management of secondary towns in Uganda. The Indonesian journal of geography, 46 (1), 12. doi:https://doi.org/10.22146/ijg.4986.

- Lesch, E. and Kruger, L.-M., 2004. Reflections on the sexual agency of young women in a low-income rural South African community. South African Journal of Psychology, 34 (3), 464–486. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/008124630403400308.

- Lexico, ed., 2019. Dictionary.com and Oxford University Press.

- Lincoln, Y.S., Lynham, S.A., and Guba, E.G., 2011. Paradigmatic controversies, contradictions, and emerging confluences, revisited. In: N.K. Denzin and Y.S. Lincoln, eds. The Sage handbook of qualitative research. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications, 97–128.

- Locke, K., Feldman, M.S., and Golden-Biddle, K., 2015. Discovery, validation, and live coding. In: K.D. Elsbach and R.M. Kramer, eds. Handbook of qualitative organizational research. Innovation pathways and methods. New York: Routledge, 371–380.

- Mackay, H., et al., 2018. Doing things their way? Food, farming and health in two Ugandan cities. Cities & Health, 1–24. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/23748834.2017.1414425.

- Mackay, H., 2018. Mapping and characterising the urban agricultural landscape of two intermediate-sized Ghanaian cities. Land use policy, 70, 182–197. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.10.031

- Mackay, H., 2019a. A feminist geographic analysis of perceptions of food and health in Ugandan cities. Gender, Place & Culture, 26 (11), 1519–1543.

- Mackay, H., 2019b. Food sources and access strategies in Ugandan secondary cities: an intersectional analysis. Environment and urbanization, 31 (2), 375–396.

- Mackay, H., 2019c. Food, farming and health in Ugandan secondary cities. (PhD Doctoral thesis. Compilation). Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden. Available from: http://umu.diva-portal.org/.

- Marmot, M., 2005. Social determinants of health inequalities. The Lancet, 365 (9464), 1099–1104. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)74234-3.

- Marmot, M., et al., 2008. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health, on behalf of Commission on Social Determinants of Health. The Lancet, 372 (9650), 1661–1669. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61690-6.