ABSTRACT

Africa is undergoing rapid urbanisation with migration into informal settlements. Exposure to these environments is associated with a rise in infectious and non-communicable diseases. Addressing these urban health challenges will require collaboration across sectors that influence health. However, the siloed nature of policymaking means that little is known about the barriers and facilitators of integrated intersectoral policy approaches for improving health through urban planning and development. Furthermore, the transdisciplinary research methodological approaches to establishing intersectoral collaboration are not well documented in Africa. We utilised participatory methods to engage a variety of stakeholders in the co-design and conduct of a transdisciplinary workshop. Through co-development processes, this workshop was designed to explore stakeholder perspectives on urban health priorities in Douala municipalities and experiences of intersectoral collaboration. We describe the process and experience of co-creation of the workshop agenda between academic, policy, private and civil society partners. We further present stakeholder experiences of intersectoral collaboration prior to the workshop, convey their understanding of the urban drivers of ill health, and discuss perspectives on strategies to mitigate these health risks through human settlement intervention. This study documents the development of a participatory transdisciplinary approach to urban health in rapidly urbanising Africa.

Introduction

Africa’s rapid urbanisation is contributing to the growth in informality, as many people migrate into urban slums and informal settlements (UN-Habitat Citation2015). This includes both sub-Saharan as well as some North African countries such as Algeria (from 59.9% to 72.6%; 2000–2018) and Morocco (53.3% to 62.4%; 2000–2018) experiencing rapid urbanisation, largely due to rural-urban migration (TheWorld Bank Citation2019). Informal settlements, evident across all regions of Africa (UN-Habitat Citation2018) are characterised by high poverty rates, overcrowding, and poor housing conditions, including poor waste removal, sanitation and ventilation (United Nations Human Settlements Programme Citation2013). These conditions have been linked to the persisting presence of infectious diseases, and increasing burden of chronic illnesses, injuries, mental disorders and poor nutrition (World Health Organization/UN-Habitat Citation2010). Despite the importance of health and wellbeing in sustainable urban development strategies, health is largely not considered within the housing policy agenda. This is partly due to the siloed vertical nature of policymaking, which results in a lack of policy coherence between the housing and health sectors (Leppo et al. Citation2013, Rudolph et al. Citation2013). Addressing the current high burden of infectious diseases in Africa and the growing prevalence of chronic multimorbidities urgently requires new thinking around housing and human settlement strategies.

If Africa’s rapidly growing urban population is to enjoy living in safe and sustainable cities by 2030, policy strategies need to measurably improve living conditions and, subsequently, the health of the population, particularly the urban poor. The opportunities for intersectoral approaches through the coordination of health-enhancing housing, urban planning and environmental health regulation in African cities, are particularly important for contributing towards efforts to meet Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 11, which seeks to ‘make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable’ (United Nations Citation2017). Urban planning – as an inclusive, integrated decision-making process – can give a voice to those who often do not participate in urban and territorial decision-making and respond to the needs and vulnerabilities of different population groups (particularly the urban poor, women, children, older adults, informal sector workers and migrants). Thus, applying a health ‘lens’ in urban and territorial planning (UN-Habitat Citation2017) can reveal synergies to achieve environmental, economic, health and social targets, to ensure that the New Urban Agenda (NUA) – a global agenda for sustainable urban development and management that compliments the implementation of the SDGs (UN-Habitat Citation2016) – delivers healthy, safe, inclusive, and equitable cities. Cities can play vital roles in addressing health and social inequity; and greater policy coordination on housing and urban planning could contribute to improving health outcomes, as well as reducing neighbourhood crime and increasing economic development (Rudolph et al. Citation2013).

The population of Douala, the economic capital of Cameroon, is projected to triple by 2035 with an average annual rate of population growth estimated at 5% over the past 30 years, well above the national rate of 2.8% (Priso Citation2017). This population increase has not been matched by increased availability of affordable housing. Currently, over 70% of the population live in informal settlements (Mbaha et al. Citation2013), with both urban poor and middle-class residents living under conditions of informality due to poor housing and tenure policies. Douala metropolis is made up of six municipalities, with each headed by a Mayor duly elected by the municipal councillors. Municipalities’ responsibilities are to improve the living conditions of their citizens by making sure they have access to basic socio-urban infrastructures (Presidency of the Republlic of Cameroon Citation2009). However, these municipalities are under the authority of a Government Delegate appointed by the President of the Republic. It is this Government Delegate who administers the city. The local Agenda 21 for Douala, developed in 2010 by the Douala City Council (DCC), identifies development of urban planning and sustainable housing as a priority. However, the agenda has a poor focus on health outcomes and the health impact assessment of human settlement policies. Given the unhealthy and unsafe environment of informal settlements, inhabitants are exposed to a range of risk exposures which contribute to a growing burden of infectious and non-communicable diseases (Sanou et al. Citation2015). The DCC have expressed the need to address urban challenges related to informal settlements in Douala. In addition, the paucity of data on the health of Douala informal settlement residents, and the weak collaboration between health and housing sectors in the urban planning represent a knowledge gap and opportunities for the development of innovative integrated approaches to address health and human settlement challenges.

A transdisciplinary research approach, which seeks to link scientific inquiry with context-specific societal challenges identified by non-academic stakeholders, can assist in guiding the co-production of new useable knowledge for addressing complex urban health challenges in cities (Pohl et al. Citation2017). The co-production of knowledge process should not be driven by academic agendas, but should give particular attention to the needs of non-academic stakeholders who will need to act on the new knowledge, for example, through urban planning interventions (Clark et al. Citation2016). The process provides important opportunities for mutual-learning around key societal and urban problems identified (Cornell et al. Citation2013) and enabling new and relevant knowledge to be produced for the local context. The aim of this paper is to document the knowledge co-production process as a model for implementing transdisciplinary research approaches for collaboration.

As part of a larger multi-country research study exploring strategies and opportunities for intersectoral collaboration between human settlements and health sectors, we utilised participatory methods to engage a variety of relevant stakeholders in the co-design and conduct of a transdisciplinary workshop to explore perspectives on urban health priorities in Douala municipalities and experiences of intersectoral collaboration. A key component of this engagement was convening a workshop in Doula with stakeholders.

In this paper, we describe the process and experience of co-creation of a transdisciplinary workshop agenda between academic and policy partners. We further present experiences of intersectoral collaboration by stakeholders prior to the workshop, perceptions of multisectoral stakeholders on human settlement priorities across Douala municipalities, their understanding of the urban drivers of ill health, and perspectives on strategies to mitigate these health risks through human settlement intervention.

Methodology

This study used participatory methods to engage a variety of stakeholders in the co-design and conduct of a transdisciplinary workshop. Twenty-four stakeholders participated in the 3-day workshop, held at the Douala City Council building 12–14 March 2019, representing policymakers, academia, practitioners, private sector, and civil society.

Pre-workshop

Prior to the workshop, we sought to engage key stakeholders to co-develop the workshop. The stakeholders were generally grouped along the proposed Stakeholders groups of the International Guidelines on Urban and Territorial planning (IG-UTP) (United Nations Human Settlement Programme (UN-Habitat) Citation2015), namely representatives from National government, local government, civil society and their associations, and planning professionals and their associations. The following three-step process was used:

Identifying stakeholders: We began by building a collaboration with the Douala City Council (DCC). A formal meeting was then organised at the city hall, to which actors active in the management of the city were invited by the DCC. After presenting the proposed project on integration of health and human settlement policies, we sought to jointly identify stakeholders best suited to engage in the transdisciplinary workshop. Through this process, we identified five categories of stakeholders across a variety of sectors: policymakers, planning practitioners, territorial governance actors, academia, and civil society.

Engaging with identified stakeholders: In total, fifteen stakeholders were identified and formally invited to attend a large stakeholder engagement meeting. Two stakeholders formally declined, and six stakeholders confirmed their participation in the meeting. These attendees represented the Douala Urban Community, the University of Douala, Delegate Public Health, Delegate Housing and Town Planning, Delegate Urban and Rural Planning and Development Mission, and a private non-government organisation. The meeting was held from 16 to 18 October 2018. The first step in engaging stakeholders identified was to provide an opportunity for stakeholders to reflect on and share with others their experience in city management and practice. Next, the DCC team shared the city’s vision for town planning. Thirdly, the research team shared the aims of the project and the overall goal to contribute towards making Douala a healthy and sustainable city. At this point, invited stakeholders were asked to reflect on whether they shared the vision of the city as presented by the DCC and the goal of the research programme; and to share their thoughts on this. Agreement was collectively recognised as an indication of the desire to proactively engage with the workshop and subsequent research collaboration. These engaged stakeholders, as well as the original list of identified stakeholders, were subsequently invited to attend the transdisciplinary workshop with members of the DCC and the wider research team. The typology of stakeholders who were identified for engagement is represented in .

Table 1. Typology of stakeholders identified for the workshop

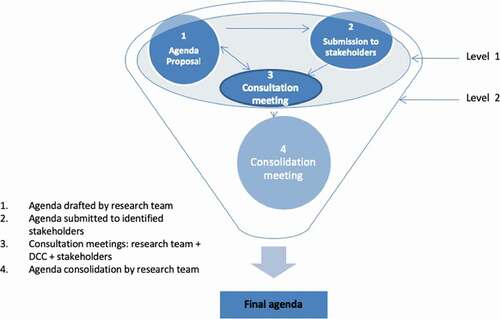

Co-designing the workshop: In recognition of the vital role that workshop delegates would play in research partnership and as implementers and advocates of healthy public policies, we sought to ensure the workshop programme addressed their needs and knowledge gaps to engender stronger partnerships. Following the engagement step (Step 2), the research team drafted an initial agenda, and invited engaged stakeholders to review and propose edits to the agenda. The process of designing the workshop was interactive and participatory at all levels (). This process included engaged stakeholders, the DCC team and the research team. Initial comments on the draft workshop agenda were incorporated into a second version which was then revisited in subsequent consultation meetings with the stakeholders until consensus was achieved. This co-developed agenda was then reviewed by the research team in a consolidation meeting that sought to ensure the key objectives of the research were covered by the workshop, and to ensure that the required logistics were feasible.

Workshop structure design

In planning the structure of the workshop, we utilised three approaches to ensure the workshop was interactive.

Knowledge sharing: We recognised that stakeholders came to the workshop with different levels of knowledge on global and local trends in urban planning, health, and the interaction between these; as well as the global frameworks and resources that exist to guide development of healthy planning policies. As such, a key component of the workshop involved talks by the research team, UN-Habitat representatives, and Douala policymakers and academics. These sessions covered essential dimensions of urban and territorial planning. These included providing information on global urban trends and global frameworks, i.e. SDG, NUA, World Health Organization (WHO) (World Health Organization/UN-Habitat Citation2010) and UN-Habitat (Citation2017) frameworks; as well as grounded experiences and case studies of the implementation of these frameworks. One case study was presented for Cape Town, where a similar study integrating health in human settlements policies was being conducted by the members of the project team. Case-studies relevant to the Douala urban development context were selected to illustrate the implementation of global frameworks into its specific context. In addition, local academic and policy stakeholders shared their local knowledge on the challenges of urbanisation in Douala, and strategies being implemented to address these.

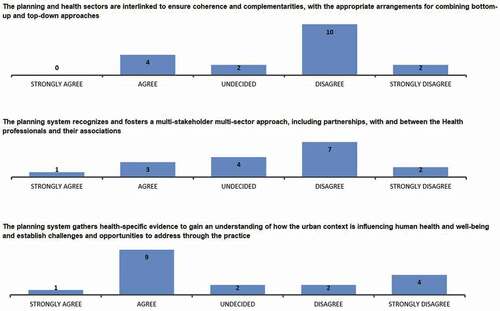

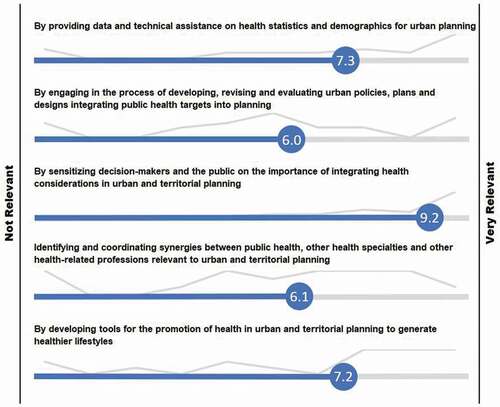

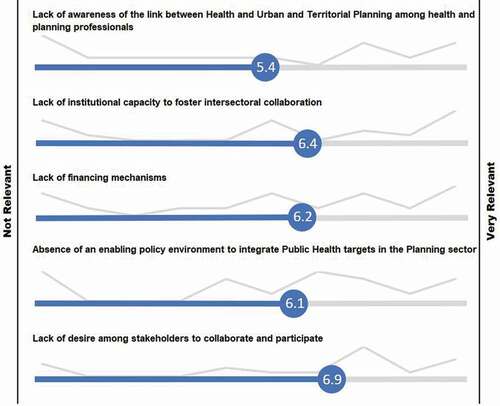

Interactive assessments: We utilised real-time surveys, to engage participants and facilitate interaction. The tool, CitationMentimeter, was used to conduct surveys that enabled participants to see in real time the response of all participants on screen. A pre-workshop survey was conducted at the start of the workshop to take a measure of participants’ perceptions on the role of health in urban planning, their experiences of intersectoral collaboration and their perspectives on challenges and opportunities for integrating health into urban planning policy. The survey explored participant perceptions using response scales. Participant responses to questions exploring perceptions on the role of health in urban planning were measured on a 5-point Likert scale with categories of ‘strongly agree’, ‘agree’, ‘undecided’, ‘disagree’ and ‘strongly disagree’. A 0–10 response scale (0 = not relevant; 10 = very relevant) was used for the questions exploring experiences of intersectoral collaboration and perspectives on challenges and opportunities for integration. Participants could indicate the degree to which they felt the statement was relevant to their work or situation. The results of the survey were automatically recorded in an Excel spreadsheet and were analysed using frequency distributions for the categorical data.

The second interactive survey was conducted at the start of the second day of the workshop and engaged participants to share their perspectives of Douala’s planning system; in particular assessing ongoing multistakeholder, multisector involvement in planning policies, and the ways in which the governance, accountability mechanisms of planning policies are aligned for health creation. This survey operationalised the 12 planning principles of urban and territorial planning (United Nations Human Settlement Programme (UN-Habitat) Citation2015) and helped to identify the opportunities and challenges at the local level.

A third real-time survey conducted at the end of the workshop assessed whether there were any changes in perceptions of the role of health in planning and vice versa, and any learnings on tools for integrating these sectors. Responses were measured using scale and multiple-choice response formats.

(3) Working group discussion: Over the course of the workshop, we sought to explore participants’ perceptions of urban challenges in the different Douala municipalities represented; to probe their understanding of health risks associated with these urban challenges, and lastly to collectively develop strategies to mitigate these health risks. These were conducted through working group discussions, which were divided into two sessions.

The first working group session was run after knowledge-sharing talks from the research team on urbanisation challenges in Africa generally, and from a Douala policymaker presenting a local perspective on urbanisation challenges in Douala. In this first session, participants were split into groups with each group representing one of four Douala municipalities represented. The aim was for workshop delegates across sectors to work together to identify and prioritise human settlement challenges experienced in their municipality. The multisectoral distribution of stakeholders in these groups put into practice the concept of intersectoral collaboration as each group comprised representatives from health and planning/human settlements sector. The urban priorities were then presented by a rapporteur from each group in plenary.

The second working group discussion followed further knowledge-sharing presentations from a Douala policymaker on housing challenges, from a local public health researcher on health needs of the Douala population, and a lecture on the interlinkages between the built environment and health. In this second break out group discussion, the group categories were the top urbanisation challenges identified across all municipalities in the first discussion. Delegates were asked to join a group that best represented their area of interest and were challenged to consider the ways in which the health issues presented are linked to their selected urban human settlement challenge. This session was designed to interactively explore health issues related to the urban challenges previously identified, with each group comprising participants with diverse skills and from across municipalities. Each group was encouraged to brainstorm strategies to be used for mitigating the health risks from the identified urban exposures.

Results

Pre-workshop motivations, perceptions, and experiences of intersectoral collaboration

Participants were asked about their primary motivation for attending the workshop on day 1. Of the 20 responses received, the most common motivation (9/20) was to better understand the relationship between health and planning, and the importance of intersectoral collaboration. A further 20% were primarily motivated to participate in order to learn about case studies on health and human settlements, and to equip themselves with tools and strategies for intersectoral collaboration. When asked about experiences of intersectoral collaboration between health and human settlement sectors prior to the workshop, 53% reported having never worked with the other sector.

Perspectives of participants on integration between health and human settlement sectors in Douala are presented in . Whilst the majority of participants felt that there was poor linkage between planning and health sectors, the majority (10/18 responses) agreed that the planning system gathered evidence of relevance to health. To explore pre-existing attitudes on the role of health in human settlements planning, using a Likert 0–10 scale from not important to very important, participants were asked to express the ways in which they thought health professionals can contribute to urban and territorial planning. shows that the three most important roles that participants felt health professionals should play are 1) to raise awareness of the importance of integrating health into planning, 2) to provide assistance on health statistics for urban planning, and 3) to develop tools to facilitate this integration. Lastly, when asked about the biggest challenges faced in intersectoral health and planning integration, a ‘Lack of desire among stakeholders to collaborate’, and ‘Lack of institutional capacity to foster intersectoral collaboration’ were felt to be most pertinent ().

Human settlements priorities across Douala municipalities

The results from the first working group discussion are summarised in , highlighting common themes and challenges highlighted across the four municipalities represented. Responses covered across three themes:

Basic Services: sanitation, waste management, health services and access to potable water;

Urban Planning: challenges relating to the planning and implementation of urban planning policies within the wider built and natural environment; and

Public Behaviour: including wider social challenges that present barriers to policy implementation and sustainable urban development.

Table 2. Human settlements challenges identified for Douala Municipalities A–D

Health risks associated with human settlements challenges in Douala

In the second working group session, for each of the urban environment challenges prioritised, participants were invited to consider ways in which these challenges influence population health in Douala. Five key categories of urban health challenges were identified. These are presented along with the urban environment challenges perceived to be associated with these health risks.

Infectious disease (vector/water-borne, zoonotic)

Sanitation & waste: Municipalities reported a proliferation in vector and waterborne diseases that were perceived to be linked to sanitation challenges across Douala. Flooding and insufficient drainage were thought to increase the spread of waterborne diseases. An absence of water treatment plants and insufficient equipment in the management of the drainage system was also reported as contributing to infectious disease. Stakeholders suggested that blocked drainage systems were further exacerbated by poor household waste management increasing the risk of infectious diseases. In addition to household waste, the exposure of residents to industrial waste due to poor waste management was identified as posing a risk for infectious disease.

Water access: Whilst the quality of potable water at their sources was thought to be good, stakeholders believed that poorly maintained water delivery infrastructure in Douala result in suspended particles that act as pollutants and produce environments that encourage vector breeding. It was noted that poor households were particularly affected as they are likely to seek alternative affordable sources of water of poor quality.

Urban mobility: The stagnant water found in potholes along the transport corridors was perceived to act as breeding grounds for vectors and bacteria contributing to malaria and other waterborne diseases.

Urban disorder: The high prevalence and negligence of unkempt domestic animals was cited as a health risk for infectious disease transmission. In addition, the sale of perishable food in unhygienic unlicensed market environments was also perceived to be a contributor to the burden of infectious disease.

Mental health

Water access: A lack of access to water was also suggested to be linked with psychological stress and mental wellbeing, particularly amongst the poor.

Urban mobility: Stress caused by transport challenges was listed as a health concern thought to contribute to poor mental health.

Insecurity & safety: Within the built and natural environments, safety concerns identified related to urban flooding, landslides, high crime rates, and these were thought to increase the risk of mental illness, particularly stress and depression.

Injury

Urban mobility: Transport corridors were suggested to be linked with high levels of accidents and trauma.

Insecurity & safety: Housing-related risks to safety included concerns around poor-quality sand used in housing construction; poor quality engineering and architecture, and construction of housing in high-risk zones due to the spontaneous occupation of space. Exposure to these risks was perceived to be associated with fire and road accidents, and resulting injuries contributing to loss of life.

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs)

Urban mobility: The number of vehicles on the roads were thought to contribute to respiratory illnesses and cardiovascular problems due to pollution.

Insecurity & safety: In addition, exposure to poorly constructed housing was understood to contribute to illnesses related to humidity and heat.

Emergency healthcare access

Urban mobility: Stakeholders drew attention to the slow response to emergencies, due to poor road infrastructure compounding the challenge of insufficient ambulances in some municipalities.

Strategies proposed to mitigate urban health risks

As part of the second working group discussion, participants were asked to brainstorm and propose strategies to mitigate the health risks from urban exposures identified. Solutions proposed fell into three categories: government-led action, awareness-raising action by individuals, collective action by society (communities and private sector). As shown in , the majority of interventions proposed were government-led. In discussions relating to interventions that were exclusively private (sale of sachet water), stakeholders reflected that this strategy would likely not be affordable and could further pose health risks if poor quality water was to be sold. In addition, whilst the urban contributors to health risks identified cut across all urban exposure categories, the majority of strategies proposed focused on intervening in water, waste and sanitation exposure categories.

Table 3. Strategies proposed by participants to address urban health risks identified

Discussion

Participatory methods

The importance of engaging stakeholders early in co-design was underscored in our experience of organising this intersectoral workshop. Having co-developed the agenda, a key concern was whether the participation of engaged stakeholders would be as expected given competing priorities for their time. We thus continued to engage with stakeholders in the run up to the workshop, to remind them of the rationale for the workshop and the potential benefits of continued participation.

Meeting the collective needs of all stakeholders is an important aspect of co-designed, transdisciplinary research. This research has shown that as a significant change-agent, transdisciplinary research falls at the intersection between scientific process, through which scientific research is conducted to understand a particular societal challenge, and the societal process, in which a societal issue is identified by actors who seek to understand and practically address it, for example, through interventions and policy (Pohl et al. Citation2017). The significance of ‘co-designed’ research is that it acknowledges the blending of scientific and societal knowledge and processes around an identified challenge, thereby providing a holistic, solution-focused approach that can benefit participating stakeholders (Moser Citation2016). Engagement workshops such as these therefore have the potential to initiate an ongoing participatory process between academic, state and civil society actors for exploring the possibilities for research-policy partnerships and collaborations (Oni et al. Citation2019).

In addition to the co-design approach, we also found that utilising participatory approaches to obtain information from participants was valuable to setting the scene for the workshop including an understanding of prior experiences, perceptions and expectations. The real-time sharing of these survey results further served to engage participants as, after responding to each question, they could instantaneously compare their perceptions to those of other participants which sparked interest and focused discussion based on the collective experiences in the room. In addition, the survey results assisted in identifying gaps and areas for improvement, and this also contributed to focused discussion.

Perceptions of urban health challenges in Douala

Participants acknowledged that a possible contributing factor for the reported lack of experience in intersectoral collaboration is the general lack of desire or willingness to engage and collaborate across sectors, which may be rooted in commitments to sector priorities and mandates. Lessons learnt from global efforts to implement intersectoral health policies, particularly those endorsed by the WHO, suggest that the structuration of many governments into distinct sectors, each held accountable with prescribed mandates and reporting targets, does not lend itself to intersectoral collaboration (Bacigalupe et al. Citation2010). However, Africa does have some examples of successful implementation of intersectoral efforts to address urban health, particularly with One Health – an approach seeking to integrate efforts across health, environmental and veterinary sectors as a form of preparation for tackling rising pandemics, such as emerging zoonotic diseases (World Health Organization Citation2007). Uganda, Nigeria and Tanzania have all participated in implementing a One Health intersectoral approach to addressing human African trypanosomiasis (or ‘sleeping sickness’), the influenza A (H1N1) virus and rabies, respectively (Okello et al. Citation2014). However, their efforts highlight the importance of modifying global intersectoral collaboration models for the local or regional context, in line with societal issues which can be identified through bottom-up transdisciplinary research and supported by an institutional ownership of the collaboration (Okello et al. Citation2014).

Participants’ understanding of health risks influenced by urban challenges was diverse, ranging from infectious diseases and mental health to other NCDs and injury. The notion of equity was expressed both in how these challenges influence urban residents and in strategies to mitigate these. Urban mobility emerged as a cross cutting urban challenge as it was cited across all categories of health risk. However, despite knowledge sharing on intersectoral action, the strategies that were proposed to mitigate these urban health challenges were largely siloed, focused on water, waste and sanitation. This likely reflects the current siloed structures within which participants work, as well as the lack of experience with intersectoral collaboration. This is corroborated by findings from the planning assessment in Douala, where participants strongly perceived the lack of institutional capacity to foster intersectoral collaboration as a significant challenge to integrating health into human settlement policies. Furthermore, the overwhelming perception by participants on the key role of health professionals in intersectoral collaboration to be ‘sensitisation of decision-makers and the public on the importance of integrating health considerations in urban and territorial planning’ points to the need for greater buy-in into this approach and for governance mechanisms to support intersectoral collaboration. Notably, no strategies were proposed to mitigate urban mobility, despite this challenge emerging as the only cross cutting urban exposure impacting all categories of urban health risks identified. Given the siloed nature of strategies proposed, this could be considered to reflect the complexity of a cross-sectoral approach that would be required to address urban mobility.

One approach that could be taken to ensure an urban challenge like urban mobility is relevant to a range of sectors is to dissociate it from the traditional, infrastructure-focused conceptual form (Lang et al. Citation2012). For example, a key question is to ask how this concept could be deconstructed into themes or ‘societal challenges’ that would require intersectoral collaboration from a range of sectors, such as transport, health, education and urban planning sectors (Lang et al. Citation2012). In addition, strategies to address a complex urban challenge, such as urban mobility, may require a little more than a top-down intersectoral approach. Participants identify the role that civil society can play in assisting with mitigating urban challenges, such as through the mobilising of community committees. This is supported by Chircop et al. (Citation2015) who argue that intersectoral collaboration to address complex challenges should also include bottom-up and top-down collaboration. Civil society can contribute highly relevant and valuable non-scientific knowledge, and will be a key actor in influencing the sustainability of the intervention on the ground (Lang et al. Citation2012, Mauser et al. Citation2013). The importance of collaborating with civil society has been acknowledged by Kenya who are seeking to implement a Health in All Policies approach to address health challenges through intersectoral action (Mauti et al. Citation2019).

Conclusion

This study has highlighted the need for intersectoral mechanisms to be established in order to develop and implement cross-sector action for urban health; as well as the need for greater awareness of tools to facilitate better collaboration between sectors. Outputs of this participatory process including a workshop report results from the interactive assessments, presentations from the knowledge-sharing sessions, and relevant UN-Habitat tools and reports were shared with participants to support collaborative urban planning for improving urban challenges in local contexts.

The current structuration of government organisations into sectors, insufficient willingness to engage intersectorally around key urban health challenges, and strict sector mandates and targets, are some examples of barriers to intersectoral collaboration. However, transdisciplinary research lessons provide a number of strategies to overcome these. Firstly, participatory methods that involve knowledge sharing and the co-designing of research questions and stakeholder engagements can assist in ensuring collaboration is relevant and beneficial to all sectors and actors involved. Secondly, the deconstruction of health or built environment concepts into transdisciplinary societal challenges that require intersectoral engagement can also assist intersectoral collaboration efforts. Thirdly, the mobilising of non-state actors such as civil society for the design and implementation of interventions, thereby demonstrating a top-down and bottom-up collaboration, can assist in maintaining intervention sustainability and reduce the burden of action on resource-limited governments. Finally, there is great potential for co-designed workshops such as these, organised in other contexts, to contribute to refining the methodology described further; as well as to initiate participatory processes to explore intersectoral collaboration and researcher-policy partnership opportunities. Such activities would serve to build the evidence base required to inform contextually relevant models that aim to improve integrated urban governance in the planning of cities in Africa specifically and in rapidly growing cities across the global south more broadly.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Amy Weimann

Amy Weimann is a PhD student at RICHE.

Blaise Nguendo-Yongsi

Blaise Nguendo-Yongsi is an Associate Professor in Epidemiology at University of Yaoundé.

Christopher Foka

Christopher Foka is a student at University of Yaoundé.

Uilrich Waffo

Uilrich Waffo is a Research and Evaluation specialist.

Pamela Carbajal

Pamela Carbajal is an urban health and regional planner consultant at UN Habitat.

Remy Sietchiping

Remy Sietchiping leads the regional and metropolitan planning unit at UN Habitat.

Tolu Oni

Tolu Oni is a Clinical Senior Research Associate at the MRC Epidemiology unit, University of Cambridge, founder of RICHE, and Honorary Associate Professor at the University of Cape Town.

References

- Bacigalupe, A., et al., 2010. Learning lessons from past mistakes: how can health in all policies fulfil its promises? Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 64 (6), 504–505. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2010.110437.

- Chircop, A., Bassett, R., and Taylor, E., 2015. Evidence on how to practice intersectoral collaboration for health equity: a scoping review. Critical Public Health, 25 (2), 178–191. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09581596.2014.887831.

- Clark, W.C., et al., 2016. Crafting usable knowledge for sustainable development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113 (17), 4570–4578. doi:https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1601266113.

- Cornell, S., et al., 2013. Opening up knowledge systems for better responses to global environmental change. Environmental science & policy, 28, 60–70. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2012.11.008.

- Lang, D.J., et al., 2012. Transdisciplinary research in sustainability science: practice, principles, and challenges. Sustainability Science, 7 (S1), 25–43. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-011-0149-x.

- Leppo, K., et al., 2013. Health in all policies: seizing opportunities, implementing policies. Helsinki, Finland. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/188809/Health-in-All-Policies-final.pdf [Accessed 24 Jul 2018].

- Mauser, W., et al., 2013. Transdisciplinary global change research: the co-creation of knowledge for sustainability. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 5 (3–4), 420–431. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2013.07.001.

- Mauti, J., et al., 2019. Kenya’s health in all policies strategy: a policy analysis using Kingdon’s multiple streams. Health Research Policy and Systems, 17 (1), 1–12. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-019-0416-3.

- Mbaha, J., Olinga, J., and Tchiadeu, G., 2013. Cinquante ans de conquête spatiale à Douala : D’héritage colonial en construction à patrimoine socio-spatial vulnérable aux risques naturels. Cinquantenaire de La Réunification Du Cameroun: Enjeux, Défis et Perspectives, 145-165.

- Mentimeter, Available from: https://www.mentimeter.com/ [Accessed 10 April 2020].

- Moser, S.C., 2016. Can science on transformation transform science? Lessons from co-design. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 20, 106–115. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2016.10.007

- Okello, A.L., et al., 2014. One health: past successes and future challenges in three African contexts. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 8 (5), 1–7. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0002884.

- Oni, T., et al., 2019. Breaking down the silos of universal health coverage: from building health systems to building systems for health for primary prevention of noncommunicable disease in Africa. BMJ Global Health. 4 (4), e001717.

- Pohl, C., Krütli, P., and Stauffacher, M., 2017. Ten reflective steps for rendering research societally relevant. Gaia, 26 (1), 43–51. doi:https://doi.org/10.14512/gaia.26.1.10.

- Presidency of the Republlic of Cameroon, 2009. DECRET 2009/055 DU 06 FEV 2009 Portant Nomination Du Délégué Du Gouvernement Auprès de La Communauté Urbaine de Douala. Cameroon: Douala Municipality.

- Priso, D.D., 2017. L’homme avance, la forêt recule: stratégies de production urbaine en zone périphérique de Douala et perspectives pour une ville durable. Yaoundé, Ed Cle, 193.

- Rudolph, L., et al., 2013. Health in all policies: a guide for state and local governments. Washington, DC and Oakland, CA: American Public Health Association and Public Health Institute. http://www.dors.it/alleg/newcms/201305/2006_HiAP_Filandia.pdf [Accessed 24 July 2018].

- Sanou, S., et al., 2015. Water supply, sanitation and health risks in Douala 5 municipality, Cameroon. Igiene e sanita pubblica, 71 (1), 21–37.

- The World Bank, 2019. Data – urban population (% of total population) – Morocco, Algeria, Middle East & North Africa. Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.URB.TOTL.IN.ZS?locations=MA-DZ-ZQ [Accessed 27 Sep 2019]

- UN-Habitat, 2015. Habitat III issue papers 22 – informal settlements. doi:https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v5i0.19065

- UN-Habitat, 2016. Habitat III the new urban agenda. Available from: http://www.eukn.eu/news/detail/agreed-final-draft-of-the-new-urban-agenda-is-now-available/. [Accessed 25 July 2018]

- UN-Habitat, 2017. Implementing the international guidelines on urban and territorial planning 2015-2017. Nairobi: United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat).

- UN-Habitat, 2018. Working for a better urban future: annual progress report 2018.

- United Nations, 2017. Sustainable development goals. Available from: http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/. [Accessed 6 Dec 2017].

- United Nations Human Settlement Programme (UN-Habitat), 2015. International guidelines on urban and territorial planning. Nairobi: UN Human Settlements Programme.

- United Nations Human Settlements Programme, 2013. Planning and design for sustainable urban mobility: global report on human settlements 2013. New York: Routledge. doi:https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315857152.

- World Health Organization, 2007. Integrated control of neglected zoonotic diseases in Africa: applying the “One Health” concept. Vol 84.

- World Health Organization/UN-Habitat, 2010. Hidden cities: unmasking and overcoming health inequities in urban settings. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, The WHO Centre for Health Development, Kobe, and United Nations Human Settlements Programme. doi:https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2011.163634.