ABSTRACT

Globally there is increasing interest in making cities more liveable for all, a concept which aligns strongly with the UN Sustainable Development Goals. However, existing tools for tracking progress towards more liveable, equitable cities have been developed primarily for cities in high-income country contexts, while there is little guidance for cities in low- or middle-income country contexts. This partnership project is a capacity-building collaboration between RMIT University (Australia), the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration (Thailand), the Victorian Health Promotion Foundation (Australia), the UN Global Compact – Cities Programme, and the Victorian Department of Health and Human Services (Australia). The project’s aim is to develop a city-wide liveability indicators system for Bangkok for informing urban planning policy. Thus far, over 60 liveability indicators have been generated for Bangkok. Moreover, the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration has identified three Bangkok districts for deeper interrogation. This project is developing scalable tools for monitoring liveability and strategically informing urban planning policy in a low-to-middle income city context, with relevance to other cities. It has established an international liveability network and deeper understanding of shared challenges and created ongoing opportunities for capacity building and reciprocal learning.

Introduction

Globally there is a major commitment, with growing urgency, for countries and cities to prioritise health and wellbeing, reduce poverty, and support environmental resilience. Most recently, this agenda has been championed through the UN’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals, commonly known as the SDGs, which are embedded within the New Urban Agenda (World Health Organization Citation2016, United Nations Citation2017). The vision set by the SDGs harnesses the policy, practice, and academic evidence on urbanisation, population health, and the environment, and is designed to be relevant to all sectors and across low-to-high income countries. The New Urban Agenda and the SDGs (supported by associated targets and indicators) provide important frameworks for measuring and monitoring cities’ progress across a range of health and social outcomes; however, critics have noted both frameworks focus on outcomes and a lack of guidance around the practical steps cities will need to take to improve these outcomes. For example, scholars have noted a lack guidance around specific urban policies and their trajectories, infrastructure, and investments needed to achieve more sustainable outcomes, and how to prioritise of the ambitious aspirations laid out in the New Urban Agenda (Garschagen and Porter Citation2018, Giles-Corti et al. Citation2019). Still, the common language of the SDGs has been found to stimulate greater cross-sectoral collaboration in cities by providing a ‘rallying point’ for diverse sectors and interest groups, with a strong focus on inter-sectoral partnerships (Horne and Nolan Citation2018, Horne et al. Citation2020).

In parallel to the development of the SDGs, the aspiration of making cities more ‘liveable’ has become a key priority for many cities (Lowe et al. Citation2015). The notion of urban liveability has been popularised by international liveability rankings, which can be used to guide business investment, tourism, and employee remuneration (e.g. the Economist Intelligence Unit’s Global Liveability Index) (Badland et al. Citation2014). In contrast to such city rankings, urban liveability frameworks developed from a public health perspective seek to identify the tangible aspects of urban policy and infrastructure which shape residents’ health and urban sustainability outcomes (Lowe et al. Citation2015). Drawing upon the international evidence around cities and health, our previous work has conceptualised liveability as ‘safe, attractive, socially cohesive and inclusive, and environmentally sustainable, with affordable and diverse housing linked to employment, education, public open space, local shops, health and community services, and leisure and cultural opportunities, via convenient public transport, walking, and cycling infrastructure’ (Lowe et al. Citation2015, Badland et al. Citation2015). This social determinant of health-centred definition is underpinned by the long-standing recognition that cities are a key setting that shapes population health, which is embodied in the global Healthy Cities movement and the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion (Giles-Corti et al. Citation2016, World Health Organization Citation2020). Liveability resonates with the SDGs, particularly Goal 11, which aims to ‘make cities inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable’ (United Nations Development Programme Citation2015).

In strengthening urban governance systems, delivering infrastructure, and improving urban liveability, different country contexts (and their cities) face diverse challenges. For example, many cities located in low-to-middle income countries (and especially cities located in Asia and Africa) face the fastest rates of urbanisation, compounded with accelerated population growth (UN Department of Economic Citation2018). Of relevance here is Bangkok, Thailand. Like many other Asian capital cities, Bangkok has experienced rapid social and economic growth over recent decades, with accelerating immigration from other Thai provinces and ASEAN member states. This growth presents new opportunities as well as pressures for the city. For example, while investments have been made in education, providing equitable access to high-quality schools remains difficult. Major challenges also relate to growing social inequity, unemployment, and precarious work conditions, traffic congestion, and ensuring healthy, sustainable food sources (Alderton et al., Citation2019). There is concern about inequitable access to both hard infrastructure (i.e. appropriate sanitation, clean drinking water, mass transit systems) and soft or ‘social’ infrastructure (e.g. health and social services). Beyond these challenges are those that all cities – including those located in high-income countries – must address, such as mitigating and adapting to the effects of climate change.

Pilot project

Our previous research has contextualised the notion of liveability for Bangkok and other cities in low-to-middle income country contexts (Alderton et al., Citation2019, Alderton et al. Citation2018). Briefly, a group of BMA technical leaders visited RMIT University in May 2017 to participate in the Urban Liveability and Resilience Program, which was structured as a capacity development and training program run by the UN Global Compact – Cities Programme with support from urban scholars at RMIT University. The Cities Programme is the urban arm of the UN Global Compact – the world’s largest corporate sustainability initiative – and is hosted by RMIT University. As part of this program, BMA technical leaders participated in an Urban Liveability Workshop, during which they collectively refined an urban understanding of the concept of liveability to suit Bangkok’s context and identified the key liveability issues facing the city (UN Global Compact Cities Programme Citation2017). Following this workshop, the partners worked collaboratively to define liveability for the Bangkok context, prioritise the domains and indicators of interest for the city (the Pilot Bangkok Liveability Framework), and identify potential data custodians to populate the indicators (Alderton et al., Citation2019, Alderton et al. Citation2018). Findings from the pilot project have directly informed this larger project (Measuring, Monitoring, and Translating Urban Liveability for Bangkok, hereafter referred to as the ‘major project’). For example, BMA leaders involved in the pilot work showed a strong desire to have available a range of spatially derived liveability indicators to inform urban planning decision-making in Bangkok. There was also an identified need to improve knowledge of existing local spatial data infrastructure and expertise, as well as opportunities for building capacity (e.g. in sourcing fine-grained and open-source spatial data) (Alderton et al., Citation2019). These issues were included as core activities in the major project round.

Liveability and Bangkok’s 20-year development plan

The BMA Department of Strategy and Evaluation led the alignment of the liveability indicators identified in this project to the 20-year Development Plan for Bangkok (2013–2032). The Department of Strategy and Evaluation is responsible for work relating to policy and urban planning, sourcing data, and information management. A senior policy officer in this department led the mapping of liveability indicators against the 20-year Development Plan, and based on this work, further conceptualised liveability as falling under four dimensions for Bangkok. These four dimensions include city problems impacting health and wellbeing; health-promoting environments; enhancing quality of life; and social development. These four dimensions are being used within Bangkok’s 20-year Development Plan to frame strategy and build understanding about how urban planning and liveability relate to health and wellbeing.

Study aims

The aim of this paper is to describe the development, coordination, and learning outcomes from the partnership between the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration (BMA) based in Bangkok, Thailand, and academic and policy partners located in Melbourne, Australia. This paper will describe the: (1) development of the partnership; (2) application of the SDGs and liveability to frame the activities; and 3) training and reciprocal learning outcomes that have arisen from the partnership.

Methods

Partnership development

This partnership is a capacity-building collaboration led by RMIT University in Melbourne, Australia, partnering with the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration (BMA) in Thailand (http://www.bangkok.go.th/), the UN Global Compact – Cities Programme (https://citiesprogramme.org/), the Victorian Department of Health and Human Services (Australia; https://www.dhhs.vic.gov.au/), and the Victorian Health Promotion Foundation (VicHealth; Australia; https://www.vichealth.vic.gov.au/). The concept for the VicHealth Sustainable Development Goals partnerships was developed following a VicHealth forum in 2016 that identified cross-sectoral partnerships as being key to achieving specific SDG targets in the context of six emerging global megatrends (Hajkowicz et al. Citation2012). The forum brought together leading researchers, policymakers and practitioners, including the World Health Organization, the International Network of Health Promotion Foundations and the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (Hajkowicz et al. Citation2012). With support from the UN Global Compact – Cities Programme, the BMA initiated the partnership with scholars at RMIT University and the Victorian Department of Health and Human Services. This led to the pilot project and development of the Pilot Bangkok Liveability Framework (2017–2018) and continuation into the major project (2018–2020), which is the focus of this paper.

Both the pilot and major project have been endorsed by the Governor of Bangkok. Previous UN Global Compact – Cities Programme projects in other cities have shown that this senior-level commitment is critical in providing resources and momentum for SDG projects. A senior BMA staff member provides dedicated project management support and coordination between the BMA and the Australian-based team. Alongside these commitments, the BMA has established a partnership project steering committee that includes senior policymakers from diverse departments in the BMA, as well as two working groups. One working group focuses on identifying data custodians and sourcing spatial data, and the other on aligning the partnership work to the BMA’s policy and strategy. Both working groups are comprised of technical leaders from diverse BMA departments, including Strategy and Evaluation, Drainage and Sewerage, City Planning, Public Works, Environment, and Health, amongst others. A co-created bilingual Terms of Reference document enumerates the activities and responsibilities of the RMIT University team, BMA steering committee, and BMA working groups. Indeed, three Bangkok districts were identified for deeper interrogation by the BMA steering committee and working groups; these districts are of particular interest because of their high potential for reducing health and social inequities through infrastructure intervention.

Reciprocal learning as a guiding framework

Our approach to engagement is underpinned by a reciprocal learning framework, whereby knowledge is regularly shared in a two-way exchange between teams in Bangkok and Melbourne. Further, this partnership has been guided by an understanding that people living and working in a given context are best-suited to define the issues most relevant to the setting (Beran et al. Citation2017). Hence, activities have been framed to prioritise local knowledge and assessments of training needs in Bangkok at each stage. For instance, a delegation of BMA leaders, including the Governor of Bangkok, visited RMIT University in Melbourne in 2019. During this visit, leaders from Bangkok and project partners based in Melbourne identified liveability challenges that face both Bangkok and Melbourne (SDG Goal 17). These mutual challenges included: 1) delivery of key ‘social infrastructure’ (e.g. schools) to a growing population (SDG Goals 4, 9); 2) increased vulnerability to floods, heat waves, and extreme weather due to climate change (SDG Goal 13); 3) the need for good-quality, affordable housing for all residents (SDG Goals 10, 11); 4) traffic congestion, pollution, and long commuting times (SDG Goals 7, 9); and 5) providing more residents with local employment opportunities (SDG Goals 1, 8, 9). Building upon the pilot project’s Urban Liveability Workshop, this 2019 visit served to continue the dialogue between partners in Bangkok and Melbourne, reflect on project progress, and establish further priority areas for future reciprocal learning.

Iterative processes to develop and prioritise indicators

Prioritising the SDG-aligned liveability indicators for Bangkok was an iterative process led by two BMA working groups. The Pilot Bangkok Liveability Framework (Alderton et al. Citation2018) represents the BMA working groups’ initial prioritisation of the liveability indicators. For feasibility reasons, indicator priorities in the pilot project were those which could be readily measured and assessed – that is, those for which fine-grained and accurate spatial data were readily available in 2018. In the major project, indicators considered to be important by the BMA, but as yet unpopulated, were investigated. Local spatial datasets were shared by the BMA and these were supplemented with open-source local, national, and international datasets identified and harvested by a spatial analyst (RMIT). The resulting liveability indicators and corresponding spatial datasets were mapped to the SGDS and, where possible, SDG targets. Using this list, the BMA working groups held multiple workshops to discuss the face validity of the indicators and the appropriateness of the proposed datasets for use in their organization. The review of these indicators and auditing for face validity was an iterative process; after each BMA workshop, key issues raised by the BMA were reported back to the team at RMIT University for consideration. The spatial analyst at RMIT University kept in close communication with a senior BMA policy leader throughout the process of data sourcing, indicator calculation, and mapping to ensure data were appropriate for application in Bangkok. In this way, the indicators and their components were iteratively refined to better suit the needs of the BMA.

Results

Over 60 liveability indicators have been generated so far, and additional indicators have been earmarked for future data acquisition and monitoring by the BMA. Examples of liveability indicators, data sources, and relevant SDG targets and indicators are presented in (the full list of indicators is provided as Supplementary Material). As shown in , we found many of the liveability indicators were aligned with (i.e. were markers of, or had potential to contribute towards) several SDG targets, highlighting the potential of efforts to enhance liveability to simultaneously advance progress towards the SDGs.

Table 1. Examples of Bangkok liveability concepts, indicators, data sources used, and alignment to SDG targets

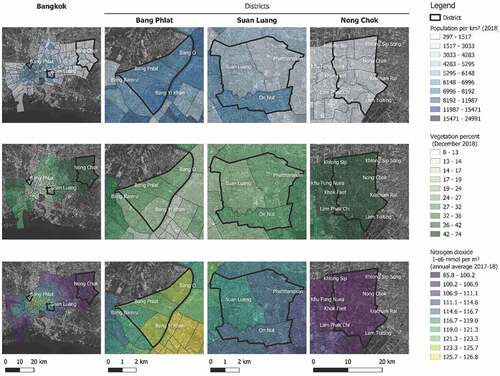

A key method of stimulating discussion for the appropriateness of indicators and related datasets has been the electronic delivery of static maps for selected indicators in districts of interest. shows an example of the static maps of two liveability indicators (nitrogen dioxide and vegetation coverage percent) alongside population density, prepared for three districts. As shown in these maps, the three districts represent one inner-city, relatively higher population density district (Bang Plat), one mid-city district (Suan Luang), and one outer-city, relatively lower population density district (Nong Chok). A spatial relationship is apparent, with population density and nitrogen dioxide both negatively associated with vegetation coverage percent. In general, population density and nitrogen dioxide are lowest on the urban fringes where vegetation cover is at its highest. However, there are exceptions to this trend, such as the densely populated sub-districts in Suan Luang, which also have higher vegetation cover and lower estimated annual average nitrogen dioxide.

Figure 1. Measuring, monitoring and translating liveability in Bangkok: project structure

Figure 2. Examples of static maps prepared for three case study sites in Bangkok

To support ongoing indicator use and capability building, the RMIT University team have developed a library of resources. Project documentation is produced in both static (PDF) and interactive (i.e. a project documentation offline HTML website) formats and is updated with each data package delivery. The resource supports the data packages with metadata, catalogued and searchable previews of resources, and examples of how to use and interpret indicators. Key project documentation and metadata have been translated into Thai language using Google Translate and checked for accuracy by a bilingual BMA colleague. With planned inclusion of case studies, tutorials and technical details on how to calculate and update indicators for Bangkok, this on-demand project documentation is intended to serve as a resource for ongoing capacity building and training in the BMA.

Discussion

This project has sought to create meaningful, scalable tools for monitoring Bangkok’s urban liveability through a cross-sectoral, international partnership bridging academia (RMIT University), local (Bangkok Metropolitan Administration), and state governments (Victorian Department of Health and Human Services), an international non-profit organization (UN Global Compact – Cities Programme), and a health promotion organisation (Victorian Health Promotion Foundation). Over 60 spatial indicators of liveability were created for Bangkok, and additional liveability indicators have been earmarked for future measurement and monitoring, once spatial data become available. Mapping these liveability indicators at a district- and subdistrict-level within Bangkok allows decision-makers and analysts within the BMA to map the delivery of urban infrastructure, identify disparities in access, and enable the identification of policies and infrastructure needed to promote healthy, sustainable urban futures. In doing so, these indicators respond to calls for data on SDG ‘inputs’ – the policies and infrastructure required to achieve SDG outcomes (Giles-Corti et al. Citation2019, Sachs et al. Citation2019) – that could contribute to achieving multiple SDGs within Bangkok. Indeed, scholars emphasise that the SDGs cannot be achieved without investments in the key built environment ingredients of a liveable city: public transport, adequate green spaces, access to sanitation and sewerage, and clean drinking water supply, among others (Sachs et al. Citation2019).

Similar to what others have suggested (Garschagen and Porter Citation2018, Horne and Growing Citation2018), we found that the SDGs provided a common language and shared understanding of the issues confronting Bangkok and cities in general. We found the SDGs (and in particular, SDG 11) lent further legitimacy to the concept of liveability, which resonates strongly with leaders in Bangkok and Melbourne, and aided in bringing together partners from health, governance, and urban planning backgrounds under a common mission. The benefits of working in partnership have been wide-ranging, and are perhaps most visible in the knowledge sharing between Bangkok-based and Melbourne-based partners, discussed below.

Utilising specific goals from the SDG framework in the project’s early stages highlighted the need for additional indicators for Bangkok, which were not previously captured in existing definitions of liveability developed for Australia and other high-income country contexts (Lowe et al. Citation2015, Horne et al. Citation2020). For example, indicators around urban infrastructure to provide clean drinking water (SDG Goal 6: Clean water and sanitation) (United Nations Sustainable Development Goals Citation2015) were included in Bangkok’s liveability framework, but have not typically appeared in urban liveability agendas developed for high-income country contexts. Yet, monitoring of water quality is also an issue for high-income countries such as Australia (Baum and Bartram Citation2018), particularly for those living outside capital cities (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare Citation2018). With anticipated public health impacts of increasing climatic instability including high risk of contamination of water supplies and associated water-borne disease outbreaks (Parise Citation2018, Steffen et al. Citation2018), such indicators may have increasing prominence in high-income countries’ urban futures. Such findings are hand-in-glove for reciprocal learning, stimulating the Melbourne-based team to consider the perspectives, norms and assumptions underpinning work originating in a high-income country. Methods originating from this partnership have informed Australian liveability work programs, including the regional Victoria and Global City Liveability indicator work programs (Davern et al. Citation2018a, Citation2018b, Citation2018c, Citation2019a, Citation2019b).

Working collaboratively across cities located in different continents, with distinct cultures and languages, posed both challenges and opportunities. For all partners, this required considering how to best engage with, and communicate across, differing organizational, cultural, and urban settings. We have endeavoured to be mindful of cross-cultural and inter-organizational norms, hierarchies, and systems. For the research team responsible for project management, this has required ongoing reflection about how the research program and engagement methods were unfolding. Where possible, bilingual documents and resources are being developed with the support of the BMA, external translation services, or automated Google Translate processes. Provision of bilingual documents and indicators was not initially within project scope; however, it became apparent early on that these were an important component of the partnership and capacity-building ambitions.

The project’s success has been facilitated by the active engagement of a Thai colleague, based within the BMA, who has acted as a cross-cultural interface between RMIT University and the BMA for knowledge sharing, stimulating enhanced engagement and reflective practice. Further, the involvement of the Governor of Bangkok and senior leaders in the project’s steering committee and working groups has been integral to ensuring Bangkok’s liveability indicators are embedded into strategic planning processes. Refining the indicators using an iterative rather than a linear approach has improved joint understanding of various issues ranging from data quality to indicator appropriateness and face validity, which serve to enhance the robustness of the tools prior to implementation.

Face-to-face meetings, both virtual and physical, have served an important role in building shared ownership over this project and stimulating reciprocal learning. As described earlier, the Urban Liveability Workshop was the starting point for establishing a trustful, open dialogue about, and shared understanding of, what liveability issues were important for Bangkok’s context. The 2019 visit to Melbourne by BMA leaders provided a timely opportunity to reflect on the project’s progress, raise questions for further investigation, and agree on shared priorities in terms of future areas for reciprocal learning and capacity building. Moreover, the importance of working agilely and flexibly has been highlighted through the COVID-19 global pandemic. This has required shifting two face-to-face visits to Bangkok to virtual meetings. The original purpose of these in-person visits was to gain a deeper understanding of Bangkok’s context, including site visits led by the BMA, and undertake capacity building and training activities for using and creating indicators. Instead, virtual training activities and resources are being provided, including a series of recorded webinars contributed by project partners.

Next steps

A key output of the project will be a suite of spatial liveability indicators for Bangkok, housed in an interactive, web-based portal. Ultimately, bilingual indicators linked to the SDG goals and specific targets will be made available to the BMA and research team through the IISD (International Institute for Sustainable Development) online portal (International Institute for Sustainable Development Citation2019). This online Tracking Progress portal provides the digital infrastructure for dissemination and visualisation (i.e. mapping, graphs, and tables) for the indicators developed for Bangkok. Once the indicators are integrated into the portal, the BMA spatial team and others will be able to access as required, with training provided through the online webinar library. Perhaps more importantly, in future, the BMA will be able to create and upload new datasets and indicators into the portal themselves as these assets become available. This means the indicators will remain current and relevant to the BMA’s ongoing strategic planning and liveability framework.

Conclusion

This partnership project has enhanced our international understanding of liveability within the context of the SDGs, and through genuine engagement has provided opportunities for reciprocal learning, capacity-building, and communities of practice. It has done this by stimulating an international liveability network through developing new collaborations and deeper understanding of shared and unique challenges, resulting in a suite of indicators that can be used in an ongoing manner to guide urban planning interventions to optimise liveability in Bangkok, and potentially elsewhere. Contextualising, prioritising, and operationalising liveability for low-to-middle income cities are critical for informing how urban planning can achieve SDG aspirations.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (24.7 KB)Acknowledgments

For their valuable insight and engagement throughout this project, we would like to acknowledge and thank our project partners: the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration, the Victorian Health Promotion Foundation, the Victorian Department of Health and Human Services, the UN Global Compact – Cities Programme.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data availability statement

Publicly available data utilised to produce the results presented in this paper have been referenced accordingly. Some of the data that support the findings of this study are available from the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Amanda Alderton

Amanda Alderton is a Research Officer and PhD Candidate at the Centre for Urban Research, RMIT University. She provides project management support to a partnership project involving an international collaboration between researchers and policymakers in Melbourne and Bangkok. Her PhD research investigates the relationships between the neighbourhood built environment and mental health in early childhood. She was awarded a Master of Public Health from the University of Melbourne (2018) and a Bachelor of Arts (Honours in History) from UC Berkeley (2013).

Carl Higgs

Carl Higgs is a research data scientist in the Healthy Liveable Cities group of the Centre for Urban Research at RMIT University. Having completed a Master of Public Health (epidemiology and biostatistics, 2015) and a Master of Biostatistics (2018) at the University of Melbourne, Carl brings key skills in statistical and spatial analysis and data visualisation to the Healthy Liveable Cities team. He has a particular interest in development of methods for measurement of built environment exposures for local neighbourhoods using diverse data sources to support equitable delivery of urban policies on planning and development.

Melanie Davern

Melanie Davern is Co-Director of the Healthy Liveable Cities Group and Senior Research Fellow at RMIT University. Melanie is also the Director of recently launched Australian Urban Observatory (auo.org.au) a new digital platform providing liveability indicators for the 21 largest cities of Australia available at municipal, suburb, and neighbourhood geographies. Melanie has specific expertise in indicators or the quantification of social, economic, and environmental measures of wellbeing that assess the social determinants of health as well as the translation of research knowledge into policy and practice.

Iain Butterworth

Iain Butterworth trained in community psychology, Dr Iain Butterworth has extensive experience in brokering, leading and implementing intersectoral policy, program, research, and capacity-building initiatives. Iain has worked in government, academe, NGOs, and the private sector. Working to integrate research, workforce development, and social entrepreneurship, he has engaged stakeholders extensively across numerous sectors and levels of influence to promote ecologically and socially sustainable urban design, build organisational capacity, and generate healthy public policy. Iain is an Honorary Associate Professor with the Centre for Urban Research at RMIT University. Since 2015, Iain has served as national President of the Australian Fulbright Alumni Association.

Joana Correia

Joana Correia manages Project Development for the UN Global Compact – Cities Programme International Secretariat, hosted by RMIT University in Melbourne, Australia. She plays a key role in brokering cross-sectoral partnered projects involving local government, private sector, and civil society organisations focused on sustainable development. She also designs and delivers cross-sectoral engagement initiatives. Joana has over 10 years of international experience spanning architectural practice, urban development, project management, and humanitarian aid. She holds a Bachelor Honours degree in Architecture (2008) and was awarded a Master of International Urban and Environmental Management from RMIT University (2015).

Kornsupha Nitvimol

Kornsupha Nitvimol is the Director of Human Resource and Social Strategy Division at the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration (BMA). She has been working in policy and planning at BMA for over 20 years. She played an important role in the process of marking the BMA 20-year Development Plan (2013 – 2032) and the first phase (5 years) of the 20-year-plan. Her recent research is on reducing social inequalities in Bang Phlat District. She works closely with international organizations and academic institutions including UNCRD, UNGCCP, and RMIT University. In 2010, she obtained an M.A. in international studies (development and cooperation) from Korea University.

Hannah Badland

Hannah Badland is a Principal Research Fellow based in the Centre for Urban Research, School of Global, Urban, and Social Studies at RMIT University in Melbourne, Australia and is the Deputy Director, Centre for Urban Research. She has worked on two NHMRC Centres of Research Excellence covering health, liveability, and disability and has been an investigator in a 14-country built environment and health study. Hannah was the inaugural Australian Health Promotion Association Thinker in Residence and is a Salzburg Global Fellow. Awarded a Vice Chancellor’s Senior Research Fellowship in 2017, Hannah examines how the built environment, through the social determinants of health, is connected to health, wellbeing, and inequities in diverse population groups internationally.

References

- Alderton, A., et al., 2018. Contextualising urban liveability in Bangkok, Thailand: pilot project summary report. Melbourne: RMIT University.

- Alderton, A., et al., 2019. What is the meaning of urban liveability for a city in a low-to-middle-income country? Contextualising liveability for Bangkok, Thailand. Globalization and health, 15. doi:10.1186/s12992-019-0484-8.

- Alderton, A. and Badland, H. Five liveability challenges Melbourne and Bangkok must face together 2019. Available from: https://cur.org.au/news/five-liveability-challenges-melbourne-and-bangkok-must-face-together/.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2018. Australia’s health 2018. Australia’s health series no. 16. AUS 221. Canberra: AIHW.

- Badland, H., et al., 2014. Urban liveability: emerging lessons from Australia for exploring the potential for indicators to measure the social determinants of health. Social science & medicine, 111, 64–73. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.04.003.

- Badland, H., et al., 2015. How liveable is Melbourne? Conceptualising and testing urban liveability indicators: progress to date. Melbourne: University of Melbourne.

- Bangkok Metropolitan Administration Strategy and Evaluation Department and Chulalongkorn University Faculty of Political Sciences, 20-year development plan for Bangkok Metropolis. Bangkok: Bangkok Metropolitan Administration.

- Baum, R. and Bartram, J., 2018. A systematic literature review of the enabling environment elements to improve implementation of water safety plans in high-income countries. Journal of water health, 16 (1), 14–24. doi:10.2166/wh.2017.175.

- Beran, D., et al., 2017. Research capacity building - obligations for global health partners. Lancet, 5. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(17)30234-5.

- Davern, M., et al., 2019b. A liveability assessment of the neighbourhoods of Manningham. Melbourne, Australia: RMIT University.

- Davern, M., Roberts, R., and Higgs, C., 2018a. Neighbourhood liveability assessment of the major townships of mitchell shire: beveridge; Broadford; Kilmore; Seymour; and Wallan. Melbourne, Australia: RMIT University.

- Davern, M., Roberts, R., and Higgs, C., 2018b. Walkability in Tasmania: assessment in the local government areas of Brighton, Clarence and Launceston. Melbourne, Australia: RMIT University.

- Davern, M., Roberts, R., and Higgs, C., 2018c. Neighbourhood liveability assessment of Shepparton: the application of indicators as evidence to plan for a healthy and liveable regional city. Melbourne, Australia: RMIT University.

- Davern, M., Roberts, R., and Higgs, C., 2019a. Neighbourhood liveability assessment of the rural city of Mildura. Melbourne, Australia: RMIT University.

- Garschagen, M. and Porter, L., 2018. The New Urban Agenda: from vision to policy and action. Planning theory & practice, 19 (1), 117–137. doi:10.1080/14649357.2018.1412678.

- Giles-Corti, B., et al. 2016. City planning and population health: a global challenge. Lancet, 388 (10062), 2912–2924. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30066-6.

- Giles-Corti, B., Lowe, M., and Arundel, J., 2019. Achieving the SDGs: evaluating indicators to be used to benchmark and monitor progress towards creating healthy and sustainable cities. Health policy, 124(6), 581–590. doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2019.03.001. in press.

- Hajkowicz, S., Cook, H., and Littleboy, A., 2012. Our future world: global megatrends that will change the way we live. The 2012 revision. Australia: CSIRO.

- Horne, R. and Nolan M., 2018. Growing up or growing despair? Prospects for multi-sector progress on city sustainability under the NUA. Planning theory & practice, 19 (1), 127–130.

- Horne, R., et al. 2020. From Ballarat to Bangkok: how can cross-sectoral partnerships around the Sustainable Development Goals accelerate urban liveability? Cities & Health Special issue: Transforming city and health: policy, innovation and practice.

- International Institute for Sustainable Development. Available from: https://www.iisd.org/.

- International Institute for Sustainable Development. Peg - a community indicator system for Winnipeg. Available from: https://www.iisd.org/project/peg [Accessed 3 December 2019].

- Lowe, M., et al. 2015. Planning healthy, liveable and sustainable cities: how can indicators inform policy? Urban policy and research, 33 (2), 131–144. doi:10.1080/08111146.2014.1002606.

- Parise, I., 2018. A brief review of global climate change and the public health consequences. Australian journal for general practitioners, 47 (7), 451–456. doi:10.31128/AJGP-11-17-4412.

- Sachs, J.D., et al., 2019. Six transformations to achieve the sustainable development goals. Nature sustainability, 2 (9), 805–814. doi:10.1038/s41893-019-0352-9.

- Steffen, W., et al. 2018. Deluge and drought: Australia’s water security in a changing climate. Climate Council of Australia.

- UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs - Population Division. World urbanization prospects: The 2018 revision. 2018. New York.

- UN Global Compact Cities Programme, 2017. Bangkok in Melbourne: the BMA urban liveability and resilience program. Melbourne: RMIT University.

- United Nations, United nations sustainable development blog [Internet]. Available from: http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/ [Accessed 2 August 2017].

- United Nations Development Programme, 2015. United nations sustainable development goal 11: making cities inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable. Available from: http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/cities/.

- United Nations Sustainable Development Goals: 17 goals to transform our world. 2015.

- World Health Organization. Healthy cities. Available from: https://www.who.int/healthpromotion/healthy-cities/en/ [Accessed 14 January 2020].

- World Health Organization, 2016. Shanghai declaration on promoting health in the 2030 Agenda for sustainable development. 9th Global Conference on Health Promotion, 21-24 November 2016. Shanghai: World Health Organization.