SUPPORTING CITY KNOW-HOW

Human health and planetary health are influenced by city lifestyles, city leadership, and city development. For both, worrying trends have lead to increasing concern, and it is imperative that these become core foci for urban policy. This will require concerted action; the journal Cities & Health is dedicated to supporting the flow of knowledge, in all directions, to help make this happen. We wish to foster communication between researchers, practitioners, policy-makers, communities, and decision-makers in cities. This is the purpose of the City Know-how section of the journal. We, and our knowledge partners, the International Society for Urban Health and Salus.Global invite you to join these conversations with the authors and communities directly, and also, we hope, by publishing in Cities & Health.

This thematic issue of Cities & Health focusses broadly on mainstreaming health in urban design and spatial planning. In all it comprises a leading editorial and 15 articles. Together these provide insight into various aspects of spatial planning, design and governance for urban health and health equity.

Shorter pieces include commentary and debate, book reviews and a think-piece.

We invite you to scan this wealth of content, as there are many shared urban problems, and shared solutions waiting to be discovered.

The eight research papers and their findings are distilled in this paper as accessible ‘City Know-how’ briefings to support urban place-based research, policy and action.

As a journal, we welcome conjecture, commentary and debate arising from these papers. Let’s make human settlements healthier and more equitable for communities, and healthier for the planet.

Healthy urbanism framework redefines healthy urban development

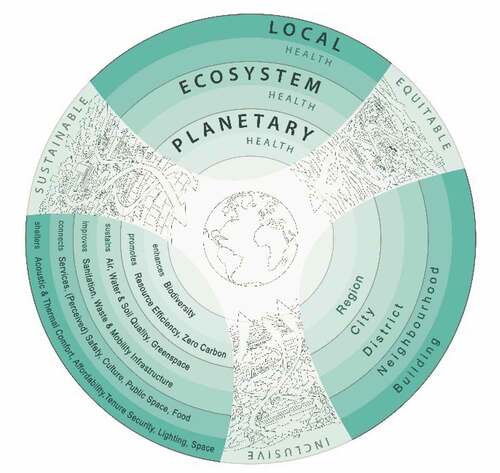

The THRIVES conceptual framework.

New healthy urbanism framework reverses traditional focus on individual lifestyles, focusing on equity, inclusion and sustainability as essential components for urban health.

For the attention of: Those involved with teaching and practicing urban planning, architecture, urban design, engineering, transport and public health.

The problem: The idea of ‘healthy’ urban development has been narrowly framed, resulting in poor understanding of how to create places that support health and wellbeing. Health inequities have been perpetuated by a focus on individual ‘lifestyle choices’, such active travel and nutrition, which downplay the role of structural barriers to healthy living. Similarly, environmental sustainability has often been left out of public health messaging for place-making, rather than framed as an immediate imperative for human health. A new model is needed to communicate and align action for healthy urbanism.

What we did and why: We produced a new conceptual framework called THRIVES (Towards Healthy Urbanism: Inclusive, Equitable, Sustainable) that bridges social and environmental concerns to redefine healthy urban development. The framework argues for a renewed focus in built environment research and practice on the links between human, ecosystem and planetary health, that must be underpinned by the principles of equity, inclusion and sustainability. We used participatory methods to create this framework, learning from built environment and public health professionals.

Our approach adds:

An integrative conceptual framework explaining how urban policy and design affect health at multiple spatial and temporal scales

Repositioning planetary and ecosystem health as central concerns for supporting human health in cities

Refocusing attention on structural barriers rather than individual ‘lifestyle’ choices, necessitating inclusive processes that work for equitable outcomes

An open source and adaptable visual framework for healthy urban development produced through participatory methods.

Implications for city policy and practice: Participants in our workshop viewed the THRIVES framework as a lens to examine healthy urban development. It could be used to achieve the following:

Inform the scope and contents of impact assessment (health, environmental and strategic environmental),

Assess the potential for promoting health through spatial planning or design projects,

Support participatory design and planning by providing a shared understanding of how projects will impact health for future residents and affected populations.

Further information on the framework, including case studies and a free online short course can be found here at: healthyurbanism.net

Full research articles: Towards Healthy Urbanism: Inclusive, Equitable and Sustainable (THRIVES): An urban design and planning framework from theory to praxis by Helen Pineo (@helenpineo).

Incorporating practitioner knowledge to test and improve a new conceptual framework for healthy urban design and planning by Helen Pineo (@helenpineo), Gemma Moore (@mooregemma) and Isobel Braithwaite (@izzybraithwaite).

Solutions to integrate health objectives into new urban development

The ‘Grow Community’, Bainbridge Island, Washington, USA. Credit: Helen Pineo.

New research explores how design team professionals manage developers’ risks to integrate health into new urban development.

For the attention of: Professionals working on new development (e.g. architects, sustainability consultants, engineers, urban designers, etc.) planners and public health teams.

The problem: The design of built spaces affects health. Research has focused primarily on healthy planning policy development rather than implementation in the process of urban development. There is a knowledge gap about the specific problems encountered by design teams when they seek to create healthy buildings and places, including the solutions that they have adopted to overcome such challenges.

What we did and why: To explore professionals’ experiences of creating healthy development projects, we interviewed 31 built environment and public health practitioners in six countries (Australia, China, England, Netherlands, Sweden and the USA). We asked participants to tell us about a project in which they had tried to integrate health and wellbeing design measures, talking us through the background, motivation, people involved, challenges they encountered and opportunities to overcome those.

What our study adds: Using the participants’ descriptions, we classified developers into two general categories about their willingness to design for health.

We found three key themes that related to integrating health into new buildings and communities. Managing risk, responsibility and economic constraints were paramount to persuade developers to adopt healthy design measures. Participants could push business-as-usual practices towards healthy urbanism by showing economic benefits or piloting new approaches. Finally, building knowledge and capacity across professionals and the public will support healthier development.

Implications for city policy and practice: There are important lessons for urban design teams, policy-makers and practitioners.

Design team professionals should understand and manage developers’ risks to integrate health into new urban development. To do so, they need to match developers’ needs with evidence about the health and financial benefits that are created through specific design measures.

Policy-makers should consider the full range of incentives for healthy development, including land ownership transfer and the potential for collaborative action.

Practitioners may benefit from further support through knowledge sharing networks and training for inclusive design process.

Additional information and resources at healthyurbanism.net

Full research article: Built environment stakeholders’ experiences of implementing healthy urban development: an exploratory study by Helen Pineo (@helenpineo) and Gemma Moore.

From data to policies: let the data speak to make local policies more informed about health and social inequalities in health

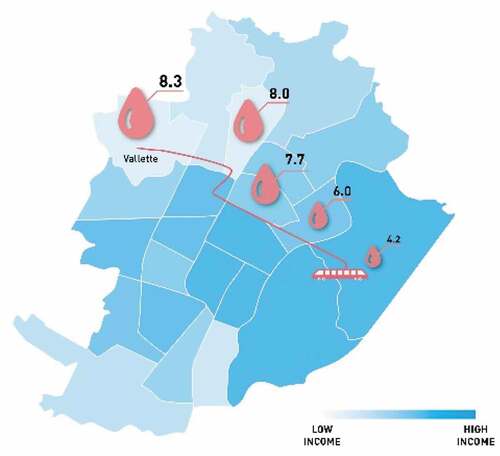

Prevalence of type 2 diabetes, according to the place of residence in the city of Turin (2017). The different shades of blue represent the level of income of the neighbourhoods (average family income). Age-adjusted prevalence of diabetes is two times higher in Vallette (8.3%) than in the wealthiest city neighbourhood (4.2%).

From data to policies: let the data speak! Making local policies more evidence-informed about health and health inequalities. Developing a community engagement toolkit to address health inequalities in urban settings.

For the attention of: Policy makers and Stakeholders (Local and Municipal Authorities, decision-makers from governmental and private institutions, civil society organization) in the fields of health, social service, education, workplace, urbanism, immigration, environmental issues, and local community.

The problem: Since the evidence policy gap often prevents policymakers from using the evidence provided by experts, appropriate structures and mechanisms of governance are needed to overcome this barrier.

What we did and why: Starting from epidemiology evidence, a community of experts, policymakers and stakeholders was engaged in a participatory evidence-based decision-making process using the research-action approach and several stakeholder engagement strategies to raise awareness and foster intersectoral actions aimed at tackling social health inequalities. More than 50 stakeholders and high-profile local policymakers were involved in a co-investigation, co-decision and co-creation processes to reduce social health inequalities in the city of Turin.

What our study adds: The study demonstrate that the ‘equity lens’ are an effective criterion to identify potential health gains as achievable targets for policymaking, a useful metric for comparative analysis of the impact of different policies and a mean to foster stakeholder’ attitude to cooperate in a multi-sectoral approach.

Implications for city policy and practice: The city is considered an ‘umbrella’ setting under which all other settings (school, workplace, local community … etc) converge and may be coordinated to achieve common objectives for health promotion and prevention.

A local, epidemiologic longitudinal infrastructure may provide factual evidence for raising awareness with good storytelling, while facilitating the health inequalities impact assessment and the results/impact evaluation.

A systematic cooperative effort of the action-research approach with stakeholders is needed to ensure effectiveness and participation in innovation.

Other relevant information: Mindmap Cities: MINDMAP aims to identify the opportunities offered by the urban environment for the promotion of mental wellbeing and cognitive function of older individuals in Europe.

Full research article: Focusing urban policies on health equity: the role of evidence in stakeholder engagement in an Italian urban setting by Nicolás Zengarini, Silvia Pilutti, Michele Marra, Alice Scavarda, Morena Stroscia, Roberto Di Monaco, Franca Beccaria & Giuseppe Costa.

Factors that influence urban park access

Image of Druid Hill Park in Baltimore, Maryland, USA. Credit: Daniel Hindman.

Park access is about more than the distance to get there.

For the attention of: Those responsible for managing green public space and parks, city government, directors of parks and recreation and green space advocates.

The problem: Current policy prioritizes time to walk to the park as a measure of access. We sought to investigate a more holistic model of park access that would promote equity.

What we did and why: We designed a survey tool based on a comprehensive theory of access. We then performed door to door administration of the survey in two historically disinvested communities bordering a large park in Baltimore City, MD to determine factors associated with self-reported park use.

What this study adds: We found that whilst time to walk to the park is an important metric, it is insufficient to describe the barriers to park use in urban communities.

We found that park access was associated with perceived safety and programming but not with time to walk to the park.

We also found that those who reported the neighbourhood as less affordable were more likely to use the park.

Implications for city policy and practice: Our finding shows that

Factors that influence perceptions of park safety should be prioritized as essential components of park access.

Activity programming should be considered an essential component of park accessibility, and should be designed and implemented with a focus towards the local community.

Full research article: Beyond proximity and towards equity: a multidimensional view of urban greenspace access by Daniel Hindman, Jessie Chien, Craig Pollack (@cepollack)

An integrative approach to equitable climate resilience

The integrative resilience.

To plan equitable climate interventions in times of systemic crisis cities must be trauma-informed and make healing justice a key feature of urban resilience planning.

For the attention of: Transnational municipal networks such as C40, ICLEI Resilient Cities, UCCRN; Journalistic platforms covering cities (e.g. The Guardian, The Atlantic, Grist, Bloomberg Cities); Media-makers (e.g. How to Save a Planet podcast; OnBeing podcast; Democracy Now; All We Can Save; Heated newsletter).

The problem: Our approach to resilience and vulnerability is narrow and outdated. It barely considers the health implication of climate change on urban populations, and even less so its mental health dimensions. Climate change will likely increase exposure to trauma, so integrating the principles of trauma-informed care and healing justice is urgently needed to design meaningful interventions that foster equitable climate outcomes.

What we did and why: Investigated how ‘official’ narratives and visions of resilience, as found in municipal climate plans, compared to the needs, values, and priorities of populations on the ground – especially vulnerable groups. Convened a public workshop in case study cities to complement document review and key informant interviews with the experiences of frontline groups. Proposed the original concept of ‘integrative resilience’ to stimulate innovation among policy-makers, urban practitioners, and community leaders in transforming the way resilience is planned in cities.

What our study adds:

A new way of thinking about vulnerability, and a more expansive and attuned picture of what it takes to be resilient at a time of rampant climate change;

Introduction of a new definition of resilience that integrates insights from disciplines such as interpersonal neurobiology and public health that add to our understanding of what healthy adaptation could look like on the ground.

Implications for city policy and practice: There need to be deeper understanding of local needs, values and priorities when it comes to defining and operationalizing resilience. This approach provides a blueprint for expanding current focus of climate action plans and municipal interventions, complete with preliminary recommendations for new indicators to assess population health and metrics of success. This model equally applies to systemic crises such as COVID-19.

Full research article: Toward integrative resilience: a healing justice and trauma-informed approach to urban climate planning by Chiara Camponeschi

How a municipality can improve health and wellbeing in the city by using the collective impact model

Jerusalem city centre light rail line. Improving health and wellbeing through improvements in public transportation, accessibility, mobility, business and walkability. Photo: Gal Meiri.

To improve health and wellbeing in cities, municipality employees, urban planners, architects, politicians, citizens, NGOs and funders can benefit by using the collective impact model for working effectively together.

For the attention of: Elected officials (policy makers), funders and urban planners. Citizen committees and municipality employees.

The problem: Achieving health and wellbeing for all citizens is the number one goal of the WHO. This goal is extremely challenging and requires cooperation among many different parts of society including policy makers, funders, NGOs, citizen representatives, and committed public employees. The problem is that these multiple partners are not at the present working cooperatively and have different agendas.

What we did and why: We focused on four of the collective impact model in order to encourage various multicultural, multi-level sectors of the local community groups that don’t usually work cooperatively since they don’t understand each other. Collective impact models or frameworks are approaches supporting networks of community members, organizations, and institutions to advance equity by learning together, aligning, and integrating their actions to achieve population and systems-level change.

Based on collective impact, a communication tool was developed which created a common language to deal with issues of health and wellbeing as well as poverty, climate change, inequality, economic development. This in order to progress with the WHO sustainability goals of health & wellbeing (SDG3).

What our study adds: This study describes a roadmap of how a multicultural city improved health and wellbeing with the following components:

develop a communication tool for cooperative planning and activities

set common agendas across multiple departments, officials and citizens,

create a shared measurement system,

create mutually reinforcing activities,

create backbone support across various sectors of society (political, citizens, public employees).

These steps allow sustainability and enhance achievement of SDG3 (health and wellbeing) as well as other SDGs.

Implications for city policy and practice: Create a team that includes members from various sectors of society and civil service and teach them how to communicate, set goals, use a common language and focus on how to impact and sustain achievements.

‘Collective impact is a marathon, not a sprint’: Funding must be designated for activating and achieving these goals.

For further information: A case study on the use of the SDGs with a Collective Impact Initiative in Southwest Florida: Study showing the use of a Collective Impact approach.

WHO European Healthy Cities Network: WHO Healthy Cities is a global movement working to put health high on the social, economic and political agenda of city governments. For over 30 years the WHO European Healthy Cities Network has brought together some 100 cities and approximately 30 national networks to pursue health and health equity through city-wide approaches.

The Collective Impact Forum: provide resources, host events, and offer coaching for people working to advance equity and achieve systems change using a collective impact approach to collaboration.

Full research article: Health and wellbeing (SDG3) in urban design and spatial planning: A retrospective roadmap towards the Collective Impact Model by Miri Jano Reiss, Amiram Rotem, Ofer Gridinger,Yael Tzur, Gil Reichman, Rakel Berenbaum and Chariklia Tziraki

Reviewing the impact of neighbourhood design on our health and wellbeing

‘Shape our City’.

Our systematic review of the impacts of neighbourhood design on well-being found strong evidence linking design principles such as walkability and access to green space with health and well-being.

For the attention of: Spatial planning and health teams, planners and consultants in public health.

The problem: The design of a neighbourhood plays a central role in shaping the health and well-being of residents. Several studies have investigated the impacts of neighbourhood design on health and well-being. Yet, there are limited reviews investigating the quality of the evidence and the most effective interventions at a population level.

There is a need to present a holistic account of the relationship between urban environment and well-being and identify gaps in the evidence base.

What we did and why: We conducted a systematic review of existing evidence investigating the impact of neighbourhood design on health and well-being. A total of 7694 research articles and published reports were screened to identify studies that matched our aims and objectives. Studies selected for inclusion were subject to a rigorous quality assessment process using the Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies following which 22 studies deemed to be of moderate or high-quality were included in the findings.

What our study adds: Evidence from our review reinforces existing research about the important associations between neighbourhood design and well-being.

There was strong evidence linking walking and cycling infrastructure with increased physical activity and active transport

Poor neighbourhood quality increases the risk of functional loss

The evidence linking neighbourhood green quality and mental health was limited

Our review also identified areas of uncertainty such as associations between proximity to green space and the increased risk of asthma among children.

Implications for city policy and practice: For urban health we found it important to note that promoting health through the design of the neighbourhood can improve wellbeing and quality of life at a population level. However, there is also need for more rigorous empirical studies that will enable the identification of the causal relationships.

Link for further information: The UPSTREAM project

Full research article: Designing Healthier Neighbourhoods: A Systematic Review of the Impact of the Neighbourhood Design on Health and Wellbeing by Janet Ige-Elegbede (Janet_Ige), Paul Pilkington (paulpilkington), Judy Orme, Ben Williams (BurfordBen), Emily Prestwood, Daniel Black (@db_associates) and Laurence Carmichael.