ABSTRACT

Despite rising concern for climate change in cities, urban informal workers are rarely considered in climate and health interventions. Globally, about two billion people work in the ‘informal economy,’ which encompasses all livelihoods lacking legal recognition or social protections. To encourage more holistic studies of workers’ health in urban areas, we discuss recent action-research in Zimbabwe’s cities of Harare (population 2.4m) and Masvingo (urban population 207,000). Using surveys (N=418) and focus group discussions (N=207) with informal urban agriculture workers and plastic waste-pickers, we analysed their climate-related, occupational, and environmental health risks. Approximately 55% of waste-pickers and urban agriculture workers reported that heat extremes already shortened their working times and lowered incomes. We highlight the close links between living and working conditions; discuss gendered differences in risks; and examine how heatwaves, water scarcity, and floods are affecting informal workers. In Masvingo, local authorities have begun collaborating with informal workers to tackle these risks. We recommend multi-sectoral, co-produced strategies that can simultaneously promote health and resilient livelihoods. Although climate change could further entrench urban inequalities, there may also be unusual opportunities to spark action on climate change by using a health lens to improve livelihoods and foster more inclusive, resilient urbanisation pathways.

Introduction

There is growing recognition of climate change’s health impacts in urban areas (Pineo Citation2022, Patz and Siri Citation2021), but far less attention to its complex effects on informal workers’ health and livelihoods. Worldwide, an estimated 2 billion people work in the ‘informal economy’, which encompasses all livelihoods lacking legal recognition or social protections (ILO Citation2018). Due to their unregistered status, informal workers are usually invisible in official data and neglected by health-promoting interventions (Lund et al. Citation2016). At the same time, many informal workers are amongst the 1 billion residents of informal settlements (‘slums’), who often face inadequate shelter and multiple forms of socio-economic exclusions (Ezeh et al. Citation2017, UN-Habitat Citation2022). Such hazardous living and working environments may create a range of threats to their health and well-being (UN-Habitat Citation2022). Climate change is amplifying these risks in cities and contributing to ill-health via more frequent or intense heatwaves, floods, droughts and loss of biodiversity, with residents of informal settlements often recognised as highly vulnerable (Satterthwaite et al. Citation2020, Borg et al. Citation2021, Hambrecht et al. Citation2022). According to the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report on cities, ‘Informal settlements and informal economies [are] not routinely included in formal urban and national monitoring…the innovation, as well as particular concerns and capacities of the informal sector, [are] not always measured’ (Dodman et al. Citation2022, p. 971). As discussed below, there is limited consideration of how climate change is affecting the health of urban informal workers, and these labourers already confront several overlapping domestic and workplace risks. It will be vital to develop multi-faceted responses that can address the climate-related and other health concerns in the informal economy, especially in African cities where informal livelihoods sustain the majority of low-income residents.

This paper explores the climate-related, occupational, and environmental health risks facing informal workers in Zimbabwe, in order to encourage more holistic studies of these workers’ health in urban areas. After a literature review and conceptual framework (Section 2), Sections 3 and 4 will explain our mixed-methods findings from research in the cities of Harare and Masvingo (TARSC et al. Citation2021). The latest available data shows that in 2019, almost 80% of Zimbabwe’s employment was informal (ILO Citation2019), and informal livelihoods and settlements are pervasive in our study sites. Data-collection in both cities focused on informal waste-pickers and urban agriculture workers, alongside workers’ access to water as a cross-cutting theme. In Section 5, we highlight the close links found between living and working conditions, discuss some gendered differences, and examine how climate change is exacerbating informal workers’ challenges. Furthermore, we analyse informal workers’ responses, priorities for change, and emerging collaborations with the local authority in Masvingo. Although our findings are only exploratory, we aim to inform future interventions that can promote informal workers’ health in the face of climate change as well as risks linked to inadequate shelter and precarious work. In Section 6, we offer recommendations and call for further research into how informal workers are affected by and respond to cities’ interrelated climate and health risks.

Literature review and conceptual framework

Informality, health, and climate in African cities

COVID-19 has reinvigorated interest in workplace health, but few studies have focused on occupational health and the informal economy. Recently, occupational health research has highlighted the factors that enable workers’ ability to thrive, while recognising the diverse employment patterns globally (Sorensen et al. Citation2021, Peters et al. Citation2022). However, only a handful of occupational health studies have centred upon informal workers or identified their key role in the ‘future of work’ (Benach et al. Citation2014, Loewenson Citation2021, Schulte et al. Citation2022). Informal workers’ unrecognised status means they are often excluded from routine data-collection systems; their limited collective organisation means their voice and priorities may be side-lined in urban interventions (Tilly Citation2020). Because of their mobile, dispersed, temporary, or hidden workplaces (including in homes and informal settlements) as well as political exclusions and stigmatisation, informal workers are rarely incorporated in municipal plans or healthcare systems (Benavides et al. Citation2022). Below we discuss the limited existing literature on health, informality, and climate change in African cities (including in Zimbabwe), while also identifying some key gaps that we aim to fill in our case study.

Many informal workers are at elevated risk of ill-health due to injuries, exposure to toxic substances, and unsafe working conditions, with additional risks linked to their residence in informal settlements. Although informal labourers are extremely diverse in their demographic profiles and working conditions, they often lack vital services and infrastructure including water, sanitation, and rubbish collection (Benavides et al. Citation2022). These workers typically have lower incomes and more limited training than formal workers, as well as scanty access to healthcare or other social protections (Benavides et al. Citation2022, Lund et al. Citation2016). Informal workers’ health risks are also strongly shaped by gender, migration status (Hargreaves et al. Citation2019), employment relations, and level of precarity (Loewenson Citation2021). Women are usually overrepresented in poorly paid, precarious informal sectors like domestic or home-based work (Loewenson et al. Citation2010, Chen and Carré Citation2020). Meanwhile, informal settlements are heterogeneous but often found in marginal or hazardous locations (e.g. floodplains), and residents’ inadequate living conditions, chronic poverty, and food insecurity are commonly linked to heightened levels of malnutrition and communicable diseases (Ezeh et al. Citation2017). Many residents of informal settlements experience low-quality, overcrowded housing; minimal infrastructure and services; ‘everyday’ risks, small- and large-scale disasters; and political, social, and economic exclusions (Corburn and Riley Citation2016, Satterthwaite et al. Citation2019). During the COVID-19 pandemic, informal workers and residents of informal settlements were disproportionately affected due to their overcrowded and unsanitary living conditions; limited access to PPE and vaccines; and reliance on daily earnings that led many to continue working despite lockdowns (Corburn et al. Citation2020, Tampe Citation2021, Chen et al. Citation2022, Zhanda et al. Citation2022).

Extreme weather events and climate change can negatively affect urban workers’ health and livelihoods via several pathways. Cities are already prone to elevated temperatures because of the ‘urban heat island’, and excessive heat can especially affect those labouring outdoors and in hot workplaces (Levy and Roelofs Citation2019, Ebi et al. Citation2021). Outdoor workers are especially exposed to heatwaves, with significant associated risks to their productivity and health (Moda et al. Citation2019, Habibi et al. Citation2021). Health effects of excessive workplace heat may include reduced productivity, exhaustion, cardiovascular stress, kidney damage, and sometimes death (Nunfam et al. Citation2019, Kjellstrom et al. Citation2016). Globally, heat exposure resulted in a loss of 470 billion potential labour hours in 2021 (Romanello et al. Citation2022). In addition to heatwaves, climate change may promote more intense or frequent extreme weather events (e.g. floods, landslides, and drought); it is also expected to intensify food insecurity and amplify the risk of vector-borne diseases and biological hazards, all of which can affect workers’ health (Schulte et al. Citation2016, Alcayna et al. Citation2022). But to date, few studies of climate and health have analysed the wide-ranging impacts on urban informal workers.Footnote1 Prior reviews of climate, health, and workers’ safety have focused almost entirely on heatwaves (Flouris et al. Citation2018, Ansah et al. Citation2021), and the complex climate-related risks to informal workers’ health thus remain poorly understood, especially in African cities.

There is particularly limited climate research with informal workers in Zimbabwe’s cities, including how climate change will influence an array of pre-existing public and environmental health risks. Climate projections suggest that by 2050, Zimbabwe’s rises in mean annual temperatures may exceed 3°C; precipitation will likely decline overall, alongside ‘increasingly volatile weather events’ (Government of Zimbabwe Citation2021, p. 21). Both floods and droughts in Zimbabwe can ‘increase the spread of water-borne diseases’, and cities in Zimbabwe already face recurrent cholera outbreaks after these weather events (Government of Zimbabwe Citation2021, p. 8). Prior climate research has often focused on Zimbabwe’s rural areas, but there is rising interest in urban climate-related risks and their interaction with low-quality living conditions (Dodman and Mitlin Citation2015). With highly unreliable grid electricity in Harare’s informal settlements, many residents commonly utilise firewood, sawdust, and charcoal as energy sources (Gandidzanwa and Togo Citation2022). Reflecting both rising drought and poor municipal services, there is profound water stress including in our study sites of Masvingo and Harare. Low-income Harare residents often use shallow wells that are vulnerable to contamination, and the burdens of water collection disproportionately affect women and girls (Matamanda et al. Citation2022). Meanwhile, urban agriculture and small livestock-keeping in Harare and Masvingo can promote food security, but when practiced in wetlands, streambanks, or unhygienic conditions in backyards, urban agriculture may only heighten environmental health risks (Mwonzora Citation2022). Urban agriculture in Masvingo is already affected by climate change: heat stress has led to rising illness and mortality amongst livestock, while food spoilage has increased due to rising temperatures and humidity (Chari and Ngcamu Citation2022). These few reports highlight the need for a more systematic analysis of the links between climate change and longstanding environmental, public, and occupational health risks in Zimbabwe’s cities.

Conceptual framework: towards a multi-level analysis of informal livelihoods in a changing climate

Although there is ample attention to climate change and heat stress facing outdoor workers (as noted above), it will be crucial to go beyond sector-specific analyses and consider key cross-cutting determinants of health in the informal economy. Recent studies have recognised the need to analyse the multi-level dynamics of urban informality (Banks et al. Citation2020) and to develop inclusive climate change strategies, which are attuned to African cities’ widespread informality (Cobbinah and Finn Citation2022). Effective climate action in African cities will require both top-down and bottom-up interventions, which can be co-developed with African informal workers and residents of informal settlements (Finn and Cobbinah Citation2023). Building on these insights, below we explain our study’s conceptual framework and methodological entry-points.

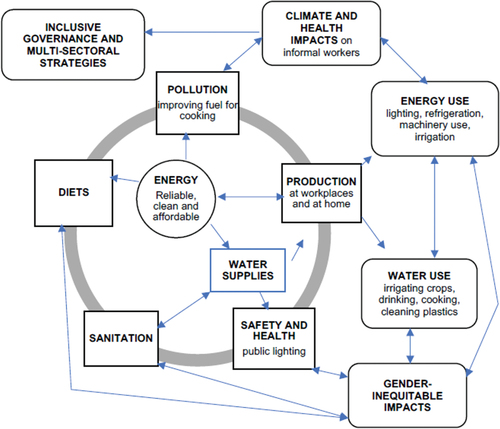

In our related work from India and Zimbabwe, we explored the links between informal workers’ occupational hazards and inadequate shelter, as well as highlighting the role of multi-scalar health determinants like governance, gendered inequalities, and climate change (Dodman et al. Citation2023). We argue that key drivers of informal workers’ health can extend far beyond the workplace (the usual locus of intervention), and it will be vital to analyse these underlying social, environmental, and political factors across scales (Dodman et al. Citation2023, Loewenson Citation2021). Such cross-cutting factors that shape informal workers’ trajectories may include regional or international migration patterns; city planning regulations (and levels of enforcement); and global transformations in the world of work (Breman Citation2020). For instance, informal home-based garment workers have been incorporated into global value chains, but often remain precarious and exposed to multiple hazards linked to low-quality shelter and working conditions (Meagher Citation2016, Chen and Sinha Citation2016). More generally, there is a need for health researchers to analyse informal workers’ housing (e.g. location, quality of provision); access to services and infrastructure; and other built environment factors (TARSC et al. Citation2021; Section 4 below). Affordable, reliable public transport and improved road networks are key concerns for informal workers, especially as floods or other extreme weather events can disrupt their commutes and livelihoods (Ko Ko et al. Citation2020). Furthermore, informal workers’ responses to climate change are strongly shaped by their access to housing and infrastructure, in addition to their social networks, membership in local organisations, and levels of inclusion in urban/national planning (Sections 4, 5 below).

Regarding methodical entry-points, we suggest that qualitative data and participatory action research (PAR) can offer valuable new insights into informal workers’ complex health needs. PAR partnerships have not only analysed informal workers’ health concerns but also co-developed efforts to foster recognition and empowerment, such as initiatives spearheaded by Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing (WIEGO) (Dias and Ogando Citation2015, Lund et al. Citation2016). By using participatory methods with informal workers, researchers can build trust; more fully uncover sensitive topics like stigma or official harassment; and co-create inclusive interventions (Gunn et al. Citation2022). Meanwhile, qualitative research can help to explore lived experiences of risks, the associated knock-on or compounding impacts, and priorities for change amongst heterogeneous informal workers. Although other authors recently argued for disaggregated quantitative data-collection with vulnerable workers (Sorensen et al. Citation2021), it will again be vital to gather qualitative data with informal workers (Boot and Bosma Citation2021). As explained in Section 3, our participatory research in two Zimbabwean cities seeks to motivate additional PAR studies and a more multifaceted understanding of health in the informal economy.

Methods, research questions, and study setting

This research was implemented by the Training and Research Support Centre (TARSC), a non-profit organisation focussed on research and capacity-building for health equity, and two workers’ organisations: Zimbabwe Congress of Trade Unions (ZCTU) and the Zimbabwe Chamber of Informal Economy Associations (ZCIEA). While ZCIEA is a trade union for informal workers, ZCTU promotes labour rights in Zimbabwe more broadly, and the organisations all seek to promote occupational health. The study received technical support from the International Institute of Environment and Development (IIED) in the UK, and it was part of a broader project in Zimbabwe and India with informal workers.

Between 2019 and 2022, the Zimbabwe partners conducted a mixed-methods PAR study to analyse informal workers’ health determinants and how their health outcomes are influenced by a range of public health risks, environmental hazards, and climate change. As part of the project, a detailed report on the Zimbabwe research was published (TARSC et al. Citation2021). We draw on this study and report to answer the following research questions (RQ):

RQ1.

How are climate change and extreme weather events – including floods, heatwaves, and water scarcity – intersecting with other risks to affect informal workers’ health and livelihoods?

RQ2.

What approaches are informal workers using to address these intersecting risks and enhance benefits?

Methods and study setting

The partners collected data with informal workers in Harare, the national capital with a population of 2.4 million, and in Masvingo, which has an urban population of 207,000 (ZIMSTAT Citation2022). Data-collection centred upon 1) informal workers involved in plastic waste collection and recycling; 2) informal urban agriculture workers and food traders (in markets and informal settlements); and 3) water access and quality as a major health issue for both informal residents and workers. To explore an array of intersecting risks (RQ1), we selected informal workers who are in climate-sensitive sectors and face a range of other environmental, public health, and occupational hazards. We also chose these three focus areas because of their pivotal roles in supporting food security, environmental sustainability, and climate resilience for low-income urban residents. Urban agriculture in Zimbabwe is widespread (particularly amongst low-income, food-insecure households), and local authorities may ignore the practice but at other times engage in official harassment (Toriro Citation2019, TARSC et al. Citation2022). Meanwhile, Zimbabwe’s annual plastic waste generation is approximately 300,000 tons (18% of total solid waste), but only 11% is recycled with the rest usually disposed in poorly managed municipal or illegal dumpsites (Gogo Citation2018, Moyo Citation2021). Although Masvingo is more prone to drought and higher temperatures than Harare, we found that climate-related risks are similarly affecting informal workers’ health and livelihoods in both cities (Section 4).

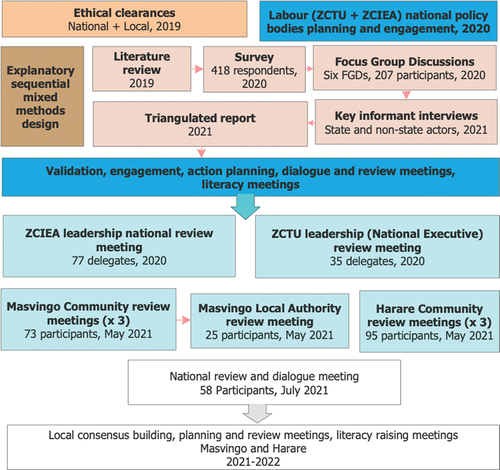

The study sites were purposively selected because of their high concentration of informal workers and informal housing (), and because they had ZCTU and ZCIEA structures with mechanisms to support the action-research process (including in diagnosis, data-collection, and following-up the study’s recommendations). Analysis of RQ2 strongly benefited from our well-established ties with these civil society partners, who utilised the findings to engage with local decisionmakers (Section 5). Sequential mixed-methods were used within a participatory action-research (PAR) study design. This ‘solutions-focused’ approach also fostered synergies between the qualitative stakeholder engagements and quantitative results, helping to inform intervention planning and implementation (). Our methods illustrate the interconnectedness of PAR components, with mixed methods incorporated during all six phases: (i) Problem Diagnosis, (ii) Reconnaissance- data collection and analysis, (iii) Planning based on evidence, (iv) Acting -implementing the plan, (v) Evaluating actions and analysis, and (vi) Monitoring (cf. Ivankova and Wingo Citation2018, p. 11). Below we explain our data-collection methods in greater detail.

Table 1. Study sites.

Literature review

We analysed 71 peer-reviewed and grey literature reports, with a focus on informal employment, occupational health, and climate change in Zimbabwe. We searched for English-language studies published after 2000 in databases including PubMed, EQUINET, and Google Scholar, complemented by a search of grey literature. Key terms included ‘solid waste’, ‘informal urban agriculture’, ‘food marketing’, ‘water access’, ‘climate change’ AND ‘Zimbabwe’, ‘Harare’, or ‘Masvingo’. Documents were manually collated and analysed using thematic and content analysis, and we adapted an analytical framework that uses Drivers, Pressures (major concerns), state (major responses/policies), and Impact to analyse the interaction between occupational health and safety, public health, and climate change.

Quantitative methods

A cross-sectional quantitative survey was conducted in 2020 (shortly before the spread of COVID-19) using an interviewer-administered questionnaire that was developed, reviewed and pilot-tested before final use. Interviews lasted on average 45 minutes and were conducted by 16 trained enumerators in Harare and Masvingo. Questions included demographic and household characteristics; occupational profile, risks and hazards; living, working, and community environments; experiences with climate change and extreme weather-related risks; incomes; individual, household and community assets; perceived impacts of extreme weather events on health and work; assets and approaches used in responding to the risks and enhancing benefits; and the inputs from local authorities and other actors. Within each study cluster, we calculated the sample size (total/combined) of informal workers and residents using a 90% confidence level (z = 1.64 and e = 0.1) using the Cochran formula, giving a total target sample of 420 respondents. As seen in below, the high share of women respondents in our sample (70%) reflects women’s predominance in the sectors of urban agriculture, food marketing and vending in Zimbabwe. We employed multi-stage cluster sampling to establish our sample of residents of informal settlements, and we employed random and snowballing techniques for informal sector workers’ sample (see limitations below). We achieved a response rate of 99.5%, obtaining 418 responses from the targeted 420 (TARSC et al. Citation2021). Data coding and entry were completed by four trained personnel, who were supervised by two TARSC researchers. Data cleaning was implemented at each stage of the process.

Table 2. Demographic profile of survey respondents and FGD participants (TARSC et al. Citation2021).

Qualitative methods

After analysing the quantitative data, the Zimbabwe partners identified areas that required detailed follow-up and validation from the same study population (TARSC et al. Citation2021).Footnote2 Six FGDs were held at neutral venues such as community halls, with combined groups of women and men gathered during daytime (N = 207 total participants). FGDs were gender-balanced and included people living with disabilities, older and younger workers, etc. There were at least two facilitators per FGD, and a question guide was developed, piloted before use, and adapted during FGDs to explore emerging issues. Each meeting averaged 90 minutes; a voice recorder was utilised (after participants’ consent was given); and a transcript for each FGD was prepared within two days of the discussions (TARSC et al. Citation2021). To analyse the FGD data, thematic and content analysis was conducted by three people from the institutions that collected the data in Zimbabwe, with the coded qualitative data and quantitative data being exported to SPSS version 25 for final tabulations. Qualitative findings were integrated with those from the survey and published in a consolidated report (TARSC et al. Citation2021). Alongside the FGDs, the Zimbabwe partners carried out nine key informant interviews with state service providers and civil society organisations, which was used in data validation meetings and triangulated the study’s other evidence (). shows the respondents’ demographic profiles.

Ethics and authorship

Permission was obtained from the Medical Research Council of Zimbabwe (MRCZ/A/2467). The secondary analysis of published findings from the Zimbabwe research obtained clearance from the University of Warwick (BSREC REGO-2019-2340). As noted above, TARSC, ZCIEA, and ZCTU led the data-collection and analysis in Zimbabwe. The International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED) in the UK provided technical peer review. All authors contributed to secondary analysis from the findings of the published Zimbabwe work.

Study limitations and intended contributions

Key limitations relate to the study’s primary data-collection methods, such as a lack of randomised sampling and the use of self-reported data on health outcomes. As a result of informal workers’ mobility, it was impossible to create a sampling list in advance of our survey. Our survey fieldwork therefore utilised cluster and snowball sampling, rather than randomised sampling (TARSC et al. Citation2021, TARSC et al. Citation2022). Our survey sample is not representative; findings cannot be considered representative of informal workers in the participating sites. Further, our data-collection relied largely on respondents’ self-reported health outcomes, which may be under-reported and are necessarily tentative. Additional research will be needed to verify the prevalence of such outcomes, which was precluded by time and resource limitations during this project. The Zimbabwe partners sought to reduce the survey’s bias by triangulating with evidence from five knowledgeable local informants in both sites (e.g. community leaders and experienced informal workers). These key informants helped to corroborate the study’s evidence on overall patterns and trends, but further studies will be needed to rigorously validate our findings. Finally, the Zimbabwe fieldwork did not explicitly consider the impacts of future climate change, as future projections were not available for the study areas.

Nevertheless, the fieldwork provided new evidence of informal workers’ experiences and perceptions, including how health risks at the residence and workplace are interacting with extreme weather events. We gathered grassroots priorities for action in two African cities, which have rarely been featured in prior literature on health and climate change. The study also explores how informal workers are already responding and collaborating with municipal actors to address climate-related and other risks. While acknowledging these limitations, we aim to spark further action-research and multifaceted health interventions with urban informal workers in a changing climate.

Findings

Multiple determinants influence informal workers’ health

Informal workers typically lacked access to adequate housing, healthcare, and transport, in addition to using unclean energy sources and inadequate water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) in their homes and workplaces. As seen in , informal food traders in Masvingo often work outside (lacking structures to shield them from extreme weather), and shows that waste-pickers collect plastics in Harare near a dam that is highly polluted and without clean water. show that many workers rely on shallow wells and unimproved latrines (which can contaminate water sources, especially after floods), and their housing is often flimsy and inadequate in the face of floods, heatwaves, and other disasters. Meanwhile, workers’ marginalised social and legal status has contributed to inadequate access to information on their occupational risks, while also increasing their susceptibility to workplace injuries and illnesses (TARSC et al. Citation2021). In our contributions to the literature on climate and health, this section will explore how extreme weather events have influenced longstanding health risks, and we close with a consideration of workers’ responses and emerging partnerships in Masvingo.

Photo 1. Informal food vendors usually lack adequate infrastructure in the face of heat or other weather extremes, such as this vegetable trader in Masvingo. (Source: T. Mazhambe).

Photo 2. Plastic waste pickers in Harare’s informal settlement of Hopley may clean their plastics in a local ‘dam’, which is already highly contaminated (Source: R. Machemedze).

Photo 3. In Hopley, Harare, this semi-protected well is located close to a dwelling and water quality is a key concern. (Source: R. Machemedze).

Photo 4. A low-quality dwelling in Hopley (Source: R. Machemedze).

Working conditions

Many informal agriculture workers travel lengthy distances while facing heat, air pollution, and chemical hazards; women may also be at elevated risk of gender-based violence, especially in remote locations. Lack of protective gear has left urban farmers highly exposed to dust, snakebites, and pesticides. According to an FGD with a female farmer in Masvingo, ‘We use no protective clothing [when spraying agricultural] chemicals, so we breathe them in, and they get in contact with our skin … We have no prior knowledge on the effects of these chemicals on our health’ (quoted in TARSC et al. Citation2021). Additionally, many urban farmers work on lands where they do not have legal ownership (74%), which they typically reach by walking long distances. These remote locations may increase women’s vulnerability to gender-based violence, such as when walking through and working in tall maize fields where their attackers can readily hide (TARSC et al. Citation2021).

Informal waste-pickers typically endure long journeys along busy roads and with elevated exposure to extreme weather, and they work in poorly managed dumpsites. In the survey, respondents identified several hazards from such dumpsites: injuries from sharp objects; contaminated soil, groundwater, and surface water; and exposure to toxic gases, with associated fires and explosions (TARSC et al. Citation2021). Furthermore, FGD respondents noted that there is the risk of slope instability and landslides from denuded vegetation (cf. Gutberlet and Uddin Citation2017, Zolnikov et al. Citation2021). Waste-pickers may also face ergonomic risks from carrying heavy loads on their backs and heads as they walk over long trips. In Harare, waste-pickers reported travelling over 15 km a day to pick waste, often by foot along major roads (78%) (TARSC et al. Citation2021). This heightens their susceptibility to road traffic injuries and exposure to heatwaves or storms. Waste sorting is almost always conducted in the open (95%), further exposing workers to extreme weather, and they have highly inadequate WASH facilities to clean plastics at work.

Living conditions

Informal workers often face significant shortfalls in housing, infrastructure, and services, while improved shelter provision can promote livelihoods and health in a changing climate. In Harare’s informal settlement of Hopley, there is a major risk of fire outbreaks linked to dense dwellings that are typically made of flammable, low-quality materials (e.g. wood, metal, or plastic) (TARSC et al. Citation2021). These units may collapse after floods or other storms, while also elevating residents’ risk of heat stress in summertime. Additionally, in Harare’s informal settlements, solid waste management is very erratic, with gaps of up to 3 months between collections (TARSC et al. Citation2021). The resulting mosquitos and other pests especially thrive after floods or heatwaves, so that extreme weather exacerbates the risks of vector-borne disease outbreaks. More positively, some waste-pickers who live in Hopley reported taking their plastics home (where they may have better lighting and WASH), rather than sorting their plastics at dumpsites without WASH (TARSC et al. Citation2021). The latter practice underscores the need to analyse informal workers’ assets and responses to risks across multiple sites, with attention to infrastructure at both home and work (see Section 5 for discussion).

Indoor air pollution is linked to unsafe cooking fuels, dust, and smoke at home, with further exposure to air pollutants at outdoor worksites – all of which contribute to respiratory problems. Some residents of informal settlements lack improved fuels for cooking or home-based enterprises, resulting in unsafe alternatives like firewood or even tyres. Accord to a female farmer in Harare, ‘Our air [has] a lot of dust from roads, from the nearby cement factory and smoke from use of firewood, tyres and shoes for cooking. We have informal generator repair shops in residential areas, and [their smoke causes] the air to be dirty’ (quoted in TARSC et al. Citation2021). This array of pollutants from cooking, livelihoods, and roads (amongst other sources) highlights the interrelated risks in informal workers’ living and working conditions; understanding these interconnected challenges can inform holistic strategies to foster health and climate resilience (Section 5).

During FGDs in both cities, participants reported experiencing low-quality WASH and electricity networks (including due to vandalism or poor maintenance), with several deleterious impacts upon health, well-being, and gender equality. For instance, limited energy has negatively affected residents’ diets, food storage, street lighting, safety, and children’s learning opportunities. Some households reduced their intake of foods requiring refrigeration or lengthy cooking times (e.g. beans). Women were especially affected by unclean cooking fuels and other energy sources, much as in other settings (World Health Organisation Citation2016). There are several gender-inequitable impacts of inadequate water and energy access, including women’s time burdens (from queueing for water at early hours) and gender-based violence as women fetch water in areas lacking streetlights. As a male waste-picker in Masvingo explained, ‘Women are not safe. They wake up when it is still dark to go and look for water, and we have no public streetlights. We have had three cases of women who were sexually abused’ (quoted in TARSC et al. Citation2021). The next section explains how these complex threats are affecting informal workers’ self-reported health outcomes and health expenditures.

Injury and illness

In the year before the survey, 26% of women and 28% of men reported experiencing a work-related injury (N = 418). Many injuries result from physical hazards (63% men, 52% women), which largely affect lower limbs and heels (27% men, 36% women), as well as shoulders and hands (30% men, 10% women). As seen in , waste-pickers more frequently reported occupational injuries than those involved in urban agriculture. These self-reported findings are necessarily tentative and will require further research to verify them (as noted in Section 3). Below we continue discussing key findings, with attention to workers’ sector and gender.

Table 3. Occupational injuries by sector and gender (N = 418).

Importantly, injuries can result in substantial missed work times and heavy healthcare burdens, which may exacerbate workers’ precarity. Due to injuries, about two-thirds (66%) of men and almost half (49%) of women reported missing work for an average of 10 days consecutively (TARSC et al. Citation2021). Regarding sector-specific findings, waste-pickers reported injuries to their back, spinal cord and pelvis, chest, abdomen, and head. Injuries amongst urban agriculture workers are relatively rare, but workers noted that they could be fatal, such as from attacks by stray wild animals (TARSC et al. Citation2021). Meanwhile, agriculture workers are mostly affected by environmental hazards like heatwaves (see below), and by prolonged standing, bending, or lifting heavy loads.

While injuries appear more directly related to work hazards, informal workers’ illnesses seem to result from the intersection of hazardous working and living conditions. As seen in , the study found some gendered and sector-specific variations in illnesses (experienced during the 30 days before the survey). Waste-pickers commonly reported diarrhoea, prolonged coughing, and headache; urban agriculture workers often reported headaches and diarrhoea. Waste-pickers’ headaches may partly reflect their dehydration from walking long distances with insufficient water, as noted earlier. The presence of diarrhoea (especially amongst waste-pickers) may reflect the poor access to safe WASH in residences and workplaces. Respiratory problems, coughing, and asthma were again more common amongst waste-pickers (as compared to agriculture workers), which may be linked to a combination of exposures to workplace pollutants as well as from unclean cooking fuels and other sources of air pollution in residential areas.

Table 4. Reported illness by worker group and gender.

As with injuries, these illnesses often result in missed work, ranging from 5 to 22 days, and in costly medical expenses, especially for asthma, prolonged cough, and skin rashes ().

Table 5. Impacts of illness.

Access to health services

Although public health clinics were preferred due to lower costs, these facilities usually lacked access to available or affordable medicines. The FGDs found that local public clinics offer good services in HIV/AIDS management, family planning, and child health, but there were concerns with costly consultations and medicine stock-outs (TARSC et al. Citation2021). As in other African cities, clinic staff were often said to be poorly motivated, and people with chronic conditions or mental illnesses inadequately served. According to a male waste-picker in Harare, ‘Clinics are not able to deal with our mental health problems … If they improve [health-worker] salaries or provide community-based counselling services, that could help’ (quoted in TARSC et al. Citation2021). Health clubs can complement clinics and support with health-promoting activities, but the clubs were currently seen as insufficient and with low coverage.

Climate change and interactions with hazardous living and working conditions

We found that heatwaves, water scarcity, flooding, air and water pollution are negatively affecting informal workers’ health and livelihoods (). Over half of waste-pickers (56%) reported that heat extremes already result in shorter working times and lower incomes. For urban farmers, the unavailability of water during heatwaves was a shared concern (76%), but during heatwaves, a slightly higher share of women farmers reported dehydration and headaches than men (59% of female vs. 55% of male waste-pickers). Amongst waste-pickers, water pollution has reportedly limited their access to water for cleaning plastics, but this concern is especially common for women (71% of female vs. 41% of male waste-pickers). Women waste-pickers were also more likely to report challenges due to air pollution (61% of female vs. 48% of male waste-pickers), potentially due to their use of polluting fuels for cooking and also elevated exposures whilst at work. Thus, the research uncovered gender-inequitable burdens of water and air pollution amongst waste-pickers, while women in urban agriculture were especially affected by dehydration and headaches during heatwaves.

Table 6. Perceived climate and environmental threats, including interactions with public and occupational health risks.

During heatwaves, informal workers may face impossible choices, which may lead to heightened health risks and economic precarity. In some instances, these workers may reduce their heat exposure by remaining indoors or else wearing hats, using umbrellas, and staying in the shade (TARSC et al. Citation2021). Some waste-pickers may bring drinking water from home, but this may also increase their loads carried over long distances and thus heighten ergonomic risks (TARSC et al. Citation2021). Other waste-pickers reported waiting to drink water until they are home in the evenings, risking dehydration at work; others may ask for water from nearby homes; still others may stop working altogether during heatwaves (and thereby lose much-needed incomes). According to a male plastic waste-picker in Harare, ‘We know we need to drink more water when it is very hot, but safe water is not easy to get so we end up drinking less and just stay indoors’ (quoted in TARSC et al. Citation2021, p. 20). In Section 5, we discuss the need to tackle these interrelated risks at homes and workplaces in a changing climate.

Informal workers’ assets and approaches in addressing risks and enhancing benefits

Workers’ education, pooled funds, and social networks represent vital assets in responding to risks and enhancing benefits. Waste-pickers used education to identify recyclable plastics and segregate waste effectively; education was also viewed as key to promoting value addition, improving business processes, and enhancing market access (TARSC et al. Citation2021). In urban agriculture, education was similarly considered essential in the face of climate change to improve yields, conserve water, and address other risks (e.g. pests and post-harvest losses). For both worker groups, networking has fostered social capital, mutual support, and sharing of burdens or tools. In Harare, waste-pickers even reported pooling their funds to maintain roads, which helps to transport plastics to market (Section 5 below). Workers also recounted several proactive approaches to enhance livelihoods, such as farmers’ crop diversification and integrated agricultural activities (e.g. to conserve water and generate compost), while waste-pickers have built relationships with plastic waste buyers and added value via plastic up-cycling and beneficiation (). However, these measures were still considered insufficient and will require better coordination and integration across scales. Many FGD respondents highlighted the lack of legal recognition for informal workers, as well as inadequate or poorly enforced laws to support informal workplace safety and health.

Photo 5. Upcycling plastic waste in Masvingo, where plastics are used to make mats and bags (Source: S. Muradzikwa).

As part of this action-research, ZCIEA and ZCTU (two co-authors of this paper) established ‘champion teams’ with local volunteers in Harare and Masvingo, who are helping to generate inclusive solutions (). These champions are currently raising informal workers’ awareness of climate change and health risks. Masvingo’s local authority signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) in July 2021 with ZCIEA, which has helped enhance information flows and co-develop solutions to identified risks (Kadungure and Sverdlik Citation2021). Following the MoU, Masvingo’s champions team has monitored key risks at the home and workplace: findings are shared every two months with local officials, who are now incorporating grassroots data on workers’ health and priorities in local planning. Future initiatives in Masvingo to promote health and climate-resilient livelihoods being discussed include 1) using organic waste from a market to produce biogas (for use by food traders), and 2) generating organic fertilizer for urban farmers via a community waste segregation pilot, linked to composting organic waste (Kadungure and Sverdlik Citation2021).

Photo 6. Community meeting in Masvingo on findings and follow-up actions to the research (Source: W. Malaya).

Discussion

We found that informal workers can face several threats at the nexus of poor shelter and occupational hazards, while key cross-cutting drivers of risk may include climate change, exclusionary governance, and gendered inequalities. Epitomising the interrelated risks across scales and sites, Harare’s air pollution was linked to the use of unclean household cooking fuels and neighbourhood-level emissions, alongside occupational exposures like burnt waste at dumpsites (TARSC et al. Citation2021). We also uncovered the gender-inequitable impacts of deficient WASH and energy provision at home and work (discussed below). More fundamentally, the challenges facing these informal workers are often rooted in exclusionary governance, as reflected in scanty official efforts to improve living conditions or livelihoods. According to a male recycler in Harare, ‘We are looked down upon; we are considered as non-residents of Harare … We make our own roads for our vehicles to have better access, using our own resources’ (quoted in TARSC et al. Citation2021). Waste-pickers thus can face stigma and entrenched marginalisation as ‘non-residents of Harare’, signalling the social, economic, and political exclusions facing some informal workers. We also found that informal workers are taking various individual and collective steps to address their challenges, and there are emerging inclusive partnerships with local authorities in Masvingo. Finally, the complex linkages found between health risks in living and working conditions, as argued below, can motivate more holistic measures that can foster workers’ health and climate resilience.

Shortfalls in WASH and energy may disproportionately affect women, perhaps because of the gender-inequitable burdens linked to their reproductive roles (e.g. cooking and cleaning), precarious informal livelihoods, and the intersecting health risks from air and water pollution (cf. Ingram and Hamilton Citation2014, World Health Organisation Citation2016). The FGDs uncovered the gender-inequitable impacts of inadequate energy and WASH: in both cities, women reportedly face elevated risks of sexual assault when they collect water in early morning, especially in areas with inadequate public lighting (TARSC et al. Citation2021). Limited public electricity and inadequate WASH are already known to contribute to gender-based violence in insecure urban areas (Sommer et al. Citation2015), and there may be heightened concerns during drought or water scarcity, when women must travel further or arise even earlier to access water (cf. Matamanda et al. Citation2022). In the survey, women waste-pickers were also more likely to report challenges due to air pollution (61% of female vs. 48% of male waste-pickers), which may reflect their elevated exposures to unclean cooking fuels alongside air pollutants at dumpsites and neighbourhood-level exposures (TARSC et al. Citation2021). Such findings highlight the need for joined-up, gender-sensitive strategies to tackle multiple risks, including in the face of climate change.Footnote3

Indeed, our case study has not only illustrated the interactions between climate-related risks, inadequate shelter, and occupational hazards, but it also suggests the wider potential impact of multifaceted interventions. We have underscored the interrelated risks at the home and workplace, which can be exacerbated by extreme weather events and may impose gender-inequitable burdens. But by the same token, improving energy and water provision can offer far-reaching co-benefits for workers’ health, gender equality, and resilience to climate change (). It will be crucial to improve WASH both in informal settlements and worksites (e.g. gender-sensitive toilet designs and sufficient water for hydration, especially during heatwaves), which may offer particular benefits for women’s health. More generally, there is a need for interventions with several co-benefits that may promote workers’ health, inclusive urban development, and climate resilience, such as the waste-to-energy projects being considered in Masvingo (see below).

Organisations such as ZCIEA are strengthening informal workers’ mobilisation locally and nationally, helping to enhance their recognition amongst government officials, and the study’s PAR has already encouraged more inclusive interventions. A signed MoU between ZCIEA and the City of Masvingo provided a vehicle for structured engagement and co-produced solutions between the local authority and informal workers. Experiences in Masvingo illustrate the advantages of collaborative platforms between informal workers and the local authority, which can foster inclusive governance and well-being (Kadungure and Sverdlik Citation2021). But with limited funding and multiple competing priorities, it remains a challenge to implement proposed solutions to tackle climate change and health (e.g. waste-to-energy projects envisioned in Masvingo). There is a related need to develop longer-term strategies, such as incorporating informal workers in municipal or national climate plans, as well as to develop strategies that can scale-up effectively.

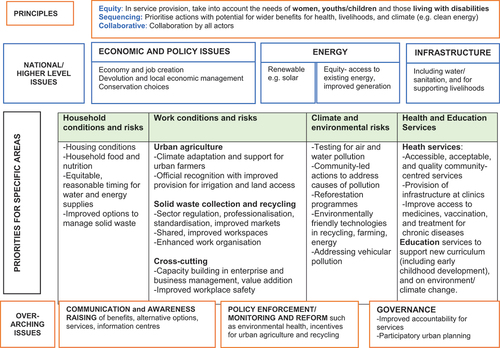

Responses will need to extend beyond top-down formalisation strategies to support workers’ rights and address their priorities. Currently, the Government of Zimbabwe is convening consultations on the formalisation of the informal economy, with the Ministry of Public Service, Labour and Social Welfare in partnership with UNDP and ILO holding stakeholder consultative meetings in 2022 (Ministry of Public Service, Labour & Social Welfare Citation2022). The benefits of and methods for formalisation are widely debated; in the Zimbabwe context, key proposed measures include registration, taxation, organisation and representation, legal and social protection, and business incentives and support, which may offer some helpful entry-points for change (Labour and Economic Development Research Institute of Zimbabwe LEDRIZ and FES Citation2015). But in this study, informal workers themselves identified additional principles of equity, collaboration, appropriate sequencing, and a rights-based approach to help achieve multiple benefits (). Such gains will also require informal workers to be legally recognised, incorporated in local investments, and effective participants in urban decision-making processes affecting their health – including on shelter, environment and health policies, and plans for a just transition in the face of climate change.

There is also a clear need to strengthen people-centred health systems and tailored health-promotion strategies to address informal workers’ complex needs. Although public health clinics are present in both cities, respondents noted several challenges including low quality, insufficiently comprehensive, and costly services (TARSC et al. Citation2021). Informal workers should be included in plans for Universal Health Coverage, and there is a need for enhanced disease and risk surveillance and public health prevention outreach to cover both informal workplaces and informal settlements. Zimbabwe’s health clubs are vital community assets that could benefit from broader coverage areas, and they could be key sites for social dialogue, enhanced information flow, and capacities to address climate change.

Figure 3. Priorities for responses as identified by informal workers.

Conclusions

The informal economy provides livelihoods to most city-dwellers in the Global South but prior research into urban informality and health has typically focused on informal settlements, rather than informal livelihoods (Corburn and Riley Citation2016, Lilford et al. Citation2017). We offer new insights into how climate change is interacting with other health challenges that face informal workers in Zimbabwean cities; we also underscore the close linkages between living and working conditions jointly shaping these workers’ health and livelihoods. A multi-sectoral approach is needed to address such interconnected issues and develop interventions to achieve several benefits, including efforts to expand informal workers’ access to WASH and clean energy at homes and work (Agarwal et al. Citation2022, also below). It will be vital to recognise the capacities and creative responses already present in the informal economy, alongside developing strategies that can foster the inclusion of vulnerable workers. Below we conclude with other recommendations for future research and urban health interventions, which will need to better reflect the multiple, often interrelated determinants of informal workers’ health in a changing climate.

Moving forward, we suggest that participatory, mixed-methods research can deepen understanding of urban informal workers’ health outcomes and priorities in the face of several risks. Studies can explore a wider range of climate-related impacts upon informal workers’ health outcomes (cf. Schulte et al. Citation2022), including the links between climate change and chronic disease or mental illness, and any changes over time. Researchers can incorporate mixed-methods insights into informal workers’ risks across their households, communities, and work processes (e.g. using GIS data, temperature monitoring, and their risk perceptions). We underscored the particular importance of qualitative research, including to explore workers’ lived experiences and the relations between several interrelated threats across scales (Section 3). Future research can also continue analysing how climate change will influence urban food systems, with attention to informal vendors and agriculture workers in African cities (Blekking et al. Citation2022). We explained how inadequate WASH, energy, and precarious livelihoods can impose gender-inequitable burdens, and further studies can incorporate an intersectional lens (e.g. with consideration of disability, migration status, and other overlapping differences). PAR approaches can be especially valuable in helping to engage informal workers and co-develop interventions, as discussed above.

It will be crucial to generate co-produced occupational health and climate interventions with informal workers, including to address heat, floods, and water scarcity as well as their intersections with workers’ longstanding occupational and public health concerns. Grassroots organisations can help to mobilise informal workers to enhance their living and working conditions, with further potential benefits for resilience such as via climate-sensitive slum upgrading programmes (Collado and Wang Citation2020). At the same time, inclusive urban governance will be essential to advance participatory urban planning strategies and improve informal workers’ access to social protection (Dodman et al. Citation2023). Municipal climate plans can help to tackle air pollution, workplace and shelter-related risks, and other environmental health concerns while also promoting health equity. Such joined-up initiatives can potentially foster significant gains for informal livelihoods, gender equality, responses to climate change, and urban health equity (as discussed above). Above all, there is a need to integrate socio-economic, technological, and nature-based climate strategies in cities with inclusive policy interventions to foster multiple co-benefits (cf. Lin et al. Citation2021), especially for informal workers who face several overlapping health challenges. Although climate change could further entrench urban health inequalities, it can also present an opportunity to improve livelihoods, promote health, and foster more inclusive urban development pathways.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Oyinlola Oyebode, Christy Braham, Richard Lilford, David Satterthwaite, and David Dodman for their helpful comments and support with the research. We also express our profound appreciation for the workers, residents and local authorities who were involved in the Zimbabwe study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Artwell Kadungure

Artwell Kadungure is a programme officer at Training and Research Support Centre (TARSC) in Harare.

Rangarirai Machemedze

Rangarirai Machemedze is a research consultant at TARSC.

Wisborn Malaya

Wisborn Malaya is secretary general at Zimbabwe Chamber of Informal Economy Associations (ZCIEA)

Nathan Banda

Nathan Banda is safety and health director at Zimbabwe Congress of Trade Unions (ZCTU).

Rene Loewenson

Rene Loewenson is Director of TARSC.

Alice Sverdlik

Alice Sverdlik is a lecturer in social development at the University of Manchester.

Notes

1. In a key exception, research in Accra and Tamale (Ghana) recently explored how informal workers are affected by floods and heatwaves, including disruptions in infrastructure, livelihoods, and healthcare provision (Gough et al. Citation2019, Codjoe et al. Citation2020).

2. FGD participants’ profile was selected to match that of the survey respondents with regards to key demographic features, albeit not with direct sampling from the survey respondents. Most FGD respondents (70%) were aligned to the sex, age and level of education shares in the survey respondents and the remaining 30% were adjusted for outliers in relation to sex, age, level of education and marital status (TARSC et al. Citation2021).

3. Other findings similarly indicate that women in Zimbabwe are disproportionately burdened with water collection: women in both urban and rural areas perform between 73 and 83% of household water collection roles (ZIMSTAT & UNICEF, Citation2019). Moreover, for a recent review exploring the links between climate change, gender inequalities, and urban water insecurity, see Tandon et al. (Citation2022).

References

- Agarwal, S., et al., 2022. Prioritising action on health and climate resilience for informal workers. London: IIED. Available from: https://pubs.iied.org/21036iied

- Alcayna, T., et al., 2022. Climate-sensitive disease outbreaks in the aftermath of extreme climatic events: a scoping review. One earth, 5 (4), 336–350. doi:10.1016/j.oneear.2022.03.011.

- Ansah, E.W., et al., 2021. Climate change, health and safety of workers in developing economies: a scoping review. The journal of climate change and health, 3, 100034. doi:10.1016/j.joclim.2021.100034.

- Banks, N., Lombard, M., and Mitlin, D., 2020. Urban informality as a site of critical analysis. The journal of development studies, 56 (2), 223–238. doi:10.1080/00220388.2019.1577384.

- Benach, J. et al., 2014. Precarious employment: understanding an emerging social determinant of health. Annual review of public health, 35 (1), 229–253. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182500.

- Benavides, F.G., Silva-Peñaherrera, M., and Vives, A., 2022. Informal employment, precariousness, and decent work: from research to preventive action. Scandinavian journal of work, environment & health, 48 (3), 169–172. doi:10.5271/sjweh.4024.

- Blekking, J., et al., 2022. The impacts of climate change and urbanization on food retailers in urban sub-saharan Africa. Current opinion in environmental sustainability, 55, 101169. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2022.101169.

- Boot, C.R. and Bosma, A.R., 2021. How qualitative studies can strengthen occupational health research. Scandinavian journal of work, environment & health, 47 (2), 91. doi:10.5271/sjweh.3943.

- Borg, F.H., et al., 2021. Climate change and health in urban informal settlements in low-and middle-income countries–a scoping review of health impacts and adaptation strategies. Global health action, 14 (1), 1908064. doi:10.1080/16549716.2021.1908064.

- Breman, J., 2020. Informality: the bane of the labouring poor under globalized capitalism. In: M. Chen and F. Carré, eds. Informal economy revisited: examining the past, envisioning the future. Routledge, 30–37. doi:10.4324/9780429200724-3.

- Chari, F. and Ngcamu, B.S., 2022. Climate change-related hazards and livestock industry performance in (Peri-) urban areas: a case of the city of Masvingo, Zimbabwe. Climate, 10 (12), 187. doi:10.3390/cli10120187.

- Chen, M.A., et al., 2022. Covid‐19 and informal work: evidence from 11 cities. International labour review, 161 (1), 29–58. doi:10.1111/ilr.12221.

- Chen, M. and Carré, F., 2020. Introduction. In: M. Chen and F. Carré, eds. The informal economy revisited: examining the past, envisioning the future. Taylor & Francis, 1–27. doi:10.4324/9780429200724-1.

- Chen, M.A. and Sinha, S., 2016. Home-based workers and cities. Environment and urbanization, 28 (2), 343–358. doi:10.1177/0956247816649865.

- Cobbinah, P.B. and Finn, B.M., 2022. Planning and climate change in African cities: informal urbanization and ‘just’ urban transformations. Journal of planning literature, 38 (3), 361–379. doi:10.1177/08854122221128762.

- Codjoe, S.N., et al., 2020. Impact of extreme weather conditions on healthcare provision in urban Ghana. Social science & medicine, 258, 113072. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113072.

- Collado, J.R.N. and Wang, H.H., 2020. Slum upgrading and climate change adaptation and mitigation: lessons from Latin America. Cities, 104, 102791. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2020.102791.

- Corburn, J., et al., 2020. Slum health: arresting COVID-19 and improving well-being in urban informal settlements. Journal of urban health, 97 (3), 348–357. doi:10.1007/s11524-020-00438-6.

- Corburn, J. and Riley, L., eds., 2016. Slum health: from the cell to the street. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Dias, S.M. and Ogando, A.C., 2015. Rethinking gender and waste: exploratory findings from participatory action research in Brazil. Work organisation, labour and globalisation, 9 (2), 51–63. doi:10.13169/workorgalaboglob.9.2.0051.

- Dodman, D., et al., 2022. Cities, settlements and key infrastructure. In: H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, and B. Rama, eds. Climate change 2022: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. Contribution of working group II to the sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press, 907–1040. doi:10.1017/9781009325844.008.

- Dodman, D., et al., 2023. Climate change and informal workers: towards an agenda for research and practice. Urban climate, 48, 101401. doi:10.1016/j.uclim.2022.101401.

- Dodman, D. and Mitlin, D., 2015. The national and local politics of climate change adaptation in Zimbabwe. Climate and development, 7 (3), 223–234. doi:10.1080/17565529.2014.934777.

- Ebi, K.L., et al., 2021. Hot weather and heat extremes: health risks. The lancet, 398 (10301), 698–708. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01208-3.

- Ezeh, A., et al., 2017. The history, geography, and sociology of slums and the health problems of people who live in slums. The lancet, 389 (10068), 547–558. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31650-6.

- Finn, B.M. and Cobbinah, P.B., 2023. African urbanisation at the confluence of informality and climate change. Urban studies, 60 (3), 405–424. doi:10.1177/00420980221098946.

- Flouris, A.D., et al., 2018. Workers’ health and productivity under occupational heat strain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The lancet planetary health, 2 (12), e521–e531. doi:10.1016/S2542-5196(18)30237-7.

- Gandidzanwa, C.P. and Togo, M., 2022. Adaptive responses to water, energy, and food challenges and implications on the environment: an exploratory study of Harare. Sustainability, 14 (16), 10260. doi:10.3390/su141610260.

- Gogo, J., 11 June 2018. Only 11pc of plastic waste recycled in zim: EMA. The Herald. Available from: https://www.herald.co.zw/only-11pc-of-plastic-waste-recycled-in-zim-ema/

- Gough, K., et al., 2019. Vulnerability to extreme weather events in cities: implications for infrastructure and livelihoods. Journal of the British academy, 7 (s2), 155–181.

- Government of Zimbabwe, 2021. Zimbabwe revised nationally determined contribution. UN-FCCC. Available from: https://tinyurl.com/zim21

- Gunn, V., et al., 2022. Initiatives addressing precarious employment and its effects on workers’ health and well-being: a systematic review. International journal of environmental research and public health, 19 (4), 2232. doi:10.3390/ijerph19042232.

- Gutberlet, J. and Uddin, S.M.N., 2017. Household waste and health risks affecting waste pickers and the environment in low-and middle-income countries. International journal of occupational and environmental health, 23 (4), 299–310. doi:10.1080/10773525.2018.1484996.

- Habibi, P., et al., 2021. The impacts of climate change on occupational heat strain in outdoor workers: a systematic review. Urban climate, 36, 100770. doi:10.1016/j.uclim.2021.100770.

- Hambrecht, E., Tolhurst, R., and Whittaker, L., 2022. Climate change and health in informal settlements: a narrative review of the health impacts of extreme weather events. Environment and urbanization, 34 (1), 122–150. doi:10.1177/09562478221083896.

- Hargreaves, S., et al., 2019. Occupational health outcomes among international migrant workers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The lancet global health, 7 (7), e872–e882. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30204-9.

- ILO, 2018. Women and men in the informal economy: a statistical picture. 3rd ed. Geneva, ILO.

- ILO, 2019. Statistics on the informal economy. Geneva: ILO. Available from: https://ilostat.ilo.org/topics/informality/#WG

- Ingram, J. and Hamilton, C., 2014. Planning for climate change: guide—A strategic, values-based approach for urban planners. Nairobi: UN-Habitat. Available from: https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/download-manager-files/Planning%20for%20Climate%20Change.pdf

- Ivankova, N. and Wingo, N., 2018. Applying mixed methods in action research: methodological potentials and advantages. American behavioral scientist, 62 (7), 978–999. doi:10.1177/0002764218772673.

- Kadungure, A. and Sverdlik, A., 2021. Making strides to improve health and climate resilience in Zimbabwe’s cities. IIED. Available from: https://www.iied.org/making-strides-improve-health-climate-resilience-zimbabwes-cities

- Kjellstrom, T. et al., 2016. Heat, human performance, and occupational health: a key issue for the assessment of global climate change impacts. Annual review of public health, 37 (1), 97–112. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032315-021740.

- Ko Ko, T., et al., 2020. Informal workplaces and their comparative effects on the health of street vendors and home-based garment workers in Yangon, Myanmar: a qualitative study. BMC public health, 20 (1), 1–14. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-08624-6.

- Labour and Economic Development Research Institute of Zimbabwe (LEDRIZ) and FES, 2015. Strategies for transitioning the informal economy to formalisation in Zimbabwe. LEDRIZ, Harare. Available from: https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/bueros/simbabwe/13714.pdf

- Levy, B.S. and Roelofs, C., 2019. Impacts of climate change on workers’ health and safety. In: Oxford research encyclopaedia of global public health. Oxford University Press, 1–15.

- Lilford, R.J. et al., 2017. Improving the health and welfare of people who live in slums. The lancet, 389 (10068), 559–570. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31848-7.

- Lin, B.B., et al., 2021. Integrating solutions to adapt cities for climate change. The lancet planetary health, 5 (7), e479–e486. doi:10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00135-2.

- Loewenson, R., 2021. Rethinking the paradigm and practice of occupational health in a world without decent work: a perspective from east and southern Africa. New solutions: a journal of environmental & occupational health policy, 31 (2), 107–112. doi:10.1177/10482911211017106.

- Loewenson, R., Nolen, L.B., and Wamala, S., 2010. Review article: globalisation and women’s health in sub-Saharan Africa: would paying attention to women’s occupational roles improve nutritional outcomes? Scandinavian journal of public health, 38 (4_suppl), 6–17. doi:10.1177/1403494809358276.

- Lund, F., Alfers, L., and Santana, V., 2016. Towards an inclusive occupational health and safety for informal workers. New solutions: A journal of environmental & occupational health policy, 26 (2), 190–207. doi:10.1177/1048291116652177.

- Matamanda, A.R., Mphambukeli, T.N., and Chirisa, I., 2022. Exploring water-gender-health nexus in human settlements in Hopley, Harare. Cities & health, 1–15. doi:10.1080/23748834.2022.2136557.

- Meagher, K., 2016. The scramble for Africans: demography, globalisation and Africa’s informal labour markets. The journal of development studies, 52 (4), 483–497. doi:10.1080/00220388.2015.1126253.

- Ministry of Public Service, Labour & Social Welfare, 2022. Consultations on the formalisation of the informal economy –. MPSLW Online. Available from: https://www.mpslsw.gov.zw/consultations-on-the-formalisation-of-the-informal-economy/

- Moda, H.M., Filho, W.L., and Minhas, A., 2019. Impacts of climate change on outdoor workers and their safety: some research priorities. International journal of environmental research and public health, 16 (18), 3458. doi:10.3390/ijerph16183458.

- Moyo, J., 1, November 2021. A tide of plastic waste threatens Zimbabwe’s environment and key industries. Development and cooperation. Available from: https://www.dandc.eu/en/article/tide-plastic-waste-threatens-zimbabwes-environment-and-key-industries#:~:text=According%20to%20the%20country’s%20Environmental,recycled%20or%20properly%20disposed%20of

- Mwonzora, G., 2022. Local governance and wetlands management: a tale of Harare City in Zimbabwe. Urban forum, 33 (3), 309–328.

- Nunfam, V.F. et al., 2019. The nexus between social impacts and adaptation strategies of workers to occupational heat stress: a conceptual framework. International journal of biometeorology, 63, 1693–1706.

- Patz, J.A. and Siri, J.G., 2021. Toward urban planetary health solutions to climate change and other modern crises. Journal of urban health, 98 (3), 311–314. doi:10.1007/s11524-021-00540-3.

- Peters, S.E. et al., 2022. Work and worker health in the post-pandemic world: a public health perspective. The lancet public health, 7 (2), e188–e194. doi:10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00259-0.

- Pineo, H., 2022. Towards healthy urbanism: inclusive, equitable and sustainable (THRIVES)–an urban design and planning framework from theory to praxis. Cities & health, 6 (5), 974–992.

- Romanello, M., et al., 2022. The 2022 report of the lancet countdown on health and climate change: health at the mercy of fossil fuels. The Lancet. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01540-9.

- Satterthwaite, D., et al., 2020. Building resilience to climate change in informal settlements. One earth, 2 (2), 143–156. doi:10.1016/j.oneear.2020.02.002.

- Satterthwaite, D., Sverdlik, A., and Brown, D., 2019. Revealing and responding to multiple health risks in informal settlements in sub-Saharan African cities. Journal of urban health, 96 (1), 112–122. doi:10.1007/s11524-018-0264-4.

- Schulte, P.A. et al., 2016. Advancing the framework for considering the effects of climate change on worker safety and health. Journal of occupational and environmental hygiene, 13 (11), 847–865. doi:10.1080/15459624.2016.1179388.

- Schulte, P.A., et al., 2022. Occupational safety and health staging framework for decent work. International journal of environmental research and public health, 19 (17), 10842. doi:10.3390/ijerph191710842.

- Sommer, M., et al., 2015. Violence, gender and WASH: spurring action on a complex, under-documented and sensitive topic. Environment and urbanization, 27 (1), 105–116. doi:10.1177/0956247814564528.

- Sorensen, G., et al., 2021. The future of research on work, safety, health and wellbeing: a guiding conceptual framework. Social science & medicine, 269, 113593. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113593.

- Tampe, T., 2021. Potential impacts of COVID-19 in urban slums: addressing challenges to protect the world’s most vulnerable. Cities & health, 5 (sup1), S76–S79. doi:10.1080/23748834.2020.1791443.

- Tandon, I., et al., 2022. Urban water insecurity and its gendered impacts: on the gaps in climate change adaptation and sustainable Development goals. Climate and development, 1–12. doi:10.1080/17565529.2022.2051418.

- TARSC, MoHCC, CFHD, 2022. Promoting healthy urban food systems: report of a scoping assessment in Harare, EQUINET, Harare. Available from: https://www.tarsc.org/publications/documents/UFS%20Final%20assessment%20Rep%20June%202022.pdf

- TARSC, ZCTU, ZCIEA, 2021. Propelling virtuous and breaking vicious cycles: Responding to health and climate risks for informal residents and workers in two areas of Zimbabwe, Report of evidence from a mixed methods study. Zimbabwe: TARSC. Available from: https://www.tarsc.org/publications/documents/ZIMINFO%20SynthesisRep%20March%202021.pdf.

- Tilly, C., 2020. Informal domestic workers, construction workers and the state. In: M. Chen and F. Carré, eds. Informal economy revisited: examining the past, envisioning the future. Routledge, 246–250. doi:10.4324/9780429200724-44.

- Toriro, P., 2019. Urban food production in Harare, Zimbabwe. In: J. Battersby and V. Watson, eds. Urban food systems governance and poverty in African cities. Routledge, 154–166. doi:10.4324/9781315191195-12.

- UN-Habitat, 2022. World cities report: envisaging the future of cities. Nairobi. Available from: https://unhabitat.org/wcr/

- World Health Organisation, 2016. Burning opportunity: clean household energy for health, sustainable development, and wellbeing of women and children. Geneva: WHO. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/20471

- Zhanda, K., et al., 2022. Women in the informal sector amid COVID-19: implications for household peace and economic stability in urban Zimbabwe. Cities & health, 6 (1), 1–14. doi:10.1080/23748834.2021.2019967.

- Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency (ZIMSTAT) and UNICEF, 2019. Zimbabwe multiple indicator cluster survey 2019, survey findings report. Harare: ZIMSTAT and UNICEF. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/zimbabwe/media/2536/file/Zimbabwe%202019%20MICS%20Survey%20Findings%20Report-31012020_English.pdf[unicef.org]

- ZIMSTAT, 2022. Zimbabwe population and housing Census report. Available from: https://www.zimstat.co.zw/wp-content/uploads/Demography/Census/2022_PHC_Report_27012023_Final.pdf

- Zolnikov, T.R., et al., 2021. A systematic review on informal waste picking: occupational hazards and health outcomes. Waste management, 126, 291–308. doi:10.1016/j.wasman.2021.03.006.