ABSTRACT

Rationale/Purpose

This study investigates the challenges of returning to sport after a COVID-19 shutdown of sport from the perspective of community sport clubs (CSCs). We explore the relationship between the challenges CSCs identified and the challenges the nation’s lead sport agency identified; and similarities or differences in the challenges faced by different types of CSCs.

Design/methodology/approach

Concept Mapping (online) with 57 CSCs in Victoria, Australia.

Findings

CSCs identified eight clusters of challenges related to returning to sport after the COVID-19 shutdown (in highest to lowest mean impact rating order): volunteers; club culture; health protocols; membership; finances; facilities; competition; and governance and division of responsibility. Cluster impact ratings differed by club location, competitive season, venue type, club size, and type of sport offered.

Practical implications

The challenges CSCs face returning to sport are more complex and broader than current national guidelines suggest, with previously existing challenges exacerbated and new challenges emerging. Listening to CSCs is essential to understanding the nuances of, and support needed to address the complex context-specific challenges to returning to operations after a COVID-19 shutdown.

Research contribution

Understanding the challenges and how they differ for CSCs as they return to sport.

Introduction

Sport is integral to Australian society. Three million children and 8.4 million adults participate in sporting activities, and 8 million Australians attend live sporting events annually, from a population of 24.8 million (Boston Consulting Group, Citation2017). More than three million adults also participate in sport via non-playing roles such as volunteer coaches and administrators, or supporters (AusPlay, Citation2019). Sport participation contributes to physical, psychological, and emotional wellbeing, and has economic, healthcare, and social capital benefits (Hughes et al., Citation2020).

Australian sport is a “complex ecosystem with more than 75,000 not-for-profit organisations at national, state and local levels at its centre” (Department of Health, Citation2018), providing a network of community sport clubs (CSCs), and competitions (Boston Consulting Group, Citation2017). Australia’s sporting structures and governance reflect its federated system. Generally, each sport has a national governing body, supported by state/territory associations, underpinned by CSCs. Community clubs vary in size, scope, and purpose. They exist primarily to organise and facilitate competition and training, alongside social activities, fundraising, and community outreach. CSCs are usually volunteer-run, not-for-profit member benefit organisations with limited human and financial capacity. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, CSCs regularly experienced ongoing challenges related to volunteer recruitment and retention, infrastructure, compliance, regulation, planning, external relationships (Doherty et al., Citation2014; Parliament of Victoria, Citation2004), and changing local socio-demographics (Mooney & Hickey, Citation2019).

The COVID-19 pandemic dramatically impacted sport in Australia and internationally. Australia’s 70,000 community sport clubs lost an estimated aggregate of $1.6 bn between March and July 2020 due to COVID-19 (Australian Sports Foundation, Citation2020); this excludes the impact on the health and wellbeing of participants, volunteers, and administrators.

The approach adopted in this study is underpinned by Skille’s (Citation2008) acknowledgement that the way CSC representatives “interpret” new phenomena, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, depends on the context-specific circumstances they are experiencing. It is important to listen to the voices of community organisations and individual volunteers to understand their capacity to respond to changing circumstances with meaningful and effective change in day-to-day practice (Skille, Citation2008). Therefore, it is essential that we examine how the COVID-19 pandemic will interact with existing operational challenges and identify new challenges that could emerge in returning to sport, from the perspective of CSCs. Community sport will be important in sustaining health, resilience, and community spirit during and beyond the pandemic crisis. To enable sport governing bodies and public health agencies to strategically allocate resources and support CSCs appropriately, empirical research is needed to identify and understand issues clubs encounter and anticipate in light of COVID-19.

COVID-19 and sport research

Previous research into organised sport and COVID-19 has primarily reviewed or commented on the impacts of the pandemic (e.g. Hughes et al., Citation2020). For example, contributions have reflected on how COVID-19 could change how sport operates (Evans et al., Citation2020; Fullagar, Citation2020; Ludvigsen & Hayton, Citation2020), how the sport sector should prioritise inclusion and diversity in the future (Fitzgerald et al., Citation2020), and how organised sports should be more entrepreneurial and innovative (Clarkson et al., Citation2020). Although limited research has addressed the impacts and challenges facing CSCs, a commentary piece by Doherty et al. (Citation2020), informed by previous evidence-based insights rather than new empirical evidence, highlighted the need to connect key areas of existing knowledge – around assessing and building community club capacity; embracing innovation; and adapting top-down governing body and public health policy directives to suit local club context – with the emerging COVID-19 related challenges now facing community sport clubs.

Whilst previous reviews discuss the impact of COVID-19 on sport at all levels, we need evidence from the perspective of people with the lived experience of interpreting and responding to the COVID-19 pandemic in these environments. A recent Australian study by Elliott et al. (Citation2021) explored the impact of COVID-19 on the participation and retention of youth athletes, primarily from the athlete, parent, and coach perspectives. They identified “4 Rs” to conceptualise the impact of the pandemic on youth sport – “recognising” the emotional struggle, “reconnecting” with family and social networks, “re-engaging” participants and volunteers, and “reimagining” the purpose and meaning of sport.

We explore the broader challenge of re-opening community sport from the perspective of CSC representatives responsible for administering community sport in Australia. We collected data in June 2020 after community sport in Victoria was shut down in March 2020 and expecting to return, with significant restrictions, in July 2020.

Returning to sport in Australia

Sport Australia – The Australian Federal Government’s lead sport agency – released the COVID-19 Return to Sport Toolkit (Toolkit) in May 2020 (Sport Australia, Citation2020). The Toolkit included resources for sporting organisations to manage the staged resumption of sport as COVID restrictions were lifted. It built on the Australian Institute of Sport (AIS) Framework for rebooting sport in a COVID-19 environment (Hughes et al., Citation2020) and the Australian Federal Government’s national principles for resuming sport and recreation activities (Department of Health, Citation2020).

The Toolkit included a comprehensive checklist for medium to large sporting organisations and a simplified checklist for small organisations. The simplified checklist (“the Checklist”) was the key resource for CSCs to plan the return to sport. To interpret the challenges CSCs perceived relative to the support that they received, we compared the CSCs’ responses in our study to the topics covered in the Checklist. We then discuss additional support that could be provided to CSCs to optimise a return to sport.

Although restrictions on sporting activities were lifted for most Australians by July 2020 (individual sport and non-contact training had resumed), Victorians experienced an extended economic (and complete sporting) shutdown that other Australian states were spared, following a surge of COVID-19 cases in July. The high likelihood of periodic community sport shutdowns, as cities, regions, and nations experience spikes in virus transmission, accelerated by the mutation of COVID-19 (e.g. the Delta variant), means that the challenges associated with a staged approach to returning to sport will have enduring relevance.

In light of the importance of CSCs to the Australian sport system, the paucity of empirical data on the impact of COVID-19 on community sport – particularly from the perspective of club representatives – and information from Australia’s lead sport agency to guide a return to sport, this research sought to answer the following questions:

What are the challenges of returning to sport, post a COVID-19 shutdown, from the perspective of community sport clubs?

To what extent do the challenges identified by the sport clubs correspond to the challenges identified by the nation’s lead sport agency?

How similar or different are the challenges that different types of community sport clubs face when returning to sport?

Methods

Study design

Given the lack of sport-related COVID-19 pandemic empirical data, we wanted to understand the challenges facing CSCs, from the perspective of CSC representatives, when returning to operations post a COVID-19 shutdown. We adopted a Concept Mapping (CM) approach, as it is a well-established method for developing conceptual frameworks of previously unexplored and complex topics (van Bon-Martens et al., Citation2014), and is a method that facilitates the active participation of the people and organisations being studied. We used CM to gather and analyse qualitative and quantitative data, enabling opinions of a knowledge source (in this case, CSC representatives) on a topic of interest (return to sport) to be visually depicted (Trochim & McLinden, Citation2017). Concept mapping is a reliable and valid method of representing complex multivariate data in two-dimensional space (Rosas & Kane, Citation2012).

The key steps of CM are preparation (developing the study question and organising participants); brainstorming (participants contribute ideas); statement sorting and rating (participants organise and value each idea); and data analysis (multidimensional scaling to convert qualitative knowledge to quantitative data and visual maps) (Kane & Trochim, Citation2007). We used the Concept Systems groupwisdom™ online platform to collect, analyse, and present the data. Participants received a AU$50 gift card for their time.

Preparation

The focus prompt to generate ideas from study participants was “A challenge that my club faces as we return to operations post COVID-19 is … ”. Study participants were recruited through snowballing initiated by emails to State Sporting Associations (SSAs) and the research team’s professional networks of CSCs. We aimed to recruit 30–50 CSC administrators across multiple sports to optimise the fit between the sorting data visual and the representation (Rosas & Kane, Citation2012). Interested club representatives completed an online expression of interest (EOI) survey identifying the sport their club offered and their age, gender, club role (president/secretary/other), and length of time in their current role. Any CSC administrator in Victoria aged ≥18 years could participate in this study. Eligible EOI participants were invited to participate in the CM via email in June 2020.

Participants provided demographic information when they first entered the online platform. Based on the work of Doherty et al. (Citation2014), we anticipated variations in the impact of the shutdown on different types of CSCs. Therefore, we gathered data from respondents on five variables: competitive season for their sport (winter/summer/year-round); type of sport offered (individual/small team sport (<10 participants per team)/large team sport (≥10 participants per team)); and club venue/facility (indoor/outdoor/indoor and outdoor), location (metro Melbourne/Regional or rural Victoria), and size (<100/100–200/>200 playing members).

Idea brainstorming

Participants brainstormed as many challenges as they could think of to complete the focus prompt. They could access the online platform multiple times, as well as view and search the de-identified contributions of other participants. We requested they keep each response to a single challenge and add as many challenges as they desired. The brainstorming was open for ten days, and email reminders were sent.

Before making the brainstormed challenges available to participants to sort and rate, the research team synthesised and edited the ideas. The aim was to develop a unique, clearly presented set of challenges that encompassed all the relevant participant-generated ideas (Kane & Trochim, Citation2007). The process involved: downloading the participant-generated challenges; splitting compound ideas; removing ideas irrelevant to the study (e.g. solutions or examples of club activities in response to COVID-19); organising ideas around themes, identifying very similar ideas and selecting the most appropriate idea; and editing ideas for clarity and consistency. We preserved the participants’ original voice where possible (Trochim & McLinden, Citation2017) and cross-referenced the final list of challenges against the original participant-generated ideas.

Statement sorting and rating

We invited anyone who completed an EOI and/or contributed to the brainstorming to participate in sorting and rating. The synthesised and edited challenges were presented in a randomised order and participants had 14 days to (1) group the challenges in a way that made sense to them and (2) rate each challenge for the impact on their club and their club’s ability/capacity to overcome it.

Participants were instructed to group the challenges based on perceived similarity and to not group them according to priority or value (e.g. “Hard to Do”) or to group dissimilar statements together (e.g. “Other”). They were informed that people vary on how many groups they create (range 5–20 groups) (Rosas & Kane, Citation2012) and asked to name the groups they created based on the shared meaning of the challenges.

The rating questions used were: “On a scale from 1 (very low impact) to 5 (very high impact), given your experience, how much does this challenge impact your club?” and “On a scale from 1 (very low ability) to 5 (very high ability), given your experience, what is your club’s ability/capacity to overcome this challenge?”. Participants were asked to rate each challenge using the full scales and relative to all challenges on the list.

Data analysis

After we checked the raw data to ensure participants had followed the sorting and rating instructions, contributions from 36 of the 50 participants were retained for further analysis. We used the groupwisdom™ online platform to conduct a standard CM data analysis (Trochim & McLinden, Citation2017), including constructing a similarity matrix from the participant sorting data and using nonparametric multidimensional scaling analysis with a two-dimensional solution. This produced a point map in which each challenge is positioned on the map relative to every other challenge based on how frequently participants grouped the challenges were together. A stress value – indicating the relative quality of a CM study – was generated to assess the “goodness of fit” between the point map and original sorting data from participants (Rosas & Kane, Citation2012). Finally, hierarchical cluster analysis using Ward’s algorithm was applied to partition the point map into non-overlapping clusters in two-dimensional space. The resulting cluster map is a visual representation of how participants perceived relationships between the brainstormed challenges.

To select the number of clusters that best represented the sorted data, we generated cluster maps with 6–12-cluster solutions. We examined the maps, starting at the 12-cluster solution and moving towards the 6-cluster solution, to identify the cluster solution with the most useful distinction between clusters while merging those clusters that seemed to belong together (Kane & Trochim, Citation2007). After agreeing on the cluster map that best represented the data, we reviewed each challenge to determine if it was a good conceptual fit within the cluster or within an adjacent cluster. Where appropriate, we re-drew cluster boundaries to ensure each challenge was incorporated in the cluster with the best conceptual fit (Mannes, Citation1989).

We calculated the mean impact and ability/capacity ratings for each challenge, and for each cluster, based on the rating data from 49 participants. The relationships between the ratings of each challenge are visually displayed on a bi-variate go-zone graph with four quadrants created using the mean all-challenge impact (x-axis) and ability/capacity (y-axis) ratings. We compared the mean impact rating for sub-groups within each cluster using the groupwisdom™ t-test function (incorporating Welch’s t-test and using the number of cluster items as the sample n for cluster comparisons). Sub-group analysis used demographic variables: type of sport (3 variables); club location (2); club size (3); the season of operation (3); and venue type (3).

Results

Participant demographics, club characteristics, and CM engagement

Fifty-seven CSC representatives representing 23 sports contributed CM data. One participant represented each CSC. See for participant demographics and club characteristics.

Table 1. Characteristics of participants and the CSCs they represented.

Participants brainstormed 173 challenges which the research team synthesised to 68 unique challenges for sorting and rating (). Thirty-six participants sorted the challenges into groups and 49 participants rated the challenges for impact and ability/capacity. Thirty-four participants contributed data in all phases, while seven contributed only to brainstorming.

Table 2. Challenges facing CSCs as they return to operations post-COVID-19 shutdown (by cluster and in order of mean impact rating).

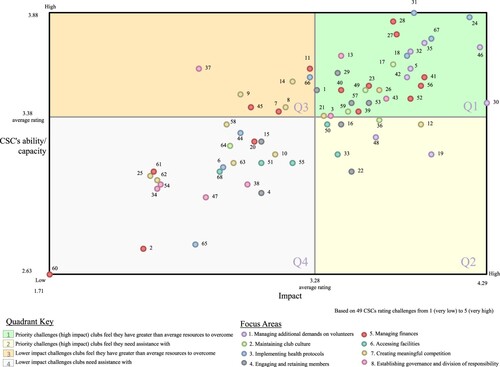

Go-zone graph

is a scatterplot of the 68 challenges plotted using mean impact (3.28 out of 5) and ability/capacity ratings (3.38), commonly referred to in CM studies as a “go-zone”. The 38 challenges located in Q1 and Q2 were above the all-statement mean impact rating and could be considered priorities for support. The 38 challenges in Q1 and Q3 were rated above the all-statement average for ability/capacity, suggesting clubs need less support to address them. To interpret the go-zone, see for the mean impact and ability/capacity ratings for each challenge.

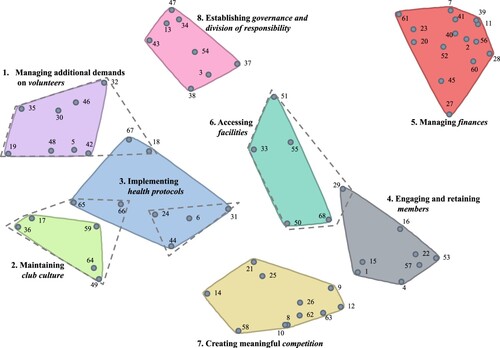

Clusters

The distance between points on the cluster map () is a proxy indicator of the similarity in meaning of challenges. For example, at least 21 participants sorted challenge #39 with every other challenge in Cluster 5 so #39 is located close to these challenges on the map. By contrast, no participants sorted challenge #39 with any challenges in Cluster 2, so #39 is the maximum distance from Cluster 2 on the map. The stress value (0.2919) is well below the acceptable upper limit of 0.39, indicating the two-dimensional map is a good statistical representation of the sorted data and is unlikely to be random or without structure (Rosas & Kane, Citation2012). The research team determined an 8-cluster solution represented the most useful conceptual grouping of challenges sorted by participants. The research team also identified five challenges that they considered a better conceptual fit in an adjacent cluster. After checking that quantitative spanning and bridging data generated during the multidimensional scaling supported re-drawing the cluster boundaries to accommodate this conceptual interpretation, the cluster boundaries were re-drawn accordingly (see – dashed lines indicate original cluster boundaries). Clusters are numbered from highest (Cluster 1) to lowest (Cluster 8) mean impact rating and named to reflect the challenges in each.

Figure 2. Cluster map illustrating the eight focus areas of challenges for CSCs returning to sport post-COVID-19 shutdown.

Cluster 1: Managing additional demands on volunteers contains eight challenges and has the highest cluster mean impact rating (3.94). This cluster contains challenge #30, the challenge with the highest mean impact rating, and all challenges in this cluster are above the all-statement mean impact rating. Cluster 1 also has the highest cluster mean capacity/ability rating (3.53).

Cluster 2: Maintaining club culture is the joint smallest cluster (5 challenges) and has the third-highest cluster mean capacity/ability rating (3.43).

Cluster 3: Implementing health protocols contains eight challenges, including challenge #31, the challenge with the highest mean capacity/ability rating (3.88).

Six of the eight challenges in Cluster 4: Engaging and retaining members are above the all-statement mean impact rating.

Cluster 5: Managing finances is the largest cluster, containing 15 challenges, eight of which are in Q1 of the go-zone.

Cluster 6: Accessing facilities is the joint smallest cluster (5 challenges) and was identified as the cluster that clubs have the least capacity/ability to overcome (3.20). Challenge #55 is not a good conceptual fit with other challenges in this cluster, and the similarity matrix and spanning information shows this challenge was sorted relatively frequently with challenges located in different regions of the map (e.g. with #35, #12, #27, and #54).

Cluster 7: Creating meaningful competition (11 challenges) contains just two challenges in Q1 or Q2.

Cluster 8: Establishing governance and division of responsibility has the lowest cluster mean impact rating (2.91), and the second-lowest cluster mean capacity/ability rating (3.29).

While the mean impact rating for each cluster varies, the mean all-statement impact rating is relatively high (3.28), and every cluster contains at least two challenges in Q1 or Q2. shows the challenges within each cluster, including the five challenges incorporated into neighbouring clusters. also contains the mean impact and ability/capacity ratings for each challenge. also displays the statements colour-coded by cluster.

T-test results

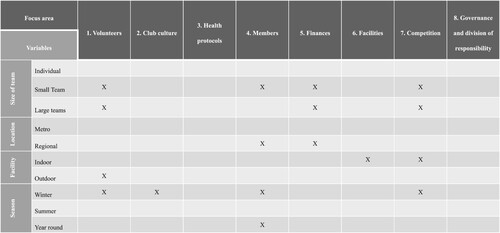

The 54 sub-group analysis t-tests across the 8 cluster mean impact ratings revealed statistically significant differences in all five sub-groups and across six of the eight clusters (not Establishing governance and division of responsibility or Implementing health protocols) (see ).

Table 3. Differences in mean cluster impact ratings by club sub-group.

Discussion

The challenges identified by CSCs in returning to sport after the COVID-19 shutdown demonstrate the complexity and enormity of the task, as perceived by clubs. They reflect an exacerbation of previously recognised human resource, financial, infrastructure, external relationship, and policy challenges to the sustainable delivery of community sport opportunities (Doherty et al., Citation2014), alongside the emergence of new COVID-19 related challenges of maintaining club culture, implementing new health protocols, engaging and retaining members and providing meaningful competition opportunities. The sport sector has previously addressed individual issues such as safeguarding children and the responsible service of alcohol by developing guidelines and improving the governance and regulation of CSCs in Australia (cf. Australian Sports Commission, Citation2019; Good Sports, Citation2020; Mountjoy et al., Citation2020). However, COVID-19 is a multifaceted issue and returning to sport during or following a pandemic requires wide-ranging restrictions to be put in place and managed. Therefore, the contents and implementation of any guidelines ought to be comprehensive enough to address the social, financial, and physical environmental implications of the CSC context. Additionally, sport or health sector guidelines or strategies should recognise the human, context-specific elements in conceptualising problems and solutions associated with COVID-19, and that any additional burden will be shouldered by volunteers (Nichols & Taylor, Citation2010), who may have been stretched to their limit by existing challenges (Doherty et al., Citation2014) and may themselves be dealing with personal impacts of COVID-19.

The following discussion is divided into two sections. First, we map the challenges raised by CSCs in this study on to the primary support resource available in June 2020 by considering the similarities and differences with the Sport Australia Simplified Checklist. Second, we suggest potential supports to provide to CSCs informed by these study findings.

Support available for clubs returning to sport

The Sport Australia COVID-19 Return to Sport Toolkit Simplified Checklist (Sport Australia, Citation2020) recommends that each club designate a COVID-19 Safety Coordinator to complete the Checklist with the aim of developing a COVID-19 Safety Plan. The Checklist includes 69 items across seven topics and 24 sub-categories ().

Table 4. Comparison of Sport Australia’s COVID-19 Return to Sport Toolkit Simplified Checklist (Sport Australia, Citation2020) to the challenges identified by Victorian CSCs.

Four differences were identified between the eight club-generated clusters of challenges in this study and the seven topics in the Checklist. Three club-generated clusters of challenges were not addressed in the Checklist, while clubs identified all but one – Management of illness – of the Checklist topics.

Social challenges (Club culture, Members, and Competition)

The Checklist included many of the physical and economic challenges identified by CSCs. However, the social challenges that clubs perceived as particularly impactful (Club culture and Members) are not on the Checklist. When providing support or guidance to clubs, it should be acknowledged that CSCs are social entities and important community settings where people gather to meet their social needs (Darcy et al., Citation2014; Forsdike et al., Citation2019; Nicholson & Hoye, Citation2008; Spaaij, Citation2009). Previously, events such as natural disasters have compromised the delivery of community sport but never in Victoria has the entire sport sector closed, and CSCs have never been prevented from gathering for any length of time. In the proposed return to sport post-COVID-19 shutdown, social interactions at clubs were restricted with no crowds and no group gatherings pre- or post-training or playing allowed – members had to get in, train, and get out. Participants in this study suggest that these restrictions will severely compromise their club’s ability to meet the social needs of their communities.

Given the social capital CSCs create (Forsdike et al., Citation2019; Girginov, Citation2010; Nicholson & Hoye, Citation2008), it is unsurprising that study participants rated the challenges in the Club culture cluster as the second most impactful (after Volunteers). As such, supporting clubs to retain or rebuild their social culture will be critical to returning to sport following a COVID-19 shutdown. Although ensuring club members share a common focus is a recognised challenge to successfully running CSCs (Doherty et al., Citation2014), CSCs have never had their “social glue” (Spaaij, Citation2009) removed or restricted as it was during the COVID-19 pandemic. The most impactful challenges in the Club culture cluster were those based on creating a community club when there is a need to keep people apart (social distancing); maintaining the strong culture of our club without the potential ability to host functions or have spectators at any of our games/competition; and club culture change from “social” to “get in, train, get out”. The “get in, train, get out” is a specific reference to the principle and motto underpinning the AIS Framework. Participants using this phrase in their responses suggest that adopting this approach will negatively impact the social culture of clubs, and this must be addressed.

Management of illness

The Management of illness topic in the Checklist focuses on identifying and managing people with COVID-19 symptoms, and notifying authorities and other members if a member is symptomatic. The clubs in this study did not identify any potential challenges on this topic, possibly because the main mode of COVID-19 transmission in Australia at the time of data collection was via overseas travellers rather than community transmission (Department of Health and Human Services, Citation2020) and CSCs had never previously faced pandemic-related illness challenges. Clubs identified challenges in implementing new health protocols to prevent illness but not challenges in dealing with or managing someone linked to the club who is ill. This illustrates that the findings of this study represent the “perceived” challenges clubs identified at the time of the study and highlights the importance of having a comprehensive Checklist for clubs to complete, including external, expert-identified challenges clubs may not have considered.

Engagement

The engaging and retaining Members cluster contained four challenges rated below the all-statement average for ability/capacity. This suggests a new challenge for clubs, which could benefit from support and guidance in addressing. The challenges in this cluster were around engaging existing members back to the club, retaining members once up and running again, attracting new participants and volunteers, and ensuring the modified activities developed to meet the social distance-related COVID regulations are engaging for participants. This cluster of challenges reflects the “re-engaging after restrictions” theme identified by Elliott et al. (Citation2021) in their study of the impact of COVID-19 on youth participation and retention. Never have CSCs been faced with challenges to retaining and re-engaging their entire member base following an extended and comprehensive shutdown. Engaging new members will be critical for the ongoing viability of CSCs (Parnell et al., Citation2019) and returning to sport could be one strategy to rebuild community and social connection (Spaaij, Citation2009).

Competition

The Competition cluster included concerns about the uncertainty of the current situation and the need to provide a high-quality competition for members. This included concerns about modifying sport to meet physical distancing requirements, while simultaneously keeping it engaging and competitively meaningful. The relative positions of the Competition, Health protocols, and Engagement clusters on the map () suggest an interplay between these three concepts. One possible interpretation, supported by the work of Elliott et al. (Citation2021), is that providing meaningful competition could facilitate re-engagement of club members while, paradoxically, adhering to health protocols to restrict participant numbers, enforcing social distancing, and sanitising hands and playing equipment, are barriers to providing meaningful competitive experiences for members. The Checklist prompts clubs to consider amending fixtures, playing and training rules, or sporting activities to ensure physical distancing is maintained. However, the challenges associated with doing this, while retaining the integrity of a competitive experience and re-engaging members are not on the Checklist.

Comparing items in each Checklist topic with the challenges within each cluster of this study highlights other differences between the types of challenges CSCs identified and the items in the Checklist, as well as a difference in how community-based sport club volunteers contextualised each topic. For example, the Checklist topic of Finance includes three items focused on determining the cost of new safety measures, defining success, and communicating fee changes to members. By comparison, the Finances cluster in this study amplified pre-COVID-19 pandemic challenges (e.g. unpredictable expenses and revenue and diminished sources of alternative revenue) (Doherty et al., Citation2014) and identified new challenges like understanding the financial stressors on members and providing participants with value for money. This highlights that CSCs were cognisant of the internal and external pressures on their members, the capacity of their volunteers to manage more complex financial transactions, and the additional pressure on the long-term viability and financial security of their club.

Volunteers were another topic in which already existing challenges (Doherty et al., Citation2014; Mooney & Hickey, Citation2019; Parliament of Victoria, Citation2004) were exacerbated, and a comparison of Checklist items with cluster map challenges has highlighted the complexity of the CSC environment. The Checklist prompted clubs to consider the safe working environment of their setting by educating volunteers about transmission control and ensuring reduced in-person contact where possible, alongside considering promoting mental health and wellbeing support services. Clubs in this study identified challenges such as additional pressure and demand on volunteers, having enough volunteers to deliver on requirements, putting volunteers at risk, and retaining and recruiting volunteers. This demonstrates that the volunteer issue is more complex than providing a safe environment and suggests that the volunteer capacity challenges CSCs faced before COVID-19 (Doherty et al., Citation2014; Parliament of Victoria, Citation2004) were amplified. The notion of volunteer risk and the additional pressure on volunteers were also identified by Elliott et al. (Citation2021), and they extend the complexity of drivers acknowledged in Wicker and Hallmann’s (Citation2013) multi-level framework of sport volunteer engagement by including new COVID-19-specific challenges.

This study was not undertaken to evaluate the Checklist, and the aim for clubs in completing the Checklist was not to identify and address club-specific challenges. However, comparing the Checklist topics and items with the challenges CSCs identified and considered impactful has provided insights into: (1) the complexity of the community sport environment; (2) how CSCs conceptualise the task of returning to sport; and (3) the issues clubs were most concerned about – predominantly those of a social nature – that were not been identified or addressed by available resources. It highlights the importance of engaging with both those working at the “coalface” of sport and “experts”, so that policy and best practice guidelines are comprehensive and relevant to those who are ultimately required to implement them. It is also an example of the inherent difficulties of developing sport policy at the national level – the Toolkit was developed by Sport Australia with input from national sport organisations (Sport Australia, Citation2020) – that requires interpretation, translation, and implementation by volunteers at the grassroots level (Skille, Citation2008).

Further support for clubs to overcome the challenges identified in this study could be forthcoming from state or national sporting associations. However, the sport sector worldwide experienced significant COVID-19 pandemic-related job losses (ABC, Citation2020; Nhamo et al., Citation2020; Sheptak & Menaker, Citation2020). In Australia, sport governing body workforces have been significantly reduced, a challenge clubs identified in this study that has contributed to a perceived lack of guidance, decision-making, and leadership. Therefore, the return to sport relies heavily on club volunteers with limited and frequently conflicting governing bodies or facility management support.

A positive observation in this study was that clubs felt they had the ability/capability to overcome most of the challenges they perceived, but their most pressing concern was the pressure on volunteers to do so. This fear could be well-founded (Elliott et al., Citation2021). The COVID-19 return to sport had the potential to exacerbate the pressure on volunteers who may have limited time, expertise, resources, and capacity to deal with potentially challenging issues (Nichols & Taylor, Citation2010; Wicker & Hallmann, Citation2013). Additionally, volunteers may have been impacted personally by COVID-19 through job losses, home-schooling children, or personal health concerns (particularly for volunteers in at risk groups). Although not the primary focus of this study, our research does not support the previous commentary suggesting the COVID-19 pause on sport is an opportunity for an innovative and inclusive reset to sport (Clarkson et al., Citation2020; Fitzgerald et al., Citation2020). The lived experience uncovered by listening to CBCs was that volunteers were focused on how they could deliver their core activities – both social and competitive – and continue to engage and retain their existing members and volunteers. We doubt that the significantly reduced sport sector will be in a position to provide the considerable support CSCs would need to extend themselves to engage and include new non-traditional members or target populations.

Potential support that could be offered

Nine challenges were rated by clubs above the all-statement average for impact and below the all-statement average for ability/capability to overcome (#12, #16, #19, #22, #33, #36, #48, and #50). These challenges can be categorised into two broad themes:

Managing and delivering sport in an uncertain environment:

Planning and structuring a meaningful, competitive season with fluctuating start dates;

Budgeting in an uncertain environment; and

Accessing necessary facilities.

Maintaining the social environment and the capacity to deliver sport:

Engaging participants back to the club;

Retaining volunteers in a pressured environment; and

Maintaining club culture in the face of restrictions on how many people can attend the club at one time, and reduced social activities.

Support to build the capacity of CSC volunteers in these two areas would be particularly beneficial. Specifically, targeted support on how to overcome these exacerbated and new challenges, in addition to the checklist and templates already available, and guidance on how sport can continue to meet the social needs of members. Strong support structures that address the challenges identified in this research could improve the retention of volunteers and the viability of CSCs in the future.

Sub-groups of clubs differed in their perception of the impact of challenges identified in this study. How these differences could shape future support offered to clubs in return to sport scenarios are now discussed.

Individual vs. team sports (small and large)

Clubs providing small team sports indicated Members- and Competition-related challenges were more impactful than clubs that provided individual or large team sports. This may be because clubs providing small team sports had fewer playing members to draw on than larger teams and fewer opportunities to modify activities compared to individual sports. Clubs that provide larger teams sports may require more support to manage the financial implications of returning to sport than clubs that provided individual or small team sports. With a potentially larger membership base, the additional financial challenges for clubs that support larger teams may be related to managing the refunding of member fees while continuing to service the fixed costs of club maintenance.

Club location (Metro Melbourne vs. Regional/rural Victoria)

Clubs based in regional/rural communities rated the impact of the Finances and Member challenges higher than metropolitan-based clubs. Regional clubs might be at greater risk of losing sponsorship due to a smaller pool of potential sponsors to draw from. Additionally, regional clubs may be more directly connected with their local community and aware of the immediate financial impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on their members. Therefore, clubs located in regional/rural locations would benefit from targeted financial support.

Club venue (Indoor vs. Outdoor vs. Indoor and outdoor)

Clubs that used indoor sport facilities were subject to additional restrictions in returning to sport, and this was evident in our findings. These clubs rated the impact of the Facilities-related challenges significantly higher than clubs that used outdoor facilities. Support for clubs that use indoor facilities could include strategies to maximise the space available to deliver activities and engage with members.

Season of operation (Winter vs. Summer vs. Year-round)

Clubs that offer winter sport rated the impact of four types of challenges – Volunteers, Club culture, Members, and Competition – significantly higher than clubs that offer summer or year-round sport. This may be because these issues were more immediately pertinent for winter sports, given the timing of data collection (middle of the Australian winter) and return to sport was imminent.

These comparative results can be presented in an impact matrix (), showing the sub-categories of clubs and the potential degree of effort required to overcome the challenges in returning to sport. For example, these results suggest that at the time of this research, regional or rural clubs providing small team sports using indoor venues during winter (e.g. a regional, winter-only, indoor basketball club) would need to work much harder to address Member-related challenges than metropolitan clubs providing individual sports using outdoor venues in summer (e.g. a metropolitan, summer-only outdoor swimming club). Our research shows that a one-size-fits-all approach to supporting CSCs is unlikely to meet the needs of all clubs. The matrix could provide those supporting CSCs with a guide to where and how to effectively deploy their limited resources.

There are strengths and limitations to consider for this study. Although concept mapping is a time-consuming multi-step process for participants, a strength of this study is that 57 participants took part in the brainstorming activity, and 34 contributed data to all phases. This optimised the fit between the visual representation and the sorting data (Rosas & Kane, Citation2012). In addition, there was a relatively even balance of male and female participants, who were mainly club presidents and secretaries (previously shown to be knowledgeable about club activities (Donaldson et al., Citation2003)). In addition, participants can be considered knowledgeable as 65% had 3+ years of experience in administration roles at their club. Also, our sample of metropolitan and regional/rural reflects the proportion of the population who live in these locations (The State of Victoria Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning, Citation2020), and is a good mix of sports across different competitive seasons (summer, winter, and year-round), types of sport offered at clubs (individual, small team, and large team), sizes of clubs (<100, 100–200, and >200 playing members) and types of playing members (junior only, junior and senior, and senior only playing participants).

A potential limitation of the concept mapping method is the number of processes in which researchers make subjective decisions, for example, when: (1) Synthesising the 173 brainstormed challenges down to 68 unique statements for sorting and rating; (2) Deciding on the final number of clusters that best represent the data; and (3) Deciding on which statements are a better conceptual fit in neighbouring clusters. There is potential that other research groups may have made different decisions at each of these steps, leading to different results. However, we closely followed the detailed guidance of Kane and Trochim (Citation2007) to limit researcher bias in the results. Another potential limitation is that CSCs might have had accessed the Sport Australia Checklist in May 2020 before being recruited for the study in June 2020. This may have influenced the challenges stated by participants.

Conclusion

The CSC environment is complex, and the perceived challenges in returning to sport after the COVID-19 shutdown were multifaceted and context-specific. Our study provides new empirical evidence to support the previously postulated challenges to the return to community sport (Doherty et al., Citation2020), including exacerbation of already existing human resources, financial and infrastructure capacity challenges, and policy challenges related to the local interpretation and implementation of government public health policy directives. In addition, the emergent club culture, participant/volunteer engagement, and creating meaningful competition challenges in our study reflect the “re-engaging” construct previously identified by Elliott et al. (Citation2021).

Our research shows that listening to CSCs to understand these challenges is critical to providing the type and volume of support needed to ensure the sustainability of grassroots sport. Although this study was conducted in the middle of a crisis, a global pandemic, one of the lessons that it provides is that making a conscious effort to listen to the people at the “coalface” of grassroots and community sport is essential if policies and recommended practices are to be well-received, meaningful, and ultimately, effective. This study was not designed to compare Sport Australia’s checklist with the views of CSCs for the purpose of claiming that one or the other was more relevant, but it has highlighted that top-down and bottom-up approaches working in concert are likely to be better than one or the other in isolation. An illustration of this is that the overarching concerns of CSCs were often how they could operate in an uncertain financial and policy environment, not just what they should do in response to specific challenges; both need to be explored and subsequently addressed. This study has also demonstrated that it is unwise to treat CSCs as a homogenous group. Often their similarities outweigh their differences, but in this study and confronted by a specific set of challenges posed by the pandemic, there are important differences across a range of criteria that might usefully inform future work.

One of the most important tensions identified in this study was between the “social” dimension of CSCs and the top-down directive to “get in, train, get out”. In essence, the health and safety protocols associated with managing a return to sport in a COVID-19 environment mean that CSCs are forced to focus, largely, on attending to the physical health needs of members. In doing so, clubs are constrained in their ability to contribute to the social and emotional needs of members, at least not in-person. For organisations that are recognised to contribute to the social capital of communities (cf. Nicholson & Hoye, Citation2008), this tension, broadly conceptualised as between the physical and the social/emotional, which are not opposites nor mutually exclusive in “normal” times, threatens the very fabric of CSCs. Alongside the COVID-19 pandemic providing CSCs with an opportunity for innovation and new practices, as some have suggested (Doherty et al., Citation2020; Elliott et al., Citation2021; Fitzgerald et al., Citation2020), it is also equally possible that the COVID-19 global pandemic reduces CSCs to a pale imitation of what they once were, forced to continue with less resources, less volunteers, less members, with more uncertainty, and under more pressure to adhere to government and governing body protocols. What this study has shown is that if CSCs are to thrive and not just survive post-pandemic, then much more support and guidance will be required not just from the sport governing bodies, but from the entire sport sector.

Ethics approval

The Latrobe University human research ethics committee approved the study (HEC20249).

Acknowledgements

We greatly appreciate the time and contributions of all study participants.

References

- ABC. (2020, June 30). Coronavirus pandemic job losses from major Australian employers. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-06-30/job-losses-coronavirus-australia-covid-19/12401232

- Ausplay. (2019). Sport Australia’s national survey data on sport and physical activity. Sport Australia. https://www.clearinghouseforsport.gov.au/research/smi/ausplay/results/national

- Australian Sports Commission. (2019, July 8). Child safe sport. Australian Government. https://www.clearinghouseforsport.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0011/783884/Child_Safe_Sport_Framework_Jurisdictional_Screening_and_Mandatory_Reporting_Requirements_8_July_2019.pdf

- Australian Sports Foundation. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 on community sport. Australian Sports Foundation. https://covid.sportsfoundation.org.au/

- Boston Consulting Group. (2017). Intergenerational review of Australian sport 2017. Boston Consulting Group. https://www.sportaus.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0011/660395/Intergenerational_Review_of_Australian_Sport_2017.pdf

- Clarkson, B. G., Culvin, A., Pope, S., & Parry, K. D. (2020). Covid-19: Reflections on threat and uncertainty for the future of elite women’s football in England. Managing Sport and Leisure. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2020.1766377

- Darcy, S., Maxwell, H., Edwards, M., Onyx, J., & Sherker, S. (2014). More than a sport and volunteer organisation: Investigating social capital development in a sporting organisation. Sport Management Review, 17(4), 395–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2014.01.003

- Department of Health. (2018). Sport 2030. Department of Health. https://www.sportaus.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/677894/Sport_2030_-_National_Sport_Plan_-_2018.pdf

- Department of Health. (2020). Coronavirus (COVID-19) national principles for the resumption of sport and recreation activities. https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/coronavirus-covid-19-national-principles-for-the-resumption-of-sport-and-recreation-activities

- Department of Health and Human Services. (2020, September 25). Victorian coronavirus (COVID-19) data. Retrieved September 25, 2020, from https://www.dhhs.vic.gov.au/victorian-coronavirus-covid-19-data

- Doherty, A., Millar, P., & Misener, K. (2020). Return to community sport: Leaning on evidence in turbulent times. Managing Sport and Leisure. http://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2020.1794940

- Doherty, A., Misener, K., & Cuskelly, G. (2014). Toward a multidimensional framework of capacity in community sport clubs. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 43(2S), 124S–142S. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764013509892

- Donaldson, A., Hill, T., Finch, C., & Forero, R. (2003). The development of a tool to audit the safety policies and practices of community sports clubs. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 6(2), 226–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1440-2440(03)80258-X

- Elliott, S., Drummond, M. J., Prichard, I., Eime, R., Drummond, C., & Mason, R. (2021). Understanding the impact of COVID-19 on youth sport in Australia and consequences for future participation and retention. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 448. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10505-5

- Evans, A. B., Blackwell, J., Dolan, P., Fahlén, J., Hoekman, R., Lenneis, V., McNarry, G., Smith, M., & Wilcock, S. (2020). Sport in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic: Towards an agenda for research in the sociology of sport. European Journal for Sport and Society, 17(2), 85–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/16138171.2020.1765100

- Fitzgerald, H., Stride, A., & Drury, S. (2020). COVID-19, lockdown and (disability) sport. Managing Sport and Leisure. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2020.1776950

- Forsdike, K., Marjoribanks, T., & Sawyer, A. M. (2019). ‘Hockey becomes like a family in itself’: Re-examining social capital through women’s experiences of a sport club undergoing quasi-professionalisation. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 54(4), 479–494. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690217731292

- Fullagar, S. (2020). Recovery and regeneration in community sport: What can we learn from pausing play in a pandemic? Medium. https://medium.com/the-machinery-of-government/recovery-and-regeneration-in-community-sport-9a217bd70aef

- Girginov, V. (2010). Culture and the study of sport management. European Sport Management Quarterly, 10(4), 397–417. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2010.502741

- Good Sports. (2020). Managing Alcohol in your Club. Alcohol and Drug Foundation. https://goodsports.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Managing-Alcohol-in-your-club.pdf

- Hughes, D., Saw, R., Perera, N. K. P., Mooney, M., Wallett, A., Cooke, J., Coatsworth, N., & Broderick, C. (2020). The Australian Institute of Sport framework for rebooting sport in a COVID-19 environment. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 23(7), 639–663. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2020.05.004

- Kane, M., & Trochim, W. M. (2007). Concept mapping for planning and evaluation: Vol. 50. Sage Publications.

- Ludvigsen, J. A. L., & Hayton, J. W. (2020). Toward COVID-19 secure events: Considerations for organizing the safe resumption of major sporting events. Managing Sport and Leisure. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2020.1782252

- Mannes, M. (1989). Using concept mapping for planning the implementation of a social technology. Evaluation and Program Planning, 12(1), 67–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/0149-7189(89)90024-4

- Mooney, A., & Hickey, C. (2019). The place of social space. In S. Pinto, S. Hannigan, B. Walker-Gibbs, & E. Charlton (Eds.), Interdisciplinary unsettlings of place and space (pp. 31–44). Springer.

- Mountjoy, M., Vertommen, T., Burrows, K., & Greinig, S. (2020). #Safesport: Safeguarding initiatives at the youth Olympic games 2018. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 54(3), 176–182. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2019-101461

- Nhamo, G., Dube, K., & Chikodzi, D. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 on the global sporting industry and related tourism. In Counting the cost of COVID-19 on the global tourism industry (pp. 225–249). Springer.

- Nichols, G., & Taylor, P. (2010). The balance of benefit and burden? The impact of child protection legislation on volunteers in Scottish sports clubs. European Sport Management Quarterly, 10(1), 31–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184740903554058

- Nicholson, M., & Hoye, R. (2008). Sport and social capital. Elsevier.

- Parliament of Victoria. (2004). Inquiry into Country Football. Rural and Regional Services and Development Committee. Retrieved March 18, 2021, from https://www.parliament.vic.gov.au/images/stories/committees/rrc/footy/cf_report.pdf

- Parnell, D., May, A., Widdop, P., Cope, E., & Bailey, R. (2019). Management strategies of non-profit community sport facilities in an era of austerity. European Sport Management Quarterly, 19(3), 312–330. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2018.1523944

- Rosas, S. R., & Kane, M. (2012). Quality and rigor of the concept mapping methodology: A pooled study analysis. Evaluation and Program Planning, 35(2), 236–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2011.10.003

- Sheptak, R. D., & Menaker, B. E. (2020). When sport event work stopped: Exposure of sport event labor precarity by the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Sport Communication, 13(3), 427–435. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijsc.2020-0229

- Skille, E. A. (2008). Understanding sport clubs as sport policy implementers. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 43(2), 181–200. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690208096035

- Spaaij, R. (2009). The glue that holds the community together? Sport and sustainability in rural Australia. Sport in Society: The Social Impact of Sport, 12(9), 1132–1146. http://doi.org/10.1080/17430430903137787

- Sport Australia. (2020). Return to sport. https://www.sportaus.gov.au/return-to-sport

- The State of Victoria Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning. (2020). Population and housing in regional Victoria: Trends and policy implications. https://www.planning.vic.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0035/469178/Population-and-Housing-June-2020.pdf

- Trochim, W. M., & McLinden, D. (2017). Introduction to a special issue on concept mapping. Evaluation and Program Planning, 60(1), 166–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2016.10.006

- van Bon-Martens, M. J., van de Goor, L. A., Holsappel, J. C., Kuunders, T. J., Jacobs-van der Bruggen, M. A., te Brake, J. H., & van Oers, J. A. (2014). Concept mapping as a promising method to bring practice into science. Public Health, 128(6), 504–514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2014.04.002

- Wicker, P., & Hallmann, K. (2013). A multi-level framework for investigating the engagement of sport volunteers. European Sport Management Quarterly, 13(1), 110–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2012.744768