Abstract

This article regards museums of world religions as intersemiotic sites where the knowledge of individual religions as well as religion as a broad concept is socially constructed. It examines the role of verbal interpretations in co-constructing knowledge of religion with other visual and spatial semiotics. The case study is based on a comparison of the text panels and the display cases on Christianity in two museums: St Mungo Museum of Religious Life and Art (SMM) in Glasgow, and Museum of World Religions (MWR) in Taipei. The methodology combines the micro-level analysis of theme-rheme pattern in information progression, logical-semantic relations in verbal-visual interaction, and a pragmatic account of the two epistemic communities in which the museums are situated. The results suggest that through the interaction between the text panels, labels, and individual objects, each museum has construed its own material definition of religion. Specifically, Christianity is construed as a phenomenon perceived by Christians in SMM, whereas in MWR, the knowledge of Christianity develops from the holy scriptures.

1. Introduction: religion, museums, and museums of world religions

This article aims to systemically investigate the role of verbal interpretations in the social construction of religious knowledge in a three-dimensional intersemiotic museum space, and ultimately leads to a material definition of religion. Verbal interpretations will be investigated co-spatially with other visual and spatial semiotics in the museum, based on the case studies of the exhibition of Christianity in two museums that compare different religions, more commonly referred to as world religions museums (Orzech Citation2020, 3)Footnote1: St Mungo Museum of Religious Life and Art (SMM) in Glasgow, Scotland, and the Museum of World Religions (MWR) in Taipei, Taiwan. The two museums are chosen for comparison because of the different approaches they adopted in constructing the knowledge of religion.

Until fairly recently, religion had not received much attention from either museum exhibitions or scholarly research. As for the former, the reason could be attributed to museums being associated with rational and scientific thinking, as is the case with the Western history museums, which were born from eighteenth-century Enlightenment thought (Buggeln Citation2012, 34). This move to replace faith with science seems to explain why religious objects remained excluded from museum spaces for a long time. In museums, objects were organised and labelled according to the framework of modern science. Even when religious objects did enter the museums, they were often ‘museumised’ and secularised, that is, removed from their religious functions and original context. Clifton (Citation2007, 109) points out that Western museums tended to guide visitors either to the ‘cultural and historical resonance’ of religious objects, particularly with non-Western religions, or to the ‘visual wonder at their aesthetic uniqueness’, more often with Western religious items such as Christian art. Therefore, for a long time, museums of religions seemed a concept contradictory to established museology.

The turning point in the tension between museum and religion came probably with the advent of ‘new museology’ at the end of the 1980s (Vergo Citation1989), which saw the function of museums changing from preserving and collecting objects to a more community-inclusive agenda of reaching out to the visitors. Along with the movement of immigrants who bring with them new religions and cultural beliefs, religious displays in museums have been seen as a way of fostering interfaith dialogue and promoting cross-cultural understanding (Da Silva Citation2010, 167). The global conflicts under the disguise of religious differences have also prompted religious education through different media, including museum exhibitions. It is against this background that we have seen the establishment of museums devoted to a particular religion, as well as museums of world religions, which may be defined as ‘public and permanent collection[s] of material relating to more than one religion and representing the belief systems of more than one country which also interprets the religious meaning of objects in display’ (Carnegie Citation2009, 158). Orzech (Citation2020) conducted a comprehensive research on five museums of world religions: the Religionskundliche Sammlung in Marbug, the State Museum of the History of Religion in St. Petersburg, Le Musée Des Religions du Monde in Québec, SMM in Glasgow, and MWR in Taipei. All these museums exhibit what they consider as major religions in the world, and to a different degree, aim to promote understanding of different religions. Some of these museums have a stronger academic interest, while others focus more on community inclusion.

However, despite the recognition of the benefits of religious display in museums in modern society, religious objects are mostly secularised in the museum space. In most cases, museums make the effort to emphasise explicitly to the visitors that this is a secular and ‘safe’ place to discuss religion, as in the case of SMM (Carnegie Citation2009, 166). Buggeln (Citation2012, 41) explains that museums are comfortable in introducing religion as a ‘generic transcendent experience’ but are cautious not to be seen as promoting a particular religious belief. Museums are understood as a place to popularise specialised knowledge and educate the public, not as a space where religious practice should take place. For example, the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) is proud of its collections from different religious cultures and traditions, but rejects the suggestion of building a prayer room. The reason, as the director explains, is that the museum is expected to be a space ‘which is consciously civic’ (Knott Citation2019). In this sense, the tension between museum and religion is not completely resolved, and there is much debate about religious museums as a research topic.

The fundamental challenge to the study of religious museums is whether religion can be represented or introduced to the visitors through material objects, and if yes, how. Museums, as a material-based exhibition space, tend to deal with religion as ‘a practice involving material things and what people do with them and say about them’ (Orzech Citation2020). However, the question here is what counts as a religious or sacred object or whether such objects even exist, as some argue that objects are only religious when they perform religious functions in religious rituals by religious followers. When they are removed from the religious context, they are neither spiritual nor transcendent. Paine (Citation2013, 3) illustrates the issue of whether things can be holy by bringing up the debate of how bread and wine can be the body and blood of Christ. While the Catholic Church believes in the theory of transubstantiation, some hold the view that these objects are symbolic and only become religious because of the faith of the receivers of bread and wine. This example illustrates the complexity faced by museums in defining religious objects – whether religiousness is inherent in the nature of objects or whether it comes to fore only in religious settings through religious rituals.

Another question is, even if museums can identify objects that are either of religious nature or have implications or associations with religion, how these objects can educate visitors about religion. For many religious believers, people’s experiences with sacred objects are inexpressible and such a non-material dimension cannot be displayed in a museum space. This view highlights the important link between religious objects and their users. Catalani (Citation2004, 10) argues that it is almost impossible ‘to reveal the invisible essence, the sacred meanings, the collective memories and the beliefs behind religious objects’.

Furthermore, as education is an important agenda in the five museums of world religions discussed in Orzech (Citation2020), how an exhibition of religion can promote the visitors’ understanding of religions is also widely debated. Ching-Ju Liao (Citation2006, 72), the assistant curator of MWR, draws from the four components of religion: concepts, practices, experience, and rituals in the sociological approach to religion (Durkheim Citation1915), and argues that except for rituals, the other three components are all non-material, and can only be explained to the audience through verbal interpretations provided by the museum. On the other hand, O’Neil (Citation2006, 41) the former curator of SMM, places more emphasis on the emotions that can be aroused from objects, as sources of inspiration to the visitors. Orzech (Citation2020, 40) sees the relationship between the material objects and ‘the scientific reduction of complex processes, relationships, things, and technologies to abstract labels and concepts’ as a competitive one in the museum space.

This study follows up on this debate about the tension between objects and texts. In a sense, this is not too different from the other discussions centred around museums – whether museums should only be visual and experiential, or whether there is room for verbal texts. In general, verbal texts are considered lower in the hierarchy of museum communication (Blunden Citation2020). Coxall (Citation1994, 138) warns that if museum text producers are unaware of how meaning is constructed systemically through languages, they cannot control how visitors’ experiences are mediated through museum texts.

Existing studies on religious museums, as discussed above, understandably place emphasis on the visual dimension in the museum space (objects, architecture, internal layout), since this is how museums are different from other media. However, it is clear from their discussions that interpretive texts perform an important function in framing the understanding of the visual display. Buggeln (Citation2012), for example, considers the dynamics in the museum space as shaped by a dialogue between the architecture, the inherent qualities of the objects, and the nature of interpretation. In the discussion of the five museums, Orzech (Citation2020) frequently refers to the interpretive texts, though refraining from further elaboration. In the case of Religionskundliche Sammlung, for example, it was pointed out that the museum considered it necessary to have a director of knowledge to guide the visitors through the collection, but since this could not be realised, they chose to provide ample explanatory labels (Orzech Citation2020, 62). As for Le Musée Des Religions du Monde, it was observed that the textual panels functioned to explain key ideas and items in the display case to the visitors. Thus, it is clear that verbal interpretations may not occupy the top position in museum communication, but they have an essential role to play.

The implementation of multimedia in museum space implies that visitors can learn about the exhibitions through different channels. Csikszentmihalyi and Hermanson (Citation1995) categorise museum learning as having three elements: sensory (visual, aural, and kinaesthetic); intellectual (rational, scientific, and historic); and emotional (empathetic and self-reflective). In the study of religious museums, sensory and emotional experiences have received more attention than intellectual learning, which may be related to the nature of religious experiences. Furthermore, Arthur (Citation2000, 5) states that ‘when it comes to religion, the relationship between information and insight cannot be plotted in a straightforward quantitative way’. Lengthy explanations in museum texts fail to attract visitors’ attention and do not help their learning (Da Silva Citation2010, 187). Previous studies have revealed that visitors emotionally respond to exhibitions of religious art. Clifton (Citation2007) studied visitors’ comments on the exhibition The Body of Christ in the Art of Europe and New Spain, 1150–1800 organised at the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston and found that the visitors regarded the exhibition as ‘moving’, ‘inspirational’, and ‘soul stirring’ (111). Berns (Citation2015, 48) reported that at the British Museum exhibition Images and Sacred Texts: Buddhism Across Asia, a visitor was found mimicking the hand gesture of one of the Buddhist statues. Such responses confirm the sheer impact of the visual aspect of objects on the visitors.

However, while visual and sensory experiences resulting from the interaction between visitors and a displayed artefact remain the most important element in museum visiting, verbal texts play an important role to ‘add “something more” to the experience gained by looking alone’ (Blunden Citation2020, 46). This ‘something more’ provided by texts is even more important for visitors who are less familiar with the exhibition theme, as existing studies have suggested that visitors rely more on the mediation of verbal texts for their interaction with objects from a different culture because it is more difficult for them to identify a common ground with the objects (Lidchi Citation1997, 166). For a museum that would like to encourage visitors to learn about different cultures, something that they are not familiar with, it perhaps requires more than emotional and sensory learning, and verbal interpretations have a role to play in intellectual learning of different religions.

Against this background of intellectual learning in museums of world religions, this study brings to the foreground the role of verbal interpretations that are often ignored in other studies of religious museums, and analyses how these texts co-construe meaning with other multimodal semiotics in the wider museum surroundings, including visuals, space, participants, and institutions. With this aim, the next section will further explore the role of verbal interpretations in museum learning.

2. Museum texts, knowledge, and information

This section draws from the disciplines of discourse analysis and systemic functional grammar to identify and define useful concepts that allow us to make concrete the relationship between the abstract concepts of intellectual museum learning and linguistic production in museum texts. The specific concepts that will be defined and reviewed include knowledge, information, and theme.

It is important to define the term knowledge at the outset. In their study of knowledge in a textbook, van Dijk and Atienza proposed an empirical definition of knowledge: ‘we practically define as knowledge of an epistemic community the beliefs that are presupposed in the public discourses of that community’ (Citation2011, 96). This is similar to what Von Stuckrad (Citation2013) considers as a useful concept to be incorporated into the theoretical framework to the study of religion. He follows Foucault’s (Citation1981) understanding of discourse and argues that knowledge is ‘the cultural response to symbolic systems that are provided by the social environment’ (Von Stuckrad Citation2013, 8).

This view of knowledge as constructed socially is different from the more philosophical perspective of knowledge, which is often understood as ‘factual knowledge’ or ‘justified true beliefs’ (see the discussion in Wray Citation2002). In other words, in this study, we do not attempt to explore whether museum texts provide an accurate account of the concept of religion or a particular religion, for example, Christianity. Rather, we are interested in what the museum assumed to be the beliefs of, or the cultural response of the epistemic community in which the museum is located.

Van Dijk and Atienza (Citation2011) highlight two important dimensions of this more empirical definition of knowledge: interactive and discursive. Knowledge is interactive, because it is acquired, shared, and used through interaction among epistemic communities (Van Dijk and Atienza Citation2011, 97); and is discursive because it is expressed, presupposed, verified, and challenged through different media and genres (TV, films, textbooks, cultural institutions such as museums), in various modes (written, spoken, digital, etc.). Based on this discussion, two theoretical premises can be established for our research. First, discourse is an important resource through which our knowledge of the world is constituted and distributed. Second, knowledge is produced in such a way that text producers need to take into consideration other members of the epistemic communities. Knowledge needs to come from somewhere – we do not start with ground zero every time. Text producers need to assess what text receivers may already know or accept, and build from there.

Discourse is one of the most difficult terms to define in academics, but von Stuckrad’s definition of it is particularly conducive to our discussion of knowledge. He defines discourse as ‘practices that organize knowledge in a given community; they establish, stabilize, and legitimize systems of meaning and provide collectively shared orders of knowledge in an institutionalized social ensemble’ (Von Stuckrad Citation2013, 15).

Discourse as an abstract concept needs to be realised through a concrete material, for which Von Stuckrad (Citation2013) borrows the term ‘dispositive’ from Foucault (Citation1981), to refer to ‘the totality of the material, practical, social, cognitive, or normative “infrastructure” in which a discourse develops’ (Von Stuckrad Citation2013, 15). This dispositive can be a new governmental policy, a new technology, a published book, or an exhibition in a museum. For example, religious knowledge can be disseminated through religious gatherings, mass media, school education, as well as cultural institutions such as museums and galleries. Because the material affordances of each media and genre differ, the construction of discourse is constrained by but can also take advantage of different semiotics.

For the reasons explained in the previous section, this study focuses on verbal interpretations as a powerful tool within the museum space to contribute to intellectual learning, that is, to bring visitors new knowledge about religion. Broadly speaking, spreading knowledge can be described as adding new knowledge to the existing knowledge of the epistemic communities. To use the linguistic term, what we want to focus on is the concept of information. Linguistically, information is ‘the tension between what is already known or predictable and what is new or unpredictable’, and it is precisely this process of ‘the interplay of new and not new that generates information in the linguistic sense’ (Halliday and Matthiessen Citation2004, 89).

In the model of functional linguistics, information is realised through the grammatical structure of theme (Eggins Citation2004; Halliday and Matthiessen Citation2004). Theme is defined as ‘the element which serves as the point of departure of the message; it is that which locates and orients the clause within its context’ (Halliday and Matthiessen Citation2004, 64). As we usually depart from the place we are familiar with, in linguistic analysis, theme is regarded as what the text producer considers to be familiar to the readers, that is the existing knowledge they share with the text receivers. Whereas anything that is not theme belongs to a grammatical structure called rheme. Rheme presents new information, or what the text producer considers to be unknown to the text receivers. This view of theme-rheme progression not only takes into consideration the grammatical structure of a language, but puts more emphasis on what text producers consider about the text receivers in terms of what they already know, what they do not know, and what they should know.

To put it simply, in a standard sentence structure in English, theme is what comes before the verb. For example, in the sentence An apple is on the table, ‘An apple’ is the theme, and ‘is on the table’ is the rheme. In this information structure, the fruit apple is considered to be known to the text receivers, and where the apple is located is new information. On the other hand, if the sentence is structured as ‘On the table is an apple’, the text producer assumes that the text receiver knows about the existence of a table, but does not know about what is on the table. As communication in daily life takes place multimodally, given and new information can also be communicated non-verbally. For example, an antique table on display in a museum exhibition room can visually form the theme from which new information can be acquired.

This study follows the approach of moving from theme to knowledge to museum discourse. In other words, from the micro-level analysis of theme system, we move to the social construction of knowledge of the epistemic community with which the museums are associated.

3. An analytical model of knowledge

Following our theoretical framework of the link between knowledge, information, and theme, and to take into consideration how languages co-construct meanings of other semiotics in the museum space, this section introduces an analytical method, based on the model of epistemic analysis proposed by Van Dijk and Atienza (Citation2011), the communication framework of museum texts by Ravelli (Citation2006), and the model of text-image relation developed by Martinec and Salway (Citation2005) and Bateman (Citation2014).

With our focus on the construction of knowledge about Christianity in museums, we first collect verbal interpretation data related to Christianity in the two selected museums. The texts are then divided into functional units for a micro-level analysis of theme-rheme pattern. Based on the theme-rheme progression, we uncover what the text producers (that is, the museums) assume to be the existing knowledge of the museum visitors (theme), and what they want to add to this knowledge base (rheme). Regarding the interplay of the new and the given information, we examine the functional discursive-epistemic strategies (Van Dijk and Atienza Citation2011, 101) that add new information to the given information. As Van Dijk and Atienza (Citation2011, 101) argue that ‘learning is traditionally defined in terms of transformations (additions, substitutions, etc.) in the system of knowledge’, an analysis of these transformations indicates how the text producers make the suggestion to the text receivers to extend their knowledge of a topic. summarises the list of strategies adapted from Van Dijk and Atienza (Citation2011) and Ravelli (Citation2006).

Table 1. Main types of functional discursive-epistemic strategies.

Each strategy has its typical linguistic features. For example, narration explains how things happen in temporal sequence and features active verbs (Ravelli Citation2006, 21). Exposition, on the other hand, describes how things are. Expository writings tend to feature being and having verbs, to perform the action of defining, identifying, or giving attributes to a concept (Ravelli Citation2006, 20).

With the linguistic features ascertained, we then examine how the textual panels on Christianity co-construct knowledge with the adjacent display cases and artefacts. New and given knowledge is further constructed through the interplay between the text panel and the object labels (intrasemiotic), and between the objects and the labels (intersemiotic). We can examine these relations based on the logico-semantic relations between text and image (Bateman Citation2014; Martinec and Salway Citation2005) ().

Table 2. Logico-semantic relations between text and image (Bateman Citation2014, 196).

The focus of this study is on the micro-level analysis of text and verbal-visual interaction in religion museums. However, Van Dijk and Atienza (Citation2011) argue that a pragmatic account of the goals of the participants, their identities, and the semiotic space that houses the exhibition is crucial for the micro-level study. For this reason, the following section will give an account of the two museums chosen as case studies for this research and of their spatial features, to provide a clear context for the analysis of verbal interpretations and verbal-visual interaction.

4. The two museums

4.1. Description and environment of the museums

St Mungo Museum of Religious Life and Art (SMM) was opened in 1993 in Glasgow, Scotland, and is managed by the Glasgow City Council. The aim of the museum, as inscribed in the museum entrance foyer, is ‘to promote understanding and respect among people of different faiths, and of none’.

The museum is located in Glasgow’s Cathedral Square, on the site of a medieval castle-complex, and nearby are the Glasgow Cathedral and Glasgow Evangelical Church. The museum building was previously owned by Glasgow Cathedral, but was given to the Glasgow City Council as a site to develop this museum. It is a modern building established in 1989, but its style emulates a medieval castle in Glasgow. The ground floor hosts the reception and a café, and the visitors’ journey starts from the first floor.

The museum hosts three main galleries. The first one, the Gallery of Religious Art, is an open and bright room that houses individual religious artefacts which ‘are chosen to reflect the religious traditions which inspired their creation’ (museum brochure). On the three walls of the gallery are pictures and stained-glass windows of Christian art, including objects with titles such as Three Saints, Old Testament Figures, and Virgin Mary and Jesus. The non-Christian artefacts are placed in the middle of the room, and include objects such as three Buddhist figures, an Egyptian mummy mask, a Turkish prayer rug, and a Nigerian ancestral screen.

Through the first gallery, the visitor can enter the Gallery of Religious Life, which is a small and dark room, with the exhibition organised in a U-shape following the cycle of life from birth and childhood to coming of age, ending with death and afterlife. The gallery also includes a display case on persecution, war, and peace. In the middle of the room, there is a display featuring the world’s six major religions in alphabetical order: Buddhism, Christianity, Hinduism, Islam, Judaism, and Sikhism. The second floor is used for temporary exhibitions. The upper floor houses the Scottish Gallery, with its focus on how religions have influenced Scottish society.

The Museum of World Religions (MWR) was opened in 2001 in New Taipei City, Taiwan. It was founded and is managed by the Ling Jiou Mountain Buddhist Foundation in Taiwan. On the museum’s introductory panel, its aim is described as being to provide an opportunity for people to learn about different religions, so that they can choose a spiritual belief that they would like to follow in their lives, and to guide visitors in making choices by providing them information.

The museum is located on the sixth and seventh floors of a modern commercial building in a busy commercial area, surrounded by shopping malls, banks, and restaurants. Visitors purchase tickets from the designated entrance at the ground floor and take the lift to the museum.

On the seventh floor, there is a shop and a café on one side, with the exhibition starting from the other side. The visitors begin by passing by a wall with a waterfall (with an accompanying label titled ‘purification’), and then walk through a narrow corridor of different figures of religious practitioners, the Pilgrims’ Way, to reach an open space, the Golden Lobby. Passing through the golden lobby, the visitors reach the reception desk and are invited to an auditorium called Creations, to watch an introductory video of how religions account for the origin of life. Next comes the biggest exhibition room of the museum, the Great Hall of World Religions. Ten religions are on display in this hall, including eight major religions of the world: Buddhism, Daoism, Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Sikhism, Judaism (in the order of the number of followers), two ancient religions (Egyptian and Maya), and a section on religions in Taiwan. The visitors can then go downstairs to the sixth floor to visit other exhibition rooms, including the Hall of Life’s Journey, and two other audio-visual rooms that show videos of meditation practices, and speeches from religious leaders of the world.

The two museums share some similarities. Both museums are relatively small in terms of size and space, and include a gallery on the cycle of life and a gallery on world religions. However, there are also some obvious differences. The SMM is more community-oriented and critical, involving contribution from religious leaders in Scotland, and actively explores issues such as wars and conflicts associated with religions. The SMM is located in a place with a strong Christian tradition, and in Glasgow particularly, where there is a long-standing sectarian rivalry between Roman Catholics and Protestants. To discuss world religions against this background, the museum is cautious in emphasising that it is a secular and neutral place for safe discussions on religion: ‘a safe arena which is secular but borders the religious or spiritual domain’ (O’Neil Citation2006, 42).

On the other hand, MWR is founded by a Buddhist organisation in Taiwan, where the majority of the population follows either Buddhism or Taoism. However, the museum denies representing any particular religion. Furthermore, instead of working with the local religious communities as is the case with SMM, the exhibition at MWR is developed by the Center for the Study of World Religions at Harvard Divinity School.

As is evident from earlier discussions, displaying different religions in one space is challenging and difficult. Despite both museums making an effort to emphasise their neutral positions and taking appropriate measures to ensure objectivity, such as presenting religions in the alphabetical order or according to the number of followers, given the social and cultural background and the agents involved, the museums inevitably hold a certain perspective and cannot be ideology-free. For example, the reference to ‘St Mungo’, Glasgow’s patron saint who brought the Christian faith to Scotland, in the name of SMM may give visitors the wrong impression that this is a museum of Christianity. On the other hand, MWR, with a Buddhist foundation as its founder, a gallery named ‘Avatamsaka World’, as well as a café that only offers Buddhist-style vegetarian food, sends the message that the museum is not entirely impartial to any religion as it claims. All these linguistic (e.g. name) and non-linguistic (e.g. architectural style, food) features contextualise the display of artefacts and the interpretation of museum texts, and ultimately influence visitors’ experiences and expectations of the exhibitions.

4.2. The panel of Christianity

The main focus of this study is to bring to the foreground the role of museum texts in presenting religion in the museum space. To achieve this purpose, we choose textual panels on Christianity in both museums for comparison. In SMM, this text panel is located in the Gallery of Religious Life, and in MWR, it is placed in the Great Hall of World Religions. Both panels are placed adjacent to a glass case which includes a number of religious artefacts. The analyses below discuss the information structure in the two textual panels,Footnote2 and the next section will explore how the panel and the display case co-construct knowledge of Christianity.

The textual panels in SMM and MWR contain 71 and 259 words, respectively. and present the analysis of theme-rheme pattern and the discursive-epistemic strategies for developing new information from old information.

Table 3. Theme analysis in SMM.

Table 4. Theme analysis in MWR.

In the panel at SMM, the first theme, Christians, can be understood as what the text producer assumed to be the existing knowledge of the readers. In other words, Christians, the followers of Christianity, is what the museum chose to be the starting point from where the discussion of Christianity develops. As to the rheme, the verb believe represents a mental process of sensing, according to functional linguistics (Halliday and Matthiessen Citation2004, 203). This grammatical structure presents the inner experience of sensors (Christians) and a phenomenon which they sense (Jesus). Therefore, this first clause sets the frame for the following knowledge of Christianity as inner experience of the believers of this religion with Jesus. In this sense, the discursive-epistemic strategy adopted should be regarded as a type of argumentation, that is, the museum is putting forward a point of view, as perceived by a particular epistemic community (Christians). This first clause also places importance on the feelings of religious believers.

The rest of the clauses all begin with the same theme, Jesus, which is the rheme in Clause 1, that is, the main entity that constitutes the inner experience of Christians. Clause 2 extends the knowledge of Jesus by identifying him as the only son of God. Clauses 3–6 further extend this knowledge by providing information of what Jesus has done in a chronological order, from when he was born until after he died. After an argumentation is put forward in the first clause, the discursive-epistemic strategy used in the rest of the clauses is narration (with one instance of exposition). It is noteworthy that all these extensions of knowledge of Jesus are framed by Clause 1, that is, they should all be interpreted as phenomena sensed or believed by the Christians.

We next examine the interplay of theme and rheme in the panel at MWR.

The panel at MWR starts with a quote from the Bible, the holy scripture of Christianity. Quotation as a stylistic convention is often used in report genres such as journalism and academia to ‘serve as the evidential foundation’ (McGlone Citation2005, 511) upon which stories can be developed or arguments can be supported. In the framework of functional linguistics, this quotation is a verbal clause, consisting of the sayer, Jesus, and the verbiage (the content of what is said in the quote), and it can be said that the implicit receiver of this message is the reader of the Bible, or the follower of Jesus. While a mental process represents the inner experience of the sensor, a verbal process transforms the inner experience of the sayer into the outer experience of the receiver. Compared with the panel at SMM, where Christians are the starting point and Jesus is a phenomenon of their inner experience, here, Jesus is the starting point who verbalises his inner experience into the outer experience of his followers, through the acts of listening or reading. Furthermore, by beginning with a quote from the Bible, this panel extends the textual knowledge of what visitors should know about Christianity with the Bible as the evidential foundation.

After the quote, Clauses 1, 2, and 3 introduce three given themes – Jesus, Christian (communities), and Christianity, respectively. These themes can be regarded as what the museum considered to be the starting point to introduce to the readers the knowledge of Christianity. These three themes reoccur and become the themes of different clauses in this panel: Jesus (C1, C6, C10, C11, C12, C13), Christians (C2, C4, C5, C8, C9), and Christianity (C3, C7). In terms of the discursive-epistemic strategies used, this panel mainly features exposition, with typical linguistic features such as the being verb followed by definitions (e.g. ‘collectively called the Church’), identifications (e.g. ‘was and is the Messiah’), attributes (e.g. ‘one of the world’s largest religions’), and the use of figures and numbers (e.g. ‘more than two billion followers’).

It is noteworthy that after Jesus, Christian practice, and Christian traditions are defined, characterised, and identified, the last section of the panel (Clauses 8–13) is similar to the panel at SMM. Clause 8 defines the term Christians, and Clause 9 presents an argument from the perspective of Christians (they proclaim), and the following extension of knowledge about Jesus is framed as the inner experience of Christians. The two panels differ in that in MWR, Jesus and Christianity are already established as given information before the inner experience of Christians with them is presented; whereas in SMM, the inner experience of Christians is the only new information provided to the visitors.

To summarise, SMM considers Christians as the starting point of presenting knowledge of Christianity, and frames all the discussion as inner experiences of Christians. The new knowledge is mainly extended through a chronological narration of the doings of Jesus, resembling a story. In MWR, Jesus as the sayer of the Bible (verbiage) serves as the evidential foundation from whereupon develops the knowledge of Christianity. The panel does not follow a chronological order, but is divided into three elements of religion: the sacred (Jesus), the followers (Christians), and the rituals (Christian practices/traditions). The new knowledge is mainly extended through defining, identifying, and presenting attributes. In the next section, we will explore how this information interacts with the artefacts in the adjacent display cases.

4.3. The display case of Christianity

In both museums, the textual panel on Christianity is placed on the left side of a large display case. This physical location also seems to suggest that the textual panel on the left is existing knowledge, and this knowledge is extended by the visual display on the right.

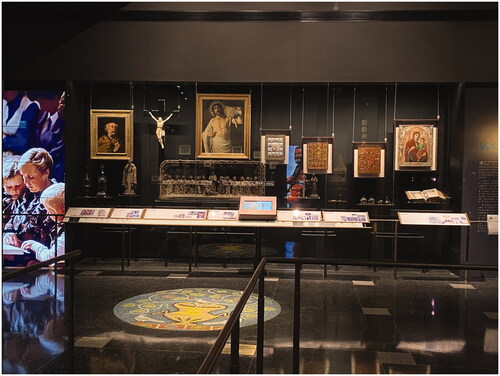

The display case of Christianity in MWR () contains 19 objects, including paintings, sculptures, and a number of items used in religious rituals and ceremonies. Each item is accompanied by a label. All labels follow the convention of museum labels by mentioning the title of the item, and identifying the material and time of production, followed by brief information about the displayed item. The labels provide information about how the objects symbolise Christianity, rather than describing or contextualising the objects.

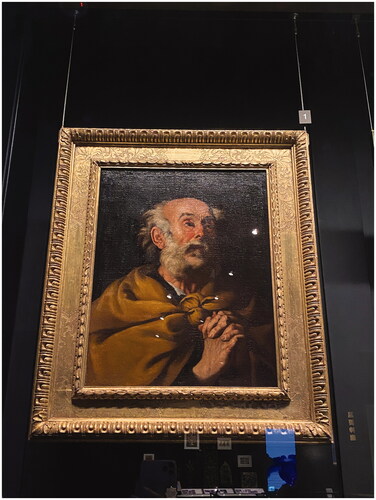

The first object in the display case, starting on the left, is a portrait (). The label title Saint Peter gives identity to this figure, and the subsequent information follows the discursive-epistemic strategy of exposition by identifying and giving attributes to this figure, mentioning that his original name was Simon; he was the leader of the twelve apostles of Jesus, and the first pope of the Roman Catholic Church. The label makes no reference to the spatial dimension of the artefact nor comments on its aesthetic value or significance. In fact, the label does not even make specific reference to the object, by using conventional linguistic devices such as this painting or this portrait, as commonly seen in museum labels. It introduces Saint Peter as an important figure of Christianity, rather than the figure being painted in the picture. Therefore, in contrast with the typical function of labels in museum displays that guide the visitors to look more closely at the artefact, in this case, it is more like the object is an illustration of the textual information in the label.

Figure 2. (photo taken by the author) 聖伯多祿 Head of Saint Peter. Leader of the Apostles 油畫 Oil Painting 西元十七世紀 17th century 聖伯多祿, 本名西門, 為耶穌的十二使徒之首, 在耶穌遇難後, 擔起耶路撒冷教會的重責, 成為羅馬天主教會的第一位教宗。

This is also true for the visual-verbal interaction between the textual panel and the entire display case; that is, the visual items illustrate the thematic panel on Christianity. This painting of Saint Peter, for example, extends the knowledge of Christianity, through the means of a different mode (pictorial, rather than written), by identifying and visualising a key figure in Christianity. The selection of the objects to be displayed in the case also places an emphasis on extending knowledge of Christian rituals, as is obvious from the inclusion of objects titled Monstrance, Ciborium, Chalice, Byzantine Cross, Rosary, Pyx, and Ampulla. Furthermore, these objects are not displayed as individual items, but represent all other items of the kind, and the labels focus on when and how these items are used by Christians, to illustrate Christian practices and traditions. Therefore, we can categorise the logico-semantic relation between the display case, the textual panel, and the label as elaboration (Bateman Citation2014, 196), that is, to identify and to exemplify.

In SMM, the display case contains eight objects. On the top are three Alabaster carvings under the title Christ’s story, and are labelled (from left to right) as Annunciation, Crucifixion, and Resurrection. The three carvings in the temporal sequence echo the narration in the textual panel. The middle of the display case is divided into two halves. The left side displays objects related to Catholic worship and includes a silver-gilt and a silver ciborium, both of which are used for the celebration of the Eucharist, an important ritual in the practice of the Christian religion. The right side has items representing Protestant worship and includes a Church of Scotland pewter communion cup and a wooden bread plate. At the bottom of the display case are a painting of Christ and a Bible.

Unlike the display case in MWR, where the objects function as illustrations of the structured information in the textual panel, the display case in SMM features minimal verbal interpretations. Though the wall at the back of the display case has some written words, the verbal interpretations do not follow the conventional style of labels and the one-to-one link between the labels and objects is not made explicit.

The wide range of objects goes beyond the information in the relatively short textual panel. With little written information about them, the objects interact directly with the visitors through their visual impact and rely on the visitors’ existing knowledge. In terms of the logico-semantic relation, these objects function to enhance the discussion of religion as a phenomenon sensed by religious communities by providing contextual information, such as objects collected by an epistemic community like the Christians in Glasgow. These objects in the exhibition case contribute to the social construction of knowledge in a different manner (sensory, aesthetic, interactive with the overall spatial features).

5. Multimodal sites of religious education

Orzech (Citation2020, 69) argues that ‘each museum of religion or museum display of religion is in effect a material definition of “religion”’. Following this argument, we can conclude from our case studies of the two museums that they have each defined religion in their own ways, reflecting their different aims, in the different epistemic communities in which the museums are situated. What emerges from our systemic textual analysis are two ways of conceptualising religions, as discussed in McGuire (Citation2008). In SMM, religion is construed as practice-based, that is, ‘the actual experience of religious persons’ (McGuire Citation2008, 12). Consistent with the textual analysis is the selection of the objects that may inspire visitors through their aesthetic attractions, and the museums’ focus on displaying what religious believers have actually experienced in their lives, such as persecution and conflicts related to religions. On the other hand, religion in MWR is construed as belief-based, that is ‘the prescribed religion of institutionally-defined beliefs and practices’ (McGuire Citation2008, 12). The textual panel on Christianity clearly reflects a preoccupation with scriptures, and the display case includes objects mainly related to religious ceremonies and rituals. Furthermore, in other gallery rooms, videos and quotes from influential religious leaders (including Pope John Paul II and Mother Teresa of Calcutta) play an important role in asserting authority. Such different definitions construed in the two intersemiotic sites of religious education can be understood from a variety of social, historical, and cultural factors.

In SMM, through the recognition of the long-standing sectarian rivalry between Roman Catholics and Protestants, as well as the religions brought in by the new immigrants, the aim is to promote mutual understanding between people of different or no religions. The museum does not attempt to play an authoritative role in explaining or even teaching the visitors the knowledge of religion. As pointed out earlier, knowledge can be seen as how a society responds to the symbolic system in its environment (Von Stuckrad Citation2013, 8). In SMM, knowledge of religion is developed through the lens of the religious believers (as the sensors) and is constructed as their experience (as a phenomenon). Such development of information and construction of knowledge may avoid potential dispute over the different interpretations of religion in the museum, since religion is defined as individual experience.

Even when views of religious professionals, such as a Catholic priest, are presented, they are not presented as unchallengeable teachings from a religious authority. For instance, in a panel on birth and childhood, a quote next to the photograph of a priest reads: ‘Father Paul Monney (Christian) — I would be mighty disappointed if I was allocated a cloud, given a harp, and had to go away and sing for the rest of my puff. […] I am so looking forward to knowing the God I have spent my entire life trying to get to know by way of preparing…’. In the quote, the first personal pronoun I and the mental process of sensing, such as disappointed and looking forward to, emphasize that this is an inner experience of one individual.

With this emphasis on individual experience and engagement with the supernatural, material objects in the museum are displayed as items that inspire visitors. Their aesthetic and historical or cultural significance is explained, but not solely as symbols of a particular religion. In a way, visitors are given the freedom as well as the responsibility to make connections with these artefacts by themselves – as religious objects, or as a piece of art or an ethnographic object.

MWR, on the other hand, aims to educate people about different religions to enable them to choose a religion that may be the most suitable for them. The museum’s authority in educating the public is endorsed by its collaboration with the Harvard Divinity School. Besides, compared with Glasgow, religion has been a less sensitive topic to discuss in Taiwan. In other words, a very different belief is presupposed in the public discourse in this epistemic community. Compared with the SMM, MWR exerts a stronger cognitive control over how visitors should access the display. The statement of the aim presupposes that there is an accurate way of understanding religions, and visitors come here to learn about religions that they have no previous knowledge of, in order to make the best decision for themselves.Footnote4 The underlying assumption here is that everyone should be religious, and the museum is helping the visitors to choose a religion for themselves.

6. Conclusion

This study demonstrates that verbal interpretation plays an important role in co-constructing the knowledge of religion within a three-dimensional intersemiotic space and within a particular epistemic community with presupposed religious beliefs in its social environment. The analysis has illustrated how the value of material objects is framed through multiple layers of verbal interpretations. Neather (Citation2008, 219) states that a museum is ‘a complex semiotic environment in which a number of different systems of signification interact to produce meaning’. The interaction can be intrasemiotic, such as the arrangement of objects in the same display case, in different cases, and in gallery rooms; or the interaction between different verbal interpretations, such as between the text panel on Christianity and the various labels of Christian objects in the adjacent display case. Or, it can be intersemiotic, such as a verbal-visual interaction. Our analysis has shown that through the design of information progression at the micro-level of grammatical choices, to the macro-level curatorial decisions of what artefacts are to be included, a material definition of religion is constructed in each museum, and that each semiotic mode simultaneously supports and constrains the interpretation of other semiotic modes. Ad-hoc comments on labels or verbal interpretations in the museum, or seeing the verbal and visual as competitive modes, do not help to understand the process of knowledge construction and information development in the museum space. In museums of world religions a systemic approach to analyse verbal interpretations along with the visual objects is essential to uncovering how a material definition of religion is achieved, and how visitors are encouraged to engage with the religious objects.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Min-Hsiu Liao

Dr Min-Hsiu Liao is a lecturer at the School of Social Sciences, Heriot-Watt University. Her research interests are in cross-cultural and multimodal communication in museums and heritage sites. She is particularly interested in examining how different semiotic modes co-construct meaning in exhibitions, and the potential impact on visitors’ experience. Her research has been widely published in academic journals including Museum and Society, Tourism Management, East Asian Journal of Popular Culture, and Translation Spaces.

Notes

1 Although Orzech (Citation2020, 3) suggested replacing the term World Religions Museums with Comparative Religion Museums as a more accurate term to describe museums that display more than one religion, he eventually opted for world religions because this term has become a readily recognised term in this discipline. This study chose the term world religions for the same reason as Orzech, and also because the term is used in the selected museums in our case study.

2 In both museums, the text panels are multilingual. SMM covers five languages: English, Arabic, Gaelic, Mandarin Chinese, and Urdu, while MWR has text panels in English and Mandarin Chinese. For the theme-rheme analysis, we compared the English texts from both panels, not only to ensure consistency, but also because the theme-rheme pattern is developed based on the grammatical system in English.

3 The labels only provide English translation of the main headings. The English translation of this passage is as follows: Saint Peter, whose original name was Simon, was the first of the twelve apostles. After Jesus' death, he assumed the responsibility of the Church in Jerusalem, and became the first pope of the Roman Catholic Church [our translation].

4 To some extent, the different approaches to religion in the two museums can be seen as a reflection of how ‘learning’ is perceived differently in the UK and in Taiwan. In East Asia, education is often perceived as being taught accurate answers, or at least it is very much led by an instructor, with the paths of learning outlined in detailed content and coverage; whereas in the UK, independent learning and critical thinking are highly valued (Loh, Raymond, Teo Citation2017, 197). The education system forms a part of the infrastructure (Von Stuckrad Citation2013, 15) through which the social construction of knowledge is developed in the two museums.

References

- Arthur, Chris. 2000. “Exhibiting the Sacred.” In Godly Things: Museums, Objects and Religion, edited by Crispin Paine, 1–27. London: Leicester University Press.

- Bateman, John A. 2014. Text and Image: A Critical Introduction to the Visual/Verbal Divide. London: Routledge.

- Berns, Steph. 2015. “Sacred Entanglements: Studying Interactions between Visitors, Objects and Religion in the Museum.” PhD diss., University of Kent.

- Blunden, Jennifer. 2020. “Adding ‘Something More’ to Looking: The Interaction of Artefact, Verbiage and Visitor in Museum Exhibitions.” Visual Communication 19 (1): 45–71. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1470357217741938.

- Buggeln, Gretchen T. 2012. “Museum Space and the Experience of the Sacred.” Material Religion 8 (1): 30–50. doi:https://doi.org/10.2752/175183412X13286288797854.

- Carnegie, Elizabeth. 2009. “Catalysts for Change? Museums of Religion in a Pluralist Society.” Journal of Management, Spirituality & Religion 6 (2): 157–169. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14766080902819058.

- Catalani, Anna. 2004. “Objects of Religion’ Exhibition: Interpreting the Yoruba Intangible Heritage from a Western Perspective.” Journal of Museum Ethnography 16: 9–18.

- Clifton, James. 2007. “Truly a Worship Experience? Christian Art in Secular Museums.” RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics 52 (1): 107–115. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/RESv52n1ms20167746.

- Coxall, Helen. 1994. “Museum Text as Mediated Message.” In The Educational Role of the Museum, edited by Eilean Hooper-Greenhill, 132–139. London: Routledge.

- Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly, and Kim Hermanson. 1995. “Intrinsic Motivation in Museums: Why Does One Want to Learn?.” In Public Institutions for Personal Learning: Establishing a Research Agenda, edited by John H. Falk and Lynn D. Dierking, 67–77. Washington, DC: American Association of Museums.

- Da Silva, Neysela. 2010. “Religious Displays: An Observational Study with a Focus on the Horniman Museum.” Material Religion 6 (2): 166–191. doi:https://doi.org/10.2752/175183410X12731403772878.

- Durkheim, Émile. 1915. The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life: A Study in Religious Sociology. Translated by Joseph Ward Swain. London: Georgy Allen & Unwin.

- Eggins, Suzanne. 2004. Introduction to Systemic Functional Linguistics. London: Continuum.

- Foucault, Michel. 1981. “The Order of Discourse.” In Untying the Text: A Post-Structuralist Reader, edited by Robert Young, 48–78. Boston: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Halliday, Michael, and Christian Matthiessen. 2004. An Introduction to Functional Grammar. London: Routledge.

- Knott, Jonathan. 2019. “Tristram Hunt ‘Not Interested’ in V&A Prayer Room.” Arts Professional. Accessed 9 March 2021. https://www.artsprofessional.co.uk/news/tristram-hunt-not-interested-va-prayer-room

- Liao, Ching-Ju. 2006. “宗教文物蒐藏:神聖與博物館化 [Religious Object Collection: Sacredness and Museumification.” Museology Quarterly 20 (2): 67–80.

- Lidchi, Henrietta. 1997. “The Poetics and Politics of Exhibiting Other Cultures.” In Representation: Cultural Representation and Signifying Practices, edited by Stuart Hall, 151–220. London: SAGE Publication.

- Loh, Chee Yen Raymond., and Teck Choon Teo. 2017. “Understanding Asian Students Learning Styles, Cultural Influence and Learning Strategies.” Journal of Education & Social Policy 7 (1): 194–210.

- Martinec, Radan, and Andrew Salway. 2005. “A System for Image-Text Relations in New (and Old) Media.” Visual Communication 4 (3): 337–371. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1470357205055928.

- McGlone, Matthew S. 2005. “Contextomy: The Art of Quoting out of Context.” Media.” Culture & Society 27 (4): 511–522. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443705053974.

- McGuire, Meredith B. 2008. Lived Religion: Faith and Practice in Everyday Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Neather, Robert. 2008. “Translating Tea: On the Semiotics of Interlingual Practice in the Hong Kong Museum of Tea Ware.” Meta 53 (1): 218–240. doi:https://doi.org/10.7202/017984ar.

- O’Neil, Mark. 2006. “Museums and Identity in Glasgow.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 12 (1): 29–48.

- Orzech, Charles. 2020. Museums of World Religions: Displaying the Divine, Shaping Cultures. Location: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Paine, Crispin. 2013. Religious Objects in Museums: Private Lives and Public Duties. London: Bloomsbury.

- Ravelli, Louise. 2006. Museum Texts: Communication Framework. London: Routledge.

- Van Dijk, Teun A., and Encarna Atienza. 2011. “Knowledge and Discourse in Secondary School Social Science Textbooks.” Discourse Studies 13 (1): 93–118. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445610387738.

- Vergo, Peter. ed. 1989. The New Museology. London: Reaktion Books.

- Von Stuckrad, Kocku. 2013. “Discursive Study of Religion: Approaches, Definitions, Implications.” Method & Theory in the Study of Religion 25 (1): 5–25. doi:https://doi.org/10.1163/15700682-12341253.

- Wray, Brad, ed. 2002. Knowledge and Inquiry: Readings in Epistemology. Ontario: Broadview Press.