Abstract

The pandemic has caused social relations to emerge as the leading players in our lives. This translation of a chapter from the book Dopo la pandemia. Rigenerare la società con le relazioni [After the pandemic: Regenerating society with relations] explores the differences between interpersonal relations and role relations, showing the insufficiency of Modernity’s understanding of the social fabric. It describes the acceleration of digitalization and its consequences on social relations, assessing the long-term challenges and showing that it is necessary to build up a new culture of relations that make for a good life.

1. The epiphany of social relations

The Covid-19 pandemic has dramatically shown us the importance of social relations. Without relations, the virus does not exist; it does not exist as a social fact. Perhaps it could exist in the world of pure physical nature, on a planet with no human beings, but we can never know that, because of the simple fact that we would not be in that world.

Since human persons cannot live without relations with other human beings, they must deal with the virus in/with/through relations. In other words, they must confront it within relations, in conjunction with relations, and through relations. This means that relations matter immensely: indeed, they are critical for life. They matter more than money because money cannot buy healthy relations amid the virus. Good health is only obtained with good relations. The category of relation questions us at our very foundations (Sodi and Clavell Citation2012).

The novelty presented by the pandemic is therefore the ‘revelation’ that social relations are a vital element of our lives: no more or less vital to us than air. And like air, relations are also invisible. We only notice them when they cause problems for us. Hence the fact that relations—like air—always represent a risk. And confronting a risk implies having a certain awareness of it and making decisions that always have some level of uncertainty.

Life, illness, and even death, depend on relations. We can therefore refer to an ‘epiphany’ of relationality: relations were ‘revealed’ even though it was not possible to observe them directly. Everyone has had to notice that relations are there, but who can see them? The term epiphany derives from the ancient Greek verb ἐπιφαίνω, epifàino (which means ‘I make manifest’) and from the related feminine noun ἐπιφάνεια, epifàneia (manifestation, appearance, coming, divine presence). I believe that the term epiphany applies very well to what has taken place. Social relations have suddenly emerged as the leading players in our lives. They have manifested themselves as critical for our personal destiny and for that of the entire global population.

If one wanted to understand how there can be a spirit that hovers over the whole world and permeates every corner of the earth, even the smallest and most hidden, then the virus has given us concrete proof that this possibility is real. One of Gabrielle Bossis’ thoughts in her ‘dialoghi con Gesù’ (dialogues with Jesus) comes to mind: ‘Do you know what we’re doing in writing these pages? We’re removing the false idea that this intimate life of the soul is possible only for the religious in the cloister. In reality, my secret and tender love is for every human being living in the world’ (Bossis Citation2019, 293). To understand the pandemic is to understand that this possibility is real.

But what are these social relations which we cannot see, and which modernity has increasingly come to treat as pawns in an endless game? Modernity has worked to liberate people from natural relations, substituting them with artificial relations. By making them artificial, it has made them malleable and transformable at the whims of individuals. It has considered them as pure cultural products, treating them as if they were simple projections of the ego, as the result of subjective feelings and emotions. And this is where it meets its defeat.

There are many examples of the ways in which postmodern culture has come to toy with relations. We can think about how sexual and gender relations are treated, how we toy with creating new relations through tools of artificial reproduction, genetic engineering, and even surrogacy. We can also consider how relations are casually treated in the media and on social media, not to mention the wide world of consumption and fashions, which are, in essence, ways of redefining relations with others.

The pandemic has called everyone to dramatically rethink these artificial ways of understanding and toying with relations. It has confronted us with the fact that relations are a reality that is much more meaningful, important, and challenging to deal with than we think. Their reality is rooted in biology, it is expressed on the psychological level, it involves social bonds, it contains cultural models of value, and finally, it represents the main way we connect with the supernatural. For a Christian, relations are the imprint of the Trinity on all of creation. Playing with this reality as if it were at the disposal of our will, that is, as if we could configure relations to our use and consumption, means setting ourselves up for the greatest of failures.

The pandemic has highlighted the tragedy of modernity, in its ultimate outcomes, and as a way of life and social organization. We have had to acknowledge that if modernity has been able to function until now, then it is because it relied on social relations that have not fully conformed to the values and principles that modernity itself proclaims. For example: the economy has survived because, when necessary, it was able to pursue a minimum of common good outside of the individualistic and competitive rules of the market; political democracy has remained standing because it is based on certain values and human rights imported from (predominantly Christian) tradition, which it was still unable to guarantee; informal relations in the life-worlds have maintained a certain robustness because they have remained anchored to values with a religious background that modernity, however, did not legitimize.

Faced with the impotence of healthcare systems and having to deal with a dramatic economic crisis brought on by the pandemic, the model of society guided by the so-called processes of modernization has proved to be a failure, or at least has proved unable to recover. The world will not be the same after the pandemic. But what will it look like? What are the scenarios that lie before us?

The analysis of the processes and proposals that I shall give here are not meant to get into the merits of health, economic, political-administrative, etc. reform projects, but rather are meant to focus on the dynamics of social relations as a key theme for understanding the problems of the human condition after the pandemic.

2. How the pandemic has changed human relations

2.1. The phenomenology of relations

Let us briefly examine the phenomenology of social relations as they manifested themselves during the pandemic.

People were told that they needed to give up hugging, touching, and meeting in person. They were not told how to re-frame their relationships. They simply needed to practice ‘distancing’ and communicate with others through digital tools, such as the internet, various platforms, apps, and all the tools that fall under into the category of information and communication technologies (ICT).

The message was: if you are not careful in relationships, that is, if you do not keep your distance from others, then you risk getting sick. Physical distancing has been generalized. It has affected the family, school, and workplace, as well as communal and public spaces.

Let us briefly consider some of these phenomena.

(a) Families have been confined to their homes, which has severed inter-generational ties as well as those of kinship, friendship, and neighborhood relations.

The pandemic has led to a total upheaval of relations. While life before the virus was largely conducted outside the home, after the start of the pandemic everything had to be done in the home. Before, people went to work and brought their children to school, ate lunch outside their homes, went out to play sports and go for walks, to go have fun at the movie theater or to see a play, to cultivate their hobbies, and to participate in civic life. After the advent of the Coronavirus, people have had to work from home and take care of their young children at home; and for older children, they had to be equipped to connect to distance learning for schools and universities. People have had to prepare all their meals at home every day, they have had to follow the information on the rules to follow to avoid contagion at home, and they waited, at home, for help and services that never arrived.

The whole fabric of daily relations was disrupted.

As soon as it became clear that the elderly were the most affected, grandparents were isolated. The required isolation constrained nuclear families to an unprecedented communal life. Some research has revealed families’ capacity to be resilient, that is, to respond to the seclusion in a positive way by strengthening their internal relationships. But this reflected a minority of the population. In fact, we need to remember that in Italy in 2020, 30% of the registered families were composed of only one member, and those with two members accounted for 31%, which means that about 61% of families had two members or fewer. All other families, especially those with children at home, were part of the approximately 39% of households that remained (CISF Citation2020, Table 1, 34). The pandemic continued a process of atomization of individuals and of the fragmentation of families that was already underway due to the process of modernization, and further reinforced it.

In any case, the seclusion of families has produced great inequalities in different families’ abilities to deal with the problems of daily life. Removing the social safety net that is assured by relationships with parents, friends, and neighbors has meant exposing families to stress (tension, discomfort, and anxiety) that has had and will have selective effects in the future: some families have felt and will feel more united, whereas others have broken down or will break down in various ways. This is a topic for future research, which should show how those families who could count on a certain internal relational social capital have been able to avoid greater hardship and poverty, while families that lacked it or were even deprived of it have entered a vicious circle of material and relational deprivation, with all its consequences, documented by mental illness, violence, and hardship of all kinds (on the importance of families’ relational social capital, see CISF Citation2003).

(b) Work was suspended for all freelancers and independent contractors, while a substantial portion of employees resorted to remote work. As with families, this isolation has also meant eliminating interpersonal relationships and foregoing socializing. Experiencing unemployment, being laid off, and risking termination are traumatic experiences that involve the deprivation of a fundamental dimension of a person’s social identity, which is precisely that of work as a social relation (not as a functional performance) that is essential for their humanization.

(c) Schools have simply shut down their educational activities. Children have lost their friends, and all their needs have been heaped on their parents. Where possible, some began the so-called experimentation with distance learning, which especially in southern Italy and for elementary-aged children, soon proved to be a problem for many who were not equipped with the necessary digital devices. By losing their identities as schoolmates, children have also experienced a loss of humanity. Of course, older children and university students were able to deal with the isolation with a greater level of autonomy, but even for them the loss of in-person relationships with classmates and teachers represented a stark loss of the sociality that sustains young people’s identities.

(d) The public spaces of social interaction are deserted. There is no nightlife, no sporting events, no shows, and no walks through the park—even for children. Museums and public libraries are closed. Each individual has felt that another dimension of their identity as a friend, athlete, or citizen was missing. In a certain sense, the lack of these extra-familial relationships has stripped us of the many social identities that each extra-familial belonging brings with it, leaving us alone with ourselves, with only our private identity. However, this identity cannot live a meaningful life if it is disconnected from our social identity. As Giulio Maspero writes in Part II,Footnote1 people have been asked to cross the desert.

These brief remarks, as is well-understood, shed light on how the personal and social identity of every individual is dependent on relations with others, even when they are contentious and fraught. It is precisely in the Ego-Alter confrontation that we mature human competencies. Without a ‘full’ relation with the other, we miss out on opportunities for human growth.

The pandemic has required us to distance ourselves from others, all the while strongly feeling the need to be with others. Professionals missed their colleagues and work environment. Schoolchildren and young people were separated from their peers and teachers and longed to see each other again. Those who were able to participate in distance learning still experienced a certain frustration, because they had to learn that connection via the internet is not a real relationship. Children wanted to be with their grandparents, and grandparents wanted to be with their grandchildren, but they could not. Leaving the house required avoiding neighbors. Coffee shops were closed, and with them, the ritual of drinking coffee with friends. The Christian faithful were prevented from attending Mass and in many cases found that churches were closed. They could of course pray at home, but that required a novel relational consciousness, that is, a consciousness of how to enter into relationship with God even outside of the church and liturgical encounters. A quantum leap was needed to redefine the inner conversation (the inner forum) as relational consciousness. The same thing, obviously, applies to the faithful of all religions. With the lockdown, the people and places that individuals used to frequent suddenly disappeared. The result was a total disorientation in the face of lockdown rules that prevented people’s wants and needs for relations from being met.

The pandemic has therefore shown that relations are the fabric of social life in work, in associations, in families, in hospitals, in religious communities, in retirement homes, and in all activities with others. Relations determine our quality of life and our destiny—for better or for worse. In fact, on one hand social relationships between friends, colleagues, relatives, and neighbors were the vehicle for the virus to spread and led to a worldwide catastrophe. On the other hand, while all of this was happening, we felt these same relations as the indisputable source of our happiness.

How can we live without social relations with those with whom we share our existence? We have an absolute need for relations.

Covid-19 has forced us to take stock of relations, and in certain ways weigh and assess them. People have understood that whether or not they get the virus, they depend on their social relations: in the public sphere and in the private sphere. But how do we measure or evaluate relations when we are told that they are dangerous? Here then is the sticking point. We have realized that we do not know how to evaluate or to see, let alone manage, relations in the broadest sense. We do not have a culture of human and social relations, let alone of those relations which transcend the ordinary things of earth.

The pandemic has taught us that we ought to be able to distinguish between in-person and distance relationships, between good and bad relationships, and between immanent and transcendent relationships. But whoever taught us these distinctions? We need to understand more about the relations of which we speak.

2.2. The profound changes in relations

There are many kinds of relations. It may be helpful to recall a distinction that I believe played a large part in the pandemic: the distinction between interpersonal relations and role relations. The first are inter-human relations, that is, relations between people who interact by seeing each other essentially in their human qualities—for what they are as human beings and not for their performance or the social roles they play. Think, for example, about face-to-face relations in the family and between close friends when they confide in one another.

Relations between social roles, on the other hand, are relations between people who interact with each other based on the tasks and expectations of the social roles they play. This is the case, for example, between colleagues, between pupils and teachers, between a shopkeeper and a customer, or between a doctor and a patient.

Indeed, the pandemic has compelled people to transform their interpersonal relations into role relations.

It is true that these two aspects of relations are often intermingled. And this explains why more often than not, we assimilate them to each other as if they were the same thing. However, relations are said to be ‘familiar’ if and only if they are based on such qualities as affection, closeness, empathy, brotherhood or sisterhood, which put roles on the back burner; if the role prevails over the human aspect, then the familiar dimension vanishes. If we interact with a colleague at work, we are certainly acting with a human person and not a machine. However, in the workplace, as in the public sphere, the general expectation is to treat each other according to our roles.

Generalizing the discussion, we can say the following: When we interact with a family member or close friend, we are people who shed our social role: the relationship is typically I-Thou. Ego and Alter enhance empathy, human affectivity, and all those emotional qualities of communication that Laflamme has highlighted in the micro-relations (Laflamme Citation1995). As Buber says: ‘The primary word I-Thou can be spoken only with the whole being—I become through my relation to the Thou; as I become I, I say Thou. All real living is meeting’ (Buber Citation[1923] 1981). Buber somewhat idealizes this relation (see the comments and criticisms in Donati [Citation2015, 24–26]). He does not consider the social character of the interpersonal relationship, which for him remains a mirroring between a singular I and a singular Thou, in a way that is very similar to how faces relate, according to Lévinas. That is why it is useful to consider the perspective of Romano Guardini, who emphasizes how an encounter (Begegnung) means that two realities collide; ‘an ‘encounter’ properly takes place only when it is man who collides with reality’ (Guardini Citation[1956] 1987).Footnote2

On the other hand, when we interact at work, in the public sphere, in the marketplace, and in public and private institutions, we mainly assume a role, and the relation is regulated accordingly. In principle, the sense of distance—of a certain impartiality—grows to the point of extraneousness. That is why in the social relations between roles, there is always the risk that the relation with the Other will become an I-It relation, that is, that the Other will be reduced to a stereotype, for example, ‘my colleague’, ‘the teacher’, or ‘the doctor’ (on the I-Thou and I-It distinction, see Martin Buber [Citation(1923) 1981, Citation1958]). This implies that we tend to ‘caricature’ the Other instead of seeing him or her in his or her humanity. It can also take place in the family. For example, in a couple where the partners no longer understand each other, and one may tend to caricature the other by attributing to him a stereotype which is that of a social role (calling the other a good-for-nothing, a liar, a cheat, a bum, a criminal, etc.).Footnote3

So the spread of the virus, which impedes physical encounters (encounters with the whole being), has meant a distancing between people that has led to the decrease, or even the elimination, of the spontaneous and immediate I-Thou human relation compared to that of the I-It role. Suddenly, people felt more ‘estranged’ from each other. In this, the pandemic meant a loss of humanization. We all felt that something about us, our humanity, was being repressed and that we could no longer treat the Other in a simple and spontaneous way. We had to keep our distance. In the pandemic, the Other is represented as a potential ‘infector’ and treated as such. People must now see themselves as—potential—infectors and infected. This forces them to take on unusual roles for which they find themselves completely unprepared. Hence the sense of constraint and the loss of humanity that any pandemic brings.

At the same time, however, since many of our social identities (those deriving from external activities like visiting friends, playing sports, going to the gym, cultivating hobbies and recreational activities with others, or participating in a community’s religious rituals) have also fallen away, it is true that an inverse process has also emerged; that is, we have been, so to speak, confined in our most intimate humanity. We have had to come to terms with our deepest I, something that happens much less frequently in so-called ‘normal’ situations. And this as an effect of the new relational context of daily life in which space has been reduced to a small circle around us, and time has been suspended.

Hence an unprecedented existential challenge: that of having to redefine our identity with relations that have been reduced to a minimum or even eliminated. New pedagogical responses were needed to deal with this challenge, but society has not provided them in any way. The Church herself had a hard time responding, except with appeals to follow the authorities’ rules and to continue to pray and to do good works individually or in small groups.

‘Social distancing’ was recommended to individuals, without clarifying the difference between it and physical distancing. Physical distancing is a certain quantity of spatial separation, whereas Social distancing is qualitative and involves a refusal of sociality, which is unavoidable. To reduce sociality to physical distance is to reify the social and erase its human significance. Saying that social relations are nothing other than a physical distance has given us another example of how our society lacks a culture of the ‘social’. We shall elaborate on this difference later.

To evaluate relations and their effects involves much more than simply measuring a physical distance (one meter, two meters, or more) and its effects. Evaluating relations implies an internal and external act that we are not accustomed to because modern culture has not educated us in it. Even most nations have shown this cultural deficiency that is so prevalent today. Suffice it to recall that when the pandemic appeared in all its severity, international relations collapsed. In fact, when Italy was the first in Europe to be hit hard in February of 2020, the other countries immediately abandoned it, thinking that they could save themselves from contagion. As we now know, that was not to be the case. They did not understand that relations between countries also exist, and that none of them could close itself off in splendid isolation. Once again, there was a failure to perceive the pervasiveness and strength of social relations. Every person, as well as every nation or region, has closed in on itself without understanding that a social relation can exist even while maintaining physical distance, if the Other remains for the Ego a partner and a friend to turn to with concrete actions and aid that do not involve a physical contagion.

And thus, the question returns: what are these relations? And how do they work?

3. Understanding social relations beyond modernity

Modernity conceived of relations as a projection of the I, of its feelings, moods, objectives, and intentions. It understood them as the product of the internal consciousness of individuals. The pandemic has upset this view, in that people have had to take note that social relations are not the product of their I. The fact is that social relations have their own dynamic. To understand this reality, we need a relational paradigm of personal and social life (Donati, Malo and Maspero Citation2019). Let us explain.

Interhuman relations are an emergent reality between those who act in them, but they are much more and very different than the contribution that individual agents make to the relation. To understand what an emergent phenomenon is, we can draw an analogy with the formation of water (this is an analogy for explanatory purposes only, just for understanding). The water molecule (H2O) is formed by a combination of hydrogen (H) and oxygen (O) under certain environmental conditions. However, water is not the sum or aggregate of the properties of the two components, but something else. It has qualities and properties all its own, which have nothing to do with those of hydrogen and oxygen.

Turning now to social reality, we can say that when the relation between Ego and Alter has a certain stability (that is, when it is a serious thing and not a momentary exchange), it has many similarities with the formation of a water molecule. When Ego and Alter create a meaningful relation between themselves, what emerges is a social structure (I call it a ‘social molecule’) (Donati Citation2013a, 121–126) that gives them a new identity: a relational identity. The bond decisively influences their life, even if that bond dissolves, because its history is the history of the identity of both the Ego and the Alter that is formed over the course of their interactions.

What comes to mind is the relationship of a couple, a marriage, the relation with sons or daughters, which are all emergent relations. However, this is true of all important relations in people’s lives, like friendship, trust, reciprocity, the ability to team up and collaborate with others as colleagues or as members of an association or community.

We desperately need relations in order to find our identity and to forge a satisfying way of life that can only be achieved by inhabiting a socially appropriate form. It is in this form that we find both our personal identity, in response to the question ‘who am I to me?’, and our social identity, in response to the question ‘who am I to others?’ These identities are different (Donati Citation2019a), but they are united by the fact that people’s humanity is forged by the relations they experience throughout their lives (Malo Citation2010). In fact, humans are marked by their unique relational constitution, which is different from that of all other beings (Donati Citation2019b).

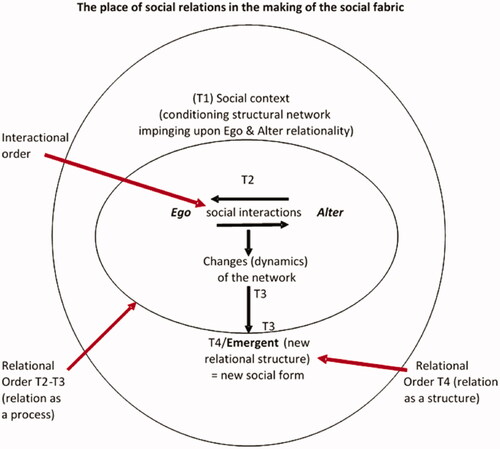

Relations therefore have their own reality which affects the life of every individual. To understand this reality we can refer to a scheme () that shows how Ego and Alter, starting from a certain context in a network that connects them at time T1, interact throughout a temporal phase (T2–T3) of exchanges and transactions (order of interactions as simple events) that generate a social form (structure) between them, which can be a simple reproduction of the initial form (then we speak of morphostasis) or rather an order of reality which I call the ‘order of the relation’ because in it and through it, the social process generates a relational structure endowed with a stability and consistency (which can be, as we said, a reproduction of the initial structure or a new form).

Indeed, the pandemic has caused us to go from social forms made up of ‘total contacts’ between people to a form of social life without contacts, which therefore has not allowed for the formation of social bonds, much less their maturation. Properly speaking, there has been neither morphostasis nor morphogenesis, but simply a collapse of sociality.

Unlike physical and chemical reality, human relations are in fact both a bond (religio) that connects elements in a structure like chemical molecules, and at the same time a reference of symbolic value (refero) that attributes a meaning to the bond and regulates it. The symbolic-referential dimension constitutes the most dynamic element of the transformation of the (meaning of) the bond. Thus, faced with the danger of the pandemic, it was not just a question of wondering whether the bonds between people could survive and then having to realize that they were dying. It was a question of understanding how to maintain the bond by redefining it in its internal intentionality and carrying it out with possible signs and gestures.

Various research studies have highlighted how resilient families have been in the face of the imposed seclusion, resorting to their own internal bonds. However, they did not clarify whether and how people were able to make sense of the changes in their relations, and therefore to redefine bonds in a way that maintained and regenerated their identity in the new context. The fear of Covid has certainly united them. But for how long?

The pandemic has meant suspending and even refusing the formation process from interpersonal interactions, reducing them to distant role relations, drastically impoverishing that vital world (Lebenswelt) from which people derive the primary meaning of their existence.

In light of , let us focus on what happened in the family relations that were at the center of the pandemic debate when national and local governments foisted the problems of daily life on families.

The social context starting at time T1 forced people to shut themselves in their homes. The mantra was ‘Io resto a casa’ (I’m staying home). Therefore, Ego & Alter interactions in temporal phase T2–T3 were confined to homes. For those who lived alone, this meant total isolation and loss of interactions with the outside world. Think of the elderly widows and widowers (widows especially) whose world collapsed around them. Pressure was placed on the relationships of couples as they were unable to tap into their relational networks with parents, friends, colleagues, or social spaces. Those who held up best were families with young children, because the need to care for them brought the parents together. The younger the children, the more parents turned to them as objects of care and play. Families with adolescent children, on the other hand, had more problems, because the adolescent child is more autonomous and more capable of managing digital connections with the outside world, in addition to being in the process of psychologically detaching from his or her parents.

What was the result of these processes?

In temporal phase T2–T3 (see ), blocking and practically eliminating extra-familial personalized interactions forced people to emphasize family interactions. Families withdrew into themselves in different ways. Some families saw greater collaboration between their members, and some couples developed an unexpected cooperative style (psychologists call this dyadic coping). In other couples, however, pre-existing conflicts erupted, as evidenced by an increase in domestic violence and recourse to the police to quell disputes. Other families have been paranoid about disagreements between parents over how to protect their young children. Still other families manifested the so-called ‘sindromo della tana’ (den syndrome), that is, they locked themselves in their homes and were afraid to go out even when the pandemic was receding. China saw an increase in divorces. And in Italy? The birthrate will probably fall in the near future, since potential parents forego having children under conditions of elevated risk and maximum uncertainty about the future. Faced with this kind of situation, there was a need for relational support for parents and children facing hardship, but the welfare system was not designed around relational social work, as is still the case today. This perspective is illustrated by Folgheraiter (Citation2013) in an essay which refers to many other theoretical and operational publications on the subject.

With the sudden disappearance of social networks, the primary instinctive reaction is that of seeking to recover it with digital communication, but then having to realize the communicative poverty of these means compared to interpersonal relationships. This has been the first experience (and a dramatic one at that) of the loss of authentic relationships. Families, deprived of the resource of their networks, have essentially reiterated their stereotypes. There have been those who have shown the face of the (forcibly) happy family that plays with children who are their great consolation, and there have been those who have posted on social media a photo of the couple keeping each other company. Consolatory photographs, which, however, hid the challenges and problems that were not much discussed.

To create an emergent form of the family that represents an innovative way of living, it is necessary that people activate some relational reflexivity. Relational reflexivity consists in having conversations with others about the good of the relation that connects them. It means reflecting on the quality and causal properties of their relation insofar as it involves a common good, a common feeling, an empathetic reaction to emotions, sentiments, and bodily gestures that speak of each other’s state of mind and imagination (Donati Citation2011). This is the only way that members of a family generate those relational goods (Donati Citation2019c), such as trust, mutual giving, and reliance, which generate happiness. However, there was neither the time nor the space to do this. Families were caught in a storm and all they could do was seek shelter and hunker down. How does one reflect on relationships inside and outside the family while standing under a deluge?

However, even in this general situation, there were families who were thinking of others and came up with goals for creative socialization with their communities. We shall call them ‘relational’ families: those who did not let themselves get discouraged by the forced isolation and have prudently and competently established new relational networks, ready to go out safely and offer solidarity to others—the lone elderly, the poor, and immigrants—by shopping for them, bringing them medicine, and offering other small help. Though a minority, we have witnessed families who have been able to create relational goods among themselves and with the community around them.

For most families, however, the forced seclusion has meant experiencing the cultural vacuum of relations that late modernity (also called post-modernity) has reached. It is a culture that I call ‘relationist’ (pragmatist and relativistic), rather than properly relational, because it reduces relations to simple contingent interactions, that is, to flows, exchanges, and transactions that are played out in the interests of the moment without understanding how a happy, or at least decent, social life necessarily requires stable and meaningful relational structures in day-to-day life. It is a culture that conceives of relations as purely eventemential (occasional), and in which relations are thought about and acted upon on a case-by-case basis with no long-term commitment.

People, families, and even organizations that had previously absorbed this type of culture, incapable of pursuing relational goods, found themselves completely disoriented when interactions, fluxes, and material transactions between people came to a halt. They wound up in a relational vacuum as collective social networks collapsed. The desires to return as soon as possible to nightlife, to having a drink with friends, to bacchanal and herd-like behaviors have highlighted the scope of this ‘relationist’ culture that propagates the neo-modernization of society as a new naturalism without a human purpose (for a critical view, see Donati [Citation2013b, Citation2017a]).

It is important to clarify the difference between the ‘relationist culture’ that modernization has come to and a ‘properly relational culture’ of life. They both emphasize relations, but they do so in entirely different ways, and with different consequences.

Relational culture exalts human relations as real entities through which we must pass, in order to explain the meaning of life, because ‘at the beginning is the relation.’ This expression is meant to illustrate that we are born of interpersonal relations and that this gift must be reciprocated. The relational culture of which I speak takes on a position of critical realism, in the sense that it takes note of reality and makes its content out to be problematic, in view of greater humanization. It does not absolutize relations, because relations do not resolve substances, specifically human nature. People are not reducible to their relations, just as relations cannot be deduced from people. Relations are understood according to various orders (layers) of reality; that is, they are multidimensional, horizontal, and vertical, admitting emergence and transcendence.

Relationism, on the other hand, exalts relations in the abstract, constructs them with the imagination, starting from a subjectivist standpoint. Constructivism dissolves the substances, including human nature, into bundles of random relations. Relations are understood as purely horizontal and flat. Their emergence and transcendence are denied.Footnote4

Why is this distinction relevant here? In my view, it is precisely postmodern relationism’s understanding of relations as fluid and random that has been at the root of the behaviors that have led to another wave of Covid infection as soon as attempts were made to get out of the lockdown. Those who denied the reality of relations have also denied the existence and danger of the virus. One group of young people organized a ‘Covid party’ to prove the non-existence of the virus: one of them ended up getting infected and died. There have been many similar cases, and they have mainly affected young people who thought themselves to be most immune from infection—while in reality the median age of those infected fell from about 60 to about 30 years. Episodes such as these may be repeated in the future whenever the relationist perspective prevails, in particular, the perspective of those who have a fatalist and Darwinist view that considers the pandemic as a pure ‘accident’ that results from unavoidable interactions and failures (Perrow Citation1999, 5).

The paradigm of critical and relational realism, in contrast to the relationalists, sustains that social relations are always meaningful and that a healthy life is one that is acted on by the subjects who aim to generate a common good through ‘good’ relations. Where this relational culture is lacking or deficient, the result is that relations are abandoned to pure spontaneity, so that there are those who succeed and those who fail, without being able to say where they are going, as was the case for those who underestimated the importance of relations during the pandemic.

It must certainly be admitted that an appropriate relational culture is much more difficult to achieve than the laissez-faire culture of constructivist relationism. Pitirim Sorokin (Citation[1942] 2010, 28) was already well-aware of this in his time when he recognized that, when confronting disasters and catastrophes, the lack of an appropriate relationality may be considered normal. The effects of the calamities, he writes, do not just involve emotional aspects, like fear, but cognitive processes of representation, memory, imagination, and structuring of thought. Thought becomes paralyzed. The cognitive processes become increasingly focused on the calamity and on the phenomena that are directly and indirectly related to it. Insensitivity (starting with sensation and perception) to elements that are unrelated to the calamity, increases. There is a tendency toward the disintegration of the unity of our ‘I’ and of mental functioning. In fact, the pandemic has shown that people are finding it increasingly difficult to focus on objectives outside of the health situation. In short, Sorokin concludes, calamities promote the growth of mental disorders and disturbances (Citation[1942] 2010, 35).

As Mangone and Zyuzey (Citation2020) observe in reflecting on Sorokin’s perspective, these effects weaken the Self, which tends to become amorphous and does nothing but doubt itself, creating dissonance and different behaviors on the part of the population that is directly or indirectly involved in the disaster. These are behaviors that make it difficult to appropriately address risks, precisely because the subjects lose the ability to rationally calculate risks, let alone to adopt an appropriate strategy.

If I have recalled these sociological analyses, it is to underscore that we need to be aware that such reactions are ‘normal’, and we need to learn to better manage them by recovering a relational and reflexive approach to the situation.

In short, to fight the virus with relational creativity, it is necessary to keep in mind what suggests: we need interactions between people guided by a certain intentionality. If we want to have a society that is securely able to avoid pandemics, then we must regulate the process of interactions in temporal phase T2–T3 (see ) in such a way as to generate ‘good’ relational structures inside and outside of the family, that is, to favor the unity of one’s Self and increase the autonomy of judgment and behavior.

This is why relations are so fundamental for human existence. We saw this during the pandemic, when relations became fraught and dangerous, and therefore needed a surplus of relationality. If we give into fears and herd behavior, then we cut off, suspend, and silence the relations that would instead require a surplus of reflexivity from everyone.

We can draw from this some considerations that would be valid even in non-pandemic times. In fact, every time we treat our relationships poorly, we are treating ourselves poorly. If we toy with relations, we are toying with ourselves. If we do not ask ourselves what meaning and value our relations have, we lose the meaning and value (the dignity) of ourselves.

4. Physical distancing and social distancing

I have already mentioned the need to understand that the reality of the relation is something other than the physical distancing that has been (rightly) recommended to avoid the spread of the virus. Physical distance is only one objective space that measures the separation between two entities, while social distance is a relation, which involves two subjectivities that observe each other and must decide what to do about each other.

To give an example: when celebrating Mass during the pandemic, most priests chose not to say to the faithful at the appointed time, ‘let us offer each other the sign of peace.’ Others, however, continued to tell the faithful ‘let us offer each other the sign of peace’ showing that a sign of peace should also be given with a nod of the head or a wave of the hand, even at a physical distance. The first celebrants reduced social distancing to physical distancing, while the second celebrants distinguished between the two and showed that a sign of peace is not just about shaking hands, but that another action can indicate openness to a social relation.

Two considerations are central for a proper understanding of the difference between physical and social distancing.

A first order of consideration concerns the fact that the pandemic has made us schizophrenic on an existential level because if physical distance is in some way measurable and relatively easy to determine (see the proxemics of Hall [Citation1966])Footnote5 then social distance is not, given that it is primarily a moral quality and not merely a spatial quantity.

What disrupted, more or less unconsciously, the world of relations we had before the pandemic is the inversion of the human rule par excellence: that of ‘making oneself close.’ The most beautiful and unique quality of ‘being human’ in life is that of going to meet the Other, of ‘making ourselves close’, in the sense of experiencing common humanity and the joy that comes from taking care of the Other. The pandemic has imposed the opposite rule: ‘you must move away from the other.’ Which means: ‘save yourself, because the Other might endanger you.’ At this point, we asked ourselves: should we give up our humanity? That would be a catastrophe. It is then a matter of understanding that physical distance cannot cancel out human social distance. One can always be close to the Other, one can always take care of the Other. What we must do is find other ways of doing this than the material ways of physical contact. These ways will be more spiritual and less ‘physical’, even if the flesh has to be there, since we are not angels or celestial beings, which means that we have to make the body relational as well. We must manage the body in such a way that it can relate to the Other with feelings and gestures, but also with whatever material help is possible while still being safe from contagion.

A second order of considerations is the fact that, to overcome the aforementioned schizophrenic experience brought on by the virus and thus reach greater relational wisdom, we need a moral action that rises above mere physicality.

We must learn to see and evaluate relations, not only as a physical distance, but as a reality that is endowed with moral qualities and causal properties sui generis. Relation implies ethical choices and may cause life or death. Knowing when to keep the proper distance between Self and Other, to involve ourselves and detach ourselves, to bring into play all of our humanity and our existence. Faced with other epidemics of a social rather than biological nature (for example, of racial hatred, of so-called post-truth, and of different kinds of denialism) it is not the physical distance from others (racists, peddlers of fake news, deniers of crimes against humanity) that saves, but the fact of being able to take the right distance from them. The right distance means knowing to differentiate the person from the error, a task which requires relational reflexivity both towards the person, so as not to reduce him or her to a thing, and toward the error that spreads. Here too, this is about seeking opportunities to create relational goods.

Take the case of one relational good that proved crucial during the pandemic: trust. When the psychological climate in a certain context is such that ‘everyone is a potential infector’, giving and receiving trust is a challenge for everyone. In the family restricted only to those in the household, distrust can be overcome by a sense of obligation toward other members and by love. However, if we are referring to external relations, with people or with institutions, things get much more complicated.

Belardinelli and Gili (Citation2020) have analyzed the processes of trust and distrust in interpersonal relationships and toward institutions (the national health service, hospitals, and national and local governments) during the pandemic. They started from the assumption that trust is given based on credibility, and then they distinguished analytically between believing things said by others and believing in those who said them. The two forms are closely connected because, if there is an information asymmetry (that is, the subject is not able to have sufficient information to evaluate what is said to him) then there is nothing left but to believe in whoever (the person or institution) asks for trust, with all the uncertainty of the case.

Belardinelli and Gili suggest differentiating between the forms of trust in reference to the subject toward whom the expectation of trust is directed, that is, to the subject perceived as credible, be it a person or an institution. Intersecting the interpersonal and institutional characters of relations with the specific or general dimension, they derive four different forms of trust on which the epidemiological emergency has had a significant impact. The four forms are as follows.

Specific interpersonal trust is directed toward specific individual subjects. Indeed, Covid-19 has profoundly modified trust in many close relationships. This included, first of all, family members of the sick in home therapy: in these cases, people were kept completely separate in order to prevent spread to other family members (for example, by confining the sick person to another room when possible). The same thing happened to doctors and healthcare workers who came into closest contact with the sick: it was recommended that they keep a safe distance from their family members, so much so that some hospitals even rented apartments and hotels to house the most directly involved healthcare personnel. The most dramatic aspect was the separation of the sick, especially the elderly in hospitals and sheltered facilities, from their families who were unable to visit them, which created a sense of abandonment and disorientation.

When it came to generalized institutional trust, that is, general trust in others or in ‘people,’ it too is now in crisis, and attempts have been made to address it with technological tools, such as apps (like Immuni) that track routes and interactions with other people to map risks of contagion (who, what, where), or bracelets that sound when there is ‘wrong’ or careless behavior, and other technological devices that monitor or contain the risk of (misused) liberties from others: devices such as drones, cameras, and robots in streets and public places.

Specific institutional trust is directed toward particular institutions and is related to the perceptions that individuals—like clients, users, or citizens—have of those institutions. During the pandemic, trust in doctors and nurses grew as a specific trust but also as a generalized institutional trust, while the institutions of the overall healthcare organization that had to provide the various devices (masks, pads, beds, etc.) were the subject of increasing distrust.

Overall, Italians’ trust in institutions of the political-administrative system that was to govern the exit from the pandemic (which was already very low) has further diminished.

The same can be said for generalized institutional trust, or systemic trust, that is, the overall trust in the Italian system’s capacity to deal with the epidemic and the economic crisis that ensued, along with the inability of the political system to give adequate proof of its competence and action.

In conclusion, trust has collapsed during the pandemic. To restore it, it is necessary to promote an increase in personal and social ‘reflexivity.’ Personal reflexivity concerns the internal conversation in which the individual constantly examines himself (or herself) and contemplates for himself what to do (what is right to do) in relation to his own ends, but also to the characteristics, constraints, and opportunities of the context in which he acts. Social reflexivity on the other hand is that which is exercised on the relations between people and between collective subjects to evaluate the effects that the relations qua tales have on the identities of the subjects, because only giving an ethical direction to the relations can extend forms of trust and social solidarity (Donati Citation2011, 31 ff., 295–298). For this reason, the solution to the crisis of trust lies in once again focusing attention and public discourse on the individual and collective ‘reasons’ for giving and receiving trust, values, and the ultimate ends of acting in society.

5. The limitations of the ideas for addressing the pandemic and opportunities for transcendence

How did society respond to the pandemic?

Ideas for getting out of the epidemic crisis and its economic consequences were marked by the notion of returning to pre-Covid conditions as much as possible, as quickly as possible. The mantra that the world would never be the same was repeated over and over, only for people to regret having lost something. This was—as it will be in the future—not a matter of restoring the previous conditions and continuing along the same path of self-referential modernity, but of radically changing our relations with other human beings, the environment, nature, cultural goods, the arts, science, and the visible and invisible world. Here, ‘changing’ means redefining relations in a way that is not appropriative, manipulative, egocentric and competitive, and not for use or consumption ad libitum, but a recognition of and respect for the Other, be it a person, physical nature, or another living being, in the reciprocity of the goods in play.

During the pandemic, most people gave up their own desires and passions only because they were compelled by public regulations. They gritted their teeth in anticipation of going back to doing the things they used to do. The desire to get out and have fun like before is certainly understandable. But when a person’s desire is not reflective and well-considered, when it is not organized in a way that leads to living a life of good relations but is only an expression of more or less instinctual impulses, then it is clear that this person has not learned anything from the pandemic. Modern culture does not help, because it only values success, showing off, and seeking others’ consensus with the consumption of status; basically, displaying one’s importance in a more or less narcissistic way. Meanwhile, we need relational goods. This is where modern culture shows its incapacity, impotence, and sterility for dealing with systemic crises like the pandemic, and for dealing with the subsequent economic and existential crises.

In general, all the ideas for overcoming the pandemic have been healthcare- or economics-related and did not ask what impact such solutions might have on human and social relations. Naturally, we must distinguish between institutions and various actors in civil society. However, analyzing this complex picture is beyond the scope of this essay.

Nevertheless, we can say that the vast majority of these actors reacted by trying to point out paths toward a return to pre-pandemic ‘normalcy’ based on the lietmotif of the story: the revitalization of the modernization process with more human skills and more technology to reform societal institutions. The refrain has been substantially technocratic, in the sense that the solutions to the problems have been geared toward greater efficiency of institutions, including the healthcare system, and above all, toward the accelerated adoption of all kinds of large-scale new technologies (digital networks, artificial intelligence, robotics, 5 G, etc.) to revitalize the economy and all societal systems. We have witnessed a sort of ‘compulsion to repeat’ the patterns of the modern conception of progress.

This conception is based on what I would call the ‘salvation formula’ of modernity, centered around the dyad: ‘human mind + technology.’ The formula consists in increasing the capacities—especially the mental capacities—of human subjects (human enhancement) combined with an increasingly rapid and widespread use of new technologies.

It is basically this formula which has been applied to every sector of society, from public administration to the economy, from healthcare systems to schools, and from businesses to families. All these actors and all these ideas have failed to grasp the importance of social relations.

They did not think in terms of relations. They have remained prisoners of non-relational or a-relational thinking. The formula ‘human mind + technology’ may be attractive, but it has the enormous defect of ignoring the social aspect. Great managers, technocrats, the business world, and those bent on innovation to succeed and make money love it; however, it is of no use in addressing the phenomenon of epidemics since it remains prisoner to the modernist paradigm.

To overcome these crises, we need a new cultural paradigm, a ‘cultural matrix’ that does not only consider the human mind and technology, but also touches the social realm, that is, the world of relations, which is of an ontological and existential order.

By cultural matrix I mean the models of value that guide our relational life. These models depend on the theological foundation that justifies them, or in any case, that makes them credible and the source of meaningful action.

To summarize very briefly, the cultural matrix inherited from modernity has a theological foundation that proposes an individualist and subjectivist view of ultimate values. Consequently, it is ill-equipped to overcome the defects that have emerged as a result of the pandemic, because we need a cultural matrix that has the category of relation as its central and indispensable concept.

This leap is a civilizational leap. It has characteristics of what Max Weber, studying civilizational changes, would call a ‘process of cultural breakthrough’ (Donati Citation2010a), that is, a radical redefinition of the ultimate meaning of life and of the human condition which transcends the value categories of the present.

The pandemic offers such an opportunity if we consider it as a historic turning point that requires us to get at the roots of problems. The cultural breakthrough occurs when it appears clear that we are at a dilemmic crossroads: either go back to the previous path and face failure, or decisively change course, regenerating the cultural roots. So-called sustainable development, the circular economy, the Green Deal, the fight against poverty and inequality, etc., sound like empty goals if they are not sustained by a new relational cultural matrix. The thought of achieving these goals with a project of technological neo-modernization (5 G, artificial intelligence, robotics, etc.), is laughable.

The collapse of social relations, both as bonds in social support networks and in the loss of trust between persons and in institutions, cannot be dealt with just by thinking about ‘re-establishing’ a presumed lost normalcy by revitalizing technological tools as the means of rebuilding. It requires a cultural and organizational development that can transcend the cultural limits of the pre-existing conditions of the pandemic. In other words, it requires a conception of social relations that is not physical in essence, but spiritual—even if this spiritual conception is connected to the human body, which it certainly cannot do without.

Christianity still has much to tell us when it says that our identity and life are based on a relation of divine filiation. In this relation we find an answer for how to manage relations when they cannot be ‘physical’ but only ‘social’, in the sense that they connect people regardless of physical presence. It is therefore the prototype of vital relations that ground people’s humanization.

This means that we need a theological matrix for which substance and relation are implied as co-principles of reality (Maspero Citation2013). Only this kind of theological matrix can sustain a culture and an operational paradigm that can overcome our enormous deficits in dealing with social relations (Donati Citation2010b). Giulio Maspero gives an account of this in the second part of this book.

6. The pandemic has accelerated the digitalization of society

Many have observed that during the pandemic, there was a great deal of online sharing of information, messages, and conversations. Of course, it is all to show that these connections have strengthened the culture of relations. They have certainly been a step forward in the technological literacy of individuals and families, which in Italy was far behind such digital giants as China, Japan, South Korea, the United States, and others.

Remote work, distance learning, services requested on the internet, etc., did more in a few weeks to train families for the digital world than anything else had over many years. However, some might argue that this is another step toward the surveillance and colonization of the population. Then the question returns of what social relations we need in order to not be colonized by the great Digital Matrix that governs our world and will increasingly permeate it. I am using the term Digital Matrix to refer to the pervasive environment of the digital (virtual) reality in which humanity is destined to live—in a way that is increasingly distant from its natural matrix (Donati Citation2021c).

The Digital Technological Matrix can be defined as the globalized symbolic code that regulates the creation of technologies designed to improve or substitute human action. By modifying human action, digital technology conditions the human persons who use it, to the point that the Digital Matrix changes their identity along with the social relations that constitute them (since identity and social relations are co-constitutive). As the symbolic reference code, this Matrix tends to substitute all ontological, ideal, and moral symbolic matrices that have structured societies in the past. In a certain sense, the Digital Matrix I am talking about is a functional substitute of that metaphysical conception delineated by Leibniz, in his Dialogus (1677). Leibniz says that ‘the world is formed by the thought and calculation of God’ (cum Deus calculat et cogitationem exercet fit mundus). The Digital Matrix takes the place of God. The great calculator is no longer the divine person, and certainly not the human person, but an anonymous system that encircles and permeates the world.

Scholars now ask: can this calculating form of the world, which is of course created by human intelligence, also become a human form of life? Is there a certain criterion for speaking of the human that precedes or exceeds its constructs? Or are these constructs what in turn determine what is human? These questions do not currently have an answer, and that is because once again, the inalienable substance (the non-reducible exceptionalism) of the human condition, which is its relational specificity, is removed. If one does not see in relationality—ontologically understood as reciprocal action endowed with a supra-functional meaning—the unique and original character of what constitutes the human being (Donati Citation2019b), then everything remains uncertain and indeterminate, and it is in indetermination that every individual’s dependence on the Digital Matrix grows.

The increasing digitalization of human and social relations involves their transformation (morphogenesis) which we can call hybridization (Donati Citation2017b). If the interactions between Ego and Alter (as in above) are purely digital, then the emerging social form will also be ‘virtual’.

On the contrary, the social forms, created by concrete and analogical social relations (insofar as they are invisible), have their own reality that is anything but virtual. They are a little like dark matter in the physical world. We cannot see dark matter with the same tools we use to see visible matter or with other electromagnetic tools, because dark matter is composed of particles that neither absorb, reflect, nor emit light. It is matter that cannot be directly observed but has a significant gravitational pull. We know it is matter that exists because of the effects it has on objects we can directly observe. We could also say the same thing about social relations we do not see: we see their effects, not their substance.

Communications through digital media are a bit like ‘dark relations’. They hide the contexts in which relations take place: relations that we cannot see with the naked eye or with direct tools, but that affect the ones communicating. Their reality can only be grasped through the influence they have on many people and on the world. The analogy with dark matter is instructive. Just as we can measure the energy (dark energy) that depends on dark matter, it may be possible at least in principle to measure the effects (the energy) on the social sphere which are to be attributed to relations. In the physical world, we know that dark matter makes up about 27% of all matter in the universe and that about 68% of the universe is dark energy. The rest (all that has been observed on earth with the tools available, that is, all visible matter) makes up less than 5% of the universe. And in the social world?

In a certain sense, dark relations form the vast majority of the relations of which we can have some awareness. The pandemic has had the effect of accelerating the digitalization of society, and with it, the quantity of dark relations. It has done so in remote work, in distance learning, in household services purchased online, and generally in the acquisition of information and things that once required a human or social relation.

The digitalization of society produces relations that are characterized by attraction and repulsion just like dark matter in the universe: the use of digital communications is attractive because it replaces the lack of face-to-face physical relations (the phenomenon of attraction), but at the same time, using digital media gives us a sense of emptiness because they lack physicality and do not give us the sensory perception of the other with whom we are communicating (the phenomenon of repulsion).

During the pandemic, everyone had to get up to speed on the use of technology, especially ICTs, apps, platforms, and understanding more about how algorithms and artificial intelligence work. The pandemic has been an unbelievable push to enter more fully into the infosphere that Floridi (Citation2014) speaks of. Technology is changing and will continue to radically alter our relations, because social and human relations will increasingly be mediated by digital technology. Plenty of good can come of this, but also plenty of evil if the technologies are used without an adequate culture of relations.

In fact, since the relation can never entirely be mediated by the subjects that constitute it, it always needs a ‘Third Party’ that mediates it. The Third Party, in short, is the inter between the subjects that is made necessary by the non-mediatable opening—which is intrinsic to the relation—which leads to an Other with respect to the individual terms of the relation. This is a question of seeing whether this Third Party has the characteristics of the human (i.e. is a moral good), or is instead constituted by a technological means. The relation maintains a human character only if the Third Party that carries out the mediation is a moral good, which cannot be replaced by a mere technological tool, just as it cannot be produced by the self-awareness of the subjects in relation. This moral good consists in the otherness that is reciprocally established between the subjects of the relation. It must be understood through the meaning it has, that of reciprocal co-constitution between Ego and Alter, and in general between the subjects of the relation. This is the only way for the human aspect to be retained and to thrive.

So that the mediation of the relation is not left entirely to technology, it is necessary to give greater power and capacity to people so that they do not become the terminals of a technocratic system that monitors everyone and conditions them towards more or less unspoken goals. However, this cannot take place if the structural—social and cultural—context that conditions people’s reflexivity is not changed (I am referring to the starting context in ).

In this territory, the two leading models in the world—the authoritarian regime of China and the market-based American democracy—do not bode well. We know very well that a society conceived as a market, like the United States, leads to widespread anomie (lack of shared moral norms) and creates a society of more or less alienated individuals. In China, on the other hand, the pandemic has been the occasion for the strengthening of an authoritarian political regime (the enemy of human rights) that has seized the opportunity to control the healthcare sphere in order to reinforce dictatorial social control. From now on, all Chinese, even though there are about a billion and a half of them, will be subject to the surveillance of an unprecedented technological apparatus, which will follow them 24 hours per day to know all their actions. Even today, each Chinese citizen is assigned a ‘social code’ that consists of a score that measures the degree of the individual’s compliance with the directives of the public authorities. In the case of compliance, the score will increase, with resulting benefits; otherwise, the score will be reduced, and those who fall below a certain threshold will be denied fundamental freedoms. In blatant violation of human rights, this will create different classes of citizens, with a mass of people considered to have no citizenship rights, that is, considered non-citizens.

Most of the world will be squeezed between these two giants that will utilize digital technologies to affect people’s lives with penetrating tools, albeit in different ways. The Coronavirus has helped a great deal to move the world in this direction.

It becomes urgent that we understand how the new technologies influence human and social relations and what we can do to avoid giving in to their overwhelming power, which is that of techno-capitalism.

7. The consequences of digitalization on social relations

In every corner of society, the use of new media technologies (communicative and informative, artificial intelligence, robots, etc.) is revolutionizing the previous ways of living and, therefore, the social relations that constituted them.

Let us take the case of work. Remote work (also called teleworking, or in Italy, smart working) has increased in our country from 500,000 people to 8 million people in a few weeks. It is called ‘flexible’ work, but in truth it is only flexible for the most creative jobs. The question is: will it become more widespread, and will it be permanent? It is crucial to answer this question, because if this type of work has some advantages, it has a major disadvantage: in most occupations it eliminates socialization and prevents people from seeing work as relation, reducing it to a simple functional performance with no social context. For most professional occupations, going to work and working with others means meeting people, socializing, and exchanging many things that make people friends. Being at home, all contacts are lost, and relations are reduced to digital connections. The scenario is problematic, especially if we consider that the large multinationals which operate in and with the digital reality (such as Disney) have announced that they will convert all their positions into remote work.

We have yet to understand what it means to bring work back into the home. Max Weber (Citation1968) rightly noted that the modern world was born out of the separation of home and business. Bringing business into the family is another sign of the end of modernity as we have known it in the past two centuries. The new relationality that mixes family and work involves configuring society in a way that modifies all daily relations, inside and outside of the family, thus merging work time and family time. If we then add distance learning for children, we can understand very well how much weight falls on the lives of people at home.

As for the spread of distance learning for schools and universities, we can expect that it will have unforeseen consequences on the socialization of younger generations. Indeed, we need to consider that education consists primarily in an interpersonal relationship between the teacher and the student, which goes far beyond the transmission of informational content. Moreover, the use of distance learning technology to educate young people leads to great social inequalities, because students have unequal access to such technology, depending on the different levels of their families’ availability and on differences between school structures in different regions (urban and rural areas, north and south, etc.).

There is a growing risk that the machinery of the digitalization of relations will overtake the human subject. We are once again confronted with a danger that many authors (Marx, Weber, Simmel, and Heidegger) feared back in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, namely, that the technological products that humans have created could again descend on people and make them increasingly alien to themselves. Today this danger is even more serious, because the new technologies are endowed with far greater autonomy and intelligence than those of the past.

How should we react? In my view, we must adopt the ‘relational gaze’ (Donati Citation2019d, Citation2021a); that is, we must observe reality as a relation and adopt courses of action that, following a genuine practical interest, are interested in evaluating things from the standpoint of how human relations impact our existence.

Piero Migliarese (Citation2020) provides an example of this line of reasoning regarding the organization of work. He suggests that we rethink interconnections between tasks and workers based on the type of relations they involve. There are simple tasks that require ‘soft bonds’, that is, generic bonds, limited to information and communication. There are also tasks that can only be carried out after another job has been completed, and therefore strong sequential bonds exist between them. Finally, there are bonds between even more strongly interacting tasks, such as design, that require strong reciprocal bonds between participants.

In the case of soft bonds, tasks are separable, and many can even be automated. In the case of sequential bonds, tasks can be separated within an agreed upon or assigned timeframe. In the case of reciprocal bonds, on the other hand, tasks are inherently unpredictable and difficult to separate. They therefore require close, continuous, and complex proximity. Spatial proximity requires strong interactions, and so technology must take a backseat, since this deals with human creativity. The use of technology can replace repetitive and automatable work, but it cannot replace work as a human relation that requires close interdependence between people in sharing physical space and necessary time.

We can distinguish the ways different technologies (communications technology, artificial intelligence, sociotechnical systems) mediate social relations (it may be useful to consult Sawatzky [Citation2013]). More sophisticated artificial intelligence, since it is capable of autonomous interactions, is more difficult to master than the means of simple communication, and it has a more significant effect on people’s minds. Sociotechnical systems are a blend of technology and social relations in which we need to address the hybridization of human relations and their consequences.

The most relevant phenomenon, in my opinion, is that with the spread of new technology, relations have fallen prey to interactive communication. Relation is only that which is communicated and at the moment in which it is communicated. This is what most communication theories say. According to these theories, relations do not exist outside of interactive and technologically mediated communication (that is, they do not ex-ist, in the sense that there is no reality outside of communication). This assumption of communicative constructivism makes two major errors.

The first is the error that relation precedes communication, and not the other way around. In short, communication always takes place in a relational context. To ignore this fact is to preclude a significant part of the understanding of the message. According to Knoblauch (Citation2019), ‘society exists in the temporal continuation of sequences of communicative action.’ This comes up a little short, in my opinion, because society is the context in which communications take place. The pandemic has revealed that fact, since communicating has primarily meant placing oneself in the context of relation with others.

The second error of communicative constructivism is that of justifying and nurturing the relativism of relations, because this reduces the relation to communication, thus making it completely contingent. Those, such as the above-cited Knoblauch, who theorize the passage from social constructivism to communicative constructivism, are then forced to remedy the relativism that follows by appealing to reflexivity on communication (‘it is the reflexive insight in the relativity of knowledge which allows us to escape relativism’ [Knoblauch Citation2011, 151]). Reflexivity on communication is necessary but insufficient, however, because once deprived of the relational context, communicative reflexivity falls prey to the paradoxes of ‘communication about communication’ (as in Niklas Luhmann): communication turns in on itself.

Reflexivity is important, but reflexivity of individual communicative actions is not enough. It must become relational reflexivity, that is, it must be exercised on the interpersonal and social relation to avoid relativism. Reflecting on the relation, rather than on oneself (on one’s own thoughts), leads one to consider the actual reality rather than just the products of the mind. Only then can one avoid the constructivist fallacy of those who, like Luhmann, say that ‘reality is my observation’ (Luhmann Citation1990) meaning that reality is a construction of my mind.Footnote6 No, the reality of the relation is not what I think of it, it is something else. This exact error has led many to underestimate the existence of the virus and its power to spread, especially in such countries as the UK, the USA, and Brazil.

8. The educational and creative role of relations