Abstract

The paper examines the rhetorical imagination of the Catholic speaker in public discourse on the basis of the parliamentary discourses of Pope Benedict XVI. According to this researcher, Pope Benedict XVI’s rhetorical model in the speeches is an extended version of Michael J. Hostetler’s critical distance model supported by the translation idea of Jurgen Habermas. This conclusion is reached by analysis of the constituent elements of the arguments in three parliamentary speeches given by Pope Benedict XVI. James B. Freeman’s updated version of Stephen Toulmin’s argumentation model is used to discern the constituent element of the argument.

1. Introduction

The public discourse of a Catholic leader is more challenging than ever in a post secular society. Today, the pope, bishops, bishops’ conferences, priests and Catholic communicators have to address the public (the secular audience) in various situations and on different platforms. A preacher cannot predict under what circumstances or in what media his speech will be discussed and what effect his speech will have. If a Catholic leader were to use ecclesiastical or religious language, it would not be helpful in building a bridge to the secular audience. For best results, a religious speaker should always make use of rhetorical imagination in his public speech.

The decline of religious faith, the expansion of the universe of unbelief and agnosticism, the lifestyle associated with technological progress, relativism and secularization, all these have affected people’s thought patterns and their national conversations. Globalization, the influx of immigrants and an increasingly pluralistic vision have also contributed to this change in mentality. This does not mean that religion and religious discourses have lost their importance, but only confirms the fact that the conditions of faith have changed in comparison with previous times. The discourse of a religious leader must take into account all these changes.

2. Public discourses of Pope Benedict XVI

Pope Benedict XVI contributed much to the public conversation with his extensive corpus of public speeches. Throughout his pontificate, he was invited to dialogue with political, civic, academic, and cultural authorities. His contributions revealed a remarkable sensitivity to the fundamental problems of man and his relationship with society. He expressed man’s quest for transcendence and the need for a universal moral order. His reflections on relativism, the meaning of freedom, and the foundation of law were significant in terms of the public sphere. Above all, the pursuit of solidarity, respect for a pluralistic faith, and his intellectual legacy led me to select his public speeches for a qualitative study.Footnote1 I selected three of his parliamentary speeches. First, the Bundestag speech that Benedict XVI delivered during his apostolic visit to Germany (2011); second, the speech at Westminster during his tour of the United Kingdom (2010); and third, the speech at the United Nations headquarters (2008).

3. Religion in public conversation and the idea of critical distance

The study evolved around a central question. What should be the rhetorical imagination of a Catholic speaker in the public sphere?

There is a direct answer to this question from American communications expert Michael HostetlerFootnote2 (Edwards and Weiss Citation2011). At the Eastern Communication Association International Conference in 2012, he proposed the critical distance model for analysing religious discourse in the public sphere. According to Hostetler, ‘critical distance is defined as an act of rhetorical imagination that creates a space where both speaker and audience may critique and interrogate the comprehensive world view of the speaker’ (Hostetler, Citation2013). Here the speaker and his belief are under ‘suspicion’ and the speaker must defend on what authority he speaks about the subject.

To answer the above-mentioned internal dilemma (of the speaker and of his belief), Hostetler cites two other communication experts, David TracyFootnote3 and Michael J. Perry.Footnote4 Usually, religious writers find it difficult to distance themselves from their own belief, especially in their moral arguments. However, David Tracy argues that religious hermeneutics, like a relationship with a close friend, requires a trust powerful enough to risk itself in critique and suspicion, and continues that this critique can be done only on the basis of powerful trust in one’s own belief, not because of one’s weak faith (1987, 112). In Tracy’s own words:

The interpretations of believers, will, of course, be grounded in some fundamental trust and loyalty to the ultimate Reality both disclosed and concealed in one’s own religious tradition. But fundamental trust, as any experience of friendship can teach, is not immune to criticism or suspicion. A religious person will ordinarily fashion some hermeneutics of trust, even one of friendship and love, for the religious classics of her or his tradition. But as genuine understanding of friendship shows, friendship often demands both critique and suspicion […] A friendship that never includes critique and even, when appropriate, suspicion, is a friendship barely removed from the polite and wary communication of strangers. (Tracy Citation1987, 112)

Most fundamentally, deliberative democracy affirms the need to justify decisions made by citizens and their representatives. Both are expected to justify the laws they would impose on one another. In a democracy, leaders should therefore give reasons for their decisions, and respond to the reasons that citizens give in return. But not all issues, all the time, require deliberation. Deliberative democracy makes room for many other forms of decision making as long as the use of these forms themselves is justified at some point in a deliberative process. Its first and most important characteristic, then is its reason-giving requirement. (Gutmann and Denny Citation2004, 3)

In deliberative democracy people should be treated as not merely objects of legislation but as autonomous agents who take part in the governance of their society, directly or through their representatives. Another characteristic of deliberative democracy is that the reason given for decisions should be accessible to all the citizens affected by the decision. Citizens often have to rely on experts. This does not mean that the reasons, or the basis for the decisions, are inaccessible (Gutmann and Denny Citation2004, 3–5). Perry infers that a religious conversation in public is a kind of giving reason for the belief of the speaker with the listeners responding to the ‘reason’ in return.

In support of his concept critical distance, Hostetler adds Ronald C. Arnett’sFootnote5 ‘interspace’. Ronald C. Arnett describes ‘interspace’ as a space between persons in public in which relationships occur, permitting creativity and difference to be driving forces within the public domain. A healthy public sphere demands the preservation and protection of the ‘interspace’. Features of the ‘interspace’ as follows:

1. Interspace between persons – reclaiming distance that modernity falsely suggested could be bypassed. 2. Freedom and creativity that dwells in the between of those interspaces. 3. Friendship that is nourished by those interspaces, even when one may not personally like another; and 4. A reclaiming of common sense that obligates us to know what we do not like or approve of in order to engage the other and keep the public domain healthy. (Arnett Citation2013, 195–6)

When a religious person speaks in public, whether he intends to or not, he may gain that critical distance which is an act of imagination or state of mind observable to critics. According to Hostetler’s analysis of three major American speeches, conditional sentences, descriptive sentences, and humour will help to accomplish critical distance. But at the same time, he welcomes other approaches or models for acquiring it (Hostetler Citation2013, 77–89).

4. Pope Benedict XVI and an extended version of critical distance

I considered using Michael Hostetler’s critical distance model to analyse Pope Benedict’s speeches, but Hostetler’s approach of critical distance is difficult to fully apply in this case because Pope Benedict’s discourse did not rely much on conditional sentences, descriptive phrases and humour. However, as Hostetler welcomes other possibilities of acquiring critical distance model, an idea mentioned in a dialogue between Jurgen Habermas and Joseph Ratzinger (Ratzinger and Habermas Citation2006) helped me to conceive the hypothesis upon which to proceed, one that builds on the basic ideas of Hostetler (that is, that critical distance is as an act of rhetorical imagination that creates space in which both speaker and audience can critique and question the speaker’s comprehensive world view).

In the dialogue with Ratzinger, Habermas refers to the importance of religious tradition and its influence in the public square and criticises attempts to silence religious conversations in the public sphere. According to him, market and the power of bureaucracy are destroying social solidarity in the postmodern period. The coordination of action based on values, norms and a vocabulary intended to promote mutual understanding (Ratzinger and Habermas Citation2006, Part 1, ch. 4, para. 3). Thus, it is in the interest of the constitutional state to deal carefully with all cultural sources that nourish its citizens’ consciousness of norms, and their solidarity. ‘When secularized citizens act in their role as citizens of the state, they must not deny in principle that religious images of the world have the potential to express truth. Nor must they refuse their believing fellow citizens the right to make contributions in a religious language to public debates (Ratzinger and Habermas Citation2006, Part 1, ch. 5, para. 4).

According to Habermas, religion can do a lot in the above-mentioned context by translating religious values into secular idioms. Habermas considers the transmission of a religious voice in public by citing an example from the book of Genesis:

One such translation that salvages the substance of a term is the translation of the concept of ‘man in the image of God’ into that of the identical dignity of all men that deserves unconditional respect. This goes beyond the borders of one particular religious fellowship and makes the substance of biblical concepts accessible to a general public that also includes those who have other faiths and those who have none. (Ratzinger and Habermas Citation2006, Part 1, ch. 4, para. 2)

I think Benedict’s model of argumentation follows this model and can also be seen as a remote application of Hostetler’s critical distance, or in other words, that Pope Benedict uses the translation model to gain critical distance (Jose Citation2023, 86–87). This study, then, explores how Habermas’s idea of translation can be seen in Pope Benedict XVI’s speeches, bringing about Hostetler’s critical distance.

5. Analysis of the pope’s speeches using James B. Freeman’s argumentation model

The next interesting phase of the study is to know whether Pope Benedict follows the new extended version of the critical distance model. In order to reach a conclusion on the point, one must get to the constituent element of the claims in the speeches. Constituent elements give an idea about the features of a claim, and the feature indicates whether it translates the religious content into secular terms.

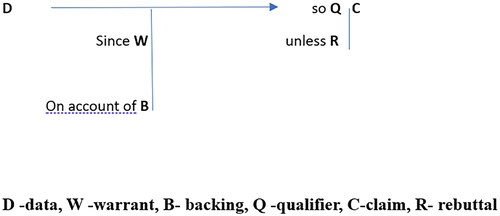

How can one find the constituent elements of a claim in the speech? Here we need another methodology. I prefer James B. Freeman’sFootnote6 updated version of Stephan Toulmin’sFootnote7 argumentation model (Freeman Citation2005a, 77–89). It gives a comprehensive picture of claims or arguments. explains the dynamics of argumentation (Toulmin Citation2003, 97).

Freeman’s model indicates that there should be data or information for every claim, supported by warrants and backing. Warrants are hypothetical or logical statements which act as bridges between claims and data. They can be implicit or explicit rules, inferences or principles. They are just like proofs presented in juridical courts. Backing means other assurances without which warrants have no authority. Warrants are also something inferred from backings. In some cases, there will be a qualifier which indicates under what circumstances arguments/claims are true. Conditions of rebuttal indicate under what circumstances the general authority of a warrant would have to be set aside.

There are four kinds of warrants, according to Freeman’s study (Freeman Citation2005b, 114–269). They are: necessary, empirical, institutional and evaluative. Necessary warrants are self-evident, logical, conceptually true statements. Empirical warrants are empirically discerned causal connections. Institutional warrants are discerned from interpretative sentences which are developed through explanation. Evaluative warrants are discerned by value judgments. It is very important in the study to discern the kinds of warrants most used by Pope Benedict XVI, and especially the percentage of the different kinds of warrants. Since warrants play a key role in the belief mechanism, the warrants used can tell something about the nature of the speeches and thus the rhetorical imagination of the speaker in general.

5.1. Model workshop of the analysis by Freeman’s argumentation model

Here we have a have model workshop as to how Freeman’s model applies to a speech of Pope Benedict (Jose Citation2023, 346–349), using a small paragraph from his parliamentary address in the UK:

Religion, in other words, is not a problem for legislators to solve, but a vital contributor to the national conversation. In this light, I cannot but voice my concern at the increasing marginalization of religion, particularly of Christianity, that is taking place in some quarters, even in nations which place a great emphasis on tolerance. There are those who would advocate that the voice of religion be silenced, or at least relegated to the purely private sphere. There are those who argue that the public celebration of festivals such as Christmas should be discouraged, in the questionable belief that it might somehow offend those of other religions or none. And there are those who argue – paradoxically with the intention of eliminating discrimination – that Christians in public roles should be required at times to act against their conscience. These are worrying signs of a failure to appreciate not only the rights of believers to freedom of conscience and freedom of religion, but also the legitimate role of religion in the public square. I would invite all of you, therefore, within your respective spheres of influence, to seek ways of promoting and encouraging dialogue between faith and reason at every level of national life. (Benedict XVI Citation2010)

1. In some places public celebration of Christmas was discouraged in order not to offend other religions.

2. Christians who work in public services are asked to act against their conscience.

This information indicated in the speech comes from real incidents in the UK. Regarding the first point, there was discouragement of the public celebration of Christmas in 2010 in the city of Luton (Vallely Citation2010). Regarding the second, it is based on the four most debated national cases of religious freedom in the United Kingdom during the period from 1990 to 2010. These cases were: 1. Nadia Eweida (case no. 48420/10); 2. Shirley Chaplin (case no. 59842/10); 3. Lillian Ladele (case no. 51671/10); 4. And Gary McFarlane (case no.36516/10) (Puppinck, Citation2013). The two above-mentioned pieces of data are considered as backings. And one can infer something from these two backings: there are signs of failure in preservation of rights of religious freedom in the UK. Article 9 of the Human Rights act 1998 in UK offers religious freedom (Morgan Citation2017), and since it is a law, it can be considered an institutional warrant. This helps us to form the following argument.

Argument: Legitimate rights of believers are at risk in United Kingdom, and this is against the constitution of the state.

Warrant: Article 9. human rights act 1998 (institutional)

Backing: Discouragements of public celebration (empirical)

Backing: 4 famous cases of religious freedom in the UK (empirical)

6. Relevant results of the analysis

Analysis of the three speeches has rendered interesting results about the constituent elements of the of the arguments and hence Pope Benedict’s own model of critical distance (Jose Citation2023, 246–479). Here I summarise some of the major findings and observations under seven headings.

6.1. Distribution of warrants in the arguments and its significance

The analysis has identified 42 arguments in the three selected discourses of Benedict XVI (Jose Citation2023, 460). Out of these 42 arguments, 13 (30.95%) arguments are supported by necessary warrants (i.e. logical or conceptually true statements), and 5 (11.90%) arguments are supported by empirical warrants (warrants that are experientially known). That means in the analysis almost half of the total warrants (18 out of 42) are logical and experiential. The presence of necessary warrants and empirical warrants in the speech renders a higher communicative result. There remain 24 warrants (57.14%), and these fall under the heading of institutional warrants. They are laws or rules or doctrines related with different institutions. In the selected speeches they are linked with United Nations instructions (Benedict XVI Citation2008), the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Benedict XVI Citation2008), United Kingdom Parliament laws (Benedict XVI Citation2010) and Catholic doctrines. Most of those warrants are known to the audience. If they are known to the audience, their reliability is comparatively high according to Freeman (Citation2005b, 114–269).

As a religious head, it was enough for Pope Benedict to use only pure Christian institutional warrants for arguments as part of fidelity to the doctrines of the Church. But he selected something from the intellectual tradition of the Church – natural law – with which everyone can connect. Putting credence in the fact that human reason has the capacity to know what is true and just, Benedict XVI designed his arguments on this basis. He tried to demonstrate natural law and its implications with the help of logical statements (necessary warrants), with the support of empirical factors from the history and culture (empirical warrants), and with the help of institutional laws that are verifiable to the audience (institutional warrants) (Jose Citation2023, 246–479).

Though the percentage of institutional warrants is high, one doesn’t get the feeling that Pope Benedict used only Christian institutional laws (doctrines) to demonstrate the argument. Because natural reason and natural law are close to the heart of human beings, he was able to use these as a way of connecting to the audience. Or, in other words, these are the instruments by which Pope Benedict tries to open the heart of the audience; he thinks that they have the capacity to transcend religious barriers. At the same time the composite of these three warrants, which serve as evidence for natural law or natural reason, creates a rhetorical space between the audience and the speaker.

The observation about the case warrants is also true about the backings (Jose Citation2023, 461). The analysis derives 83 backings in support of the 42 arguments. 11 out of 83 backings are necessary, 49 out of 83 are empirical, 15 out of 83 are institutional, and 8 out of 83 are evaluational. So the pope did not use only institutional backings – he used all kinds. The percentage of empirical backings is particularly high, which indicates that the audience might have related more to the speech because the backings were experiential or verifiable.

6.2. Common arguments, warrants and backings derived from the three speeches and the inferences

There are 42 arguments in the analysis of three speeches, but we see recurring themes. This has something to say about Benedict XVI’s rhetorical imagination. Here I present those arguments and warrants in order to get a general idea of the Pope’s communication strategy.

The similar arguments have come under six major titles (Jose Citation2023, 447–479). They are: 1. The necessity of a moral foundation for the state (universal moral foundation); 2. majority consensus in making law with regard to the fundamental issues of life (justice is denied when rights are considered purely in terms of legality divorced from ethical and rational dimensions – critique of legal positivism); 3. the capacity of human reason to discern justice and truth (Catholic reason has a role in the ethical foundation of civil discourse); 4. religion has a role in the public sphere; 5. cultural argument; 6. irrational use of science and technology is a fact (critique of positivist understanding of science and reason).

6.2.1. The necessity of moral foundation in a state (universal moral foundation)

A) That which is right, or objective truth about fundamental questions of life, as the foundation of law regarding the fundamental questions of human life, is necessary in a state (Benedict XVI Citation2011).

Warrant: Results of Nuremberg Law in the German history (empirical).

Backing: World wars and the absence of fundamental truth (empirical).

Backing: Scientific experiments that negate human life (empirical).

B) An objective moral basis in civil discourse is necessary for obtaining answers in a moral dilemma (Benedict XVI Citation2010).

Warrant: The relation between the intrinsic value of human person and his existential aspirations demands objective moral foundations (necessary).Footnote8

Backing: Lack of ethical foundations is the reason for global financial crisis (based on studies) (evaluation).

Backing: Christian leaders who believed in natural law tried to stop the slave trade (empirical).

C) In the context of international relations, objective foundations of laws can play an important role in the realisation of a fundamental part of the common good and the safeguarding of human freedom (Benedict XVI Citation2008).

Warrant: If there is no common truth to which people of different backgrounds and culture can appeal, it is difficult to achieve universal common good or fundamental common good (necessary).

Backing: Reason for the formulation of Universal Declaration of Human Rights (empirical).

Backing: Negative effects of globalisation in Africa (empirical).

Natural law, which becomes the implicit warrant in all the three arguments, can be considered as a Christian institutional warrant. The presence of objective moral principles is the major concern in natural law. But Benedict XVI presents natural law in a reasonable way and when he does it, he translates Catholic religious content into secular language. In the backings he takes the historical events and makes a moral evaluation. Anybody can understand the meaning of it.

6.2.2. Majority consensus in making law with regard to the fundamental issues of life (justice is denied when rights are considered purely in terms of legality divorced from ethical and rational dimensions)

A) Majority criterion is not enough when framing laws for the fundamental questions of human life in the state; instead, there should be some absolute principles (Benedict XVI Citation2011).

Warrant: use of authentic human freedom and its relationship with man’s dignity and existence of the word (necessary).

Backing: Net result of Nuremberg law 1935 (empirical).

Backing: Formation of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (empirical).

B) Social consensus as the ethical foundation of civil discourse is a fragile criterion in the democratic process, especially in moral dilemmas or in fundamental issues of human life. An objective moral base is necessary (Benedict XVI Citation2010).

Warrant: Majority consensus has no right to comment on the intrinsic dignity and the existential aspirations of any man (necessary).

Backing: Lack of ethical foundation in the global financial crisis (evaluational).

Backing: History shows that Christian leaders who were inspired by the natural law were able to stop the slave trade (majority opinion did not stop the slave trade) (empirical).

C) The attempts to reinterpret the foundations of human rights according to selective choice run the risk of contradicting the unity of human person and the indivisibility of human rights (Benedict XVI Citation2008).

Warrant: Natural law states the inner relation of the human being to the Creator Spirit and to his fellow beings. His quest for the absolute helps him to flourish fully in the society. These aspirations would be hurt by changing the foundation.

Backing: It is referred to as a “common standard of achievement” in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. It cannot be altered (institutional).

Backing: Victims of hardship and despair whose human dignity will be easy prey to violation (evaluational).

Natural law becomes the common principle behind the three warrants. In the first two, the natural law is stated in a reasonable way. The third one is in an institutional model. The content of the institutional warrant (C) is relatable to all, because there is a quest in human beings to relate to all and to be part of the just society.

Regarding the backings, the first and second arguments are supported by necessary and empirical backings that show the strength of the arguments. These are mainly results of reflections on historical events. The rest is supported by evaluational and institutional backing. But the truth presented will get wider acceptance because it is presented in light of shared concepts.

6.2.3. Capacity of human reason to discern the right things, or truth (Catholic reason has a role in the ethical foundation of civil discourse)

A) Christianity proposes that reason and nature, in their inter-relation, are the true source of law, provided nature and reason are rooted in the creative reason of God (Benedict XVI Citation2011).

Warrant: Man’s participation in the Creator Spirit helps him to recognise the right things regarding the fundamental issues of life, through the inter-relation of nature and reason. What is right can be known without the help of Christian revelation (institutional).

Backing: The United Nations and the Universal Declaration Human Rights are a human reflection of an objective moral foundation (empirical).

Backing: The later argument of legal positivist Hans Kelson, which he made in his old age (as opposed to his earlier and perhaps more famous one) (empirical).

B) Human reason, which is able to discern right action, helps to purify and shed light upon the application of reason to the discovery of objective moral principles (Benedict XVI Citation2010).

Warrant: Human reason is able to recognise what is right. Relation with the Creator Spirit (personal logos) helps do that. What is right can be known without the help of Christian revelation (institutional).

Backing: Reason derived from natural law spurred Christian leaders to stop the slave trade (empirical).

Backing: Pathologies of reason and religion that we experience demand true human reason (evaluation).

C) Universality and indivisibility of human rights are based on our common origin and the rationality of the human being, and we know that this is so based on natural reason (Benedict XVI Citation2008).

Warrant: Common origin of human beings presupposes a common law inscribed in man (necessary).

Backing: The Universal Declaration of Human Rights is accepted on a commonly held sense of justice. If it is only the will of legislators, it can be misused. If it is considered as just a ‘common ground’ it will be minimal in content and weak in effects (necessary).

Backing: Implicit reference on Burma human rights violation in 2008. Variation of meaning of UHRD according to socio- cultural context (empirical).

All the three warrants state, directly or indirectly, natural law. The third one is said in a reasonable manner (necessary warrant). The first two are institutional in nature but the content of the argument implies that man is able to recognise what is right. Benedict XVI believes in a universal experience of man’s inward quest for truth and a just society, and he makes the content of his argument seem reasonable and believable with empirical and necessary backing. Historical incidents and moral evaluation of them strengthen the argument. Nobody can negate this kind of approach. With it, Pope Benedict elevates human reason to a wider dimension.

6.2.4. Religion has a role in the public sphere

A) The inalienable and inviolable rights we see in human rights are the confirmation of the need for an objective truth about human life which is derived from the juridical culture of the West, in which the Jerusalem-Athens-Rome alliance plays a role (Benedict XVI Citation2011).

Warrant: Relation between logos, natural law and Jerusalem-Athens-Rome alliance (institutional).

Backing: Presence of objective moral foundation in Declaration of Human Rights (empirical).

B) The history of sixty-five years of bilateral diplomatic relations between the Holy See and the British government demonstrate that the Catholic Church can make positive contributions in the public sphere (Benedict XVI Citation2010).

Warrant: Bilateral diplomatic relations between Holy See and British government (institutional).

Backing: Shared elements in Catholic Social doctrine and bilateral relations between the British government and Holy See (institutional).

Backing: Shared elements between Catholic social doctrine and parliament traditions of UK (institutional).

C) Religious freedom in a state can contribute to experience of humanity, peace, development and cooperation, and can guarantee rights in the future (Benedict XVI Citation2008).

Warrant: Religious freedom is grounded in man’s transcendental nature, which helps him in his search for God, truth and justice (unity of man). The same nature inherently helps man to develop fully in relation to his fellow human beings in society and to fulfil the aspiration for transcendence. The recognition of this dimension leads to conversion of heart. Conversion contributes to peace, development, cooperation, and the guarantee of future rights (institutional).

Backing: Jerusalem-Athens-Rome alliance and its effect, which we see in the United Nations and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (institutional).

Backing: Special status given to the Holy See by United Nations (empirical).

Natural law becomes the underlying principle of all warrants. All three claims (A, B, C) in this section are supported by institutional warrants. The first and second warrants are generally known to the audience. In those cases, the pope’s references served as a reminder to the audience of something which with they could connect (role of Jerusalem-Athens-Rome cultural alliance in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, shared elements in bilateral diplomatic relations). The third one is related to anthropology, and it may not be fully familiar to the audience. But the backings reinforce the argument to some extent.

6.2.5. Cultural argument based on Jerusalem-Athens-Rome alliance

A) The positivist vision of law and its character of self-exclusivity and negation of other cultural realities does not respect Europe’s cultural memory. True law should respect its cultural legacy (Benedict XVI Citation2011).

Warrant: Natural law and the Jerusalem-Athens-Rome alliance contributed to Western Culture (institutional).

Backing: Historical Relation between Jerusalem-Athens-Rome and Universal Declaration of Human Rights (empirical).

Backing: Pope works out an enthymeme (necessary).

B) Worrying signs of disregard for the rights of believers and freedom of conscience in British society suggest that it is trying to separate itself from its parliamentary democratic heritage and the contribution of the Christian religion (Benedict XVI Citation2010).

Warrant: Traditions and contributions received by the parliament from Christianity (empirical).

Backing: The religious freedom offered in the UK constitution is at risk (institutional).

Backing: Christian iconic personalities in UK who contributed from their religious wisdom (empirical).

C) Removing human rights from the context of natural law would mean restricting their range and yielding to a relativistic conception, according to which the meaning and interpretation of rights could vary, and their universality would be denied in the name of different cultural, political religious outlooks (Benedict XVI Citation2008).

Warrant: Natural law involves the idea that man is in the image of God and thus has dignity; this law is inscribed in human hearts and is therefore present in different cultures and civilizations. If human rights are removed from the context of natural law there will be no universality (institutional).

Backing: variation of meaning of human rights according to socio-political culture is a fact. The human rights issues in Burma in 2008 are implicitly referred to (empirical).

Pope Benedict’s arguments are closely related to the culture, traditions and identity of the society he addresses. He demonstrates the connection between natural law and European culture (first two arguments); in the case of UN speech he relates natural law to juridical culture generally. The first argument has a direct connection with the natural law. The second one has connection with Catholic social doctrine, which has its roots in natural law. In two of the cases, Benedict uses the warrant that is known to the audience (Jerusalem-Athens-Rome alliance with European culture, and UK parliament tradition with Catholic social doctrine). He familiarizes the audience with Catholic content in connection with secular institutions, and hence secures the role and identity of Catholic Church in the public sphere. The United Nations has also received of the same culture (Jerusalem-Athens-Rome cultural alliance and natural law) through the Dominican Friar Francesco de Vitoria. In the UN speech Benedict XVI criticises attempts to change the foundations (which are based on natural law) according to selective choices. He presents backings from relevant sources (human rights declaration, Jerusalem-Athens-Rome alliance, UK parliament tradition, present religious freedom in UK and the constitution, the history of stopping the slave trade in UK, Burma human rights issue etc.). Throughout he maintains an empirical and rational tone, even though he is a religious leader.

6.2.6. Irrational use of science and technology does happen (critique of positivist understanding of nature and reason)

A) Our lost relationship with nature and the consequent eco movements in Germany make us rethink the positivist vision of nature and reason (Benedict XVI Citation2011).

Warrant: Ecological issues demonstrate the defect of the positivist vision of reason and nature (necessary).

Backing: Enthymeme (necessary).

Backing: Hans Kelson’s (legal positivist) shift in the argument (empirical).

B) Even though science and technology have brought outstanding benefits to humanity, environmental problems and the destruction of the sanctity of life show that they are being used irrationally and that science and technology have failed to recognise the authentic image of creation (Benedict XVI Citation2008).

Warrant: Nature and man have inner directives which should not be transgressed. Natural law is the principle behind them. Inner directives of man and nature cannot be discerned by the positivist concept of nature and reason. Ecological problems demonstrate the irrationality of a positivist concept of reason and nature, because true reason does not cause harm.

Backing: International action for environmental protection (empirical).

Backing: Misuse of reason that negates life (empirical).

Pope Benedict uses ecological problems (eco problems are the results of positivistic understanding of reason and nature) as one of the strong backings for his arguments based on natural law in the Reichstag speech and United Nation speech. Both warrants are related to natural law, because natural law states that nature has inner directives. But the positivist understanding of nature and reason cannot recognise the invisible directives of nature. In all three speeches we see reference to misuse of reason or pathologies of reason.

All the arguments that come under the six headings from 6.2.1 to 6.2.6 imply that Pope Benedict considers natural law as a common principle when speaking with public audiences. Natural law is a language that has many aspects and has universal value, so that a Catholic speaker can use it to connect with all. Natural reason plays a major role in communicating religious contents. Pope Benedict refers to the common origin of man (Benedict XVI Citation2008) in the speech which presupposes a common law for all – which we could call natural law. Reference to the United Nations and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights indicates that they share a common language. Both are formed on a commonly held sense of justice, and came about due to recognition of a threat to the existence of the human being. This signifies an invisible common language and ethics. Human reason (natural reason) is able to understand the relationship between the necessity of authentic freedom and the existence of humanity. The nations of the world could agree on the point. Pope Benedict affirms the connection between natural reason and natural law in western cultural memory. Thus, generally he tries to reveal the bond between natural law, human reason, and the Catholic religion – but this ‘natural reason’ can be understood by common people even without the help of revelation.

Pope Benedict reveals different aspects of natural law in historical events, cultural memories, and social phenomena. Different dimensions of natural law are revealed differently through the warrants he gives. The Creatorship of God (Benedict XVI Citation2011, Citation2008), an objective moral foundation (2008; 2010; 2011), limitation to free will (2011), reason opened to transcendence (2011), human dignity (2008), unity of the person (2008) and rationality of faith (2010; 2011) are examples.

6.3. Bridging function of natural law for a pluralistic audience

A decisive feature that evolved from the analysis is that all forty-two arguments are in a way related to natural law or natural reason; thus, we see that Pope Benedict follows Catholic social tradition in his public addresses (Jose Citation2023, 444–446).

Here we have some sample arguments from Pope Benedict’s speeches in support of the following proposal: that which is right, or objective truth about fundamental questions of life, is necessary in a state as the foundation of law on the fundamental questions of human life (Benedict XVI Citation2011):

an objective moral basis is necessary in civil discourse in order to obtain answers in a moral dilemma (Benedict XVI Citation2010);

in the context of international relations, objective foundations of laws can play an important role in the realization of a fundamental part of the common good and the safeguarding of human freedom (Benedict XVI Citation2008);

the majority criterion is not enough when framing laws for the fundamental questions of human life in the state – instead, there should be some absolute principles (Benedict XVI Citation2011);

social consensus as the ethical foundation of civil discourse is a fragile criterion in the democratic process, especially in moral dilemmas or in fundamental issues of human life, and therefore an objective moral base is necessary (Benedict XVI Citation2010);

attempts to reinterpret the foundations of human rights according to selective choice run the risk of contradicting the unity of human person and the indivisibility of human rights (Benedict XVI Citation2008).

All these arguments of Pope Benedict indicate unambiguously the necessity of objective moral foundations for the state which derive from natural law (International Theological Commission Citation2009, nos. 48,51).

Pope Benedict XVI places confidence in human reason. The capacity of human reason and its ability to know the truth and justice is another area of Pope Benedict’s thought that has close connection to natural law (International Theological Commission Citation2009, nos. 48, 50, 51, 56). There are sample arguments:

Christianity proposes that reason and nature, in their inter-relation, are the true source of law provided that nature and reason are rooted in the creative reason of God (Benedict XVI Citation2011);

human reason, which is able to discern right action, helps to purify and shed light upon the application of reason to the discovery of objective moral principles (Benedict XVI Citation2010);

universality and indivisibility of human rights are based on our common origin and the rationality of the human being, and we know that this is so based on natural reason (Benedict XVI Citation2008).

Pope Benedict recognizes the universal human experience of man’s inward quest for truth and a just society which nobody can negate. He is sure that if there is no foundation such as natural law, human rights declarations will be weak in content and minimal in effect.

Pope Benedict has argued upon the basis of the cultural roots of Europe. The culture springing from Jerusalem-Athens-Rome has contributed a lot to the development of the juridical culture of Europe (Ratzinger Citation1988, 228–231). The relation between the juridical culture of the West and the natural law is an historical one (Ratzinger Citation1968, 137–148).

The following are some examples from the speeches:

the concepts of inalienable and inviolable rights that we see in human rights declarations are the confirmation of the need for an objective truth about human life which is derived from the juridical culture of the West, in which the Jerusalem-Athens-Rome alliance plays a role (Benedict XVI Citation2011);

the positivist vision of law and its character of self-exclusivity and negation of other cultural realities does not respect Europe’s cultural memory;

true law should respect its cultural legacy (Benedict XVI Citation2011);

worrying signs of disregard for the rights of believers and freedom of conscience in British society suggest that it is trying to separate itself from its parliamentary democratic heritage and the contribution of the Christian religion (Benedict XVI Citation2010).

Pope Benedict’s arguments are closely related to the culture, traditions, and identity of European society.

Pope Benedict’s critique of the positivist understanding of nature and reason is another area of argument. He demonstrates his objection through modern man’s lost relationship with nature. This is also part of natural law argument. The International Theological Commission observes:

The concept of natural law presupposes the idea that nature is for man the bearer of an ethical message and is an implicit moral norm that human reason actualizes. The vision of the world within which the doctrine of natural law developed and still finds its meaning today, implies therefore the reasoned conviction that there exists a harmony among the three realities: God, man, and nature. In this perspective, the world is perceived as an intelligible whole, unified by the common reference of the beings that compose it to a divine originating principle, to a Logos. (International Theological Commission Citation2009 nos. 69, 81)

This rhetorical imagination plays an important role in the study because of its bridging function in the current pluralistic culture. In Caritas in Veritate Benedict says:

In all cultures there are examples of ethical convergence, some isolated, some interrelated, as an expression of the one human nature, willed by the Creator; the tradition of ethical wisdom knows this as the natural law. This universal moral law provides a sound basis for all cultural, religious and political dialogue, and it ensures that the multi-faceted pluralism of cultural diversity does not detach itself from the common quest for truth, goodness and God. Thus, adherence to the law etched on human hearts is the precondition for all constructive social cooperation. Every culture has burdens from which it must be freed and shadows from which it must emerge. The Christian faith, by becoming incarnate in cultures and at the same time transcending them, can help them grow in universal brotherhood and solidarity, for the advancement of global and community development. (Benedict XVI Citation2009, 59)

6.4. Method of translation and the contents

Pope Benedict XVI’s rhetorical imagination is revealed through the dynamics of his presentation of claims. He generally uses translation. How does he translate religious contents? In some cases, he uses logical statements, enthymemes, or conceptually true statements, which are the major strength and identity of his arguments. Use of enthymeme and conceptually true statements are results of his study, reflection, mastery in different disciplines. For example, he conceals an implicit enthymeme in his Reichstag speech:

We have seen how power became divorced from right, how power opposed right and crushed it, so that the State became an instrument for destroying right – a highly organized band of robbers, capable of threatening the whole world and driving it to the edge of the abyss. To serve right and to fight against the dominion of wrong is and remains the fundamental task of the politician. At a moment in history when man has acquired previously inconceivable power, this task takes on a particular urgency. Man can destroy the world. He can manipulate himself. He can, so to speak, make human beings and he can deny them their humanity. How do we recognize what is right? How can we discern between good and evil, between what is truly right and what may appear right? Even now, Solomon’s request remains the decisive issue facing politicians and politics today. For most of the matters that need to be regulated by law, the support of the majority can serve as a sufficient criterion. Yet it is evident that for the fundamental issues of law, in which the dignity of man and of humanity is at stake, the majority principle is not enough. (Benedict XVI Citation2011)

Majority consensus was the criterion for framing law in Nuremberg in 1935.

Human dignity is not defended by the Nuremberg law.

Human dignity is not defended by majority criterion.

The importance of moral foundation of the law is conveyed through the enthymeme.

There are examples of conceptually true statements: ‘But in and of itself it (positivism) is not a sufficient culture corresponding to the full breadth of the human condition. Where positivist reason considers itself the only sufficient culture and banishes all other cultural realities to the status of subcultures, it di-minishes man, indeed it threatens his humanity’ (Benedict XVI Citation2011).

In some cases, translation is through empirical warrants or experiential warrants. Popular historical events and their reflection are used in those warrants. Pope Benedict makes moral inferences from those warrants which people cannot easily deny. For example, in the address to the United Nations he says:

The principle of ‘responsibility to protect’ was considered by the ancient ius gentium as the foundation of every action taken by those in government with regard to the governed: at the time when the concept of national sovereign States was first developing, the Dominican Friar Francisco de Vitoria, rightly considered as a precursor of the idea of the United Nations, described this responsibility as an aspect of natural reason shared by all nations, and the result of an international order whose task it was to regulate relations between peoples. Now, as then, this principle has to invoke the idea of the person as image of the Creator, the desire for the absolute and the essence of freedom. (Benedict XVI Citation2008)

There are also institutional warrants. The belief mechanism works through institutional laws and explanations. Some institutional warrants are directly related to Catholic theology, anthropology, philosophy, or the constitution of the state or organisation, for example the United Nations and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Some warrants are verifiable to the audience, which increases the reliability of the arguments. For example:

In the first half of that century, the social natural law developed by the Stoic philosophers came into contact with leading teachers of Roman Law. Through this encounter, the juridical culture of the West was born, which was and is of key significance for the juridical culture of mankind. This pre-Christian marriage between law and philosophy opened up the path that led via the Christian Middle Ages and the juridical developments of the Age of Enlightenment all the way to the Declaration of Human Rights and to our German Basic Law of 1949, with which our nation committed itself to 'inviolable and inalienable human rights as the foundation of every human community, and of peace and justice in the world.' (Benedict XVI Citation2011)

6.5. Religious content and its translation in the speeches

For Benedict XVI, religion is a vital contributor in the national conversation. He proposes religious wisdom offering complementary assistance in the public sphere in order to find objective moral principles. Keeping a critical distance by using the translation model, he proposes not purely religious claims, but content based on Catholic religious wisdom. There are some sample claims in the speeches, such as the following:

Necessity of objective moral foundations in a state (Benedict XVI Citation2008, Citation2010, Citation2011).

Having the majority is not enough to fix laws related to the fundamental issues of the human being (Benedict XVI Citation2011).

Objective norms governing right action are accessible to reason prescinding from the content of revelation (Benedict XVI Citation2011).

The role of religion in the political sphere is to purify and shed light upon the application of reason to the discovery of objective moral principle (Benedict XVI Citation2010).

Defects in the positivist understanding of nature are evident in ecological problems (Benedict XVI Citation2011, Citation2008).

In all of these claims, biblical morality and natural law have a role. The idea of a ‘Creator spiritus’ (Benedict XVI Citation2011), the biblical creation account (2011), the idea of man’s creation in the image of God (2011), human dignity and equality before God (2011), the inviolable dignity of the human being (2008; 2011), the logos (2011), rationality of faith (2010), Catholic social doctrine themes such as the common good, the true meaning of freedom (2008) and religious freedom (2010) are examples of Catholic contents in Pope Benedict’s translation. They all project solidarity, universal brotherhood, and integral world vision. The humanizing role of religion in the development of civil society is a major trait of his speeches. For him religious freedom is necessary condition for the pursuit of truth. Pope Benedict XVI reaffirms the critical linkages of religious freedom and human dignity to the pursuit of justice, peace and truth and objective credibility which reason adduces to the profession of faith. For him religion and religious freedom are considered as building blocks of democracy.

6.6. Rhetoric of ‘open reason’

Pope Benedict XVI introduces a tool for orators, namely the rhetoric of 'open reason’. What does ‘open reason’ mean? It is the purification of positivist reason in the light of natural reason (Benedict XVI Citation2008, Citation2011). This reason is an alternative to the scientistic reduction of positivist reason. In contrast to positivist reason, 'open reason’ is open to all classical sources of knowledge of ethics and law, whereas positivist reason is a self-proclaimed exclusivity. Rhetoric of open reason is an attack against positivist understanding of reason and nature. For Benedict XVI, the positivist understanding of nature and reason is not wrong, but incomplete.

Pope Benedict demonstrates the weakness of scientistic reason through the green movement and ecological problems (Benedict XVI Citation2008, Citation2011). The point can be easily understood by the audience. It indicates that the earth is not just a raw material for us to shape at will, but it has inherent directives. He uses a special rhetorical imagination in the context. As in the case of nature there is an ecology of man. Man, too, has a nature that must be respected, and which he himself cannot manipulate at will (the role of natural law is evident).

He invites the audience to an integral openness to their own being and to reason. According to him, 'open reason’, as opposed to positivist reason, can reach the breadth and depth of the human being (Benedict XVI Citation2011), and is even open to divine transcendence. The fundamental aspiration of man is addressed here. Above all, we see in him a great trust in human reason and its ability to know the truth. He invites Catholic speakers into the wide world of rhetorical imagination of ‘open reason’ and its possibilities.

6.7. Flexibility of Pope Benedict XVI

Pope Benedict XVI always had the reputation of being a conservative speaker in public perception. But his speeches give evidence of flexibility. For example, he discerns the innumerable advantages of positivism in medical and scientific fields and appreciates it (Benedict XVI Citation2011), he acknowledges the majority criterion in democratic process for most of the matters to be regulated by law except in the cases of fundamental issues (2011), he welcomes dialogue between reason and faith, and interreligious dialogue at every level of society (2010), he accepts the non-competence of religion for providing political solutions (2010), he opens up about the pathologies of religion that pop up in a society that has no connection to reason (2010), he is aware that human reason is able to discover what is right (discernment of the right) even without the pre-knowledge of revelation (2010) etc. In summary, he gives a general impression that acting against reason is acting against God. It is interesting to note that he does not use words like euthanasia, abortion, genetic engineering etc. Instead, he talks about inviolability and human dignity and addresses the issues of scientism in his arguments (Benedict XVI Citation2008, Citation2010, Citation2011). Anthropological reading of his speeches will give many possibilities to explore especially the ecology of man (2011). He is very proficient at finding common values, between the state or organization he is speaking to, and the Catholic Church (2008; 2010; 2011). Believing in the capacity of human reason, he welcomes dialogue with all levels of society and he adopts a model of giving reason.

7. Relevance of critical distance and translation model in public speeches

How should a Catholic speaker understand this translation of religious content? It is a kind of jumping over the boundaries of religion or transcending the semantic domain of religious community to the secular language. The term secular needs to be restricted here. It is an attempt to connect to secular reasoning, not to the negation of religious faith. Pope Benedict makes the Faith reasonable to the public. The objective of translation is to inspire people with Catholic religious wisdom while respecting pluralistic belief. But the original spark, which is Catholic, remains in the translated content. It is important for Catholic speakers to earn their place in the public sphere by the integrity of the position they seek to defend and the rational basis on which their arguments are founded. In this model Pope Benedict uses scientific, philosophical, historical, cultural, anthropological and logical terminologies to connect with the audience, which gives a clear idea about his interdisciplinary approach (Jose Citation2023, 500).

What should be the rhetorical imagination of a Catholic speaker in a public address?

Pope Benedict’s model of critical distance is one of the possible answers to the question. He creates critical distance in his speech by translating religious contents into secular language. Natural law and natural reason help him in the process. General findings of the analysis give the idea that enthymeme, logical and conceptually true statements, examples from historical events and its reflection, commonly known institutional rules help him to translate religious contents into secular audience. Here the speaker creates a reasonable space between himself and the audience. Moreover, he gives reasonable response in advance for the possible questions from the audience, using an interdisciplinary approach. All these make for that creative space between persons in public in which relationships can occur, permitting creativity and difference to be the driving force within the public domain.

In his arguments Pope Benedict XVI is very sure about the role of religion in the political sphere and in the national conversation. Public recognition on the part of the nation of the contributions of religion is an important part of religious freedom; other it affects the unity of the person and human dignity. (Benedict XVI Citation2008). Unity of the person is thoroughly related to self-flourishing and thus to human dignity. It is to be protected by the state for two reasons. The first reason is that man is in the image of God, and thus he has dignity. In other words, he is not just an object or aggregate of matter that accidently evolved in the universe, but has an intrinsic value.

The second reason is that man is a relational being oriented both towards society and to the transcendental dimension. These relational aspects must be encouraged not only in worship and liturgy but also in accepting the public dimension of religion. Otherwise, the unity of the person will be fragmented. Such fragmentation hurts man’s dignity – his most basic right. And it will affect the common good. Religious freedom and human dignity are interdependent.

Thus, for Pope Benedict, religious freedom is not just the right to worship and to propagate the faith, but also incorporates human dignity and is thus a fundamental right. In the speeches one can find many tangible examples of the role of religion in the state (Benedict XVI Citation2010). At the same time, Benedict XVI is aware of the non-competence of the Church to furnish political solutions or public policies for the nation (2010).

8. Limitation of the study

There are also limitations to the study, particularly the sample size of the speeches. The lack of feedback analysis is another drawback. Normally, controversies, counterarguments, and proposals from different parts of society are projected in the media in response to the discourse. Obtaining this feedback for analysis is very important for determining the effectiveness of the speeches, which I could not present in the study. Analysing the feedback will help to increase the reliability of the result, which could be important for the future direction of studies on the topic. Since Pope Benedict XVI produced a large collection of public speeches, it is valuable to capture his arguments and their components using Freeman’s model. Certainly, it will provide us with interesting examples, metaphors, and other linguistic devices. I think it will give new direction and new language to Catholic speakers, and thus to Catholic public speaking in general.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jottin Jose

Jottin Jose is a Catholic priest from the Archdiocese of Ernakulam-Angamaly (India). He has a PhD in Church Communications from the Pontifical University of Holy Cross, Rome, and is Editor of the Pastoral magazine Vachanadhara.

Notes

1 More details can be found in Blanco Sarto (Citation2011).

2 Michael J. Hostetler is a pastor and professor of the Department of Rhetoric, Communication, and theatre at St. John’s University in New York.

3 David Tracy is a priest and professor of theology known for his work in hermeneutics and theological method in a pluralistic context.

4 Michael J. Perry is author of thirteen books and eighty-five articles. His area of expertise is in Constitutional Law, especially Constitutional Rights, Human Rights Theory, and Law and Religion.

5 Ronald C. Arnett is professor Emeritus of Duquesne University and expert in communicative studies. He is currently serving his third editorship for the Journal of Communication and Religion.

6 James B. Freeman is Professor emeritus of Philosophy at the Department of Philosophy, Hunter College of City University of New York. He is expert in Argumentation Theory and Logic.

7 Stephen Toulmin (1922–2009) is famous for his studies of prescriptive language and moral reasoning. For him moral language cannot be reduced to subjective or objective but is unique expression of duty and right.

8 More details about the subject can be found in the article ‘Concerning the Notion of Person in Theology’ (Ratzinger Citation1990).

References

- Arnett, Ronald C. 2013. Communication Ethics in Dark Times: Hannah Arendt’s Rhetoric of Warning and Hope. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

- Benedict XVI. 2008. "Meeting with the Members of the General Assembly of the United Nations Organization." Vatican.va. https://www.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/en/speeches/2008/april/documents/hf_ben-xvi_spe_20080418_un-visit.html.

- Benedict XVI. 2009. “Encyclical Letter Caritas in Veritate." Vatican.va. https://www.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/en/encyclicals/documents/hf_ben-xvi_enc_20090629_caritas-in-veritate.html.

- Benedict XVI. 2010. "Address of Pope Benedict XVI in Westminster Hall.” Vatican.va. https://www.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/en/speeches/2010/september/documents/hf_ben-xvi_spe_20100917_societa-civile.html.

- Benedict XVI. 2011. “Address of His Holiness Benedict XVI in the Reichstag Building, Berlin.” Vatican.va. https://www.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/en/speeches/2011/september/documents/hf_ben-xvi_spe_20110922_reichstag-berlin.html.

- Blanco Sarto, Pablo. 2011. La Teologia de Joseph Ratzinger: Una Introduccion. Madrid: Pelicano

- Edwards, Jason A., and David, Weiss, eds. 2011, ‘The Rhetoric of American Exceptionalism: Critical Essays’ Jefferson N.C. McFarland and Co.

- Freeman, James B. 2005a. “Systematizing Toulmin’s Warrant: An Epistemic Approach." Ontario Society for the Study of Argumentation. OSSA Conference Papers. University of Windsor, Ontario. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/ossaarchive/OSSA6/papers/16/.

- Freeman, James B. 2005b. Acceptable Premises: An Epistemic Approach to an Informal Logic Problem. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Gutmann, Amy, and Thompson Denny. 2004. Why Deliberative Democracy? Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Hostetler, Michael J. 2013. “Talking about Religion in the Public: Finding Critical Distance.” Journal of Communication & Religion 36 (3): 77–89.

- International Theological Commission. 2009. Alla Ricerca Di Un’ Etica Universale: Nuovo Sgaurdo Sulla Legge Naturale. Documenti 2005-2021. Bologna: Edizione Studio Dominicano.

- Jose, Jottin. 2023. “Rhetoric of Natural Law and Translation of Religious Contents in the secular language: A qualitative Study Based on the Public Discourse of Pope Benedict XVI.” PhD diss., Pontifical University of Santa Croce. Independently published on Amazon.

- Morgan, Auston. 2017. "Religious Freedom: Human Rights." 33 Bedford Row. https://www.33bedfordrow.co.uk/insights/articles/religious-freedom-human-rights

- Puppinck, Gregor. 2013. “UK Employees Cases: A Step Back for Freedom of Conscience and Religion in Europe.” www.eclj.org. https://eclj.org/religious-freedom/echr/uk-christian-employees-cases-a-step-back-for-freedom-of-conscience-and-religion-in-europe.

- Ratzinger, Joseph. 1968. Introduction to Christianity. Translated by J. R. Foster. San Francisco: Ignatius Press,2004

- Ratzinger, Joseph. 1988. Church, Ecumenism, Politics. Translated by Nowell Robert. New York: Crossroad.

- Ratzinger, Jospeh. 1990. “Concerning the Notion of Person in Theology.” Communio 17 (Fall 1990): 439–454.

- Ratzinger, Joseph, and Jürgen Habermas. 2006. The Dialectics of Secularization on Reason and Religion. San Francisco: Ignatius Press.

- Toulmin, Stephan E. 2003. Uses of Argument. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Tracy, David. 1987. Plurality and Ambiguity: Hermeneutics, Religion, Hope. San Francesco: Harper & Row.

- Vallely, Paul. 2010. “Not Just a White Christmas.” Independent, December 24. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/not-just-a-white-christmas-in-luton-2168414.html.