ABSTRACT

The introduction of exotic fishes in streams and water reservoirs has modified autochthonous freshwater fish communities in Puerto Rico. There are approximately 46 fish species in inland waters, and most of them were introduced during the last century. We here summarize relevant information on 46 freshwater fish species reported for the island. Approximately 80% of the species are non-native. An evaluation of the local trade revealed another 128 freshwater fish species are sold locally as pets. This raises serious concerns, as we detected a potential pool of non-native species that are either considered invasive elsewhere, or that, based on their ecology, could become invasive on the island in the near future. We also found that cichlids as a group pose the highest risk to freshwater ecosystems, with 13 species established in the wild, and another 38 potential invaders in the local pet trade. This study may be used as a baseline for the conservation and management purposes of both native and non-native fish species, including the development of strategies for preventing the release of live fish pets into the wild. More specific management for non-native fish, especially those identified here that pose significant threats to Puerto Rico’s native fish and their ecosystems, are warranted.

Introduction

The Neotropical realm has the highest diversity of freshwater fish, with more than 5,160 recorded species worldwide [Citation1]. Native freshwater fish communities on tropical islands usually have low species diversity and are composed entirely of species with catadromous or amphidromous life histories [Citation2,Citation3]. Puerto Rico has nine native freshwater fish species, all of which require contact with marine environments during some phase of their life cycle [Citation4]. These native species include representatives within the families Anguillidae, Eleotridae, Gobiidae, and Mugilidae [Citation5,Citation6]. Today, however, there are about 77 reported freshwater fish species that inhabit the inland waters of Puerto Rico [Citation3].

Unsustainable human development has considerably impacted freshwater ecosystems globally, and native freshwater fish face a variety of threats [Citation7]. Catchment-scale modifications (i.e. altered movement pathways of sediments in water systems due to land-use changes or increased imperviousness) and stream channelization projects in urban areas, often employed as a strategy to control flooding, have a strong impact on the distribution and composition of fish species and their communities [Citation8]. Hence, the migratory patterns and life cycles associated with the development of a species are modified or broken, and thus the native species assemblages become overtaxed, while the establishment of exotic species remains rampant [Citation5,Citation9].

Highly urbanized areas degrade freshwater ecosystems due to the interplay between the loss of appropriate habitat for native fish species and the proliferation of introduced non-native species (which are often more tolerant to disturbed ecosystems), resulting in a decrease of native freshwater fish diversity [Citation10], and in the loss of the ecological services they provide [Citation11]. In Puerto Rico, over the last century, anthropogenic disturbances such as the modification of watersheds through the alteration of river courses, construction of dams, channelization of reaches, deforestation, road crossings, water pollution, and changes in the species composition – which includes the introduction of non-native fish – have greatly modified the inland freshwater ecosystems [Citation12]. For example, dam construction and some channel modifications serve as barriers to Puerto Rico’s native fish species, affecting their migratory patterns and species assemblages of native fish. Most the major rivers of Puerto Rico have some degree of damming (i.e. water retention structures), which has negatively impacted freshwater fish communities through habitat fragmentation [Citation13].

With the establishment of Biological Invasion as a discipline, we now know, without a doubt, that the detrimental effects of biological invasions have intensified greatly during the last decades [Citation14]. The ever-present threat of new introductions on non-native fish to indigenous ecosystems represents a serious threat to freshwater systems, especially on island ecosystems. The introduction of non-native fish in the inland freshwater systems of Puerto Rico has severely impacted native fish communities, with local depletion or local extinction of native species [Citation3,Citation8,Citation15]. Currently, freshwater habitats are mostly composed of fish species introduced from America, Africa and Asia [Citation15]. Although the introduction of non-native fish into the water reservoirs of Puerto Rico began in the early 1900s, most of the non-native species present in the wild today are the result of both accidental and intentional releases during the last decades. Non-native fishes were brought for aquaculture and the sport fishing industries, and some escaped from fish hatcheries and fishponds that were mainly established in the 1930s [Citation16]. Hence, species such as goldfish (Carassius auratus), swordtails (Xiphophorus hellerii), sailfin catfish (Pterygoplichthys sp.), algae-eater (Gyrinocheilus aymonieri), and several cichlid species have been released to the wild by their owners and have become common throughout the island [Citation17]. What ecological impacts these non-native fish may have on native species is a shared concern amongst scientists that study freshwater ecosystems in Puerto Rico. For example, predation by introduced non-native freshwater fish upon native snail and bird species has been reported in Puerto Rico [Citation18].

Early studies of freshwater fish communities in Puerto Rico focused on biological aspects of native species [Citation19,Citation20,], and they gradually shifted to include species distributions, the biology and management of non-native species, and the impacts of these on native freshwater fish communities [Citation15]. More recently, studies have focused on the effects of ecological factors influencing freshwater fish populations and communities (e.g. parasitization), genetics, and urban fish assemblages [Citation8,Citation17,Citation21,Citation22]. However, and although Puerto Rican freshwater ecosystems are relatively well studied when compared to other islands, biologists keep recording new species established in the wild. For example, just in 2018, Rodríguez-Barreras and Zapata-Arroyo [Citation23] recorded the occurrence of an established population of the highly invasive African catfish Clarias gariepinus in Puerto Rico, a species considered harmful to native species elsewhere, which raised grave concerns amongst state and federal agencies tasked with the management of the native and sport fish resources of the island.

The availability of scientific information on the identity of both native and non-native fish species that currently inhabit the island, and on locally traded non-native freshwater fish is critical to effectively manage the freshwater fish resources. However, there is currently no updated list of freshwater species to accomplish this. To fill this gap, here we present a comprehensive list of native and non-native freshwater fish species established in Puerto Rico, and the species that have not yet been reported in the wild, but that are traded locally. For the freshwater fish fauna that are present in the wild, we synthesize the most relevant information, which includes aspects of their biology, ecology, and their geographic distribution. Additionally, we provide information about freshwater fish species that are sold through the aquarium pet trade in Puerto Rico and their potential invasiveness.

Methods

Site description

The Puerto Rican Archipelago is located in the Caribbean Sea, and composed of three main populated-islands (Puerto Rico, Vieques, and Culebra), and numerous other islands, islets and cays, which, together with the US and UK Virgin Islands (except for St. Croix) form the biogeographic area known as the Puerto Rican Bank. This study focuses on the main island of the Puerto Rican Archipelago, Puerto Rico, which is the smallest of the Greater Antilles, with an area of approximately 8,870 km2. Puerto Rico currently has a human population of approximately 3.2 million inhabitants with a human-population density of ca. 351 inhabitants per km2, after experiencing a dramatic decrease in population (of ca. −0.5 million, or a 15.3% decrease) in just 8 years [Citation24]. Geologically, Puerto Rico is of volcanic origin, but possesses karst regions [Citation17], and has diverse climatic zones [Citation25]. The climatic zones of the freshwater systems of the island vary from perennial streams in areas of high precipitation, to intermittent streams in areas of low precipitation [Citation26]. The Central Cordillera is the main mountainous chain that runs east-west through the center of Puerto Rico. It reaches 1,340 m at its highest point and is the origin of most of the rivers and streams on the island. The rivers and streams draining towards the north include many underground systems flowing through the Karst Region and include the longest river systems on the island, whereas there are fewer and shorter length rivers and streams draining towards the south [Citation27,Citation28]. When compared to the other Greater Antilles, the rivers and streams of Puerto Rico are generally small and flashy, and composed of mainly rocky substrates of volcanic origin (e.g. pebbles, gravel, boulders) and sand.

Compilation of fish species present in puerto rico

To generate a comprehensive and updated list of freshwater fish species present in Puerto Rico that may be used to inform conservation and management strategies, we focused on identifying: i) species present in the wild, and ii) locally traded species, especially those present only in captivity (i.e. that may be potentially released into the wild).

Fish species present in the wild

To compile a list of fish species present in the wild, we reviewed the literature (which included published and unpublished scientific articles and technical reports of government agencies), performed a survey of specimens collected and deposited in zoological collections, and carried out sampling in-situ.

To identify the species of fish present in the wild, we considered species with life histories recognized as catadromous, amphidromous and stream resident. We excluded fish species with life histories dominated primarily by phases inhabiting marine, estuarine and brackish water habitats. To compile a list of fish species present in the wild, we reviewed the literature – which included published and unpublished scientific articles and technical reports of government agencies, performed a survey of specimens collected and deposited in zoological collections, and carried out sampling in-situ. Local distribution for all species was not uniform due to differences in information sources.

To perform the literature review, we used the institutional database of the library in the University of Puerto Rico, and search engines using the keywords: “freshwater”, “fish”, “exotic species”, and “Puerto Rico”. To complement the information extracted from the literature, we surveyed the specimens deposited in the Zoological Museum of the University of Puerto Rico – Río Piedras Campus. For each collection, we recorded the following information: sample identification number (ID), species identity, number of individuals, and collection date.

We conducted fish surveys in four locations in the metropolitan area of San Juan, which includes Guaynabo River (18°21ʹ59,78”N, 66°06ʹ41,32”W; [June/2018]), a tributary of the Guaynabo River in the Camarones suburb (18°12ʹ20,52”N, 66°03ʹ48,99”W; [June/2018]), a tributary of the Bayamón River (18°22ʹ11,03”N, 66°8ʹ49,69”W; July/2018]), and Mameyes River, located in Rio Grande (18°19ʹ26,57”N, 65°44ʹ55,89”W; [July/2018]). Sites were selected because these are areas of high suspected invasion potential due to proximity to aquaria owners and have not been frequently sampled. Fish species were identified visually by snorkeling or by capturing them using a hand net. All captured individuals were released immediately after identification.

Locally traded fish species

To identify locally traded fish species, primarily through the aquarium (ornamental) and pet trade markets, and to identify those species that have invasive potential, we followed Falcón and Tremblay [Citation29]. Briefly, during April of 2019, we conducted surveys in situ, focusing on pet- and aquarium shops in the Metropolitan Area of San Juan. Moreover, we surveyed online community groups covering topics related to biodiversity, pet trade, aquarium fish, and collected available posted data (e.g. location, species, photographs). Surveyed Facebook (http://www.facebook.com) groups included The fish outlet, Nativos Ciclids fish shop, Adictos a los peces, Báez Aquarium and more, Aquarium Xtra, and Pet Ways (see Supplemental Information). We also surveyed the pet section of local online classified (user-generated ads) webpage Clasificados Online.

Scientific name nomenclature

After taxonomic identification (at the lowest possible level), we followed the nomenclature established by the Integrated Taxonomic Information System to assign the corresponding scientific name for each identified taxon, and updated the scientific name of fish reported in the literature or preserved in zoological collections, as needed [Citation30]. We provide common names for fish currently present in the wild in Puerto Rico in both English and Spanish in .

Table 1. Freshwater fish species found in reservoirs and rivers of the Island of Puerto Rico. We include species name, common name (English and/or Spanish), occurrence (native/introduced), and migratory status (resident, present (1 or few localities), amphidromous, catadromous). Pet trade indicates if the species is known to be currently sold as pet (Y) or unknown (U) in Puerto Rico. Resident

Results

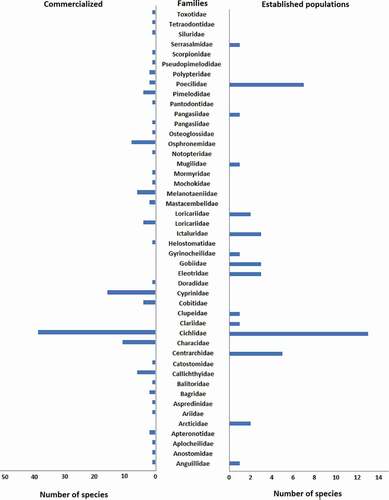

We report 46 freshwater fish for Puerto Rico freshwater systems, belonging to 7 orders, 14 families, and 32 genera (, ). The Order Perciformes was the best represented with 26 species, whereas the Orders such as Anguilliformes and Characiformes were represented only by one species (). The family Cichlidae was the best represented with 13 species followed by Poeciliidae with 7 species, both families include only non-native species (). Most fish species found in Puerto Rico’s streams and water reservoirs are non-native; only 9 species of this list are native, which represents 19.6% of the total number of freshwater fish species reported for Puerto Rico. We also found another 128 freshwater fish species commercialized in stores and local websites. The most represented families were Cichlidae with 39 species, Cyprinidae with 16 species and Characidae with 11 species (). See Appendix 1 for more details.

Figure 1. Freshwater fish species found in reservoirs and rivers of the Island of Puerto Rico. Species lengths are to scale between species in these images. Anguilla rostrata (1), Myleus rubripinnis (2), Dorosoma petenense (3), Carassius auratus (4), Pethia conchonius (5), Gyrinocheilus aymonieri (6), Gambusia affinis (7), Poecilia latipinna (8), Poecilia reticulata (9), Poecilia vivipara (10), Poecilia sphenops (11), Xiphophorus hellerii (12), Xiphophorus maculates (13), Agonostomus monticola (14), Micropterus chattahoochae (15), Micropterus salmoides (16), Lepomis auritus (17), Lepomis macrochirus (18), Lepomis microlophus (19), Archocentrus nigrofasciatus (20), Amphilophus citrinellus (21), Amphilophus labiatus (22), Astronotus ocellatus (23), Cichla ocellaris (24), Herichthys cyanoguttatum (25), Oreochromis aureus (26), Oreochromis mossambicus (27), Oreochromis niloticus (28), Parachromis managuensis (29), Thorichthys meeki (30), Tilapia rendalli (31), Vieja melanura (32), Dormitator maculatus (33), Eleotris perniger (34), Gobiomorus dormitor (35), Awaous banana (36), Sicydium plumieri (37), Sicydium punctatum (38), Pangasius hypophthalmus (39), Clarias gariepinus (40), Ameiurus catus (41), Ameiurus nebulosus (42), Ictalurus punctatus (43), Pterygoplichthys multiradiatus (44), and Pterygoplichthys pardalis (45). There were no available pictures for Sicydium buscki.

Figure 2. Number of freshwater fish by families with natural populations established in Puerto Rico (left), and commercialized in pet stores and local websites, with no natural populations (right)

The following list includes all freshwater fish species with established populations on the island:

Order AnguilliformesFamily Anguillidae Rafinesque, 1810Anguilla rostrata (Lesueur, 1817)

Distribution

Northwest to western Central Atlantic: Greenland south along the Atlantic coast of Canada and the USA to Panama and throughout much of the south Caribbean to Trinidad.

Puerto Rico localities: Found in nearly all rivers of Puerto Rico in the lowlands. Occasionally found in farms and reservoirs. Canóvanas River (18°23ʹ48,18”N, 65°54ʹ44,89”W), Herrera River (18°33ʹ01,20”N, 65°51ʹ50,27”W), Tabonuco Ravine (18°21ʹ15,53”N, 65°28ʹ09,18”W), Mameyes River (18°19ʹ26,57”N, 65°44ʹ55,89”W), Sabana River (18°15ʹ44,05”N, 65°47ʹ39,13”W), Pitahaya River (18°21ʹ53,73”N, 65°43ʹ06,53”W), Juan Martín River (18°21ʹ07,85”N, 65°41ʹ00,90”W), Juan Diego Ravine (18°18ʹ27,67”N, 65°46ʹ08,63”W), Rincón Ravine (18°17ʹ18,25”N, 65°41ʹ37,67”W), Guayanés River (18°04ʹ12,51”N, 65°50ʹ32,70”W), Caño Santiago (18°03ʹ29,08”N, 65°49ʹ32,71”W), Maunabo River (18°00ʹ12,59”N, 65°54ʹ13,65”W), Tallaboa River (18°02ʹ17,33”N, 66°43ʹ17,40”W), Guayanilla River (18°18ʹ12,33”N, 66°47ʹ55,91”W), Yauco River (17°59ʹ23,53”N, 66°50ʹ24,92”W), Loco River (18°00ʹ53,10”N, 66°52ʹ33,10”W), Los Llanos Ravine (18°01ʹ44,65”N, 67°06ʹ49,65”W), Yagüez River (18°12ʹ26,80”N, 67°07ʹ07,81”W), Blanco River (18°13ʹ46,94”N, 65°47ʹ09,12”W), Prieto River (18°15ʹ19,81”N, 65°46ʹ52,57”W), Toro Negro River (18°13ʹ49.25”N, 66°30ʹ44,99”W), Cialitos River (18°17ʹ09,70”N, 66°30ʹ53,76”W), Río Piedras River (18°24ʹ00,98”N, 66°03ʹ42,58”W), Great River of Arecibo (18°24ʹ06,07”N, 66°41ʹ27,10”W), Ingenio River (18°04ʹ33,66”N, 65°50ʹ34,40”W), Caño Tiburones (18°28ʹ34,59”N, 66°37ʹ51,53”W), and Cartagena (18°00ʹ51,06”N, 67°06ʹ16,17”W) and Tortuguero (18°27ʹ50,37”N, 66°26ʹ36,91”W) lagoons.

References [Citation3,Citation16,Citation31,Citation34].

Remarks: I-00003, three organisms collected on 28 March 1969; I-00004, one org. collected on 03 June 1969; I-00005, four orgs. collected on 03 June 1969; I-00006, one org. collected on 08 March 1976; I-00007, one org. collected on 14 June 2000; and I-00008, two orgs. collected on 22 May 1999.

Order Characiformes

Family Serrasalmidae Bleeker, 1859

Myleus rubripinnis (Müller and Troschel, 1844)

Distribution

Naturally occurs in South America: Amazon and Orinoco River basins; and Guiana Shield rivers.

Puerto Rico localities: Cerrillos reservoir (18°05ʹ49,92”N, 66°34ʹ43,83”W).

References [Citation35,Citation36].

Order ClupeiformesFamily Clupeidae Cuvier, 1816Dorosoma petenense (Günther, 1867)

Distribution

North and Central America: Gulf of Mexico drainage, Mississippi system, from the Ohio River of Kentucky and southern Indiana southwest to Oklahoma, and south to Texas and Florida, also rivers around the Gulf to northern Guatemala; also found in Belize Rivers. Introduced in Hawaiian waters, and in Chesapeake Bay tributaries.

Puerto Rico localities: in May 1963, 40 adults from Georgia were introduced to Guajataca reservoir (18°23ʹ26,86”N, 66°55ʹ25,94”W). Currently found in Great River of Arecibo (18°24ʹ06,07”N, 66°41ʹ27,10”W), and in most of the island reservoirs.

References [Citation15,Citation16,Citation36].

Remarks: I-00012, four organisms collected on 14 June 2000; and I-00017, three orgs. collected on 15 June 2000.

Order Cypriniformes

Family Arcticidae Newton, 1891

Carassius auratus (Linnaeus, 1758)

Distribution

Worldwide distributed, but originally from Asia: central Asia and China and Japan.

Puerto Rico localities: Guajataca (18°23ʹ26,86”N, 66°55ʹ25,94”W), and Guayabal (18°05ʹ44,53”N, 66°30ʹ14,13”W) reservoirs, but also in small ponds around the island.

References [Citation16,Citation36,Citation37].

Pethia conchonius (Hamilton, 1822)

Distribution

Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Pakistan, India, Nepal, and Myanmar.

Puerto Rico localities: Cagüitas River (18°13ʹ52,39”N, 66°03ʹ05,79”W), Cañas River (18°17ʹ22,84”N, 66°03ʹ58,96”W), Canovanillas River (18°19ʹ17,07”N, 65°54ʹ13,36”W), Majada River (18°02ʹ30,63”N, 66°12ʹ36,38”W), Yunes River (18°19ʹ21,34”N, 66°35ʹ15,67”W), Barranquita River (18°10ʹ24,90”N, 66°17ʹ53,82”W), La Zapatera Ravine (18°07ʹ23,70”N, 66°05ʹ07,65”W), Patillas Canal (17°58ʹ40,63”N, 66°08ʹ56,52”W), Loiza (18°18ʹ54,98”N, 66°01ʹ14,52”W) and Dos Bocas (18°19ʹ57,68”N, 66°40ʹ05,12”W) reservoirs.

References [Citation3,Citation36,Citation38].

Family Gyrinocheilidae Gill, 1905

Gyrinocheilus aymonieri (Tirant, 1883)

Distribution

Asia (Mekong, Chao Phraya and Meklong basins, and the northern Malay Peninsula).

Puerto Rico localities: Cañas River (18°17ʹ22,84”N, 66°03ʹ58,96”W).

References [Citation3,Citation36,Citation39].

Family Poeciliidae Bonaparte, 1831

Gambusia affinis (Baird and Girard, 1853)

Distribution

North and Central America: Mississippi River basin from central Indiana and Illinois in the USA south to The Gulf of Mexico and Gulf Slope drainages west to Mexico.

Puerto Rico localities: Considered the most abundant fish in the freshwater reservoirs of the island. Found in the following reservoirs: Carite (18°04ʹ44,13”N, 66°06ʹ00,05”W), Caonillas (18°16ʹ28,90”N, 66°39ʹ10,30”W), Dos Bocas (18°19ʹ57,68”N, 66°40ʹ05,12”W), Guayabal (18°05ʹ44,53”N, 66°30ʹ14,13”W), Loiza (18°18ʹ54,98”N, 66°01ʹ14,52”W), Patillas (18°01ʹ27,38”N, 66°01ʹ23,76”W), and Toa Vaca (18°06ʹ09,99”N, 66°28ʹ57,91”W) reservoirs. Also, near the coast, all the way upstream to the headwaters at Mount Guilarte.

References [Citation16,Citation34,Citation36].

Poecilia latipinna (Lesueur, 1821)

Distribution

North America: From Cape Fear drainage in North Carolina in the USA to Veracruz in Mexico.

Puerto Rico localities: Great River of Loiza (18°23ʹ48,19”N, 65°54ʹ44,89”W), and Canóvanas River (18°23ʹ48,18”N, 65°54ʹ44,89”W).

References [Citation3,Citation34].

Remarks: I-00029, + 200 organisms collected on 21 March 1998; and I-00030, 50 orgs. collected on 03/21/1998.

Poecilia reticulata Peters, 1859

Distribution

South America: Venezuela, Barbados, Trinidad, northern Brazil and the Guyanas. Widely introduced and established elsewhere, mainly for mosquito control, but had rare to non-existing effects on mosquitoes, and negative to perhaps neutral effects on native fish. Africa: Feral populations reported from the coastal reaches of Natal river from Durban southwards, as well as in the Kuruman Eye and Lake Otjikoto in Namibia.

Puerto Rico localities: Guaynabo River (18°21ʹ59,78”N, 66°06ʹ41,32”W), tributary to Bayamón river (18°22ʹ11,61”N, 66°08ʹ33,44”W), Cagüitas River (18°13ʹ52,39”N, 66°03ʹ05,79”W), Cañas River (18°17ʹ22,84”N, 66°03ʹ58,96”W), Canovanillas River (18°19ʹ17,07”N, 65°54ʹ13,36”W), Canóvanas River (18°23ʹ48,18”N, 65°54ʹ44,89”W), Herrera River (18°33ʹ01,20”N, 65°51ʹ50,27”W), Humacao River (18°09ʹ03,55”N, 65°51ʹ55,77”W), Guayanés River (18°04ʹ12,51”N, 65°50ʹ32,70”W), Majada River (18°02ʹ30,63”N, 66°12ʹ36,38”W), Descalabrado River (18°03ʹ57,07”N, 66°25ʹ48,19”W), Macaná River (18°00ʹ51,57”N, 66°45ʹ55,35”W), Yauco River (17°59ʹ23,53”N, 66°50ʹ24,92”W), Los Llanos Ravine (18°01ʹ44,65”N, 67°06ʹ49,65”W), Blanco River (18°13ʹ46,94”N, 65°47ʹ09,12”W), Prieto River (18°15ʹ19,81”N, 65°46ʹ52,57”W), Juncal River (18°17ʹ10,99”N, 66°53ʹ39,73”W), Guatemala River (18°20ʹ35,75”N, 66°59ʹ59,16”W), Salada Ravine (18°21ʹ04,74”N, 67°01ʹ32,95”W), tributaries to Culebrinas River, Camuy River (18°27ʹ00,37”N, 66°49ʹ36,47”W), Naranjito River (18°16ʹ55,50”N, 66°35ʹ00,61”W), Limón River (18°19ʹ33,34”N, 66°36ʹ56,01”W), La Ventana River (18°10ʹ29,79”N, 66°21ʹ05,86”W), Yunes River (18°19ʹ21,34”N, 66°35ʹ15,67”W), Tanamá River (18°24ʹ39,05”N, 66°42ʹ54,54”W), Jobos Ravine (18°19ʹ18,03”N, 66°40ʹ46,04”W), Great River of Manatí (18°24ʹ31,31”N, 66°29ʹ46,04”W), Cañabón River (18°13ʹ24,69”N, 66°20ʹ17,26”W), Bauta River (18°17ʹ52,09”N, 66°27ʹ35,69”W), Sana Muerto River (18°17ʹ12,32”N, 66°25ʹ19,97”W), Cialitos River (18°17ʹ09,70”N, 66°30ʹ53,76”W), Maravilla River (18°21ʹ05,76”N, 66°17ʹ50,17”W), Morovis River (18°20ʹ57,45”N, 66°23ʹ10,50”W), Unibón River (18°20ʹ36,43”N, 66°22ʹ50,04”W), Barranquita River (18°10ʹ24,90”N, 66°17ʹ53,82”W), La Zapatera Ravine (18°07ʹ23,70”N, 66°05ʹ07,65”W), and Río Piedras River (18°24ʹ00,98”N, 66°03ʹ42,58”W).

References [Citation3,Citation36,Citation40].

Remarks: I-00031, 25 organisms collected on unknown date; I-00032, 1 org. collected on 20 May 2002; I-00033, 2 orgs. collected on 01 March 1998; I-00034, 3 orgs. collected on 01 March 1999; I-00035, 1 org. collected on unknown date; I-00036, 4 orgs. collected on 25 March 1997, I-00042, 15 orgs. collected on 20 March 1969; and I-00043, 1 org. collected on 14 March 1969.

Poecilia vivipara Bloch and Schneider, 1801

Distribution

South America, between Suriname and Brazil (not the Atlantic area South of the Laguna dos Patos basin in Brazil). Also introduced in the Caribbean.

Puerto Rico localities: Reported at Ponce, Fajardo, Arroyo, Guánica, and Comerio municipalities, Cartagena reservoir (18°00ʹ51,06”N, 67°06ʹ16,17”W), Aibonito River (18°09ʹ39,98”N, 66°18ʹ18,41”W), Ingenio River (18°04ʹ33,66”N, 65°50ʹ34,40”W), Guayanés River (18°04ʹ12.51”N, 65°50ʹ32.70”W), and the mouth of the Loiza River (18°25ʹ57,43”N, 65°53ʹ02,61”W),

References [Citation31,Citation32,Citation33,Citation41,Citation42,Citation43].

Remarks: I-00037, two organisms collected on 15 March 1998; I-00038, five orgs. collected on 22 March 1969; and I-00040, five orgs. collected on unknown date.

Poecilia sphenops Valenciennes in Cuvier and Valenciennes, 1846

Distribution

Central and South America: Mexico to Colombia.

Puerto Rico localities: Guaynabo River (18°21ʹ59,78”N, 66°06ʹ41,32”W), Cagüitas River (18°13ʹ52,39”N, 66°03ʹ05,79”W), Cañas River (18°17ʹ22,84”N, 66°03ʹ58,96”W), Canovanillas River (18°19ʹ17,07”N, 65°54ʹ13,36”W), Canóvanas River (18°23ʹ48,18”N, 65°54ʹ44,89”W), Majada River (18°02ʹ30,63”N, 66°12ʹ36,38”W), Descalabrado River (18°03ʹ57,07”N, 66°25ʹ48,19”W), Yauco River (17°59ʹ23,53”N, 66°50ʹ24,92”W), Guatemala River (18°20ʹ35,75”N, 66°59ʹ59,16”W), tributaries to Culebrinas River, Camuy River (18°27ʹ00,37”N, 66°49ʹ36,47”W), Naranjito River (18°16ʹ55,50”N, 66°35ʹ00,61”W), Limón River (18°19ʹ33,34”N, 66°36ʹ56,01”W), La Ventana River (18°10ʹ29,79”N, 66°21ʹ05,86”W), Yunes River (18°19ʹ21,34”N, 66°35ʹ15,67”W), Great River of Manatí (18°24ʹ31,31”N, 66°29ʹ46,04”W), Cañabón River (18°13ʹ24,69”N, 66°20ʹ17,26”W), Sana Muerto River (18°17ʹ12,32”N, 66°25ʹ19,97”W), Toro Negro River (18°13ʹ49.25”N, 66°30ʹ44,99”W), Cialitos River (18°17ʹ09,70”N, 66°30ʹ53,76”W), Maravilla River (18°21ʹ05,76”N, 66°17ʹ50,17”W), Unibón River (18°20ʹ36,43”N, 66°22ʹ50,04”W), Barranquita River (18°10ʹ24,90”N, 66°17ʹ53,82”W), and La Zapatera Ravine (18°07ʹ23,70”N, 66°05ʹ07,65”W).

References [Citation3,Citation44].

Xiphophorus hellerii Heckel, 1848

Distribution

North and Central America: Rio Nantla, Veracruz in Mexico to northwestern Honduras. Africa: Feral populations reported from Natal and eastern Transvaal as well as in Lake Otjikoto, Namibia.

Puerto Rico localities: tributary to Bayamón River (18°22ʹ11,61”N, 66°08ʹ33,44”W), Guaynabo River tributary (18°12ʹ20,52”N, 66°03ʹ48,99”W), Loiza Reservoir (18°18ʹ54,98”N, 66°01ʹ14,52”W), Cañas River (18°17ʹ22,84”N, 66°03ʹ58,96”W), Humacao River (18°09ʹ03,55”N, 65°51ʹ55,77”W), Yauco River (17°59ʹ23,53”N, 66°50ʹ24,92”W), Los Llanos Ravine (18°01ʹ44,65”N, 67°06ʹ49,65”W), Blanco River (18°13ʹ46,94”N, 65°47ʹ09,12”W), Prieto River (18°15ʹ19,81”N, 65°46ʹ52,57”W), Juncal River (18°17ʹ10,99”N, 66°53ʹ39,73”W), Guatemala River (18°20ʹ35,75”N, 66°59ʹ59,16”W), Camuy River (18°27ʹ00,37”N, 66°49ʹ36,47”W), Naranjito River (18°16ʹ55,50”N, 66°35ʹ00,61”W), Limón River (18°19ʹ33,34”N, 66°36ʹ56,01”W), La Ventana River (18°10ʹ29,79”N, 66°21ʹ05,86”W), Yunes River (18°19ʹ21,34”N, 66°35ʹ15,67”W), Tanamá River (18°24ʹ39,05”N, 66°42ʹ54,54”W), Jobos Ravine (18°19ʹ18,03”N, 66°40ʹ46,04”W), Great River of Manatí (18°24ʹ31,31”N, 66°29ʹ46,04”W), Cañabón River (18°13ʹ24,69”N, 66°20ʹ17,26”W), Bauta River (18°17ʹ52,09”N, 66°27ʹ35,69”W), Cialitos River (18°17ʹ09,70”N, 66°30ʹ53,76”W), Maravilla River (18°21ʹ05,76”N, 66°17ʹ50,17”W), Unibón River (18°20ʹ36,43”N, 66°22ʹ50,04”W), Barranquita River (18°10ʹ24,90”N, 66°17ʹ53,82”W), La Zapatera Ravine (18°07ʹ23,70”N, 66°05ʹ07,65”W), and Río Piedras River (18°24ʹ00,98”N, 66°03ʹ42,58”W).

References [Citation3,Citation36,Citation44].

Xiphophorus maculatus (Günther, 1866)

Distribution

North and Central America: Ciudad Veracruz, Mexico to northern Belize.

Puerto Rico localities: found in several drainages around the island.

References [Citation15,Citation36,Citation40].

Order Mugiliformes

Family Mugilidae Jarocki, 1822

Agonostomus (Bancroft in Griffith and Smith, 1834)

Distribution

North to South America: North Carolina, Florida, Louisiana and Texas in the USA to Colombia and Venezuela, including the West Indies.

Puerto Rico localities: Canóvanas River (18°23ʹ48,18”N, 65°54ʹ44,89”W), Herrera River (18°33ʹ01,20”N, 65°51ʹ50,27”W), Tabonuco Ravine (18°21ʹ15,53”N, 65°28ʹ09,18”W), Mameyes River (18°19ʹ26,57”N, 65°44ʹ55,89”W), Sabana River (18°15ʹ44,05”N, 65°47ʹ39,13”W), Pitahaya River (18°21ʹ53,73”N, 65°43ʹ06,53”W), Juan Martín River (18°21ʹ07,85”N, 65°41ʹ00,90”W), Juan Diego Ravine (18°18ʹ27,67”N, 65°46ʹ08,63”W), Rincón Ravine (18°17ʹ18,25”N, 65°41ʹ37,67”W), Humacao River (18°09ʹ03,55”N, 65°51ʹ55,77”W), Maunabo River (18°00ʹ12,59”N, 65°54ʹ13,65”W), Majada River (18°02ʹ30,63”N, 66°12ʹ36,38”W), Pastillo River (18°02ʹ19,84”N, 66°39ʹ54,84”W), Tallaboa River (18°02ʹ17,33”N, 66°43ʹ17,40”W), Macaná River (18°00ʹ51,57”N, 66°45ʹ55,35”W), Guayanilla River (18°18ʹ12,33”N, 66°47ʹ55,91”W), Yauco River (17°59ʹ23,53”N, 66°50ʹ24,92”W), Yagüez River (18°12ʹ26,80”N, 67°07ʹ07,81”W), Blanco River (18°13ʹ46,94”N, 65°47ʹ09,12”W), Prieto River (18°15ʹ19,81”N, 65°46ʹ52,57”W), Great River of Añasco (18°16ʹ28,28”N, 67°06ʹ47,09”W), Casey River (18°16ʹ10,42”N, 67°07ʹ07,29”W), Salada Ravine (18°21ʹ04,74”N, 67°01ʹ32,95”W), Dulce Ravine (18°23ʹ05,35”N, 67°05ʹ42,48”W), Toro Negro River (18°13ʹ49.25”N, 66°30ʹ44,99”W), Cialitos River (18°17ʹ09,70”N, 66°30ʹ53,76”W), Río Piedras River (18°24ʹ00,98”N, 66°03ʹ42,58”W), Tortuguero lagoon (18°27ʹ50,37”N, 66°26ʹ36,91”W), Great River of Añasco (18°16ʹ28,28”N, 67°06ʹ47,09”W), Bucarabones River (18°12ʹ59,52”N, 66°56ʹ35,08”W), Great River of Loiza (18°23ʹ48,19”N, 65°54ʹ44,89”W), Great River of Arecibo (18°24ʹ06,07”N, 66°41ʹ27,10”W), Canóvanas River (18°23ʹ48,18”N, 65°54ʹ44,89”W) and Canovanillas River (18°19ʹ17,07”N, 65°54ʹ13,36”W).

References [Citation3,Citation16,Citation31,Citation33,Citation36,Citation45].

Remarks: I-00095, 7 organisms collected; I-00096, 2 orgs. collected on 14 March 1969; I-00097, 2 orgs collected on 22 February 1969; I-00098, 30 orgs. collected on 25 March 1969; I-00099, 5 orgs. collected on 14 March 1969; and I-00100, 70 orgs. collected on 14 February 1969.

Order PerciformesFamily Centrarchidae Bleeker, 1859Micropterus chattahoochae Baker, Johnston and Blanton, 2013

Distribution

Endemic to the Chattahoochee River system on the Piedmont in the west part of Georgia (USA).

Puerto Rico localities: Rosario River (18°07ʹ31,99”N, 67°07ʹ23,65”W).

References [Citation36,Citation46].

Micropterus salmoides (Lacepède, 1802)

Distribution

North America: St. Lawrence, Great Lakes, Hudson Bay (Red River), and Mississippi River basins; Atlantic drainages from North Carolina to Florida and northern Mexico. The species has been introduced widely as a game fish and is now cosmopolitan.

Puerto Rico localities: La Plata River (18°08ʹ14,07”N, 66°12ʹ27,07”W), Yauco River (17°59ʹ23,53”N, 66°50ʹ24,92”W), Dulce Ravine (18°23ʹ05,35”N, 67°05ʹ42,48”W), Great River of Manatí (18°24ʹ31,31”N, 66°29ʹ46,04”W), Rosario River (18°07ʹ31,99”N, 67°07ʹ23,65”W) and Río Piedras River (18°24ʹ00,98”N, 66°03ʹ42,58”W). This species is also present in most of the island reservoirs.

References [Citation3,Citation16,Citation34].

Lepomis auritus (Linnaeus, 1758)

Distribution

North America: Eastern Rivers of USA and Canada.

Puerto Rico localities: Cañas River (18°17ʹ22,84”N, 66°03ʹ58,96”W), Great River of Manatí (18°24ʹ31,31”N, 66°29ʹ46,04”W), Barranquita River (18°10ʹ24,90”N, 66°17ʹ53,82”W), La Zapatera Ravine (18°07ʹ23,70”N, 66°05ʹ07,65”W), Carite (18°04ʹ44,13”N, 66°06ʹ00,05”W), Cidra (18°11ʹ38,75”N, 66°08ʹ18,24”W), Dos Bocas (18°19ʹ57,68”N, 66°40ʹ05,12”W), Guayabal (18°05ʹ44,53”N, 66°30ʹ14,13”W), Cerrillos (18°05ʹ49,92”N, 66°34ʹ43,83”W), Luchetti (18°05ʹ73,80”N, 66°52ʹ09,03”W), La Plata (18°20ʹ04,89”N, 66°14ʹ08,25”W), Guajataca (18°23ʹ26,86”N, 66°55ʹ25,94”W), Guayo (18°11ʹ56,02”N, 66°50ʹ01,79”W), Patillas (18°01ʹ27,38”N, 66°01ʹ23,76”W) reservoirs, and Tortuguero Lagoon (18°27ʹ50,37”N, 66°26ʹ36,91”W).

References [Citation3,Citation34].

Lepomis macrochirus (Rafinesque, 1819)

Distribution

North America: The Great Lakes and Mississippi river basin; from Quebec to northern Mexico.

Puerto Rico localities: Garzas (18°08ʹ12,96”N, 66°44ʹ38,48”W), Guayo (18°11ʹ56,02”N, 66°50ʹ01,79”W), Patillas (18°01ʹ27,38”N, 66°01ʹ23,76”W), Cerrillos (18°05ʹ49,92”N, 66°34ʹ43,83”W), Luchetti (18°05ʹ73,80”N, 66°52ʹ09,03”W), and La Plata (18°20ʹ04,89”N, 66°14ʹ08,25”W) reservoirs.

References [Citation15,Citation34].

Lepomis microlophus (Günther, 1859)

Distribution

North America: Savannah River in South Carolina to Nueces River in Texas, Mississippi River basin to southern Indiana and Illinois in the USA.

Puerto Rico localities: Tortuguero Lagoon (18°27ʹ50,37”N, 66°26ʹ36,91”W), Garzas (18°08ʹ12,96”N, 66°44ʹ38,48”W), Cidra (18°11ʹ38,75”N, 66°08ʹ18,24”W), Carite (18°04ʹ44,13”N, 66°06ʹ00,05”W), Toa Vaca (18°06ʹ09,99”N, 66°28ʹ57,91”W), Guayabal (18°05ʹ44,53”N, 66°30ʹ14,13”W), Patillas (18°01ʹ27,38”N, 66°01ʹ23,76”W), Guayo (18°11ʹ56,02”N, 66°50ʹ01,79”W), Guajataca (18°23ʹ26,86”N, 66°55ʹ25,94”W), Cerrillos (18°05ʹ49,92”N, 66°34ʹ43,83”W), Luchetti (18°05ʹ73,80”N, 66°52ʹ09,03”W), and La Plata (18°20ʹ04,89”N, 66°14ʹ08,25”W) reservoirs.

References [Citation16,Citation34,Citation47].

Family Cichlidae Bonaparte, 1835

Archocentrus nigrofasciatus (Günther, 1867)

Distribution

Its range extends through Nicaragua and at least into Costa Rica; also found in continental U.S.A and Hawaii.

Puerto Rico localities: Patillas Canal (17°58ʹ40,63”N, 66°08ʹ56,52”W), Cañas (18°17ʹ22,84”N, 66°03ʹ58,96”W), Guaynabo (18°21ʹ59,78”N, 66°06ʹ41,32”W), and Yunes (18°19ʹ21,34”N, 66°35ʹ15,67”W) rivers, Also found in Loiza (18°18ʹ54,98”N, 66°01ʹ14,52”W), Caonillas (18°16ʹ28,90”N, 66°39ʹ10,30”W), Dos Bocas (18°19ʹ57,68”N, 66°40ʹ05,12”W), and Toa Vaca (18°06ʹ09,99”N, 66°28ʹ57,91”W) reservoirs.

References [Citation3,Citation36,Citation48,Citation49].

Amphilophus citrinellus (Günther, 1864)

Distribution

Central America: Atlantic slope of Nicaragua and Costa Rica (San Juan River drainage, including Lakes Nicaragua, Managua, Masaya and Apoyo).

Puerto Rico localities: Cañaboncito (18°12ʹ58,94”N, 66°04ʹ14,69”W), Cañas (18°17ʹ22,84”N, 66°03ʹ58,96”W), Cañabón (18°13ʹ24,69”N, 66°20ʹ17,26”W), and Río Piedras (18°24ʹ00,98”N, 66°03ʹ42,58”W) rivers. Also found in Guajataca (18°23ʹ26,86”N, 66°55ʹ25,94”W), Loiza (18°18ʹ54,98”N, 66°01ʹ14,52”W), Dos Bocas (18°19ʹ57,68”N, 66°40ʹ05,12”W), Cidra (18°11ʹ38,75”N, 66°08ʹ18,24”W), Caonillas (18°16ʹ28,90”N, 66°39ʹ10,30”W), Guayabal (18°05ʹ44,53”N, 66°30ʹ14,13”W), and La Plata (18°20ʹ04,89”N, 66°14ʹ08,25”W) reservoirs.

References [Citation36].

Amphilophus labiatus (Günther, 1864)

Distribution

Central America: Atlantic slope of Nicaragua, in Lakes Nicaragua and Managua.

Puerto Rico localities: Guaynabo River (18°21ʹ59,78”N, 66°06ʹ41,32”W), Great River of Loiza (18°23ʹ48,19”N, 65°54ʹ44,89”W), Caonillas (18°16ʹ28,90”N, 66°39ʹ10,30”W), and Dos Bocas (18°19ʹ57,68”N, 66°40ʹ05,12”W) reservoirs.

References [Citation36,Citation50].

Astronotus ocellatus (Agassiz in Spix and Agassiz, 1831)

Distribution

South America: Amazon River basin in Peru, Colombia and Brazil; French Guiana, and Argentina.

Puerto Rico localities: Aibonito farm pond, Bayamón River (18°22ʹ11,03”N, 66°8ʹ49,69”W), tributary of Guaynabo River (18°12ʹ20,52”N, 66°03ʹ48,99”W), Tortuguero Lagoon (18°27ʹ50,37”N, 66°26ʹ36,91”W), Loiza (18°18ʹ54,98”N, 66°01ʹ14,52”W), Las Curias (18°20ʹ29,74”N, 66°02ʹ53,85”W), Guajataca (18°23ʹ26,86”N, 66°55ʹ25,94”W), La Plata (18°20ʹ04,89”N, 66°14ʹ08,25”W), Comerio (18°15ʹ35,98”N, 66°12ʹ19,81”W), Cidra (18°11ʹ38,75”N, 66°08ʹ18,24”W) reservoirs.

References [Citation15,Citation34,Citation36,Citation51,Citation52].

Cichla ocellaris (Bloch and Schneider, 1801)

Distribution

South America: Marowijne drainage in Suriname and French Guiana to the Essequibo drainage in Guyana.

Puerto Rico localities: Loiza (18°18ʹ54,98”N, 66°01ʹ14,52”W), Dos Bocas (18°19ʹ57,68”N, 66°40ʹ05,12”W), Caonillas (18°16ʹ28,90”N, 66°39ʹ10,30”W), Carite (18°04ʹ44,13”N, 66°06ʹ00,05”W), Patillas (18°01ʹ27,38”N, 66°01ʹ23,76”W), Cidra (18°11ʹ38,75”N, 66°08ʹ18,24”W), Guayabal (18°05ʹ44,53”N, 66°30ʹ14,13”W), La Plata (18°20ʹ04,89”N, 66°14ʹ08,25”W), Luchetti (18°05ʹ73,80”N, 66°52ʹ09,03”W), and Guajataca (18°23ʹ26,86”N, 66°55ʹ25,94”W) reservoirs.

References [Citation36,Citation53].

Herichthys cyanoguttatum (Baird and Girard, 1854)

Distribution

North America: originally restricted to the lower Rio Grande drainage in Texas, USA and south to northeastern Mexico. Introduced on Edwards Plateau of central Texas and central peninsular Florida, USA, and Verde River basin (La Media Luna region), Mexico.

Puerto Rico localities: Loiza (18°18ʹ54,98”N, 66°01ʹ14,52”W) reservoir.

References [Citation34,Citation36,Citation54].

Oreochromis aureus (Steindachner, 1864)

Distribution

Africa and Eurasia: Jordan Valley, Lower Nile, Chad Basin, Benue, middle and upper Niger, Senegal River. Introduced in the oasis of Azraq (Jordan), warm water ponds of USA, South and Central America and South East Asia.

Puerto Rico localities: Widespread throughout the island (rivers and reservoirs).

References [Citation36,Citation55].

Oreochromis mossambicus (Peters, 1852)

Distribution

Africa: Lower Zambezi, Lower Shiré and coastal plains from Zambezi delta to Algoa Bay. Occurs southwards to the Brak River in the Eastern Cape and in the Transvaal in the Limpopo system.

Puerto Rico localities: drainage canals, farm ponds, reservoirs and lagoons, though not everywhere. Cañas River (18°17ʹ22,84”N, 66°03ʹ58,96”W), Canovanillas River (18°19ʹ17,07”N, 65°54ʹ13,36”W), Juan Martín River (18°21ʹ07,85”N, 65°41ʹ00,90”W), Guayanés River (18°04ʹ12,51”N, 65°50ʹ32,70”W), Caño Santiago (18°03ʹ29,08”N, 65°49ʹ32,71”W), Majada River (18°02ʹ30,63”N, 66°12ʹ36,38”W), Guayanilla River (18°18ʹ12,33”N, 66°47ʹ55,91”W), Yauco River (17°59ʹ23,53”N, 66°50ʹ24,92”W), Loco River (18°00ʹ53,10”N, 66°52ʹ33,10”W), Prieto River (18°15ʹ19,81”N, 65°46ʹ52,57”W), Guatemala River (18°20ʹ35,75”N, 66°59ʹ59,16”W), Cialitos River (18°17ʹ09,70”N, 66°30ʹ53,76”W), Maravilla River (18°21ʹ05,76”N, 66°17ʹ50,17”W), Morovis River (18°20ʹ57,45”N, 66°23ʹ10,50”W), Unibón River (18°20ʹ36,43”N, 66°22ʹ50,04”W), Barranquita River (18°10ʹ24,90”N, 66°17ʹ53,82”W), La Zapatera Ravine (18°07ʹ23,70”N, 66°05ʹ07,65”W), Guaynabo River (18°21ʹ59,78”N, 66°06ʹ41,32”W), Río Piedras River (18°24ʹ00,98”N, 66°03ʹ42,58”W), and Loiza Reservoir (18°18ʹ54,98”N, 66°01ʹ14,52”W).

References [Citation3,Citation16,Citation55].

Remarks: I-00119, one organism collected on 20 January 1975; I-00120, one org. collected on 03/14/1975; and I-00121, one org. collected on 14 March 1975.

Oreochromis niloticus (Linnaeus, 1758)

Distribution

Widely introduced for aquaculture. Naturally occurring in coastal rivers of Israel, Nile basin, Ethiopian lakes, and West Africa.

Puerto Rico localities: Great River of Loiza (18°23ʹ48,19”N, 65°54ʹ44,89”W), Cañas River (18°17ʹ22,84”N, 66°03ʹ58,96”W), Canovanillas River (18°19ʹ17,07”N, 65°54ʹ13,36”W), and Blanco River (18°13ʹ46,94”N, 65°47ʹ09,12”W).

References [Citation3,Citation55].

Parachromis managuensis (Günther, 1867)

Distribution

Central America: Atlantic slope from the Ulua River (Honduras) to the Matina River in Costa Rica.

Puerto Rico localities: Bayamón River (18°22ʹ11,03”N, 66°8ʹ49,69”W), Guaynabo River (18°21ʹ59,78”N, 66°06ʹ41,32”W), Loiza (18°18ʹ54,98”N, 66°01ʹ14,52”W), Cidra (18°11ʹ38,75”N, 66°08ʹ18,24”W), Guajataca (18°23ʹ26,86”N, 66°55ʹ25,94”W), Dos Bocas (18°19ʹ57,68”N, 66°40ʹ05,12”W), and La Plata (18°20ʹ04,89”N, 66°14ʹ08,25”W) reservoirs.

References [Citation36,Citation54].

Thorichthys meeki Brind, 1918

Distribution

Central America: Atlantic slope in the Usumacinta River drainage, the Belize River drainage, and near Progreso in Mexico, Guatemala, and Belize.

Puerto Rico localities: Dos Bocas (18°19ʹ57,68”N, 66°40ʹ05,12”W), La Plata (18°20ʹ04,89”N, 66°14ʹ08,25”W), Caonillas (18°16ʹ28,90”N, 66°39ʹ10,30”W), Guayabal (18°05ʹ44,53”N, 66°30ʹ14,13”W), and Loiza (18°18ʹ54,98”N, 66°01ʹ14,52”W) reservoirs (Grana 2007).

References [Citation36,Citation56].

Tilapia rendalli (Boulenger, 1897)

Distribution

Africa: from the middle Congo River basin up to the upper Lualaba and the Bangweulu area. Also, in Lake Malawi, Zambesi, coastal areas from Zambesi Delta to Natal, Okavango, Cunene, Limpopo, Malagarasi and Lake Tanganyika. Introduced elsewhere, usually for weed control and aquaculture.

Puerto Rico localities: Bayamón River (18°22ʹ11,03”N, 66°8ʹ49,69”W), Guaynabo River (18°21ʹ59,78”N, 66°06ʹ41,32”W), Cañas River (18°17ʹ22,84”N, 66°03ʹ58,96”W). Very abundant in most of the island reservoirs.

References [Citation3,Citation57].

Vieja melanura (Günther, 1862)

Distribution

Central America: Atlantic slope, in the Usumacinta River drainage in Mexico, Guatemala and Belize.

Puerto Rico localities: Guajataca (18°23ʹ26,86”N, 66°55ʹ25,94”W), Guayo (18°11ʹ56,02”N, 66°50ʹ01,79”W) and La Plata (18°20ʹ04,89”N, 66°14ʹ08,25”W) reservoirs.

References [Citation36,Citation56].

Family Eleotridae Bonaparte, 1835

Dormitator maculatus (Bloch, 1792)

Distribution

Western Atlantic from North Carolina south along the USA, Bahamas, throughout the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea to southeastern Brazil.

Puerto Rico localities: Widespread throughout the island, but only in rivers, not present in freshwater reservoirs.

References [Citation17,Citation36,Citation47,Citation58].

Eleotris perniger (Cope, 1871)

Distribution

Northwest to western Central Atlantic: Bermuda, Bahamas, South Carolina and northern Gulf of Mexico in the USA to southeastern Brazil.

Puerto Rico localities: Tabonuco Ravine (18°21ʹ15,53”N, 65°28ʹ09,18”W), Mameyes River (18°19ʹ26,57”N, 65°44ʹ55,89”W), Sabana River (18°15ʹ44,05”N, 65°47ʹ39,13”W), Pitahaya River (18°21ʹ53,73”N, 65°43ʹ06,53”W), Juan Martín River (18°21ʹ07,85”N, 65°41ʹ00,90”W), Juan Diego Ravine (18°18ʹ27,67”N, 65°46ʹ08,63”W), Rincón Ravine (18°17ʹ18,25”N, 65°41ʹ37,67”W), Guayanés River (18°04ʹ12,51”N, 65°50ʹ32,70”W), Caño Santiago (18°03ʹ29,08”N, 65°49ʹ32,71”W), Maunabo River (18°00ʹ12,59”N, 65°54ʹ13,65”W), Guayanilla River (18°18ʹ12.33”N, 66°47ʹ55.91”W), Yauco River (17°59ʹ23,53”N, 66°50ʹ24,92”W), Los Llanos Ravine (18°01ʹ44,65”N, 67°06ʹ49,65”W), Yagüez River (18°12ʹ26,80”N, 67°07ʹ07,81”W), Salada Ravine (18°21ʹ04,74”N, 67°01ʹ32,95”W), Dulce Ravine (18°23ʹ05,35”N, 67°05ʹ42,48”W), Cialitos River (18°17ʹ09,70”N, 66°30ʹ53,76”W), and Río Piedras River (18°24ʹ00,98”N, 66°03ʹ42,58”W).

References [Citation3,Citation36,Citation58].

Gobiomorus dormitor (Lacepède, 1800)

Distribution

Western Central Atlantic, southern Florida and southern Texas in the USA to eastern Brazil.

Puerto Rico localities: Reported in all rivers of Puerto Rico, also found in Tortuguero Lagoon (18°27ʹ50,37”N, 66°26ʹ36,91”W), Loiza (18°18ʹ54,98”N, 66°01ʹ14,52”W), Melania (17°58ʹ42,55”N, 66°08ʹ35,92”W), Patillas (18°01ʹ27,38”N, 66°01ʹ23,76”W), and Carite (18°04ʹ44,13”N, 66°06ʹ00,05”W) reservoirs, Canóvanas River (18°23ʹ48,18”N, 65°54ʹ44,89”W), Herrera River (18°33ʹ01,20”N, 65°51ʹ50,27”W), Tabonuco Ravine (18°21ʹ15,53”N, 65°28ʹ09,18”W), Mameyes River (18°19ʹ26,57”N, 65°44ʹ55,89”W), Sabana River (18°15ʹ44,05”N, 65°47ʹ39,13”W), Pitahaya River (18°21ʹ53,73”N, 65°43ʹ06,53”W), Juan Martín River (18°21ʹ07,85”N, 65°41ʹ00,90”W), Juan Diego Ravine (18°18ʹ27,67”N, 65°46ʹ08,63”W), Rincón Ravine (18°17ʹ18,25”N, 65°41ʹ37,67”W), Guayanés River (18°04ʹ12,51”N, 65°50ʹ32,70”W), Caño Santiago (18°03ʹ29,08”N, 65°49ʹ32,71”W), Maunabo River (18°00ʹ12,59”N, 65°54ʹ13,65”W), Majada River (18°02ʹ30,63”N, 66°12ʹ36,38”W), Pastillo River (18°02ʹ19,84”N, 66°39ʹ54,84”W), Tallaboa River (18°02ʹ17,33”N, 66°43ʹ17,40”W), Guayanilla River (18°18ʹ12,33”N, 66°47ʹ55,91”W), Yagüez River (18°12ʹ26,80”N, 67°07ʹ07,81”W), Blanco River (18°13ʹ46,94”N, 65°47ʹ09,12”W), Prieto River (18°15ʹ19,81”N, 65°46ʹ52,57”W), Salada Ravine (18°21ʹ04,74”N, 67°01ʹ32,95”W), Dulce Ravine (18°23ʹ05,35”N, 67°05ʹ42,48”W), Toro Negro River (18°13ʹ49.25”N, 66°30ʹ44,99”W), Cialitos River (18°17ʹ09,70”N, 66°30ʹ53,76”W), Río Piedras River (18°24ʹ00,98”N, 66°03ʹ42,58”W), Guayanés River (18°04ʹ12,51”N, 65°50ʹ32,70”W), and Guajataca River (18°26ʹ52,79”N, 66°57ʹ45,94”W).

References [Citation3,Citation16,Citation36,Citation58,Citation59].

Remarks: I-00176, 3 orgs. collected on 31 March 1969; I-00177, 2 orgs. collected on 14 March 1969; I-00178, 2 orgs. collected on 07 March 1969; I-00179, 1 org. collected on 21 March 1969; I-00180, 10 orgs. collected on 06 March 1969; I-00181, 3 orgs. collected on 13 February 1969; I-00182, 1 org. collected on 20 November 1969; I-00183, 4 orgs. collected on 07 March 1969; I-00185, 1 org. collected on 22 February 1969; I-00186, 4 orgs. collected on 22 February 1969; I-00187, 19 orgs. collected on 22 February 1969; I-00188, 4 organisms collected on 28 March 1969; I-00184, 7 orgs. collected on 08 February 1969; I-00189, 4 orgs. collected on 25 April 1976, and I-00190, 40 orgs. collected on 01/26/2005.

Family Gobiidae Cuvier, 1816

Awaous banana (Valenciennes in Cuvier and Valenciennes, 1837)

Distribution

North, Central and South America: northern Florida, USA southward through the Greater and the Lesser Antilles to Trinidad and Tobago, and from Tamaulipas, Mexico southward to Caracas, Venezuela; central Baja California Sur and Sonora, Mexico southward to Tumbes, Peru.

Puerto Rico localities: Canovanillas River (18°19ʹ17,07”N, 65°54ʹ13,36”W), Canóvanas River (18°23ʹ48,18”N, 65°54ʹ44,89”W), Herrera River (18°33ʹ01,20”N, 65°51ʹ50,27”W), Tabonuco Ravine (18°21ʹ15,53”N, 65°28ʹ09,18”W), Mameyes River (18°19ʹ26,57”N, 65°44ʹ55,89”W), Sabana River (18°15ʹ44,05”N, 65°47ʹ39,13”W), Pitahaya River (18°21ʹ53,73”N, 65°43ʹ06,53”W), Juan Martín River (18°21ʹ07,85”N, 65°41ʹ00,90”W), Juan Diego Ravine (18°18ʹ27,67”N, 65°46ʹ08,63”W), Guayabal Reservoir (18°05ʹ44,53”N, 66°30ʹ14,13”W), Rincón Ravine (18°17ʹ18,25”N, 65°41ʹ37,67”W), Humacao River (18°09ʹ03,55”N, 65°51ʹ55,77”W), Guayanés River (18°04ʹ12,51”N, 65°50ʹ32,70”W), Caño Santiago (18°03ʹ29,08”N, 65°49ʹ32,71”W), Maunabo River (18°00ʹ12,59”N, 65°54ʹ13,65”W), Majada River (18°02ʹ30,63”N, 66°12ʹ36,38”W), Descalabrado River (18°03ʹ57,07”N, 66°25ʹ48,19”W), Cañas River (18°17ʹ22,84”N, 66°03ʹ58,96”W), Pastillo River (18°02ʹ19,84”N, 66°39ʹ54.84”W), Tallaboa River (18°02ʹ17,33”N, 66°43ʹ17,40”W), Macaná River (18°00ʹ51,57”N, 66°45ʹ55,35”W), Guayanilla River (18°18ʹ12,33”N, 66°47ʹ55,91”W), Yauco River (17°59ʹ23,53”N, 66°50ʹ24,92”W), Loco River (18°00ʹ53,10”N, 66°52ʹ33,10”W), Yagüez River (18°12ʹ26,80”N, 67°07ʹ07,81”W), Blanco River (18°13ʹ46,94”N, 65°47ʹ09,12”W), Prieto River (18°15ʹ19,81”N, 65°46ʹ52,57”W), Great River of Añasco (18°16ʹ28,28”N, 67°06ʹ47,09”W), Casey River (18°16ʹ10,42”N, 67°07ʹ07,29”W), Guatemala River (18°20ʹ35,75”N, 66°59ʹ59,16”W), Salada Ravine (18°21ʹ04,74”N, 67°01ʹ32,95”W), Dulce Ravine (18°23ʹ05,35”N, 67°05ʹ42,48”W), tributaries to Culebrinas River, Toro Negro River (18°13ʹ49.25”N, 66°30ʹ44,99”W), Cialitos River (18°17ʹ09,70”N, 66°30ʹ53,76”W), Unibón River (18°20ʹ36,43”N, 66°22ʹ50,04”W), Guaynabo River (18°21ʹ59,78”N, 66°06ʹ41,32”W), and Río Piedras River (18°24ʹ00,98”N, 66°03ʹ42,58”W).

References: 3,36, Watson (1996).

Remarks: I-00194, one organism collected on 22 March 1976; I-00195, one org. collected on 28 March 1969; I-00196, two orgs. collected on 22 February 1969; and I-00197, one org. collected on 22 February 1969. All these specimens were classified as Awaous sp.

Sicydium buscki Evermann and Clark, 1906

Distribution

Cuba, Dominican Republic, and Puerto Rico.

Puerto Rico localities: Maricao, Arecibo, and Aguadilla municipalities.

References [Citation21,Citation53,Citation60,Citation61].

Sicydium plumieri (Bloch, 1786)

Distribution

The Greater and Lesser Antilles, South of Cuba, and Panama.

Puerto Rico localities: Canovanillas River (18°19ʹ17,07”N, 65°54ʹ13,36”W), Canóvanas River (18°23ʹ48,18”N, 65°54ʹ44,89”W), Herrera River (18°33ʹ01,20”N, 65°51ʹ50,27”W), Espíritu Santo River (18°21ʹ54,37”N, 65°48ʹ55,44”W), Tabonuco Ravine (18°21ʹ15,53”N, 65°28ʹ09,18”W), Sabana River (18°15ʹ44,05”N, 65°47ʹ39,13”W), Juan Martín River (18°21ʹ07,85”N, 65°41ʹ00,90”W), Juan Diego Ravine (18°18ʹ27,67”N, 65°46ʹ08,63”W), Majada River (18°02ʹ30,63”N, 66°12ʹ36,38”W), Descalabrado River (18°03ʹ57,07”N, 66°25ʹ48,19”W), Cañas River (18°17ʹ22,84”N, 66°03ʹ58,96”W), Pastillo River (18°02ʹ19,84”N, 66°39ʹ54.84”W), Tallaboa River (18°02ʹ17,33”N, 66°43ʹ17,40”W), Macaná River (18°00ʹ51,57”N, 66°45ʹ55,35”W), Guayanilla River (18°18ʹ12.33”N, 66°47ʹ55.91”W), Loco River (18°00ʹ53,10”N, 66°52ʹ33,10”W), Yagüez River (18°12ʹ26,80”N, 67°07ʹ07,81”W), Blanco River (18°13ʹ46,94”N, 65°47ʹ09,12”W), Prieto River (18°15ʹ19.81”N, 65°46ʹ52.57”W), Great River of Añasco (18°16ʹ28,28”N, 67°06ʹ47,09”W), Fría Ravine (18°14ʹ07,84”N, 66°56ʹ24,28”W), Casey River (18°16ʹ10,42”N, 67°07ʹ07,29”W), Dulce Ravine (18°23ʹ05,35”N, 67°05ʹ42,48”W), Tanamá River (18°24ʹ39,05”N, 66°42ʹ54,54”W), Great River of Manatí (18°24ʹ31,31”N, 66°29ʹ46,04”W), Bauta River (18°17ʹ52,09”N, 66°27ʹ35,69”W), Cialitos River (18°17ʹ09,70”N, 66°30ʹ53,76”W), Toro Negro River (18°13ʹ49,25”N, 66°30ʹ44,99”W), Unibón River (18°20ʹ36,43”N, 66°22ʹ50,04”W), and Río Piedras River (18°24ʹ00,98”N, 66°03ʹ42,58”W).

References [Citation3,Citation21,Citation31,Citation36,Citation54,Citation61].

Remarks: I-000203, 1 organism collected on 22 May 1998; and I-00204, 26 orgs. collected on 27 April 2000.

Sicydium punctatum Perugia, 1896

Distribution

Caribbean coast of Venezuela, Dominica, Jamaica, Martinique, Puerto Rico, Trinidad and Tobago, and Panama.

Puerto Rico localities: Great River of Añasco (18°16ʹ28,28”N, 67°06ʹ47,09”W) and Blanco River (18°13ʹ46,94”N, 65°47ʹ09,12”W).

References [Citation21,Citation53,Citation61].

Order Siluriformes

Family Clariidae Bonaparte, 1846

Clarias gariepinus (Burchell, 1822)

Distribution

The species is native to most of the African continent and small areas of Asia in Israel, Syria and the south of Turkey. The African catfish has been introduced in at least 37 countries of Africa, Europe, Asia and America, mainly for aquaculture, with negative impacts in freshwater and brackish ecosystems.

Puerto Rico localities: Patillas Canal (17°58ʹ40,63”N, 66°08ʹ56,52”W).

References [Citation23,Citation62].

Remarks: MZUPRRP-I-936 and MZUPRRP-I-937, 2 organisms collected in 2018.

Family Ictaluridae Gill, 1861Ameiurus catus (Linnaeus, 1758)

Distribution

North America: Rivers of the Atlantic coastal states of the USA from Florida to New York.

Puerto Rico localities: Dos Bocas Reservoir (18°19ʹ57,68”N, 66°40ʹ05,12”W).

References [Citation16,Citation36,Citation63].

Ameiurus nebulosus (Lesueur, 1819)

Distribution

North America: Atlantic and Gulf Slope drainages from Nova Scotia and New Brunswick in Canada to Mobile Bay in Alabama in the USA, and St. Lawrence-Great Lakes, Hudson Bay and Mississippi River basins from Quebec west to Saskatchewan in Canada and south to Louisiana, USA. Several countries report adverse ecological impact after the introduction. Asia: Iran and Turkey.

Puerto Rico localities: Melania (17°58ʹ42,55”N, 66°08ʹ35,92”W), Comerío (18°15ʹ29,50”N, 66°12ʹ17,59”W), Carite (18°04ʹ44,13”N, 66°06ʹ00,05”W), Dos Bocas (18°19ʹ57,68”N, 66°40ʹ05,12”W), Toa Vaca (18°06ʹ09,99”N, 66°28ʹ57,91”W), Patillas (18°01ʹ27,38”N, 66°01ʹ23,76”W), Caonillas (18°16ʹ28,90”N, 66°39ʹ10,30”W), Guayabal (18°05ʹ44,53”N, 66°30ʹ14,13”W) reservoirs, and La Plata River (18°08ʹ14,07”N, 66°12ʹ27,07”W).

References [Citation16,Citation36].

Ictalurus punctatus (Rafinesque, 1818)

Distribution

Central drainages of the United States to southern Canada and northern Mexico; also introduced in Europe, the Russian Federation, Cuba, and portions of Latin America.

Puerto Rico localities: Dos Bocas (18°19ʹ57,68”N, 66°40ʹ05,12”W), Loiza (18°18ʹ54,98”N, 66°01ʹ14,52”W), Patillas (18°01ʹ27,38”N, 66°01ʹ23,76”W), Carite (18°04ʹ44,13”N, 66°06ʹ00,05”W), Caonillas (18°16ʹ28,90”N, 66°39ʹ10,30”W), Cidra (18°11ʹ38,75”N, 66°08ʹ18,24”W), Guayabal (18°05ʹ44,53”N, 66°30ʹ14,13”W), Guayo (18°11ʹ56,02”N, 66°50ʹ01,79”W), and Toa Vaca (18°06ʹ09,99”N, 66°28ʹ57,91”W) reservoirs, Cañas River (18°17ʹ22,84”N, 66°03ʹ58,96”W), Yauco River (17°59ʹ23,53”N, 66°50ʹ24,92”W), Loco River (18°00ʹ53,10”N, 66°52ʹ33,10”W), Blanco River (18°13ʹ46,94”N, 65°47ʹ09,12”W), Prieto River (18°15ʹ19,81”N, 65°46ʹ52.57”W), and the estuarine area of the Great River of Arecibo (18°27ʹ39,92”N, 66°42ʹ24,67”W).

References [Citation3,Citation16,Citation34,Citation36].

Remarks: I-00018, 1 organism collected on 11 August 1999.

Family Loricariidae Rafinesque, 1815Pterygoplichthys multiradiatus (Hancock, 1828)

Distribution

South America: Orinoco River basin, Argentina, Taiwan, mainland USA, and Hawaii.

Puerto Rico localities: Bayamón River (18°22ʹ11,03”N, 66°8ʹ49,69”W), Gurabo River (18°16ʹ01,09”N, 65°58ʹ55,04”W), Great River of Loiza (18°23ʹ48,19”N, 65°54ʹ44,89”W), Río Piedras River (18°24ʹ00,98”N, 66°03ʹ42,58”W), Guaynabo River (18°21ʹ59,78”N, 66°06ʹ41,32”W), Guanajibo River (18°06ʹ18,85”N, 67°03ʹ55,21”W), Loco River (18°00ʹ53,10”N, 66°52ʹ33,10”W), Patillas Canal (17°58ʹ40,63”N, 66°08ʹ56,52”W), Loiza (18°18ʹ54,98”N, 66°01ʹ14,52”W) and Dos Bocas reservoirs (18°19ʹ57,68”N, 66°40ʹ05,12”W), and Dorado Shrimp Farm.

References [Citation18,Citation36,Citation64].

Remarks: I-00020, 1 organism collected in 1999.

Pterygoplichthys pardalis (Castelnau, 1855)

Distribution

In South America, from lower, middle and upper Amazon River basin; also introduced to countries outside its native range.

Puerto Rico localities: Great River of Loiza River (18°23ʹ48,19”N, 65°54ʹ44,89”W), Cañas River (18°17ʹ22,84”N, 66°03ʹ58,96”W), Juan Martín River (18°21ʹ07,85”N, 65°41ʹ00,90”W), Yauco River (17°59ʹ23,53”N, 66°50ʹ24,92”W), La Zapatera Ravine (18°07ʹ23,70”N, 66°05ʹ07,65”W), Río Piedras River (18°24ʹ00,98”N, 66°03ʹ42,58”W), Loiza (18°18ʹ54,98”N, 66°01ʹ14,52”W), Dos Bocas (18°19ʹ57,68”N, 66°40ʹ05,12”W), Caonillas (18°16ʹ28,90”N, 66°39ʹ10,30”W), Patillas (18°01ʹ27,38”N, 66°01ʹ23,76”W), Cidra (18°11ʹ38,75”N, 66°08ʹ18,24”W), Guayabal (18°05ʹ44,53”N, 66°30ʹ14,13”W), Toa Vaca (18°06ʹ09,99”N, 66°28ʹ57,91”W), Carite (18°04ʹ44,13”N, 66°06ʹ00,05”W), Garzas (18°08ʹ12,96”N, 66°44ʹ38,48”W), and Cerrillos (18°05ʹ49,92”N, 66°34ʹ43,83”W) reservoirs.

References [Citation3,Citation64].

Family Pangasiidae Bleeker, 1858

Pangasius hypophthalmus (Sauvage, 1878)

Distribution

Asia: Mekong, Chao Phraya, and Maeklong basins.

Puerto Rico localities: Loiza Reservoir (18°18ʹ54,98”N, 66°01ʹ14,52”W), and Caribe Fisheries Inc. farm (18°01ʹ42,27”N, 66°58ʹ20,83”W) in Lajas.

References [Citation36,Citation65].

Discussion

We review the freshwater fish fauna of Puerto Rico and present an updated list of the species present in the island. We report all known sites occupied by each fish species that inhabit streams and freshwater reservoirs in the island (georeferenced when possible). Although 77 fish species have been reported for Puerto Rico [Citation3], we include only those species considered freshwater residents or species that spend most of their life cycle in freshwater. Consequently, we have excluded native fish such as Bathygobius soporator, Dormitor maculatus, Gerres cinereus, Kryptolebias marmoratus, Microphis brachyurus, Mugil cephalus, Mugil liza, Megalops atlanticus and Strongylura marina, all of which are occasionally found in freshwater streams, but primarily inhabit marine or estuarine ecosystems [Citation16]. One of the highlights of our study, and a source of concern, is the number of introduced species inhabiting streams and water reservoirs in Puerto Rico, compared to the pool of native species currently present on the islands. Less than 20% of the freshwater fish species are native.

The fast development of freshwater aquaculture in the past century has been a major factor responsible for the introduction of many exotic fish in mainland areas, and some islands [Citation66]. However, the dominance of aquarium species in our list and the lack of an established aquaculture industry in Puerto Rico indicate that the pet trade has been critical in the introduction of exotic freshwater fish. In the past, there were short-lived commercial tilapia farms established in Puerto Rico. For example, the Lajas Aquaculture Station and the Maricao Fish Hatchery operated for years [Citation67], with the Maricao Fish Hatchery still being operated today by the Department of Natural and Environmental Resources (D.N.E.R.). The introduction of most (62.6%) non-indigenous resident species in Puerto Rico is associated with the local aquarium and pet trade business, while the vector for the remainder non-native species is equivocal; however, we suspect the aquarium and pet trade market as the likely culprit.

The international fish trade is currently growing and represents an important source of revenue for many countries [Citation68,Citation69]. However, this brings with it the risk of release of live non-native freshwater fish outside their native range, which may have negative impacts on the populations of native species and the ecosystem services they provide. As with many introduced invasive species, the introduction of non-native freshwater fish may have unintended and unpredictable negative effects on local environments and currently represents one of the main threats against the survivorship and genetic integrity of native species populations [Citation70,Citation71]. Moreover, established exotic fish may introduce parasites and diseases, compete for or alter food resources and habitat dynamics, and prey upon native fish [Citation72]. The current freshwater fish community’s composition in Puerto Rico is not only a direct consequence of irresponsible and uninformed attitudes of pet owners but it is also due to the illegal introduction by local aquaculture farms. For example, the Jaguar Guapote Cichlid was introduced to Puerto Rico without the permission of the D.N.E.R by aquaculture farms to control tilapia overpopulation in the culture ponds. Once discovered, the D.N.E.R ordered the eradication of the fish, which was supposedly completed. However, the Jaguar Guapote appeared later in the Loiza Reservoir, which indicates other (geographic) sources are supplying the species into freshwater ecosystems.

The existence of another 128 freshwater fish sold locally as pets represents a serious threat and serves as a “potential pool” of non-native species that could be added to natural freshwater ecosystems in the future (See Appendix 1). Of all the species, those that belong to the family Cichlidae represent the most aggressive invaders, with 13 species established on the island and another 38 potential invasive species sold as pets (). The 2010 D.N.E.R Fisheries Regulations [Citation73] published a table with the aquarium species which are allowed for import into Puerto Rico. When we compare this list with our potential invasive species list, we noticed differences. For example, the Family Anguillidae has only one species in the D.N.E.R. list, but we also found another species of eel, Anguilla marmorata, sold as pets. Most alarming is that the Family Cichlidae has 113 species authorized by D.N.E.R to be sold as pets. Thirteen of those have escaped and established while another 39 potential cichlid invaders are still in the local market.

The negative impacts of exotic fish have not yet been thoroughly documented in Puerto Rico, but there are indications that impacts may be, indeed, serious. For example, Red devil cichlids (Amphilophus spp.) are known to be extremely aggressive predators and competitors. D.N.E.R has documented an inverse relationship between non-native sunfish (Lepomis sp.) and red devil abundances, but attributing sunfish decline to the introduction of invasive red devil cichlids is speculative since the evidence may be circumstantial [Citation74]. However, if there is such a relationship between the two non-indigenous species, then we could expect that if the red devil invades Puerto Rican rivers, they will potentially negatively impact the native freshwater fish community. Another species of concern is the armored catfish (Pterygoplichthys spp.) which could compromise shoreline stability by increasing riverbank erosion and suspended sediment loads in the reservoirs as a result of excavating nest burrows at high densities along shorelines [Citation75]. Armored catfish may also pose a threat to endangered brown pelicans (Pelecanus occidentalis), some of which have died from having catfish lodged in their throat by their spines [Citation18].

There are many different approaches to managing existing invasive species and avoiding new introductions. For example, managers and politicians should create an administrative bill that would establish public education programs and campaigns about the importance of avoiding the release of freshwater fish from aquaria and aquaculture in streams, channels, and reservoirs. New laws could also penalize releasing potential invasive fish with fines. More specific management of current populations of introduced fish, especially those that pose significant threats to Puerto Rico’s native fish and their ecosystems, should be prioritized. In order for management efforts to succeed, further research must be done to fill in the knowledge gaps in the distribution and ecology of introduced species. Efforts should prioritize native ecosystems with higher native fish diversity such as lowland streams and introduced species that are found at high abundances in these environments.

Author Contribution

Ruber Rodríguez-Barreras: fieldwork, writing, and web search.

Camille Zapata-Arroyo: study design, fieldwork, writing.

Wilfredo Falcón: study design, writing and web search.

María de Lourdes Olmeda: fieldwork and writing.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (63.5 KB)Acknowledgments

We want to thank the University of Puerto Rico in Bayamón, the Department of Natural and Environmental Resources (D.N.E.R) of Puerto Rico for supporting the field works and data collection. WFL and MLO thank the Wildlife and Sport Fish Restoration Program managed by the US Fish and Wildlife Service, for supporting scientific research on the freshwater ecosystems of Puerto Rico, and indirectly supporting this effort through Grant FW-16.1 (2019-2021), and others, awarded to D.N.E.R. Finally, we would like to thank Dr. James D. Ackerman (University of Puerto Rico), for his insightful suggestions, which helped improve the manuscript.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

References

- Winemiller KO, Agostinho AA, Caramaschi EP. Fish ecology in tropical streams. In D Dudgeon ed. Tropical stream ecology. San Diego: Academic Press. 2008. p. 107–146.

- March JG, Benstead JP, Pringle CM, et al. Damming tropical island streams: problems, solutions, and alternatives. BioScience. 2003;53:1069–1078.

- Kwak TJ, Cooney PB, Brown CH Fishery population and habitat assessment in Puerto Rico streams: phase 1 final report. Federal Aid in Sport Fish Restoration Project F-50 Final Report. Marine Resources Division, San Juan: Puerto Rico Department of Natural and Environmental Resources; 2007.

- McDowall RM. On amphidromy, a distinct form of diadromy in aquatic organisms. Fish Fisheries. 2007;8:1–13.

- Holmquist JG, Schmidt‐Gengenbach JM, Yoshioka BB. High dams and marine‐freshwater linkages: effects on native and introduced fauna in the Caribbean. Conserv Biol. 1998;2(3):621–630.

- Fitzsimons MJ, Parham JE, Nishimoto RT. Similarities in behavioral ecology among amphidromous and catadromous fishes on the oceanic islands of Hawaiʻi and Guam. Environ Biol Fish. 2002;65:123–129.

- Magurran AE. Threats to freshwater fish. Science. 2009;325:1215.

- Engman AC, Ramírez A. Fish assemblage structure in urban streams of Puerto Rico: the importance of reach-and catchment-scale abiotic factors. Hydrobiologia. 2012;693(1):141–155.

- Greathouse EA, Pringle CM, McDowell WH, et al. Indirect upstream effects of dams: consequences of migratory consumer extirpation in Puerto Rico. Ecol Appl. 2006;16(1):339–352.

- Walsh CJ, Roy AH, Feminella JW, et al. The urban stream syndrome: current knowledge and the search for a cure. J North Am Benthological Soc. 2005;24(3):706–723.

- Postel S, Carpenter S. Freshwater ecosystem services. In Gretchen C. Daily (ed.): Nature’s Services: societal dependence on natural ecosystems. Washington, D.C. and Corvelo, California: Island Press; 1997. p. 195–214.

- Wesley-Neal J, Lilyestrom CG, Kwak J. Factors influencing tropical Island freshwater fishes: species, status, and management implications in Puerto Rico. Fisheries. 2009;34(11):546–554.

- Cooney PB, Kwak TJ. Development of standard weight equations for Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico amphidromous fishes. North Am J Fish Manage. 2010;30(5):1203–1209.

- Simberloff D, Martin JL, Genovesi P. Impacts of biological invasions: what’s what and the way forward. Trends Ecol Evol. 2013;28:58–66.

- Erdman DS. Exotic fishes in Puerto Rico. In WR Courtenay, JR Stauffer ed. Distribution, biology, and management of exotic fishes. Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press; 1984. p. 162–176.

- Erdman DS. Inland game fishes of Puerto Rico. 2d ed. Federal Aid Proj. F–1–20. San Juan, PR: US Department of Agriculture, Centralized and Ancillary Services.

- Neal JW, Lilyestrom CG, Kwak TJ. Factors influencing tropical island freshwater fishes: species, status, and management implications in Puerto Rico. Fisheries. 2009;34(11):546–554.

- Bunkley-Williams L, Williams EH, Lileystrom CG, et al. The South American sailfin armored catfish, Liposarcus multiradiatus (Hancock), a new exotic established in Puerto Rican fresh waters. Caribbean J Sci. 1994;30(1–2):90–94.

- Erdman DS. Notes on the biology of the gobiid fish Sicydium plumieri in Puerto Rico. Bull Mar Sci. 1961;11(1):448–456.

- Stoner AW. Community structure of the demersal fish species of Laguna Joyuda, Puerto Rico. Estuaries Coasts. 1986;9(2):142–152.

- Engman AC, Hogue GM, Starnes WC, et al. Puerto Rico Sicydium goby diversity: species-specific insights on population structures and distributions. Neotropical Biodivers. 2019;5(1):22–29.

- Ramírez A, De Jesús-Crespo R, Martinó-Cardona DM, et al. Urban streams in Puerto Rico: what can we learn from the tropics? J North Am Benthological Soc. 2009;28(4):1070–1079.

- Rodríguez-Barreras R, Zapata-Arroyo C. The first record of the African catfish Clarias gariepinus (Burchell, 1822) in Puerto Rico. Int J Aquat Sci. 2019;10(2):1–2.

- United States Census Bureau. US Department of Commerce. c2020. [Updated 2019 Jul 1; cited 2020 Feb 02]. Available from: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/PR#

- Ewel JJ, Whitmore JL. The ecological life zones of Puerto Rico and the US Virgin Islands. USDA Forest Service, Institute of Tropical Forestry, Research Paper, ITF-018, 18. 1973.

- Calvesbert RJ. Climate of Puerto Rico and the US Virgin Islands. Climatography of the United States 60-52. Silver Spring, MD: US Department of Commerce. Environmental Science Administration, Environmental Data Service; 1970.

- Ahmad R, Scatena FN, Gupta A. Morphology and sedimentation in Caribbean montane streams: examples from Jamaica and Puerto Rico. Sediment Geol. 1993;85(1–4):157–169.

- Pike AS, Scatena FN, Wohl EE. Lithological and fluvial controls on the geomorphology of tropical montane stream channels in Puerto Rico. Earth Surf Process Landf. 2010;35(12):1402–1417.

- Falcón W, Tremblay RL. From the cage to the wild: introductions of Psittaciformes to Puerto Rico. Peer J. 2018;6:e5669.

- WoRMS. Editorial Board (2019). World register of marine species. [cited 2019 Nov 19]. Available from: http://www.marinespecies.org

- Evermann BW, Marsh MC. The fishes of Porto Rico. Bul US Fish Comm. 1902;20(1):49–350.

- Danforth ST. An ecological study of Cartagena Lagoon, Porto Rico, with special references to birds. Journ Deprt Agri Porto Rico. 1926;10(1):1–136.

- Hildebrand SF. An annotated list of fishes of the fresh waters of Puerto Rico. Copeia. 1935;2:49–56.

- Page LM, Burr BM. A field guide to freshwater fishes of North America north of Mexico. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company; 1991. p. 432.

- Ortega H, Vari RP. Annotated checklist of the freshwater fishes of Peru. Smithson Contrib Zool. 1956;437:1–25.

- Kwak TJ, Engman AC, Fisher JR, et al. Drivers of Caribbean Freshwater Ecosystems and Fisheries. In: Taylor WW, Bartley DM, Goddard CI, et al.editors. Freshwater, fish and the future: proceedings of the global cross-sectoral conference. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome; Michigan State University, East Lansing; and American Fisheries Society. Maryland: Bethesda; 2016. p. 219–232.

- Kottelat M, Whitten AJ, Kartikasari SN, et al. Freshwater fishes of Western Indonesia and Sulawesi. Hong Kong: Periplus Editions; 1993.

- Pethiyagoda R, Meegaskumbura M, Maduwage K. A synopsis of the South Asian fishes referred to Puntius (Pisces: cyprinidae). Ichthyol Explor Freshwaters. 2012;23(1):69–95.

- Rainboth WJ. Fishes of the Cambodian Mekong. FAO species identification field guide for fishery purposes. Ichthyological research: FAO, Rome; 1996. p. 265.

- Rodriguez CM. Phylogenetic analysis of the tribe Poeciliini (Cyprinodontiformes: poeciliidae). Copeia. 1997;4:663–679.

- Nichols JT. The fishes of Porto Rico and the Virgin Islands. Scientific survey of Porto Rico and the Virgin Islands. N Y Acad Sci. 1929;10(2):161–295.

- Nichols JT. The fishes of Porto Rico and the Virgin Islands. Scientific survey of Porto Rico and the Virgin Islands. N Y Acad Sci. 1930;10(3):299–399.

- Kenny JS. Views from the bridge: a memoir on the freshwater fishes of Trinidad. Maracas, St. Joseph: Trinidad and Tobago; 1995. Julian S. Kenny; p. 1–98.

- Wischnath L. Atlas of livebearers of the world. United States of America: TFH Publications Inc.; 1993. p. 336.

- Harrison IJ, Mugilidae L, Fischer W, Krupp F, Schneider W, et al., editors Guía FAO para Identificación de Especies para los Fines de la Pesca. Pacifico Centro-Oriental. Vol. 3. Rome: FAO; 1995. p. 1293–1298.

- Baker WH, Blanton RE, Johnston CE. Diversity within the Redeye Bass, Micropterus coosae (Perciformes: centrarchidae) species group, with descriptions of four new species. Zootaxa. 2013;3635(4):379–401.

- Lee DS, Gilbert CR, Hocutt CH, et al. Atlas of North American freshwater fishes. North Carolina: North Carolina State Museum of Natural History; 1980. http://www.nativefishlab.net/library/textpdf/20231.pdf

- Bagley JC, Matamoros WA, McMahan CD, et al. Phylogeography and species delimitation in convict cichlids (Cichlidae: amatitlania): implications for taxonomy and Plio-Pleistocene evolutionary history in Central America. Biol J Linn Soc. 2016;120(1):155–170.

- Schmitter-Soto JJ. A systematic revision of the genus Archocentrus (Perciformes: cichlidae), with the description of two new genera and six new species. Zootaxa. 2007;1603:1–78.

- Kullander SO, Hartel KE. The systematic status of cichlid genera described by Louis Agassiz in 1859: amphilophus, Baiodon, Hypsophrys and Parachromis (Teleostei: cichlidae). Ichthyol Explor Freshwat. 1997;7(3):193–202.

- Lee DS, Platania SP, Burgess GH. Atlas of North American freshwater fishes - 1983 supplement. In: North Carolina Biological Survey and the North Carolina State Museum of Natural History. Raleigh, NC; 1983;854.

- Lopez HL, Menni RC, Miguelarena AM. Lista de los peces de agua dulce de la Argentina. Biologia Acuatica. 1987;12:1–50.

- Kullander SO, Nijssen H. The cichlids of Surinam: teleostei, Labroidei. The Netherlands: Leiden; 1989.

- Kullander SO. Cichlidae (Cichlids). In: Reis RE, Kullander SO, Ferraris CJ, editors. Checklist of the Freshwater Fishes of South and Central America. Vol. 2003. Porto Alegre, Brasil: Edipucrs; 2003. p. 605–654.

- Trewavas E. Tilapiine fishes of the genera Sarotherodon, Oreochromis and Danakilia. Vol. 1983. London (UK): British Mus. Nat. Hist.; 1983. p. 1–583 p.

- Conkel D. Cichlids of North and Central America. USA. New Jersey: TFH. Publications Inc.; 1993.

- AR D, UK S. Molecular phylogeny and revised classification of the haplotilapiine cichlid fishes formerly referred to as “Tilapia”. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2013;68(1):64–80.

- Robins CR, Ray GC. A field guide to Atlantic coast fishes of North America. Boston, Houghton: Mifflin Company; 1986. p. 354.

- Bacheler NM, Neal JW, Noble RL. Diet overlap between native bigmouth sleepers (Gobiomorus dormitor) and introduced predatory fishes in a Puerto Rico reservoir. Ecol Freshwater Fish. 2004;13:111–118.

- Claro R, Parenti LR. The marine ichthyofauna of Cuba. In: Claro R, Lindeman KC, Parenti LR, editors. Ecology of the marine fishes of Cuba. Washington and London: Smithsonian Institution Press; 2001. p. 21–57.

- Watson RE. Sicydium from the Dominican Republic with Description of a New Species (Teleostei: gobiidae). Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde. 2000;608:1–31.

- Teugels GG. A systematic revision of the African species of the genus Clarias (Pisces; Clariidae). Ann Mus R Afr Centr, Sci Zool. 1986;247:1–199.

- Hardman M, Page LM. Phylogenetic relationships among bullhead catfishes of the genus Ameiurus (Siluriformes: ictaluridae). Copeia. 2003;1:20–33.

- Burgess WE. An atlas of freshwater and marine catfishes. A preliminary survey of the Siluriformes. New Jersey: TFH Publications, Inc.; 1989.

- Roberts TR, Vidthayanon C. Systematic revision of the Asian catfish family Pangasiidae, with biological observations and descriptions of three new species. Proc Acad Nat Sci Philad. 1991;143:97–144.

- Naylor R, Williams SL, Strong DR. Aquaculture - a gateway for exotic species. Science. 2001;294:1655–1656.

- Garcia‐Pérez A, Alston DE, Cortés‐Maldonado R. Growth, survival, yield, and size distributions of freshwater prawn Macrobrachium rosenbergii and tilapia Oreochromis niloticus in polyculture and monoculture systems in Puerto Rico. J World Aquacult Soc. 2000;31(3):446–451.

- Tveteras S, Asche F. International fish trade and exchange rates: an application to the trade with salmon and fishmeal. Appl Econ. 2008;40(13):1745–1755.

- Gertzen E, Familiar O, Leung B. Quantifying invasion pathways: fish introductions from the aquarium trade. Can J Fisheries Aquat Sci. 2008;65(7):1265–1273.

- Moyle PB, Li HW, Barton BA. The Frankenstein Effect: impact of Introduced Fishes on Native Fishes in North America. In: RH Shroud editor. The role of fish culture in fisheries management. Bethesda (MD): American Fisheries Society. 1987. p. 415–426.

- Bruton MN. Have fishes had their chips? The dilemma of threatened fishes. Environ Biol Fish. 1995;43(1):1–27.

- Coad BW, Abdoli A. Exotic fish species in the fresh waters of Iran. Zool Middle East. 1993;9(1):65–80.

- Reglamento de Pesca de Puerto Rico. DRNA publication; no. #7949; 2010. p. 1–99.

- Olmeda ML, Lilyestrom C, Del Moral R, et al. Population Dynamics of Introduced Sunfish Species to Tropical Reservoirs. Poster presented at: American Fisheries Society 144th Annual Meeting; 2014 Aug 17- 2;Québec City, Canada.

- Olmeda ML, Del Moral R, Lilyestrom C Puerto Rico Department of Natural and Environmental Resources. Federal Aid in Sport Fish Restoration Project F-52.1. Freshwater Sport Fish Community Assessments in Puerto Rico Reservoirs and Lagoons. San Juan, Puerto Rico: DENR publication; no. F-52.1; 2007.