ABSTRACT

We describe for the first time the immature stages of the Ecuadorian endemic urban butterfly, Catasticta flisa duna Eitschberger & Racheli, from Quito, Ecuador. A mistletoe species, Phoradendron nervosum Oliv. (Viscaceae), is identified as the host plant. Phoradendron nervosum is an aerial-stem hemiparasite in the order Santalales that is parasitic on Prunus serotina (Ehrh), a common tree species in the gardens and parks of Quito. We report Podisus sp. (Pentatomidae), a predatory stink bug, as a predator of C. f. duna pupa. Additionally, parasitoid flies (Tachinidae) were obtained from some larvae. We compare the immature stages of C. f. duna and the subspecies C. flisa flisandra Reissinger from Costa Rica, providing for the first-time head chaetotaxy and setal maps for this diverse genus. Finally, we emphasize the importance of urban green spaces which provide habitat for many native species. Such urban oases should be considered as important resources for conservation, whose development and management benefit urban biodiversity and ecological networks, as well as enhancing the quality of life for the city’s human inhabitants.

RESUMEN

Describimos por primera vez los estados inmaduros de la mariposa endémica ecuatoriana Catasticta flisa duna de Quito Ecuador. Un muérdago, Phoradendron nervosum Oliv. (Viscaceae), se identifica como la planta hospedera, esta es un hemiparásito aéreo en el orden de los Santalales, el cual es un parásita a Prunus serotina Ehrh. que es común encontrar en los jardines y parques de Quito. Se reporta a un chinche Podisus sp. (Pentatomidae) como depredador, encontrándole alimentándose de pupas y se obtienen moscas parasitoides (Tachinidae) de algunas larvas. Comparamos entre los estados inmaduros de C. f. duna y C. flisa flisandra de Costa Rica, proveemos por primera vez dibujos de la quetotaxia de la cabeza y mapas setales para este género diverso. Finalmente, enfatizamos la importancia de las áreas verdes en las ciudades, las cuales brindan oportunidades de hábitat para especies nativas. Estos oasis urbanos denberian ser considerados como recursos importantes para la conservacio, estrategias podrían proporcionar beneficios para otros elementos de la fauna urbana, las redes ecológicas y para mejorar la calidad de vida de las personas.

PALABRAS CLAVE:

Introduction

The genus Catasticta (Butler, 1870) is one of the most species-rich Andean butterfly radiations, with 97 described species [Citation1,Citation2]. It is distributed from Mexico to northern Bolivia, with its center of diversity in the middle elevation cloud forests of the tropical eastern Andes. Although the genus has been the subject of some research in the last few years [Citation3–7], and several new species have been described [Citation2,Citation8], there is still little known about the biology of most species. Of the currently described 97 species, we have some information about the immature stages and host plant associations for fewer than 10 species [Citation9–14]; life history information has been documented for seven of those species only from Central America [Citation11].

Schultze-Rhonhof [Citation9] was the first to describe the immature stages of a Catasticta species. For Catasticta flisa, he briefly noted the pupa, the habitat and the host plant (Loranthaceae) where the pupa was found at “Rio Ambato”, Tungurahua, Ecuador. Assuming the locality information is broadly correct, his notes should apply to the subspecies C. f. dilutior (Avinoff, 1926.) Many years later, Bollino and Rodriguez [Citation10] provided photographs of the pupa of another subspecies of C. flisa, C. f. flisoides (Eitschberger & T. Racheli, 1998), from Colombia. Braby and Nishida [Citation11] provided the most comprehensive descriptions to date of Catasticta immature stages and host plants, contributing life history information for seven species. They reported the following host plants: Dendrophthora costaricensis Urb. (for C. cerberus Godman and Salvin, 1889), Phoradendron velutinum (DC.) Oliv. and Dendrophthora costaricensis Urb. (for C. teutila flavomaculata Lathy & Rosenberg, 1912), Antidaphne viscoidea (for C. sisamnus sisamnus (Fabricius, 1793), C. hegemon hegemon Godman & Salvin, 1889, C. ctemene actinotis Butler, 1872, and C. theresa Butler and H. Druce, 1874), and Phoradendron undulatum (for C. flisa flisandra Reissinger, 1972), all of them in the families Loranthaceae, Santalaceae and Viscaceae. This information was obtained from individuals reared in Costa Rica and Panama and from material examined in museums in Mexico. Subsequently, Montero and Ortíz [Citation12] described the immature stages of a high elevation species, C. semiramis semiramis (Lucas, 1850), from Colombia, identifying the host plant as Gaiadendron punctatum (Ruiz & Pavon) (Loranthaceae). Additional information about the immature stages and host plant associations of the genus is mostly not clear or reliable, and therefore needs confirmation in future studies, as several records likely represent the tree on which the host plant mistletoe was growing, and not the actual host plant [Citation13]. Nevertheless, Callaghan (2019) recently documented the immature stages of Catasticta philothea (Felder & Felder, 1865) in Colombia remarkably feeding not on a mistletoe, as with every other known species of Catasticta (and related genera), but feeding on a tree of the family Melastomataceae, underlining how much remains unknown about the biology of Catasticta. In terms of the behavior of the immature stages, little has been documented, but larvae and pupae are highly gregarious and some species feed at night, especially in the last instar [Citation11]. More information on the biology of this highly diverse genus could certainly help illuminate the factors that have promoted its radiation, such as the role of host plant shifts in Catasticta diversification [Citation5,Citation11,Citation15].

Catasticta flisa (Herrich-Schaffer, [1858]), Narrow-banded Dartwhite, is one of the more widespread species in the genus, ranging from Mexico to Ecuador. Currently, there are 13 recognized subspecies [16,1,3,]: C. f. flisa (Herrich-Schäffer, [1858]) (Mexico to Guatemala); C. f. archoflisa Eitschberger & T. Racheli, 1998 (Panama); C. f. arechiza (Reakirt, 1866) (Mexico); C.f. briseis Eitschberger & T. Racheli, 1998 (Panama); C. f. dilutior Avinoff, 1926 (Colombia and Ecuador); C. f. duna Eitschberger & T. Racheli, 1998 (Ecuador); C. f. flisandra Reissinger, 1972 (Mexico to Costa Rica); C. f. flisella Reissinger, 1972 (Mexico to Panama); C. f. flisoides Eitschberger & T. Racheli, 1998 (Colombia); C. f. melanisa Eitschberger & T. Racheli, 1998 (Costa Rica); C. f. noakesi Joicey & Rosenberg, 1915 (Colombia); and C. f. postaurea F. Brown, 1933 (Colombia).

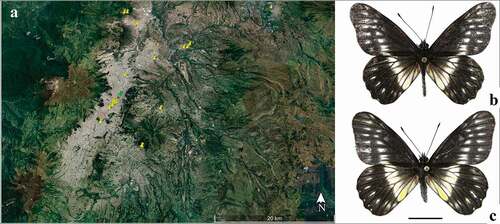

Eitschberger and Racheli [Citation16] described the subspecies C. f. duna () from Quito, Ecuador, and to date this taxon is still known only from that city and the surrounding dry inter-Andean valleys of Pichincha and Imbabura provinces, where it is largely restricted to the city of Quito and surrounding areas of Guayllabamba, Tingo, Tumbaco, Mitad del Mundo, Cayambe, Calderón La Kennedy and Volcán Pululahua ().

Figure 1. (a) Map showing records of C. f. duna in Quito and surrounding areas, and the locality where immature stages were found (Parque la Carolina, green pin); (b) male dorsal view; (c) female dorsal view

Figure 2. Immature stages. (a) Cluster of eggs on a leaf; (b) Eggs, dorsal view; (c) Group of newly emerged larvae; (d) First instar dorsal and lateral view; (e) Second instar dorsal and lateral view; (f). Third instar dorsal and lateral view; (g). Fourth instar dorsal and lateral view; (h) Fifth instar dorsal and lateral view; (i). Pupa lateral view; (j) Pupa dorsal view

Catasticta f. duna is frequently encountered flying within highly urbanized areas of Quito, visiting flowers, mating and even puddling in fountains (pers. obs.) (). It is an easily identifiable taxon, and according to Eitschberger & T. Racheli [Citation16] it is “characterised by the submarginal spots of both wings transformed in thin streaks, and the submarginal spots of the wings long and directed outwards. FWs upperside discal band reduced for the strong suffusion of black scales on the white spots. Premarginal spots elongated in whitish streaks. HWs. upperside: The discal band is also reduced in size and the premaginal spots elongated. On the underside of the HWs the white premarginal spots are elongated and confluent with the marginal yellow wedges. The females have same pattern of the males”.

Interestingly, this subspecies lives at unusually high elevations (2500–2800 m) in comparison with other subspecies of C. flisa (800–2400 m).

The peculiar distribution and rather different apparent habitat requirements of this taxon, in comparison with the more widespread taxa that inhabit wet cloud forest on the outer east and west Andean slopes in Ecuador, are therefore intriguing.

The main purpose of this paper is, therefore, to contribute to basic knowledge of Catasticta biology, by describing for the first time the immature stages of C. flisa duna. We here present information about the larval morphology, host plant, natural enemies, and notes on the general biology of C. f. duna, which may help to understand the peculiar distribution and unusual habitats occupied by this taxon.

Materials and methods

Study area

Eggs, larvae and pupae of C. f. duna were collected in a 62-hectare urban recreational park, Parque la Carolina, in the city of Quito (−0.185543 − 78.482836) at 2775 m (). The climate in Quito during the time when larvae were found is characterized by usually sunny mornings and cloudy afternoons, often with showers, and average daily temperatures of 15° [Citation17]. Immature stages were found by searching mistletoes at the border of Parque la Carolina and in the central median of an adjacent, busy street, Avenida de los Shyris, where adults were observed flying. Immature stages were collected and reared in individual containers. Each day, feces and old leaves were removed from the containers and fresh leaves of the host plant were supplied. Photographs were taken of the individual stages and morphological data were recorded.

Morphology

For description of the larval chaetotaxy and general morphology of immature stages, we followed the terminology of Stehr [Citation18]. Photos were taken using a Canon 5D Mark III DSLR camera with Canon MP-E 65 mm f/2.8 1–5x Macro Photo Lens. For morphological measurements, a Fowler Sylvac Euro-Cal “Mark III” Digital Caliper was used. Illustrations were made using the preserved specimens and images with the help of a Bamboo Wacom and Inkscape software.

Results

Description of immature stages

Egg (n = 94)

Eggs were laid on the underside of leaves in clusters of 46–48 (n = 3). Eggs white when first laid and turning yellow before hatching, barrel-shaped with longitudinal ribs on sides. Duration from oviposition to hatching was 13–14 days ().

First instar larva (n = 48)

Head capsule length: 0.79 mm ± 0.02 mm, width: 0.64 mm ± 0.03 mm; length of body from head to A10: 5.77 mm ± 0.06 mm. Head black, with colorless primary setae arising from colorless chalazae, body yellow after hatching, changing to greenish-brown after consuming food, with a reddish-brown mid-dorsal line. Body with a pair of black dorsal setae and fine colorless primary setae arising from white and pale yellow chalazae that form intercalated colored stripes. Prothorax with a dark reddish-brown dorsal plate. After hatching, larvae first feed on chorion and then consume the surface of leaves. Larvae feed gregariously and produce some silk, when disturbed larvae move their heads in a sudden movement backwards. Duration 10–11 days ().

Second instar larva (n = 38)

Head capsule length: 1.36 mm ± 0.03 mm; width: 1.17 mm ± 0.02 mm; length of body from head to A10: 8.83 mm ± 0.11 mm. Similar to first instar, but body reddish-brown with more marked white and yellow chalazae from which arise colorless setae. Darker mid-dorsal line. Prothorax with a rectangular dark reddish-brown dorsal plate. Duration 10–11 days ().

Third instar larva (n = 25)

Head capsule length: 1.97 mm ± 0.04 mm; width: 1.89 mm ± 0.05 mm; length of body from head to A10: 17.71 mm ± 0.23 mm. Head with colorless setae arising from orange chalazae; body with yellow stripes, with wider yellow chalazae. Prothorax with a triangular black dorsal plate, with yellow spots on sides. Duration 8–10 days ().

Fourth instar larva (n = 25)

Head capsule length: 2.80 mm ± 0.04 mm; width: 2.50 mm ± 0.05 mm; length of body from head to A10: 21.34 mm ± 0.35 mm. Similar to third instar, but mid-dorsal line darker, almost black; head with more conspicuous orange chalazae from which arise colorless setae. Duration 10–12 days ().

Fifth instar larva (n = 18)

Head capsule length: 3.73 mm ± 0.04 mm; width: 3.21 mm ± 0.03 mm; length of body from head to A10: 21.9 mm ± 0.033 mm. Similar to fourth instar, but yellow stripes with yellow chalazae wider, almost covering the whole body, giving larvae a greenish-yellow color. Before pupation, larvae descend from host plant to bark and leaves of host tree where they pupate. Several were also found hanging from host plant to ground on a silk thread. Duration 7–11 days ().

Pupa (n = 40)

Pupa length: 22.4 mm ± 0.12 mm (excluding anterior projection); width: 6 mm ± 0.09 mm. Pupa pale green, with a few large black spots; head with a prominent yellow anterior projection, oriented upwards and bifurcated at apex and two smaller black projections posteriorly. Both prothorax and mesothorax have a longitudinal dorsal ridge, but at mesothorax, it is orange and more prominent. Abdominal segments A2 to A4 have long spine-like black dorsolateral projections with yellow at base; A2 to A8 have in each segment a spine-like black mid-dorsal projection (A2 and A8 present mid-dorsal projections smaller than remaining segments) (). When agitated, pupae move abdominal segments in what may be defensive behaviour.

Host plant and ecological interactions

Larvae and pupae were found by PSP at noon on 26 April 2019, at the border of Parque La Carolina and in an adjacent median area of the busy Avenida de los Shyris (), on a large group of mistletoes parasitizing a medium-sized tree of Prunus serotina (Ehrh. 1783) (Rosaceae). The host plant was identified as Phoradendron nervosum (Oliv. 1865) (Viscaceae), an aerial-stem hemiparasite in the order Santalales which is a common parasite of P. serotina [Citation19], a tree that is common in the gardens and parks of Quito.

Biology

Adults of C. f. duna are commonly observed flying in Quito, during sunny periods in the morning and early afternoon. They also are frequently seen feeding on flowers of Taraxacum officinale (G. H. Weber ex Wigg) (Asteraceae), mating (), and a male was observed puddling at a fountain in Plaza Foch (pers. obs.). Adults have been observed in a number of months throughout the year (February, April, May, June, August, September and November) (pers. obs.), which could indicate that the subspecies is multivoltine with several generations per year. Adults took between 2 and 3 hours after emergence before their wings were hardened and ready for flight.

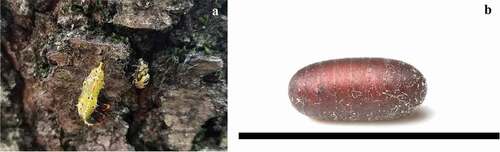

Natural enemies and parasites

Several immature individuals of Podisus sp. (Hemiptera, Pentatomidae), a predatory stink bug, were found actively feeding on several pupae (). This represents the first report of this bug predating Catasticta, although it has been recorded previously as a predator of other Lepidoptera immature stages, even being used in biological control of pest insects [Citation20–22]. Additionally, five tachind fly larvae emerged from individual last instar larvae and pupated.

Discussion

Catasticta is a highly diverse genus of Neotropical butterflies, with only fragmentary information available for the immature stages. Here, we provide detailed information on the morphology, larval host plant and general biology of the immature stages of C. f. duna, and head chaetotaxy and setal maps are provided for the first time for the genus. Catasticta flisa duna and C. f. flisandra have very similar immature stages, but the first taxon has orange chalazae with white setae on the head from the third instar, whereas C. f. flisandra has these orange chalazae only in the fifth instar [Citation11]. In the pupal stage, there are more marked differences: on the abdominal segments, C. f. flisandra has long spine-like orange-red dorso-lateral and mid-dorsal projections with green at the base [Citation11], whereas in C. flisa duna the same spine-like projections are black at the tip and yellow at the base.

The host plant was identified as Phoradendron nervosum (Oliv. 1865) (Viscaceae), which is a common parasite of P. serotine [Citation19], but which has also been reported to infest other tree genera such as Acacia Martius, 1829, and Casuarina Linnaeus, 1759, which are also present in the Quito area [Citation23]. The mistletoe ranges from Mexico to tropical South America, and can be found at elevations between 50 and 3000 m in the Andes [Citation19]. The foliage is dichotomously branching with long leaves and abundant yellow inflorescences and fruits [Citation24]. The genus Phoradendron is considered the most diverse of the mistletoes in the Americas and currently includes approximately 234 described species, mostly distributed in mountainous regions [Citation19] (). Interestingly, although the parasitized tree P. serotina is widely distributed in the Ecuadorian highlands, that species is not native to Ecuador; P. serotina is native to North America and was introduced in Ecuador [Citation25], while P. nervosum is native to Central America and South America [Citation19]. Therefore, the relationship between the parasite and host has recently become established, perhaps favoring the maintenance of C. f. duna in urban areas of Quito. A number of other species also make use of P. nervosum in the locality where the immature stages were found. For example, two bird species, Golden-rumped Euphonia Euphonia cyanocephala Vieillot, 1818, and Great Thrush Turdus fuscater (Lafresnaye & d´Orbigny, 1837), were seen feeding on the fruits of the mistletoe, and we assume may help disperse the seeds through their feces, which were observed attached to branches via an apparently sticky thread (pers. obs.).

Immatures of Podisus sp., a predatory bug, were recorded for the first time feeding on a pupa, and five parasitoid Tachinidae flies were obtained from larvae. Braby and Nishida [Citation11] previously reported the presence of parasitoids in Catasticta, including Tachinidae and Ceratopogonidae flies, and wasps of the families Eurytomidae and Chalcididae. Tachinidae flies are known parasitoids of Pieridae in general [Citation26,Citation27] and of Catasticta sisamnus in particular [Citation11].

Recent studies have shown that urban green areas provide important habitat opportunities for butterflies [Citation28–31], and other pollinators, and should be incorporated into conservation strategies [Citation30]. Municipal decision-makers and planners could use published information on the biology of species inhabiting urban areas to enhance green spaces for both biodiversity and the public [Citation31]. For example, planting the host tree P. serotina in parks and boulevards in Quito could play a significant role in conserving the host plant mistletoe P. nervosum, provide a food supply for birds, and presumably benefit the urban populations of the endemic butterfly C. f. duna. Management of green spaces could potentially provide benefits for other elements of the urban fauna and flora, strengthen ecological networks and facilitate encounters with nature among the people that live in cities [Citation32,Citation33].

Finally, the discovery of the immature stages of the C. f. duna in the middle of the city of Quito demonstrates that urban settings are being actively used by some fauna, in this case, an endemic butterfly subspecies, which have adapted to disturbed and non-natural habitats. This discovery also highlights the need to look more carefully to understand the organisms that are literally a few steps from where we live; we only can imagine how little we know of the other fauna and flora that is not so close to home.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Lamas G. Atlas of neotropical Lepidoptera; checklist: part 4A; hesperioidea-papilionoidea. Gainesville, FL: Association for Tropical Lepidoptera; Scientific Publishers; 2004.

- Nakahara S, Macdonald JR, Delgado J, et al. Discovery of a rare and striking new pierid butterfly from Panama (Lepidoptera: pieridae). Zootaxa. 2018;4527(2):281–291.

- Bollino M, Costa M. An illustrated annotated check-list of the species of Catasticta (s.l.) Butler (Lepidoptera: pieridae) of Venezuela. Zootaxa. 2007;1469(1):1–42.

- Bollino M, Boyer P. Revisional notes on the “cinerea” group of Catasticta Butler, 1870. (Lepidoptera: pieridae). Genus. 2008;19(3):361–370.

- Padron PS Molecular phylogeny and biogeography of the genus Catasticta Butler, 1870 [dissertation]. Gainesville, (FL); University of Florida; 2014.

- Bollino M, Padrón PS. Description of a new subspecies of Catasticta fulva Joicey & Rosenberg, 1915, with notes on several other species in the genus (Lepidoptera: pieridae). Trop Lepid Res. 2016;26(1):1–5.

- Dufour PC, Willmott KR, Padrón PS, et al. Divergent melanism strategies in Andean butterfly communities structure diversity patterns and climate responses. J Biogeogr. 2018;45(11):2471–2482.

- Bollino M. Two new species of Catasticta Butler, 1870 from Peru (Lepidoptera: pieridae). Genus. 2018;19(3):355–360.

- Schultze-Rhonhof A. Ueber die ersten Stände von Catasticta flisa H. SCHÄFF. Dt Ent Z Iris. 1935;49:52–54.

- Bollino M, Rodriguez G. Mariposas de Colombia. Vol. 2. Pieridae, Bogota Colombia: CARLEC Ltda; 2004.

- Braby MF, Nishida K. The immature stages, larval food plants and biology of Neotropical mistletoe butterflies (Lepidoptera: pieridae). II. The Catasticta group (Pierini: aporiina). J Nat Hist. 2010;44(29–30):1831–1928.

- Montero F, Ortiz M. Aporte al conocimiento para la conservación de las mariposas (Hesperioidea y Papilionoidea) en el Páramo del Tablazo, Cundinamarca (Colombia). Bol Cient Mus His Nat. 2013;17(2):197–227.

- Beccaloni GW, Viloria AL, Hall SK, Robinson GS. Catalogue of the Hostplants of the Neotropical Butterflies]. m3m- Monografias Tercer Milenio. Vol. 7. Zaragoza (Spain): sociedad Entomologica Aragonesa (SEA); Red Iberoamericana de Biogeografia y Entomologia Sistematica (RIBES); Ciencia y Tecnologia para el Desarrollo (CYTED); Natural History Museum. London, UK (NHM): Instituto Venezolano de Investigaciones Cientificas, Venezuela (IVIC); 2008.

- Callaghan, CJ. Notes on the biology of a nonconformist Catasticta species from Colombia: catasticta philothea (Lepidoptera: pieridae). J Lepid Soc. 2019;73(3):203–207.

- Braby MF, Trueman JWH. Evolution of larval host plant associations and adaptive radiation in pierid butterflies. J Evol Biol. 2006;19(5):1677–1690.

- Eitschberger U, Racheli T. Catasticta studies (Lepidoptera: pieridae). Neue Ent Nachr. 1998;41:5–93.

- INAMIH [Internet]. Quito; [cited 2019 July 15]. Available from: http://www.serviciometeorologico.gob.ec

- Stehr FW. Immature insects: volume 1. Dubuque, USA: Kendall Hunt Publishing; 1987.

- Kuijt J. Monograph of Phoradendron (Viscaceae). Syst Bot Monogr. 2003;66:1–643.

- Torres JB, Zanuncio JC, Moura MA. The predatory stinkbug Podisus nigrispinus: biology, ecology and augmentative releases for lepidopteran larval control in Eucalyptus in Brazil. Biocontrol News Inf. 2006;27(15):1–18.

- Zanuncio JC, Domingues da Silva CA, Rodrigues de Lima E, et al, Predation rate of Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: noctuidae) larvae with and without defense by Podisus nigrispinus (Heteroptera: pentatomidae). Braz Arch Biol Technol. 2008;51(1):121–125.

- Nájera-Miramontes D, Ordóñez-García M, Ríos-Velasco C, et al. Depredación por Podisus maculiventris (Say) sobre larvas de Choristoneura rosaceana (Harris). Acta Zool Mex. 2016;32(2):147–152.

- Padilla I, Asanza M. Arboles y arbustos de Quito. Quito, Ecuador: Herbario Nacional del Ecuador; 2001.

- Suaza‐Gaviria V, González F, Pabón‐Mora N. Comparative inflorescence development in selected Andean Santalales. Am J Bot. 2017;104(1):24–38.

- Fresnedo-Ramirez J, Segura S, Muratalla- Lua A. Morphovariability of capulin (Prunus serotina Ehrh.) in the central-western region of Mexico from a plant genetic resources perspective. Genet Resour Crop Evol. 2011;58:481–495.

- Hudon M. Phryxe vulgaris (Fall.) (Diptera: tachinidae), a new parasite of Pieris rapae (L.) (Lepidoptera: pieridae) in Canada. Can Entomol. 1957;89(12):546.

- Cave RD, Cordero RJ. Parasitoides de Leptophobia aripa Boisduval (Lepidoptera: pieridae) en repollo y brócoli en Honduras. Ceiba. 2015;40(1):51–55.

- Tam KC, Bonebrake TC. Butterfly diversity, habitat and vegetation usage in Hong Kong urban parks. Urban Ecosyst. 2016;19(2):721–733.

- Ramírez-Restrepo L, MacGregor-Fors I. Butterflies in the city: a review of diurnal Lepidoptera. Urban Ecosyst. 2017;20(1):171–182.

- Johnston MK, Hasle EM, Klinger KR, et al. Estimating milkweed abundance in metropolitan areas under existing and user-defined scenarios. Front Ecol Evol. 2019;7:1–22.

- Lewis AD, Bouman MJ, Winter A, et al. Does nature need cities? Pollinators reveal a role for cities in wildlife conservation. Front Ecol Evol. 2019;7:1–8.

- Basset Y, Lamarre GP. Toward a world that values insects. Science. 2019;364(6447):1230–1231.

- Habel JC, Samways MJ, Schmitt T. Mitigating the precipitous decline of terrestrial European insects: requirements for a new strategy. Biodivers Conserv. 2019;28(6):1343–1360.