ABSTRACT

The nest structure of two species of small mammals, Marmosa simonsi and Rhipidomys latimanus were recorded for the first time. Nests were found inside artificial nest boxes in a tropical dry forest remnant ecosystem in Western Ecuador. We described the nests and categorized them as rearing nest, permanent resting nest and transient refuge, depending on their intended use. Artificial nest boxes provide an optimal place for pup rearing and resting for these small mammals. These nest sites can be useful for ecological studies of behavior and habits of elusive, poorly-known mammalian species.

Graphical abstract

RESUMEN

Se presentan por primera vez observaciones de la estructura del nido de dos especies de mamíferos pequeños, Marmosa simonsi y Rhipidomys latimanus. Los nidos fueron encontrados dentro de cajas nidos artificiales instaladas en un remanente de bosque seco tropical en Ecuador occidental. Describimos los nidos y los categorizamos como nido de crianza, nido de descanso permanente y refugio transitorio, de acuerdo al uso por parte de M. simonsi. Las cajas nidos artificiales proveen un lugar óptimo para la crianza, y un lugar de descanso atractivo para estos mamíferos pequeños. Estos sitios de anidación pueden ser útiles en estudios ecológicos, que incluyan determinar los hábitos y comportamientos de mamíferos pequeños, en especial especies poco conocidos y elusivas como las de hábito arborícola.

The practice of using artificial boxes as an alternative to study vertebrates in situ [Citation1] is an ideal method to study behavior and provides the opportunity to record species that very rarely fall into widely-used traps, such as small, arboreal mammals [Citation2,Citation3]. For example, some marsupial species build their nests inside of artificial boxes using plant materials [Citation4,Citation5], and several species of Marmosa (Didelphidae) have been found inside nest boxes set up for ornithological studies [Citation6,Citation7]. However, to our knowledge, there is no description of the behavior of species of Marmosa inside nest boxes, and particularly, how they build their nests. Our objective was to describe the behavior and nest structure of small mammals, opportunistically surveyed, inside artificial bird nest boxes set up on a tropical dry forest ecosystem.

The observations were conducted at Bosque Protector Cerro Blanco (–2.183056°, 80.015833°), a coastal tropical dry forest remnant located just outside of the city of Guayaquil on the southeast edge of the Chongón-Colonche mountains, Guayas Province, Western Ecuador. Tropical dry forests are dominated by at least 50% drought-tolerant deciduous trees, with a mean annual temperature above 25°C, annual precipitation ranges between 700–2000 mm, with three or more dry months per year [Citation8]. Cerro Blanco comprises around 2,000 ha of protected forest, adjacent to a limestone quarry mine and urbanized areas, therefore this reserve constitutes an Island of habitat for a number of endangered and endemic plant and animal species [Citation9]. One hundred and fifty nest boxes were set up by attaching wires and nails on trees at a height of 1.5 m, at elevations from 30 to 200 m asl, and separated at least 60 m from each other, adjacent to tourist trails and secondary roads. We monitored the artificial nest boxes twice weekly during daylight from 8:00 to 18:00, between January 2014 and June 2015. Each box had an entrance hole of 3.8 cm in diameter and a lateral opening for nest inspection [Citation10]. The nest boxes had an approximate volume of 5000 cm3, a height of 25.4 cm and a width of 16.5 cm, described in Bulgarella et al. [Citation11]. We recorded the presence of small mammals by direct observation, and indirectly by the presence of organic material (leaves) used for nest construction; species were identified using the Field Guide for Mammals of Ecuador [Citation12].

We found two mammal species, Marmosa simonsi Thomas 1899 (Dildelphimorphia, Didelphidae) and Rhipidomys latimanus (Tomes 1860) (Rodentia, Cricetidae) occupying the nest boxes. We recorded a percentage of nest box occupation of 13.3% (n = 20), by the two mammals, M. simonsi (n = 18;

Figure 1. Three nests categories according to the activity of Marmosa simonsi inside the nest box. A, B) Rearing nest, C, D) Permanent resting nest. Note the abandoned wasp nests inside the nest box, those did not seem to stop the opossum from using the box. E) Transient refuge. F) Examining a Rhipidomys latimanus found inside a nest box.

The leaves used in the construction of rearing and permanent resting nests were no longer than 5 cm, probably because it facilitates the transport to the nest boxes. The majority of leaves were identified as Guazuma ulmifolia (Malvaceae) and Cecropia spp. (Urticaceae) fragments, typical trees present in Ecuadorian dry forest, possibly the opossums choose leaves due to their small size and abundance in the surrounding area. Our observations coincide with the behavior of several Neotropical marsupials that use leaves to line their roosts [Citation13,Citation14], transporting the leaves using their tails. Thus, it is possible that M. simonsi might show this behavior.

We also observed, at two separate instances, nests built by the rodent Rhipidomys latimanus. This species built their nests using thin grass leaves. The leaves are loosely arranged inside the nest box, not compacted, making a small bed that covers a third of the nest box space, without a defined entrance or exit hole.

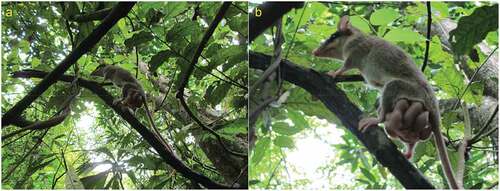

Both small mammals observed in our study are native to Western Ecuador. Simon’s Mouse Opossum (M. simonsi) inhabits Western Ecuador from 0 to 1900 m asl [Citation12,Citation15]. This species is closely related to M. robinsoni [Citation16] and little is known about its natural history [Citation17]. It is thought that they occupy abandoned bird nests or tree cavities [Citation18,Citation19], with no records on what materials they use to build their nests and how they use their nest space previous to this study. The use of the artificial nest boxes as a transient refuge coincides with the nomadic habit of other species of Marmosa in the wild that are known to use any available refuge at dawn [Citation20]. Thus, artificial nest provides a safe refuge during the day without the need to create a nest in trees or a burrow in the soil, which is energetically costly. Finally, observations of females with pups in the rearing nest coincide with previous observations of Marmosa spp. during the breeding season [Citation21,Citation22]. We observed one female opossum escape to the treetops with the pups in their pouch when we opened the nest box door ()

. Once we had ascertained that a nest box was occupied by an opossum, we stopped the weekly checks to avoid disturbance, thus, we had no cases of nest abandonment.Some M. simonsi individuals displayed an aggressive and threatening posture, hissing repeatedly when the nest box door was opened for examination (Suppl. Video 1). Other opossums had a calm and relaxed attitude to being found. These individuals did not seem worried about human presence/disturbance (, Suppl. Video 2).

Rhipidomys latimanus occupies all levels of the forest, but it spends most of its time in the canopy. Apparently, this species prefers mature or well-preserved forests and is considered a rare species to register [Citation23], possibly for its arboreal habits. We know little about its basic ecology [Citation24], and most knowledge is extrapolated from what it is known from other species in the genus Rhipidomys [Citation25]. We therefore present the first information on R. latimanus nests.

Although the number of occupied nest boxes in our study was low and similar to previous studies [Citation2,Citation5], the use of artificial nest boxes can prove helpful for observing behaviors displayed by elusive, arboreal, poorly-known mammal species [Citation17,Citation24,Citation26], especially if combined with camera trap techniques [Citation2,Citation13,Citation14,Citation27]. Our novel data describing how two small, non-volant mammals built their nests in a remnant tropical dry forest ecosystem in Western Ecuador, exemplifies the utility of artificial boxes for understanding reproductive and behavioral patterns with relatively low cost [Citation2,Citation28].

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (13.4 MB)Supplemental Material

Download Zip (125.3 MB)Acknowledgments

We thank Ing. Eric Horstman for permission to work in Bosque Protector Cerro Blanco. We also thank the Associate Editor and one anonymous reviewer for their useful comments that improved our original manuscript. The work has been partially funded by grants from the Institute on the Environment at the University of Minnesota and the International Community Foundation (Leona M. y Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust) to GEH. GABV thanks Grant Conicyt folio 21160182, Chile.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementry matrial

Supplemental data for this article can be accesed on the publisher’s website.

References

- Fokidis H, Risch T. The use of nest boxes to sample arboreal vertebrates. Southeast Naturalist. 2005;4:447–459.

- Loretto D, Vieira M. Artificial nests as an alternative to studies of arboreal small mammal populations: a five-year study in the Atlantic Forest, Brazil. Zoologia (Curitiba). 2011;28:388–394.

- Truszkowski J. Utilization of nest boxes by rodents. Acta Theriol. 1974;19:26–33.

- Sanz V, Rodríguez-Ferraro A, Albornoz M, et al. Use of artificial nests by the yellowshouldered parrot (Amazona barbadensis). Ornitol Neotrop. 2003;14:345–351.

- Celis-Diez JL, Hets J, Marín-Vial PA, et al. Population abundance, natural history, and habitat use by the arboreal marsupial Dromiciops gliroides in rural Chiloé Island, Chile. J Mammal. 2012;93:134–148.

- Waltman JR, Beissinger S. Breeding behavior of the Green-rumped Parrotlet. Wilson Bull. 1992;104:65–84.

- Sandercock B, Beissinger S, Stoleson S, et al. Survival rates of a neotropical parrot: implications for latitudinal comparisons of avian demography. Ecology. 2000;81:1351–1370.

- Sánchez-Azofeifa GA, Quesada M, Rodríguez JP, et al. Research priorities for neotropical dry forests. Biotropica. 2005;37:477–485.

- Horstman E. Establishing a private protected area in ecuador: lessons learned in the management of cerro blanco protected forest in the city of Guayaquil. Case Stud Environ. 2017;1:1–14.

- Quiroga M, Reboreda J, Beltzer A. Host use by Philornis sp. in a passerine community in central Argentina. Rev Mex Biodiv. 2012;83:110–116.

- Bulgarella M, Quiroga M, Brito G, et al. Philornis downsi (diptera: muscidae), an avian nest parasite invasive to the Galápagos Islands, in mainland Ecuador. Ann Entomol Soc Am. 2015;108:242–250.

- Tirira D. Guía de campo de los mamíferos del Ecuador. Publicación especial sobre los Mamíferos del Ecuador N°11. Ediciones Murciélago Blanco Ecuador; 2017.

- Dalloz M, Loretto D, Papi B, et al. Positional behaviour and tail use by the bare-tailed woolly opossum Caluromys philander (didelphimorphia, didelphidae). Mammal Biol. 2012;77:307–313.

- Monticelli P, Gasco A. Nesting behavior of Didelphis aurita: twenty days of continuous recording of a female in a coati nest. Biota Neotropica. 2018;18:3.

- Rossi R, Voss R, Lunde D. A revision of the didelphid marsupial genus Marmosa part 1. The species in tate’s ‘mexicana’and ‘mitis’ sections and other closely related forms. Bull Am Mus Nat Hist. 2010;334:1–83.

- Voss R, Gutiérrez S, Solari R, et al. Phylogenetic relationships of mouse opossums (Didelphidae, Marmosa) with a revised subgeneric classification and notes on sympatric diversity. Am Mus Novit. 2014;3817:1–28.

- Vallejo AF, Tirira DG, Carrión Bonilla C. Marmosa simonsi. In: Brito J, Camacho MA, Romero V, et al., editors. Mamíferos del Ecuador. Version 2018.0. Museo de Zoología, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador; 2021. [Accessed 2021 Dec 7]. https://bioweb.bio/faunaweb/mammaliaweb/FichaEspecie/Marmosa%20simonsi

- Enders R. Mammalian life histories from Barro Colorado Island, Panama. Bull Mus Comp Zool. 1935;78:385–497.

- Hunsaker D, Shupe D. Behavior of new world marsupials. In: Hunsaker IID, editor. The biology of marsupials. New York: Academic Press; 1977. p. 279–344.

- O’Connell MA. Marmosa robinsoni. Mamm Species. 1983;203:1–6.

- Enders RK. Attachment, nursing, and survival of young in some didelphids. Symp Zool Soc Lond. 1966;15:195–203.

- O’Connell MA. Ecology of didelphid marsupials from Northern Venezuela. In: Eisenberg JF, editor. Vertebrate ecology in the Northern Neotropics. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution Press; 1979. p. 73–87.

- Bravo R Diversidad y abundancia de micromamíferos terrestres (Clase: Mammalia) en zonas con distintos grados de perturbación en el Bosque Protector Cerro Blanco. Bachelor’s thesis. Universidad de Guayaquil, Guayaquil Ecuador. 2017.

- Montenegro-Díaz O, López-Arévalo H, Cadena A. Aspectos ecológicos del roedor arborícola Rhipidomys latimanus Tomes, 1860, (Rodentia: cricetidae) en el oriente de Cundinamarca, Colombia. Caldasia. 1991;16:565–572.

- Vallejo AF, Boada C. Rhipidomys. In: Brito J, Camacho MA, Romero V, et al., editors. Mamíferos del Ecuador. Version 2018.0. Museo de Zoología, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador; 2021. [Accessed 2021 Dec 7]. https://www.bioweb.bio/faunaweb/mammaliaweb/ListaEspeciesPorFamilia/172

- López Arévalo H, Montenegro Díaz O, Cadena A. Ecología de los pequeños mamíferos de la Reserva Biológica Carpanta, en la Cordillera Oriental Colombiana. Stud Neotrop Fauna Environ. 1993;28:193–210.

- Delgado C, Arias A, Aristizábal S, et al. Uso de la cola y el marsupio en Didelphis marsupialis y Metachirus nudicaudatus (Didelphiomorphia: didelphidae) para transportar material de anidación. Mastozool Neotrop. 2014;21:129–134.

- Lindenmayer D, Welsh A, Donnelly C, et al. Are nest boxes a viable alternative source of cavities for hollow-dependent animals? Long-term monitoring of nest box occupancy, pest use and attrition. Biol Conserv. 2009;142:33–42.