Abstract

Facial nerve palsy involves a wide spectrum of etiologies. The most common cause of peripheral facial palsy is Bell’s palsy. Facial nerve neoplasm is a rare cause of facial palsy. A 56-year-old male patient presented with a gradual onset of peripheral-type right facial palsy and with a finding of facial nerve mastoid segment tumor by magnetic resonance imaging. Surgical exploration showed no tumor tissue, but there was granulation surrounding a segment of an atrophic facial nerve. Pathology revealed fibrosis mixed with granulation, and virologic analysis was negative for herpes simplex virus. Facial palsy is a challenging issue. Suspicion of a facial neoplasm at a rare location and isolated segment raised the differential diagnosis of uncommon facial nerve lesions. Surgical exploration could not categorize the lesion into infection, neoplasm, or trauma. Further studies on similar patients may define this as a completely new disease in the future.

Introduction

The clinical course for facial palsy can be divided into three categories: sudden, delayed, or gradual. Sudden onset of an acute deterioration of facial nerve function is usually diagnosed within a few days and can result from an infectious process or trauma. The delayed type is defined by an apparent event occurred days before the onset of facial weakness, though facial function is normal immediately following the event. This kind of facial palsy may refer to an occult temporal bone fracture involving the facial canal. No obvious disruption or transections of the nerve fiber is noted on the high-resolution images, however, facial palsy develops 1 or 2 days after the traumatic event due to the epineurium swelling and compression. A facial palsy with a gradual onset clinical course refers to a progressive loss of function in weeks to months of timeframe.[Citation1,Citation2] Facial nerve neoplasm is a relatively rare cause of facial nerve palsy, and according to a previous study, 95% of it was presented with a gradual character of disease course.[Citation3] In addition to the gradual-onset nature, some of the following clinical histories made clinicians more suspicious for a facial nerve neoplasm: (1) no spontaneous recovery after 2–3 months of observation; (2) a recurrent attack of ipsilateral facial paresis; (3) coexistence of facial twitching with persistent exacerbation of facial function; and (4) multiple cranial nerve involvement.[Citation2,Citation4]

In this case report, we will present a patient with a very typical tumor-suspicion past history of facial nerve palsy, who was eventually proved to be tumor-free, but fibrosis. The clinical findings including electrophysiological test, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), temporal bone high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT), surgical findings, final pathologic report, and viral analysis will be discussed.

Case report

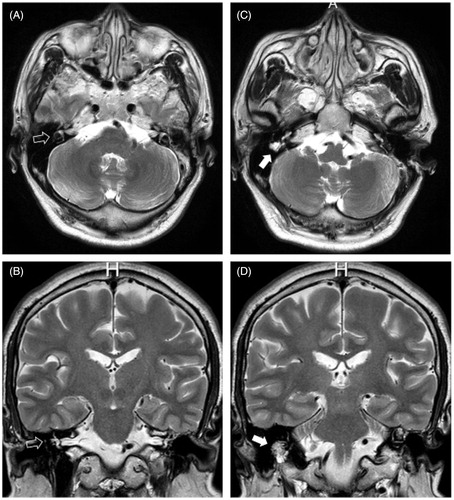

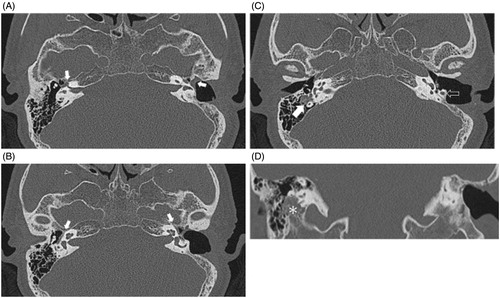

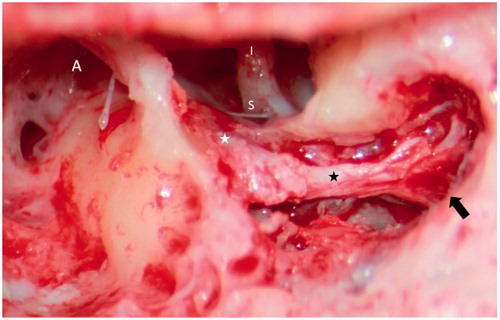

On March 2015, we encountered a 56-year-old male patient who was presented with a right facial palsy persisted for over 1 year. He once underwent a left tympanoplasty and mastoidectomy 20 years ago, but denied any other underlying diseases. The disease course for his right facial weakness was subtle at first, with only delayed eye blinking and mouth angle depressing occasionally. He did not visit a neurologist or otolaryngologist for evaluation until the weakness progressed to total palsy, for about 4 months after the onset. During this 3–4 months period, he also experienced right hemi-facial twitching, tingling pain, and dysesthesia over the right postauricular area. There were no specific audiologic complaints such as hearing impairment, tinnitus, aural fullness, or hyperacusis. Before he visited the neurologist at our hospital, he had attempted only Chinese herbal medicine and acupuncture. In the neurologic clinic, a House–Brackmann grade VI right facial palsy was recorded. Electrophysiological test for facial nerve function showed an absence of facial stimulation amplitude and a blink reflex. Electromyography indicated no spontaneous voluntary motor units firing, implying a total degeneration of facial nerve function. The presenting clinical course fulfilled the criteria for a possible facial tumor with the gradual onset of a facial palsy over a 3-week period and facial twitching, so an MRI of the brain was performed. A high-signal lesion occupying the right facial nerve mastoid segment was demonstrated by T2-weighted MRI. The cisternal, meatal, labyrinthine, and tympanic segments were all free of contrast-enhancing lesions (). Then, he was referred to the otolaryngology clinic for further evaluation. We performed physical examination and audiology tests that indicated a normal external auditory canal and normal ear drum, with symmetric hearing above a 25 dB threshold. There was no mass or bulge over the right mastoid or parotid region. Temporal bone HRCT demonstrated normal contour and caliber of the facial canal from the meatal to pyramidal eminence that was comparable to the healthy side. However, upon entering the mastoid segment, a soft tissue density with erosion of the bony septum that surrounded the fallopian canal was noted down to the stylomastoid foramen (). As a facial nerve schwannoma involving the mastoid segment was suspected, informed consent for surgical exploration with possible tumor excision and interpositional graft was obtained. A traditional mastoidectomy with facial nerve decompression was performed to identify the incus, cochleariform process, and pyramidal eminence. The bony canal of the whole mastoid segment and distal tympanic segment of the right facial nerve were removed and decompressed (). Granulation tissue was noted in the widened facial canal during exploration. After debridement of the granulation tissue, the entire contour of the facial nerve was exposed, and an abnormal white, firm nerve texture was revealed and was connected to the normal tympanic segment that was purple, round, and elastic. No definite tumor was noted, and we excised a piece of the epineurium for pathologic, standard viral culture and herpes simplex virus PCR analyses. The final report showed fibrosis in both the epineurium and granulation tissue. And the viral analysis was negative for herpes simplex virus.

Figure 1. (A and B) A white empty arrow indicates the right horizontal semicircular canal with a hyperintense signal on T2-weighted imaging; no space-occupying lesion is seen at this level. The facial nerve and vestibulocochlear nerve can be clearly seen in the internal auditory canal. (C and D) A white arrow indicates a hyperintense lesion lying just lateral and inferior to the horizontal semicircular canal that occupied the original mastoid segment of the facial nerve.

Figure 2. (A) A white arrow indicating the labyrinthine segment of the facial nerve; they were comparable in caliber and contour bilaterally. (B) A white arrow indicates the tympanic segment of the facial nerve; a symmetrical shape and contour are noted. (C) A white arrow indicates the mastoid segment of right facial nerve; a widened fallopian canal filled with a soft tissue density is noted, as compared with the white empty arrow pointing to the left normal fallopian canal. (D) A coronary view of the temporal bone HRCT shows that the entire segment has been replaced by a soft tissue component that extends to the stylomastoid foramen (asterisk).

Figure 3. A traditional mastoidectomy approach was performed to decompress the facial nerve. Note the junction between the normal-appearing facial nerve and the atrophic or fibrotic part (from the white asterisk to the black asterisk). A black arrow indicates early bifurcation within the mastoid segment. A: antrum; S: stapes; I: incus.

During the follow-up duration up to 6 months, subjective improvement primarily on the eye blinking was told by the patient, however, objective scale improved little and the House–Brackmann score remained grade VI. No further associated symptoms such as neck mass or audiologic complaints were reported.

Discussion

Facial palsy is still a challenging clinical issue because of its complex pathophysiology and disease course. With the onset of an acute facial palsy within a couple of days, differential diagnosis could be limited to an infectious process or traumatic event.[Citation1,Citation2] Bell’s palsy, the most common cause of acute facial paralysis, is responsible for more than one-half of all cases, with a characteristic of minimal associated symptoms and spontaneous recovery. In a previous study, nearly 83% of the patients achieved a House–Brackmann grade I–II recovery within 2 months of disease onset.[Citation5,Citation6] Although Bell’s palsy involves the entire facial nerve, the most vulnerable segments are located at the narrowest part: the labyrinthine segment. It also has the weakest blood supply because both the end branches arise from the labyrinthine artery and the superficial petrosal branch of the middle meningeal artery anastomosed here.[Citation7,Citation8] In our case, the surgical findings showed an atrophic, fibrotic mastoid segment of the facial nerve that probably resulted from nerve swelling, edema, and eventual vascular thrombosis; however, this location is a rare surgical finding for idiopathic facial palsy. The other segments including the tympanic and labyrinthine segments were in good shape, as revealed during the decompression procedure. Murakami et al. studied the viral positivity rate of the facial nerve in 13 patients with Bell’s palsy and demonstrated that 10 patients had a positive result, as compared with none in the control group.[Citation5, Citation9, Citation10] To analyze the possible cause in our case, we sampled a piece of the epineurium of the facial nerve for herpes simplex virus type I and type II PCR test, which resulted in negative findings for both of them. For this patient, the disease course had a gradual onset that was accompanied by facial twitching, with a progression to grade VI palsy over a 4-month period. This is not similar to Bell’s palsy regarding the clinical presentation, radiologic findings, surgical findings, or viral analysis.

In a large case series on facial nerve schwannomas conducted in 2008, the most common presenting symptoms were hearing loss (58%) and facial weakness (51%).[Citation11] Entire nerve segments could be involved, and over one-half extended to more than one segment (50–74%).[Citation11,Citation12] MRI with contrast has become the gold standard for diagnosing facial nerve schwannomas, especially intra-canalicular lesions. On unenhanced T1-weighted MRI, schwannomas appear isointense or slightly hypointense, as compared with the brain, and a little hyperintense, as compared with cerebrospinal fluid. The tumor became hyperintense to the brain and isointense to the cerebrospinal fluid on T2-weighted MRI. In addition to MRI, HRCT could be applied to assist in evaluating the internal auditory canal and bony canal along the course of the vestibular or facial nerve.[Citation13] Any canal enlargement or bony erosion would raise suspicion of a tumor with mass effect.[Citation7,Citation13] In our case, the patient presented with no specific audiologic complaints, and pure tone audiometry indicated symmetric hearing. MRI revealed an obvious irregular hyperintense lesion occupying the right mastoid segment of the facial nerve per a T2-weighted image that was highly suspicious for a schwannoma. Temporal bone HRCT confirmed bony erosion inside the mastoid bone. According to the conclusion of McMonagle et al., for a facial nerve schwannoma with deteriorated facial nerve function to a House–Brackmann grade IV or worse, surgical intervention is suggested.[Citation11] We performed a decompression surgery and determined that all the radiologic findings resulted from severe granulation, facial nerve atrophy, and fibrosis, with a widened and eroded fallopian canal. No apparent tumor tissue was noted.

Reviewing the case series, case reports, and images published in recent decades, no single case presented with similar characteristics that mimicked a tumor as in this case. We recorded the clinical presentation, images, electrophysiologic report, surgical images, and pathology report to present this rare and interesting case. A pathophysiologic origin with severe fibrosis was idiopathic in nature, and we could not categorize it as related to an infection, a neoplasm, trauma, or a metabolic origin. Perhaps this incidental finding will prove to be of a new disease entity in the future, after the discovery of additional cases of similar nature.

Ethical Standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the Shin-Kong Wu-Ho-Su Memorial Hospital guidelines on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Funding information

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- Pitts DB, Adour KK, Hilsinger RL. Recurrent Bell's palsy: analysis of 140 patients. Laryngoscope. 1988;98:535–540.

- Lauman EPJ, Jongkees LBW. On the prognosis of peripheral facial paralysis of endotemporal origin. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1963;72:621–636.

- Vrabec JT, Guinto F Jr, Nauta HJ. Recurrent facial neuromas. Am J Otol. 1998;19:99–103.

- Kirazli T, Oner K, Bilgen C, et al. Facial nerve neuroma: clinical, diagnostic, and surgical features. Skull Base. 2004;14:115–120.

- Makeham TP, Croxson GR, Coulson S. Infective causes of facial nerve paralysis. Otol Neurotol. 2007;28:100–103.

- Peitcrsen E. Bell's palsy: the spontaneous course of 2,500 peripheral facial nerve palsies of different etiologies. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 2002;549:4–30.

- Murai A, Kariya S, Tamura K, et al. The facial nerve canal in patients with Bell’s palsy: an investigation by high-resolution computed tomography with multiplanar reconstruction. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;270:2035–8.

- Mavrikakis I. Facial nerve palsy: anatomy, etiology, evaluation, and management. Orbit. 2008;27:466–74.

- Xu F. Sternberg MR, Kottiri BJ, et al. Trends in herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2 seroprevalence in the United States. JAMA. 2006;296:964–97.

- Murakami S, Mizobuchi M, Nakashiro Y, et al. Bell palsy and herpes simplex virus: identification of viral DNA in endoneurial fluid and muscle. Ann Intern Med. 1996;124:27–30.

- McMonagle B, Al-Sanosi A, Croxson G, et al. Facial schwannoma: results of a large case series and review. J Laryngol Otol. 2008;122:1139–1150.

- Liu L, Xiang D, Li Y, Sun J. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of intratemporal facial nerve neurofibromas. Am J Otolaryngol. 2015;36:565–567.

- Gupta S, Mends F, Hagiwara M, et al. Imaging the facial nerve: a contemporary review. Radiol Res Pract. 2013;2013:248039.