Abstract

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a rare idiopathic disorder that results in tissue destruction due to the intense and abnormal proliferation of histiocytes. It affects numerous organs, but isolated mandibular osteolysis has not been previously reported as an initial manifestation of this disease. This paper aims to describe an unusual presentation of LCH in the mandible of a 10-year-old girl initially assessed to have Gorham’s disease based on clinical and imaging findings. Computerized tomography (CT) scan and MRI showed extensive lysis and resorption of the mandible, with note of a contrast-enhancing soft-tissue mass in the right maxillary sinus. Incisional biopsy and histopathologic examination were performed, and the diagnosis of LCH was established and confirmed by S100 and CD1-a immunostaining positivity. The patient underwent chemotherapy with vinblastine and prednisone which eventually resulted in reconstitution of the patient’s mandible. LCH should be considered as a differential in a patient presenting with signs and symptoms of Gorham’s disease.

Introduction

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a rare idiopathic disorder characterized by intense and abnormal proliferation of bone marrow-derived histiocytes, ultimately leading to tissue destruction. It predominantly affects children, with an incidence of 10 per million children aged ≤15 years, and has a predilection for males compared to females (2:1).[Citation1] LCH is clinically divided into three groups: single system, low-risk multisystem and multisystem with risk-organ involvement. Single-system LCH can involve a single site (unifocal) or multiple sites (multifocal) of different organ systems, while multisystem LCH is characterized by involvement of two or more organs/systems, with or without involvement of risk organs. Risk organs include the bone marrow, liver and/or spleen, and denote a poorer prognosis.[Citation2] Though numerous organs are affected: bones, skin, liver, spleen, lymph node, lung and brain, the majority of reported cases involve the head and neck region.[Citation1] However, isolated mandibular resorption has not been previously cited in available literature as a manifestation of this disease. Thus, we are prompted to report the rare case of a 10-year-old girl who presented with mandibular resorption, the diagnostic dilemma that arose, and the resolution of disease.

Case report

A 10-year-old girl sought consult at a local dental clinic, complaining of a 1 week history of progressive swelling over the right mandible. Her parents reported that she had intermittent low grade fever and throbbing pain in the right mandibular region, with tenderness upon palpation. On oral examination, the dentist noted a carious tooth centered on the swollen area, with no other pertinent findings. The patient was managed as a case of dentoalveolar abscess and started on oral antibiotics. Tooth extraction done during the subsequent visit provided resolution of symptoms.

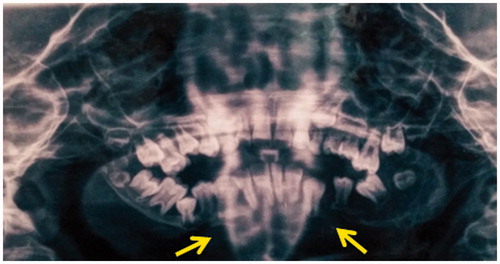

After an unremarkable year, the parents noted new-onset tumefaction on the patient’s right mandible, corresponding to the site of previous tooth extraction. No fever, pain, functional impairment or forswearing inflammatory signs were elicited. Eventually, there was note of loosening dentition and a retruding jaw. The parents brought her to another dentist who requested a panoramic radiograph, revealing osteolysis of the mandible from the right body to the left body, with complete loosening and malposition of all the lower teeth (Figure ). The patient was then referred to a local otorhinolaryngologist who immediately referred her to our institution for further work-up and management.

Upon admission, extra-oral examination revealed a significantly retruded chin, mild diffuse swelling on both sides of the jaw, and normal overlying skin (Figure ).

Intraoral examination revealed a partially edentulous mandible with several missing molars and carious teeth. There were no masses observed intraorally, and no abnormal changes in the oral mucosa. Palpation did not elicit local tenderness. There were no clinically palpable cervical lymphadenopathies. No trismus was noted, but mild malocclusion was evident.

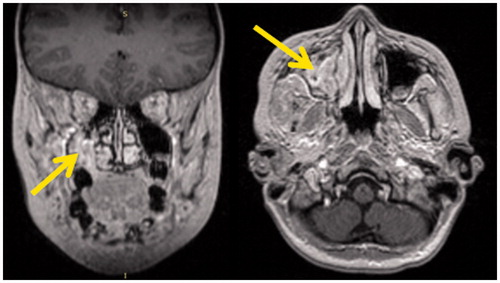

A facial computerized tomography (CT) scan was requested, revealing mandibular osteolysis, with note of suspicious fluid/soft-tissue densities within the right maxillary sinus (Figure ). With these imaging findings, Gorham’s disease was suspected as the patient fulfilled six out of eight of the diagnostic criteria for this condition, namely osteolytic radiographic pattern, nonexpansile nonulcerative lesion, evidence of local progressive resorption, absence of visceral involvement, minimal or no osteoblastic response and absence of dystrophic calcification, and no hereditary, metabolic, neoplastic, immunogenic or infectious etiology (Table ). Other considerations were ameloblastoma, which would typically present with expansile uni- or multilocular radiolucent lesions,[Citation3] and cherubism, which would present with expansile multilocular lytic lesions secondary to bony replacement by fibrous tissue.[Citation4]

Table 1. Histopathologic and clinical criteria for Gorham’s diseases.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was done for better delineation of the lesion. Findings showed that the densities initially noted within the right maxillary sinus on CT scan actually represented a soft-tissue mass (Figure ). An incisional biopsy of the said mass was subsequently performed using the Caldwell–Luc approach, yielding the specimen of a soft, fleshy, pinkish, friable mass.

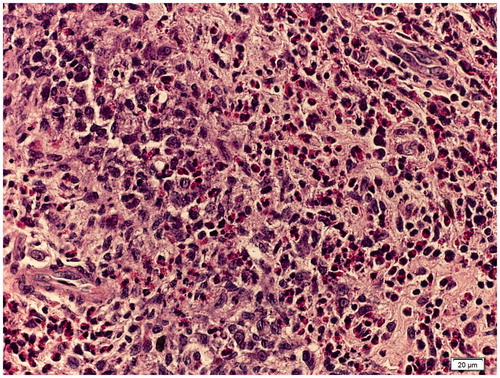

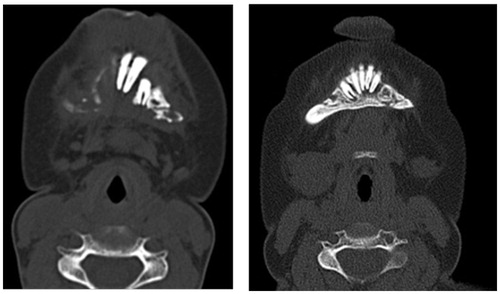

Histopathologic examination revealed clusters and sheets of histiocytes and infiltrating clusters of eosinophils suggestive of LCH (Figure ). Immunochemistry staining for both S100 and CD1-a confirmed the impression. To evaluate the entirety of the disease, multiple diagnostics were performed to rule out involvement of other parts of the body. Chest radiograph, skeletal survey, urinalysis, bone marrow aspirate and abdominal ultrasound were done, all of which turned out to be negative. Having localized the disease to the maxillofacial skeleton, the patient was treated as a case of single-system multifocal LCH. The patient underwent a 16-week chemotherapy regimen with vinblastine 6 mg/m2 IV bolus and prednisone 40 mg/m2/day orally with note of subsequent slow reconstitution of her mandible (Figure ). During chemotherapy, the patient did not experience any oral or systemic side effects.

Discussion

Langerhans cell histocytosis, previously known as histiocytosis X, eosinophilic granuloma, Letterer–Siwe disease, Hand–Schuller–Christian disease, and diffuse reticuloendotheliosis, is a rare disorder in which proliferation of pathologic Langerhans cells leads to either focal or systemic tissue infiltration and destruction. Its etiology remains controversial. Some studies suggest that it is caused by an immunologic dysfunction secondary to suppressor cell deficiency.[Citation5] New researches, however, report the involvement of a cancer-associated mutation (BRAFV600E), concluding that LCH may be a neoplastic process.[Citation6]

LCH may affect various systems in the body, but the skeletal system is most commonly involved in both unifocal and multifocal groups. In fact, in 60% of all cases, it is the only system involved.[Citation7] The disease may affect any osseous structure, but the skull, pelvis, femur, ribs and humerus are the more common sites. The incidence of mandible involvement is relatively low at 7.9%, and in these cases, the mandibular body and angle are usually affected.[Citation8]

LCH most frequently presents with oral cavity symptoms, which are seen in 77% of cases.[Citation8] The oral cavity may be the earliest, or even the only region involved. In published literature, reported signs and symptoms include loosening of the teeth, orofacial pain and swelling, mucosal ulceration, gingival necrosis and bleeding, erythematous masses, periodontitis, candidiasis and precocious eruption of teeth.[Citation8] Mandibular involvement has been described, but in association with other clinical manifestations, and in patients over 20 years of age. Extensive literature search did not yield any report of isolated mandibular resorption in this disease. Thus, a finding of isolated mandibular resorption in a 10-year-old girl does not immediately imply a case of LCH.

With only 200 reported cases worldwide, Gorham’s disease, characterized by Lemuel Whittington Gorham and Arthur Purdy Stout in 1955, is a very rare condition.[Citation9] It is a bone disorder characterized by spontaneous and progressive osteolysis, most commonly affecting the mandible. At present, though there is no established consensus on the pathophysiology and management of this illness, eight diagnostic criteria have been suggested [Citation10] (Table ). The patient, whose clinical presentation is similar to majority of the published cases, satisfied six of the eight criteria. This posed a major clinical dilemma: should the patient, a 10-year-old child, undergo a biopsy to confirm the diagnosis of Gorham’s disease even if she exhibits the typical presentation of this condition, as described by several published studies?[Citation11]

After a thorough discussion of the risks and benefits of the procedure with the patient’s parents, an incisional biopsy was eventually performed. The histopathologic findings of clusters and sheets of histiocytes and infiltrating clusters of eosinophils suggested the diagnosis of LCH (Figure ). There was no histopathologic evidence of angiomatosis, ruling out Gorham’s disease. Immunochemistry staining for both S100 and CD1-a confirmed this as a case of LCH.

Both Gorham’s disease and LCH are rarely encountered, but the importance of distinguishing between these two diseases lies in their very different management. The treatment for LCH necessitates chemotherapy, while Gorham’s disease requires careful monitoring, radiotherapy and even surgery. We therefore suggest that if a similar case of isolated mandibular osteolysis is encountered in our practice as otorhinolaryngologists, LCH should always be considered a possibility.

It is hoped that this case report will help the clinician in decision-making with regards to diagnosis and management, as early detection is paramount in preventing disease progression with timely definitive treatment.

Notes on contributors

Alexander Edward S. Dy, MD, Senior Resident, Department of Otorhinolaryngology, University of the Philippines, Philippine General Hospital.

Arsenio Claro A. Cabungcal, MD, Residency Training Officer, Department of Otorhinolaryngology, University of the Philippines, Philippine General Hospital, and Clinical Associate Professor, College of Medicine, University of the Philippines, Manila.

Roberto M. Pangan, DMD, MD, Section Chief, Cranio-maxillofacial Plastic and Restorative Surgery Section, Department of Otorhinolaryngology, University of the Philippines, Philippine General Hospital, Manila.

References

- Guyot-Goubin A, Donadieu J, Barkaoui M, et al. Descriptive epidemiology of childhood Langerhans cell histiocytosis in France, 2000–2004. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;51:71–75.

- Elia D, Torre O, Cassandro R, et al. Pulmonary langerhans cell histiocytosis: a comprehensive analysis of 40 patients and literature review. Eur J Intern Med. 2015;26:351–356.

- Payne SJ, Albert TW, Lighthall JG. Management of ameloblastoma in the pediatric population. Oper Tech Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;26:168–174.

- Leyva PD, Eslava JM, Sales-Sanz M, et al. Comprehensive surgical management of cherubism with orbital involvement. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2015;27:503–507.

- Egeler RM, Favara BE, van Meurs M, et al. Differential in situ cytokine profiles of Langerhans-like cells and T cells in Langerhans cell histiocytosis: abundant expression of cytokines relevant to disease and treatment. Blood. 1995;94:4195–4201.

- Badalian-Very G, Vergilio JA, Fleming M, et al. Pathogenesis of Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Annu Rev Pathol. 2013;8:1–20.

- Miyamoto H, Dance G, Wilson DF, et al. Eosinophilic granuloma of the mandibular condyle. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2000;58:560–562.

- Anniballi S, Cristalli MP, Solidani M, et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: oral/periodontal involvement in adult patients. Oral Dis. 2009;15:596–601.

- Gorham LW, Stout AP. Massive osteolysis (acute spontaneous absorption of bone, phantom bone, disappearing bone); its relation to hemangiomatosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1955;37:985–1004.

- Heffez L, Doku HC, Carter BL, et al. Perspectives on massive osteolysis. Report of a case and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1983;55:331–343.

- Escande C, Schouman T, Françoise G, et al. Histological features and management of a mandibular Gorham disease: a case report and review of maxillofacial cases in the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;106:30–37.