Abstract

Small-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (SNEC) is a distinct tumoral entity characterized by rapid local invasion, widespread dissemination and a poor prognosis. Due to its late discovery, localization is rarely precise.

We report a case of a 39-year-old man whose clinical symptoms, radiological findings histological diagnosis and immunohistochemical staining confirm a primary SNEC of the nasal septum. Clinical features of nasal SNEC are nonspecific, including those resembling benign lesions; hence, it is likely to result in a delay in its discovery and treatment. Distinction between SNEC and other neuroendocrine tumors is also of great importance because of its prognostic implication, being SNEC the most aggressive in this group. Surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy alone or in combination have been used for these patients. Unfortunately, due to the rarity of this neoplasm, there is no specific recommendation on management guidelines, and treatment possibilities should be individualized for each patient.

Introduction

Small-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (SNEC) also known as oat cell carcinoma is a distinct tumoral entity characterized by rapid local invasion, widespread dissemination and a deficient prognosis. SNEC found in extrapulmonary locations account for less than 4%.[Citation1–3] The association between the paraneoplastic endocrine syndrome and SNEC is clearly reported. Since it was first described and reported in 1965, a 50-year period, less than 100 cases have been described in the nose and paranasal sinuses.[Citation2–5]

Case report

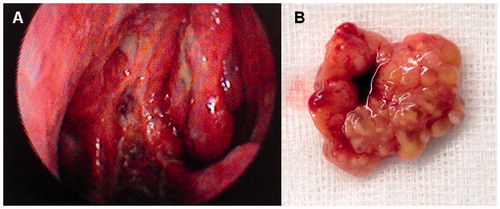

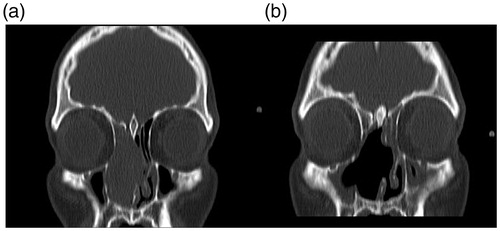

We present a case of a 39-year-old man with a 4-month history of nasal hydrorrhoea, nasal congestion and hyposmia. Regarding his medical history, the patient denied any disease, medication, smoking, drinking and exposure to radiation or environmental irritants. No history of epistaxis was mentioned although scarce staining of mucus happened occasionally. Physical examination revealed a whitish, friable and hemorrhagic tumor in the right fossa. No septal cartilage erosion with mass going to opposite nostril was observed. There were no associated neurological or eye-related symptoms, and both neurological and eye examinations were normal. No obvious cervical lymph nodes were noted and no distant metastasis was found. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) showed a mass in the right fossa occupying the anterior ethmoid sinus, obstructing the inferior and middle meatus, leading to mucous retention in the posterior ethmoid cells and sphenoid sinus (Figure ). A multidisciplinary approach was adopted. Endoscopic complete resection was carried out. Debulking of the tumor carried out in order to define the site of origin, showed that the tumor arose from the middle part of the nasal septum. Intraoperatively, a frozen section pathological assessment confirmed negative excision margins. The patient also received postoperative radio and chemotherapy.

Figure 1. Contrast-enhanced coronal CT preoperative image (A) showing an expansive homogeneous mass located in the right nasal fossa with ethmoid sinus and septal involvement. No bone erosion is observed. (B) Postoperative CT scan.

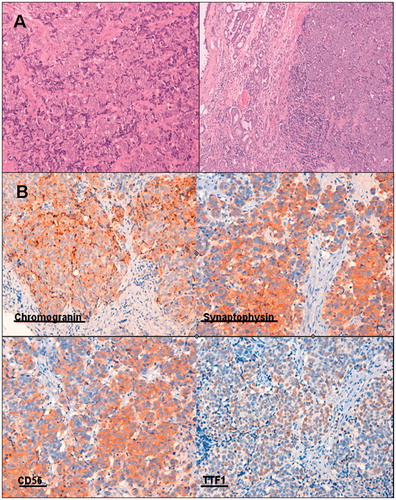

Histological diagnosis revealed sheets and nests of tumor cells with large nuclei, salt-pepper chromatin, inconspicuous nucleoli, little cytoplasm and the absence of sustentacular cells (Figure ). Lymph-vascular spaces and perineural invasion was evidenced. Immunohistochemical staining was performed on the formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections that were AE1-AE3 positive, chromogranin positive and synaptophysin positive. Grimelius argentic staining revealed the cytoplasmic neurosecretory granulation characteristic of the neuroendocrine nature.

Figure 2. (A) Diffuse proliferation of small to intermediate sized cells with very scant cytoplasm and oval to round hyperchromatic nuclei. (B) Immunohistochemistry showing chromogranin, synaptophysin, CD 56 and TTF1 positivity.

He is currently symptom free with no evidence of recurrence in clinical and radiological follow-up for close to 5 years now (Figure ).

Discussion

SNEC is an exceptional and aggressive lesion. The clinical features of SNEC of the nasal and paranasal sinuses are nonspecific and similar to those of other tumor types in this region, including benign lesions; hence, it is likely to result in a delay for its discovery and treatment. Hypotheses about the origin of SNEC in the nasal and paranasal cavities are various. Three different possibilities have been proposed. An epithelial origin deriving from mucoserous glands, associated with the existence of accessory ectopic salivary glands and a third hypothesis of a possible origin from basal cells in the olfactory mucosa.[Citation2,Citation6]

Diagnosis of SNEC requires a typical neuroendocrine histological constitution and proper immunohistochemical recognition.[Citation1,Citation4] Histologically, it may be very similar to small-cell tumors of the lung, but clinically, it has an aggressive local behavior instead of early metastatic spread.[Citation3] They are characterized for having a high mitotic rate, sheets and nests of cells with a large nuclei and scarce cytoplasm like in our case.[Citation3,Citation4] Immunohistochemistry in SNEC has been demonstrated that shows strong positivity for CD56 and synaptophysin and weak for chromogranins and CAM5.2/AE1 (stain), immunohistochemical findings described in our patient. No S-100-positive cells are found.[Citation1,Citation3,Citation4]

Distinction between SNEC and other neuroendocrine tumors, such as carcinoid tumors and an atypical carcinoid tumor is also of great importance because of its prognostic implication; SNEC being the most aggressive in this group.[Citation1,Citation5,Citation6] Radiological imaging is imperative to certify loco-regional invasion, bone destruction and presurgical planning.[Citation2] Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with T1 and T2 with gadolinium helps identify the tumoral relationship with surrounding structures and differentiate between inflammatory reactions and liquid retentions. CT scans are useful to distinguish a possible osteolytic lesion.[Citation5] Clinical features are not distinctive from other tumoral lesions in these locations. They include epistaxis, nasal obstruction and ophthalmologic signs such as proptosis.[Citation3–6]

Association with ectopic hormone syndrome has been described for SNEC and has a negative influence on prognosis as it does in pulmonary small cell carcinomas.[Citation1,Citation5]

Surgery usually followed by radiotherapy, or the combination of radio and chemotherapy are valid therapeutic options.[Citation1,Citation2,Citation6] Our patient underwent endoscopic resection and adjuvant postoperative chemoradiotherapy. Global prognosis of SNEC is quite poor.[Citation2,Citation3,Citation5] Early excision is imperative for best survival rates. Local recurrence has been reported to occur in up to 70% of the cases. Radiotherapy has been described as a possible option in treatment. It has shown to have better results in other head and neck sites than in the nasal cavity.[Citation6,Citation7] Unfortunately, due to the rarity of this neoplasm, there are no specific recommendations or management guidelines, and treatment possibilities are individualized for each patient and usually treated as conventional squamous cell carcinomas.[Citation4,Citation6]

Numerous studies [Citation7–9] have demonstrated the rarity of this lesion found in the nasal cavity as well as their prognosis regarding different treatments. The University of Miami treated 12 patients between 1987 and 2007 (20 years) with nonmetastatic small-cell carcinoma of the head and neck region. Two in the nasopharynx, one in the maxillary sinus, four in the parotid region, three in the tonsils, one in the supraglottic larynx and one in the nasal cavity. They believe radiotherapy and chemotherapy may be an adequate alternative to surgery obtaining better results in the tonsillar and parotid region than in the sinonasal area probably requiring a more aggressive treatment.[Citation7] A 10-year study was performed in Berlin (from 1998–2007) identifying 28 patients with extrapulmonary primary small-cell carcinoma only four being found in the paranasal sinuses and none in the nasal septum.[Citation8] Fifteen patients had locoregional disease (LD) and 13 had distant metastatic (DM) disease. They concluded that multimodal therapy can achieve an adequate control and prolonged survival in patients with LD. Nevertheless, survival in patients with DM can be compared with DM in small-cell lung carcinoma.[Citation8] One of the largest series published with reference to extrapulmonary SNEC was a 34-year study, from 1970 to 2004, carried out in England comparing the incidence and survival rate of extrapulmonary SNEC with small-cell carcinoma of the lung and to determine the most common primary extrapulmonary sites and their survival regarding disease stage and site.[Citation9] A total of 1618 patients were found with extrapulmonary SNEC, of which only 182 belonged to head and neck region and 19 to sinonasal area. Of the 182 patients with a SNEC in the head and neck region 64 had limited disease, 30 extensive disease and 88 unknown. Patients with breast SNEC had the best prognosis, while the ones in the gastrointestinal tract had the worst. The presenting site and the extent of the disease were the most sensitive predicting factors concerning survival.[Citation9]

The clinical features of SNEC of the nasal and paranasal sinuses are nonspecific and similar to those of other tumor types in this region, including benign lesions, hence is likely to result in a delay for its discovery and treatment. The prognosis of SNEC is poor and long-term follow-up is necessary. More extensive studies are needed to assess the optimal management and develop standardized treatment protocols.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

References

- Ma AT, Lei KI. Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the ethmoid sinuses presenting with generalized seizure and syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion: a case report and review of literature. Am J Otolaryngol. 2009;30:54–57.

- Tang IP, Singh S, Krishnan G, et al. Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses: a rare case. J Laryngol Otol. 2012;126:1284–1286.

- Han G, Wang Z, Guo X, et al. Extrapulmonary small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the paranasal sinuses: a case report and review of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;70:2347–2351.

- Iacovou E, Chrysovergis A, Eleftheriadou A, et al. Neuroendocrine carcinoma arising from the septum. A very rare nasal tumour. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2011;31:50–53.

- Chatterjee DN, Mondal A. Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of nose and paranasal sinuses: a study of three cases with short review of the literature. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;61:43–46.

- Renner G. Small cell carcinoma of the head and neck: a review. Semin Oncol. 2007;34:3–14.

- Hatoum GF, Patton B, Takita C, et al. Small cell carcinoma of the head and neck: the university of Miami experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;74:477–481.

- Ochsenreither S, Marnitz-Schultze S, Schneider A, et al. Extrapulmonary small cell carcinoma (EPSCC): 10 years’ multi-disciplinary experience at Charité. Anticancer Res. 2009;29:3411–3415.

- Wong YN, Jack RH, Mak V, et al. The epidemiology and survival of extrapulmonary small cell carcinoma in South East England, 1970-2004. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:209.