Abstract

Oral macule and mucosal melanoma are often difficult to differentiate from each other, and a conclusive diagnosis of mucosal melanoma is difficult to make, either clinically or pathologically, in younger adults. We report the case of a 26-year-old female who presented with a black pigmented lesion of the left upper gingiva. The lesion was finally diagnosed as a mucosal melanoma 10 months after the patient’s first visit to a hospital. She received partial left maxillectomy. She has been alive without active disease for 3 years after first operation. Considering that in general, subepithelial invasion is seen even from the early phase in cases of mucosal melanoma, prompt and precise pathological diagnosis is necessary to ensure appropriate therapy.

Introduction

Mucosal melanomas most often occur in the palate and gingiva, predominantly in aged males, and in general, they carry a much poorer prognosis than cutaneous melanomas.[Citation1–4] One of the reasons, why mucosal melanomas are difficult to diagnose promptly is that their clinical presentation is similar to that of oral macule;[Citation4] furthermore, the small biopsy specimens usually obtained from these pigmented lesions are often insufficient for a definitive pathological diagnosis, since several characteristic features may not be observable in such small-sized biopsy specimens. Opinions about the appropriate timing of incisional biopsy vary.[Citation1,Citation4–6] This case report is intended at establishing an appropriate diagnostic process for mucosal melanoma, including clarifying the appropriate timing for incisional biopsy, in cases clinically suspected as having mucosal melanoma, and also for clarifying the differential pathological findings between melanocytic nevi and mucosal melanomas. Moreover, we also discuss the most appropriate therapeutic strategies for mucosal melanomas. The rare case of mucosal melanoma in a young female that we report here provides some significant suggestions about the appropriate approach for a correct diagnosis of mucosal melanoma.

Case report

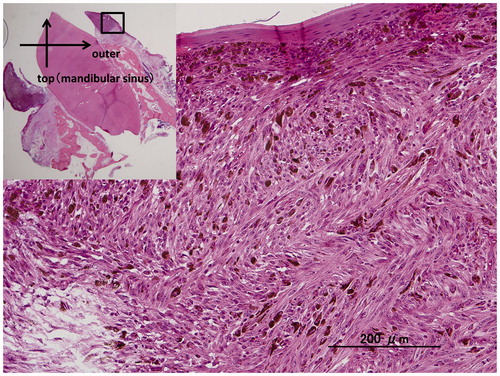

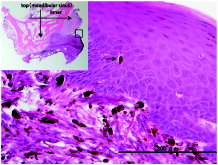

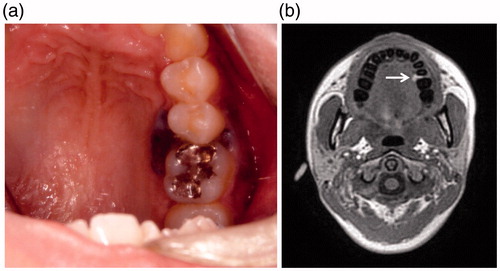

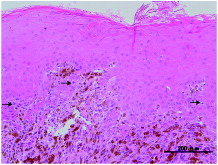

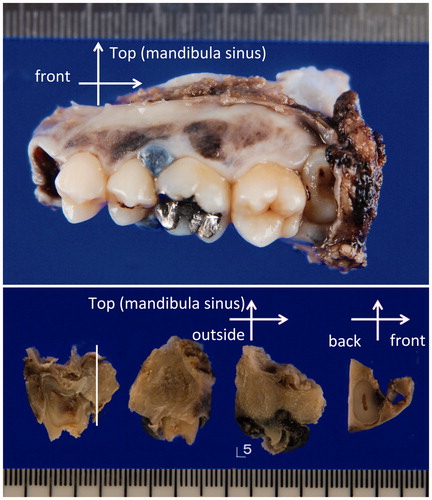

A 26-year-old female visited another hospital for medical examination when she noticed black pigmented lesion in the left upper gingiva. A cytology from fine needle biopsy was performed, which revealed a few atypical cells with mild cellular atypia (class II), without any definite malignant cells, therefore, the diagnosis of malignant melanoma was excluded. She was diagnosed with a melanomatic macule. The patient underwent a medical examination again at the same hospital 9 months later when she noticed increase in the size of the lesion, and also bleeding from the lesion. An intraoral physical examination at this time revealed a black lobulated bulging mass covered with oral squamous epithelium on the palatal aspect around the left upper gingiva (5th–6th) (Figure ). An incisional biopsy was performed immediately. Histopathological examination of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained sections showed disruption of the basal membrane of the epithelium and proliferating atypical cells containing rough and large brownish granules, suspected to be melanin, in the subepithelial region. Most of the atypical cells were regarded as melanophages, however, a few atypical cells with melanocytic granules were also observed in the basal layer. The pathologist at the previous hospital determined that the specimen was insufficient for arriving at a conclusive diagnosis of malignant melanoma. Therefore, a second incisional biopsy was performed, which revealed proliferating atypical cells with a few mitoses in the basal layer of the epithelium and the subepithelial region. A few atypical polygonal cells containing oval- to spindle-shaped nuclei with enlarged nucleoli and cytoplasm with melanocytic granules were also observed in the middle layer of the epithelium, which were regarded as ‘ascending melanocytes.’ A few mitotic or apoptotic cells were present in the intraepithelial or subepithelial regions, associated with melanoma cells (Figure ). The pathologist at the previous hospital made the final diagnosis of malignant melanoma on the second biopsy specimen. Then, the patient was referred to our hospital for therapy 10 months after her first visit to the previous hospital. The initial physical examination at our hospital revealed the black slightly bulging, mass in the upper left gingiva, without any obvious cervical lymph node enlargement suggesting lymph node metastasis of malignant melanoma. There were no obvious abnormalities on general physiological examination. She had no significant past medical or personal history. The same two biopsy specimens collected at the previous hospital were re-examined by the pathologist of our hospital, who made the diagnosis of malignant melanoma on both the biopsy specimens. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a bulging mass arising from the left upper gingiva that was visualized as a hyperintensity on T1WI. MRI after injection of gadolinium revealed no definite invasion of the mandible or bone marrow by the tumor cells, and no cervical lymph node swelling caused by tumor metastasis (Figure ). Based on these findings, the lesion was diagnosed preoperatively as a mucosal melanoma of the upper gingiva: cT3N0M0 (Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) 7th), cT3N0M0 (American Joint Committee of Cancer (AJCC) staging 7th). We performed partial left maxillectomy including the entire pigmented lesion, one month after her first visit to our hospital. Macroscopically, the surgically resected specimen was a black-brown solid bulging mass measuring 10 × 9 mm in size in the left upper gingiva (5th–6th), associated with black-to-brown spotty pigmentations on the lateral side (4th–7th) (Figure ). H&E-stained sections of this specimen showed proliferating spindle- to oval-shaped tumor cells containing rough and large melanin granules in the intraepithelial or subepithelial regions. Tumor cells spreading laterally were also observed in the basal layer of the epithelium (Figure ). A few proliferating tumor cells were found in the upper portion of the epithelium, which were regarded as ‘ascending melanocytes’ (Figure ). The maximum tumor depth was 7250 μm as measured at the section including the deepest portion of the tumor. There was erosion of the mandibular bone, but no invasion of the bone marrow by the tumor cells. No tumor cells were observed at the anterior or posterior cut ends. Immunohistochemical staining revealed positive staining for HMB-45 in the tumor cells. The final pathologic diagnosis was malignant melanoma (mucosal melanoma) of the upper gingiva. No evidence of lymphatic or venous infiltration of the tumor cells was observed. The pathological stage was pT3 according to both the UICC (7th edition) and AJCC classifications. Unfortunately, cervical lymph node enlargement was detected 6 months after the primary tumor resection, and left-side cervical lymph node dissection was performed. Bilateral lymph node metastases were again detected 11 months after the primary tumor resection, and bilateral cervical lymph node dissection was performed again. At present, 3 years since the primary tumor resection, the patient remains disease-free under interferon therapy including IFN/DAVF (Interferon β · Dacarbazine · Vincristine · Nimstine).

Figure 1. (a) Intraoral examination. A lobulated black bulging mass covered with squamous epithelium at the palatal aspect around left upper gingiva (5th–6th). (b) Magnetic resonance images (MRI). A bulging mass in the left upper gingiva, visualized as a hyperintensity on T1WI (both in-phase out-of-phase).

Figure 2. Microscopic photo of the second incisional biopsy specimen. Proliferating atypical oval- to spindle-shaped cells containing brownish granules suspected to be melanin in the lower layer of the squamous epithelium and subepithelium. The melanoma cells are scattered in the upper layer of the squamous epithelium (as shown with black arrows), which are regarded as ascending melanocytes.

Figure 3. (a) Macroscopic photo of the lateral view of the surgically resected specimen. A blackish-brownish bulging mass measuring 10 × 9 cm in the left upper gingiva (5th–6th), associated with blackish-brownish spotty pigmentations at the lateral side (4th–7th) are observed. (b) Sectioned view of the same specimen. The blackish-brownish color tumor located around the fifth tooth. The thickness of the tumor was determined to be less than 1 cm.

Discussion

Mucosal melanoma present as a blackish/brownish-colored bulging mass that shows pigmentation in most cases; about 15% of mucosal melanomas, however, do not show pigmentation.[Citation2] It has been reported that mucosal melanomas account for only 0.6% of all solitary pigmented melanocytic lesions, while melanosis or macule and nevus account for 86.1 and 11.8%, respectively.[Citation1] There are reports suggesting that melanoma accounts for only less than 0.5% of all oral malignancies.[Citation2] Mucosal melanomas have been reported to be seen predominantly in aged male patients, and to involve the palate and gingiva,[Citation4] however, mucosal melanoma still remains one of the differential diagnoses, on macroscopic appearance, of pigmented lesions encountered in young adults.

Our present case was slightly atypical, both from the point of view of age and that of gender. Cytological from fine needle biopsy was chosen as the first examination to confirm the diagnosis of mucosal melanoma; however, it did not yield the correct diagnosis at another hospital. Malignant melanoma presents at the epithelial-connective tissue interface, associated with upward migration into the epithelium and invasion of the underlying connective tissue. A report based on small numbers of samples suggested that incisional biopsy increases the risk of distant metastasis.[Citation6] If melanoma is suspected, complete excisional, not incisional, biopsy of the primary melanoma would be the first choice, which can provide sufficient specimens available for performing an accurate histopathologic diagnosis. On the other hand, a large but retrospective study reported that incisional biopsy exerted no influence on the disease-specific survival.[Citation1,Citation4,Citation7,Citation8] In cases, when performing an excisional biopsy is difficult, we would like to propose performing an incisional biopsy as the second choice rather than cytology. We would like to propose a simple approach to differentiate among black pigmented lesions, e.g. melanocytic nevus and malignant melanoma of the oral cavity. Asymmetrical appearance, irregular border, color variegation, larger in diameter than 6 mm, bulging mass appearance, presence of ulceration, and a history of growth of the lesion are characteristic signs of malignant melanoma. We would like to emphasize that incisional biopsy rather than cytology should be performed. Considering the poor prognosis of malignant melanoma, careful follow-up is needed, unless the possibility of the pigmented lesion being a malignant melanoma has been excluded completely.[Citation3–5]

The differential diagnoses of mucosal melanoma are melanosis, melanomatic macule, melanocytic nevus, and atypical melanocytic proliferation. Melanosis presents as slightly diffuse and patchy pigmentation, and is usually related to smoking and drinking. Melanomatic macules are most frequently found in oral black pigmented lesion that presents as segmented mucosal pigmentation and the condition never presents as a bulging mass. Nevi are hard to differentiate, because sometimes they present as a bulging mass. Nevocytes show cellular maturation with a direction, however, mucosal melanoma cells spread upward toward the epithelium and laterally and show invasive growth downward without cellular maturation, which are useful features to discriminate between melanocytic nevus and mucosal melanoma.

The reported disease-specific 5-year survival rate of patients with mucosal melanoma varies from 10 to 38%.[Citation4,Citation5,Citation9] Surgical resection still remains the primary treatment and radiation, and/or chemotherapy may serve as adjuvant therapies.[Citation1,Citation4,Citation5,Citation9,Citation10] Adjuvant treatment with interferon has been reported to provide substantial benefit in terms of the relapse-free survival in almost all the clinical trials of resected cutaneous malignant melanoma.[Citation11]

Conclusion

Diagnosis of mucosal melanoma at an early stage is considered to be necessary to initiate prompt and appropriate diagnosis and effective treatment. The experience with the present case suggests that active incisional biopsy should be highly recommended to obtain a correct diagnosis of mucosal melanoma, even in young females, because the surface of the lesion in the early stage is still covered with normal squamous epithelium.

Notes on contributors

Kenichi Kamizono and Satoshi Fujii gave a diagnosis pathologically. Motoyasu Katsura, and Ryuichi Hayashi treated the patient.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

References

- Buchner A, Merrell PW, Carpenter WM. Relative frequency of solitary melanocytic lesions of the oral mucosa. J Oral Pathol Med. 2004;33:550–557.

- Bujas T, Pavic I, Prus A, et al. Primary oral malignant melanoma: case report. Acta Clin Croat. 2010;49:55–59.

- Meleti M, Vescovi P, Mooi WJ, et al. Pigmented lesions of the oral mucosa and perioral tissues: a flow-chart for the diagnosis and some recommendations for the management. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;105:606–616.

- Shen ZY, Liu W, Bao ZX, et al. Oral melanotic macule and primary oral malignant melanoma: epidemiology, location involved, and clinical implications. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;112:e21–e25.

- Shuman AG, Light E, Olsen SH, et al. Mucosal melanoma of the head and neck: predictors of prognosis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;137:331–337.

- Umeda M, Komatsubara H, Shigeta T, et al. Treatment and prognosis of malignant melanoma of the oral cavity: preoperative surgical procedure increases risk of distant metastasis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;106:51–57.

- Pflugfelder A, Weide B Eigentler TK, et al. Incisional biopsy and melanoma prognosis: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28:316–318.

- Martin RC, Scoggins CR, Ross MI, et al. Is incisional biopsy of melanoma harmful? Am J Surg. 2005;190:913–917.

- Meleti M, Leemans CR, Mooi WJ, et al. Oral malignant melanoma: a review of the literature. Oral Oncol. 2007;43:116–121.

- Yii NW, Eisen T Nicolson M, et al. Mucosal malignant melanoma of the head and neck: the Marsden experience over half a century. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2003;15:199–204.

- Ascierto PA, Gogas HJ, Grob JJ, et al. Adjuvant interferon alfa in malignant melanoma: an interdisciplinary and multinational expert review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2013;85:149–161.