Abstract

Tilting and/or pulling sensation without a sensation of rotation might be caused by otolithic disorders and may be called otolithic vertigo. We report 3 children (a 5-year-old boy, a 15-year-old girl, and an 8-year-old boy) who presented with episodic tilting or pulling sensation in the roll plane. Common findings of these 3 patients were unilateral abnormal ocular vestibular evoked myogenic potential responses (oVEMP). They did not show any other abnormal findings, and were diagnosed as idiopathic otolithic vertigo (IOV). On the basis of their medical histories, their episodes might be caused by mechanism similar to migraine-associated vertigo.

Introduction

Murofushi et al. reported that patients who experienced episodic tilting sensations in the roll plane and episodic tilting or translational sensations in the pitch plane often display abnormal (absent or decreased) vestibular evoked myogenic potential (VEMP) responses.[Citation1,Citation2] They proposed that such patients should be diagnosed with idiopathic otolithic vertigo (IOV) provided they do not have definite diagnosis of other clinical entities, e.g. Meniere’s disease (MD).[Citation1–3] In their studies, the majority of patients with IOV diagnosed by diagnostic criteria constituted by symptoms and medical history showed absent or decreased responses of ocular VEMP (oVEMP) and/or cervical VEMP (cVEMP).[Citation1–4] Association between non-rotatory balance problems and otolithic dysfunction has also been reported by other investigators.[Citation5–7]

Pathophysiology of IOV still remains to be established. Murofushi et al. studied frequency preference (tuning) of cVEMP in IOV patients.[Citation3] They found that patients with larger responses at 1000 Hz than at 500 Hz, as patients with MD show, had tendency of longer duration of vertigo attacks (longer than 20 min) than patients without frequency preference of 1000 Hz. In other words, they suggested that the otolith organs of IOV patients who suffer relatively long vertigo attacks (longer than 20 minutes) might be affected by endolymphatic hydrops.[Citation3] The pathophysiology of IOV attacks with short duration is not known.

Although previous reports concerning IOV were done mainly in adult patients, recently we experienced IOV in children. Pediatric IOV patients showed some different tendency from adult patients. As pediatric cases might be suggestive for consideration of another pathophysiology, we herein report pediatric cases with IOV.

Report of cases

Patient #1 (a 5-year-old boy)

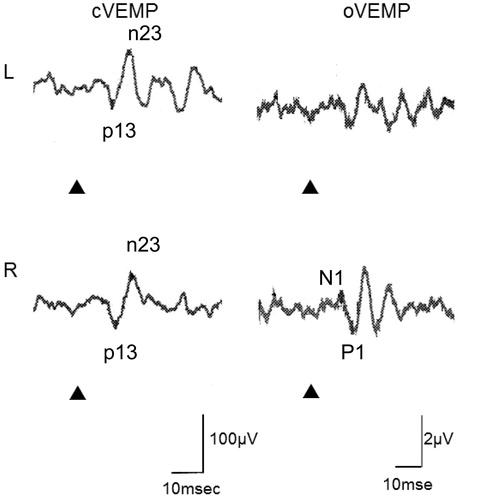

He visited our clinic with complaints of a tilting sensation of the room. This sensation lasted only a few minutes. He felt nauseous during episodes. He also had headache, but it was mild. He did not have cochlear symptoms or loss of consciousness. His mother had migraine. On examination, he had normal equilibrium and normal hearing with normal tympanic membranes on visual inspection. Qualitative head impulse test [Citation8] was normal. He showed normal cVEMP on both sides, but oVEMP responses to the left ear stimulation were absent (Figure ). VEMPs were recorded using Neuropack system (Nihon Kohden Co. Ltd.). Electrodes were placed on the mid-portion of the SCM (active) and the lateral end of the upper sternum (reference) for cVEMP and on the just below the lower eye lid (active) and 2 cm below the active electrode (reference). He was asked to raise his head from the supine position during cVEMP recording (500 Hz short tone bursts, rise/fall time = 1 ms, plateau time = 2 ms, 125dBSPL, air-conducted) while he was asked to keep upward gaze (20 deg) during oVEMP recording (500 Hz short tone bursts, rise/fall time = 1 ms, plateau time = 2 ms, 125dBSPL, air-conducted). He did not have any other abnormal neurological findings. His brain CT was normal. Although his medical history sounded benign paroxysmal vertigo (of childhood) (BPV),[Citation9] he was not diagnosed with BPV because his sensation was not typical rotatory vertigo and he showed abnormal VEMP during the symptom-free period. He was diagnosed with IOV type 1.[Citation3,Citation4]

Patient #2 (a 15-year-old girl)

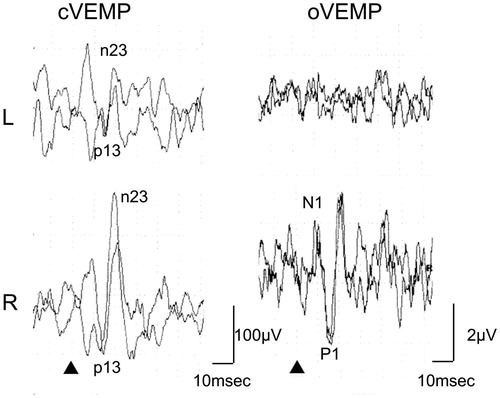

She visited our clinic with complaints of episodic sensations of lateral tilting lasting several hours. She did not have cochlear symptoms. She sometimes had headache, but it did not occur simultaneously with her tilting sensation. On examination, she had normal equilibrium and normal hearing with normal tympanic membranes on visual inspection. Caloric test was normal on both sides. She showed a tendency of decreased cVEMP on the left, (asymmetry ratio = 37.3 by corrected amplitudes), but it was still within the normal limit according to our current criteria based on the data of healthy adults.[Citation10] She did not show oVEMP responses to left ear stimulation (Figure ). Recording methods of VEMPs were the same as Patient #1. She did not have any other abnormal neurological findings. Her brain CT was normal. She was not diagnosed with BPV because her sensation was not typical vertigo and she showed abnormal VEMP during the symptom-free period. She was not diagnosed with vestibular migraine (VM) because she did not have migraineous headache with her vestibular symptom. She was not diagnosed with Meniere’s disease because she did not have hearing loss. She was diagnosed with IOV type 1.[Citation3]

Figure 2. VEMP responses of Patient #2. She showed tendency of decreased amplitudes of cVEMP on the left, however, asymmetry ratio (AR) of corrected amplitudes (=37.4) did not reach the upper limit of the normal range according to our criteria (=41.6 [Citation8]). She showed absence of oVEMP responses to the left ear stimulation. Stimuli were 500 Hz air-conducted short tone bursts (125 dBSPL) ▴: STB presentation.

![Figure 2. VEMP responses of Patient #2. She showed tendency of decreased amplitudes of cVEMP on the left, however, asymmetry ratio (AR) of corrected amplitudes (=37.4) did not reach the upper limit of the normal range according to our criteria (=41.6 [Citation8]). She showed absence of oVEMP responses to the left ear stimulation. Stimuli were 500 Hz air-conducted short tone bursts (125 dBSPL) ▴: STB presentation.](/cms/asset/7fedb9e1-51a4-419c-ac97-452eb43bb13c/icro_a_1235466_f0002_b.jpg)

Patient #3 (an 8-year-old boy)

He visited our clinic with complaints of episodes of pulling sensation to the left. This sensation was brief. He felt nauseous during episodes. He did not have headache. He did not have cochlear symptoms. His father had migraine. On examination, he had normal equilibrium and normal hearing with normal tympanic membranes on visual inspection. Qualitative head impulse test was normal. He showed decreased cVEMP amplitudes to the left side stimulation and absence of oVEMP to the left side stimulation (Figure ). Recording methods of VEMPs were the same as Patient #1. He did not have any other abnormal neurological findings. His brain MR imaging was normal. He was not diagnosed with BPV because his sensation was not typical vertigo and was too short. Furthermore, he showed abnormal VEMP during the symptom-free period. He was diagnosed with IOV type 1.[Citation3]

Discussion

All 3 patients in this report complained of tilting or translation sensation in the roll plane. Their symptoms seemed to be caused by dysfunction of the utricle, one of the otolith organs.[Citation1] All 3 patients showed unilateral abnormal oVEMP responses, while they had normal or decreased cVEMP responses on the same side (Table ). Their common findings concerning VEMP indicated unilateral utricular dysfunction, because oVEMP predominantly reflects utricular function.[Citation4,Citation10] Clinicians should be careful for assessment of the condition of the middle ear in pediatric cases because children frequently have middle ear problems such as otitis media with effusion, although patients in this report did not show middle ear problems. However, it may be difficult to exclude completely the possibility of small conductive problems as a cause of absence of VEMPs.

Table 1. Summary of patients.

Murofushi et al. have proposed diagnostic criteria of IOV as follows,[Citation3,Citation4] although IOV needs further discussion to be established as a new clinical entity.

Inclusion criteria

Subjects with any of the following were included:

Episodic lateral tilting or translational sensations (type 1).

Episodic anteroposterior tilting or translational sensations (type 2).

Episodic up-down translational sensations (type 3).

Exclusion criteria

Subjects with any of the following were excluded:

A medical history of rotatory vertigo.

A medical history of loss of consciousness or severe head trauma.

Symptoms of central nervous system dysfunction or proprioceptive dysfunction.

A definitive diagnosis of a disease known to cause disequilibrium and/or vertigo (e.g. Meniere’s disease, vestibular migraine, etc.).

Patients in this report fulfilled these criteria. All of them were classified into type 1.

While patients in this report shared common features of IOV with adult patients,[Citation1–3] they showed some different tendency. Different from adult patients, duration of episodes in children tended to be shorter than adults,[Citation1–3] and children with IOV suggested some association with migraine.

They cannot be diagnosed with BPV or vestibular migraine, although they suggested association with migraine. Patients #1 and #3 had family histories of migraine, however, duration of their symptoms was short (shorter than 5 min.). All patients showed abnormal vestibular tests (VEMP) during the symptom-free period. According to the diagnostic criteria of BPV in ICHD3β (international classification of headache disorders version 3 beta), patients with BPV must not have auditory or vestibular signs/symptoms during symptom-free periods.[Citation9] Patient #2 had migraineous headache, however, her vestibular symptoms were not synchronized with other migraineous symptoms. Therefore, she cannot be diagnosed with vestibular migraine, either.[Citation9,Citation11]

However, the medical history of these 3 patients seems to have some association with migraine. Therefore, IOV in children may share common pathophysiology with BPV and/or VM, in other words, migraine. The previous studies have reported that BPV is one of the most common causes of vertigo in children.[Citation12,Citation13] BPV is considered to be a migraine precursor,[Citation14,Citation15] and its prevalence is estimated to be 2.6%.[Citation16]

In the previous study in adults, Murofushi et al. suggested that IOV patients with relatively long attacks could have otolithic endolymphatic hydrops.[Citation3] In the study, they stated that pathophysiology with short attacks were remained to be clarified. The present report provides information that the pathophysiology of IOV with short attacks may have similar pathophysiology to BPV and/or VM.

What is the pathophysiology of BPV and VM? Murofushi proposed six possible pathophysiology of VM: (1) ischemia due to vasospasm, (2) neural dysfunction such as spreading depression, (3) effects of released neuropeptides and/or neurogenic inflammation, (4) secondary endolymphatic hydrops to (3), (5) lowering of sensation thresholds due to sensitization, and (6) ion-channel disorders such as in familial hemiplegic migraine.[Citation4,Citation17] Among these possible pathophysiologies, ischemia due to vasospasm may match with short IOV attacks, and this might be the pathophysiology of IOV in children. This hypothesis may also be applicable to IOV in adults with short duration of attacks.

Disclosure statement

The authors do not have any conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Murofushi T, Nakahara H, Yoshimura E. Assessment of the otolith-ocular reflex using ocular vestibular evoked myogenic potentials in patients with episodic lateral tilt sensation. Neurosci Lett. 2012;515:103–106.

- Murofushi T, Komiyama S, Yoshimura E. Do patients who experience episodic tilting or translational sensations in the pitch plane have abnormal sacculo-collic reflexes?. Neurosci Lett. 2013;553:95–98.

- Murofushi T, Komiyama S, Hayashi Y, et al. Frequency preference in cervical vestibular evoked myogenic potential of idiopathic otolithic vertigo patients. Does it reflect otolithic endolymphatic hydrops? Acta Otolaryngol. 2015;135:995–999.

- Murofushi T. Clinical application of vestibular evoked myogenic potential (VEMP). Auris Nasus Larynx. 2016;43:367–376.

- Seo T, Node M, Miyamoto A, et al. Three cases of cochleosaccular endolymphatic hydrops without vertigo revealed by furosemide-loading vestibular evoked myogenic potential test. Otol Neurotol. 2003;24:807–811.

- Curthoys IS, Manzari L. Otolithic disease: clinical features and the role of vestibular evoked myogenic potentials. Semin Neurol. 2013;33:231–237.

- Brandt T. Otolithic vertigo. Adv Otorhinolaryngol. 2001;58:34–47.

- Halmagyi GM, Curthoys IS. A clinical sign of canal paresis. Arch Neurol. 1988;45:737–739.

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The international classification of headache disorders. 3rd ed (beta version). Cephalalgia. 2013;33:629–808.

- Murofushi T, Nakahara H, Yoshimura E, et al. Association of air-conducted sound oVEMP findings with cVEMP and caloric test findings in patients with unilateral peripheral vestibular disorders. Acta Otolaryngol. 2011;131:945–950.

- Lempert T, Olesen J, Furman J, et al. Vestibular migraine: diagnostic criteria. J Vestib Res. 2012;22:167–172.

- Jahn K. Vertigo and balance in children-diagnostic approach and insights from imaging. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2011;15:289–294.

- Bower CM, Cotton RT. The spectrum of vertigo in children. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1995;121:911–915.

- Lagman-Bartolome AM, Lay C. Pediatric migraine variants: a review of epidemiology, diagnosis, treatment, and outcome. Neurol Neurosci Rep 2015;15:34. doi: 10.1007/s11910-015-0551-3.

- Drigo P, Carli G, Maria Laverda AM. Benign paroxysmal vertigo of childhood. Brain Dev 2001;23:38–41.

- Abu-Arafeh I, Russell G. Paroxysmal vertigo as a migraine equivalent in children: a population-based study. Cephalalgia 1995;15:22–125.

- Murofushi T. Migraine-associated vertigo (in Japanese). Equilibrium Res 2011;70:172–175.