Abstract

We report on a previously healthy 11-year-old male presenting with meningoencephalitis and otitis media. Computed tomography demonstrated opacification of the right middle ear and mastoid ear cells, but no destructive changes. Anti-Mycoplasma pneumoniae IgG and IgM were positive in serum and at high concentrations in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and its nucleic acid was detected in the middle ear fluid and in a throat swab, but not in CSF. EEG showed generalized slowing and right temporal sharp waves. Brain MRI imaging remained normal. After a 3-week treatment with doxycycline and a tympanostomy tube, the patient recovered, and no long-term neurological sequelae have appeared. Diagnostics and pathogenetic mechanisms in meningoencephalitis caused by M. pneumoniae are discussed.

Introduction

Mycoplasma pneumoniae (Mp) causes common respiratory tract infections. Neurological symptoms are seen in about 1–12% of the patients hospitalized for Mp infection.[Citation1,Citation2] In children, encephalitis is the most frequent extrapulmonary manifestation. About 10–17% of acute childhood encephalitis in Europe and North America are caused by Mp.[Citation3,Citation4] Other less frequent neurological manifestations include acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, transverse myelitis, polyradiculitis, cerebellar ataxia, meningitis and stroke.[Citation1,Citation2]

In the northern hemisphere Mp infections have increasingly been reported in outbreaks.[Citation5–7] A central nervous system (CNS) invasion by Mp is diagnosed based on serology, culture or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) from the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and after excluding other causes.[Citation8,Citation9] Up to one-third of patients with Mp infection may have ear infection, but PCR has been positive from middle ear fluid in rare cases.[Citation5,Citation10,Citation11] The CNS manifestations of Mp infections are known to arise from different pathogenetic pathways with and without direct invasion of the pathogen into the CSF.[Citation1,Citation2,Citation9]

Case report

An 11-year-old boy had a history of atopic eczema and allergic rhinitis. Due to secretory otitis media, ventilation tubes were installed in both tympanic membranes in November 2010, after which his ears healed and hearing recovered. He had no history of neurological or cognitive concerns, except for mild difficulties in mathematics at school. The boy was referred to our hospital on 29 September 2014 due to 11 days of cough, headache and a fever of up to 39.4 °C. He had had a 5-day course of oral cefalexin with no relief of his symptoms. The main symptoms, clinical findings, laboratory and imaging results and therapeutic interventions are summarized in Table .

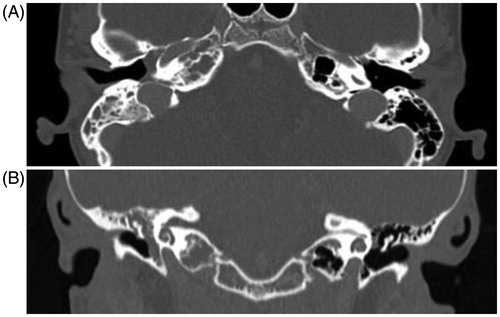

Figure 1. Computed tomography. (a). Horizontal section. (b). Coronal section. Opacification of the right middle ear and the temporal bone air cell system, including the mastoid and pars petrosal, but no destruction of the bony septa.

Table 1. Clinical history and outcome of the patient in chronological order.

Discussion

Our patient presented with respiratory symptoms, otitis media, and meningoencephalitis caused by Mp. A respiratory tract infection with Mp was confirmed by positive PCR from a throat swab as well as from the middle ear fluid and positive serology. The diagnosis of Mp meningoencephalitis was based on the clinical picture, CSF findings, EEG, and antibody detection in the CSF and serum. CSF contained a higher IgG titer than serum, and CSF IgM was also positive, a finding indicative of endogenous intrathecal antibody production.

Acute childhood encephalitis is a potentially fatal disease,[Citation9] but a Californian study found that Mp-associated encephalitis, compared to other etiologies, caused less-severe hospital courses.[Citation12] Other studies, however, have reported long-term neurologic sequelae in about half of the patients.[Citation1,Citation3] The absence of any brain MRI abnormalities and seizures during the disease course may have been indicators for better prognosis in case of our patient.

The CSF findings of our patient were similar to those described in the literature: mild-to-moderate pleocytosis with a predominance of lymphocytes, slightly elevated protein concentrations, and normal glucose levels.[Citation3,Citation9,Citation12] Like our patient, more than half of the patients reportedly had an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate.[Citation3] The diagnosis is challenging and should not rely on a single test. Mp infections are common, and diagnostic methods have their limitations.[Citation4,Citation5,Citation12] Serologic testing can yield positive results several months after an infection, or even false negative results.[Citation3,Citation5,Citation12] Cultures lack sensitivity. PCR is the most sensitive test, especially in the early stage of the disease, but different assays perform variably.[Citation3,Citation9,Citation12] Recent studies have also shown that asymptomatic carriage of Mp in the upper respiratory tract is common in children.[Citation5,Citation13]

EEG is often abnormal with diffuse slowing, as in our patient; focal abnormalities are less common.[Citation3,Citation12] Brain MRI shows abnormalities in about half of the patients, mainly focal ischaemia or edema, or increased signal intensities.[Citation1,Citation3,Citation12]

In previous reports, only about half of the children with Mp encephalitis experienced respiratory symptoms.[Citation3,Citation12] In our patient, Mp was detected in a pharyngeal swab and in middle ear fluid. To our knowledge, rare cases of otitis have shown Mp in the middle ear fluid,[Citation10,Citation11] but no case with concomitant meningoencephalitis has been described before. Italian researchers did, however, publish a case report on a child with meningitis following acute otitis media and positive Mp serology 25 years ago.[Citation14] In most cases, the respiratory tract is considered the likely entry point.[Citation3,Citation12] Our patient’s meningoencephalitis could have been otogenic. However, the long prodrome of respiratory signs and fever before the neurological symptoms suggests the possibility of an immunologically mediated pathogenetic mechanism.

A recent study of neurological complications of PCR-proven Mp infections in children observed two distinct patterns of encephalitis: (1) no or short (<7 days) prodrome, less frequent respiratory manifestations and detection of Mp by PCR in the CSF (in 75%) but not in respiratory tract, and (2) a prolonged prodrome (>7 days), respiratory manifestations, and detection of Mp in the respiratory tract but not in CSF. They speculated the presence of an immunologically mediated disease mechanism in the latter group, and direct invasion of CNS by the bacteria in the former.[Citation1]

Treatment targets the mechanism of the disease. Intravenous immunoglobulin and steroids have been administered on suspicion of autoimmune mechanisms in Mp encephalitis.[Citation3,Citation5,Citation12] No controlled clinical trials on antimicrobial therapy in Mp encephalitis exist, but antibiotic therapy has in some cases – including ours – temporally associated with improvement.[Citation3] An antibiotic such as azithromycin, doxycycline, or a fluoroquinolone should be used, because of their antimycoplasmal activity and their ability to traverse the blood–brain barrier.[Citation3,Citation9,Citation12] Fluoroquinolones can be used in children to treat severe infections. Doxycycline can be used in children over 8 years of age. An oral permission to publish this case report was obtained from the parents.

Notes on contributor

Participated in patient treatment (TP, AS, TR, STS, JJ), participated in preparing the manuscript (TP, AS, TR, STS, JJ).

Disclosure statement

None of the authors has conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

References

- Al-Zaidy SA, MacGregor D, Mahant S, et al. Neurological complications of PCR-proven infections in children: prodromal illness duration may reflect pathogenetic mechanism. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61:1092–1098.

- Tsiodras S, Kelesidis I, Kelesidis T, et al. Central nervous system manifestations of Mycoplasma pneumonia infections. J Infect. 2005;51:434–454.

- Bitnun A, Ford-Jones EL, Petric M, et al. Acute childhood encephalitis and Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:1674–1684.

- Domenech C, Leveque N, Lina B, et al. Role of Mycoplasma pneumoniae in pediatric encephalitis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2009;28:91–94.

- Waites KB, Talkington DF. Mycoplasma pneumoniae and its role as a human pathogen. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17:697–728.

- Eibach D, Casalegno JS, Escuret V, et al. Increased detection of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in children, Lyon, France, 2010 to 2011. Euro Surveill. 2012;17:20094.

- Walter ND, Grant GB, Bandy U, et al. Community outbreak of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection: school-based cluster of neurologic disease associated with household transmission of respiratory illness. J Infect Dis. 2008;198:1365–1374.

- Bencina D, Dovc P, Mueller-Premru M, et al. Intrathecal synthesis of specific antibodies in patients with invasion of the central nervous system by Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2000;19:521–530.

- Daxboeck F, Blacky A, Seidl R, et al. Diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of Mycoplasma pneumoniae childhood encephalitis: systematic review of 58 cases. J Child Neurol. 2004;19:865–871.

- Raty R, Kleemola M. Detection of Mycoplasma pneumoniae by polymerase chain reaction in middle ear fluids from infants with acute otitis media. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000;19:666–668.

- Storgaard M, Tarp B, Ovesen T, et al. The occurrence of Chlamydia pneumoniae, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, and herpesviruses in otitis media with effusion. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2004;48:97–99.

- Christie LJ, Honarmand S, Talkington DF, et al. Pediatric encephalitis: what is the role of Mycoplasma pneumoniae?. Pediatrics. 2007;120:305–313.

- Spuesens EB, Fraaij PL, Visser EG, et al. Carriage of Mycoplasma pneumoniae in the upper respiratory tract of symptomatic and asymptomatic children: an observational study. PLoS Med. 2013;10: e1001444.

- Bruni L, Comparcola D, Ferrante E, et al. Neurological complications of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. Description of a case of meningitis with clear cerebrospinal fluid. Pediatr Med Chir. 1990;12:271–273.