Abstract

When performing thyroplasty, local anesthesia is better to check patient’s voice. However, some cases need general anesthesia for various reasons. To evaluate limitations of arytenoid adduction (AA) under general anesthesia. We report five cases of AA performed under general anesthesia. Four cases were treated AA only and one case was performed nerve-muscle pedicle implantation with AA. Voice was evaluated by maximum phonation time (MPT), mean air flow rate (MFR), and auditory impression using four score levels (0–3) for grade (G), roughness (R) and breathiness (B). Improvements in MPT and MFR were seen all patients. However, glottal gap remained post-surgery with G (1) voice in four AA alone patients. Another patient who underwent AA with nerve-muscle pedicle implantation achieved excellent voice with G (0). AA under general anesthesia improve patient’s voice but sometimes insufficient. Combined treatment with nerve-muscle implantation should be considered.

Introduction

For unilateral vocal fold paralysis, we consider arytenoid adduction (AA) surgery under local anesthesia the procedure of choice. In general, position of paralyzed vocal fold divided into paramedian or intermedian. It is also said paralyzed vocal fold having large posterior glottal chink tend to have severe level difference during phonation. However according to our research over 10 years, passive movement of the paralyzed vocal fold, with displacement outward and upward, is present in all cases of unilateral vocal fold paralysis on phonation [Citation1–3], and AA is essential for achieving a good voice [Citation3,Citation4]. During surgery, simulation is carried out while listening to the patient’s voice and concurrently performing type 1 or 4 thyroplasty. We have conducted AA surgery under local anesthesia for almost 300 patients at Tokyo Medical University Hospital and associated hospitals. The result has been 100% improvement in the voice of most patients, with a maximum phonation time (MPT) of 10 s or greater and mean air flow rate (MFR) of 200 ml or less [Citation4,Citation5]. Voice improvement does not depend on the severity of preoperative phonetic impairment (e.g. MPT will improve to 30 s or more even in patients with an MPT of 1 s). In addition, ∼60% of patients have said that they were able to sing after the operation [Citation6]. To our knowledge, this is one of the best reported outcomes for vocal cord paralysis surgery. The results reflect the fact that AA, a procedure to restore physiological adduction of the vocal cords, and type 1 thyroplasty, a procedure to restore the volume of the paralyzed thyroarytenoid muscle, are performed under local anesthesia while listening to the patient’s voice. However, for various reasons, AA is occasionally performed under general anesthesia. If AA was performed under general anesthesia, it would not be possible to make adjustments while listening to the patient’s voice, making a satisfactory surgical outcome unlikely. The inability to perform voice monitoring means that post-operative vocal improvements may be moderate. The aim of this report is to evaluate effect and limitation of AA surgery under general anesthesia.

Materials and methods

Patient

The subjects were five patients (one male and four females) who underwent surgery for unilateral vocal fold paralysis (UVFP) between April 2015 and June 2017 in our department. Their mean age was 62 years (range, 37–77 years). The paralysis resulted from thyroid surgery in three patients, cerebellopontine angle tumor surgery in one patient, and ascending aortic aneurysm replacement surgery in one patient. The patient who had undergone ascending aortic aneurysm surgery had been heparinized, so a strong bleeding tendency was present. General anesthesia was used in these patients because two patients had refused local anesthesia because of anxiety, local anesthesia was not possible in one patient because of panic disorder, and general anesthesia was used for the patient with a strong bleeding tendency because minimally invasive surgery was required. In the remaining patient, in whom Gore-Tex® had been inserted up to the posterior area during type 1 thyroplasty at another hospital, the fenestration approach was begun under local anesthesia but then abandoned due to scarring around the arytenoid cartilage.

Voice evaluation

A voice evaluation was conducted based on the MPT, MFR, and auditory impression. MPT was measured according to Japan Society of Logopedics and Phoniatrics guidelines. MPT were recorded three times before and after surgery using a sustained vowel (/a/) at a comfortable pitch. The longest data was used as result. We also measured the mean flow rate (MFR) of each patient. The MFR in the most comfortable condition was measured using a phonation analyzer (PS-77; Nagashima, Tokyo, Japan). The patient’s voice was evaluated as “improved” if the MPT was ≥ 10 s and “moderate” if it was < 10 s. Auditory impression was evaluated by three doctors according to degree of hoarseness using four score levels (0–3) on the grade, roughness, breathiness (GRB) scale. Glottal closure was evaluated by stroboscopy after surgery. The cases did not have complete closure were judged as Insufficient closure.

Surgical procedure

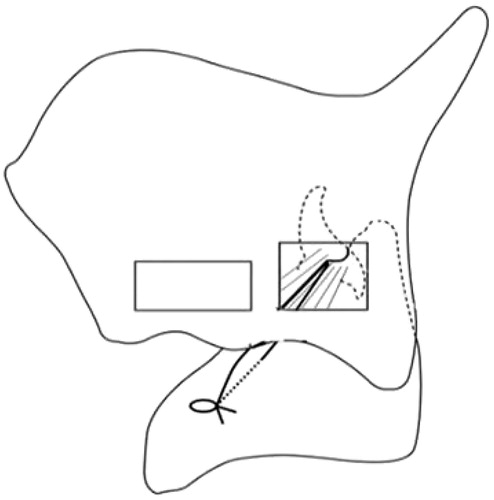

We treated five UVFP cases under general anesthesia. In three of them, AA was conducted using endoscopic-assisted AA surgery (EAAS) by Murata [Citation7] (Figure ), and only AA was performed. In the remaining two cases, AA was performed using a fenestration approach (Figure ). In one case, this was combined with nerve-muscle pedicle implantation using the ansa cervicalis onto the vocal fold muscle. In the other case, only AA was conducted because good nerve-muscle pedicle implantation was unobtainable due to previous thyroid surgery.

Figure 1. Endoscopic-assisted arytenoid adduction surgery (EAAS). From the cricothyroid ligament toward the piriform sinus, the penetration needle and the loop needle are inserted, and the retracted nylon threads are tightened with a spacer at the cricothyroid ligament. The arytenoid cartilage is successfully adducted. This figure is modified from Murata et al. [Citation7].

![Figure 1. Endoscopic-assisted arytenoid adduction surgery (EAAS). From the cricothyroid ligament toward the piriform sinus, the penetration needle and the loop needle are inserted, and the retracted nylon threads are tightened with a spacer at the cricothyroid ligament. The arytenoid cartilage is successfully adducted. This figure is modified from Murata et al. [Citation7].](/cms/asset/ac0f36f0-fa37-43ca-8065-0efd1da6968f/icro_a_1655429_f0001_b.jpg)

Reasons of general anesthesia

General anesthesia was selected in four patients because of their severe anxiety concerning local anesthesia, with a history of panic-like episodes in one patient. In the remaining one patient, AA was performed at our hospital under local anesthesia as additional surgery to type 1 thyroplasty at another hospital. However, we could not reach the arytenoid cartilage because of scarring resulting from the type 1 surgery and therefore performed the surgery according to EAAS.

Results

Four cases of AA alone

Improvements in MPT and MFR were identified in all four cases. Four patients who underwent either the fenestration approach alone or EAAS alone. The increase in MPT (post-surgery mean MPT/pre-surgery mean MPT) was 285% (14.25 s/5 s). Improvement in MFR was seen in all patients, to ≤ 250 ml/s. However, glottal closure failure remained post-surgery in three of the four patients. Result of GRB score is listed in Table .

Table 1. Pre- and post-operative results.

A case of AA with nerve-muscle pedicle implantation

In the patient who underwent fenestration AA with nerve-muscle pedicle implantation, the MPT was greatly prolonged from 2 s to 17 s, and the MFR was markedly improved from 1373 ml/s to 126 ml/s, achieving satisfactory voice quality. Improvement in glottal closure failure was also seen in that patient. The post-operative auditory impression evaluation was G (0), R (0) B (0).

Discussion

In unilateral vocal fold paralysis, the arytenoid cartilage on the affected side is displaced outward and upward on phonation. Neurophysiologically, the arytenoid cartilage is unstable on the cricoid cartilage in patients with complete paralysis, so passive movement of the arytenoid cartilage is observed on inspiration for phonation. A certain amount of muscle contraction capacity remains in cases of incomplete paralysis, as adduction motion is stronger on the unaffected side. The affected side is displaced outward and upward in passive movement even in cases of incomplete paralysis [Citation1,Citation2].

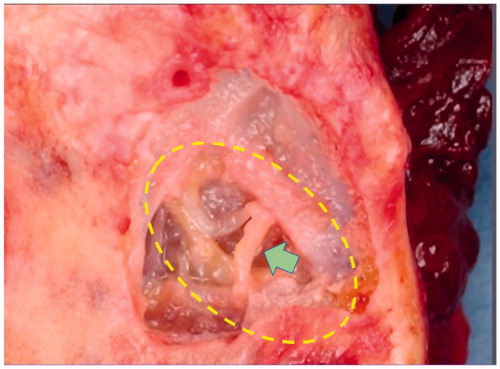

Among the surgical procedures that may be considered, the only one able to remedy the passive movement of the arytenoid cartilage on the affected side is AA. As the arytenoid cartilage will be fixed in the adducted position, strong resistance at exhalation may be obtained by regaining a two-point supporting structure using the vocal folds as if they were musical instrument strings [Citation3]. For this reason, we consider AA to be the procedure of first choice in all cases of vocal fold paralysis, regardless of the degrees of phonetic and neurophysiological severity. When the procedure is performed under local anesthesia, the volume of the atrophied vocal fold muscle may be augmented in serious cases by including type 1 thyroplasty or other medialization procedures. In such cases, monitoring of the patient’s voice during surgery is essential. The voice was improved in all cases treated at our hospital, with no cases being unchanged or worsened. The fenestration approach involves approaching the arytenoid cartilage through a small window made in the thyroid cartilage (Figure ) [Citation4], and the development of an approach from the larynx side allowed us to simplify the procedure. A feature of this procedure is that physiological adduction of the arytenoid cartilage is sure to be restored because sutures may be pulled in the direction of contraction of the lateral cricoarytenoid muscle. In this report, we used this technique for AA under general anesthesia.

Murata et al. [Citation7] have recently been using EAAS. This is a new, minimally invasive arytenoid cartilage procedure in which, while observing the laryngeal cavity with the endoscope, an injection needle inserted through the neck is used to attach a suture to the muscular process (Figure ). Isshiki et al. [Citation8] reported a procedure that achieved adduction of the arytenoid cartilage muscular process in 1978, but that procedure was highly invasive and carried a risk of post-operative hemorrhage and difficulty breathing due to laryngeal edema. This was because of the need to resect part of the thyroid cartilage and surgical procedures in the vicinity of the arytenoid cartilage and hypopharynx pyriform sinus mucosa. According to previous studies, tracheostomy was conducted post-operatively at a frequency of 2–5% to secure an airway [Citation9,Citation10]. EAAS involves no exposure of the muscular process, and the range of surgical procedures is smaller than with previous adduction surgeries, so there is little possibility of post-operative hemorrhage or airway constriction due to laryngeal edema. Also, adduction of the muscular process can be performed under observation by laryngoscopy, potentially allowing voice-improving effects in no way inferior to those of existing adduction surgery techniques.

In the present study, the performance under general anesthesia of fenestration alone or EAAS alone achieved good post-operative results in terms of MPT and MFR, but glottal closure failure remained in three of four patients (Table ). However, combining type 1 thyroplasty with such adduction surgery would be effective in restoring the volume of the atrophied vocal cord on the paralyzed side and therefore might have improved the glottal closure failure.

In this regard, we previously conducted a study on the combination of type 1 thyroplasty with arytenoid cartilage adduction under general anesthesia in two patients using a laryngeal mask [Citation11]. In one patient, dyspnea appeared post-operatively. Endoscopy revealed the cause as overcorrection due to the Gore-Tex® used in type 1 thyroplasty, which therefore had to be removed. Another study described type 1 thyroplasty conducted together with AA by EAAS under general anesthesia, comparing three subjects who underwent adduction alone and three subjects who underwent adduction together with thyroplasty [Citation7]. The combination of adduction and thyroplasty was found to further improve the MPT and MFR [Citation7].

Unlike with local anesthesia, the voice cannot be monitored during surgery under general anesthesia. As over- or under-correction can occur with type 1 thyroplasty, we do not currently use this procedure in AA under general anesthesia. Whether type 1 thyroplasty should be used concurrently in such cases remains controversial.

The combination of nerve-muscle flap placement with fenestration in one patient in the present study achieved a very good outcome. Improvement was seen in both MPT and MFR, with the former increasing from 2 s to 17 s and the latter decreasing from 1373 ml/s to 126 ml/s. In addition, the glottal closure failure seen with AA alone was absent, representing another clear improvement.

To ensure improved phonation with surgery for unilateral vocal fold paralysis, the position of the paralyzed vocal fold must be fixed in the median position and the volume of the contracted vocal fold must be reproduced. AA is needed to move the vocal fold to the midpoint to reproduce natural adduction, and type 1 thyroplasty and nerve-muscle flap placement are needed to reproduce the vocal fold volume.

When using general anesthesia, nerve-muscle flap placement would be very useful for the reasons mentioned above. In a study by Tucker et al. [Citation12], improvement in the voice of patients with laryngeal paralysis was achieved by grafting a nerve-muscle flap onto the vocal cord muscle, obtaining the flap from the ansa cervicalis and omohyoid muscle. In addition, May et al. [Citation13] obtained improvements in the voice by grafting a nerve-muscle flap onto the lateral cricoarytenoid muscle. Furthermore, Yumoto et al. used a nerve-muscle flap made from the sternohyoid muscle and a nerve thicker than the ansa cervicalis, and employed a nerve-stimulating device during surgery. They found that placement of the flap after confirming adequate activity using the device achieved very good outcomes [Citation14–16]. In neck dissection patients, when a nerve-muscle flap cannot be obtained from the affected side, a flap can usually be taken from the unaffected side. However, in rare cases, a flap may not be obtainable from bilateral neck surgery patients because of tumor invasion or other reasons.

In the present study, the combination of AA and nerve-muscle flap placement was considered effective for improving the voice in unilateral vocal fold paralysis patients.

One advantage of endoscopic-assisted adduction surgery is that it only requires the insertion of needles, and separation of tissue is generally unnecessary. For patients in whom surgical procedures are difficult because of scarring after neck surgery, local anesthesia may not work particularly well. Also, in patients with a high risk of post-operative hemorrhage, endoscopic-assisted surgery will obviously reduce such risk because little separation of tissue is involved. In addition, if the invasiveness of surgery must be minimized for any reason, AA by EAAS would probably be less invasive than fenestration. However, care must be taken to avoid damaging the blood vessels of the lateral cricoarytenoid muscle accompanying the adduction branch of the recurrent laryngeal nerve, outside the lateral cricoarytenoid muscle (Figure ). Adjustment of type 1 thyroplasty might be difficult if adduction surgery is performed under general anesthesia. As mentioned before, over collection of type 1 thyroplasty may become patient voice worse than before surgery and dyspnea may appeared after surgery. On the other hand, hoarseness may remain without type 1 thyroplasty. It is difficult to say that type 1 thyroplasty should be performed with AA under general anesthesia or not. To achieve even better voice quality, combined treatment with nerve-muscle pedicle implantation should be considered because the result is good and less air way complication. However there are some patients who can not perform nerve-muscle pedicle implantation.

Conclusion

AA under general anesthesia improve patient’s voice but sometimes insufficient. Combined treatment with nerve-muscle implantation should be considered.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Hiramatsu H, Tokashiki R, Suzuki M. Usefulness of three-dimensional computed tomography of the larynx for evaluation of unilateral vocal fold paralysis before and after treatment: technique and clinical applications. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2008;265:725–730.

- Hiramatsu H, Tokashiki R, Nakamura M, et al. Characterization of arytenoid vertical displacement in unilateral vocal fold paralysis by three-dimensional computed tomography. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;266:97–104.

- Tokashiki R, Hiramatsu H, Tsukahara K, et al. Direct pull of lateral cricoarytenoid muscle for unilateral vocal cord paralysis. Acta Otolaryngol. 2005;125:753–758.

- Tokashiki R, Hiramatsu H, Tsukahara K, et al. A “fenestration approach” for arytenoid adduction through the thyroid ala combined with type 1 thyroplasty. Laryngoscope. 2007;117:1882–1887.

- Motohashi R, Tokashiki R, Hiramatsu H, et al. A fenestration approach to arytenoid adduction for unilateral vocal cord paralysis –results of 32 cases. Nihon Kikan Shokudoka Gakkai Kaiho. 2009;60:1–7. Japanese

- Tokashiki R, Hiramatsu H, Shinada E, et al. Analysis of pitch range after arytenoid adduction by fenestration approach combined with type I thyroplasty for unilateral vocal fold paralysis. J Voice. 2012;26:792–796.

- Murata T, Yasuoka Y, Shimada T, et al. A new and less invasive procedure for arytenoid adduction surgery: endoscopic-assisted arytenoid adduction surgery. Laryngoscope. 2011;121:1274–1280.

- Isshiki N, Tanabe M, Sawada M. Arytenoid adduction for unilateral vocal cord paralysis. Arch Otolaryngol. 1978;104:555–558.

- Abraham MT, Gonen M, Kraus DH. Complications of type I thyroplasty and arytenoid adduction. Laryngoscope. 2001;111:1322–1329.

- Weinman EC, Maragos NE. Airway compromise in thyroplasty surgery. Laryngoscope. 2000;110:1082–1085.

- Kanebayashi H, Tokashiki R, Hiramatsu H, et al. Two cases of laryngoplasty performed under a general anesthesia applied using a laryngeal mask for the treatment of unilateral vocal cord paralysis. Nippon Jibiinkoka Gakkai Kaiho (Tokyo). 2006;109:655–659. Japanese

- Tucker HM. Reinnervation of the unilaterally paralyzed larynx. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1977;85:789–794.

- May M, Beery Q. Muscle-nerve pedicle laryngeal reinnervation. Laryngoscope. 1986;96:1196–1200.

- Kumai Y, Ito T, Udaka N, et al. Effects of a nerve-muscle pedicle on the denervated rat thyroarytenoid muscle. Laryngoscope. . 2006;116:1027–1032.

- Miyamaru S, Kumai Y, Minoda R, et al. Nerve-muscle pedicle implantation in the denervated thyroarytenoid muscle of aged rats. Acta Otolaryngol. 2012;132:210–217.

- Yumoto E, Sanuki T, Toya Y, et al. Nerve-muscle pedicle flap implantation combined with arytenoid adduction. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;136:965–969.