Abstract

Introduction

Hemangiomas are benign vascular lesions. The complicated hemangiomas that are causing significant functional or cosmetic problems need surgical excision. This paper presents a novel technique of reconstruction using surgical mesh after removal of a facial hemangioma.

Case report

A 50-year-old male patient presented with right cheek swelling for more than 40 years causing disproportion of the face. A flap was raised by a nasolabial linear incision, then a 4*2 cm surgical mesh was put in, and the wound closed cosmetically. The excised tissue was sent for histopathological examinations and the results confirmed hemangioma. After more than two years follow up, the patient’s face was symmetrical with normal facial contour.

Conclusion

The application of surgical mesh for patients who seek functional and cosmetic improvements after hemangioma removal is a constructive method that gives the desired outcome for the patient.

Introduction

Hemangiomas (HGMs) are benign vascular lesions categorized as capillary or cavernous HGMs. Capillary HGMs are characterized by densely arranged blood vessels and predominantly manifest on cutaneous, subcutaneous, mucosal, and labial surfaces, with occasional occurrences in visceral organs such as the liver, kidneys, and spleen. Conversely, although less prevalent, cavernous HGMs exhibit larger, more indistinct vascular spaces, often situated at greater depths compared to their capillary counterparts [Citation1,Citation2] [beningn tumour neoplasm][Citation3]. Another classification of this benign neoplasm is congenital and infantile HGMs. Congenital HGMs are rare and vague, while infantile hemangiomas (IHs) are regarded as the most common tumors arising during childhood. IHs have nearly 5-10% occurrence in total population. They occur most frequently in the head and neck area in about 60% of cases [Citation4–7]. The known risk factors are white ethnicity, low birth weight, female gender, chorionic villus sampling, being premature, multiple gestations, and vascular anomalies in the family [Citation5,Citation7]. HGMs usually occur after proliferation within several months to years without the need for interventions, but the complicated HGMs that are causing significant functional or cosmetic problems need management [Citation6,Citation8]. Surgical management is a suggestive option for complicated HGMs then the construction methods are followed [Citation4,Citation9]. One of the most common postoperative complications is the long-term cosmetic disfigurement, which is a great concern for both the patients and their families, furthermore using a proper plan of reconstruction is crucial [Citation4].

This paper presents a new technique of reconstruction after surgical removal of a face HGM by using surgical mesh.

Case presentation

Patient information

A 50-year-old male patient presented with right cheek swelling for more than 40 years duration. The lesion was causing pain and cosmetic issues for the patient with occasionally difficulty chewing food and nighttime bleeding by lying on the affected site and after removing hair on that area. No family history of hemangioma. The patient used medical treatment options available for hemangioma but they were ineffective.

Clinical findings

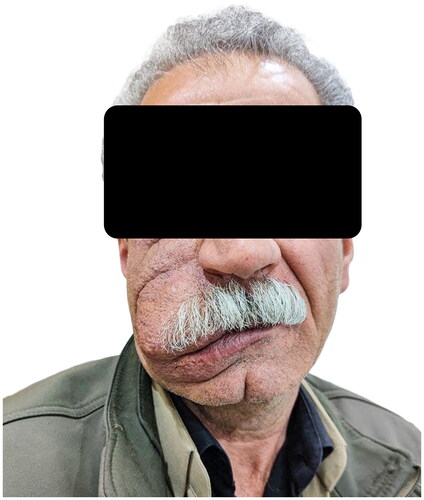

On physical examination, there was a red to blue colored large lesion covering a part of the right cheek and upper lip, soft to touch and fixed under the skin, slightly elevated from the skin, causing disproportion of the face ().

Diagnostic approach

In contrast CTA, there was a large 6 cm* 5 cm vascular mass lesion on the right side of the face with involvement of the adjacent cheek, upper lip, and adjacent muscular tissues. It showed intense vascularity with very large and dilated vascular arterial supply from one of the branches of the external carotid artery, also had a large venous drainage adjacent to the dilated artery and draining most of the internal jugular vein, suggesting large vascular malformation.

Therapeutic intervention

The patient was admitted to the surgical ward, preoperatively measures were taken for undergoing the resection of the lesion under general anesthesia. By nasolabial linear incision, a flap was raised from the incision down to the edge of the top lip and the surgical resection proceeded with minimal bleeding by ligating the feeding vessels and applying electrical coagulation to the minor vessels, marginal mandibular branch of the facial nerve explored and preserved, then a 4*2 cm lightweight, non-absorbable Prolene surgical mesh was put in the surgical bed and the mesh was covered by tetracycline antibiotic powder. The wound closed cosmetically and prophylactic antibiotics were given. The excised tissue was sent for histopathological examinations (HPE) and the results confirmed HGM.

Follow-up and outcome

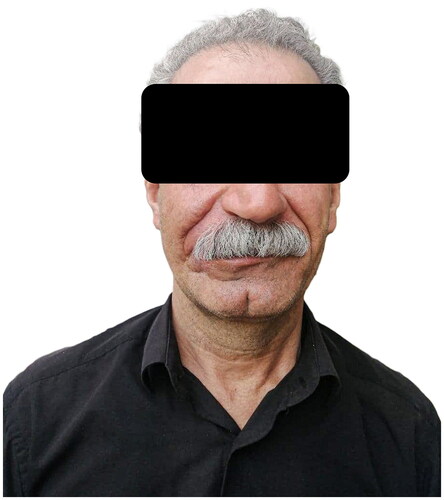

Twenty-four hours after the operation, the patient was sent home and followed up for any post-operative complications and suture removal, post operatively he just had swelling and inflammation. After more than two years follow up, the patient’s face is symmetrical with a normal facial contour ().

Discussion

HGMs called “strawberry marks” are vascular benign tumors that are the most common tumors of infancy arising from endothelial cell hyperplasia in about 5-10% of children [Citation4,Citation10]. The two types of HGMs are congenital HGMs which can be seen from birth and IHs appearing later in infancy or childhood, head and neck are the most commonly affected areas in about 60% of cases [Citation4]. The IHs pathogenesis is still unclear and there are different theories regarding it, the two dominant theories are: the first one suggests that they arise from disturbed tissue of the placenta implanted in the fetal soft tissue, and the second theory suggests that most likely hematopoietic progenitor cells (from the stem cells or the placenta) develop into IHs in the right environment of genetic and cytokines [Citation5,Citation7].

These lesions have a proliferating phase which grows fast for about 6 months to 1 year, then they stabilize for a period of time followed by natural involution over a few years differing from one person to another. About 49% of the cases are resolved without management by the age of 5 years while 72% of them by the age of 7 years, yet some of them need more time to involute up to 10 years. Generally, HGMs do not give rise to problematic consequences, still roughly 10 to 20% of cases may face complications from bleeding and ulceration to permanent disfigurement in 40% to 80% of cases as after regression residue of the lesion may be left in and possible functional impairment may follow [Citation5,Citation7,Citation11]. About 18% of patients experience local recurrences, with 7% of those cases experiencing multiple recurrences [Citation12].

Recently the acceptable treatment options are either medical or surgical approaches including systemic corticosteroids, intralesional corticosteroids, systemic B-blockers like propanol, topical beta-blockers such as timolol, surgery, laser treatments, and uncommonly interventional radiology procedures [Citation13]. Surgical management is generally reserved for the removal of hemangioma in these circumstances [Citation4]. In case of failure of improvement by medical therapy and regional wound care, the lesion should be resected and reconstructed [Citation14].

Most of the cosmetically disfigured HGMs are the ones that have failed to respond to medical interventions. Because of the serious side effects of using systemic therapy, eventually they were introduced to surgical excision because complete surgical excision is always the treatment of choice, as the case presented in this paper experiencing different medical therapy options without reaching the definite management [Citation7,Citation12].

In the present case of face HGM extending from the upper lip up to the cheek, the surgical excision was done by raising a local flap which was used as a classical approach for the reconstructions that involve or close to the lips as explained by Ebrahimi et al. that tumor resection followed by reconstruction in this area starts with simple procedures to complex ones, such as primary closures to local flaps onto free flaps and grafts depending on defect that the tumor resection leaves [Citation15]. Hauben back in 1988 used an apron- vermillion flap raised from the buccal area and then the excess flap was cut for better shaping [Citation16]. Also, Manafi and his colleagues used the Musculo-mucosal flap by Mutual Cross-Lip Musculo-mucosal and Ahmad-Ali flap which used the contralateral Musculo-mucosal layer of the lip as a flap [Citation17]. The applied flap type in the present case was a nasolabial flap and described as a good option in the manner of color and texture also declared by Gao W et al. who used this flap on eight cases in a hospital in China. The mentioned complications in their cases were hypertrophic scar, alar flaring, and bulking of the lower lid [Citation18].

Another approach of reconstruction in the literature is fat grafting as presented in the retrospective study conducted by Yin J et al. for twelve patients with lip hemangioma who were exposed to this technique after HGM treatment. The treatment was given in multiple sessions which required long-term (twenty-four months) follow-up [Citation19]. Terenzi et al. presented a case where severe progressive hemifacial atrophy was addressed through a combination of treatment methods utilizing biomaterials. Hard tissue reconstruction was achieved using Medpor, while Bio-Alcamid was utilized to restore the soft tissues. Additionally, a V-Y plasty procedure was carried out on the labial mucosa. The results of these interventions led to significant cosmetic enhancement, meeting the patient’s expectations effectively [Citation20]. In another paper, Qi Y et al. applied two different approaches either combined or alone: Nano-fat grafting alone or combined with local flap for a series of twenty-four patients. The results of the combined technique were more satisfactory with some complications such as the inability to whistle [Citation21].

The above-mentioned complications were not faced in the case presented in this paper, while a novel technique was introduced that used surgical mesh other than local flap. The use of surgical mesh for cosmetic and anatomical support measures has a long history, but using it in a post-surgical removal of HGM was a novel technique where the resected tumor bed was covered by an appropriate surgical mesh size for the wound then the wound closed. This technique provided a satisfactory outcome without any significant complications. A thorough review of the genuine literature failed to find a case of resected hemangioma of the face, reconstructed by a mesh as the current case [Citation22].

In conclusion, the application of surgical mesh for patients who seek functional and cosmetic improvements after hemangioma removal might be an option. This might be done without significant complications.

Informed consent

The patient provided written consent for the publication of this case report and any associated images after being informed about it.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to disclose regarding the publication of this case report.

References

- Covelli E, De Seta E, Zardo F, et al. Cavernous haemangioma of external ear canal. J Laryngol Otol. 2008;122(8):e19. doi: 10.1017/S0022215108002909.

- Covelli E, Margani V, Trasimeni G, et al. A case of cavernous hemangioma of the infratemporal fossa causing recurrent secretory otitis media. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2022;88(6):999–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.bjorl.2021.03.001.

- Abdullah AS, Ahmed AG, Mohammed SN, et al. Benign Tumor Publication in One Year (2022): a Cross-Sectional Study. Barw Med J. 2023;1:20–25.

- Chamli A, Aggarwal P, Jamil R, et al. Hemangiom Ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538232/.

- Satterfield KR, Chambers CB. Current treatment and management of infantile hemangiomas. Surv Ophthalmol. 2019;64(5):608–618. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2019.02.005.

- Saaiq M, Ashraf B, Siddiqui S, et al. Successful propranolol treatment of a large size infantile hemangioma of the face causing recurrent bleeding and visual field disruption. World J Plast Surg. 2015;4(1):79–83.

- Richter GT, Friedman AB. Hemangiomas and Vascular Malformations: current Theory and Management. Int J Pediatr. 2012;2012:645678. doi: 10.1155/2012/645678.

- Kawaguchi A, Kunimoto K, Inaba Y, et al. Distribution analysis of infantile hemangioma or capillary malformation on the head and face in Japanese patients. J Dermatol. 2019;46(10):849–852. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.15051.

- Laurian L-J, Decaudaveine S, Caillot A, et al. Case report of a zygomatic bone hemangioma surgery with reconstruction by a custom-made implant. J Stomatol Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2022;123(6):660–662. doi: 10.1016/j.jormas.2022.06.019.

- Macca L, Altavilla D, Di Bartolomeo L, et al. Update on treatment of infantile hemangiomas: what’s new in the last five years? Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:879602. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.879602.

- Boscolo E, Bischoff J. Vasculogenesis in infantile hemangioma. Angiogenesis. 2009;12(2):197–207. doi: 10.1007/s10456-009-9148-2.

- Allen PW, Enzinger FM. Hemangioma of skeletal muscle. An analysis of 89 cases. Cancer. 1972;29(1):8–22. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197201)29:1<8::AID-CNCR2820290103>3.0.CO;2-A.

- Menapace D, Mitkov M, Towbin R, et al. The changing face of complicated infantile hemangioma treatment. Pediatr Radiol. 2016;46(11):1494–1506. doi: 10.1007/s00247-016-3643-6.

- Krowchuk DP, Frieden IJ, Mancini AJ, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of infantile hemangiomas. Pediatrics. 2019;143(1):e20183475. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3475.

- Ebrahimi A, Kalantar Motamedi MH, Ebrahimi A, et al. Lip Reconstruction after Tumor Ablation. World J Plast Surg. 2016;5(1):15–25.

- Hauben DJ. Reduction cheiloplasty for upper lip hemangioma. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1988;82(4):694–697. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198810000-00025.

- Manafi A, Ahmadi Moghadam M, Mansouri M, et al. Repair of large lip vermilion defects with mutual cross lip musculomucosal flaps. World J Plast Surg. 2012;1(1):3–10.

- Gao W, Jin Y, Lin X. Nasolabial flap based on the upper lateral lip subunit for large involuted infantile hemangiomas of the upper lip. Ann Plast Surg. 2020;84(5):545–549. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000002030.

- Yin J, Li H, Yin N, et al. Autologous fat grafting in lip reconstruction following hemangioma treatment. J Craniofac Surg. 2013;24(2):346–349. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e318288b917.

- Terenzi V, Leonardi A, Covelli E, et al. Parry-romberg syndrome. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116(5):97e–102e. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000182402.58757.b9.

- Qi Y, Ma G, Liu Z, et al. Upper lip reconstruction utilizing a two-stage approach with nanofat grafting after hemangioma treatment. Facial Plast Surg Aesthet Med. 2021;23(4):303–308. doi: 10.1089/fpsam.2020.0076.

- Aso SM, Jaafar OA, Hiwa OB, et al. Kscien’s list; a new strategy to discourage predatory journals and publishers (second version). Barw Med J. 2023;1(1):24–26. doi: 10.58742/bmj.v1i1.14.