Abstract

Kaposi’s Sarcoma (KS) is a rare malignant tumor of blood vessel endothelial cells with a bleeding tendency. KS is relatively uncommon in the general population. However, its incidence significantly increases in people living with HIV. This article reports a rare case of nasal Kaposi’s Sarcoma. Understanding the clinical presentation of this disease and its association with HIV is crucial for ENT doctors, emphasizing the importance of early diagnosis and treatment of KS. A case of Kaposi’s sarcoma in the nasal cavity was reported. The patient had a history of AIDS and was being treated with highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). He presented with a 3-month history of progressive swelling on both sides of his nose. The pathology diagnosis was Kaposi’s sarcoma. The lesion lessened after 3 times of chemotherapy. Nasal Kaposi’s Sarcoma (KS) typically presents as purplish-red or purplish-black spots, patches, or lumps in the nasal cavity. Patients may experience local symptoms like nasal congestion, pain, or bleeding, and they may also exhibit systemic symptoms such as fever, fatigue, and weight loss. In patients without a history of immune suppression, consideration should be given to the possibility of HIV infection. Purely nasal KS often responds well to HAART treatment and may not require surgical excision.

Introduction

Kaposi’s Sarcoma (KS) is a rare malignancy originating from blood vessel endothelial cells, caused by Kaposi’s Sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) or human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8), characterized by hemorrhagic lesions [Citation1]. Based on different causes and clinical manifestations, KS can be classified into four main types: 1. Classic Kaposi’s Sarcoma: Mainly affects elderly men from Mediterranean, Eastern European, and Middle Eastern regions. Lesions develop slowly and typically appear on the skin of the lower extremities. 2.Epidemic (AIDS-related) Kaposi’s Sarcoma: Seen in patients living with HIV/AIDS. Lesions can appear on the skin, oral cavity, gastrointestinal tract, and respiratory system, and are more aggressive. 3. Endemic (African) Kaposi’s Sarcoma: Primarily affects children and young adults in sub-Saharan Africa. Lesions can involve the skin, lymph nodes, and internal organs. 4. Iatrogenic (transplant-related) Kaposi’s Sarcoma: Occurs in patients who have undergone organ transplants and are receiving immunosuppressive therapy. Lesions can appear on the skin or internal organs [Citation2].

KS is relatively rare in the general population (incidence rate of 1.53 per 100,000), especially among those not infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). However, in people living with HIV, the incidence of KS increases significantly (1397 per 100,000) [Citation1,Citation3]. In fact, HIV infection is one of the major risk factors for KS. In patients living with HIV, especially when HIV viral load is uncontrolled and CD4 lymphocytes are decreased, the T cell response is weakened, and infection with KSHV or HHV-8 leads to the development and progression of KS. In patients living with HIV, KS can affect the skin, oral cavity, nasal passages, throat, and internal organs [Citation4]. Additionally, other tumors and diseases associated with KSHV include KICS (KSHV inflammatory cytokine syndrome), PEL (primary effusion lymphoma), and MCD (multicentric Castleman disease) [Citation5].

Due to the increasing incidence of this rare condition in the field of otolaryngology, this article aims to enhance the understanding of this disease among ENT specialists by reporting a case of nasal KS.

Case report

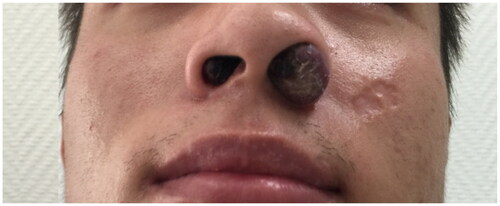

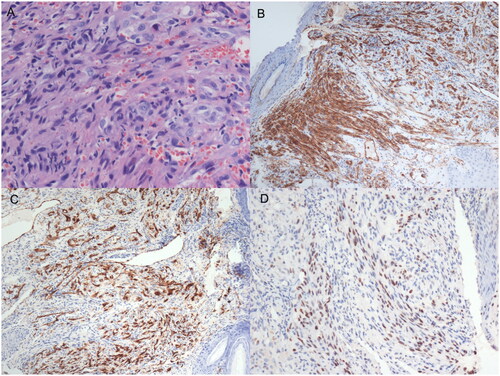

A 26-year-old Asian man presented with a 3-month history of progressive swelling on both sides of his nose. He also had a history of HIV infection and was under highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) (TDF + 3Tc + Lpv/r) for 1 year. A sinoscopic examination appeared a bulging nodule out of the left nostril, a smaller nodule on his right anterior nasal floor near the nostril (Figure ). No similar lesions were found in other parts of the body. Serological tests for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) antigen/antibody were positive. HIV RNA499149 copies/ml, CD4+T was 14/UL. A biopsy was undertaken for the suspicion of neoplasm, histological analyses under hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining revealed a nodular tumor. The tumor was composed of plump, spindled tumor cells with mild to moderate nuclear atypia. The tumor cells spaces containing erythrocytes (Figure ). Eosinophilic hyaline globules were seen in some tumor cells (Figure ). Inflammatory cells, chiefly lymphocyte, and ectatic vessels were seen at the periphery of the tumor. Immunohistochemical (IHC) stains revealed that the tumor cells were strongly positive for CD31 (Figure ), CD34 (Figure ), and human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) antibody (Figure ). The final pathology diagnosis was KS. Chemotherapy medicine was prescribed, mainly with doxorubicin hydrochloride liposome 40 mg per 14 days 6 times. The lesion narrowed down after 3 cycles of Chemotherapy. While adjusting the HAART regimen(TDF + FTC + DTG), at the end of the treatment course, HIV RNA was undetectable, CD4+ T cells were at 290/µL, and the nasal mass in the patient had significantly reduced. The patient provided consent for publication of the case report.

Figure 1. An examination showed a red bulging nodule out of the left nostril without surface hemorrhage or breakage; a smaller nodule on his right nostril.

Figure 2. An IHC examination showed endothelial cell proliferation, fibroblast proliferation pericapillary, spindle cells were mild to moderate dysplasia, pathological mitosis was observed. (A) Erythropoietic hyaline corpuscles were found in the cells, red blood cells exuded and hemosiderin particles were deposited between the cell(HE × 200); (B) CD31 of tissue cell markers are positive in IHC staining(CD31 × 100); (C) CD34 of tissue cell markers is positive in IHC staining(CD34 × 100); (D) HHV-8 markers are positive in IHC staining(HHV-8 × 100).

Discussion

The occurrence of KS is associated with Kaposi’s Sarcoma-Associated Herpesvirus (KSHV), also known as HHV-8, an oncogenic lymphotropic virus belonging to the herpesvirus family, similar to the Epstein-Barr virus. KSHV infection can be transmitted through various routes, such as saliva, sexual contact, and blood. Among immunocompromised individuals, particularly those with HIV/AIDS, the infection rate of HHV-8 is 39%. HHV-8 infection may suppress the expression of tumor suppressor genes, potentially contributing to the pathogenesis of KS [Citation6–8].

The most common sites for head and neck KS are the oral cavity (67%), oropharynx (65%), and skin (39.1%). In contrast, the involvement of the larynx (10.9%), hypopharynx (8.7%), lymph nodes (6.5%), and nasal mucosa (4.3%) is less frequent [Citation9].Primary nasal cavity Kaposi’s Sarcoma is exceptionally rare, with only seven reported cases previously, the majority of which were associated with immunodeficiency syndrome [Citation6,Citation9–12].

The lower prevalence of nasal cavity Kaposi’s Sarcoma (KS) compared to oral cavity KS may be attributed to the following factors:1.Tissue Characteristics: Oral and nasal tissues have distinct biological characteristics. Oral mucosa is more susceptible to external factors such as food, microorganisms, viruses, which might increase the risk of oral KS. In contrast, nasal tissues are relatively protected, resulting in a lower incidence.2. Exposure Risks: Oral tissues are more exposed to the effects of sexual behaviors, oral sex, oral inflammations, and other transmission routes, which may elevate the risk of oral KS. In contrast, the nasal cavity is less frequently associated with these routes, reducing exposure risk. 3. Immune System Role:The immune system plays a critical role in controlling the development of KS. Oral mucosa is often exposed to a substantial amount of microorganisms and antigens, potentially triggering immune responses more readily. The nasal cavity, due to its relatively enclosed nature, encounters fewer microorganisms and antigens, decreasing the chances of immune system stimulation and, subsequently, reducing the likelihood of KS. 4.Viral Load: KS is closely associated with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) infection. Among people living with HIV, viral loads can vary due to individual differences, affecting the incidence of KS. It’s possible that oral and nasal tissues carry different viral loads, potentially explaining the differing rates of occurrence between these two sites. In summary, oral mucosa is often a primary entry point for Kaposi’s Sarcoma-Associated Herpesvirus (KSHV) infection in the human body, given its prevalence in the oral cavity. Chronic oral inflammations, mucosal damage, or other mucosal issues may facilitate KSHV infection [Citation7,Citation11].

The clinical presentation of KS typically manifests as isolated nodules or tumors on the skin or mucous membranes. These tumors usually grow painlessly and rapidly. Early lesions often appear as flat or slightly raised spots, progressing to raised patches or lumps, which can vary in color, including purple, brown, or red. Over time, the tumors evolve into infiltrative patches, and in the late stages, they may disseminate systemically, affecting almost all internal organs, including lymph nodes, liver, pancreas, heart, testes, bone marrow, bones, muscles, and the mucous membranes of the head and neck. In patients with nasal cavity tumors, there is often a history of chronic nasal congestion and recurrent nasal blockage or nosebleeds. In our case, the patient presented with the symptoms of purplish-red growths in both nasal passages, nasal congestion, and occasional mild nosebleeds [Citation13].

The histologic differential diagnosis of Kaposi’s sarcoma in this unusual position is broad. IHC test is helpful for the diagnosis of KS. Its histological features include early chronic granulomatous inflammation, formation of neovascularization and lymphatic vessels accompany with edema and hemorrhage, transparent bodies can be seen in the cells, blood cells exudates and iron-containing hemosiderin granules deposit among the cells; in the late stage, endothelial cell proliferation, fibroblast proliferation pericapillary, spindle cells were mild to moderate dysplasia, pathological mitosis was observed. CD31, CD34 of tissue cell markers is definte in IHC staining [Citation14].

The identification of KS includes the following diseases: 1 Nasopharyngeal fibroangioma. The positive tissue markers are CD34, smooth muscle actin and the wave protein; 2 malignant lymphoma. For the most part, it accompanied by systemic wasting symptoms, such as emaciation, night sweating, anemia etc. Positive tissue markers are CD10, CD20 and BCL6; 3 olfactory neuroblastoma. The clinical feature is grayish pale or else pale red mass in the ethmoidal plate of the nasal cavity which was indistinct from the surrounding tissue. IHC staining appeared S-100 and NSE was positive. 4 Angioleiomyomas. It lacks of specific symptoms. IHC examination of calponin, desmin is positive [Citation15,Citation16]

The treatment of KS in the field of otorhinolaryngology typically involves local treatment methods such as surgical excision, laser therapy, cryotherapy, or localized radiation therapy. It is noteworthy that for patients with AIDS-related KS (AIDS-KS), when they undergo highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), most KS lesions tend to stabilize or even completely regress by lowering HIV plasma viremia and achieving immune reconstitution, often eliminating the need for further specific treatments. In this case, the patient’s KS lesions were not surgically removed but significantly reduced in size with a combination of systemic chemotherapy and HAART. This emphasizes the importance of a multidisciplinary assessment to determine the most suitable treatment approach for KS, especially in patients with concurrent AIDS. Such a comprehensive treatment approach can help improve the patient’s condition and prognosis [Citation17].

While most KS patients have a favorable prognosis, those in advanced stages of AIDS or with rapidly progressing disease, particularly those with immune reconstitution syndrome who have not received cytotoxic chemotherapy, have a poorer prognosis. For example, in Africa, reports indicate that 50% of KS patients have died or were lost to follow-up within 1 year of KS diagnosis [Citation18].

In summary, while Kaposi’s Sarcoma (KS) is relatively uncommon, its incidence has been rapidly increasing with the prevalence of AIDS. This underscores the urgency of raising awareness among healthcare professionals about this condition, as early diagnosis and interdisciplinary treatment are crucial for the management of KS.

Authors’ contributions

Jing Hou was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Consent for publication

All case report presentations have consent for publication.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the ethics committee of Beijing Ditan Hospital.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no financial interest in any companies or other entities with an interest in the information presented in this contribution.

References

- Reiner AS, Panageas KS. Kaposi sarcoma in the United States: understanding disparate risk. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2022;6(6):pkac079. doi:10.1093/jncics/pkac079.

- Bishop BN, Lynch DT. Kaposi sarcoma; 2022.

- Rios A. Kaposi sarcoma: a fresh look. AIDS. 2021;35(3):515–516. doi:10.1097/QAD.0000000000002756.

- Clutton GT, Weideman A, Goonetilleke NP, et al. An expanded population of CD8(dim) T cells with features of mitochondrial dysfunction and senescence is associated with persistent HIV-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma under ART. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2022;10:961021. doi:10.3389/fcell.2022.961021.

- Dumic I, Radovanovic M, Igandan O, et al. A fatal case of Kaposi sarcoma immune reconstitution syndrome (KS-IRIS) complicated by Kaposi sarcoma inflammatory cytokine syndrome (KICS) or multicentric castleman disease (MCD): a case report and review. Am J Case Rep. 2020;21:e926433. doi:10.12659/AJCR.926433.

- Marando A, Isimbaldi G, Servillo SP, et al. Pleural Kaposi sarcoma: an unusual clinical case. Pathologica. 2022;114(5):381–384. doi:10.32074/1591-951X-778.

- Gómez I, Pérez-Vázquez MD, Tarragó D. Molecular epidemiology of Kaposi sarcoma virus in Spain. PLoS One. 2022;17(10):e274058. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0274058.

- Lange P, Damania B. Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV). Trends Microbiol. 2020;28(3):236–237. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2019.10.006.

- Agaimy A, Mueller SK, Harrer T, et al. Head and neck Kaposi sarcoma: clinicopathological analysis of 11 cases. Head Neck Pathol. 2018;12(4):511–516. doi:10.1007/s12105-018-0902-x.

- Soon G, Petersson F, Thong M, et al. Primary nasopharyngeal Kaposi sarcoma as index diagnosis of AIDS in a previously healthy man. Head Neck Pathol. 2019;13(4):664–667. doi:10.1007/s12105-018-0954-y.

- Barron K, Omiunu A, Celidonio J, et al. Kaposi sarcoma of the Larynx: a systematic review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2023;168(3):269-281. doi:10.1177/01945998221105059.

- Osei N, Fletcher G, Showunmi A, et al. A case of non-cutaneous Kaposi sarcoma. Cureus. 2022;14(12):e32394. doi:10.7759/cureus.32394.

- Rusu-Zota G, Manole OM, Gales C, et al. Kaposi sarcoma, a trifecta of pathogenic mechanisms. Diagnostics (Basel). 2022;12(5):12. doi:10.3390/diagnostics12051242.

- Addula D, Das CJ, Kundra V. Imaging of Kaposi sarcoma. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2021;46(11):5297–5306. doi:10.1007/s00261-021-03205-6.

- Dupin N. Update on oncogenesis and therapy for Kaposi sarcoma. Curr Opin Oncol. 2020;32(2):122–128. doi:10.1097/CCO.0000000000000601.

- Erturk YT, Akay BN, Okcu HA. Dermoscopic findings of Kaposi sarcoma and dermatopathological correlations. Australas J Dermatol. 2020;61:e46-53.

- Goyack LE, Heimann MA. Disseminated Kaposi sarcoma. Clin Pract Cases Emerg Med. 2021;5(4):491–493. doi:10.5811/cpcem.2021.9.53692.

- Htet KZ, Waul MA, Leslie KS. Topical treatments for Kaposi sarcoma: A systematic review. Skin Health Dis. 2022;2(2):e107. doi:10.1002/ski2.107.