ABSTRACT

Biosecurity is a crucial issue in a globalised world as today. Biosecurity has become a serious concern for some countries to prevent the transfer of any infectious diseases across borders. Involving human bio-surveillance, biosecurity regulation is actually an attempt to build new spatial demarcations in the border areas of countries. In the context of Indonesia, the biosecurity policy so far has been initiated and applied for protecting Indonesian borders from infectious disease transferred from the mobility of people, including Indonesian migrant workers when they returned back to this country. However, some important issues and controversies remain in debate, especially around the political economy discourses of the Indonesian government. This research, thus, focuses on the risk of disease transmission among the Indonesian migrant workers, which could affected not only Indonesia, but also others particular countries and global people’s health. This study examines the case of biosecurity issue in the border Island of Indonesia, which is Tanjung Pinang situated in Riau Islands. Tanjung Pinang is an offshore bordered area bordering to Singapore, Malaysia, Vietnam, and the Philippines. This place is part of a major maritime traffics lane between its neighbouring countries. Tanjung Pinang is also one of departure harbours for the Indonesian migrant workers to Malaysia and Singapore. Upon interviewing with migrant workers, the government representatives, and the NGOs/agents who have involved with migrant workers’ travels, this research found that biosecurity policy of the Indonesian government has not been implemented consistently and firm to the standard of health protocols; whilst, the prevention of infectious desease carried from migrant workers overseas who returned home could be spread out and brought health risks for domestic communities. The health authority in border area, i.e. Tanjung Pinang, has provided screening rooms; yet, the screenings were implemented for some random workers and on the workers’ physical body.

Introduction

There have been various studies focusing on the transmissions of diseases brought by human migrations such as STD and HIV/AIDS (Herdt, Citation1997); Hepatitis B (Thijssen et al., Citation2019); influenza A or H1N1 2009 (Nelson et al., Citation2015), SARS, MERS, malaria and tuberculosis (Vignier & Bouchaud, Citation2018); measles (Beay, Citation2018); malaria (Beay et al., Citation2017); and recently, COVID-19 (Araujo & Naimi, Citation2020; Poirier et al., Citation2020; Sajadi et al., Citation2020; World Health Organization, Citation2020, Citation2020). Some of these studies suggested that the major group that have predominantly being the carrier agent and spread those infectious diseases related to migration are migrant workers (Cayuela et al., Citation2018a). According to the data released by ILO, there are around 150.3 million migrant workers globally (Ilo, Citation2015), and these people have been categorised as risk people who could become potential agent of particular infectious diseases. Migrant workers are vulnerable to disease transmission so far, not only in Asian regions, but also in other parts of countries. For instances, migrant workers from Thailand are potential carrier of malaria disease in Thailand (Kitvatanachai & Rhongbutsri, Citation2012); migrant workers in Singapore had been diagnosed bringing in Zika virus in Singapore (Tam et al., Citation2016); some workers in the Middle East brought Tuberculosis disease in Lebanon (Fernandez, Citation2018), reproductive and sexual health in Malaysia, HIV in Korea (Lee, Citation2008), malaria, hepatitis A and E, and tuberculosis in Singapore (Sadarangani et al., Citation2017); Others have also been identified brought in sexually transmitted diseases in South Florida (Sánchez, Citation2015); HIV infection in the United States (Albarrán & Nyamathi, Citation2011); COVID-19 disease in China (Chen et al., Citation2020; Leung et al., Citation2020; Liem et al., Citation2020; Qiu et al., Citation2020), in Singapore (Moroz et al., Citation2020); and in the United States (Gelatt, Citation2020).

From the above mentioned incidents, governments around the world have implemented and proposed policies and regulations for all countries to protect the rights of individuals and citizens within the framework of achieving the global health through the creation of ‘biosecurity’ policy. According to Warren, biosecurity or biological security in the offshore border area is essential and needed to be implemented in cross-border places around the countries in the world by building new space demarcation for the prevention of infectious diseases and for bio-surveillance (Warren, Citation2013).

In the context of Indonesia, the Indonesian government has attempted to create policy to protect larger society from being infected from returning migrant workers to their villages. According to data from Indonesian Migrant Workers Protection Board, known as, and hereafter BP2MI (BP2MI, Citation2022), reporting that the numbers of Indonesian migrant workers (hereafter, IMW) working abroad were 200.761 people in 2022. This number increased compared to the previous year, which was 72.624 persons. The COVID-19 pandemic outbreak in 2020 and 2021 had caused the placement of IMWs to go overseas dropped by less than 200.000 people due to many countries closed their doors for overseas arrivals. The migrant workers who work overseas predominantly come from East Java province. In 2022, there were 51,348 people or one-third of the national figures. Other provinces such as Central Java contributed to send migrant workers for 47,480 people and West Java were 33,285 people. These three provinces have become the barometer of the Ministry of Health to pay significant attention to the spreading of infectious diseases carried in by migrant workers who returned back to their home town.

Bintan is one of outer Islands in Indonesia positioned its location in the border of Singapore and Malaysia. Many migrant workers, both illegal and legal, cross-passing this Island to find jobs, especially in Malaysia, then to other countries such as Hong Kong, Taiwan, and the Middle East. Bintan is situated in Riau Islands Province. It is only one hour from this place to take a ferry or small boat to reach Singapore and/or Johor Malaysia. The local people of Bintan quite frequent in cross-passing to Singapore and Malaysia. The locals shared common histories and stories as Malay people and culture, so they feel culturally similar to these two places, but foremost, is Johor, Malaysia. Bintan Island has long become the target of migrant workers crisis, especially with those illegal workers; making Bintan becomes crucial border area for health screening for the mobility of Indonesian migrant workers who go outside and return back to the country. Tanjung Pinang is the capital of Bintan Island, which provides migrant workers care centre, including a health screening test centre for migrant workers. Another reason for selecting the place is triggered by the previous studies that suggested the importance to understand the impact of disease transmission among migrant workers (Hollweck, Citation2015; Kõu et al., Citation2015), which considered crucial. According to Kõu and Bailey, migration can be seen as a process and not an event; thus, the entire migration process is the context which shapes the events before, during and after migration (Kõu & Bailey, Citation2014).

It has been acknowledged by Ulrich Beck that the opening of labour market that is not accompanied by biosecurity policy at the time of discharge will face risk society against disease transmission (Beck, Citation1992). This condition can also be occurred in the context of Indonesia. It is, therefore, this study is aimed at investigating the model of biosecurity policy in border island, and the practices initiated by the Indonesian government to screening the health condition and to protect the transmission of infectious disease into the larger community. The problems raised in this paper are: first, how has a border biosecurity policy and its practices being implemented for Indonesian migrant workers who return back to the country? Second, how do the role of Indonesian migrant workers protection board (UPT-BP2MI) and other related agencies, the health officers in the port, to prevent the coming of risk individuals and their health screening? Third, what are the strategies that need to be developed in preventing infectious diseases and what are the barriers and potential challenges to implement biosecurity policy in border place?

There are quite rare to find studies on biosecurity policy and implementation in the Indonesian context. So far, studies on biosecurity for migrant workers have been attempted to cover the context of Southeast Asia (Cicero et al., Citation2019) and one article on biosecurity in West Timor (Mudita, Citation2013), but not related to specifically migrant workers. This study, thus, emphasises the risk of infectious diseases carry out by the returned migrant workers in Indonesian border Island, i.e. Bintan Island, to look at the impact of globalised risk of diseases due to the weakness of biosecurity policy implementation. This research will reveal the danger of opening the labour market by sending IMWs abroad but not be followed by the strong process of biosecurity procedures upon the arrival of migrant workers to their hometown, which in turn it will face a greater risk society against those infectious diseases. This study argues that in the era of reflexive modernity, the process of globalisation has beyond the borderlines of the nation-state through migration and mobility which have been responded by the Indonesian government by opening the market labour opportunity and sending migrant workers to work overseas. Nevertheless, another aspect of migration, that is spreading the infectious diseases, seems to be less controlled and not seriously implemented in order to prevent the larger communities from being infected by the globalised disease risks.

Methods

This study employs a descriptive research with a qualitative approach, focusing on the location of the research in Tanjung Pinang, the capital of Bintan Island. This place is strategic for this present study since this island’s offshore borders with foreign countries (Singapore and Malaysia), its access to traffic roads, and the place of departure for Indonesian migrant workers (IMWs) to Malaysia and Singapore then to other countries. Data collections involve observation and focus group discussions to identify problem with health screening procedures and practices, the attitude of IMWs towards the prevalence of infectious diseases and health risks, including the role of P3MI Agencies, NGO activists, government agencies, and local figures. This research involved 10 key informants consist of 5 the retirements IMWs, 2 NGOs, 2 government agencies (BP2MI), and 1 local figure. The selected informants of retirement Indonesia Migrant Workers were 5 people with the criteria IMWs with infectious disease, and has been quarantine at least 6 days in shelter

Apart from that, this study also includes in-depth interviews with informants who share details of migrant workers suffering from communicable diseases, such as hepatitis B, hepatitis C, HIV/AIDS, COVID-19, and sexually transmitted infectious diseases (STIDs), such as Chlamydia, Gonorrhea, and Syphilis. This study also interviewed some informants, who are married couples and decided to become migrant workers in order to gain more insights the experience of the couples in dealing with infectious diseases risk, whilst they have been separated. Consent from the couples and other migrant workers interviewed had been gained, and their names are camouflage and being kept privately.

Results and discussion

Indonesia’s “biosecurity” policies related to migration health screening

The International Health Regulations (IHR), which were introduced in 2005 to replace the former version of IHR (1969), aims to prevent, protect and control the spread of infectious disease across countries by taking actions according to the health risks faced without causing significant disruption (World Health Organization, Citation2008). The term ‘diseases’ referred to in the IHR are infectious diseases that already existed, new versions, and re-emerging outbreaks (Merianos & Peiris, Citation2005). Migration has a significant role in the spread of disease in the world, it is from this movement that disease outbreaks can occur (Chakraborty & Maity, Citation2020). Globalization has resulted in increased mobility of humans and animals across countries, and changes in human lifestyles have also contributed to accelerating the process of spreading epidemics to become a threat to global health security (Mahendradhata et al., Citation2021). Examples of the spread of disease outbreaks that occur due to the movement of humans and animals across countries are the outbreak of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) in the Asian region in 2003 (Zhou & Yan, Citation2003), the outbreak of the avian influenza virus (H5N1) in 2004 (Webster et al., Citation2005), swine flu/swine influenza (H1N1) virus in 2009 (WHO declared as the first pandemic in the 21st century) (Gangurde et al., Citation2011), Middle East Respiratory Syndrome-Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) in 2012–2013 (Sikkema et al., Citation2019), Ebola in 2014 (Kaner & Schaack, Citation2016), and Zika Virus in 2015 (Zika et al., Citation2015), and SARS COVID-19 in Southeast Asia (Fauzi & Paiman, Citation2021).

With the process of repatriating retired IMWs who are infected with infectious diseases to Indonesia to their place of origin without medical screening or do medical screening but not followed the procedure properly, will create boomerang effect in global society. The process of returning retired IMWs in this study is emphasised after the formation of Law number 18/2017, and it was ratified on 22 November 2017. This law regulated the protection of IMWs, including health risk. During the COVID-19 outbreaks, the Indonesian government implemented this regulation and implemented new regulations as suggested by the WHO; since then, there have been two procedures for returning retired IMWs to the country. The periods before the COVID-19 pandemic and during the COVID-19 pandemic, the process of repatriating retired IMWs to Indonesia using different policies, especially related to medical screening. These regulations implemented to prevent the same risks for the distribution of infectious diseases in the migrant workers’ hometown, and could pose serious threat also to the larger communities in Indonesian and globally threat to the international health system.

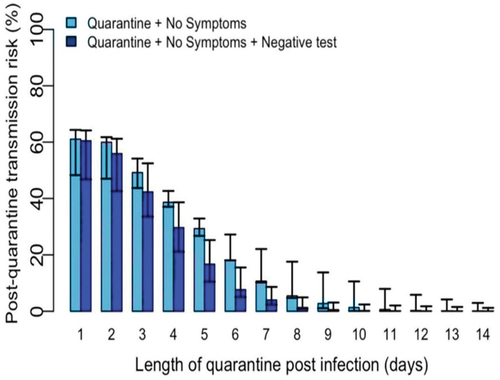

During the research, the researchers found that entry port, namely Sri Bintan Pura in Tanjung Pinang, migrant workers when they returned to Indonesia remains problematic and undocumented. According to the data from the Repatriation and Trauma Center for Indonesian migrant workers (known as and hereafter, RPTC) in Tanjung Pinang, during August 2023, the RPTC received 1,698 migrant workers who returned back to Indonesia were undocumented, or illegal workers, consisting of 1,099 males, 553 females, 34 children, and 12 toddlers. These workers mainly are from West Nusa Tenggara (NTB) Province and East Java Province (see ), and they returned to their homes in various villages.

Figure 1. The distribution of Indonesia migrant workers original hometown 2023 based on Ministry of Social Affair Republic of Indonesia 2023.

Based on the RPTC is actually under the control of the Ministry of Social Affairs, which has an obligation to give protection for all Indonesian citizens in the country, including the repatriation of retired IMWs; from the RPTC to the reintegration process in the area of origin. To return back to migrant workers’ hometown, the Ministry of Social Affairs makes coordination with UPT BP2MI, P3MI, district/city Health Office, and local NGOs (Habibullah et al., Citation2016). The RPTCs in Indonesia can be found in three different places, they are in Tanjung Pinang (Bintan Island), Bambu Apus (Jakarta), and Pontianak (West Kalimantan). The RPTC is not a quarantine or biosecurity place, but it is a temporary shelter and lodging facility which only accommodates maximum of 400 people consisting of 200 for males and 200 for females. After the COVID-19 pandemic, the Indonesian immigration eased of its border closure and no health quarantine policy, numbers of migrant workers returned back to Indonesia reached its peak by 1,698 people in August 2023, and those workers were considered illegal or undocumented workers and some of them were indicated carried diseases to home. With these large numbers of workers, of course the RPTC was unable to accommodate them all, and it was a chaotic situation. The condition in Tanjung Pinang’s RPTC was even worst, there was no separation place between the workers with communicable and those with non-communicable diseases. As stated by the accompanying officer for the Tanjung Pinang RPTC in our personal interview: ‘Here (the RPTC) shelters do not have any sepecific room for infectious diseases, so this causes transmission of diseases, such as HIV, which we know. many of workers were get contagious from outside (overseas)’. Unhealty condition of RPTC shelter has contributed to the potential disease transmission (Dewanti et al., Citation2021). It was a case in RPTC Jakarta, when two female migrant workers, namely N and R, who stayed at the Bambu Apus’ RPTC in Jakarta, after being returned from the Indonesian Embassy in the United Arab Emirates. These female workers gained contagious disease during their stay in the Center from other colleague workers.

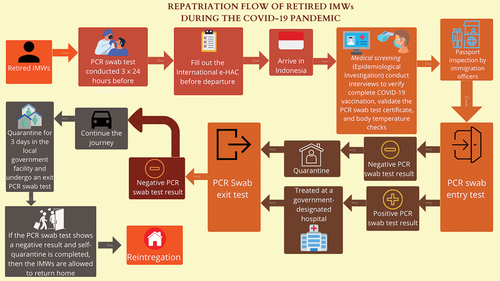

In the era of reflexive modernity, the State has not run the obligation to provide protection for migrant workers including the return of retired workers to the reintegration process in their place of origin or hometown. This will be at risk of reproducing and (re)reproducing risk, which is infectious diseases, in the hometown of IMWs. Data from the Ministry of Social Affairs of the Republic of Indonesia, Directorate General of Social Rehabilitation (2023), shows that IMWs illnesses handled by the RPTC from 2019 to August 2023 were ranging from infectious skin diseases, respiratory problems, cephalgia, myalgia, gastritis, constipation, gerd, stroke, hypertension and others. Skin diseases and acute respiratory infection were the highest infectious diseases found in Tanjung Pinang’s RPTC (see ).

Figure 2. The prevalence diseases in RTPC Tanjung Pinang 2019-august 2023 based on the data from the Ministry of Social Affair Republic of Indonesia.

Meanwhile, according to the data from the Ministry of Marine and Fishery of the Republic of Indonesia, cases of infectious diseases handled this Ministry in the last five years from 2019 to August 2023 were Tuberculosis (TB) (see ).

Table 1. The cases of infectious diseases handled by Ministry of Marine and Fishery of Republic of Indonesia.

As can be seen from , it shows that in accordance with the derivative regulations from the Ministry of Health, namely Ministerial Regulation No.1501/MENKES/PER/X/2010 and Regulation of the Minister of Health No. 29/2013 regarding the prevention of infectious diseases, the State should be present to protect IMWs. Under these regulations, the Indonesian government must assign health workers to exercise migrant workers during the pre-departure, departure, and repatriation processes. For retired IMWs, the health workers must conduct health quarantine carefully with the correct procedures as stated on the standard of operating procedure.

At the same time, the Ministry of Marine and Fishery of the Republic Indonesia has a significant role as an epidemiological surveillance that attempts to control infectious diseases carried from returned migrant workers via seaport and from fishermen who have returned from overseas. The Ministry of Marine and Fishery of Republic Indonesia must be more active in carrying out its role in Epidemiological Investigation (PE) according to the applicable standard operating procedure, especially for transit points (seaports) and border areas, because these areas are commonly become the IMW travel point of departure and arrival, especially undocumented IMWs. The undocumented workers, so far, have been identified as a group at risk of exposure to infectious diseases. The standard operation procedure to handle the return of undocumented IMWs is actually clear and rigorous. When the ship arrived the Ministry of Marine and Fishery of the Republic Indonesia will control the completeness of the ship’s documents. After everything is complete, the seaport officer directs the passengers to get off the ship by checking their body temperature via thermal screening. To prevent transmission of disease, especially COVID-19, the Ministry of Marine and Fishery of the Republic of Indonesia remains alert to IMWs who have symptoms of coughing and influenza by conducting an antigen Rapid Test. An officer in our personal interview explains, ‘Our principle remains vigilance against the entry of infectious diseases. If we suspect of symptoms that are similar to COVID-19, then we still have antigent to see them. It takes 15 minutes to know the result, for a PCR test’. In medical term, an infectious disease is an illness caused by a biological agent (such as a virus, bacterium, or parasite) rather than by physical (such as burns) or chemical (such as poisoning). In the direct infectious disease control program, the Ministry of Marine and Fishery of Republic Indonesia carries out basic tasks and functions in limited health services, especially prevention of HIV/AIDS, STIs, TB, Leprosy and acute respiratory infections (ISPA). These five diseases are prioritised in the spread of infectious diseases coming into Indonesia.

Policy on returning process of IMWs during pre-COVID-19 pandemic

Before COVID-19 outbreaks, all the retirees or migrant workers whose working contract period was running out will receive assistance from their working agent to report their return from overseas to BP2MI before their departure from the overseas country. However, this report seems to be only recognised as a record, not being followed up by both the government through the embassy office and for BP2MI in Indonesia. So, the government and its agency can only gain the data of returning migrant workers, but not the health condition, including the potential disease carried by the workers. For the undocumented workers, there is no report process and no assistance from the working agent. The workers can go straight back to Indonesia, either by air or by sea with their own risk such as legal risk and health risk. Yet, in our observation, the health workers and/or the Ministry of Health officer who stands by in the airport and seaport did not act upon the arrival of undocumented workers. It was no inspection on medical screening, as we asked one worker who just arrived from Malaysia, who said, ‘No there isn’t an inspection. There was also no examination, no examination like that, just go home, that’s it’. This was also recognised by the coordinator of quarantine control and epidemiological surveillance in a personal interview as follow:

Yes, before COVID, we worked according to our duties and responsibilities. Our job is to prevent disease at the entrance port. So, when it comes to repatriation, we usually do related detection of such infectious disease; but it tends to be apologetic; tends to be passive. Passive in the sense of detecting the IMWs’ friends who come together with them. We screened the symptoms of the disease; then from the first detection, we put on body temperature measurement to screen those who reach above 37.5 degrees. If we found one, then we put him/her to the exercise room and we examined him/her. If there is a potential for an infectious disease, we refer the patient to the referral hospital, usually the provincial hospital.

The standard operating procedure (SOP) mentioned by the port officer is actually the procedure for the Epidemiological Investigation (PE), not for ‘biosecurity’ procedure. In accordance with the Ministerial Regulation No. 1501/MENKES/PER/X/2010 issued by the Ministry of Health, PE is a medical screening process that must be done in epidemiological surveillance for anyone who arrive into the country. In this case, this policy is only being implemented for the coming of Indonesian migrant workers from overseas in order to control the symptom of infectious diseases. Nevertheless, the Port Health Office (known as KKP) appeared to not seriously implement the border-health security to any cross-border people, especially to those returned migrant workers. Health screening and quarantine seem to be not terrifying process that must be followed by migrant workers who return back to the country. Migrant workers will feel terrified with the immigration and document screening rather than the so-called ‘biosecurity’ procedure. The Port Health Office seems only glimpsed the physical condition of those returned IMWs when they arrived at the airport or the seaport. If the officer(s) observed physically workers look normal, they consider them as if in a good health.

Perceptions of health workers regarding health and illness influence whether the conduct of medical screening need to be carried out or not. Types of diseases such as influenza, for instance, has not been perceived by the health workers in the port as communicable diseases, so it does not need a medical screening. Inconsistency implementing the medical screening procedure upon the arrival of retired IMWs could be potentially causing dangerous risk of reproducing and (re)reproducing various infectious diseases in Indonesia (Kabir et al., Citation2020).

It is not only that inconsistency conduct occurred in the port of arrival, but there is also an absent of notice or statement written on the working contract of those migrant workers, which saying that to those who retire or completing their working contract, the health screening will not be conducted to the workers arrival time in Indonesia.

This condition is different to the departure procedure. All Indonesian migrant workers are required to be examined and follow the medical screening strictly, especially to identify whether the workers are in a good health condition or having particular infectious disease, which stated on the list of overseas country in where the worker will be worked or placed. For those who are infected with a contagious disease, their departure will be cancelled

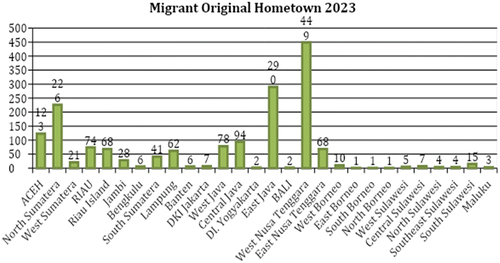

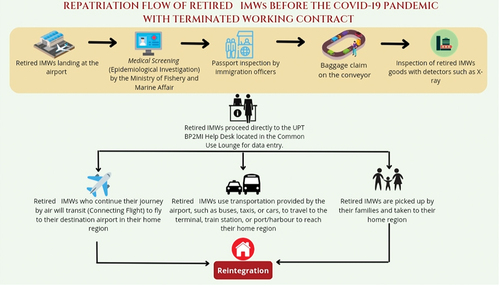

shows the procedure of arrival for returned workers from overseas after the conclusion of their job contract with their agents. This figure also shows a procedure of medical screening as the first conduct that must be followed by the workers. However, in practices, this medical screening is occasionally being applied.

Figure 3. The IMWS return flowfull duty before the COVID-19 pandemic with the contract working time expired.

According to for the worker who arrive and being infected with a communicable disease or if someone with the disease died in overseas country with the infectious disease, the procedure of returning home is more complicated. The worker or a friend or an agent should make a report to the Embassy or the Consulate General of the Republic of Indonesia in overseas country. Both the Embassy and the Consulate General have an obligation to provide protection to the worker in fully duty. The Indonesian Consulate or Embassy will make coordination with the migrant workers protection board and the migrant workers association (only for those who have a complete/legal document of citizenship and working contract) to travel the worker or the corpus body to his/her hometown in Indonesia.

If the worker remains sick, he or she must first be treated in the receiving country until it shows progress towards recovery. When worker is in the recovery process, and if he or she also experiences with psychological problem, the he/she can be returned to Indonesia, but he/she must be placed in a temporary shelter at the Repatriation House and Trauma Center (RPTC) before reintegration to the family and community.

To handle migrant workers who are detected with infectious disease, the airport authority will make coordination with other stakeholders related to migration and migrant worker such as BP2MI, the Ministry of Social Affairs, P3MI, the district/city Health Office, and NGOs before they hand over the worker to the family. The worker’s family will also be assisted by the district/city Health Office and NGOs to monitor the health condition of the worker and for continuing medical examination. It is a compulsory for the worker and the family to apply for health insurance from the government’s agency i.e. the Health Social Security Administration Agency (BPJS). The worker with the certain disease will get a cover letter from the local Social Service, and bring the letter to the health authority such as regional hospital or local health provider/clinic to carry out further treatment. If the worker does not apply the health insurance from the BPJS, then she/he will be the responsibility for the costs incurred during the hospital treatment (Habibullah et al., Citation2016; Sepriandi, Citation2018).

Policy in the process of returning retired IMWs to Indonesia during COVID-19 pandemic

According to the flow returning of IMWs to Indonesia, there is indeed data collection and health examinations up to the polyclinic. However, data collection and health examinations only concern diseases suffered during the journey from the recipient country to Indonesia. These diseases include flu/cold, diarrhoea, fatigue, dizziness, but there is no further tracing related to congenital diseases or contagious diseases while IMW is in the recipient country (Kinasih & Dugis, Citation2015). Placement and Protection of Indonesian Migrant Workers (Tjitrawati & Romadhona Citation2024) has summarised the number of sick or hospitalised Indonesian Migrant Workers (IMW) over the past five years from 2016 to December 2020, totalling 1.136 people. However, this data does not provide a clear picture of the types of diseases suffered by IMW and the level of contagiousness posed.

Figure 4. The process of repatriating retired IMW is based on head of BNP2 IMWs regulation No.Per.01/KA/Su/1/2008.

Data from the Ministry of Social Affairs of the Republic of Indonesia, Directorate General of Social Rehabilitation (2020), show that the diseases suffered by IMWs treated by RPTC until February 2020 are fever, cough, cold, tuberculosis (TB), and mental disorders. In addition, one IMW from East Nusa Tenggara died from complications of meningitis, hepatitis B, and HIV. However, this data does not show the separation data of IMW patients or not, treated by RPTC.

There is a correlation between migration and mobility in a country that has an impact on the occurrence of both epidemic and pandemic diseases (Hanefeld et al., Citation2017; McMichael, Citation2020; Sari & Augeraud-Véron, Citation2015). Migration is always accompanied by mobility in the form of moving residences from villages to cities or from one country to another (Hirsch, Citation2018; Hoffman, Citation2009; Rydzik et al., Citation2012).

Diseases caused by migration and mobility globally include Sexually Transmitted Diseases (STD) and HIV/AIDS (Castelli & Sulis, Citation2017; Herdt, Citation1997; H. Liu et al., Citation2005; Maatouk et al., Citation2020); Chickenpox/Varicella, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, HIV/AIDS, intestinal parasites, malaria, measles, polio, rubella (Tam, Citation2006); Campylobacter jejuni (Wilson et al., Citation2008); influenza A or H1N1 2009 (Nelson et al., Citation2015); Sexually Transmitted Infections (STD) including chlamydia, gonorrhoea, and syphilis (Fuchs & Brockmeyer, Citation2014; Greenaway & Castelli, Citation2019; Smith & Angarone, Citation2015; Tuddenham et al., Citation2022); malaria (Beay et al., Citation2017); SARS, MERS, malaria, schistosomiasis, west Nile, dengue, chikungunya, and tuberculosis (Colley et al., Citation2014; Jiménez-Morillas et al., Citation2019; Tian, Citation2020; Vignier & Bouchaud, Citation2018; Wu, Citation2019); measles (Beay, Citation2018; Bester, Citation2016; Perry et al., Citation2004); Hepatitis B (Thijssen et al., Citation2019); Entamoeba histolytica (El-Dib, Citation2017; Sahimin et al., Citation2019; Sierra-López et al., Citation2018); and COVID-19 (Araujo & Naimi, Citation2020; Poirier et al., Citation2020; Sajadi et al., Citation2020). Migration will create behavioural changes caused by changes in weather, types of food, types of water that have risks of disease transmission globally (Baker et al., Citation2022; Lindahl & Grace, Citation2015; Meze-Hausken, Citation2000).

In the case of the Corona Virus Disease pandemic, known as COVID-19, designated by the WHO on 11 March 2020 (Ali et al., Citation2020; Hageman, Citation2020; Mishal, Citation2020), migrant workers, in general, are highly vulnerable to the spread of the disease. In Singapore, there was an increase of 800 cases of COVID-19 among migrant workers in a day (Uly, Citation2020). Similarly, among IMW working as sailors, 4 out of 77 people tested positive for the COVID-19 virus on the Diamond Princess anchored in Yokohama, Japan (Mizumoto et al., Citation2020; Rocklöv et al., Citation2020).

Data from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs on 17 May 2020 stated that there were 17,325 Indonesian sailors working on 118 cruise ships, with 1 Indonesian sailor from the Symphony of the Seas ship dying due to COVID-19. Also, as an impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, Indonesian citizens repatriated from abroad numbered 132,978 people, of which 591 people tested positive for COVID-19. Out of the 591 positive cases, 312 were migrant workers, including sailors and students (Muliya, Citation2020). Additionally, 2 IMWs from Karawang were exposed to a new variant mutation of the SARS-CoV-2 virus B117 after returning from Saudi Arabia (Safutra, Citation2021), and IMWs working in Malaysia travelling to Batam, Riau Islands was infected with a new variant of the SARS-CoV-2 virus B1525 from Singapore (Davina, Citation2021).

Based on this data, migrant workers are at risk of being infected and carrying diseases (whether consciously or unconsciously) and have the potential to transmit these diseases back to their home areas. In other words, the parameter for the spread of contagious diseases related to migration is migrant workers (Cayuela et al., Citation2018b; Guo & Li, Citation2012; Preibisch & Hennebry, Citation2011; Wang & Wang, Citation2012).

As stated by the ILO (Citation2020b), the global number of migrant workers is approximately 2.2 billion, and Indonesia is one of the major contributors to migrant workers in the world, along with the Philippines (Al-Najjar, Citation2002; Lan, Citation2003; Lyons, Citation2006; Setyawati, Citation2013; Yeoh et al., Citation1999). Migrant workers are vulnerable to disease transmission, as seen in cases of malaria in Thailand (Kitvatanachai & Rhongbutsri, Citation2012); Zika virus in Singapore (Tam et al., Citation2016); tuberculosis in Lebanon (Fernandez, Citation2018); reproductive and sexual health in Malaysia (Lasimbang et al., Citation2016); HIV in Korea (Lee, Citation2008); malaria, enteric fever, hepatitis A and E, and tuberculosis in Singapore (Sadarangani et al., Citation2017); sexually transmitted diseases in South Florida (Sánchez, Citation2015); HIV infection in the United States (Albarrán & Nyamathi, Citation2011; Organista et al., Citation2004); anaemia, diarrhoea, colitis, diabetes, obesity, and unhealthy breath odour in the United States (Pillow Thomas Ence et al., Citation2015); COVID-19 in China (Chen et al., Citation2020; Leung et al., Citation2020; Liem et al., Citation2020); COVID-19 in Singapore (Moroz et al., Citation2020); and COVID-19 in the United States (Bergquist et al., Citation2020).

Based on previous data and studies, not much has been studied on medical screening of returning IMWs, creating health risks for themselves and becoming a source of disease transmission to their families and surrounding communities. Therefore, this study explores and analyzes returning IMWs through the perspective of Ulrich Beck, who explains the risk society. Risk society is a condition where society will face threats of disorder, ignorance, ambiguity, and uncertainty, consciously or unconsciously society will follow the process of social change to meet the demands of life that produce consequences. These consequences are risks that can threaten them at any time (Beck, Citation1992; Lash et al., Citation1994). Risk society is caused not by nature but by humans. Risk is not merely the action of the individual itself but is collectively formed and influences the individual itself (Giddens, Citation1990; Luhmann, Citation1989; Power, Citation2007).

Furthermore, this science will experience fragmentation into a policy in this case Law no. 18/2017, implementing regulations seem to be a truth, for the sake of the economic interests of the country. Science increasingly does not show scientization, which should be indispensable to, but incapable of showing truth and enlightenment. Instead, science creates risks, which in this study is the spread of contagious diseases among migrant workers. The Indonesian government does not conduct medical screening procedures for IMW when repatriating them, so IMWs along with their families and surrounding environments are vulnerable to disease transmission.

Medical screening is very necessary regarding the spread of contagious diseases because migration will create opportunities for the formation of new contagious diseases and potentially spread microorganisms globally (Soto, Citation2009). Migration and mobility cause individuals to be categorised as high-risk for disease transmission (Hanefeld et al., Citation2017). Migration and mobility have been proven to contribute to the spread of contagious diseases.

The repatriation of retired Indonesian Migrant Workers (IMW) to Indonesia during the COVID-19 pandemic is regulated in Government Regulation No. 59/2021 articles 24, 35 (f), 41, 56, 65 (d), 69, and 82, stating that the central government, provinces, and regencies/cities coordinate to facilitate the return of IMW to their respective regions while fulfilling the requirements and health protocols. Since the declaration of the COVID-19 pandemic by the WHO (Citation2020 g) until the emergence of the new COVID-19 variant B.1.1.529 Omicron, on Friday, 26 November 2021 (Sahoo & Samal, Citation2021), there have been 14 policies established by the government starting from 25 May 2020, related to medical screening until arrival in the home region. These 14 policies are as follows:

According the above, the Indonesian government has implemented policies regarding the return of retired Indonesian Migrant Workers (IMWs) during the COVID-19 pandemic. These policies are outlined in Circulars Letter (SE) and Decisions Letter (SK). The issuance of SEs and SKs reflects the government’s efforts to coordinate various governmental bodies such as the Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries, Health Offices, Transportation Offices of the Province, as well as local governments like the Surabaya City Government, in the collective endeavour to prevent and control the spread of COVID-19. In total, there are 14 SEs (Circulars Letter) and SKs (Decisions Letter) that have been issued. These documents encompass five policy regulations, which are determined based on the evolving landscape of COVID-19 variants and the prevailing situation within Indonesia. The classification of these SEs (Circulars Letter) and SKs (Decisions Letter) is structured around the following factors:

Table 2. The IMWs returning policy during pandemic of COVID-19.

COVID-19 Variants: These include variants such as B.1.1.7 (Alpha), P1 (Gamma), B.1.351 (Beta), B.1.617.2 (Delta), and B.1.1.529 (Omicron). The government’s response is tailored according to the characteristics and prevalence of these variants.

Situation in Indonesia: This refers to the broader context of the COVID-19 situation within Indonesia. It encompasses various aspects such as the adoption of new habits to mitigate the spread of the virus, preparations for significant events like Christmas 2020 and New Year 2021, as well as efforts towards national economic recovery.

By categorising the SEs (Circulars Letter) and SKs (Decisions Letter) according to these factors, the government aims to provide targeted and effective measures to address the challenges posed by COVID-19, ensuring the safety and well-being of its citizens, including IMWs, and facilitating a coordinated response across different levels of governance.

The repatriation process of the retired IMWs to Indonesia during the COVID-19 pandemic is regulated under the government regulation of PP No. 59/2021 articles 24, 35 (f), 41, 56, 65 (d), 69 and 82 which allow the Central, Provincial and District/City governments work together to facilitate the workers to their place of origin or a hometown by fulfilling health requirement test and protocols. Since the COVID-19 pandemic was declared by the WHO until the emergence of a new variant of COVID-19 B.1.1. 529 Omicron (Khandia et al., Citation2022), on Friday 26 November 2021 (Sahoo & Samal, Citation2021), there have been 14 regulations issued by the government starting on 25 May 2020, which associated with medical screening for the arrival workers to their hometown. During the COVID-19, the Government issued a Circular Letters (SE) and Decrees (SK) for health screening procedure. to preventing and controlling COVID-19 outbreaks. The development of COVID-19 variants included B.1.1.7 (Alpha), P1 (Gamma), B.1.351 (Beta), B.1.617.2 (Delta), and B.1.1.529 (Omicron), had made the Central and Regional authorities in Indonesia issued various regulations and health control protocols applied for foreigners, visitors, and migrant workers who came into the country.

A regulation (SE No. 5/2020) launched on 25 May 2020 was problematic since that regulation did not mention any medical screening procedure for returning retired IMWs in the prevention and control of COVID-19. As a result the airport and seaport authorities did not instigated this regulation to the workers as far as they looked healthy and wore a mask. Following that regulation, the government then issued other SE No. 7/2020 and SE No. 9/2020, which clearly stated the need to apply for medical screening for migrant workers. With these two regulations (SEs), the airport and seaport authorities carried out the medical screening for international travellers including returned migrant workers, and quarantine requirement for all the incoming passengers.

Another regulation issued SE No. 3/2020, on 19 December 2020, to regulate the process of repatriating retired IMWs from recipient countries to their regions of origin. Provision to do PCR swab before departure must be attached to international e-HAC, a government digital health monitoring application, until the workers received green status, then they could boarding to the vessel to Indonesia. This regulation SE No. 3/2020 was an addendum from the previous ones.

SE No. 4/2020, issued on 28 December 2020, to respond to the development of new variant of COVID-19 B.1.1.7 (Alpha) and tightening the entry gates to Indonesia, the government restricted the entry ports for International travellers only in Jakarta, then the travellers must screen the health test and been quarantined for a week before travel to other regional/domestic areas. From the regional town/city, the migrant workers needed to do another test and quarantined provided by the provincial government in their hometown. The port authorities, in this situation, were use regulation of the Ministry of Health in 2010 together with the regional’s policy on COVID-19 handling protocol. During the implementation of these regulation on COVID-19, many migrant workers did not understand, and even some of them had provided false and fake PCR test documents. Those workers did not mean to provide a fake health certificate. They stated that they received the certificate from their employer, so they thought the certificate is valid.

[H]ow do you in-swab, some of those we asked were confused and answered they didn’t know. They can’t explain what the process is like, that means the PCR certificate is fake. They said they didn’t know this sheet, I was given it by the employer, they said they used it home So, it was falsified from several labs, mostly workers came from Malaysia and Singapore.” […] How we know that the certificate was fake, the workers don’t know the pick up swab procedure. Sometimes our statement traps him when he examines how his blood is drawn here [by pointing elbow fold (popliteal)], or here [by pointing wrist (radial)]? Well he hesitantly answered taken here [by pointing elbow fold (popliteal)]. So from there it means he didn’t do the process swab. We deliberately do not ask here whether he was poked by the nose or not. Later they find out, they can see it from social media. (Port officer in a personal interview)

Certificate of PCR issued by health authorities in Malaysia and Singapore was very difficult to prove whether it was fake or not, but what it was clear that retired IMWs have never performed PCR test before returning to Indonesia.

Ability to communicate regarding self-quarantine in the area of origin and results exit test in districts/cities all should be done by the stakeholder both at the central and regional government levels. Management risk communication is essential for the management of health emergencies (Zhang et al., Citation2020). Effective process in preventing and controlling the spread of COVID-19 by the migrant workers was crucial and could causing more risk for the larger society in the hometown of the workers.

The entire communication process must integrate the accessibility and disclosure of risk information, the frequency of communication, and the strategy that must be carried out. Objective risk communication management is to make policies in planning and implementing in the context of prevention and spread of COVID-19 (Rachmah, Citation2024; Zhang et al., Citation2020). The central government is a key actor in risk communication management to make appropriate policy regulations in the prevention and control of COVID-19 (Hajek, Citation2021).

Health quarantine is a process of self-isolation with the aim of preventing the risk of transmission of COVID-19 and marking early whether infected with COVID-19 or not (Amir, Citation2022). Quarantine is needed as an effort to isolate individuals who are healthy or not infected COVID-19, but has a history of contact with someone who has confirmed COVID-19 or a history of travel to areas that have local transmission. Quarantine room should be a single room and must have ventilation and facility adequate bathroom, kitchen and living room. If these requirements does not meet, one person can have more than one person in one room, as long as they do physical distancing at least 1 metre between all quarantined persons (Hou et al., Citation2020; Peak et al., Citation2020).

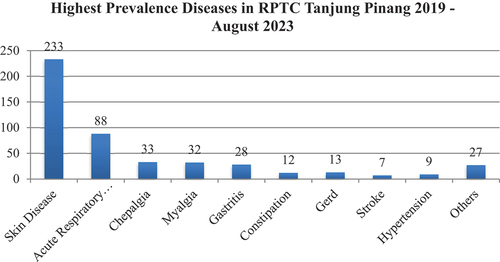

With these two reasons, the government’s choice to carry out an 8-day quarantine, refer to the following diagram 9 see ).

Information:

The light blue colour indicates the risk of transmissionpost quarantine daily and no symptoms of COVID-19 infection were produced during daily symptom monitoring

The dark blue colour indicates the risk of transmissionpost quarantine with added resultsswab negative PCR.

Following the quarantine can end on the 10th day for nothing swab PCR was negative and no symptoms were reported during monitoring daily. This option, the risk of post-quarantine transmission is estimated at 1% to 10%. This option to shorten the quarantine as an acceptable alternative, although this quarantine is less effective than the 14 days as recommended by WHO and CDC. Especially with the issuance of SE (Circulate Letter) No. 20/2021, on the grounds of national economic recovery, the quarantine period only lasts 5 days.

These two reasons actually create risks that are certainly harmful, threatening, and expand the spread of COVID-19, either IMW retirees themselves and their families in their area of origin, even to all regions Indonesia in general. According to Beck, this is called a risk position that awareness (consciousness) determines its presence (being) (Beck, Citation1992). Every individual is aware of this risk because policy makers regarding the quarantine process which is determined to be only 8 days contradicts WHO standard provisions (WHO, Citation2020b), and CDC (Jernigan et al., Citation2020) regarding the quarantine process which should be carried out for 14 days, due to the high cost of quarantine. This will create a risk of spreading COVID-19 in Indonesia, regardless of class position.

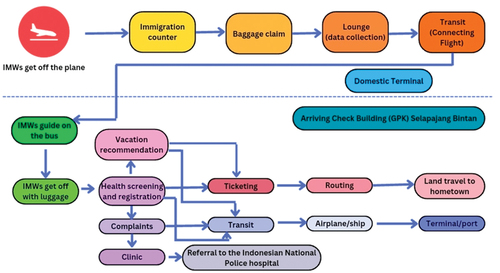

The flow of IMWs repatriation during the COVID-19 Pandemic can be described as follows.

Based on above, health workers in receiving countries reconsider the COVID-19 pandemic situation, that the certificate swab PCR they can manipulate (Beck, Citation1992; Boström et al., Citation2017). Migrant workers are the last group with or without access to health services, including giving a statement swab PCR, as well as recipient countries, do not guarantee protection for migrant workers during the COVID-19 pandemic (Liem et al., Citation2020; W. Liu et al., Citation2014; WHO, Citation2020a). The consequences will be reproduce and (re)reproduction infectious diseases in the sending country.

Conclusion

The conclusion of this research is the inadequate implementation of health screening procedures for returning migrant workers, particularly retired Indonesian Migrant Workers (IMWs), posing significant risks to both domestic and global health security. Despite regulations and policies aimed at preventing the spread of infectious diseases, inconsistencies in enforcing medical screening protocols, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, have been observed. This inconsistency, coupled with the challenges of verifying the authenticity of health certificates and the shortened quarantine periods, increases the likelihood of disease transmission within Indonesia and beyond. The lack of rigorous health surveillance at ports of entry and departure exacerbates these risks, particularly for undocumented workers who may bypass screening altogether. Addressing these shortcomings requires coordinated efforts among governmental bodies, health authorities, and international organisations to ensure the effective implementation of health protocols, robust risk communication strategies, and equitable access to healthcare services for all migrant workers. Failure to do so not only jeopardises the health and well-being of returning workers and their communities but also undermines efforts to control the spread of infectious diseases on a global scale.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article was originally published with errors, which have now been corrected in the online version. Please see Correction (https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/23779497.2024.2366550)

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Irfan Wahyudi

Irfan Wahyudi, S. Sos, M.Comm., Ph.D is a Associate Professor at the Department of Communication Universitas Airlangga, his research interest mainly concerning on Migration and media, identity & gender, Community media, Internet studies. The author can be contacted via email [email protected]

Sri Endah Kinasih

Dr. Sri Endah Kinasih, S.Sos., M.Si is a Associate Professor at the Department of Anthropology Universitas Airlangga, her research interest mainly concerning on legal anthropology an migration study, she also the leading of Global Migration Research Group, Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Universitas Airlangga. The author can be contacted via email [email protected]

Rachmah Ida

Prof. Dra. Rachmah Ida, M.Comm., Ph.D is a Professor at the Department of Communication Universitas Airlangga, her research interest mainly concerning on Media, gender, islam, pop culture, women. The author can be contacted via email [email protected]

Toetik Koesbardiati

Prof. Dr.phill. Toetik Koesbardiati, Dra is a Professor at the Department of Anthropology Universitas Airlangga her research interest mainly concerning on Paleoanthropology, Bioarchaeology, and History and Spread of Diseases (esp. NTD’s). The author can be contacted via email [email protected]

Mochamad Kevin Romadhona

Mochamad Kevin Romadhona, S.Sosio is a Research Assistant at the Global Migration Research Group, Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Universitas Airlangga, his research interest mainly concerning on Migration and Sociology of Health. The author can be contacted via email [email protected] or [email protected]

Seokkyu Kim

Seokkyu Kim, is currently student at School of Arts and Culture Yong In University his research interest mainly concerning on Southeast Asia study. The author can be contacted via email [email protected]

References

- Albarrán, C. R., & Nyamathi, A. (2011). HIV and Mexican migrant workers in the United States: A review applying the vulnerable populations conceptual model. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 22(3), 173–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jana.2010.08.001

- Ali, M. G., Ahmad, M. O., & Husain, S. N. (2020). Spread of corona virus disease (COVID-19) from an outbreak to pandemic in the year 2020. Asian Journal of Research in Infectious Diseases, 37–51. https://doi.org/10.9734/ajrid/2020/v3i430135

- Al-Najjar, S. (2002). Women migrant domestic workers in Bahrain. International migration papers. htt ps://do i.org/9221132439

- Amir, H. (2022). Strategies in preventing the transmission of COVID-19 a quarantine, isolation, lockdown, tracing, testing and treatment (3t): Literature review. Asia Pacific Journal of Health Management, 17(2), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.24083/apjhm.v17i2.1465

- Araujo, M. B., & Naimi, B. (2020). Spread of SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus likely to be constrained by climate. BMJ Yale, 2003–2020. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.12.20034728.

- Baker, R. E., Mahmud, A. S., Miller, I. F., Rajeev, M., Rasambainarivo, F., Rice, B. L., Takahashi, S., Tatem, A. J., Wagner, C. E., Wang, L.-F., Wesolowski, A., & Metcalf, C. J. E. (2022). Infectious disease in an era of global change. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 20(4), 193–205. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-021-00639-z

- Beay, L. K. (2018). Dinamika penyebaran campak dengan pengaruh migrasi. Jurnal Sainsmat, 7(2), 125. https://doi.org/10.35580/sainsmat7273652018

- Beay, L. K., Kasbawati, K., & Toaha, S. (2017, 1). Effects of human and mosquito migrations on the dynamical behavior of the spread of malaria. AIP Conference Proceedings, 1825.

- Beck, U. (1992). Risk society: Towards a new modernity (1st ed.). SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Bergquist, S., Otten, T., & Sarich, N. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Health Policy and Technology, 9(4), 623–638. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hlpt.2020.08.007

- Bester, J. C. (2016). Measles and measles vaccination: A review. JAMA Pediatrics, 170(12), 1209–1215. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.1787

- Boström, M., Lidskog, R., & Uggla, Y. (2017). A reflexive look at reflexivity in environmental sociology. Environmental Sociology, 3(1), 6–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/23251042.2016.1237336

- BP2MI. (2022). Data Penempatan dan Pelindungan PMI Periode Tahun 2022.

- Castelli, F., & Sulis, G. (2017). Migration and infectious diseases. Clinical Microbiology and Infection, 23(5), 283–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2017.03.012

- Cayuela, A., Martínez, J. M., Ronda, E., Delclos, G. L., & Conway, S. (2018a). Assessing the influence of working hours on general health by migrant status and family structure: The case of Ecuadorian-, Colombian-, and Spanish-born workers in Spain. Public Health, 163, 27–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2018.06.013

- Cayuela, A., Martínez, J. M., Ronda, E., Delclos, G. L., & Conway, S. (2018b). Assessing the influence of working hours on general health by migrant status and family structure: The case of Ecuadorian-, Colombian-, and Spanish-born workers in Spain. Public Health, 163, 27–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2018.06.013

- Chakraborty, I., & Maity, P. (2020). COVID-19 outbreak: Migration, effects on society, global environment and prevention. Science of the Total Environment, 728, 138882. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138882

- Chen, Z.-L., Zhang, Q., Lu, Y., Guo, Z.-M., Zhang, X., Zhang, W.-J., Guo, C., Liao, C.-H., Li, Q.-L., & Han, X.-H. (2020). Distribution of the COVID-19 epidemic and correlation with population emigration from Wuhan, China. Chinese Medical Journal, 133(9), 1044–1050. https://doi.org/10.1097/CM9.0000000000000782

- Cicero, A. (2019). Southeast Asia strategic multilateral dialogue on biosecurity. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 25(5).

- Colley, D. G., Bustinduy, A. L., Secor, W. E., & King, C. H. (2014). Human schistosomiasis. The Lancet, 383(9936), 2253–2264. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61949-2

- Davina. (2021). Temuan Mutasi Virus Corona Baru B1525, Apakah Vaksin yang Ada Akan Tetap Efektif?. Kompas. https://www.kompas.tv/article/165662/temuan-mutasi-virus-corona-baru-b161525-apakah-vaksin-yang-ada-akan-tetap-efektif

- Dewanti, L., Sulistiawati, S., & Nuswantoro, D. (2021). TOT Penyakit Menular Pada Satgas WNI Migran Terdeportasi Di Tanjung Pinang. Jurnal KARINOV, 4(2), 82–87.

- El-Dib, N. A. (2017). Entamoeba histolytica: An overview. Current Tropical Medicine Reports, 4(1), 11–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40475-017-0100-z

- Fauzi, M. A., & Paiman, N. (2021). COVID-19 pandemic in Southeast Asia: Intervention and mitigation efforts. Asian Education and Development Studies, 10(2), 176–184. https://doi.org/10.1108/AEDS-04-2020-0064

- Fernandez, B. (2018). Health inequities faced by Ethiopian migrant domestic workers in Lebanon. Health & Place, 50, 154–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2018.01.008

- Fuchs, W., & Brockmeyer, N. H. (2014). Sexually transmitted infections. JDDG: Journal der Deutschen Dermatologischen Gesellschaft, 12(6), 451–464. https://doi.org/10.1111/ddg.12310

- Gangurde, H. H., Gulecha, V. S., Borkar, V. S., Mahajan, M. S., Khandare, R. A., & Mundada, A. S. (2011). Swine influenza a (H1N1 virus): A pandemic disease. Systematic Reviews in Pharmacy, 2(2), 110. https://doi.org/10.4103/0975-8453.86300

- Gelatt, J. (2020). Immigrant workers: Vital to the US COVID-19 response, disproportionately vulnerable. Migration Policy Institute, 26.

- Giddens, A. (1990). The consequences of modernity. Stanford University Press. http://www.sup.org/books/title/?id=2664

- Greenaway, C., & Castelli, F. (2019). Infectious diseases at different stages of migration: An expert review. Journal of Travel Medicine, 26(2), taz007. https://doi.org/10.1093/jtm/taz007

- Guo, H., & Li, M. Y. (2012). Impacts of migration and immigration on disease transmission dynamics in heterogeneous populations. Discrete and Continuous Dynamical Systems - Series B, 17(7), 2413–2430. https://doi.org/10.3934/dcdsb.2012.17.2413

- Habibullah, N. F. N., Juhari, A., & Sandra, L. (2016). Kebijakan Perlindungan Sosial Untuk Pekerja Migran Bermasalah. Sosio Konsepsia, 5(2), 66–67. https://doi.org/10.33007/ska.v5i2.178

- Hageman, J. R. (2020). The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Pediatric Annals, 49(3). https://doi.org/10.3928/19382359-20200219-01

- Hajek, A. (2021). “Determinants of postponed cancer screening during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from the nationally representative COVID-19 snapshot monitoring in Germany (COSMO).” Risk Management and Healthcare Policy , 3003–3011.

- Hanefeld, J., Vearey, J., Lunt, N., Bell, S., Blanchet, K., Duclos, D., Ghilardi, L., Horsfall, D., Howard, N., Adams, J. H., Kamndaya, M., Lynch, C., Makandwa, T., McGrath, N., Modesinyane, M., O’Donnell, K., Siriwardhana, C., Smith, R. … Wickramage, K. P. (2017). A global research agenda on migration, mobility, and health. The Lancet, 389(10087), 2358–2359. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31588-X

- Herdt, G. (1997). Sexual cultures and migration in the era of AIDS: Anthropological and demographic perspectives. Clarendon Press.

- Hirsch, E. (2018). Remapping the vertical archipelago: Mobility, migration, and the everyday labor of Andean development. The Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Anthropology, 23(1), 189–208. https://doi.org/10.1111/jlca.12260

- Hoffman, D. M. (2009). Changing academic mobility patterns and international migration: What will academic mobility mean in the 21st century? Journal of Studies in International Education, 13(3), 347–364. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315308321374

- Hollweck, T. (2015). Robert, K. Y. ( 2014). Case study research design and methods. In The Canadian journal of program evaluation (5th ed. p. 282). Sage. https://doi.org/10.3138/cjpe.30.1.108

- Hou, C., Chen, J., Zhou, Y., Hua, L., Yuan, J., He, S., Guo, Y., Zhang, S., Jia, Q., Zhao, C., Zhang, J., Xu, G., & Jia, E. (2020). The effectiveness of quarantine of Wuhan city against the corona virus disease 2019 (COVID‐19): A well‐mixed SEIR model analysis. Journal of Medical Virology, 92(7), 841–848. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.25827

- Ilo, L. M. B. (2015). ILO global estimates on migrant workers: Results and methodology. International Labour Organisation (ILO).

- Jernigan, D. B., Covid, C. D. C., & Team, R. (2020). Update: Public health response to the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak—United States, February 24, 2020. Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Report, 69(8), 216. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6908e1

- Jiménez-Morillas, F., Gil-Mosquera, M., & García-Lamberechts, E. J. (2019). Fever in travellers returning from the tropics. Medicina Clínica (English Edition), 153(5), 205–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medcle.2019.03.013

- Kabir, H., Fatema, S. R., Hoque, S., Ara, J., & Maple, M. (2020). Risks of HIV/AIDS transmission: A study on the perceptions of the wives of migrant workers of Bangladesh. Journal of International Women’s Studies, 21(6), 450–471.

- Kaner, J., & Schaack, S. (2016). Understanding ebola: The 2014 epidemic. Globalization and Health, 12(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-016-0194-4

- Khandia, R., Singhal, S., Alqahtani, T., Kamal, M. A., Nahed, A., Nainu, F., Desingu, P. A., & Dhama, K. (2022). Emergence of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron (B. 1.1. 529) variant, salient features, high global health concerns and strategies to counter it amid ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Environmental Research, 209, 112816. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2022.112816

- Kinasih, S. E., & Dugis, V. M. A. (2015). Perlindungan Buruh Migran Indonesia melalui Deteksi Dini HIV/AIDS pada saat reintegrasi ke daerah asal. Masyarakat, Kebudayaan Dan Politik, 28(4), 198–210. https://doi.org/10.20473/mkp.V28I42015.198-210

- Kitvatanachai, S., & Rhongbutsri, P. (2012). Malaria in asymptomatic migrant workers and symptomatic patients in Thamaka District, Kanchanaburi Province, Thailand. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Disease, 2, S374–S377. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2222-1808(12)60184-4

- Kõu, A., & Bailey, A. (2014). ‘Movement is a constant feature in my life’: Contextualising migration processes of highly skilled Indians. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 52, 113–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2014.01.002

- Kõu, A., van Wissen, L., van Dijk, J., & Bailey, A. (2015). A life course approach to high-skilled migration: Lived experiences of indians in the Netherlands. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 41(10), 1644–1663. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2015.1019843

- Lan, P.-C. (2003). Political and social geography of marginal insiders: Migrant domestic workers in Taiwan. Asian and Pacific Migration Journal, 12(1–2), 99–125. https://doi.org/10.1177/011719680301200105

- Lash, S., Beck, U., & Giddens, A. (1994). Reflexive modernization: Politics, tradition and aesthetics in the modern social order. Stanford University Press. http://www.sup.org/books/title/?id=2440

- Lasimbang, H. B., Tong, W. T., & Low, W. Y. (2016). Migrant workers in Sabah, East Malaysia: The importance of legislation and policy to uphold equity on sexual and reproductive health and rights. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 32, 113–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2015.08.015

- Lee, J. (2008). Migrant workers and HIV vulnerability in Korea. International Migration, 46(3), 217–233. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2435.2008.00467.x

- Leung, K., Wu, J. T., Liu, D., & Leung, G. M. (2020). First-wave COVID-19 transmissibility and severity in China outside Hubei after control measures, and second-wave scenario planning: A modelling impact assessment. The Lancet, 395(10233), 1382–1393. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30746-7

- Liem, A., Wang, C., Wariyanti, Y., Latkin, C. A., & Hall, B. J. (2020). The neglected health of international migrant workers in the COVID-19 epidemic. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(4), e20. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30076-6

- Lindahl, J. F., & Grace, D. (2015). The consequences of human actions on risks for infectious diseases: A review. Infection Ecology & Epidemiology, 5(1), 30048. https://doi.org/10.3402/iee.v5.30048

- Liu, W., Li, Y., Shaw, K. S., Learn, G. H., Plenderleith, L. J., Malenke, J. A., Sundararaman, S. A., Ramirez, M. A., Crystal, P. A., Smith, A. G., Bibollet-Ruche, F., Ayouba, A., Locatelli, S., Esteban, A., Mouacha, F., Guichet, E., Butel, C., Ahuka-Mundeke, S. … Hahn, B. H. (2014). African origin of the malaria parasite Plasmodium vivax. Nature Communications, 5(1), 3346. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms4346

- Liu, H., Li, X., Stanton, B., Liu, H., Liang, G., Chen, X., Yang, H., & Hong, Y. (2005). Risk factors for sexually transmitted disease among rural-to-urban migrants in China: Implications for HIV/sexually transmitted disease prevention. AIDS Patient Care & STDs, 19(1), 49–57. https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2005.19.49

- Luhmann, N. (1989). Ecological communication. University of Chicago Press.

- Lyons, L. (2006). The limits of transnational activism: Organizing for migrant workers rights in Malaysia and Singapore. University of Montreal.

- Maatouk, I., Cristaudo, A., & Morrone, A. (2020). Sexually transmitted infections and migration. Skin Disorders in Migrants, 129–137.

- Mahendradhata, Y., Ahmad, R. A., Lazuardi, L., Wilastonegoro, N. N., Meyanti, F., & Sebong, P. H. (2021). Kesehatan Global. UGM Press.

- McMichael, C. (2020). Human mobility, climate change, and health: Unpacking the connections. The Lancet Planetary Health, 4(6), e217–e218. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(20)30125-X

- Merianos, A., & Peiris, M. (2005). International health regulations. Lancet, 366(9493), 1249–1251. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67508-3

- Meze-Hausken, E. (2000). Migration caused by climate change: How vulnerable are people inn dryland areas? Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change, 5(4), 379–406. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026570529614

- Mishal, A. (2020). A review of corona virus disease-2019. Journal of Medical Science and Clinical Research, 08(7). https://doi.org/10.18535/jmscr/v8i7.59

- Mizumoto, K., Kagaya, K., Zarebski, A., & Chowell, G. (2020). Estimating the asymptomatic proportion of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) cases on board the diamond princess cruise ship, Yokohama, Japan, 2020. Eurosurveillance, 25(10). https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.10.2000180

- Moroz, H., Shrestha, M., & Testaverde, M. (2020). Potential responses to the COVID-19 outbreak in support of migrant workers. World Bank.

- Mudita, I. W. (2013). Community biosecurity in West Timor, Indonesia: The role of local communities and governments in managing huanglongbing and other diseases and pests of citrus. Charles Darwin University (Australia).

- Muliya. (2020). Tiba di Jakarta dan Bali, 591 WNI dari Luar Negeri Positif Covid-19. Kompas. https://www.kompas.tv/article/81782/tiba-di-jakarta-dan-bali-81591-wni-dari-luar-negeri-positif-covid-81719?page=all

- Nelson, M. I., Viboud, C., Vincent, A. L., Culhane, M. R., Detmer, S. E., Wentworth, D. E., Rambaut, A., Suchard, M. A., Holmes, E. C., & Lemey, P. (2015). Global migration of influenza a viruses in swine. Nature Communications, 6(1), 6696. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms7696

- Organista, K. C., Carrillo, H., & Ayala, G. (2004). HIV prevention with Mexican migrants: Review, critique, and recommendations. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 37(Supplement 4), S227–S239. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.qai.0000141250.08475.91

- Peak, C. M., Kahn, R., Grad, Y. H., Childs, L. M., Li, R., Lipsitch, M., & Buckee, C. O. (2020). Individual quarantine versus active monitoring of contacts for the mitigation of COVID-19: A modelling study. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 20(9), 1025–1033. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30361-3

- Perry, R. T., Halsey, N. A., & Orenstein, W. A. (2004). The clinical significance of measles: A review. The Journal of Infectious Diseases, 189(Supplement_1), S4–S16. https://doi.org/10.1086/377712

- Pillow Thomas Ence, M. T., Divronas, T., Peacock, F., & Kuo, D. (2015). Illness severity among non-english, non-Spanish speaking patients in a public emergency department. Academic Emergency Medicine, 22(5), S182. https://www.embase.com/search/results?subaction=viewrecord&id=L71879065&from=export%0A10.1111/acem.12644

- Poirier, C., Luo, W., Majumder, M. S., Liu, D., Mandl, K. D., Mooring, T. A., & Santillana, M. (2020). The role of environmental factors on transmission rates of the COVID-19 outbreak: An initial assessment in two spatial scales. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 17002. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-74089-7

- Power, M. (2007). Die Erfindung operativer Risiken BT. In A. Mennicken & H. Vollmer (Eds.), Zahlenwerk: Kalkulation, Organisation und Gesellschaft (pp. 123–142). VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-531-90449-8_7

- Preibisch, K., & Hennebry, J. (2011). Temporary migration, chronic effects: The health of international migrant workers in Canada. Cmaj, 183(9), 1033–1038. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.090736

- Qiu, J., Shen, B., Zhao, M., Wang, Z., Xie, B., & Xu, Y. (2020). A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: Implications and policy recommendations. General Psychiatry, 33(2), e100213. https://doi.org/10.1136/gpsych-2020-100213

- Rachmah. (2024). Socio-cultural values in managing risk communication during the COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia. Cogent Social Sciences, 10(1), 2287288.

- Rocklöv, J., Sjödin, H., & Wilder-Smith, A. (2020). COVID-19 outbreak on the diamond princess cruise ship: Estimating the epidemic potential and effectiveness of public health countermeasures. Journal of Travel Medicine, 27(3). https://doi.org/10.1093/jtm/taaa030

- Rydzik, A., Pritchard, A., Morgan, N., & Sedgley, D. (2012). Mobility, migration and hospitality employment: Voices of central and Eastern European women. Hospitality & Society, 2(2), 137–157. https://doi.org/10.1386/hosp.2.2.137_1

- Sadarangani, S. P., Lim, P. L., & Vasoo, S. (2017). Infectious diseases and migrant worker health in Singapore: A receiving country’s perspective. Journal of Travel Medicine, 24(4), tax014. https://doi.org/10.1093/jtm/tax014

- Safutra, I. (2021). 14 Mar Virus B117 Timpa 2 Pekerja Migran Asal Karawang, Keluarga Diisolasi. Jawa Pos. https://www.jawapos.com/nasional/04/03/2021/virus-b2117-timpa-2022-pekerja-migran-asal-karawang-keluarga-diisolasi/?page=all

- Sahimin, N., Yunus, M. H., Douadi, B., Yvonne Lim, A. L., Noordin, R., Behnke, J. M., Mohd Zain, S. N. (2019). Entamoeba infections and associated risk factors among migrant workers in Peninsular Malaysia, Tropical Biomedicine, 36(4), 1014–1026.

- Sahoo, J. P., & Samal, K. C. (2021). World on alert: WHO designated South African new COVID strain (Omicron/B. 1.1. 529) as a variant of concern. Biotica Research Today, 3(11), 1086–1088.

- Sajadi, M. M., Habibzadeh, P., Vintzileos, A., Shokouhi, S., Miralles-Wilhelm, F., & Amoroso, A. (2020). Temperature, humidity, and latitude analysis to predict potential spread and seasonality for COVID-19. Social Science Research Network. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3550308

- Sánchez, J. (2015). Alcohol use among Latino migrant workers in South Florida. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 151, 241–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.03.025

- Sari, N., & Augeraud-Véron, E. (2015). Periodic orbits of a seasonal SIS epidemic model with migration. Journal of Mathematical Analysis and Applications, 423(2), 1849–1866. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmaa.2014.10.084

- Sepriandi, S. (2018). Kebijakan Perlindungan Sosial Bagi Pekerja Migran Bermasalah (PMB) di Debarkasi Kota Tanjung Pinang. KEMUDI: Jurnal Ilmu Pemerintahan, 2(2), 79–103.

- Setyawati, D. (2013). Assets or commodities? Comparing regulations of placement and protection of migrant workers in Indonesia and the Philippines. ASEAS - Austrian Journal of South-East Asian Studies, 6(2). https://doi.org/10.4232/10.ASEAS-6.2-3

- Sierra-López, F., Baylón-Pacheco, L., Espíritu-Gordillo, P., Lagunes-Guillén, A., Chávez-Munguía, B., & Rosales-Encina, J. L. (2018). Influence of micropatterned grill lines on entamoeba histolytica trophozoites morphology and migration. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, 8, 295. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2018.00295

- Sikkema, R. S., Farag, E., Islam, M., Atta, M., Reusken, C., Al-Hajri, M. M., & Koopmans, M. P. G. (2019). Global status of middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus in dromedary camels: A systematic review. Epidemiology & Infection, 147, e84. https://doi.org/10.1017/S095026881800345X

- Smith, L., & Angarone, M. P. (2015). Sexually transmitted infections. Urologic Clinics of North America, 42(4), 507–518. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ucl.2015.06.004

- Soto, S. M. (2009). Human migration and infectious diseases. Clinical Microbiology and Infection, 15, 26–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-0691.2008.02694.x

- Tam, C. C. (2006). Migration and health: Fact, fiction, art, politics. Emerging Themes in Epidemiology, 3(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-7622-3-15

- Tam, C. C., Khan, M. S., & Legido-Quigley, H. (2016). Where economics and epidemics collide: Migrant workers and emerging infections. The Lancet, 388(10052), 1374–1376. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31645-2

- Thijssen, M., Lemey, P., Amini-Bavil-Olyaee, S., Dellicour, S., Alavian, S. M., Tacke, F., Verslype, C., Nevens, F., & Pourkarim, M. R. (2019). Mass migration to Europe: An opportunity for elimination of hepatitis B virus? The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 4(4), 315–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30014-7

- Tian, D. (2020). Bibliometric analysis of pathogenic organisms. Biosafety and Health, 2(2), 95–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bsheal.2020.05.004

- Tjitrawati, A. T., & Romadhona, M. K. (2024). Living beyond borders: The international legal framework to protecting rights to health of Indonesian illegal migrant workers in Malaysia. International Journal of Migration, Health and Social Care, 20(2), 227–245. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJMHSC-04-2023-0038

- Tuddenham, S., Hamill, M. M., & Ghanem, K. G. (2022). Diagnosis and treatment of sexually transmitted infections: A review. Jama, 327(2), 161–172. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.23487

- Uly. (2020). Kenapa Pasien COVID-19 Menginfeksi Banyak Orang dan Ada yang Tidak? Kompas. https://www.kompas.com/sains/read/2020/2005/2025/120008823/kenapa-pasien-covid-120008819-menginfeksi-banyak-orang-dan-ada-yang-tidak

- Vignier, N., & Bouchaud, O. (2018). Travel, migration and emerging infectious diseases. EJIFCC, 29(3), 175.

- Wang, L., & Wang, X. (2012). Influence of temporary migration on the transmission of infectious diseases in a migrants’ home village. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 300, 100–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtbi.2012.01.004

- Warren, A. (2013). (Re) locating the border: Pre-entry tuberculosis (TB) screening of migrants to the UK. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 48, 156–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2013.04.024

- Webster, R. G., Guan, Y., Poon, L., Krauss, S., Webby, R., Govorkova, E., & Peiris, M. (2005). The spread of the H5N1 bird flu epidemic in Asia in 2004. In Peters, Clarence James, and Charles H. Calisher (Eds.), Infectious Diseases from Nature: Mechanisms of Viral Emergence and Persistence (Vol. 19, pp. 117–129).

- WHO. (2020a). ApartTogether survey: Preliminary overview of refugees and migrants self-reported impact of Covid-19.

- WHO. (2020b). Considerations for quarantine of individuals in the context of containment for coronavirus disease (COVID-19): Interim guidance.

- Wilson, D. J., Gabriel, E., Leatherbarrow, A. J. H., Cheesbrough, J., Gee, S., Bolton, E., Fox, A., Fearnhead, P., Hart, C. A., Diggle, P. J., & Guttman, D. S. (2008). Tracing the source of campylobacteriosis. PLOS Genetics, 4(9), e1000203. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1000203

- World Health Organization. (2008). International health regulations (2005).

- World Health Organization. (2020). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): Situation report.

- Wu, H. M. (2019). Evaluation of the sick returned traveler. Seminars in Diagnostic Pathology, 36(3), 197–202. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.semdp.2019.04.014

- Yeoh, B. S. A., Huang, S., & Gonzalez, J. (1999). Migrant female domestic workers: Debating the economic, social and political impacts in Singapore. International Migration Review, 33(1), 114–136. https://doi.org/10.1177/019791839903300105

- Zhang, L., Li, H., & Chen, K. (2020). Effective risk communication for public health emergency: Reflection on the COVID-19 (2019-nCoV) outbreak in Wuhan, China. Healthcare, 8(1), 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8010064

- Zhou, G., & Yan, G. (2003). Severe acute respiratory syndrome epidemic in Asia. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 9(12), 1608–1610. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid0912.030382

- Zika, V., Luz, K., Parreira, R., & Ferrinho, P. (2015). Vírus Zika: Revisão para Clínicos. Acta medica portuguesa, 28(6), 760–765. https://doi.org/10.20344/amp.6929