ABSTRACT

Distancing requirements due to the pandemic have halted many in-person therapeutic programs, including cognitive behavior therapy (CBT), increasing the likelihood that autistic children with mental health problems will struggle without adequate access to evidence-based care. Policies meant to limit the spread of COVID-19 have inadvertently exacerbated the difficulties experienced by autistic children and further exposed them to vulnerabilities that will impact their mental health. In response, interventions have been adapted for remote delivery. There is limited evidence of the acceptability, feasibility, and clinical utility for treating mental health challenges in autistic children through an online medium, within the context of a pandemic. The current study used an explanatory sequential mixed methods design to assess parents’ experience as they participated in an adapted manualized CBT program (Secret Agent Society: Operation Regulation, SAS:OR; Beaumont, Citation2013) with their autistic child. Parents reported child-related behavioral changes in pre- and post-program surveys, and both parents and therapists were interviewed about their experience through the program. The quantitative findings suggest that children learned new emotion regulation through online participation, and parents were satisfied with the program. The qualitative data supported the quantitative findings and provided new insight into factors that facilitated child engagement or made participation challenging. Overall, the findings suggest that adapted online CBT programs for autistic children can have clinical utility, and further research is needed to determine their efficacy.

Introduction

AutisticFootnote1 children and youth often experience difficulties with emotion regulation and are highly susceptible to mental health problems. Between 40–70% of children are estimated to have clinically significant levels of emotional difficulties, such as anxiety, depression, or anger (Totsika et al., Citation2011). They are also found to have higher rates of internalizing and externalizing behaviors (Eisenberg et al., Citation2001; Vaillancourt et al., Citation2017) and psychiatric diagnoses, including anxiety disorders, depression, or conduct-related disorders (Lai et al., Citation2019). These difficulties are highly interrelated (Simonoff et al., Citation2008), leading many to suggest that underlying “transdiagnostic” difficulties with emotion regulation may be important mechanisms of change (Mazefsky et al., Citation2013; Weiss, Citation2014). Systematic reviews indicate considerable support for emotion regulation as a transdiagnostic treatment construct across conditions in non-autistic adults (Sloan et al., Citation2017) and children (Moltrecht et al., Citation2020).

Mental health problems are more prevalent than before the pandemic for children, as a result of the COVID-19 state of emergency (Fegert et al., Citation2020; Torales et al., Citation2020). Distancing requirements have interrupted many in-person social, education, and therapeutic programs (e.g., interventions, day programs, schools, adapted recreation and leisure). Reports have emerged that point to the increased incidence of emotional and behavioral challenges in autistic children (Liu et al., Citation2020), including parent-reported rates of child anxiety, sadness, aggression, hyperactivity, and self-injurious behaviors (Mutluer et al., Citation2020). Abrupt changes in routines, limited access to services and schools, and changing family dynamics (i.e., loss of job, financial strain) provide an environment that further exacerbates the emergence of emotional and behavioral challenges (Lee et al., Citation2020). Importantly, children with mental health problems, including autistic children, will likely struggle even more than usual to access evidence-based care, including CBT.

In response to the pandemic, some autism service providers have adapted their interventions for online delivery, though to date, no peer-reviewed evaluations of these adapted initiatives exist (Lee et al., Citation2020). Past research suggests that virtual or remote delivery of interventions for autistic children may be feasible and helpful (Furgeson et al., Citation2019; Peterson et al., Citation2017). For example, in a randomized controlled trial, Beaumont et al. (Citation2021) found greater improvements in parent reports of child problem behaviors when child-parent dyads participated in a set of social skills-based computer game activities (found within the Secret Agent Society), compared to when dyads play nonsocial skills cognitive training computer games. In both conditions, parents received an initial training to use the games, and weekly guided self-help check-ins from a therapist over the telephone or computer to troubleshoot the computer activities. Pre-pandemic research with autistic youth with anxiety (Conaughton et al., Citation2017; Hepburn et al., Citation2016) and parents of autistic adolescents and adults (Lunsky et al., Citation2021) suggests that virtual delivery is feasible, acceptable, and can help reduce autistic people and parents’ levels of stress and anxiety. None of this research exists within the context of having to manage the demands of the pandemic or changing abruptly from the expectation for in-person treatment to a new online version of an intervention as a result of distancing measures.

Transdiagnostic cognitive behavior therapy (tCBT) is a common approach to addressing multiple kinds of mental health problems in youth and adults by focussing on underlying mechanisms shared across conditions (Ehrenreich-May & Chu, Citation2013; Newby et al., Citation2015). Transdiagnostic interventions use the same treatment principles across mental health disorders, making it possible to address different emotional responses (Barlow et al., Citation2010; Farchione et al., Citation2012), and can be modified for a variety of developmental levels (Ehrenreich-May & Chu, Citation2013). There is evidence for the efficacy of tCBT for children without autism, with moderate effect sizes for both symptoms of anxiety and depression (García-Escalera et al., Citation2016; Kennedy et al., Citation2019), as well as more preliminary work indicating that it can help with anger management and emotion regulation (Grossman & Ehrenreich-May, Citation2020; Loevaas et al., Citation2019). Recent emerging literature indicate that this approach can be useful to address emotion regulation skills in autistic children (Conner et al., Citation2019; Sofronoff et al., Citation2014; Thomson et al., Citation2015). This includes one published randomized control trial to date of 68 autistic children with emotion regulation and mental health challenges, which found significant parent-reported improvements in emotion regulation and psychopathology compared to waitlist controls (Weiss et al., Citation2018). The program, called Secret Agent Society: Operation Regulation (SAS:OR; Beaumont, Citation2013), is an in-person, manualized CBT program, where parent-child dyads participate in individual sessions and learn emotional regulation skills and techniques.

Prior to COVID-19, our research team was evaluating the efficacy of the tCBT program, SAS:OR. In response to COVID-19 physical distancing measures, in-person sessions were postponed, and we adapted the SAS:OR program for online remote delivery. The current study aims to evaluate the feasibility, acceptability, and perceived benefits (i.e., the clinical utility) of online delivered tCBT for autistic children and their parents during the pandemic. We hypothesized that families and therapists would report program participation as satisfactory and that the online program was helpful in teaching emotion regulation and social skills. The current study includes a mixed-methods design of quantitative data collected from parents about the clinical utility of the adapted online version of SAS:OR and qualitative findings from parents and therapists that explore the strengths and challenges of remote emotion regulation program for autistic children.

Method

Participants

A total of 11 parent-child dyads were included in the current study. Children (36% females; Mage = 9.36 years, SDage = 1.02, Range = 8–12) and their primary caregivers (80% females; Mage = 44.63; SDage = 6.57) participated in in-person screening sessions between January to March 2020. Family demographics, parent and child mental health, IQ, emotional regulation and social skills and other direct behavioral assessments were completed. Additional demographic information is presented in . All families met the criteria for participation in the original in-person SAS:OR program. Families were eligible to participate in the intervention if their child: (a) was between 8 and 13 years of age; (b) provided verifiable documentation that confirmed a previously received autism diagnosis from a licensed healthcare professional; (c) met cutoffs on the Social Responsiveness Scale -Second Edition (SRS-2 total T-score cutoff > 59; Constantino & Gruber, Citation2012); (d) performed in at least the average range on intellectual functioning (IQ ≥ 79) on the Vocabulary and Matrix Reasoning subtests of the Weschler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence - Second Edition (WASI-II; Wechsler, Citation2011); and e) had clinically significant emotional or behavioral problems as reported by parents on the Behavioral Assessment System for Children, Third Edition (BASC-3; Reynolds & Kamphaus, Citation2015), or at least one anxiety disorder on the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule – Parent Version (Silverman & Albano, Citation1996). Families were excluded from participating in the in-person SAS:OR program if the child was currently receiving CBT or another treatment focused on emotion regulation, or exhibited aggressive or self-injurious behaviors where safety was a concern. Individuals who did not perform in at least an average range on the WASI-II were excluded because the SAS:OR program was designed for children who could participate independently on tasks that relied on a range of basic and complex reading and rule-following skills.

Table 1. Participant demographics and characteristics (n = 11).

A total of seven therapists (85% females) delivered the SAS:OR program to the families. Therapists included one clinical postdoctoral fellow, three masters-level, and three doctoral-level graduate students in a clinical-developmental program with an average of 3.86 years of experience (SDyears = 6.46, Range = 0–17 years) with autistic children in a clinical setting.

Procedure

Prior to a provincial lockdown (i.e., self-isolation at home) in March 2020, 14 families had completed an initial telephone intake and brief online survey and had come to the university for in-person screening sessions, where they completed primary and secondary outcome measures. Of the 14 families, four started in-person therapy sessions before March 2020 (Msessions = 4.50, Range = 1–6), and the rest were waiting to start therapy. All families had originally expected to receive in-person SAS:OR at the university. Following the March 2020 lockdown, all families were given the option to continue participating in the study using an adapted online version of the program or wait until in-person sessions resumed. Two families discontinued participation because virtual delivery was not preferred, and one dropped out of the study for family reasons. The remaining families (n = 11) who continued with the study received an orientation session to a virutal platform (i.e. Zoom) with their therapists prior to their first virtual therapy session. Families who had already started therapy (n = 4) waited for an average of 21.6 days between their last in-person session and their first virtual session. On average, families received 8.7 virtual SAS:OR sessions (SDsessions = 2.40; Range = 4–10). Parents completed weekly and post-program surveys online. All participants completed their online sessions by November 2020.

Intervention and adaptation

The Secret Agency Society: Operation Regulation (SAS:OR; Beaumont, Citation2013) is a spy-themed manualized tCBT program focused on emotion regulation and social skills. The program includes 10 weekly sessions where a parent and child participate together along with a therapist. Sessions include varying degrees of computer games, in vivo practice, mindfulness-based exercises, and homework review and planning. Prior to March 2020, therapists participated in a 1-day training session where they reviewed the program protocol manual in detail, watched video recordings of sessions, and delivered mock sessions (see Weiss et al., Citation2018 for additional details of the SAS:OR program, therapists training procedures, and treatment integrity). During the suspended period (March 2020 to May 2020), the therapist team received training from the SAS:OR development team in Australia to adapt the program, including the use of physical materials and activities to a virtual platform (i.e., Zoom), and team discussions prepared them for online delivery. Therapists worked through clinical and ethical considerations for remote delivery of an intervention, building rapport and alliance with the child online, and took a problem-based learning approach to practical considerations and implications of delivering a program in a virtual environment.

Specifically, the research and clinical team noted that program delivery should be personalized as much as possible to match the needs of the individual child. For example, therapists were instructed to incorporate child-specific interests in their sessions (e.g., using favorite online games as an incentive, changing Zoom backgrounds to match child interests). Therapists were able to modify the online sessions, including the timing and order of tasks and session duration (e.g., sessions ranged from 30 to 60 minutes), and were permitted to deviate from the manual to accommodate the child’s interests, ability to attend, and behaviors on any given day. Some tasks that were usually completed during in-person sessions and would have required full-body views of the child (including the “Detection of the Expression Game” or “Body Clue Freeze Game”; for details, see Beaumont & Sofronoff, Citation2008) were reassigned as out-of-session activities because the online environment made these tasks difficult to complete (e.g., the camera did not allow for full-body views). Please see Appendix A for a list of specific program adaptations for online delivery.

Measures

Child baseline functioning

Wechsler abbreviated scale of intelligence, second edition (WASI-II; Wechsler, Citation2011)

The WASI-II is a brief intelligence measure. All children completed the two-subtest Full-Scale Intelligence Quotient (FSIQ-2; Vocabulary and Matrix Reasoning), which a composite score is produced that provides an overall measure of cognitive abilities. The WASI-II is a valid and reliable tool that comprehensively evaluates children’s cognitive functioning (McCrimmon & Smith, Citation2013).

Social responsiveness scale, second edition (SRS-2; Constantino & Gruber, Citation2012)

The SRS-2-School Age version is a parent measure used to assess their child’s autism-related social challenges. The SRS-2 includes 65 items that are summed and converted to T-scores to provide an overall indication of symptom severity and five subscale scores: social awareness, social cognition, social communication, social motivation, and repetitive behaviors. The SRS-2 is recognized as a valid measure of autism symptoms and has adequate internal consistency and interrater reliability (Bruni, Citation2014).

Treatment outcome measures

Behavior assessment system for child, third edition – parent rating scales (BASC-3 PRS; Reynolds & Kamphaus, Citation2015)

The BASC-3 PRS is a parent-reported questionnaire used to assess their child’s emotional and behavioral functioning. Comparable composite and subscale scores were produced depending on the child’s age when parents completed either a Child Form (ages 8–11 years) or an Adolescent Form (ages 12–16 years). Parents rated observed behaviors using a 3-point scale (N = Never, S = Sometimes, or O = Often). The current study used Internalizing Problems and Externalizing Problems composite scores.

Emotion regulation and social skills questionnaire (ERSSQ-P; Beaumont & Sofronoff, Citation2008)

The ERSSQ-P is a 27-item parent-report measure used to examine emotional reguationl processes and social skills of autistic youth. Parents were asked to report on the child’s current behaviors using a 5-point Likert scale (0 = “never” to 4 = “always”), with higher scores indicating greater ER and social skills. The ERSSQ-P has been reported to have high internal consistency and concurrent validity in parents of autistic children (Butterworth et al., Citation2014).

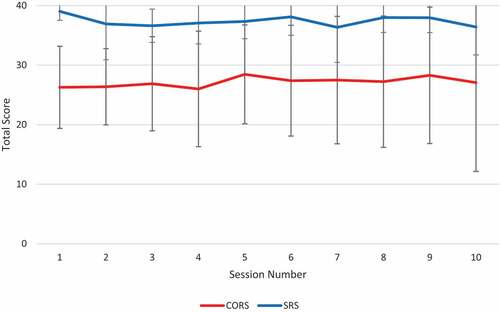

Child outcome ratings scale (CORS; Duncan et al., Citation2006)

The CORS is a 4-item, session-by-session visual analog measure used to assess areas of life functioning known to change during therapy. The CORS is administered at the beginning of each session to each parent to complete about their child, assessing four dimensions: Individual, interpersonal, social, and overall well-being. Parents were asked to place a marker along a 10-point line on the online survey system. Marks closer to the left of the line indicate low levels of functioning, and marks to the right indicate higher levels of functioning. A total score is calculated by adding the four scales (ranging from 0 to 40).

Treatment satisfaction and feasibly measures

Parent session ratings scale (SRS; Miller et al. Citation2003)

The SRS is a 4-item, session-by-session visual analog measure used to assess a parent’s perception of the therapy session and relationship with the therapist. At the end of each session, the SRS is administered to assess four therapeutic relationship dimensions: respect and understanding, goal relevance, relationship fit, and overall therapeutic alliance. Parents were asked to place a marker along a 10-point line on the online survey system. Marks to the left of the line indicating low therapeutic alliance levels, and marks to the right indicate high levels of therapeutic alliance. A total score is calculated by adding the four scales (ranging from 0 to 40).

Program satisfaction questionnaire (Beaumont, Citation2010)

Parents completed the Program Satisfaction Questionnaire at the end of the intervention to assess views on the appropriateness and effectiveness of the program. Open-ended questions asked parents to comment on the child’s emotional reguation skill improvement or acquisition, enjoyment of the program, and satisfaction with the therapist. Parents were also asked to describe their satisfaction with different components of the program on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = “not at all satisfied” to 5 = “very satisfied”). The program components included: venue, therapy date and time, number of sessions and session length, and overall program satisfaction.

Implementation acceptability scale (IAS)

The IAS is a 7-item lab-developed measure administered to assess parent and therapist’s intervention acceptability. Respondents were asked to describe their experience receiving (parents) or providing (therapists) the intervention using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = “strongly disagree” to 5 = “Strongly agree”), higher scores reflecting greater treatment acceptability. Respondents rated questions that refer to aspects of the theoretical framework of acceptability (Sekhon et al., Citation2017), which includes one item each to reflect affective attitude (“I feel positively about this program”), burden (“The amount of effort required to do this program was acceptable”), ethicality (“The program aligned well with my values”), intervention coherence (“I understand this program and how it works”), opportunity costs (“I did not need to give up resources or opportunities in order to participate in this program”), perceived effectiveness (“This program was effective in achieving its goals”), and self-efficacy (“I am confident in my ability to lead this program”).

SAS:OR fidelity checklists

Therapists reported on the total number of activities completed in session per week across the 10 sessions. A percentage score was calculated using the total number of activities completed across sessions divided by the total number of activities to complete across all 10 sessions. In addition, therapists rated items related to the family’s in-session engagement (1 = “Completely Unengaged” to 5 = “Actively Engaged”), ability to complete homework, or “Home Missions,” on a weekly basis (0 = “None” to 2 = “Fully”), and the family’s report of how successful they were in completing the Home Missions (1 = “Unsuccessfully” to 5 = “Successfully”).

Interviews

All interviews were conducted after parents and children completed the SAS:OR program. A semi-structured interview guide was developed using open-ended questions and included follow-up probes to tailor the interview to participants’ responses. The interview guide for parents included questions about their experience during the lockdown (March to November 2020), their initial thoughts about virtual delivery of the SAS:OR program, their experience participating in the virtual program, and recommendations for future delivery (see Appendix B for interview questions). The interview guide for therapists included questions about their thoughts onboarding parents to the SAS:OR program and their experience delivering the program remotely. All interviews were conducted by a clinical-developmental psychology graduate student involved in pre-program screening assessments with the families and had some knowledge of the SAS:OR program. They did not participate in the delivery of the SAS:OR program but was familiar with participants’ presenting problems and intervention components. During the interview, the interviewer shared a verbal summary of participant responses to each of the questions on the interview guide, asked participants to elaborate or correct interpretations, and sought clarification as needed. Each interview ranged from 45 to 60 minutes. Interviews were digitally recorded, and field notes were kept capturing research insights.

Mixed-method design

An explanatory sequential mixed methods design (QUAN/qual) was used (Cresswell & Plano Clark., Citation2007) to explore parental perceptions of the acceptability and feasibility, and overall satisfaction with participating in an adapted online SAS:OR program during the pandemic (). The quantitative phase of data collection was aimed to assess parents’ overall satisfaction with the program, preliminary clinical change in child emotion regulation and mental health challenges, and perceptions of its acceptability in addressing their child’s needs. The qualitative component of data collection was to explain parents’ experience during the pandemic, parents’ and therapists’ perceptions of the transition to the online delivery process, and their thoughts on program suitability for autistic children. In the quantitative phase, parents completed pre- and post-program surveys about children’s overall behaviors, and weekly and post-program evaluations. In the qualitative part of data collection, online and/or telephone interviews were conducted with the parents and program therapists. A thematic content analysis method was used to direct the collection and analysis of the qualitative data. The quantitative data were collected between September 2019 to October 2020, and all qualitative interviews were completed between August and November 2020. The research team met regularly throughout this time frame to discuss and document the steps taken in this research project.

Figure 1. A visual diagram of the mixed-methods study procedure diagram. (Cresswell & Plano Clark., Citation2007).

Data analysis

The study aimed to collect data that tested the acceptability and feasibility of the online adaptation of the SAS:OR program for autistic children and their parents provided during the COVID-19 pandemic. All quantitative analyses, including participant descriptives, program acceptability and satisfaction ratings, therapist fidelity, and paired samples t-tests, were conducted using SPSS version 26. Cohen’s d was calculated to assess for potential within subject effect sizes. The reliable change index was calculated for the ERSSQ-P to assess the number of children that demonstrated clinically meaningful change in emotion regulation and social skills after participating in the SAS:OR program. For the qualitative analysis, all interviews were conducted on a virtual platform (i.e., Zoom) or the telephone, depending on the preference of the parent or therapist. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim by trained research assistants. All identifying information, such as names, schools, city names, were removed to ensure that participants remained anonymous. We followed the six phases of an inductive thematic analysis approach for qualitative coding. This included data familiarity, generating initial codes, searching for themes, reviewing themes, defining and naming themes, and producing a scholarly report (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). The first and second authors reviewed each transcript as the interviews were completed and utilized open coding to capture emerging themes representing the experience of both parents and therapists through the adapted program (Hsieh & Shannon, Citation2005). New themes were added until data saturation was reached, and no new coding categories emerged. Three co-authors and the senior author were included in a peer debriefing process to confirm codes and themes (Lincoln & Guba, Citation1985). If there were any inconsistencies or differing interpretations of the coding schemes, the group would reach a consensus to resolve conflicts.

Results

Quantitative results

Paired samples t-tests showed no significant difference from pre-intervention (M = 69.36, SD = 9.45) to post-intervention (M = 69.72, SD = 10.39) in parent-reported externalizing behaviors (t(10) = −0.85, p = .40, d = .22) and in pre-intervention (M = 65.72, SD = 14.38) and post-intervention (M = 62.18, SD = 11.65) internalizing behaviors (t(10) = 1.85, p = .09, d = 0.44) on the BASC-3 in their child, but did indicate a significant increase in parent-reported child emotion regulation and social skills as measured on the ERSSQ-P, (MPre = 44.09, SD = 9.44; Mpost = 51.90, SD = 11.27; t(10) = −2.89, p = .03, d = 0.84). In our sample, four children showed a reliable or clinically meaningful change (36%), and seven children showed an indeterminate change (58%) on the ERSSQ-P. As shown in , the mean total scores on the CORS and SRS were high and relatively stable across the 10 sessions.

Figure 2. Mean CORS and SRS total scores for each session.

On the post-intervention Program Satisfaction Questionnaire, 82% of parents reported feeling “confident” to “very confident” in their ability to support their child’s future social and emotional development. Parents reported that their child found the program enjoyable (73%), that they were very satisfied with their therapists (100%), they were satisfied with the online “venue” (73%), satisfied or very satisfied with the number and length of sessions (100%), and 82% indicated that they were satisfied or very satisfied with the program overall.

On the post-intervention IAS parents reported feeling positively about the program (90%) and “agreed” or “strongly agreed” that the amount of effort required to do this program was acceptable (90%), aligned with their values (100%), that they understood the program and how it worked (100%), that they did not have to give up resources in order to participate (100%), and that it was effective in achieving their goals (90%). Therapists reported feeling positive about the program (100%) and agreed strongly that the program required an acceptable amount of effort (100%), that the program aligned well their values (100%), that they understood the program and how it worked (100%), that they did not have to give up resources in order to deliver the program (100%), that the program was effective in achieving its goals (81%), and they felt strongly about their ability to lead the program (100%).

On average, therapists reported completing 68.14% (SD = 11.19, Range = 50.58–87.12) of all possible activities across all sessions with the families, and in-session engagement was rated as 4.05 (SD = .78, Range = 2.33–4.83). The remaining activities were often re-assigned as Home Missions. Therapists reported that Home Missions were usually partially completed (M = 1.04, SD = .50, Range = .33–2.0), and they were completed with some success (M = 3.49, SD = .89, Range = 1.80–4.60).

Qualitative results

The qualitative analysis suggested that several factors explained and contributed to the quantitative findings. Parents reported that disruptions due to the pandemic resulted in increases in child emotional and behavioral problems. Parents and therapists noted that families were highly motivated to continue with the program, despite initial parental hesitations with the technology and online format. Parents and therapists noted that rapport and communication were an important component to the family’s satisfaction and confidence in the program. By participating in the program, parents noted that they gained some insight into their child’s behaviors and were able to use common “emotional language” to de-escalate emotionally charged situations. Consistent with parents’ quantitative measures of program satisfaction, parents and therapists reported improvements in the child’s emotion regulation skills after participation in the program. provides a summary of the general themes and subthemes by participant group and relevant quotes.

Table 2. Qualitative themes of parents’ and therapists’ experiences.

Theme 1: behavioral management needs

Changes in child behaviors in response to the pandemic

Parents reported variable experiences during the pandemic. Some parents noted that abrupt changes in their daily routines (e.g., going to school, access to services and interventions) had put additional strain on their lives, and it took some time for their child and family to readjust to the “new normal.” Some parents noted that during this time, their children displayed an increase in emotional and behavioral problems, including extreme frustration, anxiety, and aggression.

At the same time, other parents also noted that social distancing protocols put in place to limit the spread of COVID-19, including transitions to at-home or online learning, had reduced autism-specific stressors, and resulted in fewer behaviors. Therapists confirmed the variation in the lived experiences during the pandemic of the families they were working with, but also reported that despite some positive or neutral experiences, parents still noted increases in behavioral challenges in their children.

Parents were motivated and relieved to return

All parents who chose to continue with the program reported that they were motivated and excited to return to or begin the program online. All parents noted that access to professionals and other services for their child had been postponed due to the pandemic. Many families noted feeling “left behind” by service providers who were unable to adapt their delivery methods to accommodate their child’s needs. Parents reported feeling “relieved” when the research team connected with them a few weeks after postponing the program to let them know of the plans to continue with therapy through an online format. The therapists confirmed these sentiments, as they noted that all parents were very receptive to their initial correspondence to continue with the SAS:OR program, and it was evident through these responses that families were motivated to return. Therapists also noted that as clinicians, they felt a duty to continue providing care considering the potential impact on emotion regulation and mental health of the self-isolation policies put in place during the pandemic:

It was just nice to know that getting the emails from the program, from the coordinators, getting updates where we weren’t just being left out of the loop and forgotten about.

Theme 2: process of onboarding to program

Parents were hesitant about online delivery

Although parents were motivated to return to the program, there were feelings of hesitancy due to the new online format. Some parents noted their children already spent a majority of their day sitting in front of the computer for online school, and they were concerned that adding another virtual activity would be too much. Other parents were hesitant and felt overwhelmed because of their lack of confidence in setting up the technology or equipment required to participate in the sessions.

Most of the therapists already had experience with delivering online therapy because of the pandemic, so they anticipated that parents would feel hesitant with the online format. Therapists felt prepared to support families with the onboarding process for the adapted online program because of their prior online experience and the training sessions provided during the lockdown. Specifically, therapists noted that having discussions about ethical considerations, mitigating risks, and a problem-based approach to managing challenging behaviors were very beneficial to their training.

Parents and therapists appreciated the technology orientation

Parents were less hesitant with managing the technology after their pre-program orientation. Prior to starting weekly online sessions, all therapists engaged their families in a technology and “re-introduction” session via Zoom. Parents were sent detailed instructions on technology and set-up requirements for their Zoom sessions. Parents noted their appreciation of the therapists’ efforts in helping them make the transition to online delivery smoother by giving them step-by-step instructions, as well as being understanding of their needs. Although parents were concerned with potentially having to troubleshoot or deal with technological problems throughout the program, both parents and therapists noted that technological interruptions were minimal or easily managed: “They answered all my questions … it just put my mind at ease.”

Some parents noted that this orientation session gave them the opportunity to update the therapist on their current concerns regarding their child’s emotions and behaviors, and to discuss other relevant issues related to therapy. These sentiments were confirmed by therapists who also felt that the re-introduction sessions allowed them time and space to “get to know” the family outside of a formal therapy setting. Therapists noted that these sessions were important in developing the foundation of a good working relationship with the parent and rapport with the child: “So I think that was really nice … a nice introduction for all of us to really sort of get to meet each other … until, you know, the first session.”

Theme 3: process of program delivery

Child-therapistrelationship

All parents were impressed that their child and therapist were able to establish a “trusting” relationship over an online environment, and even in cases where the therapists had not previously met the child in person. Parents noted that therapists were able to maintain the child’s attention and even after a long day of online schooling.

Therapists noted several approaches for rapport building through a remote-delivery format. In terms of rapport with the families, therapists noted that being proactive in maintaining consistent communication with parents, such as using weekly e-mail reminders and offering debriefing sessions, helped sustain a good working relationship and ensured engagement in the program. In terms of rapport with the child specifically, therapists noted using child-specific interests in therapy, such as using themed virtual backgrounds, and incorporating personalized items (e.g., favorite online games and household pets) into their weekly sessions helped maintain engagement: “Overall, I feel like I was able to build rapport, and at the end, our relationship was comparable to what I think we would have had in person.”

Management of challenging behaviors

Parents felt that therapists were prepared and able to manage and de-escalate challenging behaviors (e.g., aggression, lack of motivation) as they arose throughout the weekly sessions. For example, one parent noted: “If [CHILD] was getting frustrated, [THERAPIST] would pick up on that and try something else … the flexibility was great.” Parents observed that the most challenging behaviors were related to inattention or distractions beyond the computer and within the home environment, situations beyond the therapists’ control. Therapists noted the importance of having the parents be “co-facilitators” during the online sessions. Although most of the interaction during therapy sessions was between the therapist and the child, therapists noted that having an engaged and motivated parent who was available to monitor parts of the session was very helpful, considering therapists were unable to physically work with the child in the same room.

Therapists noted that it was sometimes difficult to manage challenging behaviors and reported several helpful approaches during the online sessions. Specifically, when the challenging behaviors included inattention or distraction, therapists noted using explicit reinforcements (e.g., gift cards or a chance to play a favorite online game), frequent breaks, visual schedules, and verbal validation and praise: “I constantly told him how brave I thought he was for doing this online, and really connected with [him] like that.” Therapists reported that during situations where the child was becoming frustrated and agitated, the best approach in de-escalation was to implement treatment modifications, including changing the order of activities, shortening sessions, and remaining flexible in program delivery. Therapists valued maintaining rapport with the child over remaining “attached to the manual” and “I just think having the flexibility and picking and choosing what works best for [CHILD] was very helpful.”

Theme 4: evaluation of program utility

Parents developed shared “emotional language.”

During online sessions, parents took a secondary role of facilitating the session by setting up the technology and controlling the online programs required for delivery. Through this participation, parents noted that they learned about the different emotion regulation tools and techniques best suited for their child. Parents shared that they now had shared “emotional language or labels” with their child, which was instrumental in helping them communicate and manage emotional outbursts: “Yes, it established a common language in making sure that we both understood the same things together … .it helped us communicate our feelings a lot more.” In some families, the ability to talk about emotions changed the parent-child relationship: “By doing it online, we just bonded in a different way. This still helped us bond as a father and son, we have a better understanding of each other, and I think he respects and appreciates that … ”

Improvements in behaviors

Consistent with the quantitative data, parents and therapists reported observing improvements in emotion regulation and behavioral management skills in children, and linked this to involvement in the program. Parents noted seeing their child use the skills and program gadgets included in the SAS:OR program kits during at-home discussions about emotional outbursts and even during online schooling (e.g., discussion with teachers about emotions). For example, one parent noted: “Things have been improving extremely well with [CHILD] since starting this program. The difference in his ability to recognize feelings and understand how those feelings not only are affecting him, but others, is just day and night.”

Benefits and challenges of online delivery

Parents noted that the online delivery was sometimes challenging considering the amount of time children spent online during the beginning of the pandemic. Parents noted that sometimes environmental distractions (e.g., lack of privacy, busy household) made it difficult for the child to concentrate on the online session. In these times, the fun, flexible, and game-based nature of the program delivery made redirection of attention relatively easy for the therapists to reengage the child in the tasks at hand. Parents noted that it was difficult to complete all the Home Missions in between sessions. Some parents noted that they missed traveling to the university campus to participate in person because it was a great time to bond with their child. Other parents noted that less traveling each week made it easier for them to participate in the program: “So … the travel is one … I mean it’s also less expensive if you’re not going to [the city].”

Therapists had some concerns about maintaining privacy during sessions because most of the children lived in busy multi-person households. They reported that the children they worked with did learn some skills through participation (e.g., relaxation techniques). However, they questioned whether the flexibility in delivery (e.g., personalized approach, and not adhering to the manual and skipping components of the program) interfered with the efficacy of the program to improve emotion regulation for some children. For example, therapists reported that shortening sessions meant that tasks were re-assigned as Home Missions to be completed offline, and there were questions about whether completing these tasks on their own was just as effective as completing them with the guidance of a therapist. Therapists did note that it was probably more beneficial to deliver some components of the program online rather than having no therapy at all.

My biggest worry was if I cut out activities, am I not providing them with the full opportunity to engage in the program? And I quickly realized that this is still a pretty broad program that … it hits multiple presenting problems.

Discussion

This study is among the first to explore the experience of parents who participated in a 10-week tCBT program adapted to an online format for autistic children within the context of a global pandemic. The ORBIT model for behavioral treatment development (Czajkowski et al., Citation2015) highlights the importance of conducting acceptability and feasibility studies to determine the clinical utility (e.g., does the program produce clinically meaningful improvements?) of a treatment program before using more rigorous efficacy and effectiveness research. Given the ongoing uncertainty and lockdowns that have limited in-person access to services and programs for autistic children who struggle with mental health problems (Asbury et al., Citation2020; Colizzi et al., Citation2020; Imran et al., Citation2020), this study is an important first step in establishing the clinical utility of online mental health treatments for autistic children and their parents.

In the current study, parents reported a significant improvement in emotional regulation in their children between pre- and post-intervention; even though pre-intervention measures of skills were collected before March 2020 (i.e., pre-lockdown), and post-intervention measurements were captured while families were still within the pandemic. Only a small proportion of our sample, however, demonstrated clinically meaningful change in emotion regulation skills. Nevertheless, the overall improvement suggests that there was a benefit to participating in the online program for autistic children. Both parents and therapists reported that children in the program learned new emotion regulation skills through participation in activities during the online sessions. At the same time, parents did not report statistically significant changes in internalizing or externalizing symptoms during this time, with only small to moderate within subject effect sizes noted. Given the lack of power associated with the sample, and the fact that qualitatively, parents reported increased behavioral challenges observed during the lockdown period, it is difficult to ascertain why there was no statistical change, and whether there is an issue of dose, of treatment modification, or of stressors. It is commonly thought that treatment change is best explained by a combination of treatment-specific, common, and extra-therapeutic factors (Kadzin & Nock, Citation2003), and it is hard to know how each of these factors contributed to the current pre-post findings. The session-by-session outcome rating scale suggests that children’s functioning remained relatively stable as a group, though the standard deviations also point to tremendous variability, which again speaks to the importance of understanding family experiences from a qualitative perspective.

The current study demonstrated that participation in the adapted online program was acceptable and feasible for the autistic children and their parents who chose to continue the program in a new format. Most parents chose to participate in this online version rather than wait for in-person treatment to resume, and all these families completed the program. It is important to note that some parents chose not to continue with the virtual format, and their perspectives have not been reflected here. Parents reported high satisfaction with the timing of the program, number of sessions, the relationship with their therapists, and even with the remote and online format of the adapted program. These results are consistent with parents’ and therapists’ qualitative reports of “high motivation” to participate in the program, the ability for the child and therapist to develop and maintain rapport through an online platform, and general contentment associated with participation. Indications of acceptability and feasibility reveal that parents and therapists both felt that the perceived benefits of the program outweighed the demands of the program, suggesting that they found the program suitable and appropriate, with some clinical benefits for the child.

In the rapid shift toward online mental health care delivery, it is important to consider clinical best practices when supporting parents and their autistic children. The current study highlights three practical considerations: 1) the use of an orientation session, 2) considerations of video conferencing fatigue, and 3) intervention modification. In the current study, both parents and therapists highlighted the importance of a “pre-therapy” orientation session that provided parents with instructions on how best to organize and manage the technology required for participation in the program. Parents were provided with written instructions, and therapists were able to work with them to ease their concerns about participating online. The orientation session allowed for troubleshooting around the technology, answer family questions and socializing them to the structure of the online session. Orientation sessions have long been an aspect of CBT provision to children and taking a family-centered approach to managing the logistics of the current shift speaks to the importance of preparing children and their parents for treatment (Driscoll et al., Citation2020). Considerations at the time of orientation should also be made for a family’s technological limitations or added demands associated with participation. Although we were able to ensure that families had access to technology (e.g., computer or tablet, and high-speed internet) during orientation, not all families who need treatment will have the technological resources required for participation and having alternative options available will be important (e.g., tablet loans). For some children, parents will have to play a more active role in managing the technology during sessions (i.e., parent as the co-facilitator).Orientation sessions should consider factors related to a parent’s ability to participate (i.e., Will this lead to parent burn out? Is participating adding to parental burden?).

Our qualitative research suggests the importance of considering video conferencing fatigue for children and parents. Past studies have focused on growing parental and clinician concerns surrounding increases in screen time for autistic children (Garcia et al., Citation2020; Dong et al., Citation2021), but especially during the pandemic (Chen et al., Citation2020), with increased online time being related to decreases in physical activity (Garcia et al., Citation2020), sleep abnormalities (Türkoğlu et al., Citation2020), and mental health concerns (Chen et al., Citation2020; Imran et al., Citation2020). This problem may be compounded as children spend more time online each day due to changes to in-person schooling due to lockdowns. Given the number of interventions and services that are moving toward telehealth delivery during the pandemic, the benefits of participating in an online therapy should outweigh the cost of adding more screen time for autistic children. Parents in our study initially indicated concerns with adding another “online activity” for their child; both parents and therapists noted that children generally benefited from participating in the online sessions.

Our results speak to the importance of modifying the delivery of the manualized program for individualized care. The online delivery of a manualized intervention designed for in-person treatment presents unique challenges to therapists, as it can make their ability to adhere to the prescribed tasks and activities more difficult during each session. Therapists reported that this gave them pause about the program’s efficacy, but maintaining rapport and engagement with the child took precedence over meeting all session goals (e.g., completing all session tasks), especially if this meant preventing challenging behaviors from escalating within the child’s home. Therapists reported completing on average 68% of the tasks across all sessions, and that tasks that were assigned as homework were completed partially and with some success. This suggests that families were able to engage with and learn from some of the material independently.

Therapists reported adapting their program delivery by making the sessions shorter, rearranging the order of tasks or reassigning session tasks for homework, adding child-led topics to the session agenda, and playing more online games with the child rather than completing in-session missions. Specific modifications for online delivery included allowing the child to go off-camera or use a mask if they were shy, allowing them to move around the room while still engaged in conversation online, sharing an interactive screen via the online platform to complete a task together, and utilizing more “chill-out” gadgets during sessions. Prior scholarship has emphasized that manualized CBT for children should be provided in a flexible manner, ensuring that therapeutic alliance is maintained and that the clients’ unique needs are taken into account (Beidas et al., Citation2010; Pickard et al., Citation2021; Sung et al., Citation2011). Although this may not be ideal for maintaining program fidelity, personalized modifications to program delivery made the online adaptation of the program feasible and accessible for children. Despite the modifications to the program, parents reported seeing changes in child emotion regulation skills, and both parent and therapist interviews revealed that children learned new skills by participating. Future research is needed to understand how online programs maintain “active ingredients” in treatment to maintain effectiveness.

Frameworks for evaluating the use of digital supports can be a useful next step in planning more rigorous evaluations of newly adapted online mental health care. Recent consensus guidelines on the kinds of evidence deemed useful include tests of reliability, engagement, and technology effectiveness (Zervogianni et al., Citation2020, Citationin press). Further development of engaging and targeted online mental health programs for autistic children could include the use of consensus-building techniques such as Delphi study methodology (Linstone & Turoff, Citation1975), to bring together the expertise of all relevant stakeholders, including parents, children, as well as autism-related professionals and researchers (i.e., clinicians, technology experts, interventionists, etc.). Delphi techniques have been used before to identify how CBT could be adapted for autistic clients (Spain & Happé, Citation2020), on the development of virtual reality-based social stories (Ghanounin et al., Citation2019), and defining best practices in care (Ager et al., Citation2010).

Limitations and future considerations

There are important limitations to our findings. First, the lack of controls (e.g., waitlist comparison group) in the current study undermines our ability to determine if changes in emotional regulation and social skills were due to participation in the program or increased amount of time at home with parents, or other contributing factors. The study had a small sample size, and we used a convenience sample of participants (i.e., those already participating in a previous study and who were willing to continue the program virtually) and who had the resources to access technology and high-speed internet, which limits our ability to generalize findings to families who may have faced barriers to participation. Further, our sample only included children with at least an average cognitive ability, which limits our ability to speak to the feasibility and acceptability of adapted online programs for children with intellectual impairments and more complex behavioral needs. We also did not report follow-up data for the current sample, and more long-term evaluations will be needed to understand whether emotion regulation skills are maintained after participation in the program. Additionally, child emotion regulation and mental health challenges were assessed solely through parent-reported measures, and only some children demonstrated a clinically meaningful change in emotional regulation skills post-intervention. Future evaluations of the program should consider using a multi-method approach to assess outcomes (i.e., child-report measures, online observations of child behaviors). Finally, it will be important for further studies to include randomized controlled trials to determine the treatment efficacy of the adapted online SAS:OR program compared to other mental health programs. It would be crucial for these studies to have a concurrent comparison to in-person programs.

Despite these limitations, the current study contributes to our understanding of engagement and the impact of an online tCBT for autistic children and their parents. Although there are clear challenges to online delivery, it may be that online programs that target mental health in autistic children are beneficial, and the current research indicates that they can be delivered in a way that is acceptable to both parents and therapists. Given the prevalence of mental health challenges in autistic children and the unpredictability of stable access to mental health services due to the pandemic, it is critical that we continue to find innovative ways of providing supports to this population.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (36.8 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors thank the families who participated in this research study.

Disclosure statement

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from York University in June, 2020. Parents provided informed consent prior to study participation.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 A note about the use of autistic children when communicating about autism in this article. We acknowledge that there continue to be differences in how to refer to autism: in keeping with recent scholarship on the use of identify first language (Bottema-Beutel et al., Citation2021; Kenny et al., Citation2016), our usage of identity-first language is meant to recognize, affirm and validate the ownership of identity for autistic people.

References

- Ager, A., Stark, L., Akesson, B., & Boothby, N. (2010). Defining best practice in care and protection of children in crisis‐affected settings: A Delphi study. Child Development, 81(4), 1271–1286. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01467.x

- Asbury, K., Fox, L., Deniz, E., Code, A., & Toseeb, U. (2020). How is COVID-19 affecting the mental health of children with special educational needs and disabilities and their families? Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 51, 1772–1780. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04577-2

- Barlow, D. H., Ellard, K. K., & Fairholme, C. P. (2010). Unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders: Workbook. Oxford University Press.

- Beaumont, R. (2010). The SAS:OR facilitator manual. The Social Skills Training Institute.

- Beaumont, R. (2013). Secret Agent Society – Operation Regulation (SAS-OR) Manual. Social Skills Training Pty Ltd.

- Beaumont, R., & Sofronoff, K. (2008). A multi-component social skills intervention for children with asperger syndrome: The junior detective training program. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49(7), 743–753. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01920.x

- Beaumont, R., Walker, H., Weiss, J. A., & Sofronoff, K. (2021). Randomized controlled trial of a video gaming-based social skills program for children on the autism spectrum. Journal of Developmental Disorders, 1–14. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04801-z

- Beidas, R. S., Benjamin, C. L., Puleo, C. M., Edmunds, J. M., & Kendall, P. C. (2010). Flexible applications of the coping cat program for anxious youth. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 17(2), 142–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2009.11.002

- Bottema-Beutel, K., Kapp, S. K., Lester, J. N., Sasson, N. J., & Hand, B. N. (2021). Avoiding ableist language: Suggestions for autism researchers. Autism in Adulthood, 3(1), 18–29. https://doi.org/10.1089/aut.2020.0014

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Bruni, T. P. (2014). Test review: Social responsiveness scale – Second edition (SRS-2). Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 32(4), 365–369. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734282913517525

- Butterworth, T. W., Hodge, M. A. R., Sofronoff, K., Beaumount, R., Gray, K. M., Roberts, J., Horstead, S. K., Clarke, K. S., Howlin, P., Taffe, J. R., & Einfeld, S. L. (2014). Validation of the emotion regulation and social skills questionnaire for young people with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(7), 1535–1545. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-013-2014-5

- Chen, I. H., Chen, C. Y., Pakpour, A. H., Griffiths, M. D., & Lin, C. Y. (2020). Internet-related behaviors and psychological distress among schoolchildren during COVID-19 school suspension. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 59(10), 1099. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2020.06.007

- Colizzi, M., Sironi, E., Antonini, F., Ciceri, M. L., Bovo, C., & Zoccante, L. (2020). Psychosocial and behavioral impact of COVID-19 in autism spectrum disorder: An online parent survey. Brain Sciences, 10(6), 341. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci10060341

- Conaughton, R. J., Donovan, C. L., & March, S. (2017). Efficacy of an internet-based CBT program for children with comorbid high functioning autism spectrum disorder and anxiety: A randomised controlled trial. Journal of Affective Disorders, 218 (August), 260–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.04.032

- Conner, C. M., White, S. W., Beck, K. B., Golt, J., Smith, I. C., & Mazefsky, C. A. (2019). Improving emotion regulation ability in autism: The emotional awareness and skills enhancement (EASE) program. Autism, 23(5), 1273–1287. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361318810709

- Constantino, J. N., & Gruber, C. P. (2012). Social responsiveness scale—Second edition (SRS-2). Western Psychological Services.

- Cresswell, J., & Plano Clark., V. (2007). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Sage.

- Czajkowski, S. M., Powell, L. H., Adler, N., Naar-King, S., Reynolds, K. D., Hunter, C. M., Laraia, B., Olster, D. H., Perna, F. M., Peterson, J. C., Epel, E., Boyington, J. E., & Charlson, M. E. (2015). From ideas to efficacy: The ORBIT model for developing behavioral treatments for chronic diseases. Health Psychology, 34(10), 971–982. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000161

- Dong, H.-Y., Wang, B., Li, H.-H., Yue, X.-J., & Jia, F.-Y. (2021). Correlation between screentime and autistic symptoms as well as developmental quotients in children with autism spectrum disorder. Frontiers Psychiatry,12(619994), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6381-x

- Driscoll, K., Schonberg, M., Stark, M. F., Carter, A. S., & Hirshfeld-Becker, D. (2020). Family-centered cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety in very young children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(11), 3905–3920. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04446-y

- Duncan, B. L., Sparks, J. A., Miller, S. D., & Bohanske, R. T., & Claud, D. A. (2006). Giving youth a voice: A preliminary study of the reliability and validity of a brief outcome measure for children, adolescents, and caretakers. Journal of Brief Therapy, 5(2), 71–88. https://www.scottdmiller.com/wp-content/uploads/CORS%20JBT%20(2).pdf

- Ehrenreich-May, J., & Chu, B. C. (2013). Transdiagnostic treatments for children and adolescents: Principles and practice. Guilford Publications.

- Eisenberg, N., Cumberland, A., Spinrad, T. L., Fabes, R. A., Shepard, S. A., Reiser, M., Murphy, B. C., Losoya, S. H., & Guthrie, I. K. (2001). The relations of regulation and emotionality to children’s externalizing and internalizing problem behavior. Child Development, 72(4), 1112–1134. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00337

- Farchione, T. J., Fairholme, C. P., Ellard, K. K., Boisseau, C. L., Thompson-Hollands, J., Carl, J. R., Gallagher, M. W., & Barlow, D. H. (2012). Unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders: A randomized controlled trial. Behavior Therapy, 43(3), 666–678. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2012.01.001

- Fegert, J. M., Vitiello, B., Plener, P. L., & Clemens, V. (2020). Challenges and burden of the coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic for child and adolescent mental health: A narrative review to highlight clinical and research needs in the acute phase and the long return to normality. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 14(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-020-00329-3

- Furgeson, J., Craig, E. A., & Dounavi, K. (2019). Telehealth as a model for providing behaviour analystic interventions to individuals with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(2), 582–616. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3724-5

- Garcia, J. M., Lawrence, S., Brazendale, K., Leahy, N., & Fukuda, D. (2020). Brief report: The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on health behaviors in adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Disability and Health Journal, 14(2), 101021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2020.101021

- García-Escalera, J., Chorot, P., Valiente, R. M., Reales, J. M., & Sandín, B. (2016). Efficacy of transdiagnostic cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety and depression in adults, children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Revista de Psicopatología y Psicología Clínica, 21(3), 147–175. https://doi.org/10.5944/rppc.vol.21.num.3.2016.17811

- Ghanounin, P., Jarus, T., Zwicker, J. G., Lucyshyn, M. K., & Ledigham, A. (2019). Social stories for children with autism spectrum: Validating the content of a virtual reality program. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorder, 49(2), 660–668. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3737-0

- Grossman, R. A., & Ehrenreich-May, J. (2020). Using the unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders with youth exhibiting anger and irritability. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 27(2), 184–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2019.05.004

- Hepburn, S. L., Blakeley-Smith, A., Wolff, B., & Reaven, J. A. (2016). Telehealth delivery of cognitive-behavioral intervention to youth with autism spectrum disorder and anxiety: A pilot study. Autism, 20(2), 207–218. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361315575164

- Hsieh, H. F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

- Imran, N., Zeshan, M., & Pervaiz, Z. (2020). Mental health considerations for children & adolescents in COVID-19 pandemic. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences, 36(COVID19–S4), S67–S72. https://doi.org/10.12669/pjms.36.COVID19-S4.2759

- Kadzin, A. E., & Nock, M. K. (2003). Delineating mechanisms of change in child and adolescent therapy: Methodological issues and research recommendations. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 44(8), 1116–1129. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00195

- Kennedy, S. M., Bilek, E. L., & Ehrenreich-May, J. (2019). A randomized controlled pilot trial of the unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders in children. Behavior Modification, 43(3), 330–360. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445517753940

- Kenny, L., Hattersley, C., Molins, B., Buckley, C., Povey, C., & Pellicano, E. (2016). Which terms should be used to describe autism? Perspectives from the UK autism community. Autism, 20(4), 442–462. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361315588200

- Lai, M. C., Kassee, C., Besney, R., Bonato, S., Hull, L., Mandy, W., Szatmari, P., & Ameis, S. H. (2019). Prevalence of co-occurring mental health diagnoses in the autism population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry, 6(10), 819–829. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30289-5

- Lee, V., Albaum, C., Tablon Modica, P., Ahmad, F., Gorter, J. W., Khanlou, N., McMorris, C., Lai, J., Harrison, C., Hedley, T., Johnston, P., Putterman, C., Spoelstra, M., & Weiss, J. A. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 on the mental health and wellbeing of caregivers and families of autistic people: A rapid synthesis review. Report prepared for the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/52048.html

- Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Sage.

- Linstone, H. A., & Turoff, M. (Eds.). (1975). The delphi method. Addison-Wesley.

- Liu, J. J., Bao, Y., Huang, X., Shi, J., & Lu, L. (2020). Mental health considerations for children quarantined because of COVID-19. The Lancet Child and Adolescent Health, 4(5), 347–349. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30096-1

- Loevaas, M. E. S., Sund, A. M., Lydersen, S., Neumer, S. P., Martinsen, K., Holen, S., Patras, J., Adolfsen, F., & Reinfjell, T. (2019). Does the transdiagnostic EMOTION intervention improve emotion regulation skills in children? Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28(3), 805–813. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-018-01324-1

- Lunsky, Y., Albaum, C., Baskin, A., Hastings, R. P., Hutton, S., Steel, L., Wang, W., & Weiss, J. (2021). Group virtual mindfulness-based intervention for parents of autistic adolescents and adults. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 51(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04835-3

- Mazefsky, C. A., Herrington, J., Siegel, M., Scarpa, A., Maddox, B. B., Scahill, L., & White, S. W. (2013). The role of emotion regulation in autism spectrum disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 52(7), 679–688. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2013.05.006

- McCrimmon, A. W., & Smith, A. D. (2013). Review of weschler abbreviated scale of intelligence, second edition (WASI-II). Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 31(3), 337–341. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734282912467756

- Miller, S. D., Duncan, B. L., Brown, J., Sparks, J., & Claud, D. (2003). The outcome rating scale: A preliminary study of the reliability, validity and feasibility of a brief visual analog measure. Journal of Brief Therapy, 2, 91–100. https://www.scottdmiller.com/wp-content/uploads/documents/OutcomeRatingScale-JBTv2n2.pdf

- Moltrecht, B., Deighton, J., Patalay, P., & Edbrooke-Childs, J. (2020). Effectiveness of current psychological interventions to improve emotion regulation in youth: A meta-analysis. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 30(6), 829–848. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-020-01498-4

- Mutluer, T., Coenyas, C., & Genc, H. A. (2020). Behavioral implications of the covid-19 process for autism spectrum disorder and individuals’ comprehension of and reaction to the pandemic conditions. Frontier Psychiatry, 11, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.561882

- Newby, J. M., McKinnon, A., Kuyken, W., Gilbody, S., & Dalgleish, T. (2015). Systematic review and meta-analysis of transdiagnostic psychological treatments for anxiety and depressive disorders in adulthood. Clinical Psychology Review, 40(August), 91–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2015.06.002

- Peterson, K. M., Piazza, C. C., Luczynski, K. C., & Fisher, W. W. (2017). Virtual-care delivery of applied-behavior-analysis services to children with autism spectrum disorder and related conditions. Behavior Analysis: Research and Practice, 17(4), 286–297. https://doi.org/10.1037/bar0000030

- Pickard, K., Mellman, H., Frost, K., Reaven, J., & Ingersoll, B. (2021). Balancing fidelity and flexibility: Usual care for young children with an increased likelihood of having autism spectrum disorder within an early intervention system. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 1–13. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-021-04882-4

- Reynolds, C. R., & Kamphaus, R. W. (2015). Behavior assessment system for children (3rd ed.). NCS Pearson, Inc.

- Sekhon, M., Cartwright, M., & Francis, J. J. (2017). Acceptability of healthcare intervention: An overview of reviews and development of a theoretical framework. BMC Health Services Research, 17(88), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2031-8

- Silverman, W. K., & Albano, A. M. (1996). The anxiety disorders interview scheduled for children for DSM-IV: Clinician manual (Parent version). Oxford University Press.

- Simonoff, E., Pickles, A., Charman, T., Chandler, S., Loucas, T., & Baird, G. (2008). Psychiatric disorders in children with autism spectrum disorders: Prevalence, comorbidity, and associated factors in a population-derived sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 47(8), 921–929. https://doi.org/10.1097/CHI.0b013e318179964f

- Sloan, E., Hall, K., Moulding, R., Bryce, S., Mildred, H., & Staiger, P. K. (2017). Emotion regulation as a transdiagnostic treatment construct across anxiety, depression, substance, eating and borderline personality disorders: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 57(November), 141–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2017.09.002

- Sofronoff, K., Beaumont, R., & Weiss, J. A. (2014). Treating transdiagnostic processes in ASD: Going beyond anxiety. T. E. Davis, S. W. White, & T. H. Ollendick Eds., Handbook of autism and anxiety; handbook of autism and anxiety. (pp. 171–183, Chapter xix, 264 Pages). Springer International Publishing AG.

- Spain, D., & Happé, F. (2020). How to optimise cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) for people with autism spectrum disorders (ASD): A Delphi study. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behaviour Therapy, 38(2), 184–208. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10942-019-00335-1

- Sung, M., Ooi, Y. P., Goh, T. J., Pathy, P., Fung, D. S., Ang, R. P., Chua, A., & Lam, C. M. (2011). Effects of cognitive-behavioral therapy on anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorders: A randomized controlled trial. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 42(6), 634–649. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-011-0238-1

- Thomson, K., Burnham Riosa, P., & Weiss, J. A. (2015). Brief report of preliminary outcomes of an emotion regulation intervention for children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(11), 3487–3495. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-015-2446-1

- Torales, J., O’Higgins, M., Castaldelli-Maia, J. M., & Ventriglio, A. (2020). The outbreak of COVID-19 coronavirus and its impact on global mental health. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 66(4), 317–320. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764020915212

- Totsika, V., Hastings, R. P., Emerson, E., Lancaster, G. A., & Berridge, D. M. (2011). A population-based investigation of behavioural and emotional problems and maternal mental health: associations with autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disability. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 52(1), 91–99. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02295.x

- Türkoğlu, S., Uçar, H. N., Çetin, F. H., Güler, H. A., & Tezcan, M. E. (2020). The relationship between chronotype, sleep, and autism symptom severity in children with ASD in COVID-19 home confinement period. Chronobiology International, 37(8), 1207–1213. https://doi.org/10.1080/07420528.2020.1792485

- Vaillancourt, T., Haltigan, J. D., Smith, I., Zwaigenbaum, L., Szatmari, P., Fombonne, E., Waddell, C., Duku, E., Mirenda, P., Georgiades, S., & Bennett, T. (2017). Joint trajectories of internalizing and externalizing problems in preschool children with autism spectrum disorder. Development and Psychopathology, 29(1), 203–214. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579416000043

- Wechsler, D. (2011). Wechsler abbreviated scale of intelligence, second edition (WASI-II). NCS Pearson.

- Weiss, J. A. (2014). Transdiagnostic case conceptualization of emotional problems in youth with ASD: An emotion regulation approach. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 21(4), 331–350. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12915

- Weiss, J. A., Thomson, K., Burnham Riosa, P., Albaum, C., Chan, V., Maughan, A., Tablon, P., & Black, K. (2018). A randomized waitlist-controlled trial of cognitive behavior therapy to improve emotion regulation in children with autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 59(11), 1180–1191. https://doi.org/10.1111/cpsp/12084

- Zervogianni, V., Fletcher-Watson, S., Herrera, G., Goodwin, M., Triquell, E., Pérez-Fuster, P., Brosnan, M., & Grynszpan, O. (in press). Assessing evidence-based practice and user-centered design for technology-based supports for autistic users. PLOS ONE.

- Zervogianni, V, Fletcher-Watson, S., Herrera, G., Goodwin, M., Pérez-Fuster, P., Brosnan, M., & Grynszpan, O. (2020). A framework of evidence-based 1455 practice for digital support, co-developed with and for the autism community. Autism, 24(6), 1411–1422. https://doi.org/10.1177/136236131989833110.1177/1362361319898331