ABSTRACT

Urban margins in the postcolonial context represent a specific form of urban territory in which the state maintains heterogeneous relationships with the political society. I define these relationships as spatial adhocism, quasi-permanent arrangements where the legality of space and rights are ambivalent. This paper elucidates this framework by drawing on the ethnographic study of eviction in squatter settlements of Salt Lake, Kolkata. The ethnography shows that the political society and the state enter a condition of ongoing temporary occupation to practice various forms of conflict politics with each other. These practices are ad hoc because they manifest spatially in semi-permanent ways. Furthermore, the paper highlights two purposes that spatial adhocism serves. On the one hand, it enables the state to accumulate capital subtly and promotes a selective allowance of rights for the political society. On the other hand, it allows political society to counter certain state practices by resisting eviction. The paper also argues how urban territories can be theorised as heterogeneous relationships between the postcolonial state and political society. In doing so, this paper offers an alternative framework to understand territory through the concept of spatial adhocism, thus establishing how urban territory is an incomplete category.

Introduction

On a cold December morning in 2017, I was sitting with the local councillor in her office discussing the recent eviction in Salt Lake. A middle-aged man called AsimFootnote1 entered the office and sat next to the councillor, listened to our discussions, and commented on why the hawkers of Kolkata do not deserve any form of rehabilitation. The final part of our discussion was related to the ‘(il)legal’ Bangladeshi migrants who were living in the squatter settlements of Salt Lake. Our conversation was about to end, and while I was preparing to leave the office, Asim suddenly interjected to tell me that the person I was speaking and having tea with last Sunday was from Bangladesh. The Sunday tea was a reference to my interactions with squatter dwellers in Salt Lake that was part of my fieldwork. Prior to this moment, I was under the impression that I was conducting my research with discretion. This interjection made it clear to me that my research activities have been under surveillance by the state and its apparatus (here Asim) without my knowledge. This incident highlights several practices that illustrate how the postcolonial state uses urban territories for surveillance and how these territories act as oeuvres of networked relations of power where claims of legality and illegality are contested (Painter Citation2010). Drawing on the eviction and associated counter-politics by squatter dwellers in Salt Lake, Kolkata, this paper proposes a multi-layered and relational understanding of territories that establishes them as semi-permanent or ad hoc spatial arrangements. Thus, it constructs territories as heterogeneous political relations and unsettles the Eurocentric notion of territory.

For a decolonial understanding of territories, this paper argues that territories are continuously produced and reproduced through struggles and conflict politics. To this end, this paper develops an empirically driven framework, I call spatial adhocism, which demonstrates heterogeneous relationships between the state and political society reconstructing territory as a quasi-permanent or ad hoc site where multiple political relations are manifested. Spatial adhocism as a framework for a decolonial understanding of territories proposes two formulations. Firstly, it empirically demonstrates that heterogeneous relationships between the postcolonial state and political society are manifested through quasi-permanent spatial arrangements in urban territories. Secondly, it proposes for a decolonial understanding of territories; it is essential to conceptualise them as an incomplete category. Urban territories are incomplete through their temporal precariousness; hybrid through their various assemblages of power, resources, and contingent spatial practices; and are relational through their dynamicity and contextuality.

The paper is structured in the following way. First, it discusses the current scholarship on territory and demonstrates how urban territories can be understood as zones of permanent temporariness. In this second section, I also introduce the concept of conflict politics by configuring it as the complexity of heterogeneous relationships between the postcolonial state and political society. The third section contextualises the making and unmaking of territorial claims in Salt Lake, Kolkata, following an anti-eviction movement. By doing so, it analyses the nature of conflict politics that is associated with the eviction of squatter dwellers of Salt Lake. In its fourth section, the paper introduces the framework of spatial adhocism. Using empirics, it shows how such a framework is relevant in the context of postcolonial urban to understand the nuances of urban territories. Lastly, the paper highlights how the framework of spatial adhocism provides an alternative framework for a decolonial understanding of urban territories.

Towards a decolonial understanding of the territory

By mobilising a framework for spatial adhocism, this paper defines urban territories as an incomplete category of spatial arrangements and empirically shows how these territories demonstrate heterogeneous relations between the state and political society. This heterogeneity comes from a selective allowance of rights to the people at the margins of urban territory by the postcolonial state (Chatterjee Citation2004). This selective allowance results from limited resources by the state, and the state mobilises a de-facto populist politics through political society (Vinay and Reddy Citation2011). However, this paper argues, with the help of the spatial adhocism framework, that political society is not a mere recipient of the state’s calculative de facto politics but an active agent in shaping those politics through ‘strategic essentialism’ (Spivak Citation2012).

Various studies have already identified that territories need to be understood as social relations, which opens up possibilities for defining territories beyond bounded spatial units and highlights how differential power relations are embedded within them (Elden Citation2010; Painter Citation2010). It is also argued to conceptualise territories as overlapping and interconnected socio-spatial relations (Cochrane and Ward Citation2012). These studies also propose an understanding of territories through dynamic social relations and contestation among various actors (Mason-Deese, Habermehl, and Clare Citation2020; Stienen Citation2020). Adopting such an approach unsettles the myopic idea of territories as a place-making exercise and goes beyond the Eurocentric binary framework of analysis (López and Claudia Citation2020; Gieseking Citation2016).

However, this theorisation is often centred around the state’s involvement in defining territories and lacks acknowledging the differences and heterogeneity of these relations from ‘elsewhere’ for the production of territories (Schwarz and Streule Citation2016; Halvorsen Citation2019). For Simone (Citation2020), understanding urban territories requires dislocating it from it being ‘settled’ anywhere rather than an open-ended and generative practice (Simone Citation2020). For him, ‘settling’ somewhere is always problematic as it signifies the extension of colonial relations and practices. Studies using a settler-colonial framework define territories as spaces for occupation and sovereign control by the state (Yacobi and Tzfadia Citation2019; Osuri Citation2017). In such a context, territories are frontiers that are amorphous and not a completely formed category (Hughes Citation2020). Hughes (Citation2020) introduces the idea of ‘unbounded territoriality’, which is operationalised through a process of expansion and subsequent occupation of the frontier. Ince (Citation2012) proposes territories as autonomous units often produced through everyday practices and embedded in the revolutionary imaginations of autonomy. Conceptualising territories as autonomous units helps us to dislocate them from a state-centred understanding and unsettles Eurocentric conceptualisations of them by foregrounding resistance from below (Halvorsen, Mançano Fernandes, and Valeria Torres Citation2019; Ince Citation2012). In this way, territories become multiple political projects with varied political relationships with the state, and a decolonial scholarship may help engage with such struggles from within. To understand this, the next section discusses how urban territories in the postcolonial context become an oeuvre for multiple political relationships.

Multiple political relationships in territories

Drawing from the above discussion on territories, these multiplicities of relations and the amorphous nature are more visible when we situate territories in the postcolonial urban context. In the postcolonial context, the urban territories are an extension of colonial power relations and act as a discursive field for subaltern political actions (Roy Citation2011; Sheppard et al, Citation2013) These subaltern political actions are operationalised by what Chatterjee (Citation2011) identifies as political society. ‘Political society’ in Chatterjee’s (Citation2011) conceptualisation operates outside the legitimacy of law and practices discursive politics with the state. He sees political society as distinctively different from ‘civil society’, which is governed by the rule of law and spaces of corporate capital (Chatterjee Citation2011). Building on Chatterjee’s (Citation2004, Citation2011) theorisation, this paper situates it in the urban territories of Kolkata and explores how claims by political society are spatially manifested in a postcolonial context. It sees the postcolonial state as an extension of social relations of control (Jessop Citation2012), where it maintains an elusive boundary with its citizen subjects (Chatterjee Citation2004; Das Citation2004). This ambiguity helps the postcolonial state to maintain a Janus-faced identity, where dispossession and rehabilitation of the dispossessed happen simultaneously. At this juncture, urban territories in the postcolonial context become sites where overlapping claims of territory ‘making’ and ‘unmaking’ by the postcolonial state and political society intersect. Here, urban territories are also sites for political society to operationalise a ‘politics of resistance’. However, analysing territories through such a framework has two major limitations.

Firstly, when we situate Chatterjee’s (Citation2011) theorisation in the context of postcolonial urban territories, it is often difficult to distinguish the boundaries between the state, civil, and political society. Here, neither the postcolonial state nor political society operates as a homogenous entity. It is further complicated when a part of civil society acts as a power broker between the state and political society, and others align themselves with political society. The management of internal tensions between ‘civil’ and ‘political society’ in the context of India represents an innovative mechanism of politics (Baviskar and Sundar Citation2008). They also state Chatterjee’s conception of ‘political society’ fails to identify the discourse of domination and their internal violence within a political society.

Secondly, to understand the process of territory ‘making’ in the postcolonial context, a binary framework of resistance vs dominance is inadequate. Here, resistance is the core subject of the state apparatus where resistance can also be viewed as an extension of power rather than challenging it (Sharp et al. Citation2000). In this case, power is constructed through social relations. It is the flow of social interactions which is mobilised through various networks (Allen Citation2009; Allen Citation2003). Political society in a postcolonial context is not always ready to tear through the hegemonic power through resistance. These acts are more contingent, repetitive, and habitual (Haynes and Prakash Citation1991). Simultaneously, the postcolonial state also makes political calculations about the demands of political society and selectively represents that as an exception to the norm.

The relationships between political society and the postcolonial state are not always representative of resistance; instead, they contain bargaining, negotiations, patronage, or sometimes direct antagonism. This does not undermine the importance of resistance as a form of engagement but portrays resistance as one of the forms which can be achieved through possibilities of rupture. At this juncture, the paper defines these engagements as conflict politics which is developed through networked mobilisation of power, the capacity of different actors, and opens up possibilities for analysing the dynamic trajectories of emancipation and social change (Featherstone Citation2008; Papaioannou Citation2014). Here, I borrow the idea of ‘friction’ to construct these engagements. For Tsing (Citation2005), ‘friction’ is represented by unstable, heterogeneous, awkward encounters that are developed through interconnections across different power relations. She states

As a metaphorical image, friction reminds us that heterogeneous and unequal encounters can lead to new arrangements of culture and power (Tsing Citation2005, 5).

Following her arguments, this paper conceptualises territories as not just edges; instead, they are the zones that are still unplanned and unmapped (Tsing Citation2005). They portray multiple spatiotemporal subjectivities where new relations are formed, which destabilise the boundaries between legality and illegality. The paper also argues territories are imaginative projects, a space of desire, a space of encounters for the enactment of multiple categorisations, and instability is persisted. It is a space whose recognition is still waiting and ‘dialectics at a standstill’ (Roy Citation2011).

Thus, this paper defines urban territories as an unstable category that continuously undergo alterations based on heterogeneous socio-spatial relations. They also constantly destabilise orderly state arrangements and reproduce certain modes of ‘order and lawmaking’ (Das and Poole Citation2004). From a decolonising perspective, territories portray a complex and ambiguous relationship between the state, political, and civil society. These are similar to what Yiftachel (Citation2009a) mentions as ‘grey spaces’. They are grey because they are always positioned between ‘whiteness of legality’ and ‘blackness of evictions and dispossession’ (Yiftachel Citation2009b, Citation2009a). There is always a pseudo-permanent existence of territory through ‘quiet encroachment of the ordinary’ (Bayat Citation2004). These understandings of territories also make them dynamic because of the instability of social category, their unpredictability, precariousness, and discursiveness (Tsing Citation1994; Simone Citation2007). Here, the practices are subtle; otherness is familiar but stays at a distance. There is an opacity that serves useful purposes for the state and capitalism (Gidwani and Maringanti Citation2016). This ambiguity serves a twofold aim. It helps the postcolonial state to promote capital accumulation without being fully registered, and it also promotes a selective allowance of rights for political society. The section on Contextualising Territories in Salt Lake further discusses this nature of territories with empirics.

Following this alternative framing of urban territories and associated conflict politics, the following section contextualises the study in Salt Lake, Kolkata, and discusses the methodology adopted for the study.

Contextualising territory in Salt Lake, Kolkata

To illustrate the above conceptual framework, I draw on an ethnographic study that I completed in Kolkata as part of my doctoral research (2016–2020). Kolkata as a site offers a unique understanding of the making and remaking of territories and their associated politics. As the colonial capital during the British rule, Kolkata portrays various conditions of postcoloniality where an ‘unfinished past’ shapes, modifies, and challenges the project of an ‘unstable present’ (Raghuram, Noxolo, and Madge Citation2014). Hence, urban territories in the context of Kolkata always represent this tension. Additionally, West Bengal is a state ruled by one of the longest-serving communist governments in the world for 34 years (1977–2011). Kolkata, being the capital of the state, was a bastion for the left for these 34 years and simultaneously reflected the paradoxical nature of left politics that is deeply entangled with the territorial control of the urban. Finally, my own personal attachment with Kolkata situates me within the zones of familiarity. Simultaneously, my continuous displacement from the city also allows me to navigate through these territories of familiarity with a ‘deliberate alienation’.

This study is situated in the township of Salt Lake in Kolkata, which was developed as a satellite township during the 1970s by reclaiming land from a lake nearby. The area was developed by following the modern town planning model of the garden city. The objective was to create a ‘humane and healthy environment, which would operate just like garden city’ (Rumbach Citation2017, 786). Initially, Salt Lake attempted to accommodate the post-partition ‘refugee’ influx from Bangladesh. From the late 1980s, the political economy of the area started changing. Salt Lake started flourishing as an alternative nucleus of the Central Business District (CBD) of Kolkata. This was coupled with the growth of the IT industry, and Salt Lake became a prime location for many IT companies along with several government offices. This also helped the flourishing informal economy in Salt Lake for construction workers, hawkers, household helps, and drivers. Present-day Salt Lake is dominated by gated communities, comparatively well-maintained streets, and urban amenities with upper-middle class and upper-class populations. It is also a preferred choice for many bureaucrats, retired judges, and other high-ranked government officials. Land ownership lies with the urban development department of the West Bengal state, where they lease out or allot plots as per requirements.

There is a complete absence of notified slumsFootnote2 in this area as the state government is never willing to institutionalise ‘informal settlements’. The informal settlements exist as squatter settlements, commonly known as ‘juggi jhopdi’. Squatter settlements not being addressed in the state or central government’s policy documents make them vulnerable to evictions. The fieldwork suggests that Salt Lake has approximately 15–20 squatter settlements with varied size ranges from 15 families to 150 families.

In Salt Lake, labour and its mobilisation as a resource for both state control and counter to it is of a gendered nature. The women labour force of squatters provides the service of domestic help, whereas the men labour force is engaged in hawking, involvement in paratransit transportation modes, casual construction workers, mechanics, and small shop owners. The squatter dwellers are mostly urban migrants from rural areas, and some of them are ‘illegal’ migrants from the neighbouring country Bangladesh. As most squatter dwellers are ‘migrants’ in Salt Lake, it causes varied territorial claims on the space that are often conflictual. For elite groups, all squatter dwellers are ‘illegal’ in Salt Lake and construct a narrative that limits their territorial claims. Simultaneously, among squatter dwellers, the tension between Bangladeshi migrant dwellers and non-Bangladeshi dwellers is often visible where non-Bangladeshi dwellers claim the other group’s claim as illegitimate. This shows how Salt Lake has become a contested territory for the state and elite groups and within political society, which is elaborated on in the following section.

Conflict politics in Salt Lake and contested territories ‘in making’

This paper focuses on contested territorial claims and associated conflict politics following the eviction of squatter settlements and hawkers in Salt Lake in 2017 (see ).

By bringing empirics from the anti-eviction movement of squatter dwellers, the paper also exhibits how ad hoc territorial claims were manifested through conflict politics.

The empirics come from ethnographic fieldwork from October 2017–March 2018. It adopts semi-structured interviews, participant observations, and oral history as methods for data collection. Almost 15 people were interviewed: squatter dwellers, community mobilisers, local councillors, elite group activists, and student activists. The study also uses visual materials from photography, newspaper reports, and posters/pamphlets to triangulate various claims by both the postcolonial state and the political society. The ethnographic study followed research ethics guidelines of the Open University involving human participants (Approval No. HREC/2530/Ray) and only used pseudonyms for the anonymisation of respondent’s identity.

The eviction of Salt Lake squatters started in October 2017. The postcolonial state used the trope of ‘clean and green city’ imagery to rationalise the eviction and organise the under-seventeen football word cup (FIFA U-17). The chronology of events is described in the following table (see ).

Table 1. Chronology of events in Salt Lake.

shows that the municipality stopped the eviction drive after 5 months. As a state apparatus, the Bidhannagar Municipal Corporation was fully aware that complete eviction was not possible, as it would cost them politically in elections. However, the state continued to intimidate squatter dwellers with threats of eviction. Finally, after completing the U-17 World Cup, the municipal corporation finally dropped the eviction plan as they realised it could cost them in the upcoming election. However, they continued to weaken the solidarity of the squatter dwellers by instigating a feeling of an outsider in reference to the Bangladeshi immigrants. In my conversation with Rajesh, a community mobiliser for the anti-eviction movement states

We need to make these people straight. The municipality people said if we want to stay here, there should not be any dirt. Also, these people pile up all the scraps here. So, for them, we can’t make ourselves vulnerable to evictions.

This shows how the state attempts to create a divide within the community. The logic of ‘otherness’ among squatter dwellers helps the state to rationalise eviction. The state used the same logic to mobilise elite groups of Salt Lake in support of eviction. This example shows that the political society is not a homogeneous group and the inner violence which exists within the political society for territorial claims. The state that operationalised violence through earlier evictions to gain territorial control became reluctant about the eviction after the completion of the World Cup. Through its ambiguous deployment of eviction drive, the postcolonial state creates elusive imagery of violence and simultaneously positions them as oppressors and saviours.

Practice of conflict politics and contesting territorial claims

Anti-eviction politics in the Indian context is often theorised as resistance against state oppression. However, my ethnographic fieldwork during the eviction drive in Salt Lake provides an alternative framework to analyse anti-eviction politics. Various forms of territorial claims are manifested in Salt Lake by the political society, the postcolonial state, and the elite groups or civil society. I outline these territorial claims below.

Anti-eviction conflict politics by political society

The strange case of clientelism: Clientelism can be explained as an exchange between patrons and his/her supporters when supporters receive some favour from the patrons for their contingent support (Berenschot (Citation2018). However, in Salt Lake, clientelism operates somewhat differently. When the eviction occurred, one squatter settlement could get a temporary rehabilitation by negotiating with the municipality contractor. The contractor occupied another public land and created ‘temporary’ shelters for the evicted dwellers of one squatter (see ).

The contractor gave permission to reside in another occupied site for 3 years to the already evicted dwellers, and the allocation followed a formal identity verification procedure, whereas at the same time, other squatters got evicted.

This selective allowance of the reappropriation of space happens for two reasons. Firstly, as the municipality contractor is part of the power network of the municipal corporation, legitimacy is allowed. Secondly, the rehabilitated dwellers act as a pool of casual labour force for the construction work owned by the municipality contractor. This shows an example of a quasi-permanent or ad hoc form of patronage. Here, patronage does not operate in the exchange of votes (as most of their voting rights are not within this electoral constituency). For the dwellers of the other squatters, neither are they part of any political network nor do they serve the purpose of the casual labour force. Hence, the selective legitimacy of the squatters. In my conversation with Ram, one of the dwellers who received the temporary allocation states

The contractor used to stay with us in that ground. We slum dwellers used to do his work. He is a contractor of the municipality. He has only assured us that we would get some space and some houses are getting constructed. Then we got the news that some houses are getting constructed here.

This shows why Ram got an allotment in the newly built houses after the eviction, whereas many others did not get that. This example helps us to depart from a normative understanding of clientelism in South Asia, which sees this as a failure of the state institutions and happens only to get political favours (in terms of votes) (Berenschot Citation2018, Citation2010). However, the Salt Lake case shows it operates slightly differently. Firstly, the postcolonial state did not participate directly with clientelism; rather, its apparatus (here the municipal contractor) facilitated clientelism for an economic reason to continue with the supply of cheap labour force. Secondly, it also critiques the idea of inadequacy of postcolonial governance. It argues that historically constructed multiple subjectivities of the state institutions cannot be seen as malfunctioning of it in the postcolonial world. It rather consciously opts to maintain certain loopholes for political mobilisation, which are necessarily not limited to electoral gains. This is evident in my conversation with the local councillor. She states

These shanty dwellers are not my voters. I don’t need to have any rapport with them. I think it important to have contact with the educated people of Salt Lake. They are my voters, who can understand me, I also need to understand them. So, it’s more important to keep in touch with them. I do that only.

As urban migrants, squatter dwellers do not have any voting rights for the local municipal elections in Salt Lake. Hence, the rationale of the electoral gain would not work here, and the postcolonial state manoeuverers its ad hoc mechanisms to establish an elusive territorial claim.

(b) ‘Quiet spaces of encroachment’: ‘Quiet spaces of encroachment’ is how squatter dwellers expand their already occupied spaces to accommodate their increasing family size (Bayat Citation2004). In my interview with squatter dwellers, they say that the gradual encroachment enables them to exert their rights on territories more prominently by occupying more space. This is evident in my conversation with a squatter dweller Suresh.

We expand our houses based on the number of family members. We always had two houses. Three of my siblings are in one house and our parents in another one. After everyone got married, we expanded to a third one. You just need to arrange the construction materials to expand. No one opposes as everyone follows the same. When your family grows, you expand a part of your house by occupying the adjoining area.

Suresh later says that occupying more space gives them a sense of security against any eviction. He also thinks that encroachment of a larger area can establish his claims for a larger space if there is any rehabilitation plan in future. Here, occupation not only happens as an organic process but is also directly linked with their territorial claims and gives a sense of security from their precarious conditions. These expansions do not follow any legal process and are done in an ad hoc manner by occupying adjacent area. The next section demonstrates another form of territorial claims which came out during the eviction by civil society, i.e., elite groups.

Elite resistance to support eviction

The elite groups supported the eviction to establish their territorial claims of a sanitised urban space. A poster was put up in Salt Lake by Citizens’ Forum to support the eviction for the beautification of Salt Lake (see ).

The poster says

We as taxpayers have a right to live in a clean & pollution free surrounding …. Bidhannagar is ours and we not only have a duty but also a right to protect it from becoming an unplanned, dirty and chaotic township. (Sic.)

This illustrates a particular discourse of rights by the elites where dirt and planning are used as tools for exclusion that promote a neoliberal logic of bourgeois environmentalism (Baviskar Citation2006). Citing Mary Douglas (1966), Barcan (Citation2010) argues that the metaphor ‘dirt’ symbolically signifies a ‘polluting agent’, which destabilises various socio-cultural categories (Barcan Citation2010). She also states that the idea of sanctity as a metaphor is used to ‘eliminate, conceal and purify’ and to preserve the order. The interview transcript from the elite group activist from Citizen Forum identifies this:

Squatter dwellers work as domestic help. But that necessarily does not mean they can stay here. They can stay in some cheap places like Mukundapur and other areas. My help comes from Mukundapur. Working in my house does not mean they can occupy any space they want. I think no illegal occupants should get any rehabilitation. If that is the case, people would come here, occupy any space for two to three years and then ask for rehabilitation. That is not possible.

This narrative that the elite group mobilises also highlights how territorial claims are contested. The elite groups deploy a neoliberal logic to eliminate any territorial claims by political society and essentialise the logic of bourgeois environmentalism to support evictions. The Citizen’s forum filed a case in the National Green Tribunal to clean the canal with the logic of sustainability. They also campaigned in support of eviction for a ‘Clean and Green Salt Lake’ and conducted a series of meetings with the Mayor and submitted a Detailed Project Report to make Salt Lake ‘liveable’.

The Mayor of Bidhannagar Municipal corporation expressed his support in favour of this campaign and stated: ‘black plastics should be removed from Salt Lake’. Here black plastic is a metaphor used to indicate the squatter dwellers as they use plastic sheets for roofing. This metaphor also signifies how the state creates vocabularies of exclusion at the cost of ‘dehumanising’ the shanty dwellers. Here, people are only represented as unholy (black as a colour) objects, and the state justifies evictions. The Mayor’s support for civil society activism also indicates how the state in an illegible form operationalises metaphors of exclusion. Subsequently, the state and civil society get intermingled in such a form where it is difficult to identify them separately.

The Salt Lake eviction case demonstrates the postcolonial state’s direct involvement in the process of eviction and violence. Here, the state represents both the local authority (Municipal Corporation) and the regional state (West Bengal). At both levels, the state is represented by the same political party. Here, civil society (represented by elite resistance) co-opts the state and argues in favour of civility. Here, political society (squatter dwellers) faces a double articulation of hegemony, through the state and civil society. Though they counter the state through various ways of conflict politics, their counter-resistance to civil society activism is minimal. This has two reasons. Firstly, political society’s direct dependence on civil society for everyday economic purposes (house help, driver, etc.). Secondly, hegemonic appropriation by civil society is often overlooked because of its contingent nature. The above discussion about conflict politics in Salt Lake also highlights the multiplicity of relationships between the state and political society. Political society is not only subject to state domination nor is it able to change its precariousness radically. Their conflict politics practice depends on available resources (political capital), the nature of state oppression, and the involvement of civil society. In the following section, the paper maps the power network in Salt Lake, which was used for eviction and to counter that.

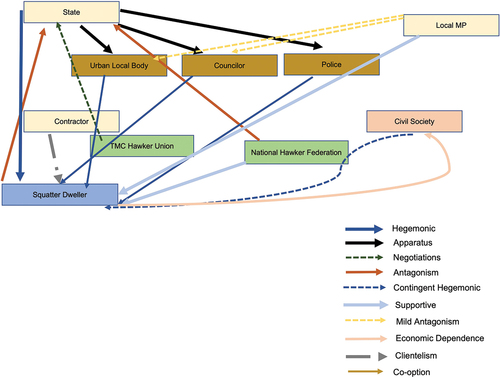

Power networks in Salt Lake

In the case of Salt Lake, the state is directly involved in the eviction and maintains a hegemonic relation with political society (squatter dwellers). It operationalises its hegemonic power through apparatuses like the police and the urban local body (see ), whereas political society is antagonistic to the state. However, the local Member of Parliament (MP) (also part of the state and the same political party) is sympathetic to their demands, and they support him. Here, political society navigates within the power networks of the state apparatus and capitalises on the conflict between different lobbies of the same political party. On the other hand, civil society co-opts with the urban local body and supports the evictions. As the political society is economically dependent on civil society for job opportunities (driver, house help), they are not apparently antagonistic to civil society. As discussed above, the municipality contractor plays a vital role in clientelism (ibid. 13, 14). He plays a role of a power broker between the state and political society and selectively accommodates some territorial claims by political society (see ).

Outcome of conflict politics

The anti-eviction movement in Salt Lake does not have any specific outcome in general. The partial rehabilitation in a state-sponsored occupation was not a direct result of the movement. However, the movement managed to portray resistance to state violence and established the recognition of their rights over territories. Currently, there is no immediate eviction threat. But minimising eviction threat cannot be considered the outcome of the movement. The state already knew they could not evict people completely, but as there was the global event of the U-17 world cup, for the time being, they wanted to ‘clean’ the city. After the world cup, things went back to ‘normal’. It shows how eviction and counter to it operate through an ad hoc form of ‘permanent temporariness’ in the postcolonial context of Kolkata.

This highlights two things. First, territorial claims for political society are always ambiguous and entangled with precarity and violence. It coexists with their resistance to the state and partial recognition of their claims. Second, the discursive nature of territories is better understood through everyday occupation and autonomy, which create a discursive political field with various political imaginations. This is an alternative habitus for the enactment of rights, access to urban resources and solidarity. By citing Gould (2009), Vasudevan (Citation2015) states that the alternative habitus provides a common spatial field where body, sentiments, ideas, values, and practices operate and create a shared sense of inhabitation and modes of being (Vasudevan Citation2015). Here, territories demonstrate a spatial field that enables the postcolonial state to recognise the rights of political society. Simultaneously, the state also feels threatened by political society for their political survival. Based on this discussion, the next section of the paper develops a framework of spatial adhocism, which helps to theorise territories from ‘elsewhere’.

Spatial adhocism in territories

The above examples of differential territorial claims in the anti-eviction movement in Salt Lake show how territories are dynamic spatial entities, constantly contested through heterogeneous relationships between the state, political society, and civil society. This also shows how territories are reconfigured through networked mobilisation of power and promoting the allowance of a selective right for political society. The postcolonial state utilises territories to establish its own claims of discipline and dominance and to create an image of a global city by subsequently disenfranchising political society. Simultaneously, the state also utilises territories for selective allowance of rights for political society, enabling its risk-taking abilities for political legitimacy (Papaioannou Citation2020).

The evicted dwellers who received partial rehabilitation (ibid 13, 14) were allocated based on the identity documents of the squatter dwellers. Many squatter dwellers are migrants in the Salt Lake area and do not have a permanent address. It is also interesting to see how they acquire an identity document that mentions a Salt Lake address. When I asked one of the dwellers, Bapi, he said:

We use the petrol pump’s address as proof of address for our home. We have acquittances in the nearby petrol pump. We used that address to make our Aadhaar cards.

Bapi lives in the shanty near Rabindra Okakura Bhavan in Salt Lake. Like many other dwellers, Bapi also migrated to Kolkata from a village. Bapi cannot furnish his proof of address in the city like others. Without this proof of address, Bapi cannot make an identity document in the city, which makes any kind of municipal or state services inaccessible for him, and he is also devoid of being part of any rehabilitation proposal in future. This situation compelled Bapi to acquire a Kolkata address which he acquired through an ‘ad hoc’ way. He mobilised his social capital and furnished the address of the nearby petrol pump to get his Aadhaar card. He can also navigate (through clientelism and bargaining, discussed in the previous section) across different power networks to claim his urban citizenship in Salt Lake through his acquired Aadhaar card.

Here, the Aadhaar card becomes an apparatus for Bapi’s territorial claims, without which his claims for urban citizenship would not be validated. On the other hand, this Aadhaar card provides him partial legitimacy to stay in the squatter and also provides him with the opportunity to at least claim the right to rehabilitation after an eviction, even for the temporary time being. Bapi and other residents of that squatter talked about how the police, during the eviction, asked for a copy of their Aadhaar cards to prove that they were not ‘Bangladeshi immigrants’.

For Bapi and many others like him, their territorial claims are dependent on an ambiguous form of alternative governmentality (Srivastava Citation2012). This enables Bapi to navigate across different networks while also enabling the postcolonial state to re-establish its discipline and domination on the subjects living in urban margins. Bapi’s adaptation of adhocism results from the urgency of his situation and an attempt to appropriate his spatiality. His spatiality is an unfinished project which continuously transcends the fixity of space. This spatiality creates taxonomies of spatiality between real and narrated addresses.

My interactions in other squatter settlements of Salt Lake reveal that (il)legal ‘Bangladeshi migrants’ also manage to get Aadhaar cards. However, in my conversations with the squatter dwellers, no one identifies themselves as Bangladeshis, but some co-residents vaguely indicate a group as ‘Bangladeshi migrants’. So, having an Aadhaar card partially legitimises their presence in that territory, even if they are settling in an ‘illegitimised’ colony or as an ‘illegal’ migrant. The Aadhaar card provides Bapi and other Hindu residents with a perceived sense of security while creating a sense of otherness imposed on the ‘Bangladeshi migrant’. These examples for acquiring a document (here Aadhaar card) happen in a quasi-legal way, and often, the state promotes these quasi-legal processes. This paper defines them as spatial adhocism.

Spatial adhocism as a practice is certainly innovative (as shown in Bapi’s case) as it has the potential to alter hegemonic socio-spatial relationships. Simultaneous spatial adhocism also symbolises precariousness and subtle violence. Spatial adhocism sometimes reduces the chance of engagement in conflict politics for the people in the urban territories because of its subtle nature. Bapi’s example shows that spatial adhocism becomes a circulatory field of various forms of practices and relationships, spatial reappropriation, and power structures. Sometimes they are hierarchical, sometimes they are counter-hegemonic, and sometimes they become a constitutive form of the fluid identity of the postcolonial state and political society.

Ram states that those who could not furnish their Aadhaar card after eviction did not get this temporary housing. Ram is also aware of his precariousness as these houses are only provided for 3 years. For Ram, sites of eviction and rehabilitation both become what Sanyal (Citation2018) calls ‘zones of waiting’. She sees these zones as the intersection of precariousness and possibilities (Sanyal Citation2018).

For Ram, waiting becomes a spatial subjectivity of precariousness, hope, and violence like many others. Waiting also enables Ram to express his desire for urban citizenship qualification, access to urban resources, and exert his claims for territory. But simultaneously, this waiting also symbolises his continuous disenfranchisement from the process of exerting his rights over urban space.

At this juncture, adhocism is constructed through mobility and mutability rather than specificity (Gaonkar and Povinelli Citation2003). Mutability as a form of spatial appropriation squatter dwellers of Salt Lake occupy and encroach spaces (ibid 15). They get rehabilitated after eviction in another state-sponsored occupied space. For some squatter dwellers, the selective acknowledgement of their territorial claims, even for a limited time, helps them to navigate various power networks. The subtle encroachment of the ordinary, the temporary allocation of houses for some evicted dwellers, and forging a petrol pump’s address to acquire identity documents (ibid 19) become important vignettes for their mobility and mutability.

Towards an alternative framework

The above discussion on spatial adhocism and its various examples indicate three unique characteristics of spatial adhocism. Firstly, it acts as what Strauss and Calude (Citation1962) have called ‘bricoleur’ (bricolage). For him, ‘bricoleur’ is the performance of diverse activities in a non-hegemonic structure (Strauss and Calude Citation1962). In the case of Salt Lake, adhocism arises from urgency and reappropriation. The element of urgency is not an impromptu, ambiguous solution, but rather a strategic mechanism operationalised through everyday repetitive and habitual practices of different actors and networks of power. The reappropriation of space happens through negotiations, violence, and compromises where it becomes a ‘sphere of multiplicity’ and it is relational (Massey Citation2005).

Secondly, empirics of spatial adhocism show that the assemblage is always purposeful and ‘deliberate realisation of a distinctive plan’ (Buchanan Citation2015). Various authors establish that assemblage is a new becoming, a constellation of materials and actions, and forms of heterogeneous relations (Bennett Citation2004; Anderson and McFarlane Citation2011). Here, spatial adhocism becomes a discursive politics enacted through assemblage. Here, the assemblage is relational and generative and operates within urban territories of the postcolony in a complex way. It is relational for two reasons. Firstly, a certain autonomy exists with each of the elements. Secondly, adhocism allows continuous flows of objects, actions, and power (Müller Citation2015). It is generative because it always seeks territorialisation and deterritorialisation, which is visible in the empirics of how adhocism operates through the state, through people at the margins (Legg Citation2009).

Finally, spatial adhocism is omnipresent in urban territories in Kolkata and is not only restricted to political society but the state also adopts ad hoc practices. Hence, spatial adhocism becomes the methodological apparatus through which urban territories can be theorised.

Conclusion

This paper discusses the empirics of conflict politics and spatial adhocism for an alternative understanding of urban territories. On the one hand, conflict politics helps us to understand how contested territorial claims are operationalised by the postcolonial state and political society. On the other hand, the framework of spatial adhocism shows how these territorial claims are spatially manifested, which unsettles any defined category of territories as they are continuously in the process of making and remaking. It rejects any fixity of categories but encourages an iterative process for theorisation. The examples of adhocism in Salt Lake highlight categories are multiple but incomplete. They are incomplete because of their untranslatability, dynamicity, and urgency. Spatial adhocism is emergent because of its ‘creative unpredictability’he examples of emergence show how new socio-spatial relations are formed through clientelism in the case of Salt Lake. Simultaneously, it is indeterminate because several actors engage in an uneven topography of power, where sometimes they counter each other, sometimes transact with each other, or sometimes assimilate.

Conceptually, spatial adhocism proposes two formations. Firstly, it attempts to destabilise the formation of law as a normative apparatus. On the one hand, the squatter dwellers acquire addresses for Aadhaar cards in a ‘quasi-legal’ way, and simultaneously they get evicted for ‘illegal’ occupation of lands. Secondly, it also challenges the idea of ‘malpractice by the postcolonial state’. Here, spatial adhocism unsettles the idea of ‘malpractice’ and makes that a constitutive category of the postcolonial state. Here, ‘malpractice’ cannot be read as a failure of the institutions; rather, it establishes ‘malpractice’ as a self-defence mechanism for the postcolonial state to establish its territorial claims and selectively legitimise certain claims by political society. For the state, this self-defence mechanism enables them to overlook the legal status of occupation and also helps them to sponsor rehabilitation of the evicted dwellers in another occupied land. For a political society, using a ‘false’ address for Aadhar card and simultaneously establishing their territorial claims through it formulate a fluid socio-spatial subjectivity. Hence, spatial adhocism continuously constructs categories and simultaneously disassociates itself from those categories. It creates social imagery of being in a fluid middle ground where categories are ‘yet to be built’, an alternate future muddled up with uncertainty, a language, as Simone (2004) insists, is yet to develop; a future that is ‘yet to come’.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Theo Papaioannou, Parvati Raghuram, and Philipp Horn for their valuable comments and feedback during my doctoral studies. I would also like to thank David Featherstone, who continuously helped with comments and reviewing the paper. Thanks are due to the guest editor of the special issue Sam Halvorsen and two anonymous reviewers who helped in sharpening the paper with their generous comments. Finally, I would also like to thank my respondents who spent adequate time with me during my fieldwork.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Raktim Ray

Raktim Ray is a Lecturer (Teaching) at the Bartlett Development Planning Unit, University College of London. He has an interdisciplinary background in International Development, Urban Planning and Geography. He has professional experience working in various forms of institutions from private companies to civil society organisations in India. His PhD in International Development from The Open University, UK, was focused on how people at the urban margins of Kolkata, India, engage with the postcolonial state through various forms of conflict politics. His current research focuses on two themes: a) politics of care during and solidarity networks and b) infrastructure for resistance.

Notes

1. Only pseudonyms have been used.

2. Notified Slum is a state-identified legal status of a slum.

References

- Allen, J. 2003. Lost Geographies of Power. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

- Allen, J. 2009. “Three Spaces of Power: Territory, Networks, Plus a Topological Twist in the Tale of Domination and Authority.” Journal of Power 2 (2): 197–212. doi:10.1080/17540290903064267.

- Anderson, B., and C. McFarlane. 2011. “Assemblage and Geography.” Area 43 (2): 124–127. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4762.2011.01004.x.

- Barcan, R. 2010. “Dirty Spaces: Separation, Concealment, and Shame in the Public Toilet.” In Toilet: Public Restrooms and the Politics of Sharing, edited by H. Molotch and L. Noren. New York and London: New York University Press. 25–42.

- Baviskar, A. 2006. “Demolishing Delhi : World Class City in the Making.” Mute 5: 1–5.

- Baviskar, A., and N. Sundar. 2008. “Democracy versus Economic Transformation?” Economic and Political Weekly 43 (46): 87–89.

- Bayat, A. 2004. “Globalization and the Politics of the Informals in the Global South.” In Urban Informality: Transnational Perspectives from the Middle East, Latin America, and South Asia, edited by A. Roy and N. Alsayyad, 192–247. Oxford: Lexington Books.

- Bennett, J. 2004. “The Agency of Assemblages and the North American Blackout.” Public Culture 17 (3): 445–465. doi:10.1215/08992363-17-3-445.

- Berenschot, W. 2010. “Everyday Mediation: The Politics of Public Service Delivery in Gujarat, India.” Development and Change 41 (5): 883–905. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7660.2010.01660.x.

- Berenschot, W. 2018. “The Political Economy of Clientelism: A Comparative Study of Indonesia’s Patronage Democracy.” Comparative Political Studies 51 (12): 1563–1593. doi:10.1177/0010414018758756.

- Buchanan, I. 2015. “Assemblage Theory and Its Discontents.” Deleuze Studies 3 (1): 382–392. doi:10.3366/dls.2015.0193.

- Chatterjee, P. 2004. “The Politics of the Governed: Reflections on Popular Politics in Most of the World.” In The Politics of the Governed: Reflections on Popular Politics in Most of the World. New York: Columbia Univerity Press. 53–80.

- Chatterjee, P. 2011. Lineages of Political Society: Studies in Postcolonial Democracy. New York: Columbia Univerity Press.

- Cochrane, A., and K. Ward. 2012. “Researching the Geographies of Policy Mobility: Confronting the Methodological Challenges.” Environment & Planning A 44 (1): 5–12. doi:10.1068/a44176.

- Das, V. 2004. “The Signature of the State – The Paradox of Illegibility.” In Anthropology in the Margins of the State, edited by V. Das and D. Poole, 225–252. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Das, V., and D. Poole. 2004. “State and Its Margins: Comparative Ethnographies.” In Anthropology in the Margins of the State, edited by V. Das and D. Poole, 3–33. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Elden, S. 2010. “Land, Terrain, Territory.” Progress in Human Geography 34 (6): 799–817. doi:10.1177/0309132510362603.

- Featherstone, D. 2008. Resistance, Space and Political Identities: The Making of Counter-Global Networks. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell.

- Gaonkar, D. P., and E. Povinelli. 2003. “Technologies of Public Forms: Circulation, Transfiguration, Recognition.” Public Culture 15 (3): 385–398. doi:10.1215/08992363-15-3-385.

- Gidwani, V., and A. Maringanti. 2016. “The Waste-Value Dialectic.” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 36 (1): 112–133. doi:10.1215/1089201x-3482159.

- Gieseking, J. J. 2016. “Crossing over into Neighbourhoods of the Body: Urban Territories, Borders and Lesbian-Queer Bodies in New York City.” Area 48 (3): 262–270. doi:10.1111/area.12147.

- Halvorsen, S. 2019. “Decolonising Territory: Dialogues with Latin American Knowledges and Grassroots Strategies.” Progress in Human Geography 43 (5): 790–814. doi:10.1177/0309132518777623.

- Halvorsen, S., B. Mançano Fernandes, and F. Valeria Torres. 2019. “Mobilizing Territory: Socioterritorial Movements in Comparative Perspective.” Annals of the American Association of Geographers 109 (5): 1454–1470. doi:10.1080/24694452.2018.1549973.

- Haynes, D., and G. Prakash. 1991. “Introduction: The Entanglement of Power and Resistance.” In Contesting Power- Resistance and Everyday Social Relations in South Asia, edited by D. Haynes and G. Prakash, 1–22. Berkeley, Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- Hughes, S. S. 2020. “Unbounded Territoriality: Territorial Control, Settler Colonialism, and Israel/Palestine.” Settler Colonial Studies 10 (2): 216–233. doi:10.1080/2201473X.2020.1741763.

- Ince, A. 2012. “In the Shell of the Old: Anarchist Geographies of Territorialisation.” Antipode 44 (5): 1645–1666. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8330.2012.01029.x.

- Jessop, B. 2012. “The State.” In The Elgar Companion to Marxist Economics, edited by B. Fine, A. Saad-Filho, and M. Boffo, 330–340. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Legg, S. 2009. “Of Scales, Networks and Assemblages: The League of Nations Apparatus and the Scalar Sovereignty of the Government of India.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 34 (2): 234–253. doi:10.1111/j.1475-5661.2009.00338.x.

- López, M., and Claudia. 2020. “Contesting Double Displacement: Internally Displaced Campesinos and the Social Production of Urban Territory in Medellín, Colombia.” Geographica Helvetica 74 (3): 249–259. doi:10.5194/gh-74-249-2019.

- Mason-Deese, L., V. Habermehl, and N. Clare. 2020. “Producing Territory: Territorial Organizing of Movements in Buenos Aires.” Geographica Helvetica 74 (2): 153–161. doi:10.5194/gh-74-153-2019.

- Massey, D. 2005. For Space. London: Sage Publications .

- Müller, M. 2015. “Assemblages and Actor-Networks : Rethinking Socio-Material Power, Politics and Space.” Geography Compass 27 (41): 27–41. doi:10.1111/gec3.12192.

- Osuri, G. 2017. “Imperialism, Colonialism and Sovereignty in the (Post)colony: India and Kashmir.” Third World Quarterly 38 (11): 2428–2443. doi:10.1080/01436597.2017.1354695.

- Painter, J. 2010. “Rethinking Territory.” Antipode 42 (5): 1090–1118. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8330.2010.00795.x.

- Papaioannou, T. 2014. “How Inclusive Can Innovation and Development Be in the Twenty-First Century?” Innovation and Development 4 (2): 187–202. doi:10.1080/2157930X.2014.921355.

- Papaioannou, T. 2020. “Reflections on the Entrepreneurial State, Innovation and Social Justice.” Review of Evolutionary Political Economy 1 (2): 199–220. doi:10.1007/s43253-020-00018-z.

- Raghuram, P., P. Noxolo, and C. Madge. 2014. “Rising Asia and Postcolonial Geography: A View through the Indeterminacy of Postcolonial Theory.” Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography 35 (1): 119–135. doi:10.1111/sjtg.12045.

- Roy, A. 2011. “The Agonism of Utopia : Dialectics at a Standstill.” Traditional Dwellings and Settlements Review XXIII (1): 15–24.

- Rumbach, A. 2017. “At the Roots of Urban Disasters: Planning and Uneven Geographies of Risk in Kolkata, India.“ Journal of Urban Affairs 39 (6): 783–799.

- Sanyal, R. 2018. “Managing through Ad Hoc Measures : Syrian Refugees and the Politics of Waiting in Lebanon.” Political Geography 66: 67–75. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2018.08.015. December 2016.

- Schwarz, A., and M. Streule. 2016. “A Transposition of Territory: Decolonized Perspectives in Current Urban Research.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 40 (5): 1000–1016. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.12439.

- Strauss, L. . 1962. “The Science of the Concrete.” In The Savage Mind, 1–22. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Sharp, J. P., P. Routledge, C. Philo, and R. Paddison. 2000. “Entanglements of Power: Geographies of Domination/ Resistance.” In Entanglements of Power: Geographies of Domination/Resistance, edited by J. P. Sharp, P. Routledge, C. Philo, and R. Paddison, 1–42. London and New York: Routledge.

- Sheppard E, Leitner H and Maringanti A. (2013). Provincializing Global Urbanism: A Manifesto. Urban Geography, 34(7), 893–900. doi:10.1080/02723638.2013.807977

- Simone, A. 2007. “At the Frontier of the Urban Periphery.” Sarai Reader 462–470 archive.sarai.net/files/original/e3366451a06d9bbe4187fac6a550ec91.pdf.

- Simone, A. M. 2020. “To Extend: Temporariness in a World of Itineraries.” Urban Studies 57 (6): 1127–1142. doi:10.1177/0042098020905442.

- Spivak, G. C. 2012. In Other Worlds: Essays In Cultural Politics. New York and London: Methuen.

- Srivastava, S. 2012. “Duplicity, Intimacy, Community: An Ethnography of ID Cards, Permits and Other Fake Documents in Delhi.” Thesis Eleven 113 (1): 78–93. doi:10.1177/0725513612456686.

- Stienen, A. 2020. “‘(Re)claiming Territory : Colombia’s Territorial-Peace.” Approach and the City’ 75 (3): 285–306. doi:10.5194/gh-75-285-2020.

- Tsing, A. 1994. “From the Margins.” Current Anthropology 9 (3): 153–279–97.

- Tsing, A. 2005. Friction: An Ethnography of Global Connection. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

- Vasudevan, A. 2015. “The Makeshift City: Towards a Global Geography of Squatting.” Progress in Human Geography 39 (3): 338–359. doi:10.1177/0309132514531471.

- Vinay, G., and R. N. Reddy. 2011. “The Afterlives of “Waste”: Notes from India for a Minor History of Capitalist Surplus.” Antipode 43 (5): 1625–1658. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8330.2011.00902.x.

- Yacobi, H., and E. Tzfadia. 2019. “Neo-Settler Colonialism and the Re-Formation of Territory: Privatization and Nationalization in Israel.” Mediterranean Politics 24 (1): 1–19. doi:10.1080/13629395.2017.1371900.

- Yiftachel, O. 2009a. “Critical Theory and “Gray Space”: Mobilization of the Colonized.” City 13 (2–3): 246–263. doi:10.1080/13604810902982227.

- Yiftachel, O. 2009b. “Theoretical Notes on “Gray Cities”: The Coming of Urban Apartheid?” Planning Theory 8 (1): 88–100. doi:10.1177/1473095208099300.