Abstract

Duchesnea chrysantha (Zoll. & Moritzi) Miq. is a traditional medicinal species of genus Duchesnea nested in Potentilla genus but having a significant key to be independent genus. In this study, we presented first complete chloroplast genome of D. chrysantha which is 156,329 bp long and has four subregions: 85,568 bp of large single copy (LSC) and 18,757 bp of small single copy (SSC) regions are separated by 26,002 bp of inverted repeat (IR) regions including 129 genes (84 protein-coding genes, 8 rRNAs, and 37 tRNAs). The overall GC content of the chloroplast genome is 37.0% and those in the LSC, SSC, and IR regions are 34.9%, 30.5%, and 42.8%, respectively. Phylogenetic trees show that D. chrysantha is clustered with D. indica and Duchesnea clade is nested in Potentilla clade with high bootstrap support.

Duchesnea chrysantha (Zoll. & Moritzi) Miq., belonging to genus Duchesnea, which is distinguished with genus Potentilla by morphological characteristics (Heo et al., under review) but is nested in Potentilla clade in molecular phylogenetic tree (Töpel et al. Citation2011; Feng et al. Citation2017), is an eatable species (Tanaka and Nakao Citation1976) and is different from Duchesnea indica by leaf shape and color (Chaoluan et al. 2003; Heo et al., under review). D. chrysantha has also similar fruit structure to genus Fragaria. Moreover, useful secondary metabolites of D. chrysantha have been reported which are effective for asthma (Yang et al. Citation2008), human cancer cells, (Lee and Yang Citation1994) pancreatic lipase inhibitory activities (Liu et al. Citation2012), and etc. Because genus Duchesnea consists of two species, we sequenced and analyzed complete chloroplast genome of D. chrysantha together with that of D. indica (Heo et al. 2019).

Total DNA of D. chrysantha collected in Japan (Voucher in InfoBoss Cyber Herbarium (IN); K-I. Heo, IB-00572) was extracted from fresh leaves by using a DNeasy Plant Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). Genome sequencing was performed using HiSeq2000 at Macrogen Inc., Korea, and de novo assembly was done by Velvet 1.2.10 (Zerbino and Birney Citation2008) and gaps were filled by SOAPGapCloser 1.12 (Zhao et al. Citation2011) and confirmed based on alignments by BWA 0.7.17 (Li Citation2013) and SAMtools 1.9 (Li et al. Citation2009). Geneious R11 11.0.5 (Biomatters Ltd., Auckland, New Zealand) was used for chloroplast genome annotation based on Duchesnea indica chloroplast complete genome (MK134678; Heo et al. 2019).

The chloroplast genome of D. chrysantha (Genbank accession is MK144666) is 156,329 bp and has four subregions: 85,568 bp of large single copy (LSC) and 18,757 bp of small single copy (SSC) regions are separated by 26,002 bp of inverted repeat (IR). It contained 129 genes (84 protein-coding genes, 8 rRNAs, and 37 tRNAs); 18 genes (7 protein-coding genes, 4 rRNAs, and 7 tRNAs) are duplicated in IR regions. The overall GC content of D. chrysantha is 37.0% and in the LSC, SSC, and IR regions are 34.9%, 30.5%, and 42.8%, respectively.

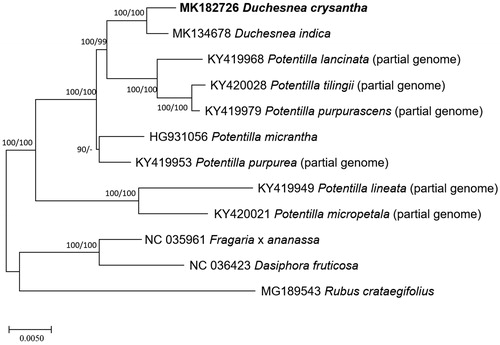

Six partial (Zhang et al. Citation2017) and one complete (Ferrarini et al. Citation2013) Potentilla, two Duchesnea (Heo et al. 2019; in this study), and three additional Rosaceae chloroplast genomes were used for constructing phylogenic trees. Whole chloroplast genome sequences were aligned by MAFFT 7.388 (Katoh and Standley Citation2013) for constructing neighbor joining (bootstrap repeat is 10,000) and maximum likelihood (bootstrap repeat is 1,000) trees using MEGA X (Kumar et al. Citation2018). Phylogenetic trees show that D. chrysantha is clustered with D. indica and Duchesnea clade is nested in Potentilla clade with high bootstrap support, agreeing with previous Potentilla phylogeny studies. (Eriksson et al. Citation1998; Eriksson et al. Citation2003; Töpel et al. Citation2011; Feng et al. Citation2017; ). In addition, all clades in Potentilla and Duchesnea genera are supported by high bootstrap values, also agreeing with previous studies (Eriksson et al. Citation1998; Eriksson et al. Citation2003; Töpel et al. Citation2011; Feng et al. Citation2017).

Figure 1. Neighbor joining (bootstrap repeat is 10,000) and maximum likelihood (bootstrap repeat is 1,000) phylogenetic trees of 12 Rosaceae partial or complete chloroplast genomes (Duchesnea chrysantha; this study, MK182726, Duchesnea indica (MK134678), Potentilla tilingii (KY420028; partial genome), Potentilla lancinata (KY419968; partial genome), Potentilla purpurea (KY419953; partial genome), Potentila purpurascens (KY419979; partial genome), Potentilla micropetala (KY420021; partial genome) Potentilla micrantha (HG931056; partial genome), Potentilla alineata (KY419949; partial genome), Potentilla lancinate (KY419968; partial genome), Dasiphora fruticosa (NC 036423), Fragaria x ananassa cultivar Benihoppe (NC_035961), and Rubus crataegifolius (MG189543). The numbers above branches indicate bootstrap support values of maximum likelihood and neighbor joining phylogenetic tree, respectively.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Chaoluan L, Ikeda H, Ohba H. 2003. Potentilla Linnaeus, Sp. Pl. 1: 495. 1753. In: Wu ZY, Raven PH, Hong DY, editors. Flora of China. Vol. 9. p. 291–327.

- Eriksson T, Donoghue MJ, Hibbs MS. 1998. Phylogenetic analysis of Potentilla using DNA sequences of nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacers (ITS), and implications for the classification of Rosoideae (Rosaceae). Plant Syst Evol. 211:155–179.

- Eriksson T, Hibbs MS, Yoder AD, Delwiche CF, Donoghue MJ. 2003. The phylogeny of Rosoideae (Rosaceae) based on sequences of the internal transcribed spacers (ITS) of nuclear ribosomal DNA and the trnL/F region of chloroplast DNA. Int J Plant Sci. 164:197–211.

- Feng T, Moore MJ, Yan MH, Sun YX, Zhang HJ, Meng AP, Li XD, Jian SG, Li JQ, Wang HC. 2017. Phylogenetic study of the tribe Potentilleae (Rosaceae), with further insight into the disintegration of Sibbaldia. J Syst Evol. 55:177–191.

- Ferrarini M, Moretto M, Ward JA, Šurbanovski N, Stevanović V, Giongo L, Viola R, Cavalieri D, Velasco R, Cestaro A, Sargent DJ. 2013. An evaluation of the PacBio RS platform for sequencing and de novo assembly of a chloroplast genome. BMC Genomics. 14:670.

- Heo K-I, Kim Y, Maki M, Park J. 2019. The complete chloroplast genome of mock strawberry, Duchesnea indica (Andrews) Th.Wolf (Rosoideae). Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 4:560–562.

- Katoh K, Standley DM. 2013. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol. 30:772–780.

- Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K. 2018. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across Computing Platforms. Mol Biol Evol. 35:1547–1549.

- Lee IR, Yang MY. 1994. Phenolic compounds from Duchesnea chrysantha and their cytotoxic activities in human cancer cell. Arch Pharm Res. 17:476–479.

- Li H. 2013. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. arXiv Preprint arXiv. 13033997.

- Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, Durbin R. 2009. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 25:2078–2079.

- Liu Q, Ahn JH, Kim SB, Hwang BY, Lee MK. 2012. Flavonoids constituents of Duchesnea chrysantha. Korean J Pharmacogn. 43:201–205.

- Tanaka T, Nakao S. 1976. Tanaka's cyclopedia of edible plants of the world.Tokyo, Japan: Yugaku-sha.

- Töpel M, Lundberg M, Eriksson T, Eriksen B. 2011. Molecular data and ploidal levels indicate several putative allopolyploidization events in the genus Potentilla (Rosaceae). PLOS Currents Tree of Life. Edition 1. doi: 10.1371/currents.RRN1237.

- Yang EJ, Lee J-S, Yun C-Y, Kim J-H, Kim J-S, Kim D-H, Kim IS. 2008. Inhibitory effects of Duchesnea chrysantha extract on ovalbumin-induced lung inflammation in a mouse model of asthma. J Ethnopharmacol. 118:102–107.

- Zerbino DR, Birney E. 2008. Velvet: algorithms for de novo short read assembly using de Bruijn graphs. Genome Res. 18:821–829.

- Zhang SD, Jin JJ, Chen SY, Chase MW, Soltis DE, Li HT, Yang JB, Li DZ, Yi TS. 2017. Diversification of Rosaceae since the Late Cretaceous based on plastid phylogenomics. New Phytologist. 214:1355–1367.

- Zhao Q-Y, Wang Y, Kong Y-M, Luo D, Li X, Hao P. 2011. Optimizing de novo transcriptome assembly from short-read RNA-Seq data: a comparative study. BMC Bioinformatics. 12:S2.