Abstract

Chenopodium ficifolium Sm. is an invasive weedy species, one of the main targets for weed control in Korea. In this study, we presented the first complete chloroplast genome of C. ficifolium which is 151,823 bp long and has four subregions: 83,668 bp of large single copy (LSC) and 17,937 bp of small single copy (SSC) regions are separated by 25,109 bp of inverted repeat (IR) regions including 129 genes (84 protein-coding genes, eight rRNAs, and 37 tRNAs). The overall GC content of the chloroplast genome is 37.3% and those in the LSC, SSC, and IR regions are 35.3%, 31.0%, and 42.7%, respectively. Phylogenetic tree shows that C. ficifolium is clustered with C. album forming a monophyletic clade with other Chenopodium species.

Chenopodium ficifolium Sm., an annual weed, is an invasive species originated from Europe (Park Citation2009). It is usually distributed in housing neighborhood, roadside, vacant lots, fields, orchard, and pasture, being one of 10 major invasive weed species and target species for weed control in Korea (Lee et al. Citation2017). It is not easily distinguished from Chenopodium album during early stage because leaf shape is similar to that of C. album; whereas it can be recognized clearly from C. album by (i) different fruiting season (April to July) earlier than that of C. album, (ii) tepals cover fruit even in fruiting season, and (iii) seed coat is reticular (Chung Citation1992; Kim and Kil Citation2017).

Due to lack of chloroplast genome sequences of C. ficifolium, we completed chloroplast genome of C. ficifolium isolated in Taean-gun, Chungcheongnam province, Korea (Voucher in InfoBoss Cyber Herbarium (IN); YS. Kim, IB-00576). Total DNA of C. ficifolium was extracted from fresh leaves using a DNeasy Plant Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). Genome sequencing was performed using HiSeqX at Macrogen Inc., Korea. de novo assembly was done by Velvet 1.2.10 (Zerbino and Birney Citation2008) and SOAPGapCloser 1.12 (Zhao et al. Citation2011) and confirmed based on alignments generated by BWA 0.7.17 (Li Citation2013) and SAMtools 1.9 (Li et al. Citation2009). Geneious R11 11.1.5 (Biomatters Ltd., Auckland, New Zealand) was used for chloroplast genome annotation based on C. album chloroplast complete genome (NC_034950; Wang et al. Citation2017).

The chloroplast genome of C. ficifolium (Genbank accession is MK182725) is 151,823 bp and has four subregions: 83,668 bp of large single copy (LSC) and 17,937 bp of small single copy (SSC) regions are separated by 25,109 bp of inverted repeat (IR) regions. It contains 129 genes (84 protein-coding genes, eight rRNAs, and 37 tRNAs); 19 genes (eight protein-coding genes, four rRNAs, and seven tRNAs) are duplicated in IR regions. The overall GC content of C. ficifolium is 37.3% and those in the LSC, SSC, and IR regions are 35.3%, 31.0%, and 42.7%, respectively.

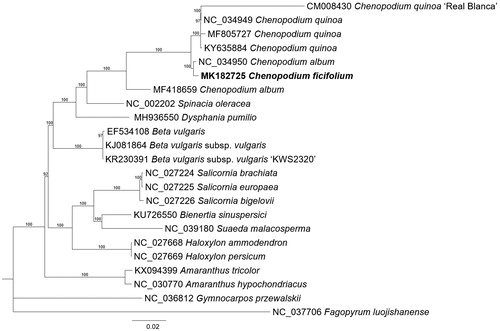

Twenty-one complete chloroplast genomes of Amaranthaceae including seven Chenopodium (Devi and Thongam Citation2017; Hong et al. Citation2017; Wang et al. Citation2017) and one Dysphania (Kim et al., Citation2019) chloroplast genomes were used for constructing phylogenic trees. Whole chloroplast genome sequences were aligned using MAFFT 7.388 (Katoh and Standley Citation2013) for constructing maximum likelihood tree (bootstrap repeat is 1,000) using IQ-TREE (Nguyen et al. Citation2015). Chenopodium album isolated from India Himalayan area (MF418659) of which seed color is white, similar to C. quinoa, makes C. album paraphyletic (Devi and Thongam Citation2017). It indicates that it should be treated as a new species (). In addition, phylogenetic tree shows that C. ficifolium is clustered with C. album forming a monophyletic clade with other Chenopodium species (). The result is consensus with previous studies (Kadereit et al. Citation2003; Fuentes-Bazan, Mansion, et al. Citation2012; Fuentes-Bazan, Uotila, et al. Citation2012). Moreover, C. quinoa ‘Real Blanca’ is quite distinct from other C. quinoa species, which is similar case to C. album (MF418659; ). Our genome will be useful resource to dissect chloroplast genome-based molecular phylogeny of Chenopodium genus.

Figure 1 Maximum likelihood (bootstrap repeat is 1,000) phylogenetic tree of 23 Amaranthaceae complete chloroplast genomes: Chenopodium ficifolium (MK182725, in this study), Chenopodium quinoa ‘Real Blanca’ (CM008430), Chenopodium quinoa (NC_034949, MF805727, and KY635884), Chenopodium album (NC_034950 and MF418659), Spinacia oleracea (NC_002202), Dysphania pumilio (MH936550), Beta vulgaris (EF534108), Beta vulgaris subsp. vulgaris (KJ081864), Beta vulgaris subsp. vulgaris ‘KWS2320’ (KR230391), Salicornia brachiate (NC_027224), Salicornia europaea (NC_027225), Salicornia bigelovii (NC_027226), Bienertia sinuspersici (KU726550), Suaeda malacosperma (NC_039180), Haloxylon ammodendron (NC_027668), Haloxylon persicum (NC_027669), Amaranthus tricolor (KX094399), Amaranthus hypochondriacus (NC_030770), Gymnocarpos przewalskii (NC_036812), Fagopyrum luojishanense (NC_037706). The numbers above branches indicate bootstrap support values of maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Chung Y. 1992. A taxonomic study of the Korean Chenopodiaceae [Ph.D. thesis]. Sungkyunkwan University, Korea (in Korean).

- Devi RJ, Thongam B. 2017. Complete chloroplast genome sequence of Chenopodium album from Northeastern India. Genome Announc. 5:e01150–e01117.

- Fuentes-Bazan S, Mansion G, Borsch T. 2012. Towards a species level tree of the globally diverse genus Chenopodium (Chenopodiaceae). Mol Phylogenet Evol. 62:359–374.

- Fuentes-Bazan S, Uotila P, Borsch T. 2012. A novel phylogeny-based generic classification for Chenopodium sensu lato, and a tribal rearrangement of Chenopodioideae (Chenopodiaceae). Willdenowia. 42:5–24.

- Hong S-Y, Cheon K-S, Yoo K-O, Lee H-O, Cho K-S, Suh J-T, Kim S-J, Nam J-H, Sohn H-B, Kim Y-H. 2017. Complete chloroplast genome sequences and comparative analysis of Chenopodium quinoa and C. album. Front Plant Sci. 8:1696.

- Kadereit G, Borsch T, Weising K, Freitag H. 2003. Phylogeny of Amaranthaceae and Chenopodiaceae and the evolution of C4 photosynthesis. Int J Plant Sci. 164:959–986.

- Katoh K, Standley DM. 2013. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol. 30:772–780.

- Kim Y, Chung Y, Park J. 2019. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Dysphania pumilio (R. Br.) Mosyakin & Clemants (Amaranthaceae). Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 4:403–404.

- Kim C-G, Kil J. 2017. Alien flora of the Korean Peninsula. Seoul (Korea): Nature&Ecology.

- Lee I, Oh Y, Park J, Hong S, Choi J, Heo S, Kim E, Lee C, Park K, Cho S. 2017. Occurrence characteristics of weed flora in Arable Fields of Korea. Weed Turfgrass Sci. 6:86–108.

- Li H. 2013. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. arXiv preprint arXiv:13033997.

- Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, Durbin R. 2009. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 25:2078–2079.

- Nguyen L-T, Schmidt HA, von Haeseler A, Minh BQ. 2015. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol. 32:268–274.

- Park SH. 2009. New illustrations and photographs of naturalized plants of Korea. Ilchokak, Seoul Korea (in Korean).

- Wang K, Li L, Li S, Sun H, Zhao M, Zhang M, Wang Y. 2017. Characterization of the complete chloroplast genome of Chenopodium quinoa Willd. Mitochondr DNA Part B. 2:812–813.

- Zerbino DR, Birney E. 2008. Velvet: algorithms for de novo short read assembly using de Bruijn graphs. Genome Res. 18:821–829.

- Zhao Q-Y, Wang Y, Kong Y-M, Luo D, Li X, Hao P. 2011. Optimizing de novo transcriptome assembly from short-read RNA-Seq data: a comparative study. BMC Bioinform. 12:S2.