Abstract

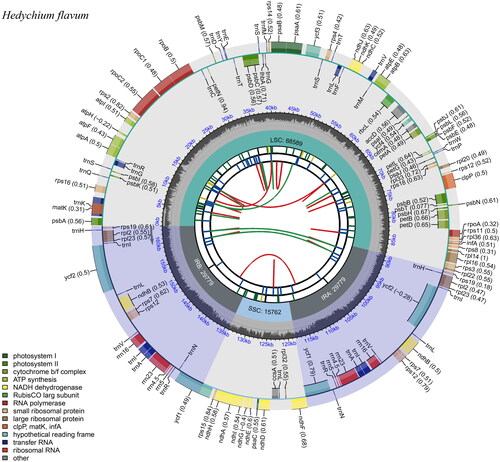

Hedychium flavum Roxb. 1820 is a perennial herb mainly distributed in China, India, Myanmar and Thailand with ornamental, edible and medicinal value. It is extensively cultivated as a source of aromatic essential oils, ornamental plant, food flavorings and vegetables, and folk medicine. In this study, we sequence the complete chloroplast genome of H. flavum by de novo assembly. The assembled genome has a typical quadripartite circular structure with 163,909 bp in length, containing a large single-copy region (LSC, 88,589 bp), a small single-copy region (SSC, 15,762 bp), and two inverted repeat regions (IRs, 29,779 bp). The cp genome contains 133 genes, including 87 protein-coding genes, 38 tRNA genes and 8 rRNA genes. Phylogenetic analysis based on the complete cp genome shows a close affinity of H. flavum and H. neocarneum with 100% bootstrap support. This study will provide useful genetic resource for further phylogenetic analysis of the genus Hedychium and Zingiberaceae.

Introduction

The genus Hedychium (Zingiberaceae), commonly known as ginger lily, comprises approximately 93 species, which are mainly distributed in China, India, and Southeast Asia (Tian et al. Citation2023; The plant list Citation2012). The Hedychium species are herbs with thick, fleshy and aromatic rhizomes and extensively cultivated for their various uses in fragrance, paper, ornamental, cosmetics, medicine, and food industries (Sakhanokho et al. Citation2013; Hartati et al. Citation2014; Tian et al. Citation2020). Hedychium plants are rich in essential oil extracted from leaves, flowers and rhizomes and widely used in high-quality perfumes and traditional medicine for the treatment of asthma, bronchitis, diarrhea, gastric diseases, flu, nausea, snake bites, and leishmaniasis (Basak et al. Citation2010; Hartati et al. Citation2014). Moreover, some species of Hedychium were grown for their edible flowers (He Citation2000).

Hedychium flavum Roxb. 1820 (Roxburgh Citation1820), a perennial tuberous plant, is distributed in China, Thailand, India and Myanmar (Wu and Larsen Citation2000). It is extensively cultivated for its aromatic essential oil or as an ornamental plant. (Wu and Larsen Citation2000; Tian et al. Citation2020). H. flavum has large aromatic flowers forming a terminal spike with an orange spot in the petals () and blooming from August to September (Wu and Larsen Citation2000; Huang et al. Citation2023). Its flowers can remain open for 5-6 days after being cut and placed in bottle, making it an aromatic cut flower with great breeding prospects (Gao et al. Citation2002; Pan and Zhang Citation2013). Furthermore, the rhizomes (commonly known as yehansu) and flowers are widely used in Chinese folk medicine and has remarkable efficacy in treating various diseases, like coughs, stomach pain, bruises, rheumatism and headache (Ai Citation2013; Zhou et al. Citation2018). Meanwhile, their extracted essential oils have a variety of pharmacological effects such as antibacterial, anticancer, insecticidal, anti-inflammatory, and tyrosinase inhibitory properties, with the essential oils of the flowers also being used in cosmetics. (Sakhanokho et al. Citation2013; Tian et al. Citation2020, Citation2023). The rhizomes and young tender shoots of H. flavum are used as vegetables and food flavorings agent (Devi et al. Citation2014).

Figure 1. Species reference image of H. flavum with following distinguished characters: terminal spikes, imbricate bracts, yellow flowers, yellow obcordate labellum with orange at base, and long filament ca. 3 cm. (photo taken by Yong-Hong Zhang in Songming County, yunan province, China).

Previous studies on H. flavum are mainly focused on the utilization as a medicinal, edible, and ornamental plant (Pan and Zhang Citation2013; Tian et al. Citation2020, Citation2023). Until now, no genomic information on H. flavum has been reported. In this study, we sequenced and characterized the complete chloroplast genome of H. flavum to provide useful genetic resource for future molecular study of this species.

Materials and methods

The fresh leaves of H. flavum were collected from a healthy H. flavum individual, growing in Songming County (25°18'27′'N,102°53'14′'E) Yunnan province. The voucher specimens (LMF06) were deposited in the Herbarium of Yunnan Normal University (YNUB, website: https://life.ynnu.edu.cn/, Contact: Jian-Lin Hang, Email: [email protected]).

The total genomic DNA was extracted from fresh leaves using a modified CTAB (cetyl trimethylammonium bromide) method (Allen et al. Citation2006). The constructed library was sequenced using the Illumina Novaseq 6000 platform (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). All raw reads were filtered to obtain clean reads with default parameter using NGS QC Toolkit v2.3.3 (Patel and Jain Citation2012). Based on the clean data, the plastome was de novo assembled using the software NOVOPlasty v4.2 (Dierckxsens et al. Citation2017). Geneious v2022.2.2 (Kearse et al. Citation2012) was used for annotation based on the H. neocarneum (GenBank accession No. MT473709) chloroplast genome (Li et al. Citation2021) and then manually corrected. The annotated chloroplast genome sequence was deposited into GenBank under the accession numbers of OQ308833, and the original reads were also deposited in GenBank. The circular genome map was drawn using CPGView program (Liu et al. Citation2023).

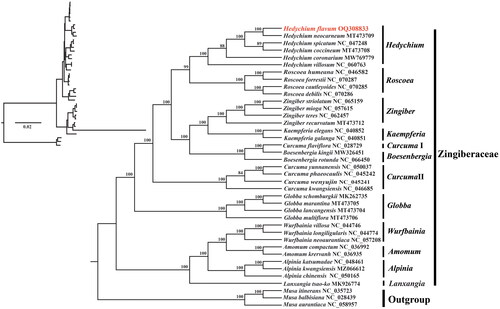

To explore the phylogenetic relationship of H. flavum with its closely related species, a phylogenetic tree was constructed using complete chloroplast genomes of 35 species from Zingiberaceae and three species from Musaceae (as outgroups) downloaded from NCBI GenBank. Total of 39 chloroplast genomes were aligned by the MAFFT v7.490 software (Katoh and Standley Citation2013). Subsequently, nucleotide substitution models were estimated using MEGA 11 (Tamura et al. Citation2021) and the model of GTR + G + I was chosen. The maximum likelihood (ML) tree was reconstructed by using RAxML v8.2.11 (Stamatakis Citation2014). Bootstrap values were calculated from 1,000 replicates to evaluate the reliability of each node.

Results

General feature of the chloroplast genome

The newly assembled plastid genome of H. flavum is 163,909 bp in length. The clean reads (24,029,978) were subjected to assembly to produce a circular molecule of complete chloroplast with about an average 731.4 coverage, which indicated that the genome assembly is reliable (Figure S1). The chloroplast genome of H. flavum had a typical quadripartite structure (). It is divided into four distinct regions: a large single-copy (LSC) region of 88,589 bp, a small single-copy (SSC) region of 15,762 bp, and a pair of inverted repeats (IR) region of 29,779 bp. The GC content in whole cp genome, LSC region, SSC region, and IR regions were 36.1%, 33.9%, 29.6% and 41.1%, respectively.

Figure 2. The chloroplast genome of H. flavum visualized by CPGView. The genome map includes six tracks. From the inward to outward, the first track depicts the dispersed repeats connected by red (forward direction) and green (reverse direction) arcs, respectively. The second track shows the tandem repeats as short blue bars. The third track shows the short tandem repeats or microsatellite sequences as short bars. The small single-copy (SSC), inverted repeat (IRa and IRb), and large single-copy (LSC) regions are shown on the fourth track. The GC content along the genome is plotted on the fifth track. The outermost track shows the genes which are color-coded based on their functional classification. The outer and inner genes are transcribed in the clockwise and counterclockwise directions, respectively. The functional classification of the genes is shown in the left bottom corner.

A total of 133 genes were annotated in the assembled chloroplast genome, including 87 protein-coding genes, 38 transfer RNA genes and eight ribosomal RNA genes. There are 11 cis-splicing genes including rps16, atpF, rpoC1, petB, ycf3, clpP, petD, rpl6, rpl2, ndhB, and ndhA (Figure S2A) and one trans-splicing genes rps12 (Figure S2B). Most of the genes occurred in a single copy, while 20 genes occurred in double copies (rps19, trnH-GUG, rpl2, rpl23, trnL-CAU, ycf2, trnL-CAA, ndhB, rps7, rps12, trnV-GAC, rrn16, trnI-GAU, trnA-UGC, rrn23, rrn4.5, rrn5, trnR-ACG, trnN-GUU, and ycf1). There were 9 genes with one intron (rps16, atpF, rpoC1, petB, petD, rpl6, rpl2, ndhB, and ndhA), and 3 genes with two introns (rps12, ycf3, and clpP).

Phylogenetic analysis of H. flavum in the family Zingiberaceae

Based on the chloroplast genome dataset, we generated a well-supported phylogenetic tree (). The inferred phylogenetic tree indicated that the selected species from the Zingiberaceae were clustered within a lineage distinct from the outgroups. Within Zingiberaceae, the genus Hedychium forms a monophyly, and is closely related to the genus Roscoea. The phylogenetic tree also shows a close affinity of H. flavum and H. neocarneum with 100% bootstrap support.

Figure 3. The maximum likelihood tree of H. flavum and its related relatives based on the complete chloroplast genomes. Bootstrap values were shown next to the nodes. The following sequences were used: Alpinia chinensis NC_050165 (Mei et al. Citation2020), A. katsumadae NC_048461 (Li et al. Citation2020), A. kwangsiensis MZ066612 (Zhang et al. Citation2021), Amomum compactum NC_036992 (Wu et al. Citation2018), A. krervanh NC_036935 (Wu et al. Citation2017), Boesenbergia kingii MW326451 (Liang and Chen Citation2021), B. rotunda NC_066450 (Liew et al. Citation2022), Curcuma flaviflora NC_028729 (Zhang et al. Citation2016), C. kwangsiensis NC_046685 (Gui et al. Citation2020), C. phaeocaulis NC_045242, C. wenyujin NC_045241 (Kim et al. Citation2021), C. yunnanensis NC_050037 (Liang et al. Citation2020), Globba lancangensis MT473704, G. marantina MT473705, G. multiflora MT473706, G. schomburgkii MK262735 (Li et al. Citation2021), H. coccineum MT473708 (Li et al. Citation2021), H. coronarium MW769779 (Yang et al. Citation2021), H. neocarneum MT473709 (Li et al. Citation2021), H. spicatum NC_047248 (Unpublished), H. villosum NC_060763 (Yang et al. Citation2021), Kaempferia elegans NC_040852, K. galanga NC_040851 (Li et al. Citation2019), Lanxangia tsao-ko MK926774 (Ma and Lu Citation2020), Musa aurantiaca NC_058957 (Feng et al. Citation2020), M. balbisiana NC_028439 (Niu et al. Citation2018), M. itinerans NC_035723 (Zhang et al. Citation2019), Roscoea cautleyoides NC_070285 (Unpublished), R. debilis NC_070286 (Unpublished), R. forrestii NC_070287 (Unpublished), R. humeana NC_046582 (Zhu et al. Citation2019), Wurfbainia longiligularis NC_044774 (Cui et al. Citation2019), W. neoaurantiaca NC_057208 (Li et al. Citation2019), W. villosa NC_044746 (Cui et al. Citation2019), Zingiber mioga NC_057615 (Unpublished), Z. recurvatum MT473712 (Li et al. Citation2021), Z. striolatum NC_065159 (Tian et al. Citation2023), Z. teres NC_062457 (Unpublished).

Discussion and conclusion

In the present study, the chloroplast genome of H. flavum was sequenced, assembled, and annotated for the first time. The results showed that the genome size, overall GC content, genome quadripartite structure, and gene composition in the H. flavum chloroplast genome were highly similar to chloroplast genome of other species of Hedychium (Li et al. Citation2019; Yang et al. Citation2021). These results suggested that the chloroplast genomes of Hedychium species were highly conserved at the genus level. The IR regions have a higher GC content (41.1%) than LSC (33.9%) and SSC (29.6%). The higher GC content in the IR region may be due to the presence of rRNA genes, while the SSC region contains most of the NADH genes (Cai et al. Citation2006).

Phylogenetic analysis demonstrated that the genus Hedychium is monophyletic, which is consistent with the results of phylogenetic analysis based on nuclear ITS, chloroplast matK/trnL-trnF sequences, and single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) matrix of chloroplast genome (Wood et al. Citation2000; Ngamriabsakul et al. Citation2004; Li et al. Citation2021). Based on the phylogenetic study of chloroplast genome SNP matrix, there is a close relationship between Hedychium and Globba (Li et al. Citation2021). However, our study showed that Hedychium is closely related to Roscoea, which is inconsistent with the previous findings. Phylogenetic analysis also showed a close affinity of H. flavum and H. neocarneum. However, due to the limited sequence of Hedychium cp genomes, the phylogenetic relationship in the genus requires further study. This study provides the cp genome information of H. flavum, which would contribute to the species identification and phylogenetic analysis within Hedychium and Zingiberaceae.

Author’s contribution statement

Yong-Hong Zhang designed the research and revised the manuscript. Mei-Fei Li analyzed data and prepared a preliminary manuscript. Tao Xiao analyzed data and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Ethic statement

This research does not involve ethical issues. H. flavum does not belong to the China Species Red List. The collection of plant material carried out in accordance with guidelines provided by the authors’ institution (Yunnan Normal University) and national regulations.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (968.1 KB)Supplemental Material

Download JPEG Image (1.4 MB)Supplemental Material

Download JPEG Image (677.7 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in GenBank of NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) with accession number OQ308833. The associated BioProject, SRA, and Bio-Sample numbers are PRJNA941112, SRR23703126, SAMN33590324, respectively. The voucher specimens were deposited in the Herbarium of Yunnan Normal University (YNUB, Website: https://life.ynnu.edu.cn/, Contact: Jian-Lin Hang, Email: [email protected]) with the voucher number: LMF06, which is identified by Dr. Yong- Hong Zhang.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ai TM. 2013. Medicinal flora of China. Vol. 12. Beijing: Peking University Medical Press; p. 381–382.

- Allen GC, Flores-Vergara MA, Krasynanski S, Kumar S, Thompson WF. 2006. A modified protocol for rapid DNA isolation from plant tissues using cetyltrimethylammonium bromide. Nat Protoc. 1(5):2320–2325. doi:10.1038/nprot.2006.384.

- Basak S, Sarma GC, Rangan L. 2010. Ethnomedical uses of Zingiberaceous plants of Northeast India. J Ethnopharmacol. 132(1):286–296. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2010.08.032.

- Cai Z, Penaflor C, Kuehl JV, Leebens-Mack J, Carlson JE, dePamphilis CW, Boore JL, Jansen RK. 2006. Complete plastid genome sequences of Drimys, Liriodendron, and Piper: implications for the phylogenetic relationships of magnoliids. BMC Evol Biol. 6(1):77. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-6-77.

- Cui Y, Chen X, Nie L, Sun W, Hu H, Lin Y, Li H, Zheng X, Song J, Yao H, et al. 2019. Comparison and phylogenetic analysis of chloroplast genomes of three medicinal and edible Amomum species. Int J Mol Sci. 20(16):4040. doi:10.3390/ijms20164040.

- Devi NB, Singh PK, Das AK. 2014. Ethnomedicinal utilization of Zingiberaceae in the valley districts of Manipur. IOSR J Environ Sci, Toxicol Food Technol. 8(2):21–23. doi:10.9790/2402-08242123.

- Dierckxsens N, Mardulyn P, Smits G. 2017. NOVOPlasty: de novo assembly of organelle genomes from whole genome data. Nucleic Acids Res. 45(4):e18. doi:10.1093/nar/gkw955.

- Feng H, Chen Y, Xu X, Luo H, Wu Y, He C. 2020. The complete chloroplast genome of Musa acuminata var. chinensis. Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 5(3):2691–2692. doi:10.1080/23802359.2020.1788462.

- Gao JY, Chen J, Xia YM. 2002. Evaluation on ornamental characteristics and selection for promising species of native Zingiberaceous plants in China. Acta Horticul Sin. 29(2):158–162.

- Gui L, Jiang S, Xie D, Yu L, Huang Y, Zhang Z, Liu Y. 2020. Analysis of complete chloroplast genomes of Curcuma and the contribution to phylogeny and adaptive evolution. Gene. 732:144355. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2020.144355.

- Hartati R, Suganda AG, Fidrianny I. 2014. Botanical, phytochemical and pharmacological properties of Hedychium (Zingiberaceae) - a review. Proc Chem. 13:150–163. doi:10.1016/j.proche.2014.12.020.

- He EY. 2000. Study on Hedychium coronarium Koenig’s edibility and its pharmacological experiments. Lishizhen Med Medica Res. 11(1):1077–1078.

- Huang ZJ, Lin L, Liu N. 2023. Morphological characteristics of Hedychium flavum complex (Zingiberaceae) and definition of their taxons. J Trop Subtropical Bot. 31(1):93–100.

- Katoh K, Standley DM. 2013. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol. 30(4):772–780. doi:10.1093/molbev/mst010.

- Kearse M, Moir R, Wilson A, Stones-Havas S, Cheung M, Sturrock S, Buxton S, Cooper A, Markowitz S, Duran C, et al. 2012. Geneious basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics. 28(12):1647–1649. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/bts199.

- Kim MK, Lee WK, Choi YR, Kim J, Kang L, Kang J. 2021. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of three medicinal species; Curcuma longa, Curcuma wenyujin, and Curcuma phaeocaulis (Zingiberaceae). Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 6(4):1363–1364. doi:10.1080/23802359.2020.1768917.

- Li DM, Li J, Wang DR, Xu YC, Zhu GF. 2021. Molecular evolution of chloroplast genomes in subfamily Zingiberoideae (Zingiberaceae). BMC Plant Biol. 21(1):558. doi:10.1186/s12870-021-03315-9.

- Li DM, Zhao CY, Liu XF. 2019. Complete chloroplast genome sequences of Kaempferia galanga and Kaempferia elegans: molecular structures and comparative analysis. Molecules. 24(3):474. doi:10.3390/molecules24030474.

- Li DM, Zhao CY, Zhu GF, Xu YC. 2019. Complete chloroplast genome sequence of Hedychium coronarium. Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 4(2):2806–2807. doi:10.1080/23802359.2019.1659114.

- Li DM, Zhu GF, Xu YC, Ye YJ, Liu JM. 2020. Complete chloroplast genomes of three medicinal Alpinia species: genome organization, comparative analyses and phylogenetic relationships in family Zingiberaceae. Plants (Basel). 9(2):286. doi:10.3390/plants9020286.

- Li ZJ, Zhang J, Liu YY, Liu XL, Li GD, Qian ZG. 2019. Characterization of the complete chloroplast genome of Amomum longiligulare (Zingiberaceae). Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 4(2):2431–2432. doi:10.1080/23802359.2019.1637295.

- Liang H, Chen J. 2021. Comparison and phylogenetic analyses of nine complete chloroplast genomes of Zingibereae. Forests. 12(6):710. doi:10.3390/f12060710.

- Liang H, Zhang Y, Deng J, Gao G, Ding C, Zhang L, Yang R. 2020. The complete chloroplast genome sequences of 14 Curcuma species: insights into genome evolution and phylogenetic relationships within Zingiberales. Front Genet. 11:802. doi:10.3389/fgene.2020.00802.

- Liew YJM, Chua KO, Yong HS, Song SL, Chan KG. 2022. Complete chloroplast genome of Boesenbergia rotunda and a comparative analysis with members of the family Zingiberaceae. Rev Bras Bot. 45(4):1209–1222. doi:10.1007/s40415-022-00845-w.

- Liu SY, Ni Y, Li JL, Zhang XY, Yang HY, Chen HM, Liu C. 2023. CPGView: a package for visualizing detailed chloroplast genome structures. Mol Ecol Resour. 23(3):694–704. doi:10.1111/1755-0998.13729.

- Ma M, Lu B. 2020. The complete chloroplast genome of Amomum tsao-ko. Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 5(1):848–849. doi:10.1080/23802359.2020.1717382.

- Mei Y, Cai S, Xu S, Gu Y, Zhou F, Wang J. 2020. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of medicinal plant Alpinia chinensis (Retz.) Rosc. Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 5(3):3328–3329. doi:10.1080/23802359.2020.1817805.

- Ngamriabsakul C, Newman MF, Cronk QCB. 2004. The phylogeny of tribe Zingibereae (Zingiberaceae) based on ITS (nrDNA) and trnL-F (cpDNA) sequences. Edinburgh J Bot. 60(3):483–507. doi:10.1017/S0960428603000362.

- Niu YF, Gao CW, Liu J. 2018. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of wild banana, Musa balbisian variety 'Pisang Klutuk Wulung’ (Musaceae). Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 3(1):460–461. doi:10.1080/23802359.2018.1462123.

- Pan XP, Zhang XL. 2013. Rapid Propagation of Hedychium flavum Roxb. J Trop Biol. 4(2):189–193.

- Patel RK, Jain M. 2012. NGS QC toolkit: a toolkit for quality control of next generation sequencing data. PLoS One. 7(2):e30619. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0030619.

- Roxburgh W. 1820. Flora Indica. Vol. 1. Serampore: Mission Press; p. 81.

- Sakhanokho HF, Sampson BJ, Tabanca N, Wedge DE, Demirci B, Baser KHC, Bernier UR, Tsikolia M, Agramonte NM, Becnel JJ, et al. 2013. Chemical composition, antifungal and insecticidal activities of Hedychium essential oils. Molecules. 18(4):4308–4327. doi:10.3390/molecules18044308.

- Stamatakis A. 2014. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 30(9):1312–1313. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033.

- Tamura K, Stecher G, Kumar S. 2021. MEGA11: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 11. Mol Biol Evol. 38(7):3022–3027. doi:10.1093/molbev/msab120.

- The plant list. 2012. Version 1.1. [accessed 2022 20 May]. Available from http://www.theplantlist.org/1.1/browse/ A/Zingiberaceae/Hedychium.

- Tian M, Wu X, Lu T, Zhao X, Wei F, Deng G, Zhou Y. 2020. Phytochemical analysis, antioxidant, antibacterial, cytotoxic, and enzyme inhibitory activities of Hedychium flavum rhizome. Front Pharmacol. 11:572659. doi:10.3389/fphar.2020.572659.

- Tian M, Xie D, Yang Y, Tian Y, Jia X, Wang Q, Deng G, Zhou Y. 2023. Hedychium flavum flower essential oil: chemical composition, anti-inflammatory activities and related mechanisms in vitro and in vivo. J Ethnopharmacol. 301:115846. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2022.115846.

- Tian S, Jiang D, Wan Y, Wang X, Liao Q, Li Q, Li H-L, Liao L. 2023. The complete chloroplast genome of Zingiber striolatum Diels (Zingiberaceae). Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 8(1):48–51. doi:10.1080/23802359.2022.2160218.

- Wood TH, Whitten WM, Williams NH. 2000. Phylogeny of Hedychium and related genera (Zingiberaceae) based on ITS sequence data. Edinburgh J Bot. 57(2):261–270. doi:10.1017/S0960428600000196.

- Wu DL, Larsen K. 2000. Zingiberacea. In: Wu ZY, Raven PH, Hong DY, editors. Flora of China. Vol. 24. Beijing: Science Press and St. Louis: Missouri Botanical Garden Press; p. 372.

- Wu M, Li Q, Hu Z, Li X, Chen S. 2017. The complete Amomum kravanh chloroplast genome sequence and phylogenetic analysis of the commelinids. Molecules. 22(11):1875. doi:10.3390/molecules22111875.

- Wu ML, Li Q, Xu J, Li XW. 2018. Complete chloroplast genome of the medicinal plant Amomum compactum: gene organization, comparative analysis, and phylogenetic relationships within Zingiberales. Chin Med. 13(1):10. doi:10.1186/s13020-018-0164-2.

- Yang Q, Fu GF, Wu ZQ, Li L, Zhao JL, Li QJ. 2021. Chloroplast genome evolution in four montane Zingiberaceae taxa in China. Front Plant Sci. 12:774482. doi:10.3389/fpls.2021.774482.

- Zhang Y, Deng J, Li Y, Gao G, Ding C, Zhang L, Zhou Y, Yang R. 2016. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Curcuma flaviflora (Curcuma). Mitochondrial DNA A DNA Mapp Seq Anal. 27(5):3644–3645. doi:10.3109/19401736.2015.1079836.

- Zhang Y, Song M-F, Li Y, Sun H-F, Tang D-Y, Xu A-S, Yin C-Y, Zhang Z-L, Zhang L-X. 2021. Complete chloroplast genome analysis of two important medicinal Alpinia species: alpinia galanga and Alpinia kwangsiensis. Front Plant Sci. 12:705892. doi:10.3389/fpls.2021.705892.

- Zhang Y-Y, Liu F, Tian N, Che J-R, Sun X-L, Lai Z-X, Cheng C-Z. 2019. Characterization of the complete chloroplast genome of Sanming wild banana (Musa itinerans) and phylogenetic relationships. Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 4(2):2614–2616. doi:10.1080/23802359.2019.1642167.

- Zhou XX, Jiang TB, Su XX, Gao WW. 2018. Microstructure features of rhizome and leaves of Hedychium flavum and Hedychium coronarium. Guizhou Agric Sci. 46(8):105–108.

- Zhu XF, Yu XQ, Zhao JL. 2019. The complete chloroplast sequence of Roscoea humeana (Zingiberaceae): analpine ginger in the Hengduan Mountains, China. Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 4(1):1398–1399. doi:10.1080/23802359.2019.1598795.