Abstract

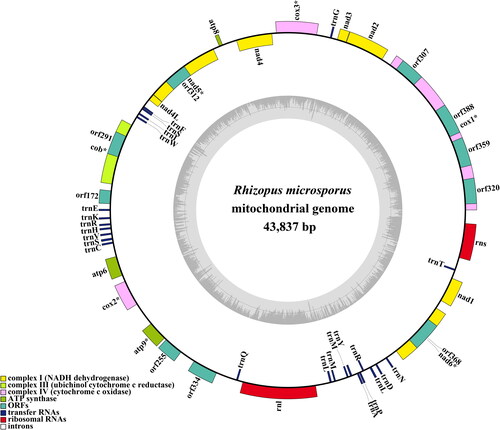

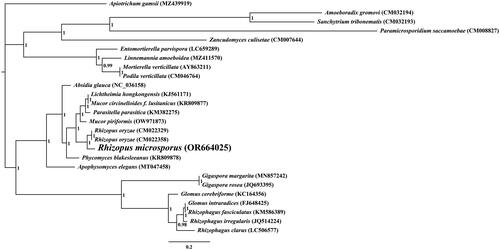

Rhizopus microsporus Tiegh. 1875 is widely used in a variety of industries, such as brewing, wine making, baking, and medicine production, as it has the capability to break down proteins and generate surface-active agents. To date, the mitochondrial genome features of early evolved fungi from the Rhizopus genus have not been extensively studied. Our research obtained a full mitochondrial genome of R. microsporus species, which was 43,837 bp in size and had a GC content of 24.93%. This genome contained 14 core protein-coding genes, 3 independent ORFs, 7 intronic ORFs, 24 tRNAs, and 2 rRNA genes. Through the use of the BI phylogenetic inference method, we were able to create phylogenetic trees for 25 early differentiation fungi which strongly supported the major clades; this indicated that R. microsporus is most closely related to Rhizopus oryzae.

1. Introduction

Rhizopus microsporus Tiegh. 1875 is a soil-borne filamentous fungus with a high ability to degrade protein and produce surface-active agents (Jennessen et al. Citation2005; de Barros Ranke et al. Citation2020). It has been isolated from various habitats including soil, decaying matter, and clinical samples (Yao et al. Citation2021). This species has been found to have a high degree of adaptability and is able to grow under a wide range of environmental conditions (Zhang et al. Citation2015; Yuwa-Amornpitak and Chookietwatana Citation2018). R. microsporus has diverse industrial applications. It is commonly used in brewing, wine making, baking, and medicine production due to its ability to degrade protein and produce surface-active agents (Celestino et al. Citation2006; Martínez-Ruiz et al. Citation2018). Surface-active agents produced by R. microsporus have been found to have biocontrol activities against plant diseases and act as biocides against bacteria and fungi (Orikasa et al. Citation2018; Škríba et al. Citation2020; Xiang et al. Citation2021). These properties make R. microsporus a highly valuable resource for industrial and agricultural applications.

Eukaryotes have a mitochondrial genome, which is indispensable in the regulation of growth and development, sustaining the cell’s homeostasis and enabling it to react to the environment (Ernster and Schatz Citation1981; McBride et al. Citation2006; Murphy Citation2009). It is suggested that the mitochondrial genome is a useful resource for examining fungal phylogeny (Xu and Wang Citation2015; Li, Bao et al. Citation2022, Li, Li et al., Citation2022; Li et al., Citation2023). To date, the mitochondrial genome characteristics of early differentiated fungi from the Rhizopus genus have been not well understood, with only two fungal mitochondrial genomes from the genus reported (Liang et al. Citation2022). In this study, we first obtained the complete mitochondrial genome of R. microsporus, which promotes understanding of the genomic characteristics of early differentiated fungi

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Sample collection

In 2023, a specimen of R. microsporus was isolated from a wine fermentation system in Luzhou (E 105.40°, N 28.91°), Sichuan, China. Morphological and ITS rDNA sequencing were used to identify the specimen, which was then deposited at Culture Collection Center of Chengdu University (contact person: Qiang Li; email: [email protected]) with the voucher number Rmic1 ().

2.2. Mitochondrial genome assembly and annotation

For DNA extraction of R. microsporus, a fungal DNA extraction kit from Omega Bio-Tek (Norcross, GA, USA) was utilized. The NEBNext® Ultra™ II DNA Library Prep Kit (NEB, Beijing, China) was then employed for sequencing library preparation as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Subsequently, the Illumina HiSeq 2500 Platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) was used for whole genome sequencing. To guarantee the accuracy of the data, ngsShoRT (Chen et al. Citation2014) was used to filter out low-quality sequences and AdapterRemoval v2 (Schubert et al. Citation2016) was employed to remove adapter reads. The mitochondrial genome of R. microsporus was de novo assembled using the version 4.3.3 of NOVOPlasty, with a k-mer size of 31 (Dierckxsens et al. Citation2017). The mitochondrial genome was annotated in accordance with our previously described methods (Li et al. Citation2019, Citation2020, Citation2023), which involved the use of the MFannot tool (Valach et al. Citation2014) and MITOS (Bernt et al. Citation2013). By using the NCBI Open Reading Frame Finder, we can forecast or modify PCGs or ORFs that are longer than 100 amino acids (Wu et al. Citation2017). Annotation of the functions of PCGs or ORFs was accomplished through BLASTP searches against the NCBI non-redundant protein sequence database (Bleasby and Wootton Citation1990). Exon and intron boundaries of PCGs were accurately identified with the help of exonerate version 2.2 (Slater and Birney Citation2005). Through the application of tRNAscan-SE v1.3.1, we ascertained and confirmed the presence of tRNA genes in the R. microsporus mitochondrial genome (Lowe and Chan Citation2016). OGDraw v1.2 was employed to generate a graphical representation of the mitochondrial genome (Lohse et al. Citation2013). The structures of intron-containing genes were visualized using the PMGmap online web (http://www.1kmpg.cn/pmgmap) (Zhang et al. Citation2024).

2.3. Phylogenetic analysis

The phylogenetic tree was built using methods that had been described previously (Li et al. Citation2020, Citation2021, Citation2022). Utilizing the MAFFT v7.037 software, we initiated the process by aligning individual mitochondrial genes (excluding intron regions) (Katoh et al. Citation2019). Utilizing SequenceMatrix v1.7.8, we connected the aligned mitochondrial genes to form a single, unified mitochondrial dataset (Vaidya et al. Citation2011). In order to detect any phylogenetic discrepancies between distinct mitochondrial genes, an initial partition homogeneity test was performed using PAUP v 4.0b10 (Swofford Citation2002) according to previous studies (Xiang et al. Citation2013). PartitionFinder 2.1.1 was utilized to pinpoint the most suitable models of partitioning and evolutionary processes for the merged mitochondrial dataset (Lanfear et al. Citation2017). MrBayes v3.2.6 was utilized to construct phylogenetic trees by applying Bayesian inference (Ronquist et al. Citation2012).

3. Results

The average depth of the coverage-depth map was 6398.43× (Supplementary Figure 1), and the mitochondrial genome was 43,837 bp long with a GC content of 24.93%. The structures of genes containing introns were shown in Supplementary Figure 2. The mitochondrial genome of R. microsporus is composed of 37.62% adenine, 13.06% guanine, 37.45% thymine, and 11.87% cytosine. Analysis of the R. microsporus mitochondrial genome revealed 24 open-reading frames, which included 14 core PCGs (cox1, cox2, cox3, atp6, atp8, atp9, cob, nad1, nad2, nad3, nad4, nad4L, nad5, and nad6), 3 free-standing ORFs, and 7 intronic ORFs (). Notably, the proteins encoded by the free-standing ORFs had unknown functions. The R. microsporus mitochondrial genome was found to contain 11 introns, with 8 belonging to Group IB, 3 to Group IA, and 1 to Group I(derived). Intronic ORFs encoding LAGLIDADG homing endonucleases or GIY-YIG homing endonucleases were present in some of the introns. The mitochondrial genome of R. microsporus was found to contain two ribosomal RNA genes, the small subunit (rns) and the large subunit (rnl), as well as 24 transfer RNA genes. Phylogenetic analysis demonstrated that R. microsporus is a sister species to Rhizopus oryzae, as depicted in .

Figure 3. Bayesian inference (BI) tree generated using 14 concatenated mitochondrial protein-coding genes (atp6, atp8, atp9, cob, cox1, cox2, cox3, nad1, nad2, nad3, nad4, nad4L, nad5, and nad6) from rhizopus microspores and 25 other fungal species. Apiotrichum gamsii was set as the outgroup (Li et al. Citation2023). the accession number information of the sequence is as follows: Rhizophagus clarus (LC506577) (Kobayashi et al. Citation2018), Rhizopus microsporus (OR664025), podila verticillata (CM046764) (Morales et al. Citation2022), lichtheimia hongkongensis (KJ561171) (Leung et al. Citation2014), rhizophagus irregularis (JQ514224) (Formey et al. Citation2012), gigaspora rosea (JQ693395) (Nadimi et al. Citation2012), linnemannia amoeboidea (MZ411570) (Yang et al. Citation2022), zancudomyces culisetae (CM007644), Mucor circinelloides f. lusitanicus (KR809877), amoeboradix gromovi (CM032194) (Galindo et al. Citation2021), glomus cerebriforme (KC164356) (Beaudet et al. Citation2013), parasitella parasitica (KM382275) (Ellenberger et al. Citation2014), sanchytrium tribonematis (CM032193) (Galindo et al. Citation2021), mortierella verticillata (AY863211) (Seif et al. Citation2005), entomortierella parvispora (LC659289) (Herlambang et al. Citation2022), absidia glauca (NC_036158) (Ellenberger et al. Citation2016), gigaspora margarita (MN857242) (Venice et al. Citation2020), apophysomyces elegans (MT047458), paramicrosporidium saccamoebae (CM008827) (Quandt et al. Citation2017), mucor piriformis (OW971873) (Papp et al. Citation1999), rhizophagus fasciculatus (KM586389) (Wang et al. Citation2020), phycomyces blakesleeanus (KR809878), rhizopus oryzae (CM022329) (Seif et al. Citation2005), glomus intraradices (FJ648425) (Lee and Young Citation2009), rhizopus oryzae (CM022358) (Nguyen et al. Citation2020), and apiotrichum gamsii (MZ439919) (Li et al. Citation2023).

4. Discussion and conclusion

By utilizing the mitochondrial genome, we can gain a more comprehensive comprehension of the phylogenetic relationship between species (Zhang et al. Citation2020; Ren et al. Citation2021; Zhang et al. Citation2022, Citation2023; Gao et al., Citation2024). The absence of a mitochondrial reference genome for Rhizopodaceae, particularly Rhizopus species, impedes the application of mitochondrial genome for classifying and investigating the phylogenetic relationship of early-diverging fungi (Caramalho et al. Citation2019). In this research, we acquired a full mitochondrial genome of Rhizopus species. It was 43,837 bp in length, with a GC content of 24.93%. This genome included 14 core protein-coding genes (PCGs), 3 independent ORFs, 7 intronic ORFs, 24 tRNAs, and 2 rRNA genes. The R. microsporus mitogenome is the smallest among the three mitogenomes in the Rhizopus genus, 33.94% smaller than R. oryzae and 23.62% smaller than R. arrhizus, respectively, indicating that the R. microsporus mitochondrial genome has undergone contraction during the evolutionary process. By employing the BI phylogenetic inference method, we were able to construct phylogenetic trees for 25 early differentiation fungi, with strong support for major clades; this demonstrated that R. microsporus is most closely related to Rhizopus oryzae. This study provides us with valuable information that is indispensable for the distinction and recognition of Rhizopus species, thus increasing our understanding of mitochondrial evolution and the varieties of early-emerging fungi.

Ethics statement

The study did not involve humans or animals. In this study, samples can be collected without ethical approval or permission.

Authors’ contributions

Y D, Q L and J H planned and designed the research. Y D collected the materials, G-J C performed experiments, Y D and X-D B analyzed the data. Y D and Q L wrote the manuscript.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (316.7 KB)Disclosure statement

All authors have read and approved the final manuscript. No conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

The genome sequence data that support the findings of this study are openly available in GenBank of NCBI at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ under the accession no. OR664025. The associated BioProject, SRA, and Bio-Sample numbers are PRJNA1025866, SRR26320846 and SAMN37723663, respectively.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Beaudet D, Terrat Y, Halary S, de la Providencia IE, Hijri M. 2013. Mitochondrial genome rearrangements in glomus species triggered by homologous recombination between distinct mtDNA haplotypes. Genome Biol Evol. 5(9):1628–1643. doi:10.1093/gbe/evt120.

- Bernt M, Donath A, Jühling F, Externbrink F, Florentz C, Fritzsch G, Pütz J, Middendorf M, Stadler PF. 2013. MITOS: improved de novo metazoan mitochondrial genome annotation. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 69(2):313–319. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2012.08.023.

- Bleasby AJ, Wootton JC. 1990. Construction of validated, non-redundant composite protein sequence databases. Protein Eng. 3:153–159.

- Caramalho R, Madl L, Rosam K, Rambach G, Speth C, Pallua J, Larentis T, Araujo R, Alastruey-Izquierdo A, Lass-Flörl C, et al. 2019. Evaluation of a novel mitochondrial pan-mucorales marker for the detection, identification, quantification, and growth stage determination of mucormycetes. J Fungi (Basel). 5:98.

- Celestino KR, Cunha RB, Felix CR. 2006. Characterization of a beta-glucanase produced by Rhizopus microsporus var. microsporus, and its potential for application in the brewing industry. BMC Biochem. 7(1):23. doi:10.1186/1471-2091-7-23.

- Chen C, Khaleel SS, Huang H, Wu CH. 2014. Software for pre-processing Illumina next-generation sequencing short read sequences. Source Code Biol Med. 9(1):8. doi:10.1186/1751-0473-9-8.

- de Barros Ranke FF, Shinya TY, de Figueiredo FC, Fernández Núñez EG, Cabral H, de Oliva Neto P. 2020. Ethanol from rice byproduct using amylases secreted by Rhizopus microsporus var. oligosporus. Enzyme Partial Purification and Characterization, J Environ Manage. 266:110591.

- Dierckxsens N, Mardulyn P, Smits G. 2017. NOVOPlasty: de novo assembly of organelle genomes from whole genome data. Nucleic Acids Res. 45(4):e18. doi:10.1093/nar/gkw955.

- Ellenberger S, Burmester A, Wöstemeyer J. 2014. Complete mitochondrial DNA sequence of the mucoralean fusion parasite Parasitella parasitica. Genome Announc. 2(6):e00912-14. doi:10.1128/genomeA.00912-14.

- Ellenberger S, Burmester A, Wöstemeyer J. 2016. Complete mitochondrial DNA Sequence of the mucoralean fungus Absidia glauca, a Model for Studying Host-Parasite Interactions. Genome Announc. 4(2):e00153-16. doi:10.1128/genomeA.00153-16.

- Ernster L, Schatz G. 1981. Mitochondria: a historical review. J Cell Biol. 91(3 Pt 2):227s–255s. doi:10.1083/jcb.91.3.227s.

- Formey D, Molès M, Haouy A, Savelli B, Bouchez O, Bécard G, Roux C. 2012. Comparative analysis of mitochondrial genomes of Rhizophagus irregularis – syn. Glomus irregulare – reveals a polymorphism induced by variability generating elements. New Phytol. 196:1217–1227.

- Galindo LJ, López-García P, Torruella G, Karpov S, Moreira D. 2021. Phylogenomics of a new fungal phylum reveals multiple waves of reductive evolution across holomycota. Nat Commun. 12(1):4973. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-25308-w.

- Gao W, Chen X, He J, Sha A, Luo Y, Xiao W, Xiong Z, Li Q. 2024. Intraspecific and interspecific variations in the synonymous codon usage in mitochondrial genomes of 8 pleurotus strains. BMC Genomics. 25(1):456.

- Herlambang A, Guo Y, Takashima Y, Narisawa K, Ohta H, Nishizawa T. 2022. Whole-genome sequence of entomortierella parvispora E1425, a mucoromycotan fungus associated with burkholderiaceae-related endosymbiotic bacteria. Microbiol Resour Announc. 11(1):e0110121. doi:10.1128/mra.01101-21.

- Jennessen J, Nielsen KF, Houbraken J, Lyhne EK, Schnürer J, Frisvad JC, Samson RA. 2005. Secondary metabolite and mycotoxin production by the Rhizopus microsporus group. J Agric Food Chem. 53:1833–1840.

- Katoh K, Rozewicki J, Yamada KD. 2019. MAFFT online service: multiple sequence alignment, interactive sequence choice and visualization. Brief Bioinform. 20(4):1160–1166. doi:10.1093/bib/bbx108.

- Kobayashi Y, Maeda T, Yamaguchi K, Kameoka H, Tanaka S, Ezawa T, Shigenobu S, Kawaguchi M. 2018. The genome of Rhizophagus clarus HR1 reveals a common genetic basis for auxotrophy among arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. BMC Genomics. 19(1):465. doi:10.1186/s12864-018-4853-0.

- Lanfear R, Frandsen PB, Wright AM, Senfeld T, Calcott B. 2017. PartitionFinder 2: new methods for selecting partitioned models of evolution for molecular and morphological phylogenetic analyses. Mol Biol Evol. 34(3):772–773. doi:10.1093/molbev/msw260.

- Lee J, Young JPW. 2009. The mitochondrial genome sequence of the arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus glomus intraradices isolate 494 and implications for the phylogenetic placement of glomus. New Phytol. 183:200–211.

- Leung SY, Huang Y, Lau SK, Woo PC. 2014. Complete mitochondrial genome sequence of Lichtheimia ramosa (syn. Lichtheimia hongkongensis). Genome Announc. 2(4):e00644-14. doi:10.1128/genomeA.00644-14.

- Liang G, Zhang M, Xu W, Wang X, Zheng H, Mei H, Liu W. 2022. Characterization of mitogenomes from four Mucorales species and insights into pathogenicity. Mycoses. 65(1):45–56. doi:10.1111/myc.13374.

- Li Q, Bao Z, Tang K, Feng H, Tu W, Li L, Han Y, Cao M, Zhao C. 2022. First two mitochondrial genomes for the order Filobasidiales reveal novel gene rearrangements and intron dynamics of Tremellomycetes. IMA Fungus. 13(1):7. doi:10.1186/s43008-022-00094-2.

- Li Q, He X, Ren Y, Xiong C, Jin X, Peng L, Huang W. 2020. Comparative mitogenome analysis reveals mitochondrial genome differentiation in ectomycorrhizal and asymbiotic amanita species. Front Microbiol. 11:1382. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2020.01382.

- Li Q, Li L, Zhang T, Xiang P, Wu Q, Tu W, Bao Z, Zou L, Chen C. 2022. The first two mitochondrial genomes for the genus Ramaria reveal mitochondrial genome evolution of Ramaria and phylogeny of basidiomycota. IMA Fungus. 13(1):16. doi:10.1186/s43008-022-00100-7.

- Li Q, Luo Y, Sha A, Xiao W, Xiong Z, Chen X, He J, Peng L, Zou L. 2023. Analysis of synonymous codon usage patterns in mitochondrial genomes of nine amanita species. Front Microbiol. 14:1134228. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2023.1134228.

- Li Q, Ren Y, Shi X, Peng L, Zhao J, Song Y, Zhao G. 2019. Comparative mitochondrial genome analysis of two ectomycorrhizal fungi (rhizopogon) reveals dynamic changes of intron and phylogenetic relationships of the subphylum agaricomycotina. Int J Mol Sci. 20(20):5167. doi:10.3390/ijms20205167.

- Li Q, Ren Y, Xiang D, Shi X, Zhao J, Peng L, Zhao G. 2020. Comparative mitogenome analysis of two ectomycorrhizal fungi (paxillus) reveals gene rearrangement, intron dynamics, and phylogeny of basidiomycetes. IMA Fungus. 11(1):12. doi:10.1186/s43008-020-00038-8.

- Li Q, Wu P, Li L, Feng H, Tu W, Bao Z, Xiong C, Gui M, Huang W. 2021. The first eleven mitochondrial genomes from the ectomycorrhizal fungal genus (boletus) reveal intron loss and gene rearrangement. Int J Biol Macromol. 172:560–572.

- Li Q, Xiao W, Wu P, Zhang T, Xiang P, Wu Q, Zou L, Gui M. 2023. The first two mitochondrial genomes from Apiotrichum reveal mitochondrial evolution and different taxonomic assignment of trichosporonales. IMA Fungus. 14(1):7. doi:10.1186/s43008-023-00112-x.

- Li Q, Zhang T, Li L, Bao Z, Tu W, Xiang P, Wu Q, Li P, Cao M, Huang W. 2022. Comparative mitogenomic analysis reveals intraspecific, interspecific variations and genetic diversity of medical fungus ganoderma. J Fungi (Basel). 8:781.

- Lohse M, Drechsel O, Kahlau S, Bock R. 2013. OrganellarGenomeDRAW – a suite of tools for generating physical maps of plastid and mitochondrial genomes and visualizing expression data sets. Nucleic Acids Res. 41(Web Server issue):W575–581. doi:10.1093/nar/gkt289.

- Lowe TM, Chan PP. 2016. tRNAscan-SE On-line: integrating search and context for analysis of transfer RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 44(W1):W54–57. doi:10.1093/nar/gkw413.

- Martínez-Ruiz A, Tovar-Castro L, García HS, Saucedo-Castañeda G, Favela-Torres E. 2018. Continuous ethyl oleate synthesis by lipases produced by solid-state fermentation by Rhizopus microsporus. Bioresour Technol. 265:52–58.

- McBride HM, Neuspiel M, Wasiak S. 2006. Mitochondria: more than just a powerhouse. Curr Biol. 16(14):R551–560. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2006.06.054.

- Morales DP, Robinson AJ, Pawlowski AC, Ark C, Kelliher JM, Junier P, Werner JH, Chain PSG. 2022. Advances and challenges in fluorescence in situ hybridization for visualizing fungal endobacteria. Front Microbiol. 13:892227. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2022.892227.

- Murphy MP. 2009. How mitochondria produce reactive oxygen species. Biochem J. 417(1):1–13. doi:10.1042/BJ20081386.

- Nadimi M, Beaudet D, Forget L, Hijri M, Lang BF. 2012. Group I intron-mediated trans-splicing in mitochondria of Gigaspora rosea and a robust phylogenetic affiliation of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi with mortierellales. Mol Biol Evol. 29(9):2199–2210. doi:10.1093/molbev/mss088.

- Nguyen MH, Kaul D, Muto C, Cheng SJ, Richter RA, Bruno VM, Liu G, Beyhan S, Sundermann AJ, Mounaud S, et al. 2020. Genetic diversity of clinical and environmental mucorales isolates obtained from an investigation of mucormycosis cases among solid organ transplant recipients. Microb Genom. 6:mgen000473.

- Orikasa Y, Oda Y, Ohwada T. 2018. Identification of sucA, Encoding β-Fructofuranosidase, in Rhizopus microsporus. Microorganisms. 6(1):26. doi:10.3390/microorganisms6010026.

- Papp T, Palágyi Z, Ferenczy L, Vágvölgyi C. 1999. The mitochondrial genome of Mucor piriformis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 171(1):67–72. doi:10.1016/S0378-1097(98)00581-3.

- Quandt CA, Beaudet D, Corsaro D, Walochnik J, Michel R, Corradi N, James TY. 2017. The genome of an intranuclear parasite, Paramicrosporidium saccamoebae, reveals alternative adaptations to obligate intracellular parasitism. Elife. 6:e29594. doi:10.7554/eLife.29594.

- Ren LY, Zhang S, Zhang YJ. 2021. Comparative mitogenomics of fungal species in stachybotryaceae provides evolutionary insights into hypocreales. Int J Mol Sci. 22:13341.

- Ronquist F, Teslenko M, van der Mark P, Ayres DL, Darling A, Höhna S, Larget B, Liu L, Suchard MA, Huelsenbeck JP. 2012. MrBayes 3.2: efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst Biol. 61(3):539–542. doi:10.1093/sysbio/sys029.

- Schubert M, Lindgreen S, Orlando L. 2016. AdapterRemoval v2: rapid adapter trimming, identification, and read merging. BMC Res Notes. 9(1):88. doi:10.1186/s13104-016-1900-2.

- Seif E, Leigh J, Liu Y, Roewer I, Forget L, Lang BF. 2005. Comparative mitochondrial genomics in zygomycetes: bacteria-like RNase P RNAs, mobile elements and a close source of the group I intron invasion in angiosperms. Nucleic Acids Res. 33:734–744.

- Škríba A, Patil RH, Hubáček P, Dobiáš R, Palyzová A, Marešová H, Pluháček T, Havlíček V. 2020. Rhizoferrin glycosylation in Rhizopus microsporus. J Fungi (Basel). 6:89.

- Slater GS, Birney E. 2005. Automated generation of heuristics for biological sequence comparison. BMC Bioinformatics. 6(1):31. doi:10.1186/1471-2105-6-31.

- Swofford D. 2002. PAUP*. Phylogenetic analysis using parsimony (*and other methods). version 4.0b10. 4 ed.

- Vaidya G, Lohman DL, Meier R. 2011. SequenceMatrix: concatenation software for the fast assembly of multi‐gene datasets with character set and codon information. Cladistics. 27(2):171–180. doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.2010.00329.x.

- Valach M, Burger G, Gray MW, Lang BF. 2014. Widespread occurrence of organelle genome-encoded 5S rRNAs including permuted molecules. Nucleic Acids Res. 42(22):13764–13777. doi:10.1093/nar/gku1266.

- Venice F, Ghignone S, Salvioli di Fossalunga A, Amselem J, Novero M, Xianan X, Sędzielewska Toro K, Morin E, Lipzen A, Grigoriev IV, et al. 2020. At the nexus of three kingdoms: the genome of the mycorrhizal fungus Gigaspora margarita provides insights into plant, endobacterial and fungal interactions. Environ Microbiol. 22:122–141.

- Wang X, Wang M, Liu X, Tan A, Liu N. 2020. Mitochondrial genome characterization and phylogenetic analysis of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus Rhizophagus sp. Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 5:810–811.

- Wu L, Sun Q, Desmeth P, Sugawara H, Xu Z, McCluskey K, Smith D, Alexander V, Lima N, Ohkuma M, et al. 2017. Database resources of the national center for biotechnology information. Nucleic Acids Res. 45(D1):D611–D618.

- Xiang XG, Schuiteman A, Li DZ, Huang WC, Chung SW, Li JW, Zhou HL, Jin WT, Lai YJ, Li ZY, et al. 2013. Molecular systematics of dendrobium (orchidaceae, dendrobieae) from mainland Asia based on plastid and nuclear sequences. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 69:950–960.

- Xiang M, Wang L, Yan Q, Jiang Z, Yang S. 2021. Heterologous expression and biochemical characterization of a cold-active lipase from Rhizopus microsporus suitable for oleate synthesis and bread making. Biotechnol Lett. 43(9):1921–1932. doi:10.1007/s10529-021-03167-1.

- Xu JP, Wang PF. 2015. Mitochondrial inheritance in basidiomycete fungi. Fungal Biol Rev. 29:209–219.

- Yang Y, Liu XY, Huang B. 2022. The complete mitochondrial genome of linnemannia amoeboidea (W. Gams) vandepol & bonito (mortierellales: mortierellaceae). Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 7:374–376.

- Yao D, Xu L, Wu M, Wang X, Wang K, Li Z, Zhang D. 2021. Microbial community succession and metabolite changes during fermentation of BS sufu, the fermented black soybean curd by rhizopus microsporus, rhizopus oryzae, and actinomucor elegans. Front Microbiol. 12:665826. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2021.665826.

- Yuwa-Amornpitak T, Chookietwatana K. 2018. Bioconversion of waste cooking oil glycerol from cabbage extract to lactic acid by Rhizopus microsporus. Braz J Microbiol. 49(1):178–184.

- Zhang X, Chen H, Ni Y, Wu B, Li J, Burzyński A, Liu C. 2024. Plant mitochondrial genome map (PMGmap): A software tool for the comprehensive visualization of coding, noncoding and genome features of plant mitochondrial genomes. Mol Ecol Resour. e13952.

- Zhang YJ, Fan XP, Li JN, Zhang S. 2023. Mitochondrial genome of cordyceps blackwelliae: organization, transcription, and evolutionary insights into cordyceps. IMA Fungus. 14(1):13. doi:10.1186/s43008-023-00118-5.

- Zhang S, Wang S, Fang Z, Lang BF, Zhang YJ. 2022. Characterization of the mitogenome of Gongronella sp. w5 reveals substantial variation in mucoromycota. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 106(7):2587–2601. doi:10.1007/s00253-022-11880-8.

- Zhang S, Wang Y, Zhang N, Sun Z, Shi Y, Cao X, Wang H. 2015. Purification and characterisation of a fibrinolytic enzyme from Rhizopus microsporus var. tuberosus. Food Technol Biotechnol. 53(2):243–248. doi:10.17113/ftb.53.02.15.3874.

- Zhang Y, Yang G, Fang M, Deng C, Zhang KQ, Yu Z, Xu J. 2020. Comparative analyses of mitochondrial genomes provide evolutionary insights into nematode-trapping fungi. Front Microbiol. 11:617. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2020.00617.