ABSTRACT

This article critically examines long-term media effects in communication research. Focusing on news exposure, the purpose is to provide a review and theoretical conceptualization of long-term effects on societal beliefs. The first part presents an empirical overview of research published in leading communication journals. While longitudinal studies are not uncommon, few have an explicit and elaborated focus on long-term influences. To advance future research, the second part builds on cognitive schema theory to develop three distinct ways of conceptualizing long-term effects: in terms of (a) effect duration, (b) effect mechanisms and (c) effect dynamics. Finally, the third part condenses a comprehensive literature review into a multilevel framework model of factors contributing to long-term media effects on societal beliefs.

Public opinion rests on citizens’ perceptions of societal problems. How such perceptions are shaped is, therefore, fundamental for democracy and political accountability (Kinder & Kiewiet, Citation1981; Mutz, Citation1998). In a classic 100 year-old quote, Lippmann succinctly captured the problem facing every citizen in democratic societies: ‘[t]he world that we have to deal with politically, is out of reach, out of sight, and out of mind’ (Citation1922/1997, p. 18). Lippmann wrote in the very early days of the modern mass media era, but his ideas on how the press shapes perceptions of the world outside have inspired an entire field of political and mass communication research. Today's discussions concerning misperceptions, polarization, ‘fake news’ and social media underscore a consistent interest in the relationship between media environments and worldviews among citizens.

Despite the accumulation of evidence for various media effects on public opinion, a question critical to the entire field remains unsettled: Under what conditions are media effects consequential and long-lasting, as opposed to transient and short-lived? This question reflects a mismatch between media effects theory and research designs employed in the field, a disconnection typically noted in reviews of classic effect theories. For instance, Tewksbury and Scheufele (Citation2009) note that ‘[f]raming effects are, almost exclusively, conceptualized as long-term in nature’ and that most ‘political communication researchers […] are interested in the impact of exposure to messages on enduring beliefs and opinions about an issue’ (p. 29). Still, the typical framing effects study is a one-shot experiment. Another example comes from cultivation research, which explicitly theorizes long-term influences on citizens’ beliefs about society. A review of almost 40 years of cultivation research concluded that ‘the literature has moved toward a pattern of research practices that test short-term reactions to specific message elements’ and therefore ‘[m]uch of what is labeled as cultivation research now is oriented toward testing claims made by many other media effects theories much more than the claims made by cultivation theory’ (Potter, Citation2014, p. 1032). Similarly, Perse and Lambe (Citation2017) note that ‘much research has been limited to short-term manifestations of ‘effects’ that can be easily measured in laboratories or in surveys’, leading them to conclude that, ‘ … for the most part, research has not considered the effects of long-term, cumulative media exposure’ (p. 15).

As these examples illustrate, classic theories of media effects emphasize the importance of long-term influences of the media. Empirical studies, however, seldom reflect such conceptualizations or assumptions. In this article, we examine long-term media effects in communication research, focusing on the effects of news exposure. More specifically, our purpose is to provide a comprehensive review and theoretical conceptualization of long-term media effects on societal beliefs.

To accomplish this goal, the article is organized into three main sections. First, we present an overview of empirical research in leading communication science journals. Focusing on agenda-setting, cultivation and framing effects, this overview illustrates that most studies do not deal specifically with long-term effects – and when they do, the approach to long-term effects is rather narrow. Second, we build on cognitive schema theory to develop a more comprehensive conceptualization of long-term media effects. Apart from the more typical (1) effect duration approach, this section suggests (2) specific mechanisms and (3) a typology of effect dynamics as alternative ways of understanding long-term media effects. Based on this more elaborated conceptualization of long-term effects, the third part of the paper condenses our literature review into a multilevel framework of factors contributing to long-term media effects. A conditional effects model integrating news content, recipient and context characteristics is proposed to explain belief formation in an increasingly fragmented media environment. We end the paper with a call for more integrative approaches to the study of long-term media effects as well as suggestions for future research avenues.

An overview of long-term media effects in published work

To inform our discussion about long-term media effects, we start by looking into empirical research on three key theories in the field: agenda-setting, cultivation and framing. Agenda-setting theorizes the transfer of salience of objects (first-level) and attributes (second-level) from the media agenda to the public agenda, relying on accessibility effects as the primary mechanism (McCombs, Citation2014; Scheufele, Citation2000). Cultivation theory focuses on how exposure to television influences societal perceptions in line with the television portrayals, typically related to beliefs about the prevalence of crime (Morgan & Shanahan, Citation2010). Finally, the accessibility, applicability and activation of cognitive schemas play a key role in psychological models of framing effects (Chong & Druckman, Citation2007; Price & Tewksbury, Citation1997; Scheufele, Citation2004).

Our overview focuses on research published in five top communication journals: Communication Research, Journal of Communication, Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, Political Communication and Public Opinion Quarterly. Using the bibliometric research software ‘Harzing–publish or perish’, we collected the articles that contained the name of each theory (i.e. agenda-setting, cultivation and framing), published between 1972 and 2019. A second search in all abstracts was then conducted to uncover articles that use agenda-setting, cultivation or framing as central concepts, resulting in approximately 2,300 articles in total. We finally selected only those articles that focused on media effects on public opinion – excluding those focusing on elites, political actors or media content only. The final sample consists of 131 articles (agenda-setting=61, cultivation=31 and framing=39).Footnote1 While this sample of journal articles cannot offer a complete picture of the huge amount of research into these media effect theories, the collection represents important and influential studies that illustrate main tendencies and biases from a long-term media effects perspective. We were particularly interested in the extent to which long-term effects are the main focus in these studies and what research designs are used to capture these media effects – as well as how this differs across the three theories. Two main findings emerged from this exploration.

Main focus: Though assumptions about long-term dynamics often remain implicit in studies of agenda-setting, cultivation and framing, few empirical studies deal explicitly with long-term effects as a main research question (15%). Two types of studies can be identified in this regard. First, a number of framing effect studies address matters such as effect duration and longevity (e.g. Lecheler & de Vreese, Citation2011, Citation2013; Rhee, Citation1997; Tewksbury et al., Citation2000). By including delayed post-test measurements – sometimes with additional in-between treatments – these studies analyze how long framing effects last. Second, a few agenda-setting studies deal with similar issues related to optimal cause–effect time lags. Combining media content and longitudinal survey data, these studies seek to determine the time frame during which agenda-setting operates (e.g. Neuman, Citation1990; Watt et al., Citation1993; Zhu et al., Citation1993).

Research design: While few studies have an explicit focus on addressing long-term effects, their overall research designs may be more or less suitable for analyzing such dynamics empirically. The research designs employed differ substantially across the three theories, which has significant implications for the ability to capture long-term influences. Longitudinal approaches are, for instance, most common in studies on agenda-setting (53%), followed by studies on framing (33%) and cultivation (13%) effects. The longitudinal designs of agenda-setting and framing studies are very different, however. While the typical longitudinal framing effects study employs an experimental pretest-posttest design, with a relatively short time-lag (days or weeks), longitudinal agenda-setting studies tend to focus on more long-term processes (monthly or quarterly measurements). Another important methodological difference is that nine out of ten agenda-setting (89%) and cultivation (90%) studies are based on observational data, while framing effects research is heavily dominated by experimental designs (87%).

In short, despite the emphasis on long-term influences in media effects theory, our empirical overview indicates that very few studies actually deal explicitly with long-term effect dynamics. Instead, they focus on other research questions. Most research addresses particular relationships and hypotheses derived from the specific theories – such as the relationship between the media agenda and public agenda (agenda-setting), television viewing and crime perceptions (cultivation) or media frames and policy attitudes (framing) – without paying specific attention to time-related aspects per se.

Most importantly, the few studies that do have some sort of long-term effects focus, rely on a rather narrow understanding of long-term as a matter of optimal time lags and effect duration. As we outline in the next section, this approach represents only one way of theoretically conceptualizing ‘long-term’ media effects. In the remainder of this article, we therefore seek to advance a more comprehensive approach to the study of long-term influences, anchored in theories of cognitive schemas.

Schema theory and three conceptualizations of long-term effects

Our proposed conceptualization of long-term media effects builds on theories of mental models and cognitive schemas. This approach has important advantages. First, a schema perspective is broadly applicable to a wide range of cognitive media effect theories, including agenda-setting, cultivation and framing (Chong & Druckman, Citation2007; Fiske & Taylor, Citation2017; McCombs, Citation2014). Second, schema theory provides a theoretical basis for elaborating on conceptual aspects of long-term influences on societal beliefs.

Beliefs about society are anchored in cognitive schemas – the mental representations that structure perceptions of issues, events and actors. To simplify and comprehend the complex and chaotic world outside, people organize their cognitive representations of various societal problems as mental models, consisting of objects, attributes and relations between these attributes (Fiske & Taylor, Citation2017). Hence, societal beliefs can be specified as ‘associations people create between an object and its attributes’ regarding societal matters (Cottam et al., Citation2016, p. 48; see also Eagly & Chaiken, Citation1998; Potter, Citation2012). In addition to structuring knowledge, schemas (1) guide selective exposure, attention and perception, (2) facilitate interpretation of incoming information and (3) reduce uncertainty and allow inferences in new situations. Schemas, thus, help filling in the blanks when information is missing (Matthes, Citation2008; Perse & Lambe, Citation2017).

Cognitive schemas are hierarchically structured with higher-order (abstract) representations subsuming lower-order (specific) representations of issues, events and actors. These mental representations are typically highly stable and resistant. Under specific circumstances, however, they are also dynamic and open for change (Fiske & Taylor, Citation2017; Roskos-Ewoldsen et al., Citation2009). People’s tendency to strive for belief consistency means that schemas are preserved and maintained through assimilation as incongruent information is adapted to fit preexisting schemas. Through accommodation, in contrast, schemas are updated and revised in response to new information. Schema change involves a variety of accommodations, such as (1) establishing new object attributes; (2) strengthening or weakening of already existing object-attribute and attribute-attribute relations; (3) replacing schema relevant cases as specific representations of objects; or (4) increasing schema complexity and differentiation as domain-specific knowledge and expertise grow (Crocker et al., Citation1984; Scheufele, Citation2004). We regard all such forms of schema change as accommodation. This means that accommodation of schemas can generate a variety of belief dynamics involving the formation, stability and change of specific beliefs – a topic elaborated upon below.

Schema theory allows us to clarify and develop our understanding of long-term media effects on societal beliefs. Distinctions between short-term and long-term effects can be clarified by considering issues relating to the activation of preexisting schemas, the characteristics of schemas, as well as the processes through which schemas accommodate. Accordingly, we outline three ways of conceptualizing long-term media effects: in terms of (1) effect duration, (2) effect mechanisms and (3) effect dynamics. These conceptualizations emphasize specific theoretical issues with implications for research design and measurements, but are not mutually exclusive. In particular, the conceptualizations provide three answers to the basic question: what is a long-term media effect?

Answer 1: long-term as a matter of effect duration

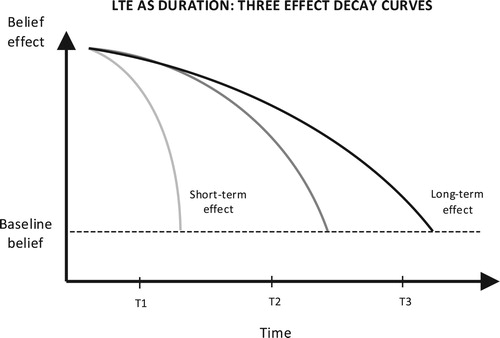

The first way of thinking about long-term effects was most prominent in our overview of studies on agenda-setting, cultivation and framing – defining long-term from an empirical perspective. Long-term effects are those that survive some empirically defined time threshold, usually decided by the research design employed. illustrates the basic idea behind long-term effects as a matter of effect duration.

A typical short-term effect is the immediate activation of a preexisting schema following exposure to certain content. The activation level may follow various decay curves as illustrated in , but schema activation entails no change of the schemas as such. Exposure to an issue-specific news frame on immigration may, for instance, activate one of several preexisting cognitive schemas, which, in turn, influences issue interpretations and overall assessments on whether immigration has a positive or negative impact on society (Chong & Druckman, Citation2007; Matthes & Schemer, Citation2012). A long(er)-term effect displays a less steep decay curve (Chong & Druckman, Citation2010; Koch & Arendt, Citation2017). Thus, long-term is simply defined in relative terms in contrast to short-term effects, which are those that fade more quickly after exposure. Importantly, while illustrates a very specific curve, the shape and rate of decay may vary significantly between media effects and outcomes. The main conceptual distinction between short- and long-term effects is still the same, however.

This way of addressing questions about the longevity of media effects is typical for agenda-setting studies employing time-series analysis, as well as a number of framing experiments looking at effect duration. Duration is often assumed to depend on the strength of the initial effect, with the rate of decay reliant upon some moderator variable at the content, individual or contextual level (see framework model in part 3 below). Since duration primarily relies on schema activation as a source of influence – rather than accommodation of schemas – this approach reflects a rather narrow understanding of long-term effects.

Answer 2: long-term as a matter of effect mechanisms

A second conceptualization builds on specific properties of cognitive schemas. Two schema dimensions are important for understanding short and long-term media effects on societal beliefs: (1) level of schema development and (2) level of schema abstraction.

On the one hand, people differ in how well developed their schemas for particular domains and topics are. Experience, knowledge and expertise influence the amount of stored information, and how well organized, connected and integrated such information is (Cappella & Jamieson, Citation1997; Fiske & Taylor, Citation2017). Both between-person and between-domain differences are relevant here. A person may be an expert with highly developed schemas in one area, but completely ignorant (aschematic) on another (Crocker et al., Citation1984).

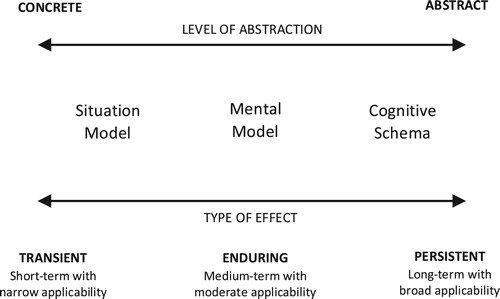

On the other hand, level of abstraction also matters. As noted above, schemas are hierarchically ordered, with higher- and lower-ordered objects and attributes structured vertically – as well as subcategories at each vertical level organized horizontally. Individual schemas are also embedded in a network of relationships, ranging from the more concrete and specific representations to higher levels of abstraction (Cappella & Jamieson, Citation1997; Conover & Feldman, Citation1984). The distinction between situation models, mental models and schemas is particularly fruitful here, since ‘there is a continuum of abstractness along which mental representations exist, from a situation model (least abstract) to a mental model to a schema (most abstract)’ (Roskos-Ewoldsen et al., Citation2009, p. 85). While situation models contain representations of specific stories, actors and events, schemas are more generic.

Situation models and schemas also vary in their degree of contextualization and mutability. Situation models of specific actors and events are constructed immediately, ‘on the fly’, as people consume news stories. These traces of influence may – or may not – have subsequent impact on higher-order mental representations. Thus, the more specific the mental representation, the greater the potential (short-term) impact of communication (Roskos-Ewoldsen et al., Citation2004; see also Scheufele, Citation2004; Wyer & Radvansky, Citation1999). In contrast, since higher-order schemas are more durable and generic than their lower-order counterparts, their applicability to various judgmental tasks also extend beyond specific situations in both time and space. While situation models of specific events or stories more quickly lose their impact, mental models and schemas can be activated for a longer period of time (Roskos-Ewoldsen et al., Citation2009).

Inspired by Mitchell (Citation2012), summarizes the implications of these schema characteristics. More than simply a matter of effect duration, long-term should be defined in terms of the type of effect media have on societal beliefs – or the psychological mechanisms that link lower-order situation models to accommodation of higher-order schemas. In most cases, media effects are highly transient and limited, momentarily affecting perceptions of specific narratives, events and characters during exposure (situation models). A news story about a specific crime will create immediate perceptions of the particular story, for example, how exactly the pickpocket stole the victim’s handbag. This concrete sequence of events will, however, fade quickly from memory after exposure.

At other times, effects are more enduring, extending beyond the immediate situation by influencing perceptions of somewhat broader sets of events or themes (mental models). Persistent effects are those that also involve schema accommodation, targeting perceptions of broader classes of events, actors and structures. Now more generic perceptions of crime, which go beyond the specific pickpocketing story, are affected. These could include perceptions of the state of affairs in the local community or crime developments in the country, the larger causes and consequences of crime, or even more abstract beliefs about the trustworthiness of people in general. Effects are long-term in the sense that accommodated schemas are broadly applicable to various situations and highly stable over time. Thus, abstract schemas are less likely to change than situation models in response to news coverage, but their long-term impact is far greater. Long-term media effects depend on whether the initial formation and subsequent updating of situation models in response to media stimuli translate into accommodation of higher-order schemas that persist over time – schemas that can later be applied frequently and widely in a variety of settings.

Answer 3: long-term as a matter of effect dynamics

A third way of conceptualizing long-term effects focuses on distinct effect dynamics that manifest only over time. Changes at more specific levels of a schema do not always influence abstract levels. Schema theory suggests three models of such change (Balogun & Johnson, Citation2004; Crocker et al., Citation1984). First, according to the bookkeeping model, schema adjustments occur incrementally in response to belief-inconsistent information. Second, the conversion model describes fundamental ‘all-or-none’ shifts, in the sense that ‘schemata can change massively and suddenly in response to dramatic or salient instances that deviate from prior experiences’ (Balogun & Johnson, Citation2004, p. 525). Third, the subtyping model outlines change as a form of differentiation affecting the structure of schemas. When incongruent information cannot be assimilated into a preexisting schema, subcategories are created at more specific levels of the schema (Crocker et al., Citation1984; Fiske & Taylor, Citation2017).

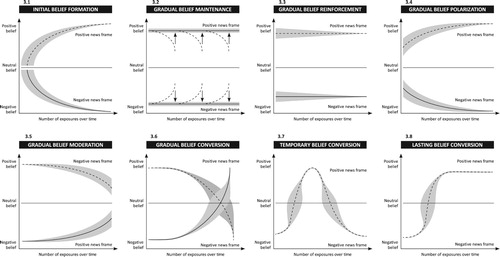

Bookkeeping, conversion and subtyping offer a basis for understanding media effects through the lens of specific short-term and long-term belief dynamics. Extending upon these general principles of schema accommodation, as well as previous typologies of communication effects (Matthes, Citation2007; Perse & Lambe, Citation2017; Potter, Citation2012; Scheufele, Citation2004), proposes a set of distinct media effect dynamics that manifest over a longer period of time only. Long-term, in this sense, refers to a comprehensive conceptualization of unique dynamics of influence, allowing for combinations of effect cumulation and non-linearity across time.

Figure 3. Long-term as effect dynamics.

Note: Each graph illustrates long-term effect dynamics of being repeatedly exposed to a negative or positive news frame. Variables displayed include belief position (positive, neutral, negative), belief certainty (wider bounds = lower certainty), and number of exposures over time to either a positive of negative news frame.

To illustrate the variety of distinct long-term effect dynamics, displays what happens to citizens’ societal beliefs when they are repeatedly exposed to belief consistent or inconsistent news coverage over time. The typology builds on framing terminology to illustrate the key factors at work, yet it provides a generic understanding of media effects on societal beliefs. Four variables are highlighted in the figure: (1) Belief position along the y-axis refers to whether citizens hold positive or negative perceptions about specific societal conditions – relating for instance to crime, health care, the economy or immigration; (2) News frame refers to whether citizens are exposed to positively or negatively framed news coverage of the specific issue; (3) Belief certainty, reflected by the grey-shaded area surrounding the black belief position lines, refers to the certainty with which citizens hold a particular position; (4) Time along the x-axis refers to the number of over-time exposures to specific news frames. The eight types of long-term media effects outlined are to be thought of as theoretical constructs in the sense that they are ‘cleaned’ from any third variables that may condition these effect dynamics (a topic discussed in the next section).

First, initial belief formation (Figure 3.1) describes situations when a new belief object appears on the media agenda. With no prior object-specific beliefs, citizens initially become heavily reliant on cues from the media. This situation is equivalent to having no (or very rudimentary) schemas in specific domains – which lowers cognitive resistance barriers and opens for influence (Crocker et al., Citation1984). Depending on the dominant news frame, beliefs will quickly adjust in a specific direction through establishing new schemas or links between schemas (Scheufele, Citation2004). The fact that citizens lack object-specific beliefs will leave them highly susceptible to strong initial effects, which gradually weaken as the store of object-specific considerations accumulates and schemas become more well-developed. Since belief positions crystalize with repeated exposure, belief certainty increases as well – as illustrated by the narrower certainty margin around the position line.

Second, also outlines two effects on belief position stability. Gradual belief maintenance (3.2) operates as a reminder effect (Asp, Citation1986; Matthes, Citation2007). Through repeated frame exposure, people are constantly updated on beliefs they already hold. As noted by Matthes (Citation2007), ‘when media framing does not change, individuals will most likely retrieve the same information as before, simply because they remember the same media frames as before’ (p. 66), but ‘in the absence of additional communication, framing effects rapidly decay over time’ (Chong & Druckman, Citation2010, p. 665). The maintenance effect is a function of the accessibility mechanism; continuous schema activation over time can potentially even result in chronic accessibility (Koch & Arendt, Citation2017). Gradual belief reinforcement (3.3) also reflects belief position stability. In this case, however, repeated exposure also increases the weight attached to certain object-specific beliefs. As citizens encounter belief-congruent communication, they gradually become more certain about those beliefs, making them harder to change (Potter, Citation2012; Slater, Citation2007).

Third, five distinct media effects related to belief change are illustrated. In the case of gradual belief polarization (3.4), prior belief positions successively turn more extreme in response to congruent news frames. Such developments also come with increasing belief certainty. The opposite effect, gradual belief moderation (3.5), takes place when people’s baseline beliefs become less extreme over time. This moderation occurs when people are exposed to belief-incongruent news frames over time: extreme beliefs weaken into more moderate beliefs, certainty into uncertainty. The contrasting curved lines reflect that baseline belief position and certainty condition the trajectory of the change. It takes more effort and time to initiate changes from strong belief positions (due to higher levels of belief strength), than initiating changes of weakly held beliefs (Chong & Druckman, Citation2012; Matthes & Schemer, Citation2012). In the case of gradual polarization, individuals respond quickly to belief-congruent news frames, followed by diminishing marginal effects. Gradual belief moderation displays the opposite pattern, with strongly held beliefs being more resistant to incongruent news frames initially, followed by growing marginal effects. In both instances, however, citizens hold on to their initial positions.

Societal beliefs can also undergo change through conversion effects. Gradual belief conversion (3.6) is an extension of the moderation effect, in which citizens eventually also take on a different belief position: from negative to positive or from positive to negative. Again, the curved lines reflect that prior belief positions are initially insensitive to exposure to repetitive incongruent frames. At a certain tipping point, the cognitive resistance barriers weaken and susceptibility to belief changes increases. While gradual belief conversion describes a slow change process that accumulates over time, the sudden temporary belief conversion (3.7) effect outlines a rapid belief dynamic triggered by some external shock or event. In this case, a baseline belief position quickly changes from negative to positive (or vice versa) in response to a powerful incongruent news frame. Though such rapid ‘all-or-none’ conversion may be rather unusual (Balogun & Johnson, Citation2004; Crocker et al., Citation1984), these effects are driven by the combination of high levels of uncertainty, triggered by unexpected shocks to belief systems and particularly strong news frames (Chong & Druckman, Citation2007; Matthes, Citation2007; McCombs, Citation2014). Without continued support to sustain the belief conversion, the effect dissipates and gradually regresses to baseline (Koch & Arendt, Citation2017). On the contrary, a sudden lasting belief conversion (3.8) effect, which follows the same initial pattern as the temporary effect, also leads to a persistent conversion.

Taken together, this way of conceptualizing long-term draws attention to the different belief dynamics that media effects may induce – and which remain largely invisible in a short-term perspective. Effect cumulation, non-linearity and timing are core factors of this dynamic approach to long-term effects. The typology proposed in provides a framework for distinguishing various dynamics that manifest over time only.

***

In sum, these three conceptualizations – effect duration, mechanisms, and dynamics – represent distinct ways of addressing long-term media effects in communication research, with implications for theory, research design and measurements. While not mutually exclusive, they relate to specific research questions ranging from (1) the duration of schema activation, (2) the mechanisms behind schema accommodation, to (3) the dynamics through which schemas accommodate.

Factors influencing long-term media effects: a multilevel framework

After conceptualizing long-term media effects as questions of duration, mechanisms, and dynamics, we now turn to factors that influence such effects. In line with most recent understandings of media effects (Lecheler & de Vreese, Citation2018; Valkenburg & Peter, Citation2013), and theories of schema development (Crocker et al., Citation1984; Matthes, Citation2008), we suggest that long-term effects are conditional on three groups of factors: (1) content factors at the news story level, (2) recipient factors at the individual level and (3) contextual factors surrounding the news exposure situation. While the list of specific factors cannot be exhaustive – alternative frameworks already exist in the media effects literature, although developed for different purposes – we focus on variables that are the most relevant from a schema theory and long-term effects perspective.

The starting point is a typical everyday news encounter: citizens read, hear or watch a particular news story (irrespective of the platform). In this situation, perceptions are formed through an interaction between content and recipient characteristics (Perse & Lambe, Citation2017; Valkenburg & Peter, Citation2013). Using the schema framework outlined above, ‘as people comprehend media stories, they construct situation models of the specific stories. In addition they construct mental models of larger events’ (Roskos-Ewoldsen et al., Citation2009, p. 86). Whether these on-the-fly impressions leave enduring imprints on cognitive schemas is however less clear. Effects of single news encounters typically dissipate rapidly, leading people to quickly forget what they read or hear about (Chong & Druckman, Citation2010; Koch & Arendt, Citation2017; Mitchell, Citation2012), but a variety of factors condition this process.

Content-level factors

Factors at the content level refer to message characteristics of news items. We emphasize three characteristics of news content that might be particularly important for long-term influences: frame strength (compelling arguments), negativity and exemplification. From a long-term effects perspective, these content factors are likely to be relevant for each of the conceptualizations identified above.

Frame strength (compelling arguments)

News coverage influences issue interpretations by suggesting issue-specific emphasis frames, but not all frames are equally effective. The concept of ‘frame strength’ – similar to compelling arguments in attribute agenda-setting research (McCombs, Citation2014) – focuses on qualities of frames that make them more persuasive in opinion formation (Aarøe, Citation2011; Chong & Druckman, Citation2007a; Matthes, Citation2007). Strong frames focus on considerations that are both available and applicable among the public, while weak frames emphasize unavailable or irrelevant considerations (Chong & Druckman, Citation2007a, Citation2007b). In the short run, frame strength should have an immediate impact on belief formation when recipients consume and process news (illustrated in and ). In the long run, frame strength should be considered endogenous, however – as a function of media effects itself. Since both consideration availability and applicability depend on long-term cumulative and consonant news exposure (Koch & Arendt, Citation2017; Scheufele, Citation2004), gradual schema accommodation also changes the strength of frames (e.g. gradual effect dynamics in ).

Negativity

Another content characteristic assumed to elicit strong effects is negativity – a widespread feature of news coverage (Lengauer et al., Citation2012; Soroka et al., Citation2019). Given that people have a general preference for negative information and that such information weigh more heavily in impression formation than positive information (Soroka & McAdams, Citation2015), negativity is expected to influence effect duration by yielding stronger effects (e.g. ). In a review of framing effects, Lecheler and de Vreese (Citation2016) note that ‘negative news frames are likely to have stronger and therefore longer-lasting effects on opinions than positive news frames’ (p. 13). Similarly, using a psychophysiological experimental approach, Soroka and McAdams (Citation2015) conclude that ‘negative news content is likely to have a greater, and possibly more enduring, impact than positive news content’ (p. 13; see also Soroka et al., Citation2019). Yet, the extent to which these mostly emotional and attitudinal reactions impact cognitive schemas and beliefs about society is less clear.

Exemplification

Exemplification theory suggests that beliefs about society are heavily influenced by exemplars. First, concrete, vivid and emotional exemplars have a memory advantage compared to more abstract base-rate information when people assess the probability of real-world events (Aarøe, Citation2011; Shrum, Citation2009; Zillmann, Citation1999;). Second, exemplars attract attention and are more easily remembered. From a schema perspective, the ‘more memorable the information, the more likely it may be to influence the schema’ (Crocker et al., Citation1984, p. 215). Studies also relate exemplar effects to sleeper effects. The impact of vivid and attention-grabbing exemplars grows stronger over time, and these ‘[s]leeper effects are most likely to occur in the case of threatening and emotionally laden images’ (Bigsby et al., Citation2019, p. 276; see also Appel & Richter, Citation2007) – relating most clearly to effect duration and mechanisms of schema accommodation ( and ). Studies that address this over-time sleeper effect process are still few, according to a recent meta-analysis (Bigsby et al., Citation2019).

Recipient-level factors

In addition to content factors, cognitive approaches emphasize the interaction between message characteristics and individual-level recipient factors (Crocker et al., Citation1984; Perse & Lambe, Citation2017; Scheufele, Citation2004; Valkenburg & Peter, Citation2013). Individual-level factors are crucial since they influence not only schema activation, but assimilation and accomodation as well, leading either to long-term belief maintenance and reinforcement or to various forms of belief change (). Which schemas that are activated by a news story greatly influence information processing and issue interpretation – and which schemas that are activated and accessible depend on individual-level trait and state factors. We focus on three individual-level trait and state factors: information processing strategies, expertise and resonance.

Information processing

How citizens’ process the news they are exposed to is crucial for belief formation in general, and the duration and dynamics of long-term effects in particular ( and ). Two approaches illustrate the role of information processing.

First, dual processing theories, such as the elaboration likelihood model (ELM), suggest differential effects depending on whether information is processed through the central or peripheral route (Petty et al., Citation2009; Petty & Cacioppo, Citation1986). Central processing involves careful cognitive examination of a message in relation to prior beliefs, knowledge, experiences and values – to assess the merits of an argument or statement. Peripheral processing, in contrast, is based on low cognitive engagement, relying on automatic assessments of simple context cues. Central route processing generates more enduring belief effects, as well as greater resistance to subsequent belief-incongruent communication than peripheral processing (Holbert et al., Citation2010; Perse & Lambe, Citation2017). At the same time, both routes may well lead to sudden conversion effects: While central processing is likely to generate sudden lasting conversion effects (e.g. Figure 3.8), peripheral processing will follow a temporary conversion dynamic (e.g. Figure 3.7). The ELM also explains sleeper effects whenever a message is processed thoroughly (central route) but rejected based on a low source trust cue (peripheral route). As the peripheral cue dissipates from memory, the initial processing leads to gradual message acceptance (Petty et al., Citation2009).

Second, the distinction between memory-based (MB) and on-line (OL) opinion formation provides an alternative approach to the study of long-term media effects (Hill et al., Citation2013; Lodge et al., Citation1995). According to the MB model, people store pieces of information as they consume news, without forming an overall object judgement. When subsequently asked about their opinion, they construct an assessment by retrieving considerations accessible from short-term memory at the time. According to the OL model, people keep and continuously update a global object assessment as an online tally when consuming news. The tally is immediately stored in long-term memory, while the specific considerations making up the summary assessment are forgotten. MB and OL processing influence the duration and persistence of communication effects (Bizer et al., Citation2006; Chong & Druckman, Citation2010; Matthes, Citation2007).

Taken together, information processing that favors beliefs formed with greater certainty – central route or OL processing – is likely to contribute to more persistent media effects as illustrated, for example, in Figures 3.3, 3.4 and 3.8 (Chong & Druckman, Citation2010; Matthes & Schemer, Citation2012). Such effortful processing will also increase the likelihood that situation models created on the fly have lasting imprints on more abstract levels of schemas (). However, few citizens hold online tallies of strong beliefs on many issues, making memory-based processing and situation model effects more common (Chong & Druckman, Citation2010; Hill et al., Citation2013).

Expertise

Belief certainty and strength are related to expertise. Similar concepts frequently referred to in the media effects literature are knowledge and sophistication. As noted above, expertise varies both between individuals and across domains. High levels of expertise are equal to having more well-developed cognitive schemas, compared to having rudimentary or no domain-specific schemas (aschematic). Experts hold more information on a given topic. Their knowledge is also better integrated and organized: more concepts and stronger links between those concepts (Crocker et al., Citation1984; Fiske et al., Citation1983). The schemas of experts contain a higher quantity of well-integrated chunks of information and substantially more schema-consistent information, too. As a consequence, experts are more resistant than novices to belief conversion in the face of incongruent news coverage (e.g. Figures 3.7 and 3.8). Though subtyping occurs continuously, contributing to schema development and differentiation, these processes will primarily promote gradual belief maintenance and reinforcement (Matthes, Citation2008) (e.g. Figures 3.2 and 3.3). With more strongly held beliefs comes greater resistance to change. Whenever schemas are less developed – such as among domain-specific novices or when new objects appear on the media agenda – beliefs are highly sensitive and quickly adapt to the dominant media frame (e.g. Figure 3.1).

Resonance

News frames that fit preexisting schemas will always have a big advantage over schema-inconsistent frames. Two resonance dimensions emphasized in the media effects literature are particularly important. First, value resonance refers to the congruence between identity-relevant beliefs and attitudes and content characteristics. A range of consistency theories, such as cultural cognition (Kahan et al., Citation2011), motivated reasoning (Taber & Lodge, Citation2006) and the reinforcing spirals model (Slater, Citation2015) emphasize the importance of various identity-relevant attitudes (ideology, life-style, religion, etc.) in the selection and interpretation of facts. The more strongly anchored beliefs are in personal, social or political identities, the more resistant they are to change (Bartels, Citation2002; Gaines et al., Citation2007). Second, experience resonance is highlighted in the cultivation and agenda-setting literatures. Since cognitive schemas continuously develop in response to experiences (Crocker et al., Citation1984; Fiske & Taylor, Citation2017), the accumulated knowledge from past personal experiences exerts a significant impact on what people bring to a given news exposure situation. Looking at framing effects as an example, the role of such experiences should matter in two ways (McCombs, Citation2014; Morgan & Shanahan, Citation2010; Mutz, Citation1998). On the one hand, when people lack experiences (unobtrusive issues), their reliance on media increases, and beliefs about society are more likely to adjust to media coverage. On the other hand, when people have personal experiences (obtrusive issues), belief dynamics depend on the congruency between those experiences and media coverage. While experience resonance facilitates frame acceptance, media effects in situations of incongruency depend on how people weigh their personal experiences relative to media coverage.

Context-level factors

The final group of factors extends beyond the immediate news exposure situation. Context refers to the environmental and situational characteristics in which news consumption and elaboration take place. Contextual factors are relevant for understanding how messages encountered in the media are validated in everyday life and social settings – by either supporting or weakening beliefs through various effect dynamics over time (). Here, we discuss repetitive and competitive news exposure as well as social network communication as crucial context-level factors.

Repetitive exposure

Discussions about long-term media effects largely revolve around repetitive and cumulative content exposure over extended periods of time. Cultivation and agenda-setting are built on the notion of cumulation (Koch & Arendt, Citation2017; Perse & Lambe, Citation2017) and repeated exposure to consonant news frames is also a key mechanism behind schema change (Scheufele, Citation2004). With respect to beliefs about society in particular, two competing arguments are found in the literature. On the one hand, repetition is the basis for the illusory truth effect: repeating a message increases the perceived accuracy or validity of a claim. Both message familiarity and processing fluency have been suggested as mechanisms behind illusory truth (or mere exposure) effects (Moons et al., Citation2009; Pennycook et al., Citation2018), and repetitive exposure increases belief accessibility, certainty and strength (Druckman et al., Citation2012; Slater, Citation2015).

On the other hand, Petty and Cacioppo (Citation1986; see also Cacioppo & Petty, Citation1989) suggest a two-stage curvilinear relationship between message repetition and acceptance. Initially, repetition increases opportunities to learn about the message. Beyond this initial stage, additional repetition induces tedium and psychological reactance, leading to counterarguing and skepticism. At the same time, experimental studies suggest that repetitive exposure to one-sided content generate stronger – though not necessarily cumulative – effects than a single exposure (Druckman et al., Citation2012; Lecheler et al., Citation2015; Lecheler & de Vreese, Citation2013), contributing to belief stability. As shown in , however, repetitive exposure is not confined to stability effects, but can contribute to various forms of gradual moderation, polarization and conversion effects as well.

Competitive exposure

While message repetition may be a powerful force behind long-term stability effects (see, e.g. Figures 3.2 and 3.3), news coverage of many societal problems is characterized by competitive media messages and framing environments. Though studies suggest that competitive environments neutralize media effects as people selectively accept the frames that match their predispositions (Chong & Druckman, Citation2010; Lecheler & de Vreese, Citation2018), important qualifications are needed here. First, neutralizing effects on global judgements are not equal to no effects. The content of thoughts is likely to change through continuous belief updating (Brewer & Gross, Citation2005; Crocker et al., Citation1984). Second, compared to simultaneous competitive frame exposure, sequential counter-messages over time appear to favor recency over frequency effects, especially among low-effort information processors (Chong & Druckman, Citation2010; Mitchell, Citation2012). Third, however, extended time delays between the most recent exposure and effect measurement may lead to recency-frequency reversal, with beliefs regressing to a baseline defined by frequent and cumulative exposure (Koch & Arendt, Citation2017; Lecheler & de Vreese, Citation2013). Similarly, studies suggest that an initial frame generating strong effects on beliefs formed with greater certainty will both persist subsequent counter-framing and encourage successive belief-consistent selective exposure (Chong & Druckman, Citation2010; Druckman et al., Citation2012; Kepplinger et al., Citation2012; Matthes & Schemer, Citation2012). Fourth, competitive framing can generate backfiring and contrast effects whenever a strong or compelling argument competes with a weak argument, ‘pushing the recipient further in the direction of a strong frame than if she or he had been exposed only to the strong frame’ (Chong & Druckman, Citation2007, p. 640). Thus, counter-message extremity matters, since moderately incongruent information receives more attention and consideration, instead of being rejected right away.

Social networks

Individuals’ news consumption does not take place in social isolation or in a vacuum. Citizens are nested in social networks of family, friends, colleagues and acquaintances that function as sources of information and as filters in larger communication flows – both offline and on social media. Through everyday political conversations, beliefs and attitudes are socially validated and negotiated in relation to group norms. As such, media effects are continuously moderated by social networks (Mutz & Young, Citation2011; Schmitt-Beck, Citation2003). According to the filtering hypothesis, interpersonal communication functions in a similar manner as predispositions, by telling people about the validity of media messages and whether these should be accepted (Schmitt-Beck, Citation2003; Song & Boomgaarden, Citation2017). Prior research suggests that interpersonal communication can moderate media effects, such as agenda-setting, framing and reinforcing spirals (Druckman & Nelson, Citation2003; Song & Boomgaarden, Citation2017; Wanta & Wu, Citation1992).

Two aspects of social networks are important to consider. First, extensive research shows that political talk primarily takes place within strong-tie relationships, such as among family members and close friends (Ekström, Citation2016; Mutz & Young, Citation2011). Second, these strong-tie networks are typically characterized by homogeneity. As noted by Schmitt-Beck and Lup (Citation2013), the ‘homophily principle is a powerful force in people’s interpersonal communication’ […] and hence ‘most political talking occurs between like-minded souls and consists in exchanges of mutually agreeable statements’ (p. 519). The argument is that homogenous networks either weaken or strengthen media influence, depending on message-network congruency.

A summary framework model

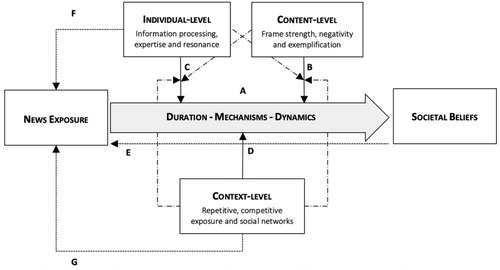

The factors outlined above provide a multilevel framework for analyzing long-term media effects on citizens’ beliefs about society. combines the moderators of long-term media effects (Paths B, C, and D) with our conceptualization of these effects as a matter of duration, mechanisms and dynamics (Path A).

Figure 4. Factors conditioning long-term media effects on societal beliefs.

Note: Paths highlighted in the model: A = Focal relationship; B = Content-level moderators; C = Individual-level moderators; D = Context-level moderators; E = allowing for potential reciprocity; F = Selective exposure driven by individual-level characteristics; G = Contextual factors behind news selection and exposure. Additional dashed lines = potential joint influences of moderators.

Following the empirical overview and synthesis of factors, we suggest four broad propositions derived from the model. Depending on the specific theoretical point of departure and explanatory factors emphasized, long-term media effects may have different sources generated by distinct mechanisms and processes:

Long-term effects driven by extrinsic powerful messages (Path B). This argument emphasizes content characteristics as the driving mechanism. Here, the relationship between message characteristics and long-term effects is understood in terms of effect strength and effect duration. Since certain content induces strong initial media effects, these effects will generally linger over a longer period of time.

Long-term effects driven by intrinsic motivation to process news (Path C). This argument focuses on individual-level motivation as the driving mechanism. According to this reasoning, long-term effects emerge as a result of high intrinsic motivation to seek out, attend to and elaborate on media messages. Different from the content argument above, the information processing argument also includes gradual elaborative processes that extend beyond the instantaneous exposure situation, connecting specific situation models to accommodation of more abstract levels of cognitive schemas. As such, effects of intrinsic motivation may flourish over longer periods of time – and generate different subsequent belief dynamics than content-driven effects.

Long-term effects driven by continuous contextual support (Path D). This argument emphasizes situational and environmental factors surrounding news exposure as the driving mechanisms. Either through repetitive exposure to consonant and one-sided news coverage or filtered through homogenous and consensual social networks, long-term effects on beliefs about society may be sustained by consistent external support. This way of understanding long-term influences is identical to the general mechanisms behind cultivation and socialization effects. A constant flow of belief-consistent communication is a low-motivation source of long-term effects, supporting temporary and eventually chronic belief accessibility.

Long-term effects conditioned by multiple antecedents. To understand fully the nuances of various effect processes, none of the factors singled out can be studied in complete isolation. Rather, long-term media effects need to be analyzed using an integrative approach that comprehensively accounts for factors at various levels of analysis. The dashed lines in highlight this point by illustrating potentially simultaneous influences of content-, recipient- and context-level factors. For the sake of simplicity, only moderation effects are included in the model. To complete the picture, arrows have also been added to recognize reciprocal effects of societal beliefs on news exposure (Path E), as well as the important role that individual- and context-level factors play for media selection mechanisms (Paths F and G).

Toward an integrative approach of studying long-term media effects

The purpose of this article has been to provide a comprehensive theoretical conceptualization of long-term media effects on societal beliefs. The contrast between theoretical claims about long-term influences on the one hand, and empirical research on the other hand, has been noted in a number of field reviews: ‘considering the amount of research that has been conducted on media effects, it is astonishing how little is known about the cumulation and duration of these effects’ (Koch & Arendt, Citation2017, p. 8; see also Perse & Lambe, Citation2017; Potter, Citation2014; Tewksbury & Scheufele, Citation2009). Following an overview of empirical research, we used schema theory to propose and develop three distinct conceptualizations of long-term media effects: as a matter of (a) effect duration, (b) effect mechanisms and (c) effect dynamics. In addition, we presented a multilevel framework on antecedents of long-term media effects – accounting for the conditional and integrative nature of influences on such effects. Our conceptualization and multilevel framework address some long-standing issues in the field of media effects research and serve as a point of departure for future research.

Most importantly, we address questions relating to the ‘(new) era of minimal effects’ controversy (Bennett & Iyengar, Citation2008; Holbert et al., Citation2010). By proposing and specifying a broader conceptualization of long-term media effects, the article outlines a variety of effect mechanisms and dynamics anchored in schema theory that have been largely neglected in previous research. While longitudinal studies are not uncommon in the field, few have a comprehensive theoretical focus on long-term effects. Research questions relating to optimal time lags and effect duration are important, but they represent a rather narrow approach for understanding the full range of potential influences. Failure to adequately account for the diverse nuances of the dependent variable – societal beliefs – as well as how these are updated over time in response to media coverage, is likely to be a main reason for minimal effects findings (Holbert et al., Citation2010; Perse & Lambe, Citation2017). A similar point can be made with respect to the independent variables – or how the causal effect processes are theorized and empirically addressed. A schema theory perspective particularly emphasizes the conditionality of media effects as an interaction between content and recipient level factors. Failure to account for these conditional factors has recently been noted as another main reason behind weak media effects (Lecheler & de Vreese, Citation2018; Perse & Lambe, Citation2017; Valkenburg & Peter, Citation2013). The multilevel framework presented here provides a path forward suggesting how factors at different levels of analyses condition long-term media effects on societal beliefs. These considerations call for a more integrative focus in research on long-term media effects.

Future studies should go beyond effect duration as the main approach to analyzing long-term effects. Focusing on the mechanisms through which situation models translate into more abstract levels of cognitive schemas, and/or the broader variety of effect dynamics that manifest only over more extended periods of time, calls for a more comprehensive account of the how news media influence citizens’ societal beliefs. First, by distinguishing between transient, enduring and persistent media effects (Mitchell, Citation2012), the mechanisms approach focuses on research questions relating to when and how more specific and momentary mental representations formed during news exposure lead to accommodation of higher-order cognitive schemas. Second, the proposed typology of eight distinct effect dynamics provides a direction for addressing research questions concerning the formation, maintenance, gradual adjustment and conversion of beliefs. Attention should be paid to the time-dependency, cumulation and non-linearity that define these effect dynamics.

Ideally, this research should be conducted using an integrative approach. By outlining factors at the (a) content, (b) individual and (c) context level, we have suggested a multilevel framework for understanding long-term media effects. In contrast to previous empirical studies on beliefs, the framework calls for more integrative work on how these factors interact. The conditional role of social networks and personal experience appears particularly important for future research on long-term effects on societal beliefs. Another implication relates to the distinction between extrinsic and intrinsic sources behind long-term effects. Long-term influences may be driven either by strong content effects, personal motivations and/or contextual support. Thus, long-term effects can emerge and sustain also in the absence of strong information processing motivations. Being highly motivated to seek out and cognitively process information is one route to long-term media effects – and perhaps the most important – but it is certainly not the only one.

It should be noted that it has been our ambition to provide a generic conceptualization and framework for future studies on long-term effects. Though the focus has been on societal beliefs in a broad sense, the arguments based on a schema theory are relevant also for attitude formation more generally (Chong & Druckman, Citation2007; Fiske & Taylor, Citation2017; Slater, Citation2015). Media effect theories, such as agenda-setting, cultivation and framing, ultimately focus on societal perceptions and issue interpretations, but these effects are also assumed to impact attitudinal outcomes (Matthes & Schemer, Citation2012; McCombs, Citation2014). Furthermore, the conceptualization and framework are intended to be platform neutral. Whether citizens consume news by reading printed or online newspapers, listening to radio or podcasts, watching television or getting recommendations through social media, does not affect the general applicability of our arguments. Use of different platforms may of course influence how particular effect dynamics play out, but this platform difference can also be addressed using the proposed framework. A similar point can be made concerning the distinction between active and passive modes of news use. This factor is likely to be crucial for long-term effects, and it is subsumed under the broader category of information processing motivations in our multilevel framework. Thus, our ambition is to provide a general conceptualization and framework through which more specific research questions and mechanisms can be developed and tested.

Taken together, this article calls for more integrative research on long-term media effects. By considering a broader conceptualization of long-term influences – focused on mechanisms of schema accommodation and particular effect dynamics – we gain a better understanding of the ‘what, when, and how’ of both short- and long-term effects. Though almost a century has passed since Lippmann’s (Citation1922/1997) influential book on public opinion, research on media effects continues to develop. Today’s concerns regarding misperceptions, belief polarization and ‘fake news’, highlight the importance of analyzing how citizens’ beliefs are shaped over time in an increasingly fragmented media environment. We, therefore, hope that the review presented here will encourage future work on long-term media effects.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The complete list of articles is available from authors.

References

- Aarøe, L. (2011). Investigating frame strength: The case of episodic and thematic framing. Political Communication, 28(2), 207–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2011.568041

- Appel, M., & Richter, T. (2007). Persuasive effects of fictional narratives increase over time. Media Psychology, 10(1), 113–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213260701301194

- Asp, K. (1986). Mäktiga massmedier: studier i politisk opinionsbildning. Akademilitteratur.

- Balogun, J., & Johnson, G. (2004). Organizational restructuring and middle manager sensemaking. The Academy of Management Journal, 47(4), 523–549. https://doi.org/10.5465/20159600

- Bartels, L. M. (2002). Beyond the running tally: Partisan bias in political perceptions. Political Behavior, 24(2).

- Bennett, W. L., & Iyengar, S. (2008). A new Era of minimal effects? The changing foundations of political communication. Journal of Communication, 58(4), 707–731.

- Bigsby, E., Bigman, C. A., & Gonzales, A. M. (2019). Exemplification theory: A review and meta-analysis of exemplar messages. Annals of the International Communication Association, 43(3), 273–296. https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2019.1681903

- Bizer, G., Tormala, Z., Rucker, D., & Petty, R. (2006). Memory-based versus online pro-cessing. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 42(5), 646–653. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2005.09.002

- Brewer, P., & Gross, K. (2005). Values, frames, and citizens’ thoughts about Policy issues: Effects on content and quantity. Political Psychology, 26(6), 929–948. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2005.00451.x

- Cacioppo, J. T., & Petty, R. E. (1989). Effects of message repetition on argument processing, recall, and persuasion. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 10, 3–12.

- Cappella, J., & Jamieson, K. (1997). Spiral of cynicism. Oxford University Press.

- Chong, D., & Druckman, J. (2007a). A theory of framing and Opinion formation in competitive elite environments. Journal of Communication, 57(1), 99–118. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2006.00331_3.x

- Chong, D., & Druckman, J. (2007b). Framing theory. Annual Review of Political Science, 10(1), 103–126. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.10.072805.103054

- Chong, D., & Druckman, J. (2010). Dynamic Public opinion: Communication effects over time. American Political Science Review, 104(4), 663–680. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055410000493

- Chong, D., & Druckman, J. (2012). Counterframing effects. Journal of Politics, 75(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381612000837

- Conover, P., & Feldman, S. (1984). How people organize the political world: A schematic model. American Journal of Political Science, 28(1), 95–126. https://doi.org/10.2307/2110789

- Cottam, M., Mastors, E., Preston, T., & Dietz, B. (2016). Introduction to political psychology. Routledge.

- Crocker, J., Fiske, S., & Taylor, S. (1984). Schematic bases of belief change. In J. R. Eiser (Ed.), Attitudinal judgment (pp. 197–226). Springer.

- Druckman, J., Fein, J., & Leeper, T. (2012). A source of Bias in public opinion stability. American Political Science Review, 106(2), 430–454. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055412000123

- Druckman, J., & Nelson, K. R. (2003). Framing and deliberation. American Journal of Political Science, 47(4), 728–744. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-5907.00051

- Eagly, A., & Chaiken, S. (1998). Attitude structure and function. In D. T. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology (pp. 269–322). McGraw-Hill.

- Ekström, M. (2016). Young people’s everyday political talk: A social achievement of democratic engagement. Journal of Youth Studies, 19(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2015.1048207

- Fiske, S., Kinder, D., & Larter, M. (1983). The novice and the expert: Knowledge-based strategies in political cognition. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 19(4), 381–400. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1031(83)90029-X

- Fiske, S., & Taylor, S. (2017). Social cognition: From brains to culture. Sage.

- Gaines, B. J., Kuklinski, J. H., Quirk, P. J., Peyton, B., & Verkuilen, J. (2007). Same facts, different interpretations: Partisan motivation and opinion on Iraq. Journal of Politics, 69, 957–974.

- Hill, S., Lo, J., Vavreck, L., & Zaller, J. (2013). How quickly we forget: The duration of Persuasion effects from Mass communication. Political Communication, 30(4), 521–547. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2013.828143

- Holbert, L., Garrett, R. K., & Gleason, L. (2010). A new era of minimal effects? A response to Bennett and Iyengar. Journal of Communication, 60(1), 15–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2009.01470.x

- Kahan, D. M., Jenkins-Smith, H., & Braman, D. (2011). Cultural Cognition of scientific consensus. Journal of Risk Research, 14(2), 147–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2010.511246

- Kepplinger, H. M., Geiss, S., & Siebert, S. (2012). Framing scandals: Cognitive and emotional media effects. Journal of Communication, 62(4), 659–681. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2012.01653.x

- Kinder, D., & Kiewiet, R. (1981). Sociotropic politics: The American case. British Journal of Political Science, 11(2), 129–161. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123400002544

- Koch, T., & Arendt, F. (2017). Media effects: Cumulation and duration. The International Encyclopedia of Communication. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118783764.wbieme0217

- Lecheler, S., & de Vreese, C. H. (2011). Getting real: The duration of framing effects. Journal of Communication, 61(5), 959–983. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2011.01580.x

- Lecheler, S., & de Vreese, C. H. (2013). What a difference a day makes? The effects of repetitive and competitive news framing over time. Communication Research, 40(2), 147–175. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650212470688

- Lecheler, S., & de Vreese, C. H. (2016). How long do news framing effects last? A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Annals of the International Communication Association, 40(1), 3–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2015.11735254

- Lecheler, S., & de Vreese, C. H. (2018). News Framing effects. Routledge.

- Lecheler, S., Keer, M., Schuck, A., & Hänggli, R. (2015). The Effects of Repetitive news framing on Political opinions over time. Communication Monographs, 82(3), 339–358. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2014.994646

- Lengauer, G., Esser, F., & Berganza, R. (2012).: Negativity in political news: A review of concepts, operationalizations and key findings. Journalism, 13(2), 179–202. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884911427800

- Lippmann, W. (1922/1997). Public opinion. Free Press Paperbacks.

- Lodge, M., Steenbergen, M., & Brau, S. (1995). The responsive voter: Campaign information and the dynamics of candidate evaluation. American Political Science Review, 89(2), 309–326. https://doi.org/10.2307/2082427

- Matthes, J. (2007). Beyond accessibility? Toward an online and memory-based model of framing effects. Communications: European Journal of Communication Research, 32(1), 51–78. https://doi.org/10.1515/COMMUN.2007.003

- Matthes, J. (2008). Schemas and media effects. In W. Donsbach (Ed.), The International Encyclopedia of communication (pp. 4502–4508). Blackwell.

- Matthes, J., & Schemer, C. (2012). Diachronic framing effects in competitive opinion environments. Political Communication, 29(3), 319–339. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2012.694985

- McCombs, M. (2014). Setting the Agenda: The mass media and public opinion. Polity Press.

- Mitchell, D. G. (2012). It’s about time: The lifespan of information effects in a multiweek campaign. American Journal of Political Science, 56(2), 298–311. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2011.00549.x

- Moons, W., Mackie, D., & Garcia-Marques, T. (2009). The impact of repetition-induced familiarity on agreement with weak and strong arguments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96(1), 32–44. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013461

- Morgan, M., & Shanahan, J. (2010). The state of cultivation. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 54(2), 337–355. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151003735018

- Mutz, D. (1998). Impersonal influence. How perceptions of mass collectives influence Political attitudes. Cambridge University Press.

- Mutz, D., & Young, L. (2011). Communication and public opinion: Plus Ça change? Public Opinion Quarterly, 75(5), 1018–1044. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfr052

- Neuman, R. (1990). The threshold of public attention. Public Opinion Quarterly, 54(2), 159–176. https://doi.org/10.1086/269194

- Pennycook, G., Cannon, T. D., & Rand, D. G. (2018). Prior exposure increases perceived accuracy of fake news. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 147(12), 1865–1880. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000465

- Perse, E., & Lambe, J. (2017). Media effects and society. Routledge.

- Petty, R. E., Brinol, P., & Priester, J. R. (2009). Mass media attitude change: Implications of the elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. In J. Bryant, & M. D. Oliver (Eds.), Media effects: Advances in theory and research (pp. 125–164). Routledge.

- Petty, R. E., & Cacioppo, J. T. (1986). The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 19, 123–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60214-2

- Potter, J. (2014). A critical analysis of cultivation theory. Journal of Communication, 64(6), 1015–1036. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12128

- Potter, J. (2012). Media Effects. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Price, V., & Tewksbury, D. (1997). News Values and Public Opinion: A theoretical account of Media Priming and framing. In G. A. Barnett, & F. J. Boster (Eds.), Progress in Communication sciences (pp. 173–212). Ablex.

- Rhee, J. (1997). Strategy and issue frames in election Campaign coverage: A social cognitive account of framing effects. Journal of Communication, 47(3), 26–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1997.tb02715.x

- Roskos-Ewoldsen, B., Davis, J., & Roskos-Ewoldsen, D. R. (2004). Implication of the mental models approach for cultivation theory. Communications: European Journal of Communication Research, 29(3), 345–363. https://doi.org/10.1515/comm.2004.022

- Roskos-Ewoldsen, D., Roskos-Ewoldsen, B., & Carpentier, F. (2009). Media priming: An updated synthesis. In J. Bryant, & M. B. Oliver (Eds.), Media effects: Advances in theory and research (pp. 74–93). Taylor & Francis.

- Roskos-Ewoldson, D., & Roskos-Ewoldson, B. (2009). Current research in media priming. In R. L. Nabi, & M. B. Oliver (Eds.), The sage Handbook of media processes and effects (pp. 177–192). Sage.

- Scheufele, B. (2004). Framing-effects approach: A theoretical and methodological critique. Communications: European Journal of Communication Research, 29(4), 401–428. https://doi.org/10.1515/comm.2004.29.4.401

- Scheufele, D. (2000). Agenda-setting, priming, and framing revisited: Another look at cognitive effects of Political communication. Mass Communication and Society, 3(2–3), 297–316. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327825MCS0323_07

- Schmitt-Beck, R. (2003). Mass Communication, personal Communication and Vote choice. The filter hypothesis of media influence in comparative perspective. British Journal of Political Science, 33(2), 233–259. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123403000103

- Schmitt-Beck, R., & Lup, O. (2013). Seeking the soul of democracy: A review of recent research into citizens’ political talk culture. Swiss Political Science Review, 19(4), 513–538. https://doi.org/10.1111/spsr.12051

- Shrum, L. J. (2009). Media consumption and perceptions of social reality. In J. Bryant, & M. B. Oliver (Eds.), Media effects: Advances in theory and research (pp. 50–73). Routledge.

- Slater, M. (2007). Reinforcing Spirals: the mutual influence of media selectivity and media effects and their impact on individual Behavior and social identity. Communication Theory, 17(3), 281–303. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2007.00296.x

- Slater, M. (2015). Reinforcing Spirals model: Conceptualizing the relationship between media content exposure and the development and maintenance of attitudes. Media Psychology, 18(3), 370–395. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2014.897236

- Song, H., & Boomgaarden, H. (2017). Dynamic spirals put to test: An agent-based model of Reinforcing Spirals between selective exposure, interpersonal networks, and attitude polarization. Journal of Communication, 67(2), 256–281. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12288

- Soroka, S., Fournier, P., & Nir, L. (2019). Cross-national evidence of a negativity Bias in psychophysiological reactions to news. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 116(38), 18888–18892. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1908369116

- Soroka, S., & McAdams, S. (2015). News, politics, and negativity. Political Communication, 32(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2014.881942

- Taber, C., & Lodge, M. (2006). Motivated skepticism in the evaluation of political beliefs. American Journal of Political Science, 50(3), 755–769. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2006.00214.x

- Tewksbury, D., Jones, J., Peske, M., Raymond, A., & Vig, W. (2000). The interaction of news and advocate frames: Manipulating audience perceptions of a local public policy issue. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 77(4), 804–829. https://doi.org/10.1177/107769900007700406

- Tewksbury, D., & Scheufele, D. (2009). News Framing theory and research. In J. Bryant, & M. B. Oliver (Eds.), Media effects: Advances in theory and research (pp. 17–33). Routledge.

- Valkenburg, P., & Peter, J. (2013). The differential susceptibility to media effects model. Journal of Communication, 63(2), 221–243. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12024

- Wanta, W., & Wu, Y.-C. (1992). Interpersonal communication and the Agenda-setting process. Journalism Quarterly, 69(4), 847–855. https://doi.org/10.1177/107769909206900405

- Watt, J., Mazza, M., & Snyder, L. (1993). Agenda-setting effects of television news coverage and the effects decay curve. Communication Research, 20(3), 408–435. https://doi.org/10.1177/009365093020003004

- Wyer, R. S., & Radvansky, G. A. (1999). The comprehension and validation of social information. Psychological Review, 106(1), 89–118. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.106.1.89

- Zhu, J.-H., Watt, J., Snyder, L., Yan, J., & Jiang, Y. (1993). Public issue priority formation: Media agenda-setting and social interaction. Journal of Communication, 43(1), 8–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01246.x

- Zillmann, D. (1999). Exemplification Theory: Judging the whole by some of its parts. Media Psychology, 1(1), 69–94. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532785xmep0101_5