Introduction

After years of austerity, the people of Romania rebelled against its communist government despite the oppression of the hated and feared state secret police force, the Securitate. On Christmas day 1989 after a brief but violent uprising against the communist government president Nicolae Ceausescu and his wife were captured and executed, paving the way for reform and eventual membership in the European Union. It was only after the fall of the Ceaușescu government that western countries were able to see the devastating legacy of this evil man.

Background

In the aftermath of this revolution, it quickly became apparent that Romania had a major child health crisis to resolve. This catastrophe had arisen because Ceausescu tried to emulate the philosophy of the Soviet Union’s Joseph Stalin to increase the population of the country and implemented policies to outlaw abortion and contraception. Ceausescu famously declared, “Anyone who avoids having children is a deserter who abandons the laws of national continuity.”

As the country sank deeper and deeper into financial calamity throughout the 1980s one of the consequences of this austerity was child abandonment. Increasing numbers of parents simply discarded their unwanted children and put them into state-run institutions. By the end of the Ceausescu era, it was estimated that more than 100,000 children were institutionalized in state-run orphanages. In the final years of the regime, the economy of Romania was broken and the children in the state-run orphanages suffered extreme hardship with deterioration of nutrition, warmth, and caring. The eventual staff shortages ensured that although the physical needs of the children may have been partially met, their emotional needs were not!

Human Rights Watch (Citation2006), which investigates and reports on abuses happening in all parts of the world, published an account of what happened in those final years of the Ceausescu government. This report revealed that more than 7200 Romanian children and young people between ages 15 and 19 were still living with HIV, more than in any country in Europe. These so-called miracle children were the survivors among the more than 10,000 children who were infected with HIV between 1986 and 1991 in hospitals and orphanages as a direct result of the Ceausescu government policies. Lack of sterile equipment led to large numbers of children being exposed to contaminated needles. This situation was exacerbated by the use of so-called “microtransfusions” of unscreened blood which were used by the medical profession allegedly to boost the immune system of these abandoned children. In failing to use sterile needles, care staff aggravated the spread of horizontally acquired HIV infection among this group of vulnerable children (Flaitz, Citation2001).

Throughout this dark period, health-care professionals became academically isolated from their international peers with little access to evidence-based literature. Nurses in Romania then and still today are known as medical assistants and practice under the supervision and responsibility of a doctor. During the Ceausescu regime, the status of medical assistants (nurses) was not comparable to that of Western countries such as the United Kingdom and the United States. Lacking leadership and with a disenfranchised medical profession, the medical assistants were powerless to alleviate the suffering of abandoned babies and children (Steavenson, Citation2014).

Shortly after the revolution, the new government of Romania invited a range of non-governmental agencies (NGOs) into the country to help alleviate the looming child health-care crisis. Many of these NGOs were charities who specifically sought to help deal with the catastrophic warehousing of the thousands of abandoned children. The early visitors to these orphanages were shocked at the conditions, these children were living in. These institutions were overcrowded with too few staff to care for the children with some tied to their beds with no access to recreational play, toys, or a stimulating environment. Against this impoverished environment that left lasting and sometimes permanent psychological scars the children were simply too young to expedite change. However, one of these charities, Health Aid UK, led by nurse Anne McNicholas, set about acquiring houses where abandoned children, many with HIV, were rescued from the orphanages to live in a more normal home environment. For many, this was too late, as they were already 3 to 4 years old. Many of the Romanian orphans were subsequently adopted by western families. Now a group of academics from the University of Southampton and Kings College London have recently published research on some of these former children who were adopted by UK families in the wake of the fall of President Nicolae Ceaușescu. This longitudinal study has endeavored to elucidate how early experiences in early life shape individual development (Mackes et al., Citation2020).

Sensory deprivation in early childhood

There is a large body of literature on the effects of early life sensory deprivation and especially that related to maternal deprivation. As far back as 1951, John Bowlby (Bowlby, Citation1951) was articulating the crucial role that an attachment figure (normally the mother) was to normal development. He argued that disruption to the mother–child relationship in early life could lead to irreparable and irreversible consequences for the individual child’s development. Similarly, more than half a century later, Tomalski and Johnson (Citation2010) highlighted the importance of the child’s socioeconomic background on brain development with early sensory deprivation, an impoverished environment, and institutionalized care having negative sequalae, but especially those related to mental health.

The vintage and now seminal work of Bowlby is poignant given recent longitudinal research over a 20-year period from Israel. This new research indicates that preterm or low birthweight babies being nursed in incubators and being deprived of their mother’s touch during the early weeks of life may suffer long term and enduring emotional problems. This study compared outcomes from a cohort of 146 babies where 50% of them were allocated to a Kangaroo care group where they could have skin-to-skin contact with their mother without the incubator. The babies who did not receive Kangaroo care where the mother (or father) is enabled to cuddle the baby chest-to-chest and skin-to-skin fared less well emotionally when compared to those babies who benefited from this intervention. It is important to stress that many western countries including neonatal units in the United States and the United Kingdom do facilitate kangaroo care (Knapton, Citation2020).

Clearly, the lack of sensory stimulation/deprivation in early childhood can be devastating for the future wellbeing of children but it has been thought that if these children were subsequently placed in a loving and caring environment that some of these negative effects could be ameliorated.

Addressing the plight of Romania’s forgotten children

I was able to visit Romania about 18 months after the overthrow of Ceausescu in the summer of 1992. I accompanied the vice president of the Royal College of Nursing (RCN) in my capacity as the deputy chair of the society of pediatric nursing (now configured as a range of forums within the RCN) on a preliminary mission. The aim of this mission was to offer the medical assistants in the cities of Bucharest and Brasov, who were endeavoring to align themselves with the UK model of nursing, a series of lectures on recent concepts in nursing. My specific task was to make presentations on recent innovations in the care of sick children. We soon saw that it was not only children who were abandoned in the wake of the economic meltdown in Romania during the last years of the Ceaușescu regime but dogs also. Unable to afford the cost of food for these family pets the dogs were put out onto the streets and soon reverted to undomesticated behavior and began to forage in packs. Once when we were leaving the Marie Curie Hospital Bucharest in a dilapidated taxi with no functioning windows, we were chased by a large pack of dogs. The engine of the taxi was in its final stage of life and could barely outrun the dogs and when one of the snarling beasts tied to leap into the car through the opening window we only escaped being savaged by throwing ourselves into the well of the off-side rear seat. Gradually the speed of the car increased and we left the pack behind. During the early period after the revolution health authorities in Bucharest were spending huge amounts of money on buying rabies immune globulin prophylaxis for treating the large number of people being bitten by these wild dogs.

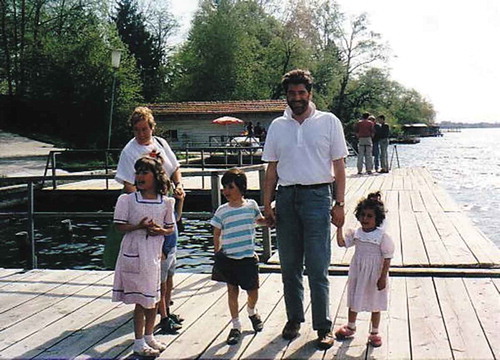

On our return to the UK, I was asked by the president of the RCN to lead a series of charitable missions to help the plight of sick children in the country including those infected with HIV (). My clinical and academic colleagues and I continued to visit Romania over the next five years and on each occasion we collected toys from various organizations but especially banks who gave us many packets of balloons (Glasper, Citation1999). When we first managed to get inside the institutions caring for these sick children in Bucharest we were shocked at the lack of emotional stimulation offered by the medical assistants who perceived their role to be primarily physical in nature (see for an example of the medical assistants’ badge). The children we saw were cared for in white cots in Nightingale type wards with white walls devoid of embellishment. The children sat in these cots totally devoid of toys with the sides up staring into space rocking backward and forward. Although many were toddlers they had little in the way of language acquisition and I remember vividly their eyes lighting up as I blew each of them a balloon to play with. (Children the world over simply adore balloons.) The following year, my colleagues and I ran a series of seminars in Bucharest and Brasov on the value of play for addressing sensory deprivation (Herron & Glasper, Citation1993).

Figure 1. Professor Glasper in the early 1990s with Anne McNicholas and some of the children from one of the charitable children’s homes set up to rescue HIV children from Romanian orphanages.

We knew that it was important for the medical assistants to fully understand the importance of play for children and young people. This is because play is the language of children, an essential tool through which they attain knowledge about themselves and the world around them. Play is a rich learning medium, and the ability to play develops earlier in children than the ability to communicate through language, making it a valuable communication tool for children of all ages. In context play is essential for all aspects of a child’s “normal” growth and development, enabling the child to develop emotionally, socially, physically, and intellectually. Play is an integral part of every child’s life and children with learning disabilities especially can benefit hugely from the use of therapeutic play strategies (Weaver & Groves, Citation2010).

However, simply altering the environment of care to incorporate play was never going to be the sole answer for helping the Romanian children who were abandoned in these institutions. It was clear that these children needed to be cared for in a more normal home type environment where play provision and one-to-one communication between the child and the carer could be guaranteed. Health Aid UK, one of the children’s charities operating in Romania during those early years after the revolution, did just that and opened a range of small houses with gardens where small groups of abandoned orphans with HIV could be cared for. In the intervening years, my colleagues and I were able to visit a selection of these homes where the care environment was so much different from the hospitals and orphanages. Here the children living in them were cared for by house “mothers” who acted in loco parentis and they thrived. I am still in touch with one of these children and this child is now married and a mother of two children herself! Although this little girl survived her early life ordeals, others were not so fortunate. In context, the Romanian Health Authority has acknowledged this HIV medical catastrophe and each infected person from that era now receives free antiviral therapy and a disability pension for life.

Early life deprivation in former Romanian orphans

Despite the commendable efforts of individuals and organizations to mitigate the effects of early life sensory deprivation, it appears at least for some of the affected Romanian children that these may be irreversible. The latest research conducted with former Romanian orphanage children has endeavored to investigate the impact on adult brain structure of severe but time-limited institutional deprivation in early life prior to them being subsequently adopted into nurturing families. These now young adults who participated in the research had been placed in Romanian institutions in their first few weeks of life. While in the institutions, these babies were subsequently malnourished and received minimal social contact and little stimulation. The time spent in institutions before adoption into families in the United Kingdom varied between 3 and 41 months. The researchers showed that in the group of young adults who had been adopted into British families, there were changes in brain volume linked to their early life deprivation which were statistically associated with lower IQ and greater attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptoms. Importantly this research has shown that structural brain changes in adulthood can be associated with the duration of deprivation experienced at a very young age (Mackes et al., Citation2020). Hence, despite the best efforts of charities operating in Romania such as Health Aid UK, the very early experiences of neglect and emotional deprivation in these groups of children have enduring and lifelong effects.

Conclusion

It is salutary to note that millions of children worldwide continue to live in non-familial institutions where they can be deprived of sensory stimulation. The evidence base now suggests that despite subsequent positive experiences, many children continue to be profoundly affected by early life sensory deprivation.

Key points

In the aftermath of the Romanian revolution, it quickly became apparent that the country had a major child health crisis to resolve.

Romania sank deeper and deeper into financial calamity throughout the 1980s and one of the consequences was child abandonment. Some parents simply discarded their unwanted children and put them into state-run institutions.

More than 10,000 children were infected with HIV between 1986 and 1991 in hospitals and orphanages as a direct result of Ceausescu government policies.

Health Aid UK, a children’s charity operating in Romania after the revolution, opened a range of small houses with gardens where small groups of abandoned orphans with HIV could be cared for.

Despite the best efforts of charities operating in Romania the very early experiences of neglect and emotional deprivation in these groups of children have enduring and lifelong effects.

References

- Bowlby, J. (1951). Maternal care and mental health [monograph]. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Flaitz, C., Wullbrandt, B., Sexton, J., Bourdon, T., & Hicks, J. (2001). Prevalence of orodental findings in HIV-infected Romanian children. Pediatric Dentistry, 23(1), 44–50.

- Glasper, A. (1999). An evaluation of five years’ work in Romania. Paediatric Nursing, 11(8), 32–35. doi:10.7748/paed.11.8.32.s24

- Herron, H., & Glasper, A. (1993). The birth of a new society. Peadiatric Nursing, 5(9), 22–23. doi:10.7748/paed.5.9.22.s15

- Human Rights Watch. (2006). “Life doesn’t wait”: Romania’s failure to protect and support children and youth living with HIV. New York, NY: Author.

- Knapton, S. (2020, February 18). Babies kept from mothers’ touch in earliest weeks have disadvantages in later life, study finds. The Telegraph. Retrieved from https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2020/02/18/babies-kept-mothers-touch-earliest-weeks-have-disadvantages/

- Mackes, N. K., Golm, D., Sarkar, S., Kumsta, R., Rutter, M., Fairchild, G., … Songua-Barke, E. J. S.; on behalf of the ERA Young Adult Follow-Up Team. (2020). Early childhood deprivation is associated with alterations in adult brain structure despite subsequent environmental enrichment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(1), 641–649.

- Steavenson, W. (2014, December 10). Ceausescu’s children. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/news/2014/dec/10/-sp-ceausescus-children

- Tomalski, P., & Johnson, M. H. (2010). The effects of early adversity on the adult and developing brain. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 23(2), 233–238. doi:10.1097/YCO.0b013e3283387a8c

- Weaver, K., & Groves, J. (2010). Play provision for children in hospital. In A. Glasper, M. Aylott, & C. Battrick (Eds.), Developing practical skills for nursing children and young people (pp. 72–88). London, UK: Hodder Arnold.