Abstract

This article examines the relationship between racism and environmental deregulation in President Trump’s first year in office. We collected data on all environmental events, such as executive actions at the federal level or Trump’s tweets. Likewise, we documented racist events targeting indigenous people, people of color, Muslims, and South Asians or Arabs. We found important differences in how these agendas unfolded: Environmental events were more likely to be concrete actions, whereas racist events were more likely to involve “noisy” rhetoric. The differing forms are not associated with particular levels of harm; rather, they suggest the unanticipated and complex ways in which racism intersects with environmental governance under neoliberal, authoritarian regimes. We argue that Trump’s “spectacular racism,” characterized by sensational visibility, helps obscure the profound deregulation underway. The white nation plays a critical role, as Trump uses spectacular racism to nurture his base, consolidate his power, and implement his agenda. Such an analysis expands how environmental racism is typically conceptualized. Key Words: environmental deregulation, spectacular racism, Trump, white nation.

本文检视特朗普总统上任第一年间, 种族主义和环境去管制之间的关系。我们搜集所有环境事件的数据, 诸如联邦层级的行政行动或特朗普的推文。我们同样记录针对原住民族、有色人种、穆斯林、以及南亚或阿拉伯人的种族歧视事件。我们发现, 这些议程开展的方式具有重要的差异:环境事件更倾向是具体的行动, 而种族歧视事件则更可能涉及“嘈杂的”修辞。不同的形式并非关乎特定程度的伤害;反之, 它们指向威权新自由主义政体下, 种族主义和环境治理交叉的非预期与复杂的方式。我们主张, 特朗普以轰动的可见度为特徵的“奇观种族主义”, 有助于掩盖正在进行中的深刻去管制。 特朗普运用奇观种族主义来培养其基层、巩固其权力并执行其议程时, 白人国族扮演了关键角色。此般分析扩展了环境种族主义一般被概念化的方式。关键词:环境去管制, 奇观种族主义, 特朗普, 白人国族。

Este artículo examina la relación entre racismo y desregularización ambiental durante el primer año de gobierno del presidente Trump. Recabamos datos de todos los eventos ambientales, tales como las acciones ejecutivas a nivel federal, o los tuits de Trump. También, documentamos eventos racistas enfocados contra gente indígena, gente de color, musulmanes y asiáticos del sur, o árabes. Encontramos diferencias importantes sobre la manera como estas agendas fueron desplegadas: Seguramente, los eventos ambientales fueron acciones concretas, en tanto que los eventos racistas muy probablemente se revistieron de retórica “ruidosa”. Las formas discrepantes no están asociadas con particulares niveles de daño; más que eso, sugieren el modo imprevisto y complejo como el racismo intersecta con la gobernanza ambiental bajo regímenes neoliberales y autoritarios. Sostenemos que el “espectacular racismo” de Trump, caracterizado por su despliegue sensacionalista, ayuda a ocultar la profunda desregulación que está en marcha. La nación blanca juega un rol crítico a medida que Trump usa el racismo espectacular para nutrir su base, consolidar su poder e implementar su agenda. Tal tipo de análisis amplía la gama de maneras como el racismo ambiental es típicamente conceptualizado.

This article examines the relationship between racism and environmental deregulation in President Trump’s first year. A hallmark of the Trump era (defined as his campaign and presidency) is his use of transgressive racism, such as declaring Mexicans rapists and introducing a Muslim ban. Geographers have analyzed how and why he has employed this strategy and its impacts (Gokariksel and Smith Citation2018; Inwood Citation2018; Page and Dittmer Citation2018). The profundity of transgressive racism, which we call spectacular racism, is akin to Nixon’s (Citation2011) “spectacular violence” in its visible and sensational nature (6, 13). Not surprisingly, Trump’s spectacular racism has shifted the U.S. racial formation. Racial formation is “the process by which social, economic and political forces determine the content and importance of racial categories, and by which they are in turn shaped by racial meanings” (Omi and Winant Citation1994, 61). Until recently, hegemonic racial culture was marked by political correctness and “neoliberal multiculturalism” (Melamed Citation2011), but it now coexists with overt white supremacy. Because the United States is a deeply racialized society, not only are all sites racialized but racial processes can produce a multitude of consequences—including unanticipated and seemingly unrelated ones. Thus, we explore how the shift in racial formation, specifically the ascent of spectacular racism, might have affected environmental governance. We do this by comparing how Trump’s environmental and racist agendas unfolded during his first year in office. The data, which include speeches, proposed legislation, and appointments, indicate that Trump’s spectacular racism drew massive media attention because of its transgressive nature, whereas his environmental agenda attracted far less scrutiny. Indeed, Trump's environmental agenda was extremely well-orchestrated and unfolded quietly. Regardless of intent, we suggest that Trump’s spectacular racism overshadowed environmental deregulation in his first year. Consequently, one of the many outcomes of spectacular racism has been to facilitate deregulation and a larger neoliberal agenda.

Such a reframing is important because it expands how racism is conceptualized within the discipline of geography and environmental justice. Within geography, racial analyses often focus on how racism affects people of color, rather than attending to the larger political culture (for exceptions, see Kobayashi and Peake Citation2000; Gilmore Citation2002; Inwood Citation2015; Bonds and Inwood Citation2016; Inwood and Bonds Citation2016; Pulido Citation2017, Citation2018). Within environmental justice, racism is usually conceptualized as the spatial relationship between environmental hazards and marginalized communities, including procedural justice (Schlosberg and Carruthers Citation2010; Yen-Kohl and The Newtown Florist Club Writing Collective Citation2016). Our analysis builds on critical environmental justice scholars seeking to expand the contours of environmental racism (Heynen Citation2016; Pulido Citation2016, Citation2017; Pellow Citation2017). We argue that Trump’s spectacular racism transformed the political environment by facilitating an authoritarian neoliberal regime, with profound consequences for the natural environment through deregulation. We do not claim that this was planned, although possible; rather, we trace two parallel processes to uncover unanticipated linkages.

We ask the following questions: What has been the role of spectacular racism during Trump’s first year? What has been the relationship between spectacular racism and environmental deregulation? Which populations have been targeted, and why? How has environmental deregulation occurred? We answer these questions by comparing two interconnected data sets: one list of environmental events and one of racist/anti-indigenous, anti-immigrant, and anti-Muslim/Arabs events (hereafter referred to as racist). Although we distinguish racist events from environmental ones for the sake of data collection and analysis, we acknowledge their somewhat fictitious nature. Despite such challenges, however, the data indicate that the two agendas have unfolded distinctly and that U.S. white supremacy is so pervasive that it affects seemingly “nonracial” phenomena.

Spectacular Racism and the White Nation in the Trump Era

The Trump era marks a shift in the racial formation. According to Melamed (Citation2011), the early twenty-first century was characterized by neoliberal multiculturalism, a form of antiracism in which race is dematerialized and severed from capitalism’s violence. Neoliberal multiculturalism, including political correctness, was delegitimized by the Trump campaign. Trump’s racist rhetoric, which affirms whiteness and connected emotionally, inspired intense media coverage precisely because of its transgressive nature (Hochschild Citation2016). His transgressive racism accomplishes numerous political objectives, including dehumanizing his targets, consolidating his power, eroding democratic norms, and distracting from policy and legal changes.

The spectacle of Trump’s racism—the incessant tweets, outrageous statements, and dehumanizing immigration policies—cannot be divorced from his neoliberal environmental agenda. Indeed, a growing number of scholars have shown how deep historicization is necessary to understand how racism informs contemporary economic structures and processes (Wilson Citation2000; Gilmore Citation2002; Baptist Citation2016; Woods Citation2017). Recently, Inwood (Citation2018) argued that whiteness, which is a form of white supremacy, is a powerful “counter-revolutionary” force that “impede[s] progressive and racial reconfigurations of the US racial state” (3). This is an important move that foregrounds the deeply problematic nature of whiteness itself, as it readily slips into white nationalism and other forms of white supremacy. One reason that whiteness impedes progressive change, including environmentalism, is because it is, by definition, antidemocratic, as it seeks to exclude and subordinate. Never in U.S. history has mobilizing along whiteness led to greater democracy and equality. Indeed, its opposite—the black radical tradition (BRT)—consistently leans toward greater freedom and inclusion (Robinson Citation2000). The BRT refers to the centuries-long struggle of black people to resist racial capitalism, a system that “not only extracts life from black bodies, but dehumanizes all workers while colonizing indigenous lands and incarcerating surplus bodies” (G. T. Johnson and Lubin Citation2017, 12). The BRT, which is not limited to black people, includes abolition geographies (Gilmore Citation2017) and abolition ecologies (Heynen Citation2016) and is generally associated with progressive change.

Inwood (Citation2015) noted a second problem with whiteness: its usage as a “racial fix.” Similar to a spatial fix, racial fixes are employed to resolve a crisis, however temporarily. In the United States, crises are routinely resolved by deploying racism to either blame people of color or otherwise appeal to the white nation (Hochschild Citation2016). Solving crises through preexisting relations, including racism, is fundamental to U.S. politics (Gilmore Citation1999; Woods Citation2017).

We see both dynamics occurring in the Trump era. Trump employs a racial fix by blaming racial others and immigrants to offer the white nation a psychological wage (Du Bois Citation2014). This wage does not merely validate white people’s superiority; rather, it addresses their emotional dislocation, fear, and resentment of a changing world (Hochschild Citation2016), affirming their status as the true nation (Thobani Citation2007). Clearly, this works against progressive change by aligning the white working class with capital (Du Bois Citation2014), but it also has implications for environmental governance (Hochschild Citation2016).

The current wave of white supremacy has been brewing for decades as Republicans attracted southern whites through racial resentment (Hajnal and Rivera Citation2014; Inwood Citation2015; Tesler Citation2016; Woods Citation2017). The election of Barack Obama, growing economic precarity, changing demographics, and multiculturalism all contributed to a deep resentment on the part of many whites, which candidate Trump tapped into.

If a nation is an “imagined political community” (Anderson Citation1983), the U.S. white nation is a political community constituted by whiteness and Christianity. It is not defined by the exclusion of non-whites and non-Christians but rather by the valorization of whiteness and Christianity. Not only does it equate white Christianity with the essence of the U.S. nation, but it considers it superior to those others deemed threats or intruders.Footnote1 Moreton-Robinson (Citation2016) argued that white nationalism in settler societies is largely defined by entitlement and possession, especially in terms of territory and state (see also Harris Citation1993). Although whiteness has varied geographically in the United States (Vanderbeck Citation2006; see also C. Johnson and Coleman Citation2012), contemporary white nationalism has been consolidated and strengthened through populism and white supremacy (Inwood Citation2015), although it might contain diverse racist ideologies.

By nurturing the white nation via spectacular racism, Trump has shifted the racial formation so that overt white supremacy is increasingly normalized (Page and Dittmer Citation2018). This, in turn, paves the way for dehumanizing policy. For instance, when he declared that there “were fine people on both sides” (“Full Transcript and Video” Citation2017), after the 2017 Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Trump legitimized white supremacist violence, thereby normalizing it. Such acts contribute to a climate in which Latinx children were separated from their parents at the U.S.–Mexico border, as happened in 2018. Such rhetoric and actions not only nurture and embolden the white nation, but they dehumanize racial others: They are not worthy of full legal and moral consideration. Indeed, they are arguably mere pawns in Trump’s political machinations.

Another important shift in the racial formation is spectacular racism’s ability to deflect attention away from political and economic crises. This is especially significant early in new regimes, when accepted norms are being violated and spectacular racism devours both media attention and individual energy. Relatedly, because the white nation is being nurtured, the possibility of structural critique is foreclosed. Instead, the white nation is offered false explanations, further dividing the working class. At the time of this writing, for example, during midterm elections, Trump hoped to send 15,000 troops to the southern U.S. border to block Central American immigrants, who he has demonized and blames for U.S. problems (Gonzales Citation2018).

Spectacular racism fuels and coexists with other manifestations of racism, including institutional racism and white privilege (Pulido Citation2000). It functions to enhance authoritarian and populist power by solidifying and empowering a political base that is partially animated by white supremacy and xenophobia (Zeskind Citation2012; McElwee and McDaniel Citation2017). It generates loyalty to an individual, rather than to political ideas or institutions (Frum Citation2017; see also Taub Citation2016). Spectacular racism, white nationalism, and authoritarianism are all distinct but work together in the Trump era. Portions of the U.S. electorate have always supported authoritarian figures (Hetherington and Suhay Citation2011; MacWilliams Citation2016; Koch Citation2017), who offer easy solutions to insecurity and change (Taub Citation2016). They rise to power through elections by aligning themselves with establishment politics and appealing to the public (Levitsky and Ziblatt Citation2018). Although certainly not Trump’s only means of attracting support, spectacular racism has been central to his strategy. Trump’s calculated use of spectacular racism has channeled diffuse anger and anxiety into a ferocious wave that is the white nation. Thus, the white nation is foundational to Trump’s power. Despite violating social norms, disregarding laws, and maintaining a chaotic administration, Trump has retained a loyal base (Graham Citation2017). Trump has successfully reshaped the Republican Party (Malone, Enten, and Nield Citation2016; Isenstadt Citation2017; Thompson 2018), so that it no longer even espouses racial equality (Page and Dittmer Citation2018). Trump understands the power of his base and seeks to nurture it, as it allows him to continue to function as an authoritarian. The white nation is the fulcrum that enables Trump’s agenda, which clearly favors elites and capital.

Method

Data were collected via a class-based research project at the University of Oregon in the winter of 2018.Footnote2 Students were divided into teams focused on environmental and racial issues. Environmental teams studied water, land, climate, air, toxins, and environmental justice, and the racial teams studied black people, Indigenous people, Jews and Palestinians, Mexicans and Latinxs, South Asians, Muslims and Arabs, whites, China, and the Koreas. Each group sought to find all events related to their topic that emanated from the Trump administration, federal legislature, and judiciary between 20 January 2017 and 20 January 2018. Initially, we drew from extant lists, such as Columbia and Harvard law schools’ environmental trackers and the American Civil Liberties Union’s lists, and then we branched out. We followed news leads, the Congressional Record, the White House’s Presidential Actions, and the like.

As shows, an event could be rhetoric, a policy, or anything in between. Specifically, an event was defined as new policy, policy changes, policy delays, observed acts of censorship, executive actions, appointments (including nonappointments), budgets, court rulings, tweets, and speeches.

Table 1. Delineation of events, action, and discourse

We included all legislative action, including proposed bills. We included all tweets from Trump, as the Department of Justice views them as official presidential statements, as well as tweets from then-Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Director Scott Pruitt. We struggled to decide which racial groups to study and how to categorize them. This became especially difficult in terms of groups that clearly transcend the domestic racial formation, such as Koreans. Ultimately, we included as many identifiable groups as possible. Events that are both racial and environmental, including the Presidential Memorandum Regarding Construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline, appear on both lists.

We acknowledge the fictitious nature of our categories. Indeed, environmental justice scholars have advocated for collapsing such boundaries to understand how environmental injustice is produced (Pulido Citation2000, Citation2016). Our objective, however, is to document state actions. Although it is true that universal environmental regulations have uneven consequences, only rarely is the current federal government connecting racism and environmental governance (Holifield Citation2012; Newkirk Citation2018). Recall that under neoliberal multiculturalism the state has “dematerialized” race, and whereas previous administrations were invested in contracting the conception of racism, the Trump administration is committed to disavowing its existence. Thus, with a few exceptions, such as the poisoned water of Flint, Michigan, pesticide deregulation, and public lands involving Indigenous people, the state treats race and the environment as separate spheres.

For each event we noted the date, responsible entity, publicity level, kind (e.g., judiciary vs. budget), justification, push-back (if any), and potential impacts across space and time. We reviewed the data, addressed duplication, and analyzed it according to the patterns and themes detailed in the tables included here. The data set is available at www.laurapulido.org.

Spectacular Racism and Environmental Deregulation in the Trump Era

The data indicate that Trump’s environmental and racial agendas have unfolded in distinct fashions, which we believe are meaningful. Despite significant chaos, we view Trump as a strategist and environmental deregulation as part of a larger neoliberal agenda embraced by the Republican Party. This is important because agendas that fully align with the GOP have been more successfully implemented than those that do not. It is important to recall that Republican opposition to Trump existed early on, although it has since vanished (Jacobson Citation2017; Chait Citation2018). Thus, these data capture a more fractious GOP—one that fully supported environmental rollbacks but had some unease with racism. Given these dynamics, it is not surprising that spectacular racism has helped obscure the relatively smooth and devastating deregulation. This obscuring has occurred through numbers and “noise.”

Numbers

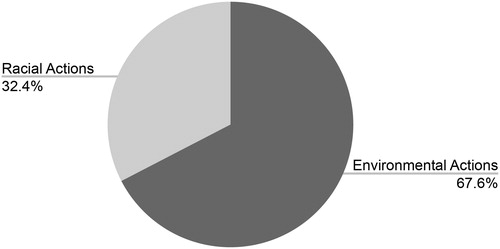

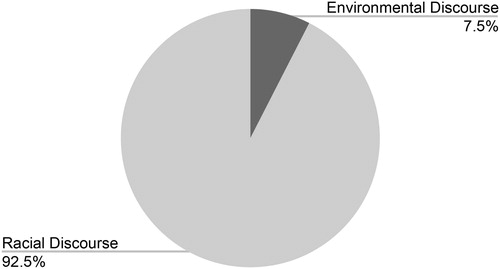

Numbers refers to the frequency of events. We found 195 environmental and 354 racial events (). A first glance suggests that more resources were invested in racial rather than environmental events. There is an important distinction, however, between types of events: concrete actions versus rhetoric. Specifically, we found that concrete actions were more likely to be environmentally related, whereas rhetoric was more likely to be racist. These differences are further illuminated in and .

Table 2. Frequency and kind of environmental and racial events: 20 January 2017 to 20 January 2018

Figure 1. All actions during the first year of Trump’s presidency (N = 256) broken into environmental and racial arenas.

Figure 2. All discursive events during the first year of Trump’s presidency (N = 293) broken into environmental and racial arenas.

Table 3. Mechanisms for environmental events: 20 January 2017 to 20 January 2018

indicates that 68 percent of all concrete actions were environmentally related, compared to 32 percent that were racial. This divergence is even more pronounced in , which shows that 92.5 percent of all discursive events were racial, whereas only 7.5 percent were environmental. Closer inspection of the environmental actions is revealing. lists the range of environmental events. Topping the list are policy, appointments, and executive actions. These three categories account for almost 70 percent of all events and embody a broad neoliberal agenda. Policy actions included rollbacks from the Obama era, the Department of Interior’s (DOI) “streamlining” of National Environmental Policy Act reviews, and reconsidering fuel economy standards. As many have documented, the easing of regulatory requirements is central to neoliberalism (Holifield Citation2004; Heynen, McCarthy, and Robbins Citation2007; Faber Citation2008; Himley Citation2008; Castree Citation2010). We were also interested in how deregulation was narrated, so we analyzed the justifications offered. The Trump administration was quite frank in justifying its actions. lists explanations given by the responsible party.

Table 4. Justifications for environmental events: 20 January 2017 to 20 January 2018

Significantly, there was no explanation for almost one third of all environmental actions. This silence registers as an absence of noise, which we explore later. The next two categories, which total just over 40 percent, are business interests or competitiveness and efficiency. Although it is sometimes necessary to decipher coded language, this is not the case. We believe that the justifications accurately reflect the Republican Party’s stated priorities. Efficiency justified 20 percent of all environmental actions. Here, efficiency is an effort to make the regulatory state leaner and more agile. Efficiency portends to save taxpayers money and make regulation less burdensome for industry, but efficiency also embodies what Peck (Citation2001, 447) called the “hollowing-out” of regulatory capacity. This was exemplified by thirty environmental nonappointments.

Appointments serve multiple purposes. Some, like Ben Carson, are random choices for departments that are not priorities. Others are carefully chosen for their experience in undermining regulatory agencies, such as the appointment of Nancy Beck to the EPA’s toxic chemicals unit. Beck came from the American Chemistry Council, where she made tracking toxins more difficult. In a major sweep, Pruitt barred scientists who received EPA grants from serving on the agency’s advisory boards (Cornwall Citation2017). He justified his actions as creating a level playing field for industry. Indeed, between 2017 and 2018 the percentage of private consultants and industry scientists grew from 7 percent to 32 percent (Gustin Citation2018). These are textbook examples of the “polluter-industrial complex,” which includes polluters capturing regulatory agencies (Faber Citation2008).

A third form of neoliberal governance is privatization and creating opportunities for industry. This was most pronounced in terms of fossil fuels. One of the first things Trump did was issue a Presidential Memorandum supporting the Keystone XL and Dakota Access pipelines. This was followed by expanding offshore drilling (Department of Interior Secretarial Order 3354 Citation2017), and reviewing national monuments. The breadth, depth, and speed of environmental deregulation suggests that—unlike other parts of the Trump agenda, such as the Muslim ban, which was characterized by chaos and massive opposition—this wave has been relatively smooth and carefully crafted. One reason for this is because environmental governance has been envisioned as a sequential process. Consider that in February 2017 Pruitt was appointed EPA director. On 28 March Trump signed the Presidential Executive Order on Promoting Energy Independence and Economic Growth. On 29 March the DOI lifted the ban on coal mining. The administration explained, “Given the critical importance of the Federal coal leasing program to energy security, job creation, and proper conservation stewardship, this Order directs efforts to enhance and improve the Federal coal leasing program” (Secretary of the Interior, Order No. Citation3348). These events should be seen as linked. Despite having to resign over ethics violations, Pruitt was a skilled administrator who previously sued the EPA numerous times. Unlike other Trump appointees, he understood the regulatory bureaucracy and set to work.

Executive actions are also part of this sequencing. They provide a different but complementary way to enact policy, which is essentially circular: Executive actions drove agency agendas; Pruitt implemented changes, which were then justified by executive actions.

Returning to and the justifications for environmental events, we see that business interests, efficiency, and national security comprised almost 50 percent of the total. These are core values codified in early executive orders. Hence, when the EPA limited power plants’ toxic metal emissions in April 2017, the justification was that it was an “inordinate cost to industry.”

The administration’s environmental deregulation has been so exceptionally fast and smooth that it suggests some level of preplanning. Like the Federalist Society, which vetted judicial nominees for Trump (Savage Citation2017), conservative organizations like the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) have served a similar function (Center for Media and Democracy Citation2018). ALEC has written probusiness legislation intended to proliferate and eventually reach the federal level. Although we do not claim that ALEC influenced the Trump administration, we assume that something comparable was at work.

In contrast, there were far fewer concrete racist actions than environmental ones. indicates that less than 25 percent of all racial events were actions. Although there were many more racial events (354) than environmental ones (195), there were still ninety more environmental actions than racial ones. Of course, numbers do not indicate impact. The Muslim ban, for instance, has profoundly affected peoples’ lives, as has the narrowing of asylum claims. It bears repeating: Racist rhetoric creates the conditions for extraordinary dehumanization and should never be dismissed.

Racial actions include seeking to dismantle the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) legislation, building a southern U.S. border wall, not responding to a Congressional Black Caucus letter, and banning Muslims. Such efforts are intended to both insult or harm particular groups, while affirming the white nation. Likewise, the appointment of a disproportionate number of white men actively signals to whites that they are rightful owners of the nation (Hochschild Citation2016). Such appointments, given their conservative orientation, are then likely to prioritize the interests of the white nation and capital.

Other efforts seek to “exalt” the white nation (Thobani Citation2007). Trump withdrew funding for Life After Hate, an organization offering alternatives to white supremacy and redirected $400,000 toward fighting anti-Islamic extremism. Similarly, the Global War on Terrorism Memorial Act was passed while the National Park Service cut $98,000 for a project honoring the Black Panther Party. These actions exemplify Trump’s refusal to criticize white supremacist violence while honoring the white nation. These actions must be seen as relational—there is no white nation without racial and colonized others.

Noise

Noise highlights the attention associated with specific events. Let us return to , which shows all discursive events. The fact that environmental issues comprised less than 10 percent of all discursive events indicates that the Trump regime was more likely to be silent on environmental issues and relatively “noisy” on racial ones. With some exceptions, such as the Paris Accord, pipelines, and national monuments, most environmental actions have been unfolding in silence. As one student observed, “Trump is not tweeting about air.” These silences are meaningful, especially in light of the number of environmental actions. When Trump does make environmental noise, such as his tweet in November 2017, it is symbolic: “It is finally happening for our great clean coal miners!”

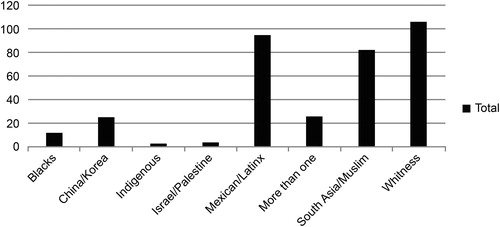

We categorized racist rhetoric by all discursive events and by tweets alone. On Twitter, whites were the most frequently referenced group (). Despite Trump’s attempt to equate the protesters in Charlottesville’s Unite the Right Rally, most white-directed comments were subtle. The vast majority were references to “Make America Great Again,” which we interpreted as hailing the white nation (Ngo Citation2017; Weems Citation2017).

Figure 3. All racial tweets during the first year of Trump’s presidency (N = 355) broken down by racial group.

details how racist rhetoric was distributed by group. Mexicans and Latinxs led the way with ninety-four racist comments. This rhetoric was extremely noisy, as seen in the tweet data in . Recall that Trump initiated his campaign with transgressive remarks about Mexicans and the 2018 midterm elections were marked by the vilification of Central Americans. Although these events lie outside the data set, they provide important context. Despite most of Trump’s comments targeting immigrants, it is impossible to conceive of Mexico and Mexican immigrants outside of the U.S. racial formation. As Rivera (Citation2006) argued, Mexico has served as a racial and national other to the United States since the Mexican–American War, contributing to Mexicans being ideal fodder for Trump’s spectacular racism. Because of the deep U.S. history of anti-Mexican racism, pejorative meanings are well established and pervasive. One need not “produce” new meanings or connections—one can simply draw on hegemonic anti-Mexican ideology and sentiment. Although Trump attacked Mexico and Mexican-Americans, he reserved most of his bile for immigrants, most of whom cannot vote. Indeed, Mexican immigrants are complex racial subjects, as they are seen as posing racial and national threats to the white nation (Huntington Citation2004; Chávez Citation2008).

Table 5. Number of discursive events by group: 20 January 2017 to 20 January 2018

Next is the category of Muslims, South Asians, and Arabs, with eighty-seven discursive events. As a transnational population, the rhetoric is less directed against any state but rather at multiple peoples connected by region and religion. This diasporic population is at least partly targeted precisely because of their presence in and connection to the United States. For example, in February 2017 Trump tweeted: “Everybody is arguing whether or not it is a BAN. Call it what you want, it is about keeping bad people (with bad intentions) out of country!” People and regions related to Islam have been positioned as others to the West and the United States for centuries but especially after 11 September 2001 (Said Citation2004). Similar to anti-Mexican discourse, anti-Islam rhetoric has deep roots in the United States, but its spectacular nature combined with specific actions, such as the Muslim ban, are profoundly reshaping the racial formation.

Significantly, black people and Native Americans were targeted far less. We used the term black people to describe Trump’s racism because although most remarks refer to African Americans, some were aimed at black people in Africa and the Caribbean. We saw these as distinct from other international groupings because they were rarely directed toward another country but rather black people per se. Further, such racist rhetoric reflects a global blackness that is universally subordinate (Sharpe Citation2016). We were initially surprised by the relatively low levels of antiblack racism but attributed this to two things.Footnote3 First, African Americans, despite their secondary status, are more accepted as part of the U.S. nation in that their racialization is not tied to an immigrant status. To be clear, black people are certainly not part of the white nation, but nationalism is a driving force behind Trump’s racism. Many Americans recognize, however begrudgingly, that African Americans are part of U.S. history through slavery, even if they refuse to acknowledge its afterlife that shapes contemporary black experiences (Hartman Citation2008; Sharpe Citation2016).

Black peoples’ position as the ultimate racial other within the U.S. racial formation might also influence their treatment by Trump. Because they are considered the leaders of the civil rights movement and have influenced how the United States frames race, African Americans serve as a litmus test for what constitutes racism. Thus, whereas it has been acceptable to vilify Mexicans and Muslims, it is more transgressive to attack African Americans. Indeed, Trump has a long history of antiblack racism, but he limited his explicit antiblack rhetoric during his first year in office. Nonetheless, there were numerous law-and-order comments directed against groups like Black Lives Matter and “Twitter wars” with black athletes protesting police killings.

Native Americans, who were also infrequently targeted by racist rhetoric, occupy a distinct position as colonized people. Although black and Indigenous people encountered less racist rhetoric from Trump, they have not been without harm. For Indigenous people, we view environmental actions themselves as violence against colonized people, as it is their land that is being appropriated and degraded, with vast consequences for their health, cultures, nations, and ability to survive. Although it can be argued that both Native and black people are part of the nation, we must recall that the United States was forged through slavery and colonization. Thus, their exclusion, domination, and eradication were central to the formation of the United States (Harris Citation1993; Smith Citation2012). The fact that Mexicans and Latinx and Muslims and Arabs are currently more targeted by Trump’s racism reflects the complexity and fluidity of the U.S. racial formation (Bonilla-Silva Citation2004). Alternatively, attacking Latinxs might prepare the path for more concentrated assaults on black people.

Multiple racial groups were also targeted simultaneously, at a frequency comparable to that of black and Native people. In July Trump tweeted, “At some point the Fake News will be forced to discuss our great jobs numbers, strong economy, success with ISIS, the border & so much else!” Here, he brings together ISIS (Islam) and the border (Mexicans), while emphasizing national security and affirming the white Christian nation.

Although we have distinguished between rhetoric and actions, we are cognizant of how the two inform each other. Consider Trump’s proposed border wall. Clearly, the wall maintains the borders of the white nation both metaphorically and literally. It nurtures Trump’s base, thereby securing continued support. Repeated reference to the border wall has also pushed the realm of political possibility to the right. In the winter of 2018 the fate of unaccompanied minors, DACA recipients, was held hostage to Trump’s desire for the wall. Finally, such tactics, both spectacular racism and using DACA recipients as bargaining chips, further erode the norms and humanity that are essential to a functioning democracy. As such, Trump’s relentless racist rhetoric normalizes a spectacularly racist policy agenda and obscures vast environmental deregulation.

Concluding Thoughts

We have explored the patterns between racist and environmental events during the Trump administration’s first year. During this period, environmental issues were far more likely to be concrete actions, whereas racism was more likely to be rhetorical. Accordingly, we suggest that spectacular racism, regardless of intent, obscures environmental deregulation.

Perhaps more significant are the larger implications for the racial formation and environmental governance, which we can only gesture to. The ascent of the white nation contributes to the abandonment of neoliberal multiculturalism and environmental protections, as capital and whiteness are protected. This raises several questions regarding the relationship between the two, including why millions of the white working class would vote against their material interests. Such a question assumes, of course, that voters are rationale beings, when, in fact, the evidence suggests that people supported Trump for emotional reasons (Hochschild Citation2016; Koch Citation2018), whether fear, anger, or hope.

If much of the vote was emotionally driven, is environmental deregulation simply collateral damage? Hochschild (Citation2016), in her study of Louisiana Tea Party members, examined the relationship between conservative voters and environmental regulation and painted a more complex picture. She identified two reasons why whites resented the government, even amidst severe pollution. First, whites were deeply resentful because they felt displaced by racial others who had “cut in line,” through affirmative action, equal rights, and immigration, and, second, they did not believe that regulations served them (Hochschild Citation2016, 137). Instead, they believed that regulators targeted small businesses and individuals, which could not readily afford compliance, whereas big corporations were free to pollute. It is true that larger polluters are lightly regulated (Pellow Citation2004; Sze Citation2006; Faber Citation2008; Pulido, Kohl, and Cotton Citation2016; Dillon Citation2018), but Trump argued that deregulation would “Make America Great Again.” Hence, deregulation became a tool to build both the white nation and economic prosperity. Here, economic populism resonated and intersected with the grievances of the white nation.

Both our data and Hochschild’s (2016) findings seem to affirm Inwood’s (Citation2018) contention that white supremacy impedes progressive change—albeit at two different scales—the national and the local. Clearly, more research is necessary to clarify these dynamics. What is evident, however, is that overt white supremacy can never be isolated from other spheres of society, including seemingly unrelated ones. Its regressive nature can only be challenged by drawing on such formations as the BRT (Robinson Citation2000), of which the environmental justice, antiracist, and even mainstream environmental movements are a part.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the research assistance of Cristina Zepeda-Yanez and Aakash Upraity. Versions of this article were presented at the University of Uppsala and Willamette University, where we received very helpful feedback. We alone remain responsible for all shortcomings.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Laura Pulido

LAURA PULIDO is Professor of Ethnic Studies and Geography at the University of Oregon, Eugene, OR 97403. E-mail: [email protected]. Her research interests include race, comparative ethnic studies, environmental justice, and critical human geography.

Tianna Bruno

TIANNA BRUNO is a Doctoral Student in the Geography Department at the University of Oregon, Eugene, OR 97403. E-mail: [email protected]. Her research interests include critical environmental justice, black geographies, political ecology, and critical physical geography.

Cristina Faiver-Serna

CRISTINA FAIVER-SERNA is a Doctoral Candidate in the Geography Department at the University of Oregon, Eugene, OR 97403. E-mail: [email protected]. Her research interests include critical environmental studies, critical race studies, science and technology studies, Latinx geographies, and women of color feminist theory and praxis.

Cassandra Galentine

CASSANDRA GALENTINE is a Doctoral Student in the English Department at the University of Oregon, Eugene, OR 97403. E-mail: [email protected]. Her research interests include working-class literature, critical environmental justice studies, and new materialism.

Notes

1 For different articulations of the white nation, see Belew (Citation2018).

2 The students were Tianna Bruno, Bob Craven, Fiona de los Rios-McCucheon, Shiloh Deitz, Cristina Faiver-Serna, Lisa Fink, Cassandra Galentine, Theodore Godfrey, Ben Hinde, Nick Machuca, Katya Reyna, Derek Robinson, Kate Shields, Michael Skaja, Aakash Upraity, Adriana Uscanga Castillo, Shianne Walker, Claire Williams, Olivia Wing, Sara Worl, Jordan Wyant, Cristina Zepeda-Yanez, Holly Moulton, and Natalie Mosman.

3 For evidence on the continued toll that racism takes on African Americans, see Levine et al. (Citation2001), Phelan and Link (Citation2015), and Cunningham et al. (Citation2017).

References

- Anderson, B. 1983. Imagined communities: Reflections on the origins and spread of nationalism. London: Verso.

- Baptist, E. E. 2016. The half has never been told: Slavery and the making of American capitalism. New York: Basic Books.

- Belew, K. 2018. Bring the war home: The white power movement and paramilitary America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Bonds, A., and J. Inwood. 2016. Beyond white privilege: Geographies of white supremacy and settler colonialism. Progress in Human Geography 40 (6):715–33. doi:10.1177/0309132515613166.

- Bonilla-Silva, E. 2004. From bi-racial to tri-racial: Towards a new system of racial stratification in the USA. Ethnic and Racial Studies 27 (6):931–50. doi:10.1080/0141987042000268530.

- Castree, N. 2010. Neoliberalism and the biophysical environment 1: What “neoliberalism” is, and what difference nature makes to it. Geography Compass 4 (12):1726–33. doi:10.3167/ares2010010102.

- Center for Media and Democracy. 2018. ALEC exposed. Accessed July 20, 2018. http://www.alecexposed.org/wiki/ALEC_Exposed.

- Chait, J. 2018. The anti-Trump right has become Trump’s base. New York Magazine, July 3. Accessed July 18, 2018. http://nymag.com/intelligencer/2018/07/anti-trump-conservatives-have-become-trumps-base.html/gtm=top>m=bottom.

- Chávez, L. 2008. The Latino threat. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Cornwall, W. 2017. Trump’s EPA has blocked agency grantees from serving on science advisory panels. Here is what it means. Science, October 31. Accessed March 30, 2018. http://www.sciencemag.org/news/2017/10/trump-s-epa-has-blocked-agency-grantees-serving-science-advisory-panels-here-what-it.

- Cunningham, T. J., J. B. Croft, Y. Liu, H. Lu, P. I. Eke, and W. H. Giles. 2017. Vital signs: Racial disparities in age-specific mortality among blacks or African Americans—United States, 1999–2015. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 66 (17):444–56. doi:10.1558/5mmwrmm6617e1.

- Department of Interior. 2017. Supporting and improving the federal onshore oil and gas leasing program and federal solid mineral leasing program. Secretarial Order 3354. July 6. Accessed July 18, 2018. https://www.doi.gov/sites/doi.gov/files/uploads/doi-so-3354.pdf.

- Dillon, L. 2018. The breathers of Bayview Hill: Redevelopment and environmental justice in southeast San Francisco. Hastings Environmental Law Journal 24 (2):227–36.

- Du Bois, W. E. B. 2014. [2014]. Black reconstruction in America. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Faber, D. 2008. Capitalizing on environmental injustice: The polluter-industrial complex in the age of globalization. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Frum, D. 2017. How to build an autocracy. The Atlantic, January 30. Accessed March 20, 2018. https://www.theatlantic.com/press-releases/archive/2017/01/how-to-build-an-autocracy-the-atlantics-march-cover-story-online-now/515115/.

- Full transcript and video: Trump’s news conference in New York. 2017. New York Times, August 15. Accessed February 3, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/15/us/politics/trump-press-conference-transcript.html/action=click&module=RelatedCoverage&pgtype=Article®ion=Footer

- Gilmore, R. W. 1999. Globalisation and U.S. prison growth: From military Keynesianism to post-Keynesian militarism. Race & Class 40 (2–3):171–88. doi:10.1177/030639689904000212.

- Gilmore, R. W. 2002. Fatal couplings of power and difference: Notes on racism and geography. The Professional Geographer 54 (1):15–24.

- Gilmore, R. W. 2017. Abolition geography and the problem of innocence. In Futures of black radicalism, ed. T. G. Johnson and A. Lubin, 225–40. New York: Verso.

- Gokariksel, B., and S. Smith. 2018. Tiny hands, tiki torches: Embodied white male supremacy and its politics of exclusion. Political Geography 62:209–11. doi:10.1016/polgeo201710010.

- Gonzales, R. 2018. Trump says he’ll send as many as 15,000 troops to the southern border. National Public Radio, November 1. Accessed November 5, 2018. http://www.npr.org/2018/10/31/662735242/trump-says-hell-send-as-many-as-15-000-troops-to-the-southern-border.

- Graham, D. 2017. Trump’s shrinking, energized base. The Atlantic, September 8. Accessed March 30, 2018. https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2017/09/trumps-shrinking-impassioned-base/539160/.

- Gustin, G. 2018. Trump administration deserts science advisory boards across agencies. Inside Climate News, January 18. Accessed November 6, 2018. https://insideclimatenews.org/news/18012018/science-climate-change-advisory-board-epa-interior-trump-administration.

- Hajnal, Z., and M. U. Rivera. 2014. Immigration, Latinos, and white partisan politics: The new democratic defection. American Journal of Political Science 58 (4):773–89. doi:10.1111/ajps12101.

- Harris, C. 1993. Whiteness as property. Harvard Law Review 106 (8):1710–91.

- Hartman, S. 2008. Lose your mother: A journey along the Atlantic slave route. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Hetherington, M., and E. Suhay. 2011. Authoritarianism, threat, and Americans’ support for the war on terror. American Journal of Political Science 55 (3):546–60. doi:10.1111/15405907201100514.

- Heynen, N. 2016. Urban political ecology II: The abolitionist century. Progress in Human Geography 40 (6):839–45. doi:10.1177/0309132515617394.

- Heynen, N., J. McCarthy, and P. Robbins. 2007. Neoliberal environments: False promises and unnatural consequences. London and New York: Routledge.

- Himley, M. 2008. Geographies of environmental governance: The nexus of nature and neoliberalism. Geography Compass 2 (2):433–51. doi:10.1111/17498198200800094.

- Hochschild, A. 2016. Strangers in their own land. New York: New Press.

- Holifield, R. 2004. Neoliberalism and environmental justice in the United States Environmental Protection Agency: Translating policy into managerial practice in hazardous waste remediation. Geoforum 35 (3):285–97. doi:10.1016/geoforum200311003.

- Holifield, R. 2012. Environmental justice as recognition and participation in risk assessment: Negotiating and translating health risk at a superfund site in Indian country. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 102 (3):591–613. doi:10.1080/000456082011641892.

- Huntington, S. 2004. Who are we? The challenges to America's national identity. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Inwood, J. 2015. Neoliberal racism: The “Southern strategy” and expanding geographies of white supremacy. Social & Cultural Geography 16 (4):407–23. doi:10.1080/146493652014994670.

- Inwood, J. 2018. White supremacy, white counter-revolutionary politics, and the rise of Donald Trump. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space. Advance online publication. doi:10.1177/2399654418789949.

- Inwood, J., and A. Bonds. 2016. Confronting white supremacy and a militaristic pedagogy in the U.S. settler colonial state. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 106 (3):521–29. doi:10.1080/2469445220161145510.

- Isenstadt, A. 2017. Trump purges enemies and reshapes party in his image. Politico, October 24. Accessed March 30, 2018. https://www.politico.com/story/2017/10/24/trump-republicans-corker-flake-purge-244139.

- Jacobson, G. C. 2017. The triumph of polarized partisanship in 2016: Donald Trump’s improbable victory. Political Science Quarterly 132 (1):9–41. doi:10.1002/polq12572.

- Johnson, C., and A. Coleman. 2012. The internal other: Exploring the dialectical relationship between religious exclusion and the construction of national identity. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 102 (4):863–80. doi:10.1080/000456082011602934.

- Johnson, G. T., and A. Lubin. 2017. Introduction. In Futures of black radicalism, ed. G. T. Johnson and A. Lubin, 9–18. London: Verso.

- Kobayashi, A., and L. Peake. 2000. Racism out of place: Thoughts on whiteness and an antiracist geography in the new millennium. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 90 (2):392–403. doi:10.1111/0004560800202.

- Koch, N. 2017. Orientalizing authoritarianism: Narrating U.S. exceptionalism in popular reactions to the Trump election and presidency. Political Geography 58:145–47. doi:10.1016/polgeo201703001.

- Koch, N. 2018. Trump one year later: Three myths of liberalism exposed. Political Geography 62:212–14. doi:10.1016/polgeo201710010.

- Levine R. S., J. E. Foster, R. E. Fullilove, M. T. Fullilove, N. C. Briggs, P. C. Hull, B. A. Husaini, and C. H. Hennekens. 2001. Black–white inequalities in mortality and life expectancy, 1933–1999. Implications for healthy people 2010. Public Health Reports 116 (5):474–83. doi:10.1093/phr/116.5.474

- Levitsky, S., and D. Ziblatt. 2018. How democracies die. New York: Crown.

- MacWilliams, M. C. 2016. Who decides when the party doesn’t? Authoritarian voters and the rise of Donald Trump. PS: Political Science & Politics 49 (4):716–21. doi:10.1017/S1049096516001463.

- Malone, C., H. Enten, and D. Nield. 2016. The end of a republican party. Accessed March 30, 2018. https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/the-end-of-a-republican-party/.

- McElwee, S., and J. McDaniel. 2017. Economic anxiety didn’t make people vote for Trump, racism did. The Nation, May 8. Accessed March 20, 2018. https://www.thenation.com/article/economic-anxiety-didnt-make-people-vote-trump-racism-did/.

- Melamed, J. 2011. Represent and destroy: Rationalizing violence in the new racial capitalism. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Moreton-Robinson, A. 2016. The white possessive: Property, power and indigenous sovereignty. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Newkirk, V. R., II. 2018. Trump’s EPA concludes environmental racism is real. The Atlantic, February 28. Accessed March 30, 2018. https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2018/02/the-trump-administration-finds-that-environmental-racism-is-real/554315/.

- Ngo, B. 2017. Immigrant education against the backdrop of “Make America great again.” Educational Studies 53 (5):429–32. doi:10.1080/00131946.2017.1355800.

- Nixon, R. 2011. Slow violence and the environmentalism of the poor. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Omi, M., and H. Winant. 1994. Racial formation in the United States: From the 1960s to the 1990s. London and New York: Routledge.

- Page, S., and J. Dittmer. 2018. Mea culpa. Political Geography 62:207–9. doi:10.1016/polgeo201710010.

- Peck, J. 2001. Neoliberalizing states: Thin policies/hard outcomes. Progress in Human Geography 25 (3):445–55.

- Pellow, D. N. 2004. Garbage wars: The struggle for environmental justice in Chicago. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Pellow, D. N. 2017. What is critical environmental justice? Cambridge, UK: Polity.

- Phelan J. C., and B. G. Link. 2015. Is racism a fundamental cause of inequalities in health? Annual Review of Sociology 41:311–30. doi:10.11146/annurev-soc-073014-112305.

- Pulido, L. 2000. Rethinking environmental racism: White privilege and urban development in Southern California. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 90 (1):12–40.

- Pulido, L. 2015. Geographies of race and ethnicity I: White supremacy vs. white privilege in environmental racism research. Progress in Human Geography 39 (6):809–17. doi:10.1177/0309132514563008.

- Pulido, L. 2016. Flint Michigan, environmental racism and racial capitalism. Capitalism Nature Socialism 27 (3):1–16. doi:10.1080/1045575220161213013.

- Pulido, L. 2017. Geographies of race and ethnicity II: Environmental racism, racial capitalism and state-sanctioned violence. Progress in Human Geography 41 (4):524–33. doi:10.1177/0309132516646495.

- Pulido, L. 2018. Geographies of race and ethnicity III: Settler colonialism and nonnative people of color. Progress in Human Geography 42 (2):309–18. doi:10.1177/0309132516686011.

- Pulido, L., E. Kohl, and N. Cotton. 2016. State regulation and environmental justice: The need for strategy reassessment. Capital Nature Socialism 27 (2):12–31. doi:10.1080/10455752.2016.1146782.

- Rivera, J. 2006. The emergence of Mexican America: Recovering stories of Mexican peoplehood in U.S. culture. New York: New York University Press.

- Robinson, C. J. 2000. Black Marxism: The making of the black radical tradition. 2nd ed. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Said, E. 2004. Orientalism once more. Development and Change 35 (5):869–79. doi:10.1111/14677660200400383.

- Savage, C. 2017. Trump is rapidly changing the judiciary. Here’s how. New York Times, November 11. Accessed March 30, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/11/11/us/politics/trump-judiciary-appeals-courts-conservatives.html.

- Schlosberg, D., and D. Carruthers. 2010. Indigenous struggles, environmental justice, and community capabilities. Global Environmental Politics 10 (4):12–35. doi:10.1162/GLEPa00029.

- Secretary of the Interior, Order No. 3348. Concerning the federal coal moratorium. Accessed February 3, 2019. https://www.doi.gov/sites/doi.gov/files/uploads/so_3348_coal_moratorium.pdf

- Sharpe, C. 2016. In the wake: On blackness and being. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Smith, A. 2012. Indigeneity, settler colonialism, White supremacy. In Racial formation in the twenty-first century, ed. D. Martinez Hosang, O. LaBennett, and L. Pulido, 66–90. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- Sze, J. 2006. Noxious New York: The racial politics of urban health and environmental justice. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Taub, A. 2016. The rise of American authoritarianism. Accessed March 30, 2018. https://www.vox.com/2016/3/1/11127424/trump-authoritarianism.

- Tesler, M. 2016. Post-racial or most racial? Race and politics in the Obama era. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Thobani, S. 2007. Exalted subjects. Toronto: University of Toronto.

- Thompson, D. 2018. Donald Trump’s language is reshaping American politics. The Atlantic, February 15. Accessed March 30, 2018. https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2018/02/donald-trumps-language-is-reshaping-american-politics/553349/.

- Vanderbeck, R. 2006. Vermont and the imaginative geographies of American whiteness. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 96 (3):641–59. doi:10.1111/14678306200600710.

- Weems, M. E. 2017. Make America great again? Qualitative Inquiry 23 (2):168–70. doi:10.1177/1077800416674752.

- Wilson, B. M. 2000. America's Johannesburg: Industrialization and racial transformation in Birmingham. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Woods, C. 2017. Development drowned and reborn, ed. L. Pulido and J. Camp. Athens: University of Georgia Press.

- Wright, M. 2015. Physics of blackness: Beyond the middle passage epistemology. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota.

- Yen-Kohl, E., and The Newtown Florist Club Writing Collective. 2016. “We’ve been studied to death, we ain’t gotten anything”: (Re) claiming environmental knowledge production through the praxis of writing collectives. Capitalism Nature Socialism 27 (1):52–67. doi:10.1080/1045575220151104705.

- Zeskind, L. 2012. A nation dispossessed: The Tea Party movement and race. Critical Sociology 38 (4):495–509. doi:10.1177/0896920511431852.