Abstract

Responding to calls for increased attention to actions and reactions “from above” within the extractive industry, we offer a decolonial critique of the ways in which corporate entities and multinational institutions draw on racialized rhetoric of “local” suffering, “local” consultation, and “local” culpability in oil as development. Such rhetoric functions to legitimize extractive intervention within a set of practices that we call localwashing. Drawing from a decade of research on and along the Chad–Cameroon Oil Pipeline, we show how multiscalar actors converged to assert knowledge of, responsibility for, and collaborations with “local” people within a racialized politics of scale. These corporate representations of the racialized “local” are coded through long-standing colonial tropes. We identify three interrelated and overlapping flexian elite rhetoric(s) and practices of racialized localwashing: (1) anguishing, (2) arrogating, and (3) admonishing. These elite representations of a racialized “local” reveal diversionary efforts “from above” to manage public opinion, displace blame for project failures, and domesticate dissent in a context of persistent scrutiny and criticism from international and regional advocates and activists. Key Words: coloniality, decolonial, elite, extraction, racism.

为了回应加强关注搾取产业 “由上而下” 的行动与反动之呼吁,我们对企业和跨国机构在石油产业中运用 “地方” 受苦、“地方” 谘询,以及 “地方” 罪责作为发展修辞的方式,提出去殖民的批判。此般修辞用来正当化在一系列我们称为 “洗刷地方” 的实践中的搾取性介入。我们运用在乍德—喀麦隆油管及其沿线历经十年的研究,展现多重尺度行动者如何在种族化的尺度政治中聚合,以声称对 “地方”人民的知识、责任与合作。这些企业对种族化的 “地方” 之再现,通过长期存在的殖民修辞进行编码。我们指认跨国政商关系绵密的菁英有关种族化的洗刷地方的三大相关且重叠的修辞与实践:(1)痛苦、(2)僭越、(3)劝告。这些对种族化的 “地方” 的菁英式再现,揭露了在受到国际与区域倡议者及社会运动者持续检视的脉络中,通过 “由上而下” 的分化来管理群众意见、转移计画失败的指责,以及驯化异议者的意图。关键词:殖民性,去殖民,菁英,搾取,种族主义。

Respondiendo a reclamos por la creciente atención a las acciones y reacciones que vienen “desde arriba” al interior de la industria extractiva, presentamos una crítica descolonial a la manera como las entidades corporativas y las instituciones multinacionales se apoyan en una retórica racializada del sufrimiento “local”, la consulta “local” y la culpabilidad “local” en el contexto de petróleo como desarrollo. Tal retórica funciona para legitimar la intervención extractiva dentro de un conjunto de prácticas que nosotros denominamos localwashing [“lavadolocal”]. Basándonos en una década de investigación sobre el Oleoducto Chad–Camerún, efectuada a lo largo del mismo, mostramos cómo actores multiescalares convergieron a reivindicar el conocimiento de la gente “local” y a asumir responsabilidad y colaboración con esta gente, dentro de políticas racializadas de escala. Estas representaciones corporativas de lo “local” racializado están codificadas a través de tropos coloniales de vieja data. Identificamos tres retóricas de la élite flexiana y prácticas de lavadolocal racializado, interrelacionadas y superpuestas: (1) angustiantes, (2) apropiantes, y (3) amonestantes. Estas representaciones elitistas de un “local” racializado revelan esfuerzos distractivos “de arriba” para manipular la opinión pública, desplazar la culpa de los fracasos en los proyectos y domesticar el disentimiento en un contexto de escrutinio y crítica persistentes de abogados y activistas internacionales y regionales. Palabras clave: colonialidad, descolonial, élite, extracción, racismo.

In 2013, Roger Leeds, the Director of the Center for International Business and Public Policy at Johns Hopkins and former international finance practitioner, argued that the Chad–Cameroon Oil Pipeline had been an “extraordinary opportunity for the World Bank. This is exactly what the World Bank was put on the earth to do: alleviate poverty, do capacity building, provide private sector approval.” Leeds (Citation2013) made the declaration at a seminar titled, “The Role of Public Policy in Private Sector Development,” which took place at University of Cape Town (UCT) in South Africa. Some forty audience members, mostly African consultants, policymakers, and academics working on the African continent, were gathered to deliberate on the particulars of this “oil as development” project. Oil as development is a shifting constellation of ideas grounded on the notion that oil extraction and production can and will initiate development and improve people’s well-being in extractive zones. The UCT seminar included a discussion of various aspects of the project’s eventual failure to deliver on the promises of oil as development—a failure that was publicly signaled by the World Bank’s ultimate withdrawal from the pipeline project in 2008 (which we sketch in detail later).

An hour and fifteen minutes into the seminar, Leeds took an informal poll of the audience. He asked, “How many people in the room, if employed by the Bank, would vote against the project?” Three people raised their hands against the project. The other thirty-seven or so people, even knowing that the project had been a “developmental failure,” would nonetheless vote to see the Chad–Cameroon Pipeline to fruition. The informal poll was suggestive of elite consensus and “expert” opinion on the economic policy framework set forth through the pipeline project, even following the public multi-institutional assessments, journalistic reports, and academic accounts of the project’s various and considerable failures. Organizations from the U.S. Institute of Peace to the international nongovernmental organization (NGO) Human Rights Watch called the reporting and monitoring structure of the Chad–Cameroon Pipeline a “model” for “corporate citizenship” (Shankleman Citation2006; Human Rights Watch Citation2015). Human Rights Watch (Citation2015) lauded the project as “important because it shows that the Bank is fully capable of responding more forcefully to similar problems than it does today, if only it possessed the commitment and the political will” (90). The latter plaudit was made even as the social welfare portion of the Chad–Cameroon Pipeline remained patently and publicly unfulfilled.

How do we explain this persistent faith in extractive projects as modernizing, even in the face of assiduous failures? Part of the explanation lies in the relentless optimism of profit-driven, often nationalistic, imaginaries and the anticipatory politics of corporate elite within the hydrocarbon industry (Kama Citation2013; Mason Citation2015; Weszkalnys Citation2015). Yet, the persistent will to extract is reflective of and dependent on more than those anticipatory effects generated and experienced in what Mason (Citation2015) referred to as the “events collectives” of oil elites. In part, as we aim to show, it is also because the hegemonic rhetoric of oil as development occurs within and is an embedded component of colonial and racist logics, designed and implemented by flexian elite, or border-crossing, like-minded individuals (Mosse and Lewis Citation2005; Wedel Citation2009). Optimistic and universal oil as development rhetoric “makes sense” when framed apolitically (Escobar Citation1995), ahistorically, and postracially (Daley Citation2013b).

In this article, we examine some of the key political contestations and elite rhetoric that legitimized the Chad–Cameroon Oil Pipeline as an oil as development project, both in the face of considerable antiextractive critique and, later, in the face of the project’s persistent failures. This historiography of the pipeline reveals some of the shifting corporate practices and rhetoric that we call racialized localwashing. International audiences perceive corporate localwashing as credible first and foremost because it occurs within a global scalar politics founded on pervasive antiblackness and the continued colonial subordination of African bodies and geographies. We draw from the literatures on race and coloniality, antiracist feminist politics of scale, and critiques of corporate entities to explicate the ways in which localwashing was refined, at least partially, in response to antiextractive critiques of the 1990s and early 2000s and in the context of rising postracial ideologies. We aim to explain the role of localwashing as a rhetorical racializing technique that structures dominant social narratives of oil as development in the central African countries of Cameroon and Chad through three shifting flexian elite practices and rhetoric(s): (1) anguishing and victimizing the “local”; (2) arrogating, claiming, and ventriloquizing the “local”; and, ultimately, (3) admonishing and blaming the “local” for the broken promises of oil as development. For the people living along the pipeline in Cameroon, the local as imagined through corporate descriptions remained chimerical. As we show, people lived largely at the peripheries of the project and its networks of power, at the same time that they critiqued its alienating power hierarchies and uneven practices. We conclude with reflections on the importance of a politically attuned decolonial geography of extraction that demystifies the racializations and antiblack racisms of corporate local-centric extraction.

Race, Coloniality, and Corporate Power

Race and Coloniality in Central Africa

Capitalism is racialized (Robinson Citation1983; Kelly Citation2000). Colonial-capitalist markets are “ordered by and through race [and] race [is] a mode of classifying, ordering, creating and destroying people, labour power, land, environment and capital” (Tilly and Shilliam Citation2017, 4). Race is a central organizing logic of the “coloniality of power” (or “coloniality”), which we understand to be the flexible and heterogeneous global structures of domination that perpetually reinscribe colonial hierarchies and divisions (Grosfoguel Citation2007; Ndlovu and Makoni Citation2014). Maldonado-Torres (Citation2007) wrote:

Coloniality … refers to long-standing patterns of power that emerged as a result of colonialism, but that define culture, labour, intersubjectivity relations, and knowledge production well beyond the strict limits of colonial administrations. (243)

Following formal decolonization, socioeconomic and environmental inequalities persisted through ecologically and social disruptive patterns of neo-extractivism and petro-politics together with the durability of the legal discursive framework of colonial dispossessions. Accumulation and extraction remain the dominant logics (Abourahme Citation2018; Yusoff Citation2018), enduring within the mentalities, socioeconomic, cultural, and knowledge structures and relations of the “postcolonial” era (Grosfoguel Citation2007; Maldonado-Torres Citation2007; Ndlovu-Gatsheni Citation2013).

Race, racialization, and racism are coconstitutive of what cultural theorists and sociologists Bacchetta, Maira, and Winant (Citation2019, 3) called “global raciality” within coloniality. Racialization refers to those material processes and rhetorical practices characterized by systematic refusals to recognize the equal humanity of nonwhite people (e.g., othering). Racialization reproduces a colonial hierarchy of humanness that both violently and unevenly structures and is structured by environments, political economies, and nature–society relations. Through racializing processes and their attendant racist rhetoric and ideas, bodies, lands, and knowledges are racially categorized, hierarchized, and situated within “global raciality” (Bacchetta, Maira, and Winant Citation2019). Illusions of “postraciality,” by which we mean the insistence on the irrelevance of race in supposed meritocratic societies, function to obscure or invisibilize racializing processes and rhetoric(s) as racist. Postraciality has become “an indispensable component of projects of ‘accumulation through dispossession’” because it is founded on a refusal to see or acknowledge the role and function of race and racialization within contemporary colonial capitalism (Bacchetta, Maira, and Winant Citation2019, 4).

The colonial matrix is characterized by “the inextricable combination of the rhetoric of modernity (progress, development, growth) and the logic of coloniality (poverty, misery, inequality)” (Bhambra Citation2014, 119). In this ordering, patriarchal whiteness and antiblackness are central in the material and symbolic establishments of corporate knowledge and authority, as well as the perpetuation of colonial difference. Indeed, “capitalism is actually dependent on anti-Blackness to realize itself” (Bledsoe and Wright Citation2019, 11).

In contemporary African societies, the racism of coloniality is evidenced in the persistent and often unspoken influences of antiblackness and white- and light-skinned dominance within corporate public façades. Corporate advertisements, rhetoric(s), practices, and policies are structured within and by the logics of racial coloniality and antiblackness. From celebrity campaigns in Sudan premised on racial hierarchies that position “Americans as ‘powerful saviours’ located at the top of the hierarchy of humanity” (Daley Citation2013b, 383; see also Mamdani Citation2009), to the deployment of scientific racism to legitimize black economic marginalization in South Africa (Ndlovu-Gatsheni Citation2013), to racially segregated labor regimes within multinational resource extraction in Equatorial Guinea (Appel Citation2012), racial hierarchies and racism are central to present-day corporate dominations and dispossessions across contemporary Africa. We seek to push these conversations farther by attending to the roles and functions of racism, racialization, and antiblackness on the African continent. Beyond the African diaspora and southern Africa, antiblackness and the roles of racial difference remain understudied (Pierre Citation2013b; Powell et al. Citation2017; Murrey Citation2018). Powell et al. (Citation2017) explained that

scholars of postcoloniality have been slow in applying a racial analysis to the contemporary study of Africa, despite [the] evidence of white privilege[,] questions of relevance to African realities, and of the racial underpinnings of global power hierarchies. (98)

Research in the social sciences on postcolonial central Africa has paid scarce attention to the role of race in general, including the role of whiteness and antiblackness in ordering contemporary political economies of extraction and dispossession. By expanding the purview of work in decolonial political geography, we hope to contribute to ongoing efforts to “unnaturalize” these omissions of race, racism, and racialization (Kobayashi and Peake Citation1994) from accounts of extractive intervention in a region (central Africa) that has also been peripheralized within the discipline of Anglophone geography.

Antiracist and Feminist Politics of Scale

Black feminist political geographer Daley (Citation2008) explained that the “dehumanization of the African has and continues to take place on a global, continental, regional, national and local scale” (232). She argued that it is only by “scaling up”—from the local authority who sanctions violence against the African, to the discrimination of the African by the state, to the indifference of the international community—that we can we see the networking of power that produces racialized dehumanizations (Daley Citation2008). Feminist geographies of scale help to explain the operations of racialization and practices of racism in contemporary colonial extraction.

Extraction occurs within the coloniality of power and often through the deployment of racial power in particular (Yusoff Citation2018). The racialized practice of framing extractive interventions by imagining spaces as “empty” of people (i.e., terra nullius) and nonproductive in capitalist terms have been closely chronologized and critiqued (Coronil Citation1997; Yusoff Citation2018). McKittrick (Citation2013) wrote of the ways in which black geographies are rhetorically vacuous and “emptied out of life” (7). Rex Tillerson, the former senior vice president of ExxonMobil, for example, described the implementation of the Chad–Cameroon Oil Pipeline in Chad: “We really had a blank page to start with. … And when you have a blank page, you have the opportunity to do some things differently” (quoted in Useem Citation2002, 102). The epistemological framing of antiblackness as absence (“a blank page”) acts as

a necessary precondition for the perpetuation of capitalism, as the perpetual expansion of capitalist practices requires “empty” spaces open for appropriation—a condition made possible through the modern assumption of Black a-spatiality. (Bledsoe and Wright Citation2019, 8; this point is echoed by Daley Citation2013b, 390)

Whiteness is not a “fixed, biologically determined, phenotype, but … a structural advantage, standpoint, and set of historical and cultural practices” (Faria and Mollett Citation2016, 80). Difficult to identify precisely because it cannot be captured as a fixed “thing,” whiteness is “a noncategory, normal, natural, indeed [by] achieving a ‘super-naturalness’ … a ‘racial grammar’ … whiteness becomes invisible” (Faria and Mollett Citation2016, 80). Anthropologist Pierre (Citation2013a, Citation2013b), drawing from the work of Mahmood Mamdani, explained the ways in which whiteness works alongside other forms of domination in postcolonial Ghana, including the colonial bifurcation of Ghanaian people as customary ethnic groups. The material and symbolic establishment of corporate knowledge and authority reflects the ways in which the persistent and unspoken influences of whiteness and racial difference remain central in present-day geographies of extraction.

Colonial Racism and the Rhetoric and Operations of Corporate Extraction

Coloniality, which is always already racialized, operates through the intersecting of multiple political and cultural practices and struggles, including the disavowal of racism and negations of antiracism, racial “ventriloquism,” colonial amnesia(s), willful blindness, and white and colonial “moves to innocence.” The disavowal of racism is apparent in the dismissals of antiracist work on the grounds that antiracism, in acknowledging racism, is itself a form of racism (Elliot-Cooper Citation2018). White and colonial amnesia is a set of disremembering practices that effaces the destructive practices of European colonialism and coloniality, simultaneously emphasizing colonialist projects as “civilizing missions” that harkened (or continue to harken) modernity. Racial ventriloquism is a related practice in which colonialists and elites presume to speak on behalf of (and therefore appropriate the voice and agency) of people racialized as black, brown, local, and “other” (Novo Citation2018). In postracial ideologies, as we show here, racial ventriloquism manifests itself as the superficial inclusion and arrogation of nonwhite perspectives and bodies to showcase and endorse corporate extraction.

Colonial amnesia is a form of willful blindness, by which we mean it is an active refusal to acknowledge the destructive features of colonialism. Coloniality is obscured by strategic misinformation that fosters a general ignorance, a practice known as agnotology. The production of ignorance (agnotology) is “an active construct, ‘not merely the absence of knowledge but an outcome of cultural and political struggle’” (Slater Citation2019, 23). In such struggles, colonial and corporate entities frequently rhetorically appropriate the resistance grammar and resistance toolkits of oppressed peoples (Tuck and Yang Citation2012; Kirsch Citation2014). Colonial misappropriations of “decolonizing” practices, Tuck and Yang (Citation2012) argued, are a form of “settler moves to innocence” (9). Colonial moves to innocence refers to the set of tactics and techniques through which colonialists and dominant groups capture resistance grammars and momentum by presuming to act in the name of that very resistance grammar.

In this article, we focus on key events, people, and moments of racialization in the timeline of the Chad–Cameroon Oil Pipeline (see ) as a means of examining shifting corporate rhetoric. Whereas the local is racialized and naturalized in the service of extraction, flexian elites, such as former World Bank president and private financier James Wolfensohn, exercise plastic and elastic power across the borders and scales of public and private governance. Flexians are characterized by the ability and propensity to move within and among scales, to perform changing, simultaneous, contradictory roles in the government (sometimes multiple governments), business and corporate, nonprofit, and academic spheres (Wedel Citation2009). Anthropologist Wedel (Citation2009) explained,

It is not just [their] time that is divided. [Their] loyalties, too, are often flexible. Even the short-term consultant doing one project at one time cannot afford to owe too much allegiance to the company or government agency. These individuals are in these organizations (some of the time anyway), but they are seldom of them. (1, italics in original)

The work of flexian elites is often key to the scalar logics of colonial extraction, endowing people with forms of privilege to move in and out of scalar spheres while displacing blame and distancing themselves from fallout and criticism. Flexians are distinguished from other elite groups by their unaccountability and the resultant ability to exist in the shadows of elite authority. Unlike other elite figures, the same person can be an academic authority (Harvard professor) and an authority of the Russian government (signing contracts on behalf of Russia), adopting one of whichever various changing elite roles is most appropriate and conducive to the particular moment (Wedel Citation2009). Flexian role-shifting permits the concentration of power in the hands of a small cadre under the rubric of resource governance.

As we show, flexian elite often maintain corporate legitimacies through strategic deflections of blame and postracial refusals. This includes the absolution of racism through the insistence that racist actions and racial inequalities are problems located at the scale of the individual and therefore resolved by the superficial inclusion of racialized bodies within extractive projects. The last three decades, we argue, have witnessed assorted efforts by flexian elites to incorporate local peoples and knowledges within a colonial rhetoric of corporate extraction. We refer to these broad practices within colonial extraction as racialized localwashing. Localwashing is both racialized and racially coded. Discourses of localwashing are signaled racially through synonyms that would disavow race as a structuring logic and feature, including native, tribal, traditional, ethnic, indigenous, and even grassroots and African. Localwashing rhetoric is dynamic insomuch as its production and process shift; it is at times produced through strategic colonial amnesias, willful blindness, ignorance and maleducation, or the prioritization of economic and colonial interests.

The elite rhetoric(s) of the racialized local that we refer to in this article might be actually believed by institutionally embedded elite actors—that is, maybe the people we refer to here believed that they were or are doing good. Intention and belief are not our concern; nor do we seek to impose a deterministic or simplistic interpretation of complex interactions within extractive “governance”; indeed, the rhetoric that we track herein might not have been deliberate, planned, or coordinated. Spillers (Citation2003) articulated the importance of “interstitial” thinking as a way to work against the tendency for hiatuses, intervals, and “punctualities (in a linked sequence of events) … [to] go unmarked so that the mythic view remains undisturbed” (14). Corporate omission and selected silence—that is, the production of hiatuses and gaps in official or public scripts—are widely recognized patterns of elite and corporate management strategies (Jackson Citation2013). Through interstitial thinking, we know through and despite these gaps, as a means of refusing to allow the “mythic view” of oil as development to “remain undisturbed” (Spillers Citation2003). We critique these practices and rhetoric(s) as spatially operational and materially violent, irrespective of intentionality, naiveté, or claims to benevolence or innocence.

Where We Speak From, Who We Speak With

This research is based on ethnographic and mixed-methods work with people living along the Chad–Cameroon Oil Pipeline in two rural communities in Cameroon (2012–2013 and 2018), discussions with antiextraction and environmental justice advocates, and interviews with oil consortium representatives in Cameroon. We have conducted rhetorical or visual analysis of (1) hundreds of pages of oil consortium project reports, memos, leaked internal correspondence, and briefs (written between 1998 and 2016); (2) consortium-sponsored films; (3) public forums and media discussions considering aspects of the pipeline; and (4) gray materials from transnational advocacy networks (TANs), NGOs, and activists. As such, this article builds on more than a decade of work on extraction in and beyond the region of central Africa. We situate our “locus of enunciation” (Mignolo Citation2005, 111) from our engagements in Cameroon and elsewhere with scholars, activists, and people struggling within and resisting against colonial extraction.

Decolonial perspectives emphasize the urgencies of “undoing colonialism, or perhaps never succumbing to it” (Bacchetta, Maira, and Winant Citation2019, 3). At the same time, postcolonial geographer Noxolo (Citation2017) cautioned, “Decolonial theory can become yet another instrument for time-honoured colonialist manoeuvres of discursively absenting, brutally exploiting and then completely forgetting Indigenous people” (343). Our recognition of the ongoing coloniality of knowledge demands that we remain vigilant about the ways in which our work risks replicating various aspects of coloniality; we make humble and yet-unfinished efforts to attend to decolonial options.

A Brief History of the Chad–Cameroon Oil Pipeline

Oil reserves were discovered in Chad’s southern Doba Basin in the early 1970s. At the time, corporate cost–benefit analysis appraised an extractive project to be infeasible due to an ongoing civil war in Chad, the immediate difficulties of exporting the crude (as Chad is a landlocked country), as well as the high sulfur content (and therefore relatively low quality) of the crude. The Chadian Civil War ended in 1979. In 1993, an oil consortium initially composed of Exxon, Shell, and Elf came together to discuss the prospect of a multicountry, multi-billion-dollar crude oil pipeline.

Elite within the petroleum industry faced considerable public outcry during this period, including the outrage occasioned by the Exxon Valdez oil spill in 1989. Anger was compounded by the 1995 killing of environmental and Indigenous rights activist Ken Saro-Wiwa and eight of his associates in Nigeria. The government of Sani Abacha, with Royal Dutch Shell Petroleum’s complicity of silence, had executed the Indigenous environmental activists. Meanwhile, the international publicity driven by Greenpeace around Shell’s plan for sinking the Brent Spar oil platform in the North Sea increased awareness of the ecological dangers of oil extraction. These movements were unified by a demand to wrest control of resources from the hands of powerful global corporate entities. The World Bank was brought into the project to assist in securing funding and to establish a framework for oil as development in Chad that might respond to and mitigate anticorporate and antiextractive resistance.

Throughout the 1990s, internal World Bank and consortium documents acknowledged the pressures from social movements, including those organizing against the pipeline (World Bank Citation2006). Embroiled in their own scandals (Shell’s role in the Ogoni 9 killings and Elf’s 1994 fraud scandal), Shell and Elf withdrew from the project. ExxonMobil was joined by the U.S. corporation Chevron and the Malaysian oil and gas company Petronas. In the late 1990s, World Bank president (1995–2005) James Wolfensohn unveiled an “unprecedented” development practice to address the Bank’s previous failures of development as structural adjustment. (Wolfensohn argued that intergovernmental development organizations had neglected the “social side” of the development “balance sheet.”) By 1998, the Chadian government had signed the World Bank–recommended revenue management law, which stipulated how oil revenues would be spent within Chad. In 2000, the project documents and loan contracts were signed and construction commenced.

Construction of the Doba oilfield, the Kribi offloading vessel, and the 1,070-km-long (660 miles) pipeline were completed in 2003. The pipeline passes beneath 238 villages and is within 2 km of 794 additional communities (Lo Citation2010). The pipeline required an initial appropriation of 100,000 ha of land. Described by people as “bad luck” and a “false project” (field notes 2012), the pipeline has directly and indirectly augmented and reinforced patriarchy and militarism and contributed to ongoing ecological and climate hardships in the region (Endeley Citation2010; Murrey Citation2015b). From its inception in 2000 until 2016 (the year of the last available project report), 18,000 people have been individually compensated by the consortium for the loss of access to land (Esso Chad/Cameroon Citation2016). Meanwhile, the arable land captured for oil exploration and extraction continues to expand. In March 2011, the government of Niger signed an agreement with the Chadian National Oil Company to pump crude oil through the Chad–Cameroon Oil Pipeline, a venture that involves extending the pipeline nearly 1,000 km to the Agadem oil fields.

The Racialized Localwashing of Extraction

We argue that, in response to anticorporate and antiextractive resistance alongside the rising postracial ideologies and practices of the 1990s, corporate elites engaged in perception management frameworks characterized by fluctuating processes of evoking, naming, and claiming the racialized local. Corporate and multilateral attentions to and investments in appearing to understand, take seriously, communicate with, or valorize local knowledge, local people, local ecologies, and local epistemologies are constitutive of local-centric extraction. We refer to such corporate public relations (PR) framing, claiming, and deflecting as localwashing. In this, corporate rhetoric of the local is a form of racialized and flexible scalar political power. By presuming that extraction takes place outside of racist histories of place and meaning making, localwashing functions to legitimize extractive interventions by persistently drawing on racist beliefs of white superiority and antiblackness, all the while silencing the role of race from such imagined geographies. Localwashing is one mechanism within a larger set of late-modern and postracial corporate strategies for configuring the knowledges and socioscalar power relations of extraction. This includes how localwashing acts as a means through which flexian elite influence public responses in ways amenable to extraction, dismiss antiextractive critics as nonlocal, and deflect blame in racialized scalar politics.

A few popular media articles have deployed the term localwashing to refer to corporate action on the consumption side of capitalist chains. The Web site Grist.org, for example, listed corporations currently engaging in what they referred to as the “ingenuity/absurdity/deception” of localwashing. Hellmann’s Mayonnaise, Barnes & Noble, and Citgo are among those listed.1 Advertisement, branding, and marketing campaigns draw on images of often essentialized local people and places to demonstrate the “changing face” of corporate action. No longer the globalized “footloose” entities without ethical or social responsibilities to any one people or place (Bryant and Bailey Citation1998), localwashing ad campaigns seduce consumers with impressions of “buying local.” Corporate manufacturers tout their products as “locally sourced” or consisting of “local flavors.” Yet, localwashing has not yet been considered seriously in academic research. In this, we offer a preliminary consideration of the usefulness of the concept in understanding corporate actions, rhetoric, and processes on the production side of capitalism.

Localwashing the Chad–Cameroon Oil Pipeline

An analysis of flexian representational strategies within the Chad–Cameroon Oil Pipeline reveals a set of racialized corporate narratives about the local. We refer to these hegemonic claims as efforts to localwash otherwise unaltered structures and logics of colonial and extractive interventions. These sometimes-conflicting productions, frames, and diffusions of the local include the following:

An unpopulated, absent, or empty local.

A victimized local in need of intervention.

A local suffering at the hands of an “inept” racialized African state.

An amenable, passive, and static local supportive of extraction.

A violent and insurgent local capable of disrupting extraction or siphoning profits and therefore in need of surveillance and securitization.

An irresponsible local guilty of misusing reimbursement and compensation funds and therefore accountable for their own impoverishment.

This list of corporate-extractive imagined geographies of local people and places, albeit far from exhaustive, reveals some of the malleability, miscellany, and sharp incongruity of flexian and nonflexian elite belief and rhetoric in regard to the local people and geographies within extractive projects. Some of these hegemonic, essentialized, and superficial local framings have been addressed elsewhere, and we do not seek to reproduce this literature here (on absent, essentialized, static local, see Coronil Citation1996, Citation1997; Briggs and Sharp Citation2004; McKittrick Citation2013; on resisting local, see Bosworth Citation2018). Our focus is on three broad and often interrelated and overlapping multiscalar practices through which flexian elite affect racialized localwashing: (1) anguishing, (2) arrogating, and (3) admonishing the local. Through the rhetoric and practice of anguishing, corporate elites then render racialized bodies as spectacles of suffering to legitimize claims about acting on behalf of the local. Through the rhetoric and practice of arrogating, elites disappear and deny the multiple agencies of people racialized as nonwhite, calling on select local figureheads to speak, ventriloquize, or stand in as unidimensional supporters and endorsers of extraction. Through the rhetoric and practice of admonishing, elites blame racialized bodies and institutions for colonial difference and the failures of the promises of oil as extraction.

Anguishing

The Corporate Gaze: The Performance and Spectacle of Suffering and Victimhood

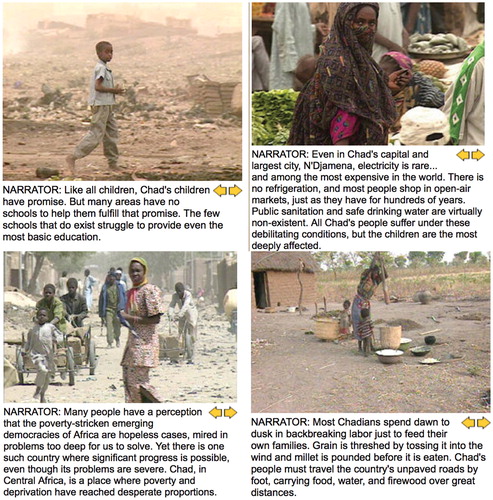

In the late 1990s, the U.S. company Winner and Associates produced a twenty-minute film titled The Chad/Cameroon Development Project: Views and Voices on behalf of the oil corporation ExxonMobil’s upstream affiliate in Chad, Esso Chad (see ). The film was a promotional tool self-described as a “module,” a term that denotes its presumed instructional value. Views and Voices was not the only video produced and diffused on behalf of the oil consortium. The consortium-sponsored film Chad, Land of Promise (Citation2003) had been released a few years earlier (see ). These films were part of a larger PR campaign to quiet transnational concerns about the environmental, social, economic, and political consequences of the pipeline.

Figure 2 A corporate feedback loop establishes a baseline rhetoric of local suffering. Screenshots from an oil promotional video, The Chad/Cameroon Development Project: Views and Voices (Citation1999). Source: The Chad/Cameroon Development Project: Views and Voices (Citation1999). Collage by author.

Figure 3 A collage of colonial imagined geographies of “local” African landscapes. From the top right is an opening scene of the oil consortium promotional video, Chad, Land of Promise (Citation2003), capturing the sun setting on an oil rig. This image has been juxtaposed with countless other iterations, each reflective of the pervasive colonial fantasy of the “promise” of “empty” frontier spaces in Africa. Collage by author.

In the opening scene of Views and Voices, the pipeline is introduced by first describing “life in Chad” for the spectators. The narrator declares,

According to the World Bank, Chad is the fifth poorest nation in the world. It is a country whose people suffer from poor health care, inadequate education and a lack of roads, electricity, safe water, and sanitation. The impact of these conditions is difficult to comprehend without seeing them. This module illustrates the difficulty of daily life in Chad. (The Chad/Cameroon Development Project: Views and Voices Citation1999)

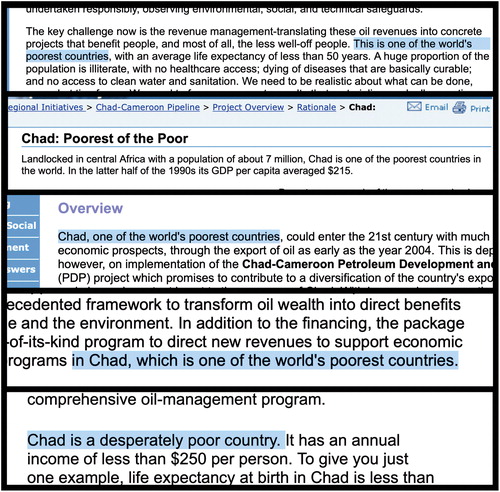

Data from the World Bank were inserted into a corporate feedback loop, to situate the pipeline within a racialized imaginary of “local” and “African” suffering (see ). Life in Chad is described as one of extreme hardship, void of industrial amenities and infrastructures. Such a life, the narrator commiserates, is “difficult to comprehend” for the audience:

Figure 4 Online archives of the World Bank Group’s public briefings and press announcements regarding the Chad–Cameroon Oil Pipeline (1999–2005). These selected sites illustrate the frequency of references to and naturalizations of poverty in the early phases of the project. Source: World Bank Group. Collage by author.

The development of Chad’s oil fields is currently the only opportunity the country has for economic development. … Chad desperately needs to take maximum advantage of this opportunity. … Chad’s poverty is deeply entrenched, its human suffering widespread.

In a documentary film produced by the French television channel Planète, the director-general of Esso Chad, Ronald William Royal, takes viewers on a tour of the extraction zone (see ). Walking through the base station, Royal explains, “Now you need to remember that you’re in Africa, okay? There was nothing here … there was no electricity.” During a later visit to a schoolroom, children stand and perform memorized responses for Royal and the film crew, in an oft-repeated spectacle constructed to reveal local enthusiasm and welcome for intervention in Africa.

Figure 5 The former director of Esso Chad, Ronald William Royal, tours Esso facilities and neighboring towns in southern Chad. Source: Tchad: Main basse sur l’or noir (Citation2005). Collage by author.

Scholars have provided nuanced critiques of the dehumanizing effects of such representations of victimhood, which infantilize people and strip them of agency (Said Citation1978; Spivak Citation1988; Escobar Citation1995). The “[c]oloniality of being … [affected a] dehumanization and depersonalization of colonized Africans into damnes (the condemned people and the wretched of the earth)” (Ndlovu-Gatsheni Citation2013, 9). The imagined geographies of a particular “Africa” (Mudimbe Citation1988; Ndlovu-Gatsheni Citation2013)—the “Africa” of victimized bodies in places of poverty, conflict, underdevelopment, “failed states” (Gruffydd Jones Citation2013)—supplied the foundation on which corporate entities established legitimacy, authority, power, and knowledge “expertise” on and for “the African local” (Daley Citation2013b, 390; Daley Citation2013a). These imagined geographies are “at odds with the diversity of peoples, cultures and environments” (Sharp Citation2009, 13). Indeed, these are not places so much as projects (Prashad Citation2007). Geographies of racialized difference are constructed not by the people in or from “local” places but prior to an engagement with them—so that any “empirical evidence … [is] fitted into the categories that were already constructed” (Sharp Citation2009, 13, italics in original).

A decolonial critique of corporate flexians and rhetoric builds from Césaire’s (Citation1953) important “declaration of war” against colonial imaginaries. In Discourse on Colonialism, Césaire wrote that the colonizer is or was compelled to create false narrations to justify his presence and active colonization. Césaire (Citation1953) called this the “collective hypocrisy that cleverly misrepresents problems … to better legitimize the hateful solutions provided for them” (32). More than fifty years later, Césaire’s analysis of colonialism remains relevant in explaining the corporate rhetoric of racialized localwashing in the Chad–Cameroon Oil Pipeline. Racialized discourses of victimhood and saviorhood provoke forms of “dangerous optimism” in the potentials for colonial and capitalist solutions to colonial and capitalist problems. Local-centric extraction reflects ongoing patterns of racial capitalism grounded on persistent mythologies of whiteness, in particular whiteness as benevolence and antiblackness.

It is partly this imagined geography that allows us to understand how and why those forty policymakers and policy students at the UCT seminar (which we mentioned in the introduction) voted to pursue and support a project like the Chad–Cameroon Oil Pipeline, even in the face of its numerous failures. Local-centric interventions are contingent on the perpetual racist refashionings of the local as subordinate and therefore continuously receptive of projects informed by nonlocal political and socioeconomic concerns and priorities. The politics of scale helps to explain the performative power of localwashing by flexians within international milieus. Localwashing is received as legitimate, even well intentioned, within wider publics because it occurs within the scalar politics of racialized global capitalism that condones persistent racialized representations of “local” and “African” people and places (Daley Citation2008). The spectacle of suffering is centrally important for the maintenance of the system of power. This is because the sets of beliefs constitutive of racialized colonial power are contingent on the “constantly renewed destruction” of African bodies as well as the rendering visible of that suffering in ways that occlude socioeconomic causality (Segato Citation2016, 620). Through the perpetuation of the baseline rhetoric of suffering, corporate elite make various forms of intervention necessary for the preservation of life. Daley explained that the effect of such discourse is the dismissal of criticism. She wrote, “Claims of unaccountability, false authority and racism [can be] brushed aside as minor, because of the urgency of the need to save lives” (Daley Citation2013b, 390). For intervention to be imminently needed, the local must never escape the position, role, and function of subordination within the racialized politics of scale.

Localwashing from Anticorporate Critics

That the world order is structured through coloniality meant that even critics of the Chad–Cameroon Oil Pipeline frequently drew from and evoked a racialized rhetoric of entrenched human suffering to contextualize their critiques of the extractive project. Wysham (Citation2008), a longtime member of an international network of activists against the project, wrote of a “harrowing” journey from Doba to N’Djamena: a place “littered with the detritus of the oil rush” in a “dangerous country.” During one nighttime ride, the vehicle narrowly escaped a possible snare set by les coupeurs de route (road bandits) and, in a scene described in visceral detail, crushed a dog. Other civil society and advocacy groups critical of the World Bank and the oil consortium drew on similar naturalizations of poverty to argue against the project.

In 2016, U.S. journalist Rachel Maddow did an extended exposé of oil extraction in Chad, critiquing the role played by U.S. President Donald Trump’s selection for Secretary of State, Rex Tillerson. Tillerson was the CEO of ExxonMobil at the time that the company was developing the pipeline. In the opening sequence, Chad is described as “one of the poorest countries on earth, it is considered to be one of the most corrupt countries … and the rest of the world, sadly, has never much cared” (Maddow Citation2016). U.S. investigative journalist Steve Coll’s oft-repeated description of Chad, for example, also echoes that of the oil consortium. In a 2011 talk at the Carnegie Council about how ExxonMobil acts as a “global empire,” he introduced the pipeline by first establishing “a context.” He said, “Chad, which is a really moving and benighted place, fortunately only 11 million people live there, but it’s a pretty miserable place … kind of a fourth world country, really” (Coll Citation2011). He repeated this description almost verbatim in several additional public forums (available on YouTube, see, e.g., Coll [Citation2012]). These flexian narratives of anguishing obscure the heterogeneity of human experience while preserving the colonial logic of benevolent interveners concerned with poverty eradication. Anguishing, as a method of racialized localwashing, would deny the agency of people, while claiming to act on their behalf.

Although people’s accounts of life along the pipeline have been dissimilar, they are alike in challenging corporate visualizations of them as eagerly compliant to or endorsing of extraction in their communities (Endeley Citation2010; Murrey Citation2015b, Citation2016). Embodied experiences of the historical duration of colonial violence were illustrated in people’s compounding accounts of physical pain and emotional discomfort across time (field notes 2012, 2013, 2018). People in Nanga-Eboko and Kribi, two towns along the pipeline, spoke of being “treated worse than animals,” being “treated like slaves,” and being “recolonized” (field notes 2012, 2013). By drawing on critiques of colonialism, slavery, and imperialism, people characterized and described their experiences with awareness of historical and structural patterning (field notes 2012, 2013). These sentiments reflect a consciousness critical of corporate and hegemonic racializing rhetoric and racist practice.

Arrogating

Corporate Naming, Claiming, and Ventriloquizing the Local

In September 2000, Wolfensohn made a bold statement about “African” support for the Chad–Cameroon Oil Pipeline. He declared,

I have one thousand Africans working at the Bank, who unanimously support the Chad–Cameroon Pipeline. And I vigorously support the Chad–Cameroon Pipeline. This is not for the people in Berkeley to decide [referring to Northern-based advocacy organizations]. This is for people in Chad to decide. And I think it’s important that we have a proper balance between the Berkeley mafia and the Chadians and I, for my part, am more interested in the Chadians.

Wolfensohn’s statement about “vigorous” support for “people in Chad” and his condescension for “the Berkeley mafia” in the context of the Chad–Cameroon Pipeline demonstrate another aspect of the rhetorical function of the local in legitimizing corporate extraction. Wolfensohn showed little hesitancy in claiming the voice of “all Africans” working at the Bank and then mobilized an essentialized “African” identity to speak on behalf of “the Chadians” and against irrational and mafia-like “nonlocals.” His words conjured a pan-African network of support for the project. He later declared, “Every president of every African country supported the Chad–Cameroon Pipeline” (Mutume Citation2000, italics added). These declarations were neither exceptional nor transient.

Rather, Wolfensohn’s words evoke the strategic “face value” of the incorporation of “Africans” within extraction. Critical legal scholar Leong (Citation2013) argued that a defining feature of racial capitalism is “the process of deriving social and economic value from racial identity” (2152). This is reflected in those particular patterns within “predominantly white institutions [that] use nonwhite people to acquire social and economic value” (Leong Citation2013, 2152). Indeed, a central marker of postraciality has been the strategic rendering visible of bodies of color, predominantly black and African bodies, in support for racist, colonial, and capitalist projects and endeavors. Kendi (Citation2016) explained, “Black people … always proved to be the perfect dispensers of racist ideas” (290). Racialized localwashing frequently entails an instrumentalization of African and black bodies, collaborators, and knowledges for racist and extractive projects. Such incorporations were meant to signify racial harmony as well as the fulfillment of corporate social responsibility (CSR). At the same time, those “1,000 Africans at the Bank” did not enjoy equal opportunities for recruitment, promotion, or retention within the institution. Racial discrimination within the World Bank has been documented by ethnographers and journalists and substantiated by internal task force reports (Edwards Citation2009).

In another effort to localwash the project, a Paris-based Senegalese dance troupe was flown to the 1999 World Bank and International Monetary Fund annual meetings in Washington, DC, to “support” the pipeline. At the meetings, corporate elite held them up as “Africans” who had come to “show solidarity with the project” (Horta Citation2002, 176). A group of Chadians and Cameroonians were flown in to lobby for the project under the auspices of representing “local” civil society. Horta (Citation2002), a senior environmental economist at Environmental Defense and a longtime critic of the pipeline, noted that none of these people had known affiliations with civil society groups on the ground. “Embarrassingly,” she explained, “their written statement was identical to an official statement in support of the project published by the Chadian embassy” (Horta Citation2002, 176).

Such episodes reveal the one-dimensional evocations of “the local,” in which any African person functions to localwash corporate action. In the context of natural resource extraction in Ecuador, Novo (Citation2018) similarly identified ventriloquism as a tool of racist domination in which non-Indigenous people speak on behalf of Indigenous people. In postracial rhetoric, geographic, linguistic, and cultural distinctions are flattened to allow a rapid and superficial incorporation that suits corporate interests and reflects the colonial logics of white institutions. Localwashing strips the local of internal diversities by simplifying social and political relations within local places and discursively erasing—that is, cleaning or whitewashing—the project’s profit incentives and local destructions in favor of a rhetoric of local support. Whitewashing denotes the simultaneous “persistent silence … about race [alongside the ongoing] racialization in the present era, [which is] one of ostensible racial blindness and progress” (Inwood and Martin Citation2008, 392; see also Pulido Citation2015). Localwashing, as an extension of the logic of whitewashing, is a postracial hegemonic tactic of framing and interpreting practices of racial dominance in ways that would silence the role of race in structuring that very domination. Indeed, “[r]acialization sometimes appears as flat-out ignorance; it might look ridiculous if it did not do so much damage” (Bacchetta, Maira, and Winant Citation2019, 12).

Wolfensohn’s evocation of “African support” occurs within a global racial hierarchy characterized by antiblackness and white dominance. These claims are demonstrative of a modern global political economy in which racialization is and has been embedded in economic relations (Tilly and Shilliam Citation2017). Corporate entities use multiscalar tools to visually and hierarchically separate consuming centers from producing margins (Mantz Citation2008); the result is a more effective exploitation of resources (Mitchell Citation1991; Apter Citation2008). Localwashing obscures the operations of structural racism, while drawing on the unstated authority of whiteness to determine what is good, rational, profitable, and possible.

Passive and Static Local Support for Extraction

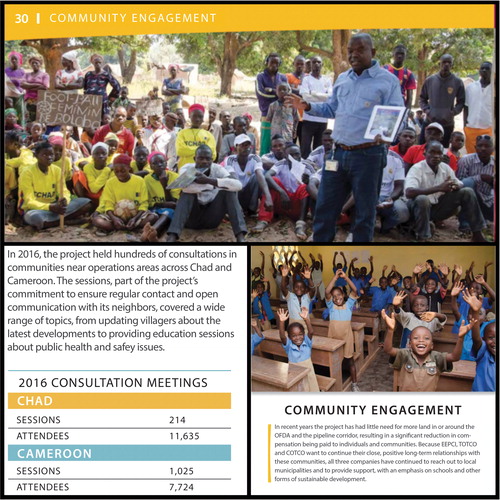

Another form of localwashing was the rhetoric of unprecedented local collaboration propagated through the consortium’s public documents and reports. In the thousands of pages of project guidelines, spending regulations, and environmental policies, the consortium communicated a rhetoric of accommodation for “local” concerns and participation (see Cooke and Kothari [Citation2001] on the seductive rhetoric of "participation"). According to ExxonMobil, the consortium conducted more than 1,000 village meetings or “consultations” in the year 2000 alone (ExxonMobil Citation2008). We calculated the cumulative numbers cited within the consortium’s thirty-six reports: Approximately 550,000 people have been “consulted” during the pipeline’s eighteen years of gestation and utility (the last annual report calculated was from 2016). The manners and practices through which these “public information campaigns” occurred remain unclear, although there is occasionally reference to some of the subjects discussed. For example, publications from Esso Cameroon (ExxonMobil’s upstream affiliate in Cameroon) describe “routine consultations” in two Cameroonian towns: “participants discussed what to do if they notice something out of place along the [pipeline] right of way. The meetings are also an opportunity for locals to receive information about project activities and to raise any questions, concerns or requests they may have” (Esso Cameroon Citation2013, 26). There is no explanation within the documents of what these “questions, concerns, or requests” might be. The Community Engagement blurb of Esso’s publicity campaign contains similarly vague language. The Community Consultation section of annual reports generally includes an image (or several) of seated groups of Chadians or Cameroonians looking passively at consortium representatives (see ).

Figure 6 Images of a passive and supportive local appear throughout the pages of Esso’s Year-End Reports for the Chad/Cameroon Development Project. Source: Esso Chad/Cameroon (Citation2016). Collage by author.

The president of the Chadian Association for the Promotion of the Defense of Human Rights, Delphine Djiraibe, argued that the consortium’s consultations did not signal consequential exchanges between engineers, representatives, and local people. She wrote, “The presence of the military during the consultative sessions was enough to dissuade people from expressing their opinions” (Djiraibe Citation2000). A former World Bank spokesperson, Robert Calderisi, described the presence of armed guards in a narrative that echoes earlier colonial imaginaries of noble colonialists braving dark and dangerous Africa for the good of “natives.” He wrote:

Exxon employees visited settlements along the pipeline route, accompanied by soldiers or armed security personnel. Critics argued that the presence of the guards had prevented the Chadians from expressing their views freely. [However,] Exxon staff, mostly security-conscious Americans who were new to Africa, were risking life and limb to find out what farmers and their families thought. (Calderisi Citation2006, 185)

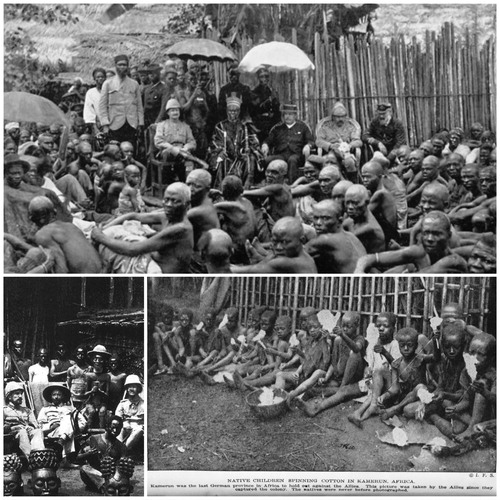

Although these ideas have shifted over time, the genesis of corporate ideas of the subservient and receptive local lie in precolonial corporate imaginaries in which European corporations were initiators of what was euphemistically termed the “civilizing mission” (see ).

Figure 7 Juxtaposing oil consortium images with images from colonial archives reveals similarities in visual aesthetics and the colonial fantasy of a passive local. Top: A ceremony marking the formal “incorporation” of the Ewi of Ados Kingdom into the British Lagos Protectorate, 1897. Source: The Queens Empire: A pictorial and descriptive record. London: Cassell and Company, 1897–99 (FCO Historical Collection DA11 QUE). Bottom right: Photograph of children spinning cotton in Kamerun (Cameroon) in 1919. The original caption reads, “Native Children Spinning Cotton in Kamerun, Africa. Kamerun was the last German province in Africa to hold out against the Allies. This picture was taken by the Allies since they captured the colony. The natives were never before photographed.” Source: Kelly Miller’s History of the World War for Human Rights, originally published in 1919 by A. Jenkins and O. Keller. Bottom left: Young boys surround seated German colonists in Bamoun, Kamerun/Cameroon, 1905. Collage by author.

During discussions with people along the pipeline in Cameroon, people overwhelmingly reported feeling either left out of consortium decision making and information loops or being deliberately misled during such “consultations” (Swing, Davidov, and Schwartz Citation2010; Murrey Citation2015a, Citation2015b). People in one community indicated that they were excluded from participating in pipeline-related discussions and that when complaints were filed they were often intentionally squashed by consortium representatives (field notes 2012; see also Leonard Citation2016).

These information sessions were designed in part to ensure the security and material integrity of the pipeline rather than to establish meaningful dialogue between local stakeholders and consortium representatives. Public information campaigns were a strategic component of maintaining the material integrity of the right-of-way by requesting nearby communities to function as “eyes and ears” along the pipeline (field notes 2012). People were instructed to be alert to and report any unusual vibrations, leaking crude, or suspicious behavior along the pipeline (field notes 2012, 2013). Corporate interests were prioritized during these sessions, even as reports would later hold them up as examples of their “responsible” behavior. Horta noted:

There were never “real” consultations … it was always kind of promoting the project and getting people’s hopes up. … I remember that one of the big consultations was only announced in the newspapers on the day of the consultation itself. So people couldn’t actually participate. (Interview with author, 22 February 2012)

These corporate–community sessions could result in codifying and policing the field of possible community responses to extraction rather than fostering meaningful interchange (Lo Citation2010; Leonard Citation2016; Murrey Citation2016). Corporate consultations can be occasions for corporate entities to restrict autonomy of grassroots action by (1) “domesticating opposition or co-opting or transforming it to align more with state or corporate agendas” (Sawyer and Gomez Citation2012, 5); (2) impeding people’s “psychological freedom” by directing decision making into certain corporate-friendly conduits (Maher Citation2018); (3) producing neoliberal subjectivities that limit the venues and vocabularies in which complaints are either taken seriously or go unrecognized (Leonard Citation2016); and (4) exacerbating internal community divisions or creating new tensions (Obi Citation1997; Murrey Citation2015a, Citation2016).

Admonishing

Dismissing Critics as Nonlocal

A sizable coalition of people, advocates, and activists working against the pipeline emerged early on in the pipeline’s planning and negotiation phases. This diverse network of several dozen national and international NGOs organized for “certain minimum conditions” to be met before the pipeline’s construction (Djiraibe Citation2000, 2; see also Horta Citation2002; Swing, Davidov, and Schwartz Citation2010). Among other objections, they expressed doubts that the international framework for development was practical in the sociopolitical contexts of both countries.

In response, the consortium deployed a campaign of NGO disparagement, casting international NGOs as self-promoting and distant interlocutors, and the World Bank engaged in a tacit pacification of NGO concerns. Leaked correspondence between Jean-Louis Sarbib, the World Bank vice president for Africa, and Ian Johnson, head of environment of the Bank Information Center, revealed their objective: “secure support for the project” by “buying time from critics [and convincing NGOs that they] are really prepared to listen, learn and eventually make some proposal that might mollify them” (World Bank memoranda, August 1999, as cited in Breitkopf Citation2002, 22). Horta (Citation2012) explained that “behind the scenes, the World Bank’s main concern was to silence the NGO call for a moratorium” (213). The silencing of criticism was conducted in part by a stalling tactic Sarbib and Johnson called “listening missions” (memo from Sarbib-Johnson 1999). That the quotations around “listening missions” are original to this leaked exchange reflects an inflection of sarcasm into the process. These so-called missions were intended to create the appearance of listening and hence maintain the illusion of the Bank as receptive to negotiation—while the project’s planning and engineering moved forward.

In 2000, Wolfensohn dismissed the networks that advocated for local rights against Bank-funded projects as too international and too distant from the realities of local people in Chad and Cameroon. These groups were imposing an “external” decision making on “people in Chad.” A host of “eminent” former World Bank employees, journalists, and academics were similarly vocal in their criticisms of NGO involvement in the negotiation and design phases. Activists and TAN representatives were aware of these tactics, as Djiraibe outlined in her final project report:

Project proponents mounted a campaign to discredit NGOs by saying that northern NGOs were misleading southern NGOs. The claim was that northern NGOs were unaware of the poverty conditions in Chad and Cameroon. The objective of this campaign was to “delegitimize” NGOs’ work by saying that they had no mandate to speak on behalf of people on the ground. (Djiraibe Citation2000, 6; see also Horta Citation2002, 176)

Calderisi (Citation2006) argued that the Environmental Defense Fund’s opposition to the pipeline was little more than “a litmus test of their strength as a public interest group or a trophy for display on their entrance hall for future donors” (184–87).2 The dismissal of TANs and transnational NGOs as foreign-driven was also reflected through the responses of several World Bank officials to Harvard Law School’s 1997 critique of the project’s revenue management system. During testimony before the U.S. Congress Subcommittee on Africa, a consultant to Human Rights Watch/Africa Watch, Peter Rosenblum, recounted an instance of flexian elite exerting personal pressure:

A number of Bank officials, who are also alumni of Harvard Law School, called the office of the Dean of the Law School to complain. … One of them, a senior official in the legal department of the Bank, told us, essentially that Africa “did not need a group of Westerners parachuting in to tell them what to do.” (U.S. House of Representatives, Committee on International Relations, 18 April Citation2002, Serial No. 107-75)

The former director-general of the Independent Evaluation Group at the World Bank, Robert Picciotto (Citation1995), argued that some NGOs represented “narrow and privileged constituencies” and therefore needed either to police themselves or “be restrained to work for the common good both by the workings of the market and by the enabling environment of the state” (10). Within the academy, Pallas (Citation2013) argued that TANs, by targeting projects of “recognized democratic” governments rather than international projects (e.g., structural adjustment writ large), tended to undermine democracy at the expense of the World Bank’s valuable development work.

The Financial Times and Washington Post journalist and Council on Foreign Relations fellow Sebastian Mallaby (Citation2004b, 353), on the other hand, criticized Wolfensohn’s reluctance to disengage with NGOs and noted the usefulness of “muddied” NGO accounts for the consortium. By muddied Mallaby meant those activist groups that combined issues of social well-being with environmental justice. He argued that the Bank and the consortium “rebutted the social and environmental charges easily: they had the facts, they had [the anthropologist] Ellen Brown and all her data, and many of the NGO screamers had never been to Chad” (Mallaby Citation2004b, 353). By labeling civil society actors as “the Berkeley mafia” and as “screamers” with “muddied narratives,” Mallaby and others delegitimized the critics of the pipeline as irrational, distant, and inauthentic on the basis of their nonlocalness—while reinvoking the chronicling of local poverty. These arguments also bolstered the expertise of the consortium, and more particularly the Bank, as well placed to manage the complicated landscape of oil extraction so that project proceeds were scaled in a way that was inclusive of the local. As a PR tactic, localwashing delegitimizes critics on the basis of their own supposed nonlocality.

In this way, localwashing signals a common feature of corporate response to critique: the admonishing of critics through an appropriation of their own critical vocabularies (Kirsch Citation2014). The focus on the “local” and “grassroots” was a cornerstone of anticorporate, antiglobalization, and environmental movements of the 1990s and early 2000s. The local was repackaged to both efface the violence of extraction and endorse corporate action as legitimately concerned about local people and environments.

Scalar Displacements of Blame: The “Failed” African State

On 9 September 2008, four days after the government of Chad had repaid the loans incurred through the pipeline to the World Bank, the Bank announced that it was unable to continue its support for the Chad–Cameroon Pipeline.3 The Bank’s press release indicated that the social welfare portion of the project had foundered because the Chadian government had “failed to comply,” noting an aspiration for future “cooperation … for rebuilding a development program that supports the poorest people in the country” (World Bank Citation2008). The Bank provided an ahistorical and apolitical description of their exit—one that erased the socio-politics of the extractive context and effected a “move to innocence” (Tchad: Main basse sur l’or noir (Citation2005); for a description of the Bank’s revenue management re-negotiation meetings with Chad, see U.S. Embassy N’Djamena Citation2006).

The corporate reorganization of perception management (triggered by pressures from antiglobalization and antiextraction protests) was exemplified by the rise of CSR. CSR within World Bank practices included (1) a switch from development as structural adjustment (based on orthodox notions of comparative advantage) to development as governance (based on neo-institutional economic notions of institutionally ingrained economic inefficiency); (2) the institution of the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative; and (3) promises made by key corporate actors (from Wolfensohn, to Friends of the Earth President, Ricardo Navarro) that the Bank would institute an extractive industries review (EIR) process to critically examine their support of extractive industry projects (Jackson Citation2013). Each of these initiatives nominally arose in separate spheres, but they reflect a unified set of corporate strategies to represent business and intergovernmental organizations as being sensitive to the needs of the local. In particular, each of these policy changes pivoted on a colonial narrative of local people as being “betrayed” by their “corrupt” and “ineffective” governments.

A cornerstone of corporate self-management is a refusal to admit to fault or wrongdoing. Publicly, corporate flexians propagated the self-image of the consortium as well-intentioned intermediaries and, above all, ultimately not responsible for failure. During a visit to Bero town in the extractive zone in southern Chad, the director of Esso Chad listened briefly to one man’s complaints about the oil pipeline before interjecting, “My advice to you is to stop turning to Esso and to go see your government and tell them that now the government has the resources for the local population.” The racialized localwashing of the pipeline also extended to the blaming of the local for project failures. In response to indications of heightened levels of poverty in the region, local officials and informal rhetoric emerged accusing the local of misspending, irresponsibility, and alcoholism (field notes 2012). This rhetoric echoes colonial tropes of the native as agents of their own misfortune.

Scale is central in such corporate negotiations and blame displacements. Corporate elite rework “socio-spatial processes [that] change the importance and role of certain geographical scales … alter[ing] the geometry of social power by strengthening the power and the control of some [scales] while disempowering others” (Swyngedouw Citation2010, 7). Blame and responsibility for failures are deflected onto other scales of social activity (Escobar Citation2001; Daley Citation2008). Hegemonic scalar jumping includes the manner in which corporate flexians and institutions absolve themselves of culpability or forge alliances within globalized scalar processes. Racialized localwashing was crucial to corporate tactics of scalar blame diffusion in the Chad–Cameroon Oil Pipeline.

Such corporate rhetoric reflects a multiscalar racialization of African institutions and peoples across scales within extractive capitalism (Daley Citation2008) and denotes the continued prominence of whiteness and white hegemony in framing and normalizing corporate regulation, tactics, and alliances. As we have shown, TANs are dismissed as nonlocal. Meanwhile, African states are racialized as incompetent, greedy, or villainous; as the exploiters and mis-managers of the local and hence the root cause of local suffering. The reification of an African state as incapable of serving the needs of its citizens further legitimizes the ideologies of colonial interventions—setting the tone for future extractions.

Conclusion

This article has brought together literature on decolonial thought and racial coloniality, feminist politics of scale, and geographies of extraction to challenge colonial rhetoric and localwashing within extraction. Flexian elite make localwashing work by appropriating the agencies and heterogeneities of people, racializing the local as inferior, passive, and receptive of extractive interventions. Localwashing operates within a constellation of configurations of whitewashing, including those long-standing imperial and colonial practices of blanching violence through self-celebrations and strategic suppressions, falsification, and appropriations of other knowledges. Operating like corporate “greenwashing,” which would legitimize corporate projects through a veneer of ecological (i.e., “green”) responsibility, elites use localwashing to appropriate the language of local rights, knowledge, and bodies for corporate projects. In doing so, they legitimize corporate extractions as socially and locally responsible, invisibilizing the violence(s) of extraction. More work is needed on the role and function of localwashing in other industries and economic spheres within racialized systems of power, including more recent articulations thereof.

In addition, more work is needed on the roles that academics play at all scales as experts in the structuring and querying of the local within the contested spaces of extraction. This includes serious considerations of the roles of scholars in authoring governance plans and reports as well as their roles as critical interlocutors for the control of physical space in service of extractive projects (see Grovogui and Leonard Citation2007). For example, at various stages of the pipeline’s development, representatives of ExxonMobil and the World Bank drew on and cited anthropological scholarship to support the consortium’s understanding and integration of the local into the structures of the project. How does social science scholarship render the local clean, passive, coherent, or receptive for extraction’s legitimizing narratives? Fundamentally, how do academics account for their roles in promoting localwashing, and how are they and other elite held accountable for their roles? Are they acting to contribute to the production of knowledge or are they, like other elite, complicit in mobilizing racialized logics of localwashing? This article does not directly address these questions, but we do foreground the importance of more work in these areas.

At the same time, academics have documented the material and psychological damages incurred at the scale of the “local” through extractive projects. In this context, the late anthropologist Coronil (Citation1996) stressed the need to analyze “not a reality outside representation that analysis can apprehend directly, but … the effects of existing representations [so that we may] contribute to developing more enabling ones” (75). From this engagement, we argue for the continued need for academia as both an object of study and more effective interlocutor in the geographies of coloniality and extraction. Moving forward, we “should intensify our efforts to be ‘unscrupulously vigilant … about our complicity’ … [and must continue to] ‘think otherwise’” (Baaz and Verweijen Citation2018, 66).

We find Daley’s comments on the political potentials of agency to be fruitful here. She wrote:

Enabling political “agency” is not “a romantic argument,” but a recognition that sustainable solutions lie not with … interventions, but in the capacity for people to champion their rights within the local and national space, and a recognition of the lived realities of [people] which … may suggest new ways of reimaging the political community. (Daley Citation2013a, 909)

In the context of racializing and racist extractive intervention, we draw on a politically attuned geography sufficient to the tasks of (1) critiquing the multiscalar racializations of corporate hegemony in local-centric extractive intervention; (2) imagining and assisting in the creation of other worlds; and (3) holding ourselves and others accountable for our represented and lived locations within and movements through contested spaces of the academy and colonial extraction. An antiracist double critique is necessary, one that relates contemporary and historical patterns of intervention and extraction with the critique of the racializations of these processes.

Corporate imagined geographies of the local reflect corporate beliefs, rhetoric(s), and PR mechanisms and not a “real” geography or people. Nine years after the oil began pumping through the pipeline, Elie reflected on the destruction of his farm during the pipeline’s construction. He scoffed dramatically when asked about his experiences living near it. Reflecting on his community’s sweeping dissatisfaction with the consortium’s rhetoric of development, Elie said, “Can the pipeline not explode? Can it not be broken?!” (field notes 2012). The demystification of the racist corporate rhetoric of localwashing is a provisional move toward the disruption of extraction.

Acknowledgments

We benefited from countless important conversations and exchanges during the researching and authoring of this article. In particular, we are grateful to the people in Kribi and Nanga-Eboko who live along the pipeline and who have shared their stories and experiences with us. We are grateful to Patricia Daley, Simon Batterbury, and our anonymous reviewers for their generative critiques and feedback on earlier drafts of this article. Judith Verweijen and Alexander Dunlap put together a series of panels on “Reactions from the Top within the Extractive Industry” at the Political Ecology Network (POLLEN) Biennial Conference in 2018; our participation there enriched the early iterations of the ideas explored here. Any errors of fact are our own.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Amber Murrey

AMBER MURREY is an Associate Professor of Human Geography at the School of Geography & the Environment at the University of Oxford and a Fellow at Mansfield College, South Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3QY, UK. E-mail: [email protected]. She is a decolonial political geographer who works on resistance, extraction, and antiracist scholarship in Africa.

Nicholas A. Jackson

NICHOLAS A. JACKSON is a Research Scholar in International Development with the Ronin Institute and an Honorary Research Fellow with the Coventry University Center for Agroecology, Water and Resilience, Ryton-on-Dunsmore, Coventry CV8 3LG, UK. E-mail: [email protected]. His current research interests include corporate response to social movements within extractive industries and the politics of narrative culture in the contested academy.

Notes

1 The list of localwashing in marketing and sales is available from Hiskes (Citation2009).

2 Mallaby (Citation2004a) downplayed his rhetoric with more balanced statements about NGOs during a Robert F. Kennedy Center for Justice and Human Rights public debate in 2004.

3 These were loans incurred through the International Financial Corporation, the private-sector arm of the World Bank, which raised US$200 million in financing for the project.

References

- Abourahme, N. 2018. Of monsters and boomerangs: Colonial returns in the late liberal city. City—Analysis of Urban Trends, Culture, Theory, Policy, Action 22 (1):106–15. doi: 10.1080/13604813.2018.1434296.

- Appel, H. 2012. Offshore work: Oil, modularity, and the how of capitalism in Equatorial Guinea. American Ethnologist 39 (4):692–709. doi: 10.1111/j.1548-1425.2012.01389.x.

- Apter, A. 2008. The pan-African nation: Oil and the spectacle of culture in Nigeria. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Baaz, M. E., and J. Verweijen. 2018. Confronting the colonial: The (re)production of “African” exceptionalism in critical security and military studies. Security & Dialogue 49 (1–2):57–69. doi: 10.1177/0967010617730975.

- Bacchetta, P., S. Maira, and H. Winant. 2019. Introduction: Global raciality, empire, postcoloniality, decoloniality. In Global raciality: Empire, postcoloniality, decoloniality, ed. P. Bacchetta, S. Maira, and H. Winant, 1–20. London and New York: Routledge.

- Bhambra, G. K. 2014. Postcolonial and decolonial dialogues. Postcolonial Studies 17 (2):115–21. doi: 10.1080/13688790.2014.966414.

- Bledsoe, A., and W. J. Wright. 2019. The anti-blackness of global capital. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 37 (1):8–26. doi: 10.1177/0263775818805102.

- Bosworth, K. 2018. The people versus the pipeline: Energy infrastructure and liberal ideology in North American environmentalism. PhD diss., University of Minnesota. Accessed July 29, 2019. http://hdl.handle.net/11299/200225.