Abstract

Majority-Black cities in North America are not often described in the academic literature as such. Racial capitalism is a restorative approach that puts majority-Black cities in the Global North into analytical relation with other cities in the global urban landscape. This is an important step to take for many reasons, including rising interest in conversations about the financial production of urban natures in the context of climate change. Moreover, there is a dearth of mixed method empirics documenting the role of racial capitalism in the production of urban space and urban natures. To address this gap, I pair a case study of Jackson, Mississippi’s, struggle to fund mandated upgrades to its water system with analysis of a data set containing interest rates of approximately 5 million municipal bonds issued between 1970 and 2014. I find that since financial deregulation in 1999 and 2000, majority-Black cities have been charged more than their white counterparts to produce their built environments. These findings reveal a conflation between territorialized Blackness and financial risk. Thus exposed, I argue that the racialization of urban finance has previously unexamined implications for the production of urban natures and the establishment of just transitions and socioecological futures.

对于北美的黑人占多数城市, 学术文献常常不这样描述。种族资本主义是一种恢复性的方法, 在全球城市格局中, 将发达地区的黑人占多数城市与其它城市的关系设置为解析性的。由于诸多原因(包括在气候变化的背景下, 人们对城市的金融产物的对话越来越感兴趣), 这是重要的一步。此外, 还缺乏混合方法研究, 去描述种族资本主义在建造城市空间和城市特征中的作用。为了弥补这一差距, 本文结合了美国密西西比州杰克逊市为强制性供水系统升级提供资金的努力, 以及1970至2014年发行的约500万市政债券的利率数据。本文发现, 自1999年和2000年金融管制放宽以来, 黑人占多数城市比白人城市支付了更高的城市建设费用。这些发现, 揭示了属地化黑度和金融风险之间的结合。因此, 城市金融的种族化, 对建造城市环境、建立公平过渡和社会生态未来, 有未曾讨论过的意义。

Las ciudades de mayoría negra en América del Norte a menudo son descritas como tales en la literatura académica. El capitalismo racial es un enfoque restaurativo que coloca las ciudades de mayoría negra del Norte Global en una relación analítica con otras ciudades del paisaje urbano global. Dar este paso es importante por muchas razones, que incluyen el interés creciente en las conversaciones acerca de la producción financiada de naturalezas urbanas en el contexto del cambio climático. Aún más, hay una escasez de empirismo en métodos mixtos que documenten el papel del capitalismo racial en la producción de espacio urbano y naturalezas urbanas. Para abocar esta brecha, yo emparejo el estudio de caso de la lucha de Jackson, Mississippi, para financiar la renovación ordenada de su sistema hídrico con el análisis de un conjunto de datos que contiene las tasas de interés de aproximadamente 5 millones de bonos municipales expedidos entre 1970 y 2014. Descubro que desde la desregulación financiera de 1999 y 2000, para llevar a cabo sus entornos construidos las ciudades de mayoría negra han tenido que pagar más que sus contrapartes blancas. Estos descubrimientos revelan una suerte de fusión entre negritud territorializada y riesgo financiero. Expuesto el asunto de esa manera, sostengo que la racialización de la financiación urbana tiene implicaciones no examinadas anteriormente para la producción de naturalezas urbanas, y el establecimiento de transiciones justas y futuros socioecológicos.

In nearly every U.S. capital there exists a tension between state lawmakers and the city government tasked with providing the free municipal services and utilities rendered to capitol buildings.Footnote1 This tension is especially high in the capital city of Jackson, Mississippi, a working-class, majority-Black city that houses the legislative body for the state of Mississippi (Field notes 2014). Goings on in the capitol are notoriously insulated from life in the rest of the work-worn town, not only politically speaking but socially and emotionally as well. To speak plainly, the city of Jackson is not a favored child of the state of Mississippi. On occasion, however, events transpire to remind the Republican-dominated state legislature of the materiality of their disinvested location, such as the hard freeze that occurred overnight on 10 January 2010. The freeze led to more than 150 water main breaks in the city and the closure of public schools and most universities and businesses in the area for the better part of a week. It also happened to cut off water access in the capitol. Among Jacksonians, the moment state legislators no longer had access to running water themselves is largely considered to be the moment when the state of Mississippi finally acknowledged the capital city’s infrastructural disrepair and began to make it a government priority (Field notes 2015; Nave Citation2015a).

As the research trajectory of infrastructure and maintenance and repair studies (Mattern Citation2018; Knuth Citation2019; Silver Citation2019) has gathered speed in recent years, so, too, have inquiries into the nature of urban and ecological processes of racial capitalism (Pulido Citation2016; Ranganathan Citation2016; Roy Citation2017; Nik Citation2018; McElroy and Werth Citation2019), the sociospatial process of racialized value creation theorized by Robinson (Citation2000). At the same time, an increasing amount of scholarly attention is also being paid to understanding the connection between processes of racial capitalism and settler colonialism, particularly regarding how these coconstructed dynamics of empire play out in global cities (McKittrick Citation2013; Roy Citation2017; Danewid Citation2020). Yet as McElroy and Werth (Citation2019) noted, there is also a growing need to understand how these global processes of empire unfold in places falling outside the global city hierarchy. Within a multicultural settler society, the “domestic space of empire” (Danewid Citation2020) expresses many different forms and flows of raced space. Racial concentration, isolation, and displacement happen at different scales simultaneously, with scholars increasingly aware that these seemingly contradictory flows of people, wealth, property, and environmental impacts are intimately bound together through racialized processes of value production under racial capitalism. Racial banishment (Roy Citation2017), or the violent displacement of raced and classed groups of people from the heart of a city, might be the most prevalent process within the scope of the global city, but when one considers the broader regional contexts within which these global cities are embedded, we see other patterns emerging alongside racial banishment. Historically over the past half-century, the strongest of these counter—yet coeval—currents has been the formation and reproduction of the majority-Black city.

In line with Roy’s (Citation2018) argument that the “South is not a location” but a “structural relation of space, power, and knowledge produced and maintained in the crucible of racial capitalism on a global scale,” (as cited in McElroy and Werth Citation2019, 882) this article contributes an alternative lens to understanding the global urban, one premised on the contemporary financial experience of some of the largest Black-majority cities in North America. Even though these large cities are located in the heartland of the Global North, none of them qualify as global cities, traditionally defined (Sassen Citation2005) as urban agglomerations of capital, information, and infrastructure that act as crucial nodes in the world economy. Although local growth machine coalitions (Molotch Citation1976) within each of them might profess global city aspirations, these cities are sites for global capital extraction more so than concentration. In line with Bledsoe and Wright’s (Citation2019) missive that critical scholarship must “push further to explicate the ways in which capitalism is actually dependent on anti-Blackness to realize itself” (4, italics in original), I seek to complement existing analyses of racial capitalism and empire-making in global cities by focusing on how these dynamics are both ecologically and financially reproduced outside the global city network. I do so through an investigation into the municipal indebtedness of the twenty-one largest majority-Black cities in the United States, with a particular emphasis on the financial costs of infrastructural repair related to federally mandated sustainability efforts in the capital city of Jackson, Mississippi.

The next section establishes majority-Black cities in the United States as a historical phenomenon that has taken on new relational significance in the contemporary moment of debt-financed urban development. I then go on to make clear the implications of the relationship between (anti-)Blackness, municipal finance, infrastructural maintenance, and empire by engaging two of the most influential streams of political ecology—climate justice and green finance—using McKittrick’s (Citation2013) lens of plantation futures to read across them. For McKittrick, the sociospatial configuration of the plantation is what links past and present forms of anti-Black violence to one another. I suggest here that plantation spatialities are also what financially and ecologically connect majority-Black cities to the rest of the global city hierarchy. I then qualitatively show how this works in the case of a municipal bond issuance by the city of Jackson for infrastructural repairs related to environmentally upgrading its water system, and then I do so quantitatively, using the annual median interest rates obtained in the municipal bond market by the twenty-one largest majority-Black cities in the United States as compared to all other U.S. cities from 1970 through 2014. I conclude with a discussion on the implications of the findings for the production of just urban futures.

Situating Indebted Majority-Black Cities

According to Harshbarger and Perry (Citation2019), the number of majority-Black census-designated places in the United States, including large cities and small towns with a minimum population threshold of 2,500, totaled 460 in 1970 and grew to 1,148 by 2010. They related, however, that the total Black population of the United States only grew by 1.5 percent, from 11.1 percent to 12.6 percent during those same years. This means that the growth of these majority-Black towns lay in demographic trends occurring not only within cities but between them as well. By far, the strongest of the demographic trends contributing to the contemporary production of majority-Black urban spaces has been white flight. Although it might be taught as such in the classroom, white flight is certainly not a relic of the past. Birmingham, Alabama, was only 42 percent Black in 1970 and 73 percent Black in 2010, for example (Harshbarger and Perry Citation2019). According to my own calculations, to be presented shortly, in 2014 there were twenty-one majority-Black cities in the United States with total populations over 100,000.

Confronting the sorts of structural dynamics that have the power to perpetuate processes of white flight in some cities while producing violent forms of racial banishment in others is impossible to do without a relational theory of racial capitalism operating on a world scale. In some important ways the concept of racial capitalism is itself a product of relational comparison, as Robinson and others working in the same vein (e.g., W. E. B DuBois and C. L. R. James) were at pains to show precisely how received historical views and theories were themselves distorted by processes of racialization. In a similar spirit, in dealing with a city located in a state still deeply caught in the trappings of its antebellum past, as Mississippi is, I turn to relational comparison (Hart Citation2018) to defend against static and unproductive declarations of local or regional exceptionalism. Jackson, for example, is not the only, or even the first, Black-majority city to become heavily indebted on the municipal bond market through attempts to finance repairs to its water system. In 2011, at the height of the economic downturn caused by the global financial crisis of 2008, Jefferson County, Alabama, the county encompassing the majority-Black city of Birmingham, filed the largest municipal bankruptcy in U.S. history up to that point. It was forced to do so after the state government struck down a crucial payroll tax, making it impossible for the county to service more than $3 billion in predatory loans issued for federally mandated water system repairs (Taibbi Citation2010; Ponder Citation2018). Just two years later, however, in 2014, Black-majority Detroit, Michigan, a city much closer to Canada than the Mason–Dixon line, broke that record, making headlines for its $18 billion bankruptcy, $6 billion of which was comprised of predatory debt accumulated by the city’s water system in attempts to fund federally mandated repairs. Moreover, Detroit bankruptcy judge Steven Rhodes and emergency manager Kevyn Orr refused to restructure that part of the city’s debt, opting instead to allow for the restructuring of the water department itself, so that surrounding white-majority suburbs were given a majority stake in one of the largest public assets of the largest majority-Black city in the country (Phinney Citation2018; Ponder and Omstedt Citation2019).

One of urban and economic geography’s principal theoretical contributions of the last several decades has been to highlight regional variability in the adoption of global processes such as neoliberalism and financialization. Although the same dynamic of differential regional implementation certainly also holds true for racial capitalism, I have found this understanding to be underrepresented within the spectrum of reactions I have received when presenting my findings to various audiences over the past several years. Admittedly this might be due to my own shortcomings as a presenter, but people have rather appeared to hone in on the explanatory power of the locational aspect alone, sometimes memorably invoking Nina Simone’s powerful civil rights anthem “Mississippi Goddam”—my understanding being that in doing so people not only expected but believed it inevitable to find anti-Blackness made starkly manifest in this particular place much more so than elsewhere. In line with Roy (Citation2018) and Hart (Citation2018), however, this project is about understanding the ubiquity of anti-Blackness not only within but beyond the U.S. South: It is about honoring the experience Simone captured in her song and building on it by situating Jackson and other majority-Black cities within “a world of many Souths” (Byrd 2014, as cited in Roy et al. Citation2020). Understanding the pervasiveness of anti-Blackness in the financial and ecological production of urban difference as a locally experienced aspect of global racial capitalism rather than of regional exceptionalism is thus a central analytical tension of this article. The next section retains this concern for relationality as it considers the treatment of racialization in the literature surrounding the production of urban natures.

Locating Plantation Futures in Global Urban Landscapes

Two of the most influential streams of contemporary political ecology at the moment are studies related to understanding urban geographies of environmental and climate justice (Pulido Citation2016; Heynen Citation2018; Routledge, Cumbers, and Derickson Citation2018; Ranganathan and Bratman Citation2019) and studies concerned with understanding the role that finance plays in various “green capitalism” strategies (Castree and Christophers Citation2015; Johnson Citation2015; Ekers and Prudham Citation2017; Kay Citation2018; Dempsey and Bigger Citation2019; Knuth Citation2019). Although the two approaches are both centrally concerned with interrogating (and improving) tactics of environmental sustainability, they appear to be epistemologically operating independently of one another, mirroring the political–economic division between their respective empirical subjects: stakeholders of environmental and climate justice movements versus the institutional agents and beneficiaries of “green” economic development. The green finance literature largely focuses on examining the fragility and frequent misalignment of market-based mechanisms with their stated social or environmental goals, whereas the literature on climate justice is focused on placing the lived experience of frontline communities in the context of the long durée of racial capitalism. Both streams have important contributions to make for the other.

Empirically, green finance studies often—although not exclusively (e.g., Knuth Citation2019)—focus on economic and financial development schemes that take place in the Global South, albeit governed and monitored by financial institutions rooted in the Global North, whereas the climate justice literature is broadly focused on the experience of communities of color in the Global North. A small but growing group of exceptions to this trend include Ranganathan (Citation2019), who compared questions of climate justice in Flint and Bangalore through the lens of property relations, and Bigger and Millington (Citation2019), who compared the use of green bonds in New York City and Capetown. Despite these exciting contributions, there remains a deep epistemological separation between the two sets of literature in their inverse focus on understanding the constitutive roles of racialization and finance in questions of climate change adaptation and resilience. For the most part, the climate justice literature has not been particularly focused on understanding the role of finance as it affects environmental and climate justice efforts (Pulido’s [Citation2016] hallmark piece on Flint, Michigan, excepted). At the same time, the green finance literature has not been particularly focused on understanding the role of racialization as it has informed the creation and application of climate finance technologies. Understanding how political ecology concerns and their financial solutions have been fundamentally shaped through racial structures and racialized outcomes of previous processes of capital creation is a gap in both sets of literature and thus remains a pressing challenge. Interrogating the financial production of Black urban natures is a useful lens for understanding these connections; it has the capacity to show us not only how urban political ecology has become enrolled in racial capitalism but how it has come to play a formative role in the progression of racial capitalism as a system of organization.

Leitner et al. (Citation2018) described the “top-down” mix of globally dominant firms, nongovernmental organizations, and philanthropic arms of corporations that have become preeminent forces in shaping economic and governance activities related to urban climate change as the “global urban resilience complex.” This complex is headquartered in the world’s global cities but also shows a strong predilection for initiating projects elsewhere. Importantly, this global complex is premised on the idea of the “resilience”—that is, the adaptability to, or quick recovery from, violent disturbances—of urban natures, having framed this desired characteristic of urban systems as a “marketable commodity that renders a Return on Investment” (Leitner et al. 2018, 1277, 1282). Leitner and colleagues critiqued this approach to urban resilience as exclusionary and implicitly antithetical to localized practices already taking shape in communities and climate justice movements around the world. Related, one of the most potent geographic imaginaries associated with the older global cities thesis is that the process of urban competition underlying the formation of globally powerful cities also implies the ongoing production of a world map wherein a “wealthy archipelago of city-regions” eventually becomes “surrounded by an impoverished Lumpenplanet” (Petrella Citation2006, cited in Brenner and Keil Citation2006, 194). Dystopic a vision as this might seem, it nevertheless contains important insights into the sorts of dynamics underpinning the relationship between world cities and the rest of the global urban landscape. World cities are increasingly seen not only as extracting labor and wealth from their surrounds but also in terms of their role in maintaining and reproducing colonial spatialities of domination (e.g., Roy Citation2017; Danewid Citation2020; McElroy and Werth Citation2019). This analytic becomes easier to perceive if we reverse the perspective of the preceding metaphor: If we look back at these urban islands of global wealth and power from the standpoint of the so-called Lumpenplanet or, more precisely, if we view them from the condition of Blackness and the Black experience, what becomes visible is the sociospatial formation of the plantation on a world scale. Rather than a mixed Marxian-maritime metaphor, global cities become legible as the “big houses” from which the dictates of a violent global socioeconomic order are institutionalized and carried out and to which dispossessed value accumulates from other dominated urban landscapes. Important for the purposes of this article, this includes proceeds garnered by the global urban resilience complex from elsewhere.

A similar conversation is being had in the environmental humanities around the notion of the Plantationocene, a description of what we currently call the Anthropocene that attributes our contemporary condition of environmental crisis to the violent socioecological rationalization that was accomplished through the racialized spatial ordering of the plantation (Davis et al. Citation2019). My goal in reading the climate justice and green finance literatures through the lens of McKittrick’s (Citation2013) plantation futures is to bring a similar inflection to conversations now underway in urban studies. To do this, I focus the rest of this article on illustrating the conflation of financialized risk and territorialized Blackness to suggest that majority-Black cities and their urban natures are a useful lens from which to understand how racial capitalism flows through both urban finance and urban resilience frameworks to spatialize plantation futures. The following sections present a mixed-methods analysis that points toward Black cities and Black urban natures—specifically in the form of urban infrastructures such as water systems—as extractive sites for transnational finance capital. The findings reveal that territorialized Blackness, by which I am here referring to majority-Black urban places with defined city limits and a generally high degree of Black city leadership, is translated by deregulated financial markets as inherently having a higher risk of default. These majority-Black places are thus operationalized by financial markets as spaces of increased potential for financial gain through the interest rate mechanism. This means that majority-Black cities in the United States are being categorically charged higher interest rates to produce their built environments than other cities are and have been at least since financial deregulation took place at the turn of the millennium. A case study into understanding how these higher interest rates are experienced on the ground reveals that cities like Jackson, Mississippi, are being charged exorbitant rates as they borrow to refurbish underfunded water systems, in their struggle to upgrade urban infrastructures and urban natures to more sustainable futures.

The next section presents an intensive look at the urban experience of Jackson, Mississippi, as it attempts to finance upgrading of its municipal water system—a crucial component of its built environment and foundational aspect of any city’s urban resilience capabilities. This is followed up by an extensive analysis of 4.9 million bonds issued to cities in the municipal bond market over the period from 1970 through 2014, which I provide to show that Jackson is far from being an exceptional case study but rather belongs to a categorical trend experienced by majority-Black cities in the United States. First, though, I briefly discuss methodological aspects of the work.

Methodological Considerations

There are two time periods under consideration in the study. In order of presentation, through document analysis of official statements of municipal bonds, federal white papers on energy savings performance contracts, local media coverage and other related documents; participant observation of Jackson city hall proceedings and related committee meetings; and semistructured interviews with water department officials, legal representation for the mayor of Jackson and the regional levee board, and affected residents and community activists, I first consider the city of Jackson from approximately 2011 onward. My starting point for this first half of the analysis is with the issuance of the municipal bond related to the upgrading of the city’s sewer and water system that began with those burst water pipes back in 2010. I use a qualitative, on-the-ground method of investigation to consider the often-invisible element of human connection in financialized processes of accumulation and social regulation. The aim here is to illustrate the sorts of social relationships and operational contexts that structure the production of racially extractive municipal bonds. Then, I broaden the scope of analysis to examine the relationship of the twenty-one largest majority-Black urban areas in the United States to the municipal bond market from 1970 through 2014. I selected the years under consideration to capture the moment of transformation from Keynesian to neoliberal logics to see whether there was any difference expressed between interest rates from those different modalities of economic organization, with the significance of these years also marking the rise of financialization.Footnote2

Finally, I want to note that I undertook field-work over the springs and summers of 2014 and 2015. These fieldwork episodes were tragically punctuated by the murders of Michael Brown by police in Ferguson, Missouri, in August 2014 and members of the Mother Emmanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church by a white supremacist in Charleston, South Carolina, in June 2015. This time period also marked the corollary rise of a reinvigorated form of liberatory Black political organization, producing the formation of the Black Lives Matter movement and associated collectives. I mention this here for two reasons: first, these geographically dispersed yet systemically related events are what motivated me to expand my analysis from Jackson alone to attempting a financial examination of every large majority-Black city the United States and, second, I mention this to avoid the intellectual tendency to compartmentalize sociospatial phenomena and study them as discrete issues. Black people in the United States are experiencing state violence in many forms simultaneously: from spectacular forms of police violence to the slow violence of defunded, undermaintained, and often toxic socionatural environments. Although I consider the ongoing financial exploitation of this latter form of violence in the pages that follow, it is important to keep in mind that the lived experience of each of them is simultaneous.

Spatializing the Municipal Bond Market

Establishing majority-Black cities as a category of analysis is an important step to take in developing understandings of how contemporary racialized capital moves through and operates at the urban scale. Moreover, the analytics of urban processes gathered from the experience of majority-Black cities are a useful way to sharpen urban theory more generally, for understanding the realities and relationalities of the systems of world cities, and especially with regard to clarifying the uneven production of urban natures between cities in the context of climate change. The fact, for example, that the two largest municipal bankruptcies in U.S. history were filed by majority-Black urban areas (Detroit, Michigan, and Jefferson County [Birmingham], Alabama) is not a coincidence but an effect of racialized extraction operationalized through financial capital. As previously mentioned, in both cities a key site of that financial extraction happened through their water departments, both of which were subject to federal consent decrees (a form of legal settlement in the United States) requiring them to environmentally upgrade their water and sewerage systems. These governments wound up owing approximately $5.7 billion (Detroit) and $3.3 billion (Jefferson County) on the municipal bond market due to the costs of these water system upgrades.Footnote3 The next section explains how a very similar experience has unfolded in Jackson.

Racing Resilience

Back in 2010, a coalition of elected leaders, lawyers, and high-ranking employees of the water department were negotiating a Clean Water Act consent decree with the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for the city’s sewerage system. At the same time, the transnational engineering firm Siemens, headquartered in Munich, Germany, and housed in a recently designed building described as a “flagship project of sustainable design in an urban context” (U.S. Green Building Council Citation2019) presented a proposal to audit Jackson’s water system for potential savings to be gained by implementing energy-efficiency procedures. Since the 1990s, U.S. cities with aging water systems have become legally entangled with EPA-enforced federal regulations aiming to make water systems more environmentally sensitive and energy efficient, and they face steep fines for remaining in violation of current national regulations. These efforts are tied to larger practices of sustainability and climate change mitigation efforts, and EPA consent decrees have become primary regulatory tactics to pursue this goal at the municipal level. Importantly, however, they remain unfunded mandates, meaning that the federal branch of the government is requiring the change but providing very little to zero substantive financial support to municipalities for actually undertaking the required changes. Similarly, recovering energy savings from aging municipal utility systems, like water and sewerage systems, has also become part of a national and global trend to address climate change. Jackson’s antiquated water billing system had been in place since 1972 (Lynch Citation2010), and the presence of federal consent decree negotiations made it obvious to relevant industry players that Jackson would need to begin costly, capital-intensive repairs sooner rather than later. For their part, city leaders hoped that the Siemens’ audit and proffered efficiency improvements would help to pay for the repairs required under the EPA’s unfunded mandate and avoid burdening residents with drastically increased utility bills. As part of their proposal, the engineering firm said it would charge Jackson for the audit only if the city council decided to contract with another company for the water system upgrades the audit recommended. This was a compelling offer for a working-class city like Jackson, where per capita income was $17,434 in 2013 (and rent expenses about half of that, averaging $720 per month).Footnote4 Unsurprising, the city agreed to go with Siemens for the repairs the audit suggested, and the company placed their local employee, former Mississippi State football star Chris McNeil (whose NFL draft stats can still be found on sports Web sites) in charge of handling the subsequent contract negotiations with the city council.

The promotion of energy savings performance contracts as a legitimate instrument of municipal finance also came from another trusted corner, the Mississippi Development Authority (MDA), established to help Mississippi municipalities locate funding for their infrastructural needs without exceeding their state-imposed debt limits.Footnote5 The MDA promoted energy performance contracting to its municipal constituents as “a method of making the energy upgrades you need now—with no up-front capital— and paying for them later through the energy savings that result from the retrofit of the facility … [and are] guaranteed by the Energy Service Company.”Footnote6 During the last month of local real estate mogul Leland Speed’s second tenure as executive director of the MDA, the Jackson city council agreed to the performance audit of its water system by Siemens. With subsequent assurances from hometown hero McNeil during the follow-up contract negotiations that savings from the project would start coming in “immediately” (Cleveland Citation2013), and with former Mayor Johnson assuring readers of a local newspaper that the MDA “gave the deal a green light before I signed the contract,” the Jackson city council voted five to two to enter into the “largest and perhaps most complicated construction contract the city has ever signed” (Nave Citation2015b).

The lawyer for the city at the time, Pieter Teeuwissen, said, however, that the city council only gave the contract to the legal department after it “had been approved by the governing authorities. … We looked at the deal, and while the deal was legal, it didn’t seem like a good business deal” (Nave Citation2015c). It was the stipulated monthly dispersal of the proceeds from the bond issuance to Siemens that was the key reason why the former director of Jackson’s Public Works Department, Kishia Powell, said that she would not have signed the Siemens performance contract had she been director at the time. “There were no specific milestones in the contract” regarding project goals that must be met by Siemens before acquiring payment. “It’s clear that the contract seems to be more beneficial to [Siemens] in that regard,” she said (Ganucheau Citation2014).

The monthly payments stipulated in the performance contract subsequently became embedded in the structure of the underlying bond that was being issued to pay for the project. Although the bond issuance and market offering process could have served as a backstop for instituting some sort of project oversight mechanism for the city of Jackson, to ensure payments to Siemens happened in line with adequate work performed by the company, this did not occur. Although the bond was issued to the city to finance an energy savings performance contract, it was not actually repayable from the anticipated yield of the project, which would have been the savings derived from increased energy efficiency. Rather, according to the bond’s official statement, the debt issued to pay the transnational engineering company for services rendered was repayable “solely from the gross revenues derived from the operation of the combined water and sewer system of the city” (Mississippi Development Bank Citation2013, 2). This meant that the bond was to be repaid by user fees at large rather than savings specifically derived from the new energy-efficiency upgrades, as the MDA had advertised would be the case on their Web site. Because the source of repayment was different from the bond’s purpose and source of expected income, the issuance process did not identify the lack of oversight management as a project risk. A $91 million bond was thus issued under the supervision of a number of local and national financial experts for a project with no built-in guarantees of work progress because the ultimate source of repayments was not attached to the risk of the undertaking.

Crucially, this guaranteed source of capital repayment ruptures the connection between project risk assessment and product design of the bond, creating new municipal geographies of moral hazard. Because underwriters of municipal debt are de facto guaranteed to recoup capital investments, and also because certain types of municipal securities investors are known to seek out high-yield (and therefore higher risk) bonds to invest in, the fiduciary integrity of bonded projects is not oriented to the municipality but to the bond market.Footnote7 Take, for example, the perspective presented by a comanager of the very successful Delaware National High-Yield Municipal Bond Fund, in his description of the sorts of municipal bonds the Fund seeks to invest in: “The fund’s universe is composed of revenue-based bonds that get dinged by credit-rating agencies for any number of reasons. ‘An example would be a hospital in a lower-income area,’ … ‘It might get a lower rating because of its location, but that doesn’t mean it’s going to default’” (Max Citation2015). This sort of place-based discrimination is not only taken for granted in the municipal bond market but is built into the market’s very conceptualization and operationalization of risk. In the hypothetical instance of the hospital in a low-income area, risk is understood to be the risk of the low-income city defaulting on its loan. The market perversely protects itself from this risk by charging the low-income area more for building a hospital there than it would to build the same hospital in a wealthier area. Firms like Delaware National have correctly identified these moralizing moments of market valuation, but they have exploited them as opportunities for increased profitability rather than bringing attention to their classed and racialized geographies. Conversely, in the scenario of Jackson’s performance contract with Siemens, the risk the project posed financially to the majority-Black city and its residents was not even legible as risk during the bond issuance process. The only risk considered in any detail during the construction and design of the Siemens performance contract bond was the risk of Jackson’s default taken on by lenders and investors, against which the city paid additional fees to purchase bond insurance from Assured Guarantee Municipal Corporation, one of the largest bond insurers in the market (Mississippi Development Bank Citation2013).

Put simply, bonded projects work for the bond market industry, not for cities. In the next section I present longitudinal findings from four decades of municipal bond data history to provide a comparative, macroscale picture of the effects this bond market–oriented conception of risk has had on the spatiality of urban finance in the United States.

A Market in Urban Vulnerability

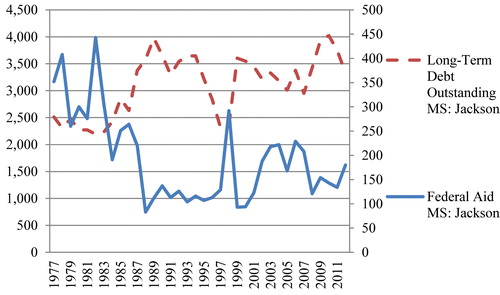

Before I get into the details of the bond data, I want to present a picture of the city-level relationship between federal aid and municipal debt. shows this relationship for the city of Jackson between the years 1977 and 2012. The amounts are in real 2012 dollars, with long-term debt outstanding on the left axis and rates of federal aid on the right axis. The two time series express nearly mirror images of each other, so that a decline in the amount of federal aid the city receives is almost always matched by a rise in the city’s long-term municipal debt load immediately thereafter, and vice versa. illustrates the powerful role played by the federal government in determining the level of financial vulnerability and exposure to investor-centered conceptions of risk that cities must face in the course of provisioning basic services to residents, as well as rehabilitating urban natures in the context of climate change.

Figure 1. Jackson, Mississippi: Long-term municipal debt versus federal aid, per capita. Source: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy (Citationn.d.).

In 2014 Jackson’s population was an estimated 80 percent African American with a median household income $20,000 less than the national median household income (U.S. Census Bureau Citation2016). The Siemens performance contract bond put these people on the hook for $203 million, with more than 55 percent of that total collected as interest on the $91 million principal loan amount (Mississippi Development Bank Citation2013). Whereas the median interest rate on all municipal bonds issued to cities in 2013 was 3.000 percent (Electronic Municipal Market Access [EMMA] data), the Siemens series has interest rates increasing annually from 5.000 percent to 6.750 percent throughout most of the maturity life of the series, ending in 2033. Then, after a seven-year reprieve, the bond picks back up again for a final $41,260,000 balloon payment at 6.875 percent interest (Mississippi Development Bank Citation2013).

It might, however, be argued that Jackson’s performance contract with Siemens was, in fact, correctly priced with a higher than average interest rate in the bond market precisely because it is a project with a higher than average risk and that the higher interest rates have nothing to do with Jackson’s poverty level, majority-Black population, or general economic vulnerability per se but with the characteristics of the performance contract. It could conceivably be argued that the interest rates on the Siemens performance contract bond in particular have been priced according to the characteristics of the bond, not the characteristics of the city.

A report put out by the U.S. General Accountability Office (GAO) in 2015 on energy performance savings contracts substantiates this argument to some extent. The report warned government entities (two years too late for Jackson) that “additional actions are needed to improve federal oversight” of these kinds of financial instruments and that even as far back as 2005 the GAO was aware that the federal agencies making use of energy savings performance contracts, which have been around since 1986, “often did not have the expertise and related information needed to effectively develop and negotiate the terms of ESPCs [Energy Savings Performance Contracts] and to monitor contract performance once energy conservation measures were installed” (U.S. GAO Citation2015, 2). So, theoretically, the higher than average interest rates on the Siemens performance contract bond could have been the product of market mechanisms accurately pricing an inherently risky contract. If this is the case, there is a clear argument here against actors in the municipal bond market and in the global urban resilience complex for withholding known information from cities on the dangers of a particular asset class in favor of obtaining higher yields associated with a harmful financial product. Be that as it may, however, data obtained on the past forty-four years of bond issuances for the largest majority-Black cities in the United States suggest that a much more systemic problem lies at the heart of the market.

Majority-Black Cities in Comparison

shows a list of the largest majority-Black cities in the United States and is derived from 2014 population estimates from the U.S. Census Bureau (Citation2016) for all cities with a population of over 100,000 in 2010, the year of the last official census. All cities with African American populations of 50.5 percent or more are included, resulting in a list of twenty-one contemporary majority-Black urban centers in the United States.

Table 1. Largest Black-majority cities in the United States by population

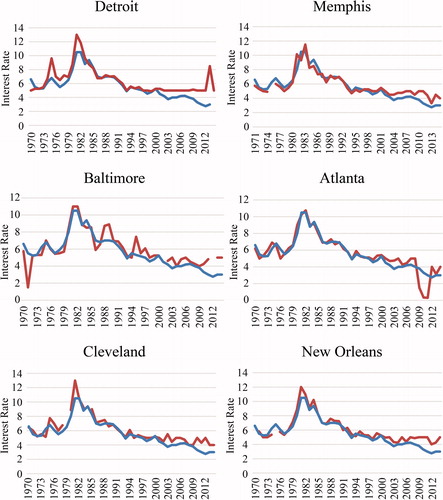

The first thing some might notice about this list is that most cities on it are located in the U.S. South, bringing to mind regional explanations for the different financial treatment of majority-Black cities. Demographically speaking, however, the South is where the majority of Black people in the country live (U.S. Census Bureau Citation2016). Notably, some historically majority-Black cities did not make the 2014 list, including Washington, DC, which narrowly fell below the threshold, and St. Louis, where the African American population is estimated to have fallen from 51 percent in 2010 to 48 percent four years later, in 2014 (U.S. Census Bureau Citation2016). African American populations of other majority-Black cities (e.g., Atlanta) are also facing displacement pressures as racial banishment through gentrification renders inner-city living desirable to the white and wealthy once again. I lay these demographic trends aside, however, to focus on the treatment in the municipal bond market of the twenty-one cities whose populations are currently estimated to be more than 50.5 percent Black. The following figures present data obtained from the EMMA Web site, a database of “virtually all municipal bonds” (Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board [MSRB] Electronic Municipal Market Access [EMMA] database Citationn.d.) that have been issued in the United States. It is maintained by the self-regulatory body, the Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board (MSRB), on behalf of investors, state and local governments, and other interested parties. I analyzed the interest rates of approximately 4.9 million bonds over the forty-four-year period from 1970 through 2014 to obtain these results. Although filing official statements and continuing disclosure documents is a legal obligation, it has only recently been (lightly) regulated as such. This often results in missing documents and subsequently missing data points. Even though the full data set consists of various pieces of information on 5.38 million bonds, just about 4.9 million bonds contain interest rate data. Nevertheless, this is the most consistently available variable for every bond in the data set. As such, it provides crucial information on the changing spatiality of the municipal bond market over time. The set of graphs in shows the median interest rate histories for the six largest majority-Black cities in the United States in 2014 (red line), in comparison with the median interest rate history for all municipal bond issues in the same year (blue line, which is the same in every graph).

Figure 2. Median interest rate, 1970 through 2014, for the six largest Black-majority cities. The red line indicates median interest rate for the city, and the blue line indicates the median interest rate for all bonds issued in the same year. Source: Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board (MSRB) Electronic Municipal Market Access (EMMA) database (Citationn.d.), author’s calculations.

One of the first noticeable things in the graphs is their shared peak, which is related to the interest rate spike occurring in the early 1980s, representing the effect of the “Volcker shock” on the municipal bond market. This interest rate shock occurred in all financial markets when then-Chairman of the Federal Reserve Paul Volcker drastically raised interest rates in an attempt to curb inflation. Also noticeable is that the overall interest rate environment has steadily declined in the years since then, from a high median interest rate of 10.50 percent for all bonds issued in 1981 and 1982 to a low of 2.75 percent for all bonds issued in 2012.

There are observable variations within each of the cities’ interest rate charts as well. The interest rates for Detroit and Memphis are historically very steady, rising and falling in a rhythm that is generally very close to the median rate for all municipal bonds. The third largest majority-Black city, Baltimore, has a much more volatile—and spottyFootnote8—interest rate trajectory over the same forty-four-year period. Atlanta, meanwhile, has for the most part stayed practically level with the median rate for all bond issues, with the exception of a very low dip during the years of the Great Recession. The majority of these very low-interest rate bonds appear to be where the city took advantage of the low-interest-rate environment to refinance older bonds that came to maturity during these years, or that were originally issued with higher interest rates. Cleveland and New Orleans display similar interest rate histories of small variations here and there along the median trend line.

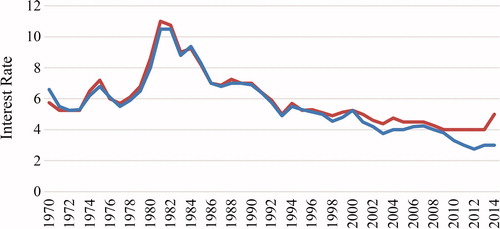

Significantly, however, each of these cities shares a major common element in their respective interest rate charts. Starting sometime between the mid- to late 1990s and the turn of the century, they each start to express interest rates that are, on the whole, systematically higher than the median interest rate for all bonds issued in the market in the same year. The figures for Detroit and Memphis display this trend most clearly, but it is present in the figures for each city. In fact, the tendency for majority-Black cities to obtain higher than average interest rates in the municipal bond market starting around the year 2000 is a categorical trend, as seen in , which displays the aggregate median interest rate history for all twenty-one majority-Black cities.

Figure 3. Median interest rate, 1970 through 2014, all issuers (blue) versus majority-Black city variable (red). The red line indicates median interest rate for the majority-Black city category, and the blue line indicates the median interest rate for all bonds issued in the same year. Source: Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board (MSRB) Electronic Municipal Market Access (EMMA) database (Citationn.d.), author’s calculations.

As shows, only once since 1998 have these twenty-one cities collectively received the average interest rate on their municipal bonds. As a group, the price charged to them for borrowing funds has only been lower than average seven times in the forty-four-year period under observation: four of them in the 1970s (1970, 1971, 1973, 1976), and two more times in the mid-1980s (1984 and just barely in 1985), and then for the last time in 1995, at a difference of one-tenth of 1 percent. The gap between majority-Black cities’ interest rates in the municipal bond market and other issuers started to increase in around 1996. The bursting of the dot-com bubble in 2000 is the only time since then that the median interest rates of the majority-Black city category matched those by all other issuers. Save for that one year, the aggregate majority-Black city interest rate has been systematically higher than average since the turn of the twenty-first century.

What happened around the year 2000 to effect such a clear change in the costs of production of urban space and urban natures for this group of cities? Why did majority-Black cities systematically begin to receive higher than average interest rates for their municipal bonds at this time in particular? The dynamics of their respective economies were not homogenous. Yes, some of them—for instance, Detroit and Cleveland—were facing postindustrial decline, but they had been doing so for years already. Meanwhile, other majority-Black cities on the list, like Atlanta, were enjoying an economic boost from the housing bubble that would collapse eight years later. New Orleans was still five years away from Hurricane Katrina.

Aside from their common denominator of having majority-Black populations, the other significant factor involved in the rising costs of borrowing money for these cities was the repeal of Depression-era legislation preventing investment banks from underwriting municipal revenue bonds. Previously, the Federal Reserve restricted member banks to underwriting only general obligation bonds that were backed by the taxing powers of the city and had to be passed by the city’s electorate. Under the Gramm–Leach–Bliley Financial Modernization Act of 1999, however, the ban was lifted and commercial banks became able to participate in the far larger market in revenue bonds, which bypass the voter approval process yet are, in most cases, still backed by a guaranteed source of payments in the form of user fees for essential services, just as Jackson’s performance contract bond guaranteed repayment from water system user fees. Meanwhile, the Commodity Futures Modernization Act of 2000 further enabled derivatives trading and instruments like credit default obligations and “swaptions” to enter the municipal bond market, entrenching contradictory incentives to simultaneously invest in and bet against financially exposed, economically vulnerable cities in the search for higher yield (Ashton Citation2009; Newman Citation2009).

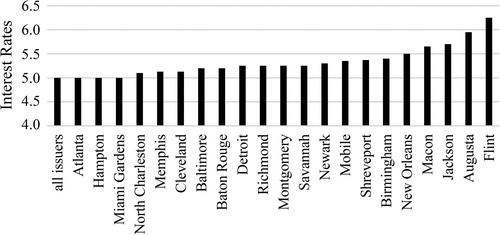

It is now, as public finance expert Sgouros (Citation2015) said, “crystal clear that in many ways, banks regard our state and local governments as marks to whom they can sell the newest, shiniest financial gimmick, no matter how risky or rigged” (101). For a closer perspective on city-specific variations within this category, shows the median interest rate acquired by each of the twenty-one largest majority-Black cities over the period between 1970 and 2014.

Figure 4. Individual median interest rates for largest majority-Black cities. Source: Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board (MSRB) Electronic Municipal Market Access (EMMA) database (Citationn.d.), author’s calculations.

Here we can see that three of the cities under analysis—Atlanta, Hampton, and Miami Gardens—achieved the same median interest rate of 5 percent as all issuers combined over this time period. Regarding Atlanta, in at least one way this makes sense, because it could be considered a reflection of its historically strong economy. In fact, between the years 1980 and 2013 the city was the country’s fastest growing metropolitan region, with a population increase of 136 percent (Cox Citation2015). Indeed, between these years Atlanta was “the fastest-growing city with a population of more than 5 million in the high-income world” (Cox Citation2015). Given Atlanta’s unprecedented growth, it is surprising, then, that the city’s ascribed interest rates only match the median rate for all other issuers. One would expect underwriters to assess a sustained twenty-three-year period of urban economic prosperity in a more positive light and assign lower than average interest rates for such a success story. For its part, Hampton, Virginia, belongs to a seven-municipality metropolitan region, Hampton Roads, which often issues municipal bonds as a single unit. Langley Air Force Base is also located there, which lends a high degree of economic stability to the area. Miami Gardens, a community just north of Miami, Florida, previously the home of African American teen Trayvon Martin, whose murder in 2014 prefigured the rise of Black Lives Matter, was only recently incorporated in 2003. In fact, according to the bond records found on EMMA, the city has only issued municipal bonds in two years under study—2010 and 2014, when the median interest rate for all issuers was 3.3 percent and 3.0 percent, respectively—thus making its median interest rate of 5.0 percent for those same two years far higher in comparison. Finally, with this chart we see that Flint, Michigan—infamous for its encounter with a lead-tainted water system while under antidemocratic emergency managementFootnote9—is the city with the highest median interest rate for this forty-four-year period, at an average of 6.25 percent. Jackson, Mississippi, follows with the third highest median interest rate of 5.70 percent.

Surviving Urban Resilience under Racial Capitalism

One of the tragedies of the Siemens performance contract is that city leaders entered into the deal because they thought it would protect impoverished residents of Jackson from exposure to extreme water bill hikes—they did it because they thought it would help. “You know, Jackson needs so much, and I thought this was going to be a way to help,” said a former member of the city council who voted in favor of the contract (Nave Citation2015c). The real tragedy of the Siemens performance contract, however, is the legacy of enduring indebtedness left to the inheritors of the city, its next generation. As the city struggled with financial problems stemming from the Siemens deal over the next three years, officials finally decided to file a lawsuit against the transnational engineering firm on 11 June 2019. The lawsuit charges the U.S. and German branches of Siemens with conducting “massive fraud” against the city of Jackson, specifically naming local representative Chris McNeil among the accused as well (City of Jackson, Plaintiff v. Siemens Industry Inc. Citation2019). In November 2019, the scope of the lawsuit was further increased, bringing the amount the city is seeking in damages up to $450 million, which encompasses the costs of funding the project, lost revenue from the Siemens installed system, and costs involved in stabilizing and managing the faulty system (Vicory Citation2019). By filing this lawsuit, Jackson has joined the growing ranks of cities choosing to litigate against their exploitative mistreatment in the municipal bond market, including Baltimore, Cleveland, Philadelphia, and Miami, among others (Egelko Citation2017). This type of litigation is not always successful, however, nor does it typically lead to permanent rule changes in the municipal finance industry. Moreover, the private banking system continues to be the only means by which these cities are able to access capital in the amounts necessary to continue providing the public services urban residents need, not least including urban sustainability efforts to combat climate change.

The findings of this research indicate that the U.S. municipal bond market is actively enrolled in the production of plantation spatialities within the global urban system. One of the ways this can be seen is through the interest rate histories and experiences of Black-majority cities issuing debt on this market, and particularly through Jackson’s experience attempting to finance the upgrading of its aging water system. The financial production of Black urban natures, as seen through the shared experience of upgrading water systems in Birmingham, Detroit, and now Jackson, further highlights how urban political ecologies are becoming financially operationalized under racial capitalism: through the construction of extractive flows of debt from Black cities and their residents, to investment institutions and other major players in the global resilience complex headquartered in the heartland of world city hierarchies. Cotton may no longer be king, but the sociospatial relation of the plantation remains with us under modern configurations of urban development and resilience financing.

Yet modalities of survival and resistance persist. Predatory subprime mortgages and the subsequent foreclosure crisis have given rise to a reinvigorated form of housing politics and tenant activism from below, and the predatory treatment of Black cities by municipal financial actors has given rise not only to this new wave of litigation by cities against banks but also to new forms of community-based, research-driven activism in the realm of municipal finance. The Action Center on Race & the Economy (ACRE) is one of the leading examples of these new forms of municipal actors. ACRE provides research and communications support for community organizations working “at the intersection of racial justice and Wall Street accountability” (ACRE n.d.). They are engaged in researching the relationship between the municipal finance system and public budget distress and have active and ongoing research interests in understanding the wealth-stripping activities of Wells Fargo in communities of color and the role of municipal finance in police brutality lawsuits.

In closing, this research shows that territorialized Blackness becomes differently harnessed by racial capitalism depending on whether Black places have become ensnared by, or cast out of, the global city. In this article I have highlighted how this happens in the presence of historical processes of white flight and the creation of majority-Black cities, but the relationship between racial banishment and white flight is, of course, ultimately much more complex than the confines of this article allow for and deserves further query. The case of Jackson and its energy savings performance contract additionally shows us that the municipal financial mechanisms developed to address urban infrastructural issues related to questions of resilience are not always, or even often, in the best interests of the majority-Black city, even if the products they finance do advance environmental sustainability. The contradictory interests exhibited by the white state apparatus, who endorsed the exploitative performance contract, and the majority-Black city who paid for it further demonstrates the assertion of Roy and others (cf. Hunter and Robinson Citation2018) that the (Global) South is not a location but a relational geography of racial capitalism. Similarly, the historical interest rate data show us that neither financial markets nor their state regulators can be trusted to develop racially just mechanisms to address the financial needs of cities facing the task of preparing for climate change.

This research reveals an extractive relationship between majority-Black cities and the global urban system. It shows that major players within the urban resilience industry, like Siemens, are similarly dependent on extractive methods of encounter with these cities and, finally, that the municipal financial system as currently designed does not support the equitable or just development of Black cities. This racialization of urban finance has profound implications for the immediate and long-term production of sustainable and just urban futures. It certainly points to the need for an urgent reevaluation of progressive political platforms that call for greater state involvement in financing urban resilience strategies. If finance is to play a major role in bringing about a more just socioecological transition to a warmer world, then understanding the racialization of urban finance, as demonstrated here, is an urgent task.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Adam Bledsoe, Sophie Webber, and Willie Wright for their thoughtful feedback on previous drafts and to editor Kendra Strauss and two peer reviewers for the care this article has received under their guidance. My thanks also go to Elvin Wyly and Jamie Peck for reading the many iterations of this work that have crossed their desks over the years. Finally, I express my gratitude to the people of Jackson.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

CS Ponder

CS PONDER is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Geography at Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL 32306. E-mail: [email protected]. She is also an Urban Studies Foundation Fellow with the University of Minnesota, Department of Geography, Environment & Society. Her research is concerned with understanding the racialization of urban finance and the implications for environmental justice.

Notes

1 Federally owned property is not subject to any local tax, which means that capital cities foot the bill for services required by state capitol buildings, such as infrastructural and service costs associated with providing water, electricity, and a police presence by request.

2 I collected the data from the EMMA database. One potential limitation of this portion of the findings is that despite its nature as a federally mandated compiler of public records on municipal bond issuance, EMMA has since changed its terms of use subsequent to my gathering this data in 2013 and 2014, so further analyses might prove hard to do because the data are now significantly more difficult and expensive to access.

3 In total, out of the nine largest municipal bankruptcies in U.S. history (not including Puerto Rico), cities with either Black- or Latinx-majority populations are involved in at least six of them. That list includes, chronologically: Vallejo, California (May 2009); Prichard, Alabama (October 2009); Central Falls, Rhode Island (August 2011); Jefferson County (Birmingham), Alabama (November 2011); Stockton, California (June 2012); San Bernadino, California (August 2012); and Detroit, Michigan (July 2013) The population of Vallejo, California, is more accurately described as a plurality, which is why I count the number of cities at six out of nine rather than seven.

4 Data obtained from city-data.com (Citationn.d.).

5 Authorities are state entities originally created during the Great Depression to route low-cost Public Works Administration loans from the federal government to localities without triggering the municipalities’ state-imposed debt limits. These limits were instituted in the late nineteenth century after the Panic of 1873 sparked a wave of municipal bond defaults taken out for railroad construction. Today, authorities are used for a number of economic development and service provision functions from housing to electricity to enticing major firms to relocate—and for the same purpose of avoiding debt limits, as well as avoiding the burden of voter approval for bond issuances (Sbragia Citation1996).

6 I take this quote from Nave (Citation2015b), because the Authority has since changed the wording on their Web site to “Energy Performance Contracting is an innovative financing package that uses savings from reduced energy consumption to repay the cost of installing energy conservation measures. A qualified Energy Service Company, or ESCO, guarantees a level of energy savings for a specified contract term sufficient to cover all project costs” (Mississippi Development Authority Citation2017).

7 Although the municipal bond market is known for its safe investing environment and practices, a minority of very active investors in recent years have often displayed higher risk-taking behavior of the sort described here.

8 The occasional missing value in these charts indicates that no bond information was available for the city for that year. This could mean either that the city issued no bonds that year or that the information and associated documents were not registered with EMMA or the MSRB as required.

9 My intent in pointing out the connection with Trayvon Martin and Miami Gardens and reminding people about Flint’s experience with a lead-contaminated municipal water system is not to sensationalize these moments of violence against Black life or to flatten the characterization of these complex, dynamic majority-Black cities to moments of death but to highlight the simultaneity of multiple forms of violence that I mentioned earlier and to give a sense, for unfamiliar readers, of the interplay between the lived geography of these events and interest rate histories.

References

- Action Center on Race & the Economy. n.d. About. Accessed February 17, 2020. https://www.acrecampaigns.org/about.

- Alvarado, F. 2018a. State attorney, SEC close probes of Miami Gardens officials with no criminal charges or sanctions. Accessed February 17, 2020. https://www.floridabulldog.org/2018/10/state-attorney-sec-close-probes-miami-gardens/.

- Alvarado, F. 2018b. Where did the money go from Miami Gardens’ $60M bond issue? SEC wants to know. Miami Herald, February 13. Accessed February 17, 2020. https://www.miamiherald.com/news/local/community/miami-dade/miami-gardens/article199865469.html#storylink=cpy.

- Ashton, P. 2009. An appetite for yield: The anatomy of the subprime mortgage crisis. Environment and Planning A 41 (6):1420–41.

- Bigger, P., and N. Millington. 2020. Getting soaked? Climate crisis, adaptation finance, and racialized austerity. Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space 3 (3):601–23. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/2514848619876539.

- Bledsoe, A., and W. J. Wright. 2019. The anti-Blackness of global capital. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 37 (1):8–26. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775818805102.

- BondView. n.d.-a. LOUISIANA LOC GOVT BATON ROUGE STUDENT HSG-SER A, 5.25%, 09/01/2035. Accessed February 17, 2020. https://www.bondview.com/bonds/defaulted/546279RK8.

- BondView. n.d.-b. MEMPHIS TENN HEALTH EDL & HSG FAC BRD MULTIFAMILY HSG REV TMG MEMPHIS APT PROJS-A, 5.75%, 04/01/2042. Accessed February 17, 2020. https://www.bondview.com/bonds/defaulted/586169CX0.

- Brenner, N., and Keil, R. 2006. The global cities reader. Philadelphia: Routledge.

- Castree, N., and B. Christophers. 2015. Banking spatially on the future: Capital switching, infrastructure, and the ecological fix. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 105 (2):378–86. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/00045608.2014.985622.

- City-data.com. n.d. Jackson Mississippi. Accessed September 18, 2016. http://www.city-data.com/city/Jackson-Mississippi.html

- City of Jackson, Plaintiff v. Siemens Industry Inc. Siemens AG, Chris McNeil, US Consolidated, Inc., US Consolidated Group LLC, M.A.C. and Associates, Ivision IT Consultants LLC, Garrett Enterprises Consolidated Inc., and John Does 1-10, Defendants. 2019. Circuit Court First Judicial District Hinds County, Mississippi. June 11. Accessed February 4, 2021. https://jacksonfreepress.media.clients.ellingtoncms.com/news/documents/2019/06/11/CityofJackson_v_Siemens_Et_Al.pdf

- Cleveland, T. 2013. Lumumba wants more Siemens oversight. Jackson Free Press, December 18.

- Cox, W. 2015. Can Atlanta heat up again? City-Journal Spring. https://www.city-journal.org/html/can-atlanta-heat-again-13720.html.

- Danewid, I. 2020. The fire this time: Grenfell, racial capitalism and the urbanisation of empire. European Journal of International Relations 26 (1):289–313. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066119858388

- Davis, J., A. A. Moulton, L. Van Sant, and B. Williams. 2019. Anthropocene, capitalocene, … Plantationocene? A manifesto for ecological justice in an age of global crises. Geography Compass 13 (5):e12438. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12438.

- Dempsey, J., and P. Bigger. 2019. Intimate mediations of for-profit conservation finance: Waste, improvement, and accumulation. Antipode 51 (2):517–38. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12503.

- Egelko, B. 2017. Cities can sue banks for predatory lending, rules U.S. Supreme Court. Accessed February 17, 2020. https://www.governing.com/topics/finance/tns-cities-banks-scotus.html.

- Ekers, M., and S. Prudham. 2017. The metabolism of socioecological fixes: Capital switching, spatial fixes, and the production of nature. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 107 (6):1370–88. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2017.1309962.

- Ganucheau, A. 2014. Jackson official: Wouldn’t have signed water contract. Clarion-Ledger, December 25. Accessed February 5, 2021. https://www.clarionledger.com/story/news/2014/12/25/jackson-water-contract-siemens/20905895/

- Harshbarger, D., and A. M. Perry. 2019. The rise of Black-majority cities: Migration patterns since 1970 created new majorities in U.S. cities. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution. Accessed December 12, 2019. https://www.brookings.edu/research/the-rise-of-black-majority-cities/.

- Hart, G. 2018. Relational comparison revisited: Marxist postcolonial geographies in practice. Progress in Human Geography 42 (3):371–94. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132516681388.

- Heynen, N. 2018. Urban political ecology III: The feminist and queer century. Progress in Human Geography 42 (3):446–52. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132517693336.

- Hunter, M. A., and Z. F. Robinson. 2018. Chocolate cities: The Black map of American life. Oakland: University of California Press.

- Johnson, L. 2015. Catastrophic fixes: Cyclical devaluation and accumulation through climate change impacts. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 47 (12):2503–21. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X15594800.

- Kay, K. 2018. A hostile takeover of nature? Placing value in conservation finance. Antipode 50 (1):164–83. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12335.

- Knuth, S. 2019. Cities and planetary repair: The problem with climate retrofitting. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 51 (2):487–504. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X18793973.

- Leitner, H., E. Sheppard, S. Webber, and E. Colven. 2018. Globalizing urban resilience. Urban Geography 39 (8):1276–84. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2018.1446870.

- Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. n.d. Fiscally standardized cities database. Accessed May 15, 2017. http://datatoolkits.lincolninst.edu/subcenters/fiscally-standardized-cities/.

- Lynch, A. 2010. City defends fee hikes, lay-offs. Jackson Free Press, November 23.

- Mattern, S. 2018. Maintenance and care. Places Journal. Accessed December 10, 2019. https://placesjournal.org/article/maintenance-and-care/.

- Max, S. 2015. Fund manager seeks city projects with high-yielding bonds. Barron’s, May 2. Accessed February 4, 2021. https://www.barrons.com/articles/fund-manager-seeks-city-projects-with-high-yielding-bonds-1430532728

- McElroy, E., and A. Werth. 2019. Deracinated dispossessions: On the foreclosures of “gentrification” in Oakland, CA. Antipode 51 (3):878–98. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12528.

- McKittrick, K. 2013. Plantation futures. Small Axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism 17 (3):1–15. doi: https://doi.org/10.1215/07990537-2378892.

- Mississippi Development Authority. n.d. Energy incentives and programs. Accessed March 28, 2017. https://www.mississippi.org/home-page/our-advantages/incentives/energy-incentives-programs

- Mississippi Development Bank. 2013. Special Obligation Bond, Series 2013: City of Jackson, Mississippi Water and Sewer System Revenue Bond Project. Jackson: Mississippi Development Bank.

- Molotch, H. 1976. The city as a growth machine: Toward a political economy of place. American Journal of Sociology 82 (2):309–32. doi: https://doi.org/10.1086/226311.

- Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board. Electronic Municipal Market Access. n.d. Accessed November 1, 2014. https://emma.msrb.org/Home

- Nave, R. 2015a. Jackson: New Rankin County wastewater plant is unlawful. Jackson Free Press, February 11. Accessed February 4, 2021. https://www.jacksonfreepress.com/news/2015/feb/11/jackson-new-rankin-county-wastewater-plant-unlawfu

- Nave, R. 2015b. Troubled water, part I: Explaining Jackson’s $91 million Siemens contract. Jackson Free Press, March 11. Accessed February 5, 2021. https://www.jacksonfreepress.com/news/2015/mar/11/troubled-water-part-i-explaining-jacksons-91-milli/

- Nave, R. 2015c. Troubled water, part II: The origins of Jackson’s 91 million dollar Siemens contract. Jackson Free Press, April 1. Accessed February 5, 2021. https://www.jacksonfreepress.com/news/2015/apr/01/troubled-water-part-ii-origins-jacksons-91-million/

- Newman, K. 2009. Post-industrial Widgets: Capital flows and the production of the urban. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 33 (2):314–31.

- Nik, H. 2018. Toward an abolition ecology. Abolition: A Journal of Insurgent Politics 1:240–47. Accessed December 12, 2019. https://journal.abolitionjournal.org/index.php/abolition/article/view/49.

- Petrella, R. 2006. A global agora vs. gated-city regions. In The global cities reader, ed. N. Brenner and R. Keil,194–95. London and New York: Routledge.

- Phinney, S. 2018. Detroit’s municipal bankruptcy: Racialised geographies of austerity. New Political Economy 23 (5):609–26. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2017.1417371.

- Ponder, C. S. 2018. The difference a crisis makes: Environmental demands and disciplinary governance in the age of austerity. In Cities under austerity: Restructuring the U.S. metropolis, ed. M. Davidson and K. Ward, 77–102. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Ponder, C. S., and M. Omstedt. 2019. The violence of municipal debt: From interest rate swaps to racialized harm in the Detroit water crisis. Geoforum. Advance online publication. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.07.009.

- Pulido, L. 2016. Flint, environmental racism, and racial capitalism. Capitalism Nature Socialism 27 (3):1–16. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/10455752.2016.1213013.

- Ranganathan, M. 2016. Thinking with Flint: Racial liberalism and the roots of an American water tragedy. Capitalism Nature Socialism 27 (3):17–33. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/10455752.2016.1206583.

- Ranganathan, M. 2019. Property, pipes, and improvement. https://www.e-flux.com/architecture/liquid-utility/.

- Ranganathan, M., and E. Bratman. 2019. From urban resilience to abolitionist climate justice in Washington, DC. Antipode 53:115–37. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12555.

- Robinson, C. J. 2000. Black Marxism: The making of the Black radical tradition. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Routledge, P., A. Cumbers, and K. D. Derickson. 2018. States of just transition: Realising climate justice through and against the state. Geoforum 88:78–86. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.11.015.

- Roy, A. 2017. Dis/possessive collectivism: Property and personhood at city’s end. Geoforum 80:A1–A11. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2016.12.012.

- Roy, A. 2018. At the limits of urban theory: Racial banishment in the contemporary city. http://www.lse.ac.uk/lse-player?id=3990.

- Roy, A., W. J. Wright, Y. Al-Bulushi, and A. Bledsoe. 2020. “A world of many Souths”: (Anti)Blackness and historical difference in conversation with Ananya Roy. Urban Geography 41 (6):920–35. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2020.1807164.

- Sassen, S. 2005. The global city: Introducing a concept. Brown Journal of World Affairs 11 (2):27–43.

- Sbragia, A. M. 1996. Debt wish: Entrepreneurial cities, U.S. federalism, and economic development. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press. Accessed December 26, 2019. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/j.ctt6wrcgn.

- Sgouros, T. 2015. Predatory public finance. The Journal of Law in Society 17 (1):91–102.

- Sherman, T. 2015. Newark debt downgraded to junk bond status, as outlook on 6 N.J. cities turns negative. https://www.nj.com/news/2015/05/newark_debt_downgraded_to_junk_bond_status_as_outl.html.

- Silver, J. 2019. Decaying infrastructures in the post-industrial city: An urban political ecology of the U.S. pipeline crisis. Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/2514848619890513.

- Taibbi, M. 2010. Looting Main Street. Rolling Stone, March 31. https://www.rollingstone.com/politics/politics-news/looting-main-street-196661/.

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2011. 2010 Census shows Black population has highest concentration in the South. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/2010_census/cb11-cn185.html.

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2016. American fact finder. https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/index.xhtml.

- U.S. Government Accountability Office. 2015. Energy savings performance contracts: Additional actions needed to improve federal oversight. Washington, DC: U.S. General Accountability Office.

- U.S. Green Building Council. 2019. Greenbuild Europe 2018. Accessed December 23, 2019. https://www.usgbc.org/education/sessions/greenbuild-europe-2018/g01-new-siemens-hq-%E2%80%93-how-apply-dgnb-leed-simultaneously–0.

- Vicory, J. 2019. Jackson claims conspiracy, fraud: Lawsuit against Siemens grows to $450M. Clarion-Ledger, November 25.