Abstract

In this article, young trans people share their experiences of exhaustion and exhausting temporalities. Drawing on participatory research with young trans people aged fourteen to twenty-five in London and Scotland, I trace forces implicated in the spatial and bodily emergence and fixity of exhaustion in young trans people’s lives to the sociomaterialities, embodied practices, and architectures of many everyday spaces, alongside societal hostilities, as a set of forces that often (attempt to) erode their agency and contribute to their “out-of-placeness.” I also undertake a queer reconceptualizing of the condition that emphasizes the specificities of the bodies, subject positions, and spatial interactions of exhausted people. Crucially, this reconceptualization recognizes that experiencing and embodying exhaustion can, perhaps paradoxically, initiate and make possible myriad potentialities, complicating academic work that positions exhaustion as the removal of possibility. The article reflects on the radical flourishing of trans youth lives, spaces, solidarities, and euphoric experiences by exploring participants’ (re)making of resilient, resistive, and restorative subjectivities, embodiments, and spatialities within exhaustion’s spatial and temporal pervasiveness. By illuminating exhaustion’s nonlinear, messy, and prolonged temporalities, I observe that such temporalities constitute a function of lived exhaustion while paradoxically providing conditions for such empowering, expansive, and often queer and transspecific potentialities.

在本文中, 年轻的跨性别者分享了疲惫及其时间性的经历。本文对伦敦和苏格兰14岁至25岁跨性别青年开展了参与式研究。在跨性别青年的生活中, 空间和身体的出现和疲惫的固定性都受到某些作用的影响。这些作用可以追溯到社会敌对行为, 以及日常空间的社会物质性、具体行为和结构。这些作用经常(试图)侵蚀跨性别青年的能动性, 并导致这些青年的“去地方性”。我重新理解了身体的特殊性、主体的位置和疲惫人群的空间互动。重要的是, 这种重新理解认识到, 疲惫的经历和体现可能会触发各种潜能、并使得这些潜能成为可能。这种认识可能是自相矛盾的, 复杂化了疲惫会消除可能性的研究。疲惫具有时空普遍性。本研究的参与者(重新)塑造了主体性、体现性和空间性的坚韧、抵抗和恢复。本文反思了跨性别青年丰富的生活、空间、团结和愉悦体验。通过阐明疲惫的非线性、混乱和长时间性, 我认为, 这种时间性决定了生活中的疲惫。矛盾的是, 这种时间性反而为赋能式的、扩张性的、同性恋和跨性别的潜能提供了条件。

En este artículo, los jóvenes trans comparten sus experiencias en el agotamiento y las temporalidades agotadoras. A partir de investigación participativa con jóvenes trans de entre catorce y veinticinco años, en Londres y Escocia, rastreo las fuerzas implicadas en la emergencia y fijación espacial del agotamiento en las vidas de jóvenes trans hasta la sociomaterialidades, prácticas corpóreas y las arquitecturas de muchos espacios cotidianos, conjuntamente con las hostilidades sociales, como un conjunto de fuerzas que a menudo (intentan) erosionar su agencia y contribuyen a su “fuera de lugar”. Emprendo también una reconceptualización queer de la condición que enfatiza las especificidades de los cuerpos, posiciones de los sujetos y las interacciones espaciales de la gente agotada. Crucialmente, esta reconceptualización reconoce que experimentar y encarnar el agotamiento puede, quizás de manera paradójica, iniciar y posibilitar una miríada de potencialidades, complicando el trabajo académico que posiciona el agotamiento como la eliminación de la posibilidad. El artículo hace una reflexión sobre el florecimiento radical de las vidas juveniles, los espacios, solidaridades y experiencias eufóricas trans, explorando la (re)creación de subjetividades, encarnaciones y espacialidades resilientes, resolutivas y restauradoras por parte de los participantes dentro de la omnipresencia espacial y temporal del agotamiento. Iluminando las temporalidades no lineales, desordenadas y prolongadas del agotamiento, observo que tales temporalidades constituyen una función del agotamiento vivido mientras que paradójicamente proveen las condiciones para tales potencialidades empoderadoras, expansivas y a menudo queer y transespecíficas.

Palabras clave:

Introducing Young Trans People’s Exhaustion and its Temporalities

The biggest thing that lowers our quality of life is society’s reaction to us, especially hostile reactions. And even, they don’t have to be hostile, it can be the fact that we’re not financially [secure], we’re in a country [the United Kingdom], we’re in a situation where we need to pay for our health care and our transition, if trans people want to transition medically [because of waiting lists], cos there’s so many ways to be trans [that aren’t recognized by professionals]. So even things like financially not being able to pay for that, family not accepting you,… government not having laws to protect you. Even with Trump right now, he’s not trying to repeal laws, he’s not focusing on the small things. He literally right now wants to repeal the existence of trans people. So erm with all that going on… it’s not surprising [that we feel anxious] and… when you break it down psychologically, the acceptance of oursel[ves] it’s never [what causes] those issues.

–Karl (he/him, 22–25Footnote1)

Many young trans people are exhausted by their everyday surroundings and encounters. Their exhaustion—often borne from continually encountering a multiplicity of cisnormative or hostile forces that emerge and exert pressure from myriad spatiotemporal and sociopolitical scales, as Karl’s words illustrate—is a condition tangible in many of their stories. In this article, I explore how experiencing and embodying the nonlinear, indefinite, and slow temporalities emergent from such exhaustion can (re)create feelings of anticipatory exhaustion toward particular events or spaces. I also demonstrate that the constancy and temporal messiness through which trans youth encounter exhaustion exacerbates its felt and affective dimensions, drawing on their descriptions of how exhaustion sets in as they continually perform an inauthentic self, by living through “long day[s] of being what other people want you to be” (participant’s phrasing) that induce a weariness and a wearing away of many aspects of their everyday lives, including their bodily autonomy, selfhood, self-assurance, and well-being. I also visibilize exhaustion’s temporalities through reflection on participants’ experiences of extended periods of waiting. Crucially, I contest existing research that has both focused on societal exhaustion and universalized the experience of exhaustion rather than drawing out its varied intensities that are shaped and felt according to bodily and social differences, subject positions, and specificities.

Throughout this article, I trace forces implicated in the spatial and bodily emergence and fixity of exhaustion in young trans people’s lives to binary-gendered, cisnormative, and trans-hostile sociomaterialities and architectures of everyday spaces (see also Crawford Citation2015), and spatially reinforced embodied practices that often erode their agency. The pervasiveness of these affects and encounters of exclusion, marginality, and hostility contribute to what I term their out-of-placeness, a condition associated with feelings of spatial and temporal disjointedness (see also simpkins Citation2017), embodied and emotional dislocatedness, unease, discomfort, and disturbance. After queering exhaustion, engaging Sara Ahmed and Gilles Deleuze to better attend to the specific experiences of young trans individuals and communities, I demonstrate how exhaustion can be both embodied and experienced individually through its seepage into trans youth bodies and subject positions, and collectively held (and negotiated and resisted) within young trans communities and spaces.

My approach to exhaustion also examines how trans youth subjectivities are (re)made and potentialities are enabled when exhaustion is felt and embodied, highlighting participants’ individual and collective agency and their ability to develop or harness mechanisms of trans and queer joy, empowerment, and solidarity. I highlight young trans people’s stories that attest to their experience of exhaustion as a site of queer potentiality for orienting toward affirming futures, transing and queering space,Footnote2 and generating euphoric experiences within their individual current contexts and wider societal experiences. This repositioning allows me to both complicate academic work that positions exhaustion as the removal of possibility and begin tracing how young trans people’s resilience, resistance, and restoration practices, and “safe spaces” they create, access, and maintain (see, e.g., Goh Citation2018), demonstrate this paradox. Consequently, following scholars who reflect on uneven experiences of supposedly collective affects such as Tolia-Kelly (Citation2006, Citation2016, Citation2017), Ahmed (Citation2004), and Bissell (Citation2016), and those who explore how atmospheres can cohabit spaces (B. Anderson and Ash Citation2015), I contribute to affective geographies more broadly by emphasizing the inextricable links between individuals’ sociospatial encounters with affect and atmosphere and the nuances of their embodied experiences (including, here, anxiety and dysphoria) and intersectionally rendered subject positions, bodies, and communities. Meanwhile, my focus on exploring the minutiae of young trans people’s everyday lives responds to a relative lack of (although growing) attention paid to youth sexualities and gender diversities in children’s geographies (although see, e.g., Costello and Duncan Citation2006) and the limited presence of young trans lives and voices in queer and trans geographies (although see, e.g., Jenzen Citation2017; Rooke Citation2010a, Citation2010b).

As Karl’s earlier words attest, in the United Kingdom and indeed across much of the North Atlantic, young trans people’s exhaustion is often shaped by a backdrop of change to, and turmoil in, societal conditions and discursive hostility widely experienced by trans people (Jacques Citation2020; Todd Citation2020). In the United Kingdom, there has been a stagnation in advancing trans people’s legal rights (Todd Citation2020), and hate crimes against trans folk have risen sharply (Home Office of the UK Government Citation2021). The UK Government has abandoned proposals for trans rights made in its 2018 LGBT Action Plan (CitationUK Government Equalities Office 2018a; Lawrence and Taylor Citation2020), and plans to reform the pathologizing, intrusive, and exclusionary Gender Recognition Act 2004 have been largely dropped. Meanwhile, trans rights opponents and gender conservative voices have gained growing prominence and influence, and trans communities experience increasingly hostile “debate” around their everyday lives and existence in public space (Pearce, Erikainen, and Vincent Citation2020; Todd Citation2021) Data available from the National LGBT SurveyFootnote3 (NLGBTS; UK Government Equalities Office Citation2018b, Citation2018c; Todd Citation2020) demonstrate that trans liberation and equality in Britain is measurably behind that of many cisgender (cis) LGB+people (lesbian, gay, bisexual, and other cisgender people of minority sexualities). For example, 63.1 percent of trans and non-binary respondents reported their comfort being a lesbian, gay, bisexual, and/or trans (LGBT) person in the United Kingdom at three out of five or lower, compared to 41.0 percent of cis respondents. Meanwhile, 66.5 percent of trans respondents reported avoiding “being open about their gender identity for fear of a negative reaction from others,” including 44 percent within the home (rising to 50.1 percent of non-binary respondents), 65.7 percent in workplaces, and 67.8 percent in outdoor public spaces (UK Government Equalities Office Citation2018b, Citation2018c; Todd Citation2020). Trans health care inadequacies expose trans people in the United Kingdom to mental and physical health inequalities (Pearce Citation2018; Vincent Citation2018b; Gleeson and Hoad Citation2019), a situation that is vulnerable to worsening through growing waiting lists, halted services during the COVID-19 pandemic, lack of political intervention, and trans-hostile and gender conservative movements to limit health care offered to trans youth. Crucially, as Pearce, Moon, et al. (Citation2020) describe, there is a growing paradox in the interwoven hypervisibility and hypervulnerability that many trans people experience globally and with particular intensity in Britain. As Ahmed (Citation2019) notices, in the United Kingdom, “permission is constantly [given] for transphobic harassment, creating a hostile environment for trans people [who] are often positioned as strangers not only as ‘bodies out of place,’ but as threatening those who are ‘in place’.” As this article demonstrates, trans youth often bear this societal turbulence and hostility acutely. Indeed, this article sits alongside work that troubles a linear “getting better” narrative persistent around (young) LGBTQIA + folk: lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer, intersex, asexual/agender people, and people of other sexuality and gender minorities (Lawrence and Taylor Citation2020).

Among other contributions, this article feeds into an expanding “trans geographies” subfield advancing work around the lives of trans (and to a lesser extent), non-binary, genderqueer, and gender-diverse people (Browne, Nash, and Hines Citation2010; Hopkins Citation2020; March Citation2021; Todd Citation2021) that does not sit directly under the “geographies of sexualities” banner.Footnote4 Much of this work aids in establishing the exhausting contexts that many trans people experience globally (although less so beyond Europe and North America). For example, “trans geographies” work (predominantly distinct from geographies of sexualities literature) that this study engages most closely with and builds on has highlighted the marginalizing effects of everyday cisnormativity and its associated embodiments and affects (Doan Citation2010; G. Anderson Citation2019; Brice Citation2020; Todd Citation2021) and bodily surveillance, transphobia, exclusion, and resistance in spaces like public bathrooms (Bender-Baird Citation2016; Cavanagh Citation2018), carceral environments (Rosenberg and Oswin Citation2015), detention and asylum systems (DasGupta Citation2018, Citation2019), the classroom (DasGupta et al. Citation2021), urban and public spaces and sites of mobility (Di Pietro Citation2016; Lubitow et al. Citation2017; Sullivan Citation2018; Mearns, Bonner-Thompson, and Hopkins Citation2020), rural settings (Abelson Citation2016), the home (Marshall Citation2017; Andrucki and Kaplan Citation2018; Johnston Citation2018; Arun-Pina Citation2021), nightscapes (Misgav and Johnston Citation2014; Campkin and Marshall Citation2017), queer spaces (Nash Citation2011), educational spaces (Mearns, Bonner-Thompson, and Hopkins Citation2020; Arun-Pina Citation2021), and space-times of disaster (Gorman-Murray et al. Citation2018). Many of these publications, however, are focused on trans people’s experiences of spaces of exception rather than everyday or indeed explicitly trans spaces. Meanwhile, narrative geographies of trans lives have been explored through such contexts and methods as “coming out” experiences (Marques Citation2020), autoethnographies (Doan Citation2010; Brice Citation2020, Citation2021; Arun-Pina Citation2021), and participatory research (Rooke Citation2010a, Citation2010b), although few large-scale studies have conducted qualitative geographical research solely with trans people. This literature has adopted and developed a range of conceptual framings that emphasize how trans folk might experience such ways of being as (dis)belonging (Johnston Citation2018); embodiment, affect, and materiality (Jenzen Citation2017; Andrucki and Kaplan Citation2018; Todd Citation2021); liminality (March Citation2021); activisms, resistance, and explicitly trans spaces (Rooke Citation2010a; Brice Citation2020; Fernández Romero Citation2021; Nash and Browne Citation2021; Todd Citation2021), transmobilities (Lubitow et al. Citation2017); and power geometries (DasGupta et al. Citation2021). Crucially, through intersectional analyses, this work has demonstrated that many spaces and times of everyday life can, for many trans people, become exhausting environments, radiate exhausting affects, and stimulate bodily states associated with exhaustion. Further work is required, however, to expand on the full complexity, diversity, and specificity of trans lives—such as trans people’s experiences of multiple marginalities, joy, and gender euphoria—through geographical lenses (see also Todd Citation2021 for an in-depth discussion around the strengths and absences of existing trans geographies literature). In addition to working toward fulfilling this expansion, this research also constitutes one of the few pieces of geographical research to incorporate and reflect on the experiences of non-binary people and other folk who live beyond gender binaries (G. Anderson Citation2019; March Citation2021) and examine the nuances of recruiting, researching, and working with young trans people specifically. By developing a specific account of embodiments and temporalities of exhaustion from the perspective of young trans people in the UK, this article not only undertakes a reconceptualization of the condition, but also contributes a nuanced perspective around trans lives at this specific juncture wherein many trans folk experience both hostility and affirmation.

Participatory Research with Young Trans People

As an individual dedicated to the liberty and euphoria of trans youth, my research and this article springs from a larger geographical research project exploring what the everyday looks and feels like for young trans people, how their everyday experiences vary spatially and temporally, and how it might be possible to make these realities visible beyond solely marginal or traumatic representations. Crucially, in line with a wider movement to enhance social justice within research with trans people and marginalized folk more broadly (Pearce Citation2020), a key driver behind the research was to create spaces specifically for young trans people to (1) come together and spend time reflecting both on issues and stories they felt were important to them, and (2) experience space-times where their transness was celebrated and affirmed. Indeed, the article draws on participatory research conducted with trans youth aged fourteen to twenty-five in London, via a collaboration with national charity Gendered Intelligence (GI; see McNamara Citation2018), which supported the research with recruitment pathways (Todd and Doppelhofer Citation2021), advice, research spaces, and youth work support. A separate, smaller aspect was conducted in Scotland.Footnote5 Accounting for trans scholars’ critiques of cisgender (cis) academics’ approaches and practices for engaging trans people in researchFootnote6 and research wariness and fatigue many trans communities experience (Jourian and Nicolazzo Citation2017; Vincent Citation2018a, Citation2018b; Humphrey, Easpaig, and Fox Citation2020), my aim was to draw on participatory action research (PAR) method(ologie)s to (co)create research spaces with young people and their gatekeepers that allowed trans youth to place their voices and experiences at the fore and facilitate their partial direction of the research. Throughout, I centralized queer solidarities and focused on prioritizing participants’ desires for research engagement and social interaction. I continually sought feedback and input from participants on the direction of each subsequent research session through activities focused on participants’ ideas for future research foci such as participatory diagramming (involving collectively visually mapping potential research themes and modes of working for future research encounters), collective reflection (involving group discussion, roundtable story-sharing, and delegating discussion facilitation to participants to avoid my own voice dominating), and other “feed-forward” methods (e.g., final questions in interviews focused on identifying potential future research topics, and participants using cards to write and share their ideas for research engagement). The research proper did not focus solely on harm and misfortune narratives or hostile spaces, but instead offered participants opportunities to reflect on their everyday lived realities in empowering “safe spaces.” Working alongside a trans or queer youth worker, through my multifaceted role as researcher, “guest (co)facilitator,” ally, and safeguarder, I could maximize participants’ well-being within these sites and beyond.

Through core methodologies involving eleven creative workshops embedded in queer/trans “safe spaces” (those of GI and an LGBTQIA + charity in Scotland) and nineteen lengthy interview spaces, the research involved ninety-six participant engagements (several participants attended more than one research session). The research sessions were advertised through GI’s mailing lists and via youth workers mentioning the research in youth work sessions; young people could then sign up to attend research spaces (for an extended discussion about the research recruitment see Todd and Doppelhofer Citation2021). In creative workshops, I blended PAR methods with group and individual discussions and support from trans and queer youth workers to develop spaces “where other people get it” that allow “active participation” without excessive burden (Furman et al. Citation2019, 2), sites where participants could creatively and collaboratively project their voices and stories and—particularly crucially—meet and socialize with other trans youth. Each workshop had a loose, central theme to initially structure (but not limit) participants’ discussions and creative work, such as transport and getting around, “escapism,” and online spaces. Meanwhile, one-to-one sessions offered participants opportunities to share deeper biographical stories through both oral histories and in-depth reflections on particular moments, events, objects, and spaces important to them and their (past and imagined future) life trajectories. Exhaustion was not initially identified as a research question or topic but emerged organically through participants’ stories and creative contributions as an urgent and common theme. Participants were not asked directly about exhaustion unless they raised this term themselves.

Throughout, participants told multiple kinds of stories, including collective narratives built through story sharing and comparison with other trans youth in creative workshops, individual, in-depth stories across all research spaces, and visual and creative story representations. Certain stories focused on one event, others on an object, time, or space, while others traversed entire life histories. Some participants had already collated their stories through diaries, photographs, collections, artwork, and writings prior to (or specifically for) this research; others had not yet reflected on their intimate life histories or even considered why their stories were worth sharing. Some participants’ narratives were heard for the first time by another trans or queer person. Crucially, storytelling-focused methods gave participants opportunities “to turn the tables, to relate their story to others [and] celebrate and promote the history and experiences of their varied and constantly shifting community in their own words and images” (Valentine Citation2008, Citation2016, 4; Furman et al. Citation2019).

The following sections return to everyday exhaustions shared by participants, focusing on particularly common temporalities of exhaustion they articulated, namely constancy and onslaught and waiting and temporal unboundedness. I begin from the exhausted account of a young trans man, Adam.

Adam’s Story

I first met Adam (he/him, 18–21), a young trans gay man, at a two-day creative workshop exploring participants’ experiences of transport and “getting around.” The workshop was the first explicitly trans space Adam had attended. After engaging in creative group work around transness for the first time, Adam visibly projected growing ease and embodied relief (see Rooke Citation2010b).

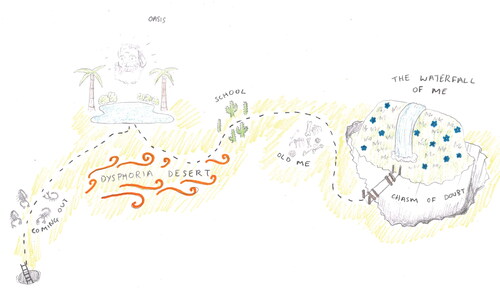

During the first afternoon, participants were creating abstract “maps” of “journeys” they had taken. Sitting alongside Adam, I was surprised that his journey () depicted his anticipated life course (unlike that of others, whose work reflected, for example, hostile others’ gazes and bodily reactions to their presence, difficulty breathing, dysphoria, and dissociative experiences, and relative exhaustions and relief experienced in public spaces). Unraveling the artwork’s “story,” Adam described feeling that as a young trans person he faces a “battle… where you have to go through all these little tests and then you get somewhere.” Expanding, he described his “coming out” as trans and brief space-times of “relief” he crafts amongst everyday exhaustion:

Figure 1 “Journey map” drawn by Adam, showing his past, present, and anticipated future life course. Adam’s favorite author’s name has been digitally removed to maintain his anonymity.

When I first came out to my family, their response was very negative, so the coming out process has actually taken years rather than one conversation. So it was a fight for a long time. It’s a constant process. [Referring to the drawing:] I’m now in this dysphoria desert but there’s an oasis of me finding other people like me. So… I can read [favorite author’s name]’s poetry and feel a connection, feel the relief. I compare [those experiences] to being in a desert and finding water. But [in the background] there’s all these cactuses which are school, it’s a long tiring trek through painful things where I’m constantly being misgendered by people, people forgetting my name, people laughing at me. So after that, there’s this like bridge, and it’s like a broken bridge that I can’t get past right now. And then there’s a chasm of doubt. I imagine myself right there at the moment because I’m still at the stage where I’m like, “is being transgender even real, like is it even a thing or is it like a delusion?” But I know that once I get over that doubt I will get the paradise of being happy with myself and having the life that I wanna have.

Adam and I met later in the year for a one-to-one interview to discuss his life experiences and art practice. As he showed me a creative work portfolio, his experience of a long-held weariness filtered in and out of our conversation. Adam, describing his everyday experience of “loss and time,” added that he “experience[s] transness as a feeling of loss. And basically just a feeling of homesickness… [of having] a phantom body, that you should have that you don’t have” leading to him “feel[ing] like I’m carrying around loss all the time.”Footnote7 Adam voiced anger with this “loss and time” nexus and its connection to his dysphoric experiences when compared to the relative ontological and bodily security that he felt is held by many cis folk:

There’s anger as well.… You walk around feeling like, “Everyone else gets to walk around being fine, why aren’t I fine? Why does that happen?” And I first had that when I was depressed and nobody else seemed to be depressed.… And… the anger I feel towards some cis people… I’m talking about like the man on the street, just a person, who hasn’t done anything wrong. But you can’t help but feel like “how come you don’t even have to think about it?” Like, you wake up in the morning and you’re in a body that makes no sense. And you can’t help but be angry and confused.

Examining Temporalities of Exhaustion Experienced by Adam

Although Adam’s story does not represent every young trans person’s life or bodily experiences, it introduces temporalities of exhaustion that some trans youth might regularly experience. Reflecting on Adam’s story, the constancy and layering of frustrations contribute to his weariness: Once one “fight” is over (including coming out to family), others—being misgendered, grappling with identity and bodily dysphoria—come to the fore. As Amin (Citation2014, 219) notes, examining how “transgender experiences are constituted by [and] yet exceed normative temporalities promises to do justice to the complex ways in which people inhabit gender variance.” Adam continually casts between his past, present, and imagined future selves and experiences, at least partially because of his exhaustion, through flashbacks, intrusive thoughts, “body memories,” and other time-messing mechanisms (Morrigan Citation2017). Adam’s “long tiring trek through painful things,” emergent from external hostile forces, reinforced by his own internal voice, appears to have no mitigating pathway or end point. This reflects how exhaustion can induce a slow time whereby one waits for life conditions to improve, while largely subject to understandings and actions of (potentially hostile or misunderstanding) others, and—in the case of many trans people in the United Kingdom—to societally, socially, and spatially reinforced cisnormative expectations and transphobic hostilities. Adam’s story also emphasizes both the emergence and subsuming of exhaustion through and into the body and its surfaces and interiors (in the ongoing experience of bodily dysphoria and anxiousness). Conversely, Adam’s story reflects the potential and affirmation that can be (re)made from exhaustion, with the safe “oasis” he creates, his accessing of a trans “safe space,” and his immersion in creative practices representing potentially life-saving interruptions to exhaustion’s temporalities.

To explore trans temporalities, I follow trans scholars’ lead to argue that geographers should engage with trans people’s entanglements with(in) time and temporalities, alongside space and spatialities. In particular, I recognize the complex temporal nonlinearity attached to experiencing exhaustion, in contrast to discourses of linearity pervasive around trans lives, which problematically conceptualize trans folk as experiencing both a temporality of “the traumatic past, the intervening present and the hopeful future” (Fisher, Phillips, and Katri Citation2017, 3) and “disjunct time, in which an assignment at birth is retroactively rejected, and a present embodiment is understood as needing to become otherwise in the future” (Chen and cárdenas Citation2019, 475; see also Israeli-Nevo Citation2017). I follow participants’ own articulations of their spatiotemporal experiences, many of which do not adhere to cisnormative understandings of time that might not, for example, recognize the time-messing nature of conditions such as exhaustion, nor temporal reconfigurations that trans youth (re)make through resilient, resistive, and restorative practices. In doing so, I follow simpkins’s (Citation2017) recognition that embodiment and embodied experiences continually emerge through enmeshed “past-present-future becomings” (125), an understanding that recognizes that experiences of temporal nonlinearity are “unique for each body” (126).

Reconceptualizing Exhaustion

Overview: “A Whole Lot More Than Tired”

Exhaustion, for Deleuze ([1992] Citation1995, 3), involves becoming “a whole lot more than tired.” We are said to be living in an “age of exhaustion” induced by capitalist and austere economics, pervasive technology and communications, political mistrust, social marginalization, and anxiety around human sustainability (Ahmed Citation2010; Berlant Citation2011; Neckel, Schaffner, and Wagner Citation2017). More recent work has expanded on societal exhaustion and the weariness experienced by particular communities during COVID-19 (Lupton and Wills Citation2021). Nevertheless, social researchers and theorists have struggled to conceptualize exhaustion geographically. Neckel, Schaffner, and Wagner (Citation2017, 5) argue that exhaustion is characterized by excessive exertion and bodily “fatigue, lethargy, and weakness” and mental “weariness, disillusionment, apathy, hopelessness, and lack of motivation.” For the authors, “being drained… [thus] connects individuals, social classes, growth-oriented capitalism and the ecosystem into a crisis-ridden constellation” (3), suggesting that exhaustion filters horizontally across society. I argue that this supposed “connection,” focus on societal-wide experiences, and discourses presenting exhaustion as complete exertion universalizes experiences and does not consider the varying intensity of exhausting experiences that occur according to bodily and social differences and exclusions. Such approaches cannot fully account for the specificities of the bodies, subject positions, and spatial and embodied interactions of those experiencing exhaustion, nor the specific embodied experiences and processes that exhausted people live through.

Challenging Exhaustion as Initiating an Absence of Possibility or Potentiality

As Wilkinson and Ortega-Alcázar (Citation2019, 157) note, exhaustion and similar conditions have often been “positioned as the antithesis of political action, where individuals are slowly worn down until they no longer have the strength to resist.” Even Deleuze ([1992] Citation1995), in his reading of characters in Samuel Beckett’s work, understands exhaustion as undermining, even removing, one’s ability to “possibilitate.” From this perspective, exhaustion renders it impossible to orient oneself toward possibilities, with exhausted people forced to “press on, but toward nothing” (Deleuze [1992] Citation1995, 4). This conceptualization obscures agency exercised, and resilience crafted by, exhausted people and their bodies to maintain resilience and stability within, or resistance to, exhausting everyday conditions. Indeed, existing work has largely represented exhaustion as “something without value,” potential, and energy, with exhausted or weary bodies understood as “hopeless, stultified, [and] withdrawn” (Wilkinson and Ortega-Alcázar Citation2019, 163). This theorization, in contrast with my young trans participants’ experiences, has often further marginalized those experiencing fatigue. As Gorfinkel (Citation2012, 316) notes, “fatigue is not necessarily antithetical to action, agency—it can… coexist with it, even if… [it] delays action.” In other terms, experiencing or embodying exhaustion does not inherently impede one’s ability to draw on their active agency to enable a livable life or orient toward conditions like gender euphoria, an academically underexamined condition that describes ease and joy felt when experiencing gender affirmation, exploring gender and gender identity, or embodying certain dimensions of one’s gender or transness (Todd Citation2020, Citation2021; Dale Citation2021; Beischel, Gauvin, and van Anders Citation2022).

I build on Wilkinson and Ortega-Alcázar’s (2018) work to consider potentialities enabled through feeling and embodying exhaustion. I both refute Deleuze’s ([1992] Citation1995) presentation of exhaustion as rendering possibilities impossible and align with his recognition that exhaustion initiates the emergence of novel subjectivities. My reading of Deleuze is thus: to have exhausted all possibilities constitutes a fleeting subject position that sits atop a precipice—when pushed so far by the conditions of exhaustion that potentiality cannot seemingly be grasped, a transformative becoming, a drive to propel things forward, emerges. As Ahmed (Citation2013) describes, “shattered,” “diminished,” or “depleted” subjects develop the means “to restore, to replete”; they “find ways of becoming energised in the face of the ongoing reality of what causes their depletion.” Indeed, as trans youth voices demonstrate, this subject-(re)making is far from entirely harmful or vulnerable. Young trans people’s ability to persist, resist, and experience joy in defiance of forces that induce weariness and exhaustion emphasizes their active agency in creating positive, fulfilling life conditions, even while subject to exhausting forces. Indeed, this active agency theorization aligns with geographer Brice’s (Citation2020, 673, italics added) understandings of particular trans embodiments and subjectivities relative to social vulnerabilities, such as that of the radical femme (“a gender-based political aesthetic”; Brice Citation2020, 674), which can emphasize “vulnerability as a radically transformative force of potential… an operative force that can be emphatically and defiantly activated.” Brice expands on the trans specificity of this resistance–vulnerability nexus:

Radical femme and trans experience… remind us that it is precisely by mobilising our vulnerability as subjects—through radical invigoration of diverse practices including, but not limited to, gender expression, care, empathy, solidarity, queer “family,” vigilance, and defiance—that we exceed the constraints of anxious solitude and enact the full transformative potential of our relations with a milieu… [C]oming out, or the taking on of an explicit identity, is not primarily an act of individual self-expression… but rather the expression of an ontological commitment to practising vulnerability. (673)

Developing Geographies of Exhaustion: Spatial Shrinkage and Extended Temporalities

Geographers are particularly well-placed to continue thinking through the co-constitution of particular spaces, temporalities, and exhausted bodies and subjects. As Deleuze ([1992] Citation1995, 10) notes, while implying that living through exhaustion limits, or removes, one’s ability to engage with, and craft potential out of the spaces they encounter, “the consideration of… space gives a new sense and a new object to exhaustion: to exhaust the potentialities of any-space-whatever.” Recent efforts to explore spatialities of exhaustion have arrived as geographers increasingly examine the experiential and emotional politics associated with marginalization and exclusion. Recent publications have considered weariness and endurance in neoliberal, economically austere contexts (Hitchen Citation2016; Wilkinson and Ortega-Alcázar 2018), and embodied emotions emergent through geographies of sexualities (De Craene Citation2017; Gorman‐Murray Citation2017). Geographers have also conceptualized facets of exhaustion relevant to trans youth lives. For example, as Hitchen and Shaw (Citation2019) argues, those most exposed to austere economic affects face a physical shrinkage of their everyday lifeworlds, particularly through a contraction in the number and diversity of spaces available and accessible to them. This spatial shrinkage also occurs when spaces themselves become restrictive, exhausting environments for those enveloped by marginalizing affects and hostile atmospheres that emerge and are felt (perhaps only) by specific individuals and communities. As Deleuze ([1992] Citation1995, 10) articulates, “[s]pace enjoys possibilities as long as it makes the realisation of events possible.”

Meanwhile, Wilkinson and Ortega-Alcázar (Citation2019, 158) have complicated weariness, emphasizing its “messy paradoxical [nature as] a scene of exhaustion and endurance, diminishment and fortitude, decay and aliveness.” This understanding demonstrates that exhausted people and bodies can experience everyday spaces and times through seemingly paradoxical states: both depletion and renewal, impossibility and potential. This paradox is reflected in trans youth lives: Burnout, resilience, resistance, joy, despair, worry, gender euphoria, anxiety, and exhaustion are often bound up and lived through simultaneously or in close spatiotemporal proximity. I am also inspired by Wilkinson and Ortega-Alcázar’s (Citation2019, 156) turn to the “slow and steady deterioration” and “slow violence and everyday endurance” that welfare cuts bring about in those who they most affect. As Hitchen (Citation2021) articulates, austerity therefore initiates a lived temporality that is not bound to a particular moment or “cut,” but is an ongoing condition with an obscured end point or resolution. This approach recognizes temporalities of exhaustion, including “durational everyday forms of slow suffering, those moments where violence is experienced as continuation rather than an eruption” (Wilkinson and Ortega-Alcázar Citation2019, 156, italics added).

These understandings of exhaustion’s extended temporalities highlight how exhaustion emerges and takes root in marginalized people’s bodies and subjectivities when they experience dislocating, temporally disjointing, and exhausting affects with commonplace frequency and constancy. The intensity of exhaustion is exacerbated iteratively, therefore, by the frequency with which one experiences exhaustion-inducing affects and encounters. As Ahmed (Citation2014) tells us, suggesting that weariness and exhaustion occupy a rhythmic, cyclical pattern that builds force as its events accumulate, “We can be exhausted by what we come up against. And then we come up against it again.” This gradual accrual of exhausting affects resonates with trans lives, with Ahmed (Citation2016, 27) comparing societal discourses leveled against trans people to a “volume switch… already stuck on full blast.”

Existing Queer Exhaustion Conceptualizations

A small literature in psychology and mental health studies has examined queer people’s experiences of exhaustion, typically framed as burnout or “minority stress” linked to microaggressions and overt violences (Cyrus Citation2017). This literature has focused on cisgender lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) people’s experiences (e.g., Toomey et al. Citation2018), whereas others have examined the intense “minority stress” experienced by LGB people of color (Cyrus Citation2017) and queer activists of color (Vaccaro and Mena Citation2011). Meanwhile, Nicolazzo (Citation2017) has explored the “burden” of “practicing [or] educating others about trans* genders” on U.S. college campuses, explaining how their participants were “overwhelmed” or “feeling tired, worn out, or exhausted” from undertaking a continual practicing–educating cycle.

Studies of trans-specific experiences of “minority stress” or exhaustion have been more limited (although see Nicolazzo Citation2017). Rood et al. (Citation2016, 152), however, explore the anticipatory nature of trans people’s experiences of “minority stress” through their everyday “expectations regarding the likelihood of stigma being enacted” upon them because of their transness. Meanwhile, nonacademic queer folk have described “queer burnout” to, for example, demonstrate how hostilities emerge “in endless waves” from multiple sources, such that trans folk devote significant “thinkspace to qualifying their existence to a society that simply wishes they would cease to” (Fairchild Citation2019). Yet queer fatigue also originates through masking or suppressing queerness and transness. For example, recent media attention has focused on the “code-switching” practices of LGBT+folk and people of color (POC), highlighting exhausting efforts required to “tone down” or “blend in” to particular spaces and social settings to avoid causing discomfort to themselves or minimizing conflict with less marginalized bodies (see British Broadcasting Corporation Citation2018; Holden Citation2019).

Queering Exhaustion Through Sara Ahmed

My own queer approach to exhaustion is influenced by Sara Ahmed’s work, which reinforces that fatigue and weariness are shaped by repetitive actions and events involving marginalization and exclusion. For example, Ahmed (Citation2004) emphasises that events and actions that seek to position queer folk as “other” or “failed” relative to assumed and dominant heterosexuality or cisnormativity (and expectations of binary cisgenderness), can constitute violence that subsumes into queer bodies. As Ahmed (Citation2013) describes, engaging Audre Lorde, such oppressions “can be experienced as weather… press[ing] and pound[ing] against the surface of a body”; oppressed subjects and bodies survive the exhaustion this pressuring creates by “hardening” to withstand marginalizing or hostile sociomaterial conditions. This weather metaphor emphasizes the varying intensities through which exhaustion can emerge and be felt and the complex, sudden, or gradual and durative ways that exhausting affects can arrive and exert force. Indeed, Ahmed’s language of injury, bruising, and bodily subsuming reinforces the extended temporalities and emotionally and bodily scarring effects of queer marginalization, exclusion, and “out-of-placeness” through structural and institutional affects.

To relate these ideas to young trans lives specifically, I draw on Ahmed’s anticipatory exhaustion to understand how being “out-of-place” within space-times of the present might spark feelings of dread and exhaustion toward future events and encounters that might become imbued with emotions such as fear and anxiety before they take place. Trans youth might thus feel already exhausted by the force of such events’ and/or spaces’ potential (or imagined) affective and sociomaterial composition. For example, Ahmed (Citation2017) explains how those embodying a “feminist killjoy” position, given their heightened awareness of misogynistic structures that impede women and their bodies, develop anticipatory exhaustion relative to(ward) future events:

Sometimes… we experience an anticipatory exhaustion: we line ourselves up to avoid the consequences of being out of line because we have been there before and we can’t face it anymore.… Other times we might realize: we are willing to pay the costs of not being in line because getting in line would compromise too much. (55, italics added)

As my research revealed, some trans youth often choose to conform to cisnormative expectations or otherwise avoid conflict that arises through others’ understandings of their transness (although this sinking into space can also constitute a radical falling out of line). As Ahmed (Citation2017) explains, trans people might have to repeatedly “insist” to be heard, to have their preferences respected (see, e.g., Nicolazzo Citation2017): To avoid this insistence, and inhabit a “desire for a more normal life… can be a desire to avoid the exhaustion of having to insist just to exist” (Ahmed, Citation2017, 122, italics added). In other terms, exhaustion can emerge as a consequence of living authentically and openly. As many participants demonstrated, the value of embodying this authenticity (by, e.g., “coming out,” presenting an authentic self through hair and clothing, transgressing societally enforced gender norms, and other means of escaping “gender tyranny”; Doan Citation2010) can become more important than its potential consequences for their mental and physical well-being or long-term stability and survival, whether or not they seek to be defined by their transness.

For many trans youth, to be exhausted, then, can involve being presented with opportunities to fall “out of line” and to create new lines and alignments for resilient, resistive, and restorative ways of being. Trans youth surviving in their visibility or even continued existence in cisnormatively regulated everyday spaces, resilient in their formation of networks and communities out of hardship and hostility, and persistent in their maintenance and (re)making of trans spaces and everyday spaces alike, illustrate this expansive queer potentiality.

In the following sections, I bring exhaustion’s temporalities in conversation with trans youth narratives. The first section discusses the constancy or onslaught of trans hostility and agency-limiting encounters as a temporality many participants described experiencing.

Young Trans People’s Stories of Exhaustion and Its Temporalities

Constancy and Onslaught

The last year… it’s just been relentless, it’s just been absolutely awful.… Every now and then I’ve realized that what’s coming out of the GRA [Gender Recognition Act] consultations, it kind of would seep into how I would perceive myself and erm, like, I don’t know… it was just really, yeah, it was just really awful.… But yeah [struggling to speak]… like in the last year, I have gone through periods of being just so down, because when people are just hating you so much for just being, it’s quite hard. And I’ve suddenly become very anxious about [dating]. And I think I’ve realized, I think it’s because I’ve read so many of these like, these people on Twitter kind of saying like, you know, “Who would date that,” you know, that sort of thing.… [deep inhale] because a lot of the time when you read what other people say, they don’t just say like, “Oh, I feel like this about a certain issue,” they’re like, “All people feel like this.”… Erm, it is tough. (Wes, he/him, 22–25)

Almost all participants conveyed weariness emergent from the constancy of, for example, negative experiences they were facing; anxious, dysphoric, or fearful internal dialogues they frequently negotiated; and the regularity of encounters that seemed designed to limit, or even remove, agency and autonomy. For example, participants regularly described encountering persistent misgendering and arbitrary gatekeeping across myriad spaces, experiencing “stifling environments” (Michael, he/him, 14–17) across everyday sites including home and educational spaces, and continually negotiating social and bodily dysphoria. Meanwhile, many participants described feeling like their “existence is making other people uncomfortable” (Rhys, he/him and they/them, 14–17) and talked of being constantly preoccupied with anticipating others’ potentially hostile gazes.

Facing the incomprehensibility, pervasiveness, and onslaught of so many ongoing external and internal hostile and spatially and bodily dislocating forces (many unique to the UK context), as demonstrated by Wes earlier, led many participants to convey anxiousness about potential future events and describe constantly feeling worn down and sometimes unable to generate “ways out” of the exhaustion this wearing away created. Wes’s narrative reflects how the temporal constancy and relentlessness of trans-hostile affects, practices, and forces “seep into” or slowly creep into aspects of young trans people’s subjectivities, including their bodily comfort, mental well-being, self-perception, and ability to self-affirm, reflecting the slow violence that the constancy of transphobic hostility can exact.

Exhaustion felt through facing and receiving a constancy of affects that wear away, or contribute to the experience of spaces along lines of embodied anxiety and intense tiredness, was reflected by many participants. Osh’s (they/them, 18–21) life story exemplifies this and the everydayness of exhaustion (and indeed their artwork they brought to a one-to-one research encounter displayed a self-image alongside the words “I’m Exhausted… of Being Exhausted…”). After describing how they have “held back from coming out at work” to avoid “hav[ing] to explain [trans] and become an educator there and [then] have some people disagree with it and some people make my life more difficult when I’m there,” we held the following conversation:

James [Researcher]: What are you imagining in your head when you think about this kind of stuff?

Osh: I don’t even know because if you look at the amount of shit that’s been going on with like everything at the moment, fucking like everything, so much shit has gone downhill. Even in London, it’s not just the U.S., it’s everywhere now.

James: Especially because of the GRA stuff giving them [transphobic/hostile people] a voice.

Osh: It’s given them a voice. And like stuff on the tube. My friend like saw posters up and it was just… you know, that’s really scary. I already have intrusive thoughts and I have a lot of problems with catastrophizing everything so my brain goes, “If they don’t like you they could stab you for all you know, like you don’t know what’s going to happen.” So like, um, I’ve held back anything like that. I’ve held back like even like smaller parts of my personality, just like the things I’m interested in, I hold back on. And the things, like how enthusiastic I am about things, I’ve done that most of my life.

James: Does that holding back have an element of exhaustion?

Osh: Oh hugely. I’m perpetually tired. I’m perpetually like so, so, so tired just in general because I’m constantly monitoring what I’m saying and how much, like how I’m coming off.

I also asked Osh about their exhaustion’s spatial origins. Their response typifies how, for many trans youth, exhaustion forms a continuous presence with few clear spatial or temporal boundaries:

Osh: It’s more like a constant presence… but there’s a variation depending on who I’m with and in what social context I’m in, cos OK, like at work there’s a need to be professional… whereas like I’m at home or with my girlfriend I’m pretty much just like lowest gauge and I’ll talk about whatever I want, like it’s fine. But if I’m at home with my parents, I’ll only mention that maybe a little bit, and I won’t go into detail on it.… I’m always monitoring how I come off…

James [Researcher]: And that self-monitoring, does that extend to the way that you portray yourself or hold yourself in life situations… [and the] way that you like hold your body like in spaces…

Osh: Oh, yeah, if it’s a space where I feel like I am under threat or I’m like, or if it’s a space in which I feel like I’m criticized which is hard for me but I’ll like cave inwards on myself, I won’t make eye contact with them as much as possible, I’ll look at the floor, I’ll look away, I’ll look up, I’ll keep everything sort of down and submissive

James: Is that sort of like burying the transness as well?

Osh: Hugely.

Certain young people experienced the constancy of exhaustion-inducing affects and encounters with a particular intensity as they simultaneously faced a constancy of multiple oppressions along intersectional lines of “race” and racialization, disability, age, sexuality, and so on. Certain participants were aware of relative embodied privileges they held relative to other young trans people who might experience “out-of-placeness” and exhaustion with particular frequency/force. As Tom (he/him, 18–21), a young trans man of color told me:

I walked into [supermarket chain store] just across [from home] and the first thing I saw was the front page of [a newspaper] saying “Transgender sex beast, xyz…,” like whatever… this is directly across from my accommodation and thank goodness I’m not 100 percent a visible trans person, but I know there are other people in my accommodation who are. Like, and I know that [they have been attacked there]. I know of [incidents] of trans female friends, always, being attacked or kicked or just you know had nasty words said to them. So it’s like here’s the problem, first of all, it’s right across the road being sold in the supermarket for a penny. So it absolutely does filter into my life and it’s greatly upsetting. [However] I do have the privilege of being able to compartmentalize it because realistically I don’t face a huge amount of discrimination specifically for being trans, cos I have that privilege of being able to just fly under the radar and be pretty much as invisible as I was before [but] it affects my friends, and that affects me, and it could very well affect me on a really bad day. It’s… completely heartbreaking, really… I mean, what else can I say about it? It won’t even have just been in that one [supermarket chain] will it? It will have gone out to all of them. Anywhere I could be walking, somebody could be walking with that newspaper, I could be walking with a trans friend who is a lot more visible than me…

In a further example, Cal (he/him, 14–17), a young trans POC described experiencing misgendering from cisgender POC (both queer and straight), marginalization within queer POC communities, and difficult home and school life experiences wherein he, his body, and his self-expression were restricted and controlled. Such experiences contrast his gender and selfhood being regularly affirmed and celebrated in “safe spaces” for trans youth. His story demonstrates how affects and social encounters inducing exhaustion can, for many trans youth, infiltrate everyday life spaces:

Cal described feeling like he “can’t get it right” in certain, if not all, settings, and felt he faced scrutiny in all spaces. Cal explained feeling that he often feels like he is “seen only as trans,” because of his visible transness, adding that he feels that he experiences street harassment as others see him as “a rarity” because he is queer, trans, and a POC. He talked of “verbal violation” he has subsequently experienced his almost constant feeling of being “on edge.” Cal also spoke about his school experiences, describing them as “painful.” He told us that “being trans at school is a full time job,” talking of the excessive scrutiny he experiences there, and the school’s lack of knowledge or support around trans-specific issues he faces. After telling me about his health difficulties, bruising he was experiencing while binding, and his experience of dysphoria, he told me more about his difficult family relationships. For him, GI had provided something to fall back on, becoming a place to retrieve guidance in the absence of familial support. A residential countryside visit for young queer POC, involving story-sharing, muddy walks, and crafts, allowed Cal to feel “five days of being mentally well, and feeling positive and relaxed”; indeed, for him, the trip created spaces that felt even more safe than GI. However, “coming down” from being embroiled in such a utopic place caused anxiety to set in. Ultimately, he described the residential as a “glamourized version of life.” (Field note excerpts, 11 December 2018Footnote8)

Cal’s experiences resonate with other participants’ stories, although most noted the positive, life-saving consequences of being embroiled in exclusively trans/“safe” spaces as, for example, “somewhere where you can just breathe, even if it’s just for a few hours” (Kane, he/him, 18–21), including those of GI and more informal or ephemeral activist spaces, both of which become sites of resilience, resistance, and restoration (i.e., from exhaustion and “out-of-placeness”). Crucially, atmospheres, practices, and affects of such “safe” sites lodge as embodied memories, forming a bodily archive of potentials that make possible the generation of altered, more positive, or affirming, future encounters.Footnote9

Waiting and Temporal Unboundedness

I tend to see… waiting as the only thing keeping me from being my ultimate self. (Jón)

… Acknowledging that my situation is temporary is helpful cos I’m like “in six months’ time my situation will be different, I’ll be getting my study leave, I’ll do my A-Levels and then I won’t be in this situation.” And so like that anticipation and waiting sucks but it’s like I’m waiting for something and that’s OK.… Like next year I’m like saving up money so I can go to an adult gender clinic, my parents won’t pay for me to go, [sarcastically:] lovely people [sighs deeply]. When I’m 18, I’ll get the other opportunities which will make me feel better which I don’t have now, and I’m just counting down the days when I’m not at school, or I don’t have to live at home any more… (Cal)

As Jón and Cal’s words attest, participants often described waiting as a particularly exhausting experience that suffuses their everyday lives. Unlike in stories featured thus far, Cal is “waiting for something”—situations, spaces, and times that will allow him to live more authentically, rendering the situational and temporary nature of his exhaustion particularly clear. In this sense, his exhaustion is about anticipation and enduring present conditions. He immerses himself in trans and queer collectives and spaces, changing into clothes he feels more comfortable in wherever possible, and so on, to reach times of greater autonomy. Cal’s words radically reaffirm the flourishing of young trans people’s agency within times of exhaustion and in spite of structures and actions that (attempt to) impede it.

Speaking more generally, Eilidh (she/her, 22–25), reading from a participatory diagram that summarized a group of participants’ thoughts on “waiting,” described:

So what have we got?… There’s “things we wait for,” “waiting to be old,” “blood results,” yeah that’s a big one, “waiting for others to get their shit together” [everyone laughs], err, [waiting for] “the Tavi” [collective groan], “the GRA consultation” [everyone laughs], “doctor appointments slash referrals,” errm “blood tests or results” again, and “family support.”Footnote10

Thinking of sort of the medical route again, when you go to a referral you do that one moment and then you’re sort of expected to just… wait until you get the next bit of information, could be maybe six weeks before your appointment, it could be at any stage. Um… so I was thinking about like sort of layers of waiting that we have as well. And in waiting for an appointment, you’re also waiting for the system to change, you’re also waiting for the government to change how they approach the whole situation, you’re also waiting for [many other things]…

Eilidh’s words also demonstrate that waiting often emerges from and around unknown or imperceptible sources, with the vagueness of “waiting for the system to change” exemplifying how waiting for trans youth often simply constitutes a constant embodied condition. For many trans youth without easy access to such spaces or mechanisms as healthcare (or even those with such access), it feels unlikely that this constancy will recede within a recognizable timeframe. Even when the source of waiting is clear or locatable (e.g., at the scale of “the government”): These sources and mechanisms tend to be those that trans youth exert limited or no control over, are subject to sociopolitical volatility, or are reliant on public and governmental goodwill and trans-inclusive allyship/agencies. This obscurity and emotional intensity while waiting can be exacerbated by certain social processes, as Jón (he/they/“something else,” 18–21) explained:

Waiting is such a lonely process, especially when it’s one that’s completely devoid of communication, then you end up very, very alone. So to be able to turn to other people [using a trans-led social media chat function] in similar boats and be like, “Aahhhh my doctor hasn’t communicated to me,” or whatever, and other people can go, “Ughh same,” then suddenly it’s still shit, but it’s not a lonely process. There are other people going through similar things, and you can talk about them.

Extreme frustration and weariness emergent from limited control over everyday life conditions was captured by many other participants. For instance, Mark (he/him, 18–21), whose weariness with facing with the violence of deliberate and persistent misgendering, and the ongoing role this played in his life, structured much of our story-sharing. After sharing stories of his experiences of being read as a woman, and being misgendered in everyday spaces such as banks and nightclubs where notions of binary gender often dominate with greater intensity (albeit for both similar reasons such as bodily surveillance and showing forms of official identification and for differing reasons and as a result of differing affective forces, such as having difficulties amending documentation and cisheteronormative expectations in certain nightclub spacesFootnote11), Mark told me:

I was put in an inpatient unit a few months ago, and in there I had just endless misgendering. Like my care plan just said “she” all the way through and I was like ughhhh. I was like, “I’m already in a state and now you’ve handed me this care form which misgenders me throughout it.” [becoming angrier]: I don’t have the ENERGY to fight that battle. I had to have a massive argument with the ward manager, and it’s like, “I’M REALLY NOT WELL,” I shouldn’t be having those kind of arguments.

I ended up on a female ward because I didn’t have any fight left in me, and I was like, “I can’t actually fight this battle,” but the second you say that, you let them, you end up in shit situations. I think it’s that kind of finding someone else in the same situation as me, for me it was finding Paul and both of us going, “This isn’t OK, we’re going to get through this and stand up to this.” And that gave us both kind of the willpower and energy to fight it, to be like it’s not OK.

Conclusions: Spaces, Times, Bodies, and Trans Youth in the Context of Exhaustion

This article has explored young trans people’s everyday stories of exhaustion in the UK and has considered how their exhaustion surfaces and becomes embodied during the onslaught of myriad, often trans-hostile or agency-limiting forces acting against trans youth, many of which are unique to or particularly acute within the current UK context. Throughout, by paying theoretical attention to the embodied experience of exhaustion, I have argued for a reconceptualization of exhaustion that emphasizes the specificities of the bodies, bodily experiences, subject positions, and spatial interactions of those who encounter and live through the condition. By illuminating exhaustion’s nonlinear, messy, and often prolonged temporalities, I have observed that such temporalities constitute a function of lived exhaustion while paradoxically making possible its potentialities. Indeed, by queering exhaustion following Sara Ahmed, I have made the case that to receive the violence and onslaught of exhaustion-inducing forces is to be given opportunities to embody the potential to create new lines and alignments for living through hostile everyday life conditions authentically and purposefully. Young trans people’s stories attest to the hopeful, resilient, and persistent capacities of young trans people, trans communities, and trans and queer spaces to survive and flourish within exhausting life conditions. This article has demonstrated that certain trans youth often experience and orient toward a queer futurity that, if not utopic and entirely rejecting of the “here and now” (Muñoz Citation2009), is enough in that young people can live with the here and now and craft stability and (self-)affirmation from present everyday conditions. Crucially, I have contended that trans youth who continually experience and embody exhausting life conditions can, paradoxically, (re)claim agency, (re)make space, and produce new, affirming connections to(ward) spaces, bodies, communities, and future events and encounters that counter “out-of-placeness” and induce such experiences as gender euphoria.

By emphasizing the possibilities and potentialities created through embodying an exhausted body and subject position, I have highlighted the importance of radical (if paradoxical) restorative and resilient practices, and “safe” and trans-affirming spaces (whether formally organized or created by young trans people themselves) for the development and maintenance of embodied comfort, authenticity, active agency, and queer and trans potentiality while enduring exhaustion’s temporalities. I argue that temporalities of exhaustion, far from initiating a falling-away of self-affirmation, can hold the potential (for particular trans youth in certain contexts) to induce radical flourishing and (re)making of trans youth subjectivities and bodies. In other words, I have demonstrated that young trans lives are composed of much more than mere endurance of the present. In light of this, I contend that we cannot unbind exhaustion, like “out-of-placeness,” from resilience, resistance, and restoration, and it is both the spatial and temporal conditions lived with, and affirmative practices and spaces generated by, marginalized individuals and communities that should capture our attention when turning to exhaustion.

Acknowledgments

Deep and truly heartfelt thanks go to the young trans people who contributed to and collaborated in this research, and to Gendered Intelligence for both their life-enriching work and for supporting the research. I am also grateful to Rachel Colls and Elizabeth Johnson for their readings of an earlier version of this article and to the three anonymous peer reviewers who provided insightful comments.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

James David Todd

JAMES DAVID TODD is a Fixed-Term Lecturer in Human Geography in the School of Geographical and Earth Sciences, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, Scotland, G12 8QQ, UK. E-mail: [email protected]. James’s research focuses on trans and queer lives, spaces and bodies and other queer geographies. James is particularly interested in everyday life, participatory research, and feminist geographies of embodiment, affect, and temporality.

Notes

1 To maintain anonymity and to account for the potential fluidity of participants’ gender(s), I refer to participants using an age range (14–17, 18–21, or 22–25) and the pronouns they used in each research encounter.

2 I use “queering” and “transing” to refer to practices that (re)make spaces in a particularly trans or queer-oriented direction (Crawford Citation2015).

3 As the largest UK LGBT + survey conducted to date, it reached 108,100 LGBT + people aged sixteen and over living in the United Kingdom; 3 percent were trans men, 3 percent were trans women, 7 percent were non-binary and 2 percent were intersex.

4 Like much geographical research (March Citation2021), this geographies of sexualities work (rather than more recent literature—much of which is cited within this article—that I situate within an emergent “trans geographies” canon) has tended to problematically universalize trans people’s lived experiences and marginalize trans lives (Todd Citation2021). I situate my work within and alongside this more recent “trans geographies” literature.

5 Note that most participants were young trans men and non-binary people. Although several participants were trans women, given the constraints of the research and its organizational embeddedness, trans women were underrepresented.

6 I am queer and gay and identified as cisgender at the time of the research.

7 Note that most participants did not describe their lives and bodies in these terms.

8 As one participant did not wish to be recorded, I wrote detailed field notes based on extensive participatory diagrams constructed with workshop participants, incorporating their phrasing after this session.

9 Crawford (Citation2010, Citation2015) also described emotional expectations or responses to spaces as permeating into specific sites’ materialities, such that physical architectures become “virtual archives of affect” (Crawford Citation2010, 519).

10 “Tavi” refers to the Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust, one of two Gender Identity Development Service (GIDS) clinics in England.

11 These examples also indicate how pervasive misgendering and cisnormativity can be, and that anxieties felt by many trans youth around bureaucracies of gender policing, mediated through the state (e.g., needing to show ID at a bank or nightclub) can surface continually

References

- Abelson, M. J. 2016. “You aren’t from around here”: Race, masculinity and rural transgender men. Gender, Place and Culture 23 (11):1535–46. doi: 10.1080/0966369X.2016.1219324.

- Ahmed, S. 2004. The cultural politics of emotion. Edinburgh, UK: Edinburgh University Press.

- Ahmed, S. 2010. The promise of happiness. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Ahmed, S. 2013. Feeling depleted?. feministkilljoys. Accessed January 24, 2020. https://feministkilljoys.com/2013/11/17/feeling-depleted/.

- Ahmed, S. 2014. Feminist hurt/feminism hurts. feministkilljoys. Accessed October 30, 2019. https://feministkilljoys.com/2014/07/21/feminist-hurtfeminism-hurts/.

- Ahmed, S. 2016. An affinity of hammers. TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly 3 (1–2):22–34. doi: 10.1215/23289252-3334151.

- Ahmed, S. 2017. Living a feminist life. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Ahmed, S. 2019. The same door. feministkilljoys. Accessed December 5, 2019. https://feministkilljoys.com/2019/10/31/the-same-door/.

- Amin, K. 2014. Temporality. TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly 1 (1–2):219–22. doi: 10.1215/23289252-2400073.

- Anderson, B., and J. Ash. 2015. Atmospheric methods. In Non-representational methodologies: Re-envisioning research, ed. P. Vannini, 34–51. London and New York: Routledge.

- Anderson, G. 2019. Non-conforming gender geographies: A longitudinal account of gender queerness in Scotland. PhD diss., School of Geographical and Earth Sciences, University of Glasgow.

- Andrucki, M., and D. J. Kaplan. 2018. Trans objects: Materializing queer time in US transmasculine homes. Gender, Place and Culture 25 (6):781–98. doi: 10.1080/0966369X.2018.1457014.

- Arun-Pina, C. 2021. Micro-liminal spaces of (mis)gendering: The critical potential of trans-pedagogy in post-secondary institutions. ACME: An International E-Journal for Critical Geographies 20 (5):509–30.

- Beischel, W. J., S. E. Gauvin, and S. M. van Anders. 2022. “A shiny little gender breakthrough”: Community understandings of gender euphoria. International Journal of Transgender Health 23 (3):274–94.

- Bender-Baird, K. 2016. Peeing under surveillance: Bathrooms, gender policing, and hate violence. Gender, Place and Culture 23 (7):983–88. doi: 10.1080/0966369X.2015.1073699.

- Berlant, L. 2011. Cruel optimism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Bissell, D. 2016. Micropolitics of mobility: Public transport commuting and everyday encounters with forces of enablement and constraint. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 106 (2):394–403.

- Brice, S. 2020. Geographies of vulnerability: Mapping transindividual geometries of identity and resistance. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 45 (3):664–77. doi: 10.1111/tran.12358.

- Brice, S. 2021. Trans subjectifications: Drawing an (im)personal politics of gender, fashion, and style. GeoHumanities 7 (1):301–27. doi: 10.1080/2373566X.2020.1852881.

- British Broadcasting Corporation. 2018. Code-switching: How BAME and LGBT people “blend in.” Accessed October 30, 2019. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/newsbeat-45978770.

- Browne, K., C. J. Nash, and S. Hines. 2010. Introduction: Towards trans geographies. Gender, Place and Culture 17 (5):573–77. doi: 10.1080/0966369X.2010.503104.

- Campkin, B., and L. Marshall. 2017. LGBTQ + cultural infrastructure in London: Night venues, 2006–present. London: UCL Urban Laboratory.

- Cavanagh, S. L. 2018. Toilet training: The gender and sexual body politics of the bathroom. In Queering the interior, ed. A. Gorman-Murray and R. Cox, 172–84. London: Bloomsbury.

- Chen, J. N., and m. cárdenas. 2019. Times to come: Materializing trans times. TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly 6 (4):472–80. doi: 10.1215/23289252-7771639.

- Costello, L., and D. Duncan. 2006. The “evidence” of sex, the “truth” of gender: Shaping children’s bodies. Children’s Geographies 4 (2):157–72. doi: 10.1080/14733280600806940.

- Crawford, L. 2010. Breaking ground on a theory of transgender architecture. Seattle Journal for Social Justice 8 (2):515–39.

- Crawford, L. 2015. Transgender architectonics: The shape of change in modernist space. Farnham, UK: Ashgate.

- Cyrus, K. 2017. Multiple minorities as multiply marginalized: Applying the minority stress theory to LGBTQ people of color. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health 21 (3):194–202. doi: 10.1080/19359705.2017.1320739.

- Dale, L. K., ed. 2021. Gender euphoria: Stories of joy from trans, non-binary and intersex writers. London: Unbound.

- DasGupta, D. 2018. Rescripting trauma: Transgender detention politics and desire in the United States. Women’s Studies in Communication 41 (4):324–28. doi: 10.1080/07491409.2018.1544011.

- DasGupta, D. 2019. The politics of transgender asylum and detention. Human Geography 12 (3):1–16. doi: 10.1177/194277861901200304.

- DasGupta, D., R. Rosenberg, J. P. Catungal, and J. J. Gieseking. 2021. Pedagogies of queer and trans repair. ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies 20 (5):491–508.

- De Craene, V. 2017. Geographies of sexualities: Bodies, spatial encounters and emotions. Tijdschrift Voor Economische en Sociale Geografie 108 (3):261–74. doi: 10.1111/tesg.12256.

- Deleuze, G. 1995. The exhausted, trans. A. Uhlmann. SubStance 24 (3):3–28. doi: 10.2307/3685005.

- Di Pietro, P. J. J. 2016. Decolonizing travesti space in Buenos Aires: Race, sexuality, and sideways relationality. Gender, Place and Culture 23 (5):677–93. doi: 10.1080/0966369X.2015.1058756.

- Doan, P. 2010. The tyranny of gendered spaces—Reflections from beyond the gender dichotomy. Gender, Place and Culture 17 (5):635–54. doi: 10.1080/0966369X.2010.503121.

- Fairchild, P. 2019. Battle fatigue and the transgender community. Medium. Accessed October 18, 2019. https://medium.com/@Phaylen/battle-fatigue-and-the-transgender-community9834e5896676.

- Fernández Romero, F. 2021. “We can conceive another history”: Trans activism around abortion rights in Argentina. International Journal of Transgender Health 22 (1–2):126–40. doi: 10.1080/26895269.2020.1838391.

- Fisher, S. D. E., R. Phillips, and I. H. Katri. 2017. Trans temporalities. Somatechnics 7 (1):1–15. doi: 10.3366/soma.2017.0202.

- Furman, E., A. K. Singh, C. Wilson, F. D’Alessandro, and Z. Miller. 2019. “A space where people get it”: A methodological reflection of arts-informed community-based participatory research with nonbinary youth. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 18:160940691985853–12. doi: 10.1177/1609406919858530.

- Gleeson, J. J., and J. N. Hoad. 2019. Gender identity communism: A gay utopian examination of trans healthcare in Britain. Salvage 7:177–95.

- Goh, K. 2018. Safe cities and queer spaces: The urban politics of radical LGBT activism. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 108 (2):463–77. doi: 10.1080/24694452.2017.1392286.

- Gorfinkel, E. 2012. Weariness, waiting: Enduration and art cinema’s tired bodies. Discourse 34 (2–3):311–47.

- Gorman‐Murray, A. 2017. Embodied emotions in the geographies of sexualities. Tijdschrift Voor Economische en Sociale Geografie 108 (3):356–60.

- Gorman-Murray, A., S. McKinnon, D. Dominey-Howes, C. J. Nash, and R. Bolton. 2018. Listening and learning: Giving voice to trans experiences of disasters. Gender, Place and Culture 25 (2):166–87. doi: 10.1080/0966369X.2017.1334632.

- Hitchen, E. 2016. Living and feeling the austere. New Formations 87 (87):102–18. doi: 10.3898/NEWF.87.6.2016.

- Hitchen, E. 2021. The affective life of austerity: Uncanny atmospheres and paranoid temporalities. Social & Cultural Geography 22 (3):295–318. doi: 10.1080/14649365.2019.1574884.

- Hitchen, E., and I. Shaw. 2019. Intervention: Shrinking worlds: Austerity and depression. Antipode Foundation, March 7, 2019.

- Holden, M. 2019. The exhausting work of LGBT code-switching. Vice. Accessed October 16, 2019. https://web.archive.org/web/20191016170740/https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/evj47w/theexhausting-work-of-lgbtq-code-switching.