Abstract

This article seeks to highlight the need for the development of enhanced and adaptive strategic decision-making frameworks for mega infrastructure investment. The authors contend that contagious narratives about ‘the global infrastructure-gap’, and related estimates of more geographically-specific ‘infrastructure deficits’ are in danger of effectuating inapt outcomes if set against the multiple critical challenges of the 21st century and failing efforts at meeting global and local goals of sustainable development. They argue that as new knowledge and evidence emerges about the advances made and damage incurred by past mega infrastructure investments, and as prospects offered by new technological horizons evolve, it is timely to systematically scrutinise previous practice to ascertain what has been done well and what has not, and decide what should be done differently to deliver more sustainable outcomes. It is argued that research and development of this kind can significantly benefit from new scientific findings and technological innovations fast being brought into the public domain, informing more resilient investment approaches when accompanied by meaningful analyses of the sensitivities of key contextual forces that mould infrastructure development.

1. Introduction

1.1. Preamble

It has been claimed that infrastructure experts and the eloquence of their arguments when promoting megaproject investments, and mega transport projects (MTPs) in particular, have been misleading in terms of the outcomes and impacts promised as compared to those that are ultimately generated and delivered (Flyvbjerg, Bruzelius, and Rothengatter Citation2003; Dimitriou, Ward, and Wright Citation2013). On occasion, this ‘agent of change’ rhetoric is alleged to be duplicitous (Locatelli et al. Citation2017), although at other times it is simply perceived to be the result of too narrow a framing of such projects by these experts and the politicians/stakeholders they serve (Allport Citation2011; OMEGA Centre Citation2012). In some instances, project outcomes have surpassed expectations, whilst in others they have had unintended and unexpected consequences (Hall Citation1980). The article discusses these differing perspectives with a view to offering some insight and clarity as to the reasons for such mixed messages. It is not presented as a scientific discourse in the conventional academic sense but is more of a ‘critical commentary’, an essay that flags some of the important issues and contested areas of debate, and asks how these might be addressed to make megaproject investments more effective and sustainable in efforts seeking to deal with infrastructure deficits.

To facilitate the discussion, the article starts with a brief explanation of the different ways in which infrastructure is often categorised in very basic terms, differentiating between what some parties refer to as ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ infrastructure, and others as ‘economic’ and ‘social’ infrastructure (World Bank Citation2010 and OECD Citation2017, respectively). This is done to not only help address any outstanding definitional ambiguities, but also to aid understanding of how the concept of ‘the global infrastructure gap’ has emerged and the broad assumptions employed in estimating both the global infrastructure deficit and infrastructure deficits at other sub-global scales. Thereafter, we explain the reasons for focusing on mega infrastructure projects, why generally such projects are built and for whom, and who typically finances and funds them, and why.

The article then draws on what we consider to be five important international publications and the lessons they offer infrastructure development, which have influenced our understanding of megaprojects as agents of change. Drawing additionally from the research findings derived from the OMEGA CentreFootnote1 and our extensive international experience in professional practice in infrastructure development in both the public and private sectors in the developed and developing worlds, we seek here to provide our thoughts and insights, albeit somewhat selective, into how infrastructure investment studies could be better framed given the state of flux in an increasingly uncertain world. This is done with a view to encouraging such investments to more effectively address 21st century development visions and aspirations, illustrating how they might contribute to or detract from sustainable development goals, and suggesting how the success of such interventions be judged fit-for-purpose. The implications and ramifications of these thoughts and ideas are subsequently discussed in the light of an often unpredictable and sometimes volatile environment in which the perceived benefits of globalisation are being increasingly challenged.

The proposals and conclusions offered by the article are presented not so much as a ‘silver bullet’ response to the numerous 21st century development challenges, but rather to help explain why and how infrastructure specialists and other stakeholders need to urgently re-frame the planning, appraisal and delivery of mega infrastructure projects premised on past business-as-usual (BaU) practices. Having revealed how important aspects of the concept of the global infrastructure gap and its metrics are not fit-for-purpose as currently deployed, and in the light of the huge appetite world-wide to invest in more and ever larger megaprojects (Sol Citation2019), it is hoped that such discussion will stimulate further debate, moving the field forward in a more enquiring and context sensitive manner that explicitly embraces sustainability imperatives.

1.2. Defining infrastructure

It is perhaps useful to start by differentiating between the physical and non-physical aspects of infrastructure. The former is typically represented by recognisable boundaries. For example, in the railway sector the physical infrastructure systems are the tracks plus the stations and depots required for the system to function as a network. One can also identify physical elements of the services that operate on and support the railway system, namely the rolling stock and the related land/real estate fixed assets hosting ancillary services and logistic operations. As regards non-physical aspects, again using the railway sector for illustrative purposes, one can point to the institutional infrastructure systems that support the management, regulation and control of the services in question, including the information and communication technology (ICT) software systems.

Physical infrastructure as described above is sometimes referred to as ‘hard infrastructure’ and the non-physical infrastructure as ‘soft infrastructure’. This categorisation should not, however, be confused with an alternative use of the terms whereby physical infrastructure assets, such as those of the transport, water, energy and real estate sectors are frequently referred to as ‘hard infrastructure’, while the physical infrastructure assets of the health, education and social welfare sectors are referred to as ‘soft infrastructure’. We do not intend to take a position here regarding this debate but merely point out that these different perspectives are often a source of confusion, misunderstanding, mis-analysis and debate among different stakeholders.

Irrespective of which terminology one ultimately employs, it is imperative to appreciate that in terms of transformational capacity, i.e., from an ‘agent of change’ perspective, all infrastructure categorisations possess their own potentials through the technological and institutional innovations they employ and promote to transform the physical systems they support, as well as the geographical areas, communities and economies they traverse and serve. Such features are particularly evident in the case of large-scale infrastructure investments, which may be seen as potential hosts, platforms and generators of innovation. What also needs to be appreciated is that these transformational capacities are in turn very much informed, influenced and determined by changes in context beyond the physical dimensions and boundaries of the megaproject (OMEGA Centre Citation2012). These include developments in policy, technology and socio-economic responses to economic and environmental challenges, which can individually or collectively have significant impact on the performance of infrastructure projects and how well they may be judged successful or otherwise.

Contextual changes of the kind alluded to above can sometimes take place dramatically and with great speed, and at other times more incrementally and slowly. Where changes are slow as a result of efforts by particular stakeholders to resist change, they may be seen to congeal and constrain innovation (Graham and Marvin Citation2001; Graham Citation2010). This can be seen, for example, where outdated and out-of-step institutional management traditions and practices shun new developments and merely adapt incrementally to technological progress, rather than seek to embrace change to enhance performance more holistically. To explain more fully why these more constraining outcomes occur is too complex to elaborate here, although aspects are covered in the later discussion about the influence of ‘the power of context’ on decision-making. Suffice to say that the causes of the reticence to adapt and embrace change can sometimes be attributed to matters of affordability as perceived by the stakeholder(s) in question; whilst at other times it can be attributed to ideological and/or economic positions held by influential parties who see that infrastructure should be financed, managed and operated in a particular way, more akin to past practices with which they are familiar.

1.3. The global infrastructure gap

The concept of the global infrastructure gap – presented here as the difference between estimated future world-wide infrastructure needs and current global investment levels in infrastructure - was perhaps most effectively brought to the attention of the world by the McKinsey Global Institute (MGI) in the publication of two reports, namely, Infrastructure Productivity: How to save $1 trillion a year on infrastructure productivity (MGI Citation2013) and Bridging Global Infrastructure Gaps (MGI Citation2016). The concept has since been used widely by numerous international bodies, including: international financial institutions (IFIs), multilateral development banks (MDBs) and other development agencies; the United Nations (UN) and its agencies; the World Economic Forum (WEF); the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD); many governments; and innumerable private sector parties, including international investors and construction companies, as well as many technical and management consultancies involved in international infrastructure development. The perceived gap is frequently used to justify the need to urgently invest in infrastructure world-wide on the premise that such investment will enhance economic growth and development. It is also increasingly employed to draw attention to the opportunities and benefits of private sector involvement in plugging the perceived gap (Sol Citation2019).

Before proceeding to any consideration of the size and nature of the global infrastructure gap, it is necessary to briefly address a problem with the debate around the concept because of the tendency of some analysts and commentators to use the terms ‘need’ and ‘demand’ interchangeably, and to compile their statistics by conflating the two.Footnote2 Whilst there is a clear need to deliver quality and purposeful infrastructure such as shelter, access to clean water and electricity etc. to enable communities to survive, the provision of a high-speed rail network is often more aspirational than essential and an infrastructure asset that some governments and societies believe they can afford, seeing it as a strategic pre-requisite for their economies to prosper. It is important to draw such distinction, especially in developing economies, because failure to deliver on what public policy considers to be acceptable minimum standards of infrastructure provision of essential needs and services, and good access to these to ensure a reasonable quality of life, is what we contend determines the ‘real infrastructure gap’ that should inform investment priorities but which all too often does not.

The 2016 MGI document indicated that at the time of its publication the world was investing some US$2.5 trillion a year in transport, power, water, and telecommunications systems, referred to collectively as ‘economic infrastructure’. Based on an average global GDP growth rate of 3.3 percent, the authors of the report forecasted an aggregate spending of US$49.1 trillion between 2016 and 2030, representing 3.8 percent of GDP. It furthermore identified a global need to invest an average of US$3.3 trillion annually in infrastructure, with emerging economies estimated to account for some 60 percent of that need (MGI 2016). Concluding that current levels of investment were woefully inadequate to meet ever-expanding global infrastructure needs, the authors of the report warned that this deficit ‘contributed to a lower economic growth globally than could have been otherwise achieved and that these shortages deprived citizens of essential services’ (MGI Citation2016, preface).

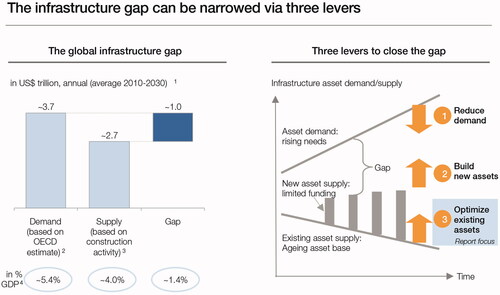

The OECD (Citation2017) arrived at a somewhat higher annual infrastructure spend requirement. It did so by including ‘social infrastructure’ needs in the calculation. Reported in a WEF publication prepared in collaboration with The Boston Consulting Group entitled Strategic Infrastructure Steps to Operate and Maintain Infrastructure Efficiently and Effectively (WEF Citation2014), these OECD estimates pointed to annual investment need of US$3.7 trillion up to 2030, representing 5.4 percent of GDP. Premised on construction activity estimates of US$2.1 trillion per annum (representing approximately 4 percent of GDP), this same source concluded that there was at the time of its publication a US$1 trillion annual global infrastructure investment gap, representing an estimated 1 percent of GDP.

In response to the initial identified deficit, the authors of the 2014 WEF Report argued that governments have essentially three strategic levers at their disposal to address the resulting challenge, namely: to reduce infrastructure demand; to build new assets; and to optimise existing infrastructure assets (see ). Of these levers, they argued that reducing the demand for infrastructure services is ‘only sometimes a viable option’ and only if user needs for essential public services can be satisfied in other ways. As regards building new assets (the most commonly advocated option), they point out that this is ‘resource-intensive, complex and prone to delays’ and thus unappealing, especially in circumstances where budgets are tight and the availability of long-term loans is limited. They describe the third option (optimising existing infrastructure assets), as largely ‘underexploited, particularly in terms of upgrading existing assets’, including retrofitting. The report presents this last alternative as the one which most helps make such assets more effective, resilient and affordable for investors and users. The same source contends that this third option is too often ‘neglected by policy-makers’, although recently it has attracted more attention given the prevailing contexts world-wide of ‘constrained finance, ageing facilities and rising demand’ (WEF Citation2014, 15).

Figure 1. The global infrastructure gap and a strategy to address it.

Source: WEF (Citation2014, 15).

Responses of a more financial kind have been offered by the international accounting community in a more recent report entitled How Accountants Can Bridge the Global Infrastructure Gap: Improving outcomes across the entire project life cycle published by the Association of Chartered Certified Accountants (ACCA) (Metcalfe and Valerie Citation2019). The document predicts that the global infrastructure investment gap will grow to US$14 trillion by 2040 and not surprisingly observes that ‘as the barriers to bridging the gap vary by country, there is significant variability in the capacity of governments to respond’ (Metcalfe and Valerie Citation2019, 7). This has an inevitable bearing on the deliverability of the options of the kind highlighted by the 2014 WEF Report and is particularly pertinent for government monitoring and oversight of mega infrastructure project developments. Reinforcing these concerns, the same source reports that the major barriers to meeting infrastructure needs include deficits in political leadership, a lack of finance or funding, inadequate planning, and regulatory barriers; findings that echo those reported in the OMEGA 2 Project (OMEGA Centre Citation2011).

As influential as the concept of the global infrastructure gap has been in efforts to better understand infrastructure investment needs globally, and as useful as the concept may initially appear in helping to inform infrastructure development strategies of the kind advocated by the 2014 WEF report, we contend that it is especially timely now to re-visit and scrutinise the premises of both the concept and the metrics it employs. We argue this given the extensive traction that the narrative surrounding the infrastructure gap concept has attracted and the dramatic changes prevailing world-wide regarding geo-political, economic, technological, social, and environmental developments, with those related to climate change and inequity rapidly emerging as the most profound.

Rather than simply taking issue with detailed aspects concerning the infrastructure investment gap estimates or questioning the metrics used in their support, we here press the case to examine key assumptions underlying the figures that frame the arguments presented in light of current global developments. We do this by cross-referring to a number of selected published international reports that point to critical prevailing challenges and provide evidence of major international development shifts that will inevitably have an impact on global infrastructure investment deficits and how they should be identified and estimated. In doing so, we question how appropriate current priorities are for tackling infrastructure deficits when set against advocated UN visions and its sustainable development goals (SDGs) under different scenarios, particularly those related to climate change, carbon footprints and equity disparities. Our scrutiny seeks to highlight the most significant of the findings derived from these recently published reports with a view to offering a more strategic and robust framing of responses to 21st century infrastructure investment challenges for megaprojects, as compared to those framings employing conventional approaches more attuned to delivering development paradigms that invariably promote economic growth goals above all else.

Our stance advocates the inclusion of social infrastructure investment costs (for education, health, welfare etc.), which the MGI estimates largely exclude. The inclusion of these social investment needs is more in tune with OECD infrastructure deficit estimates. This perspective additionally advocates the incorporation of essential environmental protection and governance systems’ costs that support the planning, delivery and operation of the infrastructure hardware and related services over and above technological software systems, with the latter increasingly believed to have the potential to significantly alter, disruptively or otherwise, infrastructure gap estimates. While the costs and benefits of social and technological infrastructure system needs (including software programme systems) are much more difficult to quantify as compared to economic infrastructure, what is clear is that the incorporation of all these elements will significantly increase infrastructure investment gap estimates. However, before delving into these aspects further, a brief discussion ensues as to why this article focuses on mega infrastructure investments, albeit that we on occasion use OMEGA Centre findings on MTPs to illustrate the points being made.

2. Mega infrastructure projects

2.1. What is meant by a mega infrastructure project?

Mega infrastructure projects are by definition very large and typically very costly investments, and may be found in all infrastructure sectors. They are usually complex, more so in some sectors than others, and almost always involve multiple stakeholders. Megaprojects are considered by many infrastructure specialists to be a different breed of project (Capka Citation2004) warranting particular attention in light of their special features, including the extent and reach of their outcomes/impacts, and longevity. The use of the term ‘mega’ implies a scale that is very large in relation to other projects, particularly in terms of the space/height/length of the physical infrastructure in question and/or in terms of the sums of money and other resources involved in their delivery. While the price tag of such investments is by no means the sole or even most important determinant of what is mega, we here employ a definition that assumes a minimum construction cost threshold of US$1 billion.

A further definitional consideration worthy of scrutiny is the use of the term ‘project’ in the context of megaprojects. This is because many infrastructure investments cited as megaprojects are strictly speaking neither mega nor projects. They are instead often programmes of infrastructure developments, comprising numerous sub-projects and initiatives of different scale that collectively cost more than US$1 billion and therefore satisfy the megaproject definition. In these terms, the differentiation between projects and programmes is all about geographical, sectoral and institutional boundaries, each with their own set of stakeholders and agendas. Apart from the ambiguities these definitional issues raise and irrespective of the terminology, what is clear is that the larger the infrastructure investment and the broader its boundaries, then typically the greater the number and diversity of stakeholders involved and affected.

2.2. Why are mega infrastructures important?

The logic for the focus of this article on mega infrastructure investments lies in ‘the new wave of large-scale infrastructure projects financed all over the world…as the main drivers behind the global infrastructure agenda’ (Sol Citation2019, 1). This development reveals an unprecedented number of megaprojects being planned and built of late,Footnote3 despite the considerable challenges they pose on account of their increased size, costs, complexities and often negatively reported environmental impacts.

The reasons for this spate of mega infrastructure investment globally are many and varied. An insightful generic explanation of this growth was offered at the beginning of the new millennium by the Snowy Mountain Engineering Company (SMEC) in its publication entitled The Management of Megaprojects in International Development (SMEC Citation2001, 2), which attributed the growth to the prevalence of:

The ‘big fix’ mentality, where development planners and political leaders alike are attracted to projects that offer a single solution to massive problems.

The continued need for symbols of national development, where megaprojects are interpreted as tangible expressions of national aspirations for economic and social development.

Technological advancements that have facilitated the implementation of projects that previous technologies could not before deliver.

An enhanced global institutional capacity developed by global corporations affecting the attitudes of government decision-makers as to the size of projects, encouraging larger projects to be built.

An increased inter-dependency of megaprojects, where they form part of an economic and technological system whose optimum efficiency is deemed achievable only if complemented by another megaproject investment.

An enhanced global financial network of banks and entrepreneurs, facilitated by global IT arrangements capable of moving funds from one part of the globe to another, literally in an instant, where they were not previously able to do so.

The more recent publication by Sol cited earlier argues that such projects are increasingly being financialised i.e., ‘turned into a financial asset class by international financial institutions’ in many cases to the detriment of wider concerns where/when they pose ‘massive risks, from detrimental climate impacts to debt burden for emerging economies’ (Sol Citation2019, 1). While aspects of this critique have been alluded to for several years (see for example Dimitriou Citation2005, Citation2009), this trend has become increasingly evident since the global financial crisis of 2008, following which supporting narratives appeared to often misleadingly present many mega infrastructure projects as obvious answers to addressing prevailing infrastructure challenges, particularly in the transport sector.

The fact that the activities of international financial institutions (IFIs) and sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) are becoming the dominant force behind many large-scale infrastructure investments has also raised concerns in some quarters, particularly given that the persuasive narratives they employ are often so superficially cogent and alluring in emerging economies and the developing world (Leigland Citation2018). This is especially the case among those who see such investments as public assets that should give priority to linking the territories they traverse and serve for the public good (Graham and Marvin Citation2001), in contrast to those viewing them primarily as strategic opportunities to create or maintain competitive advantage in their efforts to survive and prosper given the reach and increasing pace of globalisation (Porter Citation1990; Castells Citation1996). Parties who support this position contend that infrastructure is not only ‘about bricks and mortar …. (but also, about) systematic wealth extraction from local communities’ (Sol Citation2019, 1), thereby emphasising a ‘winners’ and ‘losers’ dimension in the investment equation.

2.3. Why are they built and for whom?

A critical examination of the winners and losers of mega infrastructure investments and the different calls for such projects to be built can offer invaluable insights into understanding why they are constructed, for whom they are built, and the way they have been financed and designed. While O'Brian and Leichenko (Citation2003) offer some interesting insights into how the winners and losers might be framed in the context of global change, generalising here how one should frame a winner and loser study of mega infrastructure development is of course near impossible given differences in sectors, locations, purposes etc. Nonetheless, it should be noted that any measures a government takes to help one or more parties or geographical areas, implicitly disadvantages those groups/areas not selected (Porter Citation1990).

It should also be noted that the rhetoric of mega infrastructure project promoters rarely refers to project losers. More typically, it is often suggested that everyone gains from such investments in the long-run, either directly or indirectly through trickle-down economic impacts, with the benefits framed in terms of those that accrue to the public and/or are brought to the market as a result of the investment. This stance persists despite evidence and supporting narratives to the contrary offered by well-respected sources such as The Economist (Citation2009), Judt (Citation2010) and Piketty (Citation2014), all of which have demonstrated that these promises often fail to materialise. Times are changing, however, as reflected in the Brookings Institution’s recently published analysis of the winners and losers of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) (Gill, Lall, and Lebrand Citation2019). This follows a World Bank Study of the opportunities and risks of the BRI (World Bank Citation2019), a topic that we will return to.

Promoters of mega infrastructure projects frequently talk about ‘stakeholder engagement’, an underlying principle of which is that stakeholder parties ‘have the chance to influence the decision-making process’ (Jeffery Citation2009, 18). Meaningful stakeholder engagement, however, requires understanding and a need to differentiate more clearly between the engagement process itself and the rhetoric of the stakeholder communications processes, where the latter’s underlying agenda often seeks to persuade affected parties to agree with decisions already made by a project’s promoter(s). What both exercises are frequently less prone to do is to reveal who the stakeholders are beyond those involved in project delivery – except perhaps in a tokenistic manner that at best reveals a hierarchy of stakeholders who matter, and excludes those who do not. This is possibly the first step in a project’s winner and loser designation. What is evident, however, is that the demand for large-scale infrastructure projects is derived from a variety of usually influential stakeholders lobbied for by numerous parties, each with their own agenda and set of priorities, which inevitably injects a further level of complexity and tension into the decision-making for such investments, particularly in the developing world (Hemmati and Rogers Citation2015).

In the most straightforward cases, mega infrastructure projects are presented as responses to a clear demand. For example, a proposed MTP responds to the travel demand of persons (passengers) and/or goods and raw materials (freight). When supporting projects of this kind, politicians often promote such investments as strategic catalysts of economic growth that will transform the economies they traverse for the better. Sometimes, sadly, they are promoted out of a combination of self-interest and realpolitik (Altshuler and Luberoff Citation2003) to support overtly commercial priorities that may not necessarily dovetail with the public interest. Megaprojects are also on occasion hailed as icons of progress and modernisation, particularly in developing regions and economies in need of stimulus. Meanwhile, depending on the planning regimes in place, they are often used to reinforce or lead other plans and investments as part of larger national/regional development strategies, possibly with trans-national dimensions (OMEGA Centre Citation2012).

Identifying and understanding who ultimately funds, finances, owns and operates mega infrastructures and why, and how these responsibilities may have changed over time and for what reason, reveals yet another layer of complexity in the anatomy of mega infrastructure investment decision-making. These considerations have a significant contextual bearing on how well such investments are seen to perform as agents of change by different stakeholders, as well as the criteria employed for judging their success. Whether a call for a mega infrastructure investment is initiated at the international, national, or regional/local level also matters, as does whether it benefits from the sustained support of political champions (OMEGA Centre Citation2012). The rationale(s) employed by representatives of these various parties and the powers of influence they exert, both historically and at the time of their presentation for political ratification, inevitably frames the balance of public and private sector funding and risk-sharing that is ultimately agreed and, subsequently, any prospect of the use of public-private-partnerships (PPPs) as a vehicle for their procurement and delivery.

2.4. Emerging issues

What is clear from emerging international evidence is the widespread inadequacy of the governance and institutional capacities in place at all levels for infrastructure development (Papakonstantinou Citation2019). These deficits apply to both the public and private sectors, attributable in the former in large measure to inadequate resourcing and training. The severity of these constraints is so great that they are now globally acknowledged as a major obstacle to the development and delivery of infrastructure needs, in some cases irrespective of the affluence of the economies in question. Linked to this is a belated and growing recognition that such constraints compromise any satisfactory accommodation by governments of project finance and other forms of private sector-led mega infrastructure delivery (WEF Citation2014; MGI Citation2016).

Institutional and governance capacity deficiencies are accentuated by broader influences and forces at play that have encouraged and perpetuated retrenchment in the role of the state in infrastructure provision per se, promoting greater de-regulation, more out-sourcing, and an increased dependency on private sector participation and finance in infrastructure development. These changes have been supported by a powerful neoliberal narrative suggesting that such measures deliver leaner and more efficient public services and introduce more safeguards against the perceived inefficiencies and associated excesses of the public sector (Hodge and Greve Citation2019). Paradoxically, the changes have in many cases proven to be to the detriment of delivering megaprojects on time, to cost and to specification (the so-called ‘iron-triangle’ criteria), because the institutional deficiencies in the public sector have undermined the ability to effectively deliver PPPs in partnership with the private sector beyond the rhetoric (Ward et al. Citation2019).

As other global forces have come to prominence, so the context for judging infrastructure as an effective agent of change is altering dramatically. Past thinking and practices are increasingly being challenged and are seen to generate additional major risks and uncertainties not previously adequately recognised (European Court of Auditors Citation2018). In this sense, it is argued that neoliberalism has become part of the problem rather than the solution, because it limits holistic perspectives from being employed in line with delivering on the goals of sustainable development. Furthermore, decision making is being compromised as neoliberal values permeate many of the BaU approaches to mega infrastructure investment, notwithstanding increasing concerns for corporate social responsibility (CRS), public consultation and environmental impacts. The net result is much less transparency about winners and losers of infrastructure development (Locatelli et al. Citation2017), which has the potential to cause resentment by those not seen to have benefited adequately from such investment. This is particularly the case when such parties carry a disproportionate share of the burden of these investments and when the projects are funded from the public purse.

Another concern is the longstanding prevalence of the ‘predict and provide’ mentalities adopted by the infrastructure industry, especially in the transport sector (Adams Citation1981; Gouldena, Ryley, and Dingwall Citation2014). These mentalities frame much of the infrastructure industry’s thinking about the global infrastructure gap and related infrastructure deficits on the basis of estimates derived from trend projections in a largely path-dependent manner (Curtis and Low Citation2012). This practice has often incrementally embodied outdated 20th century infrastructure technologies, as well as 20th century values and lifestyle behaviours, as responses to 21st century challenges. This despite the fact that in some/many cases: new technological innovation threatens to make redundant or at least disrupt current technologies (Guy, Marvin and Moss Citation2001; Graham Citation2010); new global environmental challenges are unfolding at a scale, severity and geographical coverage not witnessed before (UNEP Citation2012); and inaction and short-term responses to critical global and more local economic challenges are in danger of generating unstable political environments that jeopardise provision of urgently needed infrastructure that would otherwise promote sustainable development (OECD Citation2017).

Drawing on the findings of selected international reports that the authors consider germane to many of the issues raised thus far and research findings from the OMEGA Centre, the discussion in the following section offers some strategic insights into why and how the prevailing global infrastructure gap concept and associated estimates of infrastructure deficits need to be reframed and revised, and made more robust in light of the new global development realities.

3. Changing contextual landscapes

3.1. The need for re-framing

The underlying premise of this article is that the global infrastructure gap and related infrastructure deficits as conceived by MGI, employed by others, and currently presented in the international literature, presume certain assumptions and trends that are either no longer valid, or have already altered so dramatically that the recommendations they produce cease to be fit for purpose given prevailing and emerging changes in context. It is our contention that if one takes on board meaningful consideration of the UN’s vision of sustainability and its related development goals (SDGs), the resultant infrastructure investments occasioned by inappropriate BaU proposals, are likely to accentuate the severity of many problems rather than resolve them; and in the case of mega infrastructure, this is most likely to be more pronounced as such projects become larger and more complex.

Building on the preceding issue analysis, the text which follows presents material that the authors believe significantly informs and supports the case to reframe how global infrastructure needs are estimated and the role of megaprojects within this effort. While it is conceded that we could have drawn from innumerable other publications relevant to the case we are presenting, we focus on five selected sources that have both informed our analysis and aspects of the findings arrived at by the OMEGA Centre study of decision-making in the planning, appraisal and delivery of MTPs (Dimitriou, Ward, and Wright Citation2013) (see ). Drawing on these sources, certain common strategic fundamentals are identified that, if pursued, have the potential to transform the current concept and narratives about infrastructure gaps and needs into a more suitable framework for addressing 21st century sustainable infrastructure development challenges. These are seen to have the capability to beneficially inform and guide not only the development of proposed new-build mega infrastructure investments but also the retrofitting of existing megaprojects that need to be made more resilient to emerging threats and developments, and more innovative in their deployment to better exploit new technological opportunities.

Table 1. Lessons from the OMEGA Centre Case Studies of 30 MTPs.

3.2. Trawling critical lessons from selected publications

The five publications considered to be of special relevance to informing the re-framing of the global infrastructure investment gap thesis in addition to the OMEGA Centre findings, include:

Baghai, Coley, and White (1999) The Alchemy of Growth;

United Nations (Citation2015) Transforming Our World: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development;

IPCC (2019) The Inter-governmental Panel on Climate Change Report;

Hall (1980) Great Planning Disasters; and

WEF (2019) The World Economic Forum Global Risks Report.

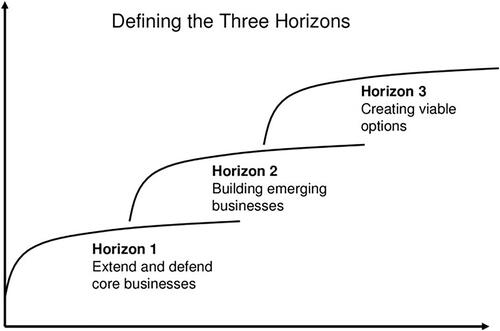

3.2.1. The Alchemy of Growth

The Alchemy of Growth by Baghai, Coley, and White (Citation1999) presented what has become known as McKinsey’s Three Horizons of Growth Concept (see ).Footnote4 Arrived at by a team of researchers commissioned some 20 years ago by McKinsey Consultants to investigate how a company with international corporate reach can survive global competition in a fast-changing world, this concept has direct relevance to infrastructure investment planning. It concluded that successful businesses need to have in place simultaneously active projects in each of the three horizons of development of their business - in the short run (1–5 years), during the mid-term (5–15 years), and for the long-run (15 years and beyond) - to ensure sustained growth and success in order to allow the company to fund speculative projects for the future from present day successes, with the most critical and challenging phase being the mid-term when transitioning from horizon 1–3 (Baghai, Coley, and White Citation1999, 5).

Figure 2. The three horizons of growth concept.

Source: Baghai, Coley, and White (Citation1999, 5).

The implications of the above principles for mega infrastructure investment, the global infrastructure gap thesis and its ramifications are numerous and significant. Before addressing these, however, it is pertinent to point out that the Horizons of Growth Concept also has some association with the principles presented by The Brundtland Report (WCED Citation1987). Brundtland developed the early guiding principles for sustainable development, defined as ‘development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’ (WCED 1987, 5). The association lies in the fact that both seek to link the present (BaU practices in particular) with future aspirations or visions, employing a strategy that acknowledges the importance of understanding current investment practices and the extent these should be moved in a transition phase toward a more desired future.

As earlier indicated, forecasts to identify infrastructure gaps and related infrastructure deficits are typically calculated on a ‘predict and provide’ basis. This approach, which presumes a correlation between additional infrastructure capacity and increased prospects of economic growth, typically employs forecasts based on narrowly framed path-dependent estimates. In the transport sector, this involves adopting market-led travel and transport demand behaviour assumptions derived from past socio-political and economic trends and contexts, with a limited use of scenario scrutiny. In contrast, strategies and plans for sustainable development introduce policy-led standards and values into investment decision-making that seek to protect and regulate the communities and environments they serve against the excesses of market forces. In doing so, such strategies and plans look to decouple infrastructure investment from economic growth outcomes that are agnostic of broader sustainable development concerns regarding climate change, carbon footprints, and social equity and poverty alleviation challenges.

While it is readily apparent that McKinsey’s Three Horizons of Growth Concept and the principles of sustainable development as articulated by Brundtland differ significantly in terms of their respective visions and the ends towards which each advocate that effort should be invested, what is less evident is their potential useful application to the global infrastructure gap thesis and the critical role of technological innovation in developing options for the future, which features in both. Failure to acknowledge and exploit new technological innovations could, as earlier indicated, unwittingly contribute to building 21st century infrastructure based on 20th century technologies and investment practices that are out of sync with the new and emerging development contexts. This fear has particular resonance for large scale infrastructure projects, where there has long been a reluctance to use new technologies that are not fully tested and therefore more high risk. Notwithstanding such concerns, it is argued here that if one could dovetail positive elements of the McKinsey and Brundtland approaches with the UN sustainable development vision and its metrics more appropriately – i.e., decoupled from the priority afforded to economic growth by the prevailing infrastructure gap thesis - and simultaneously embrace the new contextual forces that highlight the urgent need for more holistic approaches to development challenges, there is considerable scope for the reframing of estimates of global infrastructure needs and deficits in line with sustainable development principles.

3.2.2. The UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development

The UN’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development Report of 2015 first presented the collection of 17 inter-connected global development goals set for delivery by the year 2030. The so-called Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are scions of the eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) declared at the UN Millennium Summit of 2000 that were set to be achieved within 15 years and which they have now superseded. Four years after the adoption of the SDGs, the 2019 UN SDG Report concluded that significant progress had been made in some areas, such as ‘extreme poverty reduction, widespread immunisation, decrease in child mortality rates and increase in people’s access to electricity.’ It warned, however, that the response has overall been inadequate, with the vulnerable likely to suffer the most (United Nations Citation2019, 38). Of the four key findings of this report – i.e., increasing inequality among and within countries, poverty alleviation, global hunger, and climate change - climate change emerged as the most challenging and potentially most serious. This was reinforced by the fact that ‘2018 saw the fourth warmest year on record, with levels of carbon dioxide concentrations continuing to increase’ (United Nations Citation2019, 48). Given the potentially devastating global ramifications of this failure to rein in global warming, the same source reports that in the event insufficient action is taken, not only will the poorest suffer the most but recent SDG progress will be reversed. It also highlights the inevitability of significant territorial disruption, especially to island economies and coastal areas. Such developments would seriously undermine continuing attempts to deliver the SDGs, and any collective efforts to make economic productivity more sustainable both locally and globally.

What was very apparent at the time of reporting on the MDGs, and later when reviewing the progress made in delivering the SDGs, was the significance of the interrelationships among the respective goals and the high dependence on infrastructure systems of all kinds in facilitating such interconnectivity and ultimately enhancing their performance. This strategic role of infrastructure highlights its importance as both a potential midwife and also steward of development. Based on such understanding, it is clear that the successful delivery of the SDGs relies in large measure on infrastructure and, on reflection, it is surprising that infrastructure was not included as an explicit area of concern for the original MDGs.

Of the current 17 UN SDGs, Goal 9 – entitled ‘Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure’ – declares infrastructure and innovation as ‘crucial drivers of economic growth and development.’ It cites the fact that more than half of the world’s population of approximately 7.7 billion currently live in cities and that, as a result, the adequacy of the spread and performance of public transport and renewable energy systems etc. have become increasingly critical to the successful delivery of all the SDGs (United Nations Citation2019, 40). The 2019 report also flags the importance of technological progress when addressing economic and environmental challenges, so as to generate new jobs and deliver cleaner energy more efficiently in support of more sustainable industries. It further stresses the importance of investment in scientific research and innovation to help deliver more strategic ways to facilitate sustainable development. To illustrate the importance and scale of infrastructure investment needs in the delivery of sustainable development, the same source highlights the fact that 2.3 billion persons worldwide lack access to basic sanitation, and that in some low-income African countries, infrastructure deficiencies can cut business productivity by up to 40 percent. Meanwhile, of the ‘4 billion people still not having access to the Internet, 90 percent are from the developing world’ (United Nations Citation2019, 57). Bridging this digital divide is crucial to ensuring equal access to information and knowledge, as well as fostering innovation and entrepreneurship.

The arguments above represent a very different expression of critical concerns about infrastructure deficits to that presented by the MGI concept of the global infrastructure gap. The UN’s perspective is offered through a spectrum of SDGs contributing to a shared overall vision of sustainable development that the UN promotes. Unlike the MGI estimates of infrastructure deficits that are essentially path dependent in character, the SDG framed estimates are derived from more normative dimensions that relate to on-going UN policy frameworks and associated metrics in response to broader interconnected global development challenges beyond the needs of the market. Despite the fact that broader sustainable development approaches to calculating infrastructure needs and deficits are still in their infancy, they are rapidly gaining currency and attracting international attention as potential platforms for producing more resilient outcomes. While there are numerous such approaches being developed world-wide, the following four about which we have particular knowledge are offered by way of illustration:

The STAR appraisal framework for sustainable infrastructure investment developed and promoted by the Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) led by the Asian Development Bank (ADB) (ADB 2014). This is the product of a working group on sustainable transport given the task of developing a common assessment framework, which proposed Sustainable Transport Appraisal Rating (STAR) as a tool for assessing the sustainability of ADB’s transport projects and for monitoring changes in project portfolios. It was also developed as a contribution to an emerging common assessment framework of the eight MDBs participating in the working group for potential application to all infrastructure sectors.

The Policy-Led Multi-Criteria Analysis (PLMCA) framework/process for appraising megaprojects developed by the OMEGA Centre. This was initially developed from work undertaken for the Institution of Civil Engineers (ICE) and Actuarial Profession (AP) in the UK (OMEGA Centre Citation2010), the outcome of which recommended the use of a policy-led multi-criteria as a means to better incorporate risks and uncertainties in decision-making, and better embody environmental and social dimensions of sustainable development throughout all stages of the project cycle, especially for the appraisal process (Ward, Dimitriou, and Dean Citation2016). The approach highlights key stakeholder interests, integrates the use of different appraisal tools, identifies which criteria are important/appropriate by stakeholder category and which should receive priority in line with policy and resource scenarios, and facilitates how trade-offs between tangible and intangible criteria are best made in a more transparent manner.

The Ecological Sequestration Trust approach to sustainable infrastructure investment developed by Peter Head and his team at the Ecological Sequestration Trust (The Ecological Sequestration Trust Citation2016). This offers a roadmap for delivering SDGs by 2030 in the world’s city regions based on an open source information/data sharing platform and a core set of tools for use by multiple stakeholders, enabling the planning and financing of resilient infrastructure for sustainable cities. Designed as an analysis and decision-support tool for collaboration and resilience decision-making for different stakeholders, it contains a growing library of process models of typical human, industrial and ecological systems intended to connect to many international and local data sources, including from earth observation satellites, government and private sector data bases, local sensor networks, smart phones, tablets and local survey data.

Waage et al. (Citation2015) presentation of the Health and Well-being SDG (Goal 3) and its interactions to others as they affect infrastructure. The authors report on a review involving experts in different SDG areas who identified potential interactions through a series of workshops. At these events, the experts generated a framework that ‘revealed potential conflicts and synergies between goals, and how their interactions might be governed’. Explaining ‘these (health and) well-being goals are supported by second-level goals that relate to the production, distribution, and delivery of goods and services’ they refer to them as ‘infrastructure goals’ (Waage Citation2015, 251). We consider that there is considerable merit in re-framing MGI’s infrastructure deficits in a similar way.Footnote5 Given these deficits are focused on economic infrastructure, essentially delivering economic growth, their re-positioning to other goals in an equivalent form could well generate new valuable frameworks of costs and benefit, revealing potential conflicts and useful synergies between goals otherwise not identified.

3.2.3. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Report

Cross-referring in part to the SDGs and framing perspectives on global infrastructure developments across all sectors, the 2019 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) explores how the way we use our land globally contributes to climate change and how this in turn affects both the land and the world’s development overall. While the report’s coverage is broad, it has four key findings: certainty that human activities are responsible for global warming; the present critical levels of carbon dioxide; the rising sea levels; and the dramatic receding of the world’s ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica (IPCC Citation2019, 1).

As a 2019 special issue of The Economist on climate change explains, the developments referred to in the IPCC report owe much of their origin to ‘the remarkable growth in human numbers and riches that stem from the combustion of billions of tonnes of fossil fuel to produce industrial power, electricity, transport, heating and, more recently, computation’ (The Economist Citation2019, 13) … and that all are infrastructure related. The same source asserts ‘that changing climate touches everything and everyone and should be obvious, as it should be that the poor and marginalised have most to lose when the weather turns against them. What is perhaps less obvious, but just as important, is that because the processes that force climate change are built into the foundations of the world economy and of geopolitics, measures to check climate change have to be similarly wide-ranging and all-encompassing’ (The Economist Citation2019, 3).

Since mega infrastructure assets typically occupy important strategic tracts/corridors of land in cities, regions and across nations, and because the activities they support and generate have impact on multiple concerns of the IPCC Report, it is clearer today more than ever that to effectively mitigate the worst aspects of climate change one needs to employ holistic approaches to infrastructure investment planning and appraisal. This is a stance echoed by the same issue of The Economist, which also lamented that the market economy has thus far done little to help introduce the much needed ‘near-complete overhaul’ of investment practices that fail to be holistic (The Economist Citation2019, 13), simply reinforcing the case made in this article of the need to reframe the global infrastructure gap thesis and address perceived deficits in a more comprehensive and integrated fashion.

Influential political champions can have significant influence in informing and driving public policy to limit global warming but, in the political space we currently find ourselves, politicians are too divided or too slow to take the necessary action. This has allowed many BaU interests to plough-on with new mega infrastructure developments on a bigger scale and with more complex technologies, albeit sometimes coated with a thin ‘green’ veneer. Many as a result, we contend, will ultimately leave even larger brown footprints than they replaced or generate outcomes of which we have untested/uncertain knowledge. Given these circumstances, we argue that there is a clear need to effectively mitigate the worst aspects of these infrastructure impacts, not only in the wake of the slowly unfolding climate catastrophe but also in what we see is a dramatic shift currently underway in factors that influence the context of public policy and associated decision-making, with this shift taking place as this publication goes to print. This contextual transformation is being informed by increasing scientific evidence of the damage that climate change is having and the significant and harmful contribution of inappropriate infrastructure to such change, particularly in the transport sector. The growing influence of various media outlets, especially social media, fuelling the clarion call for immediate action to redress the situation is also starting to have an important impact.

3.2.4. Great Planning Disasters and the power of context

The power of changing values in society reframing societal judgements about the success or otherwise of mega infrastructure investments was raised by Peter Hall in his seminal book, Great Planning Disasters, published in 1980. This was well before Malcolm Gladwell re-introduced the concept of the ‘power of context’ in 2000 in very different settings in his book about tipping points in decision-making (Gladwell Citation2000).Footnote6 In presenting his thesis, Hall drew on earlier writings by Friend and Jessop (Citation1969) which identified three kinds of uncertainties that have an impact on judgements about the success of strategic public investments, namely:

uncertainties in the relevant planning environment (e.g., those arising from demography, economic growth etc.);

uncertainties about related decision areas (e.g., in transport and environmental policies); and

uncertainties about the value systems of the relevant project stakeholders (e.g., of governments, investors, NGOs and communities).

This ‘power of context’ argument was also revealed to be highly influential in decision-making regarding many of the 30 mega transport case studies reviewed by the OMEGA Centre as part of its OMEGA 2 Project (OMEGA Centre Citation2011).

Regarding climate change and its impact on the power of context, and how it is increasingly framing judgements about mega infrastructure development, it is important to recognise this is a significant recent dynamic that is currently influenced by the re-emergence and exponential growth of the green movement worldwide, most vividly depicted by Extinction Rebellion protestors. Movements of this kind have emerged in response to both perceived and actual longstanding interference by lobbyists representing BaU interests that all too often support unsustainable developments, frequently with the assistance of the so-called ‘hidden hand’ (Hirschman Citation1967). Of late, suspicions about such circumstances have given rise to growing concerns and public anger about the climate crisis and the inadequacy of mitigating actions thus far. It is our contention that these developments are moulding a new reality, a new realpolitik perhaps, which makes the call for the re-framing of the global infrastructure gap thesis so obvious that it is hard to comprehend rationally how BaU infrastructure investment practices are sustained. We take this view given climate change is predicted by the IPCC to displace tens of millions of people and have a critical and adverse impact on agricultural output globally, as well as contributing to flooding and droughts world-wide, with all that this implies for infrastructure development. This is, however, but one of the cocktails of global risks currently confronting the planet, albeit perhaps the most important, about which future investments in mega infrastructure projects have an important bearing as the ensuing discussion explains.Footnote7

3.2.5. The World Economic Forum Global Risks Report

Placing the challenges of how best to assess and address current and future global infrastructure deficits in the context of the Three Horizons of Growth Concept, the UN’s Vision of Sustainable Development and the IPCC’s Critical Climate Change Challenges provides some very interesting further insights if the discussion is also framed by the power of context argument presented above together with the findings of the two most recent World Economic Forum Global Risks Reports (2019 and 2020). The overarching and somewhat daunting conclusion of the authors of the former of these WEF reports is that prevailing geopolitical and geo-economic tensions if unresolved ‘will seriously hinder the world’s ability to deal with a growing range of collective challenges, from the mounting evidence of environmental degradation to the increasing disruptions of the Fourth Industrial Revolution’ (FIR) (WEF Citation2019, 23), to which one should add, we contend, the need to urgently address the globe’s growing and changing infrastructure needs and deficits. Together, spurred by the FIR, which the WEF predicts will not only fundamentally change how individuals interact but also more profoundly how society functions, we are set to enter into a new stage of development facilitated by major technological advances equivalent to those associated with the first, second and third industrial revolutions.

The landscape of global risks since 2007 shown in and the global risks interconnections discussed in these WEF Global Risks Reports reveal that many/most of these challenges involve, rely on and/or have an impact on infrastructure development, echoing our own assertions and those of other authors cited in this article regarding the important role of infrastructure as a facilitator of change. Given that this engagement with infrastructure has in recent decades increasingly involved larger, more complex and costlier mega infrastructure investments, one may assume that infrastructure development outcomes and influences associated with these developments will commensurately grow. This growth, however, will be accompanied by increasingly uncertain ramifications given the technological, economic, political, societal and environmental global risks of the kinds highlighted in the Figure so prominently.

Figure 3. The global risks landscape, 2007–2020.

Source: WEF (Citation2019, 5)

The negative impact of such uncertainty also pertains to climate change and extreme weather events likely to have adverse impacts on infrastructure performance, not only compromising service delivery by public agencies but also undermining revenue streams and anticipated investment yields for private operators. The introduction of new resilience measures and bolder action is therefore being trumpeted by all parties. In this sense, we argue that the pathway to sustainability is through resilience, and nowhere more so than in the development of both more overtly robust new mega infrastructure, as well as the embodiment of resilience pre-requisites in the retrofitting and modernisation of the existing infrastructure stock.

Scrutinising further the observations and arguments presented by these WEF publications, one of the main messages they convey is that policy makers and key investors would do well to re-consider how they might better navigate their decision-making in the context of what it refers to as a ‘fractious world’. The authors of the 2019 report in particular claim that it is clear that the emerging ‘new political agenda’ and the increasing regulatory uncertainties that result, make it much more difficult for investors and corporations to sustain BaU practices; a point reinforced by the writings cited earlier. From the perspective of such investment parties, these new emerging developments generate uncertainties and realities of their own that inhibit ‘their ability to make crucial business decisions and investments…when opportunities from emerging technologies are demanding boldness and agility’ (WEF Citation2019, 28). This concern is especially worrisome in the case of critical mega infrastructure projects such as major power plants.Footnote8

4. Hindsight and foresight

4.1. Crisis management

Reflecting on the above collage of findings, it is easy to see why a number of commentators (see Friedman Citation2008) have suggested that the world is sleeping-walking into a crisis, albeit with climate change in the vanguard but also on a number of other fronts including infrastructure development. As we have highlighted in the preceding section, the planet faces a growing number of complex and interconnected challenges at the interface of the built and natural environments, where such interdependencies serve to exacerbate the impact of individual threats within an increasingly fragile global ecosystem. Against a backdrop of persistent and growing economic inequality, rising sea levels, extreme weather events, biodiversity losses, crop failure and famine, the severity of such threats and their connectivity is obvious. Urgently addressing infrastructure needs and deficits must necessarily be part of any solution to such problems both collectively and individually. Yet, policy makers continue to embrace too many failed ideas and false promises as nations and their communities appear to move aimlessly and deeper into a labyrinth of global problems from which they might struggle to break free. But as the Chinese adage suggests, where there are threats there are also opportunities including, as we have previously indicated, those afforded by the accelerating pace and global reach of the FIR, notwithstanding the increasing risk of the threats now posed by cyber-attacks to the performance of critical infrastructure (WEF Citation2020).

In addressing these shared global problems, there has rarely been a more urgent need for a collaborative response, a point reiterated by the WEF Global Risks Reports we have cited. In emphasising the need for more collaboration, these publications identify deteriorating issues of global governance as an even greater threat than climate change, since it’s only through a collective will to act appropriately at a global scale that many prevailing global challenges, including and especially the global infrastructure challenge, can be effectively addressed.Footnote9 Meanwhile, the seeming complacency of the world’s major economies in confronting the climate challenge, as reflected in the failure post-Paris 2015 to deliver on meaningful climate change adaption and mitigation, is of concern…yet these and similar climate friendly policy initiatives should be at the heart of any global infrastructure investment strategy.

There is as implied, however, a fundamental problem with this aspiration for more collaboration. Following the increasing integration of the planet’s political economy occasioned by globalisation and its ramifications, the world now appears to be moving into a new period of divergence as more and more politicians exploit the ‘taking back control’ mantra in pursuit of a popular mandate (Baldini, Bressanelli, and Gianfreda Citation2020). How this might ultimately impact global infrastructure development is unclear, except to note that many mega infrastructure investments across all sectors are attracting growing public opposition, and that political risk has now entered the appraisal considerations of many infrastructure developments across the world, and not just in developing economies (Zelner and Henisz Citation2000).

Unfortunately, the energy and resources that are being expended to address such national and domestic issues, and the increasingly state-centred political agendas that they are attracting, are necessarily at the expense of the collective efforts that are required to address the critical global challenges that confront us, including global infrastructure needs and deficits. Moreover, the on-going reconfiguration of previously integrated and convergent economies in response to growing trade wars and dissatisfaction regarding who benefits from globalisation and who does not (Weiß, Sachs, and Weinelt Citation2018), have special implications for future global infrastructure investments as we have already suggested. This is particularly the case for MTPs planned to facilitate integration across international boundaries. From our earlier discussions and issue analysis, these look to be fraught with difficulty if not adequately adapted/retrofitted to the new realities and challenges of the 21st century. Quite what impact this might all have on global infrastructure development is uncertain, except to reiterate that many mega infrastructure investments across all sectors are attracting increasing public opposition, and that political risk now features more prominently in the appraisal of many infrastructure developments world-wide.

4.2. Planning back on the agenda

For much of the early 20th century, the primary objective of economic policy was to facilitate competition and support markets to ensure a supposedly level playing field in the efficient distribution of society’s scarce resources, i.e., laissez-faire. Economic intervention was a public policy instrument that was only reluctantly deployed to address pronounced geographic inequalities within countries and foster spatial integration by investing in public works in poor areas. The Great Depression provoked a re-appraisal of this position, as did the early writings of John Maynard Keynes that culminated in the publication of his seminal work, the General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (Keynes Citation1936). A more proactive role for governments in macro-economic policy was subsequently suggested and, in the period of recovery following the Second World War, a neo-Keynesian synthesis emerged that supported free competition and the role of markets but, crucially, also recognised the importance of state intervention when markets failed (Hicks Citation1937; Samuelson Citation1955). It not only promoted planned investment in essential infrastructure in poor areas to facilitate economic growth and redress spatial disadvantage, but also encouraged infrastructure investment as a contra-cyclical device during economic downturns.

Keynesian economic policies served the developed economies of the so-called first world well and, in the wake of the 1944 Bretton Woods Agreement, were exported to developing and emerging economies by IFIs and international development agencies. The latter all promoted infrastructure-led growth and development, but within a very different policy environment in developing economies that were at that time in large measure insulated from international competition by regulation, import substitution and similar protectionist policies (Kessides Citation1993). Much of the financial assistance on offer was to support infrastructure development, but large infrastructure projects can be very costly and may not in the event promote the desired economic growth and industrialisation. This was the case in sub-Saharan Africa, where the unintended economic, social and environmental consequences of major projects, created unsustainable debt burdens that would subsequently compromise rather than stimulate economic growth and eventually result in sharp economic contraction. In this regard, the experiences of Ghana (Anyinam Citation1994), Nigeria and what was then known as Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo) are particularly instructive, were not properly anticipated and often seriously problematic (Mold Citation2012).

In the 1980s, with the emergence of neoliberalism and following a series of economic crises, the World Bank and other development agencies began to impose more stringent loan and grant conditionalities that obliged developing countries to abandon their interventionist economic planning strategies and to adopt more market orientated policies under the umbrella of what was termed ‘structural adjustment’. This allowed market forces to determine the geographical distribution of goods, services and productive activities. The proponents of the approach, referred to collectively as the Washington Consensus, hoped that by abandoning protectionist policies and implementing painful reforms (including significant deregulation) countries would be forced to concentrate more on trade and production to boost their economies, become more competitive, and attract more foreign direct investment (FDI). Within this paradigm, it was argued that aid would increasingly be replaced by loans and, facilitated by globalisation, developing countries would ultimately move up international value chains before ’taking-off’ into periods of sustained export-led growth (Zepeda et al. Citation2009; Palley Citation2011; Piketty Citation2014). This, it should be appreciated, is largely the context of the global infrastructure gap thesis and related infrastructure deficit estimates, ushering in an increased dependence on international private sector capital oiling the cogs of infrastructure delivery.

In this sequence of events the public sector and its role in promoting development was significantly undermined, weakened and under-resourced.Footnote10 With the recipients of development aid and/or soft loans obliged to follow a rule book informed by an essentially free market ideology, domestic governance structures, already suffering from deficiencies and cut-backs in administrative and technical capacities that we have highlighted elsewhere, were further compromised by the resulting dichotomies and complexities of this new economic order. It is beyond the scope of this article to address the full consequences of this change of policy, presented at the time as a more financially ‘sustainable’ model, but actually not so if scrutinised holistically against more recently articulated UN principles of sustainable development. In some cases, outcomes have been catastrophic, curtailing already relatively modest rates of economic growth and more often than not intensifying existing levels of poverty (Shah Citation2013). The net impact was that infrastructure investment decisions began much more than ever to follow the money, rather than reflecting needs identified by key domestic stakeholders and state sponsors. This has been particularly evident in the transport sector with privatisation initiatives fuelling such development. We suggest that even to this day many economists and other enthusiastic supporters of the neoliberal paradigm struggle to find evidence-based examples of countries that have benefitted overtly from the resulting change in development strategy (Pugh Citation1995; Crisp and Kelly Citation1999; Brown et al. Citation2000).

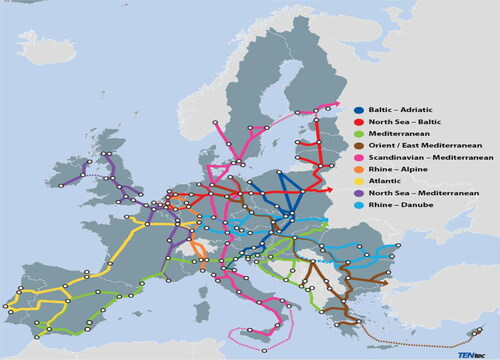

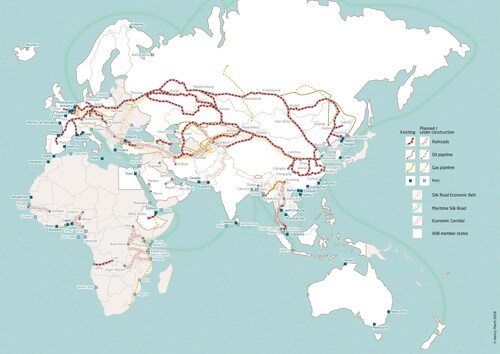

We see the global infrastructure gap thesis and the Belt and Road Initiative’s (BRI)Footnote11 transnational infrastructure development aspirations (see ) as examples of how infrastructure development, particularly mega infrastructure, has been encouraged to continue to follow the money. This has been less the case for the European Union’s (EU) transport infrastructure development aspirations as reflected in its Trans-European Transport Networks (TEN-T) programmeFootnote12 (see ). Although both the BRI and the TEN-T programme are trans-national, what differentiates the TEN-T initiative from the BRI is that the former falls within a single political jurisdiction where the geo-political intent is clearly specified (i.e., EU and its Eastern Partnership member states). Whereas the promoters of BRI (ultimately the Chinese Government) need to address far more complex and heterogeneous political realities by focussing on mutually beneficial economic outcomes across several continents. Another notable distinction is that the EU has developed and applied common guidelines since 1996, setting out objectives and priorities of common interest for all TENS-T projects, subsequently encapsulating these in action plans.

Figure 4. The belt and road initiative.

Source: Merics (Citation2018)

Reflecting on a point raised earlier, regarding the growing reliance on private sector investment, we also contend that in these evolving contexts of neoliberalism, the changing dynamics of globalisation and climate change, privatisation has been increasingly instrumental in redefining infrastructure needs in places and spaces that suit global markets rather than communities and local economies (Dimitriou Citation2005; Citation2009; Sol Citation2019) and that this also applies to the TENs programme. These concerns are especially reflected in the extensive push to introduce public private partnerships (PPPs) globally for the delivery of mega infrastructure projects, especially in the transport sector. Once relatively rare and limited to a handful of countries and infrastructure sectors, PPPs have emerged world-wide as a key procurement modality that governments seek to use to address their infrastructure deficits. Despite widespread narratives about their supposed success, opinion about the efficacy of PPPs is divided, with support for their deployment compromised by increasing political debate about ownership rather than factual analysis of actual outcomes (Helby Petersen Citation2019). In retrospect, there clearly needs to be a more robust evidence base of good PPP practice, with much greater emphasis on differentiation in development contexts and institutional and governance capacities, to ensure the approach can be exploited more securely (Hodge and Greve Citation2019).

Notwithstanding, the scale of finance required to address infrastructure investment shortfalls, however modest the forecasts, highlights the critical role that the private sector should/will/must play if investment deficits are to be addressed (Yescombe and Farquharson Citation2018). How this should be done, however, remains open to debate. Against this backdrop, we argue that it is not the notion of PPPs that is flawed. How can one challenge the need for partnership in public and private financing of major infrastructure projects when there is such shortage of funding and expertise in the public sector? What instead is required is a redressing of the balance of emphasis, by seeking to match the current focus on private sector interests, more reflective of the UK’s early private finance initiatives (PFIs) (Edwards Citation2004), with a better understanding of the needs, priorities and capacities of the public sector, and then to jointly develop more balanced and sustainable partnerships of mutual benefit to both parties.Footnote13