ABSTRACT

Hyperarousal and attention problems as a result of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are being recognized as a risk for offense recidivism. Short-term Music therapy Attention and Arousal Regulation Treatment (SMAART) was designed as a first step intervention to address responsivity and treatment needs of prisoners who were not eligible for or unwilling to undergo eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy. This article describes a pilot study of the manualized SMAART protocol in a Penitentiary Psychiatric Center (PPC) and whether there is an increase of focused and sustained attention and a decline of arousal symptoms in prisoners suffering from PTSD, attributable to SMAART. A single case baseline-treatment-design with pre- and post-assessment (N = 13) was used. PTSD prevalence and severity were assessed using the Primary Care-PTSD screen and the PTSD Symptom Scale Interview. Selective and sustained attention was assessed using the Bourdon–Wiersma dot cancellation test. The results show a promising decline of arousal symptoms as well as improved selective and sustained attention levels in the subjects. Also, after the SMAART intervention, five participants no longer met the threshold for a PTSD diagnosis. The results show that the SMAART protocol could be implemented in the PPC-setting. Although the clinical results of the manualized SMAART protocol suggest improvement, this is a small feasibility study so the results must be interpreted with care. Suggestions for future research are offered.

Introduction

Research suggests that there is a substantial but largely ignored prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in prison settings ranging from six percent to as much as 32 percent (Baranyi, Cassidy, Fazel, Priebe, & Mundt, Citation2018; Pettus-Davis, Renn, & Motley, Citation2016). Over the past years, the possible link between PTSD and re-offending has gained more attention (Sommer et al., Citation2017; Wahlstrom, Scott, Tuliao, DiLillo, & McChargue, Citation2015). Barret, Teesson, and Mills (Citation2014) as well as Sadeh and McNiel (Citation2015) found that the PTSD hyperarousal symptoms were significantly correlated with increased recidivism risk. Despite the growing knowledge of the detrimental effects of PTSD on prisoners, research into effective treatment options within a prison setting is scarce (Pettus-Davis et al., Citation2016; Yoon, Slade, & Fazel, Citation2017). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy is considered a first choice treatment for PTSD, but not all prisoners suffering from this disorder are eligible for EMDR due to language and motivation issues, difficulties with emotion regulation, severe acting out behavior as well as the prison setting, which can be perceived as unsafe and stressful (Miller & Najavits, Citation2012). A Short-term Music therapy Attention and Arousal Regulation Treatment (SMAART) was developed as a means to address hyperarousal and improve responsivity to treatment.

Music therapy in forensic care

“Music therapy is the clinical and evidence-based use of music interventions to accomplish individualized goals within a therapeutic relationship by a credentialed professional” (American Music Therapy Association). It has a long history in forensic psychiatric care and correctional settings (Chen, Hannibal, Xu, & Gold, Citation2014) starting as early as the beginning of the twentieth century when Van de Wall (Citation1924) published his text on the use of music for the treatment of prisoners. One of the great advantages of music therapy in forensic psychiatric care is that it can be tailored to match the responsivity level of the patients aligning with their motivation and level of functioning (Hakvoort & Bogaerts, Citation2013). Forensic music therapy is directed at reducing offense related recidivism either by targeting specific risk factors (Compton-Dickinson & Hakvoort, Citation2017; Hakvoort & Bogaerts, Citation2013) and/or by enhancing protective factors (Chen et al., Citation2014). In SMAART the focus on attention and arousal regulation speaks to enhancing protective factors, which in turn affect the risk factor of hyperarousal that is correlated with a heightened recidivism risk (Sadeh & McNiel, Citation2015). With PTSD symptoms posing a heightened risk of offense related recidivism, treating prisoners with PTSD with music therapy may be an expedient choice. The challenge for the music therapist in the PPC is the relatively short stay of the prisoners, as this limits treatment options when compared to other forensic psychiatric treatment programs. Based on the average amount of seven treatment sessions in the PPC, a choice was made to design a manualized intervention for six sessions with homework assignments. The following paragraphs will briefly describe the theoretical background of SMAART before detailing the current study parameters.

Theoretical background of SMAART

SMAART is built on information drawn from the neurobiology of trauma, neurobiology of music, music therapy in forensic care, and neurologic music therapy. The therapeutic techniques used in SMAART focus on calming the stress response in the brain by incorporating abdominal breathing techniques, rhythmical entrainment, bilateral movement patterns in music with body percussion, and musical attention control training. Neuroimaging studies have exposed neural irregularities in the lower brain regions in persons with PTSD (Bremner, Citation2007). These irregularities make it practically impossible for the brain to move beyond the instinctual trauma responses to engage the executive functions; severely limiting self-regulation (Perry, Citation2009; Tinnin & Gantt, Citation2013; Van der Kolk, Citation2014). In an interview with MacKinnon, Perry discusses the need for “patterned, repetitive, rhythmic, somatosensory input” (including music) as a means to increase self-regulation in the lower areas of the brain (MacKinnon, Citation2012, p. 214). Providing the brain with “patterned repetitive rhythmic (…) input” (MacKinnon, Citation2012) to address irregularities in the lower brain area, suggests that music therapy might be the treatment of choice. In SMAART body-percussion rhythms are used as a means to incorporate a somatosensory element, while involving both sides of the brain at the same time to assist in keeping the focus of the patient in the present and promoting interhemispheric integration (Tinnin & Gantt, Citation2013). Since repetition is key to regulating and retraining the brain, this was included as an important component of the SMAART music therapy intervention. A strength of music therapy lies in the biological effects that music has on the brain. Research has shown how the brain responds to rhythm with synchronization, entrainment, stimulation of the reward system and a calming of the amygdala (Braun Janzen & Thaut, Citation2018). Peretz and Zatorre (Citation2003) found that music enters the brain via the brainstem where it affects pulsing. Music therefore fits with the earlier mentioned bottom-up development of the brain and can provide access even when the higher functioning levels of the brain are less active due to stress reactions in the brain. In SMAART the therapist works with repetitive patterns and rhythms guided by a metronome to ensure rhythmical entrainment.

Patients suffering from PTSD frequently experience attention problems (Quereshi et al., Citation2011). Their attention is often disturbed by intrusive memories, as well as heightened awareness and arousal, causing them to constantly scan their environment for possible danger, thus enforcing a divided attention mode (Van der Kolk, Citation2014). Attention has been described as a fundamental cognitive skill that enables us to develop other skills and supports our daily functioning (Posner, Citation2012; Rosario Ruedo, Pozuelos, & Cómbita, Citation2015). In forensic psychiatric care this could be one of the phenomena that might contribute to poor treatment adherence as it disrupts the prisoner’s ability to absorb new information and implement new behavioral strategies (Cornet, Van der Laan, Nijman, Tollenaar, & De Kogel, Citation2015). Therefore, one of the therapeutic techniques used in SMAART centers around the first steps of the musical attention control training (MACT, Thaut & Gardiner, Citation2014), a technique from the neurologic music therapy (Thaut & Hoemberg, Citation2014), which focuses on improving sustained and selective attention. The MACT steps applied in SMAART make use of the innate qualities of music to activate attentional networks through the auditory sensory pathways in the brain. “Music brings timing, grouping, and organization, so that attention can be sustained.” (Thaut & Gardiner, Citation2014, p. 260). In SMAART this is done using body percussion rhythms, rhythmical playing on the xylophone, and African drums. The first step targets sustained attention by keeping to a rhythmic pattern. The second step is to train selective attention. The prisoner must maintain hisFootnote1 rhythmic pattern while the music therapist provides a competing musical stimulus. Improving the attentional skills could help to retrain the prisoner’s brain to stay focused in the present when interrupted by intrusive memories and recurring fears.

To assess the viability of this new music therapy intervention for adult male prisoners with PTSD, a feasibility study was designed. The following research questions were formulated:

Can a short-term music therapy intervention of 6 individual sessions of maximally 60 minutes (SMAART, Macfarlane, Citation2014) have a clinically relevant positive influence on sustained and selective attention for prisoners with PTSD?

Can SMAART decrease the level(s) of arousal with a clinically relevant percentage, measured by decreasing the number of trauma symptoms?

Method

Setting

This study took place in the PPC of the Dutch Penitentiary Vught (PI Vught). Treatment in the PPC is a two-pronged approach offering psychiatric care to help manage the incapacitating effects of psychiatric disorders as well as tailoring the various treatment interventions to address potential recidivism risks based on the risk-need-responsivity (RNR) model of Bonta and Andrews (Citation2007). The average length of stay of prisoners in the PPC is three to five months. The prisoners placed in the PPC are at different stages of their judicial path with more than half of them awaiting trial and sentencing. Their release from the PPC is mainly determined by the advancement of their judicial path and not based on treatment progress.

Research design

As SMAART is a new music therapy intervention, a simple pre-posttest single case experimental design was chosen as the best fit for the complexities of the setting and the clinical population. This pilot study was approved by the scientific department of the Dutch Ministry of Justice and Security with respect to procedural and ethical aspects. Written informed consent was obtained from each prisoner who met the minimum cutoff score for PTSD on the PTSD symptom Scale Interview version (Foa & Tolin, Citation2000) after having received oral and written information about the study. Pre- and posttest measurements were conducted by a qualified psychologist (see measures for instruments that were used). Study participation was voluntary; prisoners who refused to participate in the study still could receive SMAART or music therapy treatment but were excluded from the study. To monitor the progress on the PTSD hyperarousal subscale, the PSS-I (Foa & Tolin, Citation2000) was administered on a weekly basis, starting at intake during the entire intervention period. In addition, spontaneous feedback given by participants was noted by the music therapist (see ).

Participants

Based on the formulated inclusion criteria, a convenience sampling method was applied. The inclusion criteria were minimal: to be included as a participant, the prisoner had to meet the diagnostic cut off score for PTSD, had not to be in a florid psychotic state, and had not to have unpredictable aggressive outbursts. Sixteen participants were recruited. Of these original sixteen participants three discontinued the study for various reasons. One because he was transferred to another prison facility during the intervention period. The second stopped due to the stress elicited by the PSS-I interview. The third was taken out of the study for safety reasons for the music therapist. Participants in this study were all adult male prisoners placed in a PPC who had been diagnosed with PTSD, who were either not eligible or unwilling to undergo EMDR or any other specific PTSD-treatment.

In this study, PTSD was diagnosed using DSM-IV-R (APA, Citation2000) criteria, which contains three subcategories: intrusive memories, avoidance and hyperarousal (the study took place in 2015, when the DSM-5 was not yet in use in PPC Vught). All of the participants met the criteria for full PTSD. None were diagnosed with a dissociative subtype of PTSD. No distinction was made between types of trauma or number of traumatic events (see ).

Table 1. Types of trauma.

Most of the participants had multiple traumatic experiences and the majority (N = 9) had not sought help for their symptoms before participation in this study. Prisoners frequently complained of their wandering attention leading to difficulties in absorbing new information, inability to read, follow a prolonged conversation, watch TV and maintain contact with significant others and family members (information provided by prisoners during diagnostic interviews in the PPC).

Measures

As mentioned all pre-and posttest measures were conducted by a trained psychologist. In order to monitor the hyperarousal symptoms during the course of the intervention, the music therapist administered the PSSI weekly at the start of the music therapy session.

Primary care PTSD (PC-PTSD)

A Dutch version of the PC-PTSD was used for preliminary assessment of PTSD when prisoners entered the PPC. Prins et al. (Citation2003) developed the screener for primary care settings. The PC-PTSD was specifically designed by Prins et al. (Citation2003) to be comprehensible to everybody functioning at an eighth-grade (and above) reading level. Given the high rates (30–45%) of intellectual disability (Kaal, Citation2016) as well as the diverse backgrounds and different levels of comorbidity of the prison population, the PC-PTSD was chosen as the best fit for the prison population. For this study the cutoff score of 3 was used as suggested by Prins et al. (Citation2003) taking into account that arousal levels could be elevated due to incarceration.

PTSD symptom scale interview (PSS-I)

The Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS; Blake et al., Citation1995) is considered the most reliable diagnostic tool for PTSD (Kristiansson, Sumelius, & Søndergaard, Citation2004). However, a problem with the CAPS is the long assessment time. A long assessment time is unfavorable for the PPC population and a choice was made to use the less time-consuming PTSD Symptom Scale Interview (PSSI, Foa & Tolin, Citation2000). It is a 17-item instrument to assess PTSD and PTSD severity is determined by totaling the 17 item ratings. The scoring ranges from 0 to 51. The cutoff score of the PSS-I is 15. In this study, the Dutch version of the PSS-I (Engelhard, Arntz, & van den Hout, Citation2007) was applied. Powers, Gillihan, Rosenfield, Jerud, and Foa (Citation2012) researched the reliability and validity of the PSS-I among participants with PTSD and alcohol dependence. A sensitivity of .95 and a specificity of .70 were found. They concluded that the PSS-I performed well and can be used to assess PTSD diagnosis (Powers et al., Citation2012).

Bourdon-Wiersma dot cancellation test

The Bourdon-Wiersma (Bourdon et al., Citation1977) dot cancellation test targets selective and sustained attention. The BW consists of 50 lines with groups of three, four and five dots. The groups with four dots (in different constellations) are defined as targets and the groups of three and five dots are considered distractors. Participants are required to mark all the target groups of four dots as quickly and as accurately as possible (Van Zomeren & Brouwer, Citation1992). Spikman and Van Zomeren (Citation2010) describe the BW test as a “tactical level” (p. 84) test, meaning that it is partially structured with a little added time pressure (subjects are instructed to work as fast as possible) and memory driven (rules and instructions must be kept active in the working memory in order to complete the task). Ignoring the distracting stimuli (the groups of three and five dots) targets selective attention while attending to the 50 lines of dot groups is directed at maintaining sustained attention.

In this study the duration of the completion of the BW was calculated as well as the number of “mistakes” and “misses”. “Mistakes” are when the participant crosses off the wrong cluster of dots. “Misses” are the correct dot clusters that the participant failed to cancel out. The reason to use it instead of, for instance, the D2-CP test, was because it doesn’t require letter recognition, thereby taking into account that some of the participants were not always familiar with the European alphabet or had literacy problems.

Intervention

SMAART provides a protocolled intervention focusing on the first steps of trauma treatment (decreasing hyperarousal, while also improving sustained and selective attention skills) through musical (rhythmic and breathing) assignments. As mentioned, every step of SMAART is geared toward the application of musical assignments to calm the brain’s stress response and cue attention. Due to the heterogeneity of the PPC population regarding mental status, offense type, and primary language, and due to the relatively short stay of prisoners in the PPC, SMAART was developed and carried out as an individual treatment intervention.

Adhering to the APA (Citation2017) guidelines for trauma-treatment, SMAART starts with concise psycho-education on common reactions to traumatic events and the brain and stress. This explanation is basic and helps the participant to understand the focal point of the exercises: calming the brain. The psycho-education is followed by low and slow breathing exercises that are directed at increasing awareness of the participant’s breathing pattern when tension is high and how to use breathing to regulate this. Singing can be part of this step as a means to regulate breathing. During the first session the therapist asks the participant to concentrate on his breathing. If he is unable to do this, the participant is asked to sing simple songs and imitate the music therapist’s example of abdominal breathing.

SMAART continues with the focus on decreasing hyperarousal and being alert in the present using rhythmic exercises starting with both hands beating a pulse on the thighs at a speed of 40 to 60 beats per minute (bpm) as guided by the use of a metronome. Once the participant can keep a pulse going with the metronome, he is urged to start subdividing the pattern in two with the dominant hand while maintaining the pulse with both hands and the metronome (see ).

The MACT steps focusing on sustained and selective attention are then introduced in varying musical combinations. Throughout the intervention the musical tasks are used as opportunities for the prisoner to implement the learned calming techniques and strategies. Each increment of speed and or additional rhythmic pattern provides moments for the participant to experience rising tension and learn to regulate his breathing as well as maintaining his focus in the present. For this purpose, the music therapist provides live feedback on bodily signs of rising stress/tension as witnessed in the participant. The therapist guides the prisoner in the application of slow breathing and regaining their focus. This is directed toward enhancing the participant’s sense of mastery in dealing with arousal symptoms. Participants were given the body percussion and breathing exercises as daily homework between the music therapy sessions along with a daily log to keep track of how often they performed the exercises. For a detailed description of SMAART see Macfarlane (Citationin press).

Participants received treatment as usual (TAU) and were offered the short-term music therapy treatment. Treatment as usual consisted of the daily prison program with sports, library, work, church and other activities with fellow prisoners. No other types of musical or art-based therapies were offered in the daily program. Also, as part of TAU, the participants received weekly meetings with their mentor, their treatment coordinator, and a psychiatrist who monitored their psychotropic medication. At the time of their participation in the study, the participants were not receiving any type of psychological treatment either due to their own refusal, language barriers or low treatment responsiveness.

Results

Demographics of the prisoners who participated in the SMAART intervention. (see for characteristics).

Table 2. Characteristics of the participants.

The participants had very diverse backgrounds, comorbidity and nationalities. They were also at different stages in their judicial path. Some participants were “first offenders” while others had been in prison before. Their backgrounds varied from (illegal) immigrants (N = 2), to veterans (N = 2). They were men who had been sexually and/or physically assaulted or who had suffered from other traumatic situations (N = 9). Around 45% (N = 6) of the participants had a substance use disorder but were not using drugs at the time of the studyFootnote2. Other comorbid diagnoses were mixed: cluster B personality -to autism spectrum -to intellectually challenged, depression and psychotic disorders, thus representing a cross section of a “typical” prison population within the PPC. Index offenses ranged from interpersonal violence (N = 8), violent crime (N = 4) to major fraud (N = 1). All participants but one were on psychotropic medication.

Attendance to all six SMAART sessions was 100%

Adherence to the homework assignments differed substantially among the participants as could be seen in the daily logs which were brought to each session by the participants. The prisoners who made the most progress were also the ones who had adhered to the daily routine of the homework assignments.

Attention

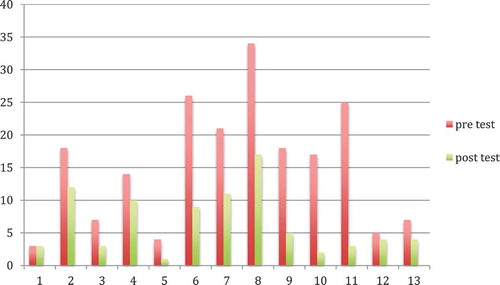

Changes in attention scores were obtained by comparing the BW scores from the pre- with the post-test (see ).

Figure 3. Results of dot cancellation test (“misses”).

Y-axis is the amount of “misses”, X-axis is each participant.

There was no difference in the number of “mistakes” pre- and posttest (average mistakes = 5) but there were differences in the scores for “misses”. The individual response charts showed that there was still quite a bit of fluctuation in the participants’ attention. However, for all but one of the participants their amount of “misses” decreased. The total amount of “misses” in the pre-test was 185. For the post-test this was 84, which meant an average improvement of 54.5%. This can be interpreted as improved sustained and selective attention.

Hyper-arousal and PTSD symptoms

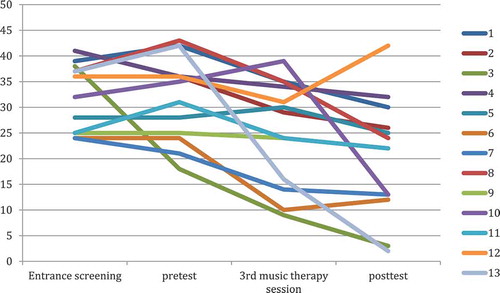

demonstrates the changes of the PSS-I score for each individual participant as measured at Screening (entrance), Intake, Middle and Final assessments.

Figure 4. Course of PTSD symptoms during music therapy intervention.

The Y-axis depicts the PSSI score, the X-axis represents the moments of measurement.

shows that there is an average reduction of PTSD symptoms of 38% between the entrance screening and the final point of the intervention. Individual effect sizes can be seen in the last column of . A drop of ten points or more is considered clinically relevant (Monson et al., Citation2008). This was the case for eight of the participants of which five had a final score below PTSD threshold.

Table 3. PTSD symptoms as scored on the PSSI-5#, before, during and after music therapy intervention.

Individual results

As can be seen in there is one participant (number 12) who seemed to improve but then finished with a higher score than he started with. The increase of symptoms started after he had received positive feedback from the multidisciplinary team on the progress he was making. Despite the higher symptom level, he did insist that he felt more empowered to deal with symptoms by applying the breathing and arousal reduction techniques he had mastered during the SMAART intervention. Another interesting line is the third participant whose symptoms can be seen to decline right after the entrance screening. The explanation given by this participant was that he was so relieved that his traumatic experiences were taken seriously, that he immediately felt hopeful and motivated to engage in the treatment and adhered to the daily homework assignments.

Participant’s feedback

Participants reported various effects of the music therapy interventions. Some (N = 5) reported changes in the content of their nightmares (less scary), while seven reported that nightmares had stopped altogether. Some were able to read and retain information better, which allowed them to start education (again). In addition, participants reported feeling a greater sense of empowerment because they were able to manage their arousal, could keep their attention focused in the here and now, felt safer and no longer dependent on help from others to calm themselves. A turning point for all was the moment that they made the distinction between trauma related arousal, avoidance behavior and responses associated with daily life. Most (N = 12) were surprised by the effect of the intervention and satisfied with the outcome.

Discussion

This is the first report of a music therapy intervention targeting attention and diminishing arousal in an adult male penitentiary psychiatric population diagnosed with PTSD. In a pilot study in a forensic psychiatric hospital Van Alphen, Stams, and Hakvoort (Citation2019) found that MACT had a positive effect on attention skills, but that study was not directed at targeting PTSD hyperarousal symptoms. There are no other reports on short-term music therapy for adult male prisoners with PTSD. This study was directed at testing the application of a time-limited and manualized music therapy intervention (SMAART) within a challenging clinical context. The decision to target sustained and selective attention proved to be fruitful. Not only did the prisoners demonstrate improved sustained and selective attention, the short-term music therapy intervention of 6 individual sessions also lowered levels of arousal as found by the decrease in the number of trauma symptoms. The direct benefits of the reduction of PTSD symptoms were reported by most of the prisoners by the end of the intervention.

The following limitations of this study need to be taken into account when interpreting the results. The sample size is small and with a voluntary bias due to ethical considerations relating to the population, there was no randomization and not all participants adhered to the dosage of the homework assignments thereby minimizing the high number of repetitions that were deemed necessary. At this moment a possible Hawthorne effect can’t be ruled out, an effect that refers to (temporary) positive productivity as a result of receiving attention from researchers (Landsberger, Citation1958). We discussed two potential occurrences of this effect (participant 12 and 3). However, it is expected that this effect was minimal due to the fact that participant 12 even scored higher on the PTSD measure at posttest, despite stating that he was feeling more in control of his arousal symptoms. In addition, participants were already receiving attention from various professionals during their stay in the PPC. Furthermore, the short stay in the PPC had an adverse effect on the two-month follow-up data collection point that was planned, because most participants had left by that time. Due to ethical restraints it was not possible to contact prisoners once they were no longer in the PPC. In their systematic review and meta-analysis Yoon et al. (Citation2017) report that post treatment follow-up and institutional constraints are the most commonly encountered difficulties when conducting research in a prison setting. These difficulties were also present with this study and can be seen in the lack of follow-up data.

An independent, accredited psychologist did the entrance screening. The pre-and posttests were carried out by the same psychologist who was therefore not blinded to the outcome of the pretest. All the other screenings (weekly monitoring) were completed by the music therapist that administered the intervention and is the first author of this article (see assessment flowchart ). This might have triggered different levels of bias (performance, attrition and reporting) but it is considered good clinical practice for a therapist to monitor a patient’s progress.

Despite these limitations, this pilot study suggests that SMAART could improve sustained and selective attention and decrease PTSD-symptoms of prisoners suffering from PTSD. In a replication study of SMAART in an addiction treatment center, with participants with PTSD and Substance Use Disorder similar results were found (Hakvoort et al., in review).

Recommendations

These preliminary study results suggest clinically relevant positive changes. Since there are no control-participants, nor any randomization, nor blinding in the majority of the assessment, this study could be biased. Therefore, future research should try to eliminate the largest shortcomings. This study should be replicated in a randomized design with independent music therapists in multiple centers like PPCs and other forensic psychiatric settings. Due to the nature of music therapy treatment, a double-blind design will be difficult to achieve. However, a single blind design for the researcher would be attainable. It is also recommended to use a mixed method approach so that data collected from spontaneous feedback can be analyzed systematically. Future questions might address the optimum time frame in which to deliver SMAART and how it might be an “entry intervention” that could prime prisoners with complex trauma and complex PTSD for further trauma-focused treatment. Additional exploration of the possible moderating effect of comorbidity might reveal more specific in- or exclusion criteria. Finally, it would be interesting to assess a way to help stimulate a high dosage of the homework exercises in between the therapy sessions, as according to the literature, and as seen in the results of those who adhered to the daily homework assignments, repetition is a key success factor.

Conclusion

SMAART is the first manualized and time-limited music therapy treatment for PTSD focusing on the first step of calming the stress response in the brain. Directly addressing the prisoners’ needs for improvement of their ability to focus and sustain attention and increase mastery over arousal symptoms helped to keep them engaged in the treatment. The unique qualities of music that matched the biological language of the brain, but also appealed to prisoners’ responsivity (as one prisoner put it: “music is the only other good thing in life”) made SMAART relatively easy to implement and have a low dropout rate, proving it an interesting option for settings seeking to enhance treatment adherence. The strength of this practice-driven research experiment is that it has shown that it is applicable in a complex clinical setting with a very mixed and treatment resistant population, who were (for whatever reason) not eligible for EMDR or another type of trauma treatment, at the moment of enrollment.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 PI Vught is an all-male prison facility.

2 Drug abuse in the PPC is monitored via regular urine testing. There is a strict no-use policy and most prisoners try to adhere to this because of the punitive measures that can be imposed in case of proven drug use.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2000). The diagnostic and statistical manual (4th ed., —text revision). Washington, DC: Author.

- American Psychological Association. (2017). Clinical practice guideline for the treatment of PTSD. Washington, DC.

- Baranyi, G., Cassidy, M., Fazel, S., Priebe, S., & Mundt, A. (2018). Prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder in prisoners. Epidemiologic Reviews, 40, 134–145. doi:10.1093/epirev/mxx015

- Barret, E. L., Teesson, M., & Mills, K. L. (2014). Associations between substance use, post-traumatic stress disorder and the perpetration of violence: A longitudinal investigation. Addictive Behaviors, 39(2014), 1075–1080. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.03.003

- Blake, D. D., Weathers, F. W., Nagy, L. M., Kaloupek, D. G., Gusman, F. D., Charney, D. S., & Keane, T. M. (1995). The development of a clinician-administered PTSD scale. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 8(1), 75–90.

- Bonta, J., & Andrews, D. A. (2007). Risk-need-responsitivity model for offender assessment and rehabilitation. Canada: Public Safety Canada.

- Bourdon, B., Wiersma, E. D., van der Ven, A. H. G. S., Hofhuizen, J. W. M., Weis, C., Hofhuizen-Hagemeyer, J. W. M., & Mesker, P. (1977). Bourdon-Wiersma test. Instituut voor Clinische en Industriële Psychologie (ICIP), Utrecht.

- Braun Janzen, T., & Thaut, M. H. (2018). Cerebral organization of music processing. In M. H. Thaut & D. A. Hodges (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of music and neuroscience (pp. 1–41). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bremner, J. D. (2007). Neurobiology of posttraumatic stress disorder. In G. Fink (Ed.), Encyclopedia of stress (2nd ed., pp. 152–157). New York: Academic Press.

- Chen, X. J., Hannibal, N., Xu, K., & Gold, C. (2014). Group music therapy for prisoners: A protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Nordic Journal of Music Therapy, 23(3), 224–241. doi:10.1080/08098131.2013.854268

- Compton-Dickinson, S., & Hakvoort, L. (2017). The clinician’s guide to forensic music therapy. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Cornet, L. J. M., Van der Laan, P. H., Nijman, H. L. I., Tollenaar, N., & De Kogel, C. H. (2015). Neurobiological factors as predictors of prisoners’ response to a cognitive skills training. Journal of Criminal Justice, 43(2), 122–132. doi:10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2015.02.003

- Engelhard, I. M., Arntz, A., & van den Hout, M. A. (2007). Low specificity of symptoms on the post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptom scale: A comparison of individuals with PTSD, individuals with other anxiety disorders and individuals without psychopathology. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 46, 449–456. doi:10.1348/014466507X206883

- Foa, E. B., & Tolin, D. F. (2000). Comparison of the PTSD symptom scale-interview version and the clinician-administered PTSD scale. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 13, 181–191. doi:10.1023/A:1007781909213

- Hakvoort, L., & Bogaerts, S. (2013). Theoretical foundations and workable assumptions for cognitive behavioral music therapy in forensic psychiatry. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 40, 192–200. doi:10.1016/j.aip.2013.01.001

- Hakvoort, L., De Jong, S., Van der Ree, M., Kok, T., Macfarlane, C., & De Haan, H. (in review). A short-term music therapy for patients with substance use- and posttraumatic stress disorders: A pilot study for hyperarousal and attention.

- Kaal, H. (2016). Prevalentie Licht Verstandelijke Beperking in het Justitiedomein. Notitie in opdracht van het Ministerie van Veiligheid en Justitie, Leiden.

- Kristiansson, M., Sumelius, K., & Søndergaard, H. (2004). Post-traumatic stress disorder in the forensic psychiatric setting. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 32, 399–407.

- Landsberger, H. A. (1958). Hawthorne revisited. New York, Ithaca: The New York State School of Industrial and Labor Relations.

- Macfarlane, C. (2014, July). Treating trauma behind bars. Presentation 14th world congress music therapy. Krems, Austria.

- Macfarlane, C. (in press). Development of the SMAART protocol for adult male prisoners with PTSD. Music Therapy Today, special edition on music therapy and trauma treatment.

- MacKinnon, L. (2012). Neurosequential model of therapeutics: Interview with bruce perry. The Australian & New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy, 33(3), 210–218. doi:10.1017/aft.2012.26

- Miller, N. A., & Najavits, L. M. (2012). Creating trauma-informed correctional care: A balance of goals and environment. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 3, 1–8. doi:10.3402/ejpt.v3i0.17246

- Monson, C. M., Gradus, J. L., Young-Xu, Y., Schnurr, P. P., Price, J. L., & Schumm, J. A. (2008). Change in posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms: Do clinicians and patients agree? Psychological Assessment, 20, 131–138. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.20.2.131

- Peretz, I., & Zatorre, R. J. (Eds.). (2003). The cognitive neuroscience of music. New York: Oxford Press.

- Perry, B. (2009). Examining child maltreatment through a neurodevelopmental lens: Clinical applications of the neurosequential model of therapeutics. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 14, 240–255. doi:10.1080/15325020903004350

- Pettus-Davis, C., Renn, T., & Motley, R. (2016). Conceptual model to guide practice and research in the development of trauma interventions for men releasing from incarceration. St. Louis: Institute for Advancing Justice Research and Innovation.

- Posner, M. I. (ed.). (2012). Cognitive neuroscience of attention (2nd ed.). New York: Guildford Press.

- Powers, M. B., Gillihan, S. J., Rosenfield, D., Jerud, A. B., & Foa, E. B. (2012). Reliability and validity of the PDS and PSS-I among participants with PTSD and alcohol dependence. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 26, 617–623. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2012.02.013

- Prins, A., Ouimette, P., Kimerling, R., Cameron, R. P., Hugelshofer, D. S., Shaw-Hegwer, J., … Sheikh, J. I. (2003). The primary care PTSD screen (PC-PTSD): Development and operating characteristics. Primary Care Psychiatry, 9, 9–14. doi:10.1185/135525703125002360

- Quereshi, S. U., Long, M. E., Bradshaw, M. R., Pyne, J. M., Magruder, K. M., Kimbrell, T., … Kunik, M. E. (2011). Does PTSD impair cognition beyond the effect of trauma? Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 23(1), 16–28. doi:10.1176/jnp.23.1.jnp16

- Rosario Ruedo, M., Pozuelos, J. P., & Cómbita, L. M. (2015). Cognitive neuroscience of attention. AIMS Neuroscience, 2(4), 183–202. doi:10.3934/Neuroscience.4.183

- Sadeh, & McNiel. (2015, June). PTSD increases risk of criminal recidivism among justice-involved persons with mental disorder. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 42(6), 573–586. doi:10.1177/0093854814556880

- Sommer, J., Hinsberger, M., Elbert, T., Holtzhausen, L., Kaminer, D., Seedat, S., … Weierstall, R. (2017). The interplay between trauma, substance abuse and appetitive aggression and its relation to criminal activity among high-risk males in South Africa. Addictive Behavior, 64, 29–34. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.08.008

- Spikman, J., & Van Zomeren, A. H. (2010). Assessment of attention. In J. Gurd, U. Klischka, & J. Marshall (Eds.), The handbook of clinical neuropsychology (2nd ed., pp. 81–96). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Thaut, M. H., & Gardiner, J. C. (2014). Music attention control training. In M. H. Thaut & V. Hoemberg (Eds.), Handbook of neurologic music therapy (pp. 257–269). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Thaut, M. H., & Hoemberg, V. (2014). Handbook of neurologic music therapy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Tinnin, L., & Gantt, L. (2013). The instinctual trauma response dual-brain dynamics. A guide for trauma therapy. Morgantown, West Virginia: Gargoyle Press.

- Van Alphen, R., Stams, G. J. J. M., & Hakvoort, L. (2019). Musical attention control training for psychotic patients: An experimental pilot study in a forensic psychiatric hospital. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 13, 570. doi:10.3389/fnins.2019.00570

- Van de Wall, W. (1924). The utilization of music in prisons and mental hospitals, its application in the treatment and care of the morally and mentally afflicted. New York: Published for the Committee for the Study of Music in Institutions by the National Bureau for the Advancement of Music.

- Van der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. New York: Penguin Group.

- Van Zomeren, A. H., & Brouwer, W. H. (1992). Assessment of Attention. In J. R. Crawford, D. M. Parker, & W. W. McKinlay (Eds.), A handbook of Neuropsychological Assessment (pp. 241–266). Hove, UK: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- Wahlstrom, L. C., Scott, J. P., Tuliao, A. P., DiLillo, D., & McChargue, D. E. (2015). Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, emotion dysregulation, and aggressive behavior among incarcerated methamphetamine users. Journal of Dual Diagnosis, 11(2), 118–127. doi:10.1080/15504263.2015.1025026

- Yoon, I., Slade, K., & Fazel, S. (2017). Outcomes of psychological therapies for prisoners with mental health problems: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 85(8), 783–802. doi:10.1037/ccp0000214