ABSTRACT

Several previous studies have shown an overrepresentation of reading and writing difficulties among patients in psychiatric clinics. However, few studies have conducted reading interventions aimed at improving patients’ reading ability. The present study aimed to investigate the sustainability of a previously implemented reading intervention one year after completion. Furthermore, the purpose was to examine how patients perceived a reading intervention and how they experienced their previous schooling. Participants comprised 20 patients who had previously undergone 13 sessions of reading interventions. The results showed that the patients had maintained the same reading level they had immediately after the interventions ended. Most participants had experienced troublesome schooling. However, they perceived reading interventions as a rewarding and meaningful activity at the institutions. The results are discussed concerning social, pedagogical, and psychological aspects.

An abundance of research has shown that there is a substantial overrepresentation of individuals with difficulties in the written language among prisoners, juvenile delinquents in correctional institutions, and among patients within forensic psychiatric settings (Svensson, Citation2011). Earlier studies have reported a prevalence of 30–70% of difficulties with the written language, including dyslexia, among these subgroups (Grigorenko, Citation2006). The relatively huge, reported differences in the prevalence of reading and writing disabilities and dyslexia mostly depend on the applied cutoff or criteria (Svensson, Citation2011). In a study by Svensson et al. (Citation2015), 63% of the patients in a forensic clinic demonstrated a reading ability below average for grade six, whereas 16% showed dyslexic symptoms; 12% among the Swedes and 28% among the immigrants. The results regarding reading and writing difficulties were consistent with earlier studies (Selenius et al., Citation2006; Selenius & Hellström, Citation2015; Snowling et al., Citation2000) but the prevalence of dyslexia was in the lower bound compared to earlier reported results among persons in correctional institutions.

There is a lack of research on interventions to rehabilitate and adjust the patients into society. Low educational attainment among forensic psychiatric patients is reported as a risk factor for future reconvictions (Krona et al., Citation2017). Furthermore, patients with poor education also have less opportunity to get a job and start studying (Kirsh et al., Citation2019). Problems also arise in institutional care because patients may find it difficult to absorb the necessary information, for example, about the rules that apply at the ward. Patients with significant difficulties with the written language may also find it difficult to follow the spoken language and to express themselves sufficiently nuanced, which may be necessary for various forms of therapeutic interventions. Foreign-born patients seem to be particularly vulnerable within forced institutional care as they encounter demanding oral and written language. Consequently, they are more likely to end up in situations of misunderstandings (Svensson et al., Citation2017). This study aimed to follow up on a reading intervention among forensic patients one year after the intervention.

Earlier research has pinpointed the value of educational interventions for incarcerated to reduce recidivism and to reintegrate into society (Grigorenko, Citation2006; Svensson, Citation2011). The present study followed up a reading intervention among patients with severe reading difficulties in a forensic psychiatric clinic (Svensson et al., Citation2017). Few, if any, investigations have carried out reading interventions among adults admitted to forensic psychiatric care. However, some intervention studies have been conducted among incarcerated youths and adults. For example, in a study by Alvarez et al. (Citation2018), prisoners received a reading intervention including dialogic literary gatherings and reading paragraphs from “universal classic literature” (p. 1044). These texts were then discussed in groups. The prisoners perceived the intervention as helpful for social reintegration. However, the intervention was focused on reading and not on increasing reading skills. Another type of reading intervention among juvenile delinquents was conducted by Warnick and Caldarella (Citation2016). They divided the juvenile delinquents into an experiment and a control group. The experimental group intervention consisted of a multisensory phonics-based reading remediation program, whereas the control group received the standard reading teaching. The delinquents in the experimental group received 37 lessons in 2 months. There was a large effect size for the experimental group on all reading subtests and the total reading score. The authors claimed that multisensory phonics-based reading intervention is useful in developing reading skills among juvenile delinquents. However, the sample size was small and the results require cautious interpretation, according to the authors.

In a recent study by Metsala et al. (Citation2017) the high prevalence of reading disabilities among youths with antisocial behavior was confirmed (Krezmien & Mulcahy, Citation2008; Leone et al., Citation2005; Svensson et al., Citation2001). The youths received an intervention focusing on phonological awareness, decoding, and sound-spelling knowledge. According to the results, positive effects were reported post intervention. The youths gained their reading ability on the same level as the comparison group (without risk for antisocial behavior and with the same intervention). Metsala et al. (Citation2017) concluded that a reading intervention with a focus on decoding skills was effective among youths with antisocial behavior as well as in a wider population. However, to our knowledge, there is no research focusing on the long-term effects of a reading and writing intervention conducting in a correctional setting.

This study bridges this gap by following up a study by Svensson et al. (Citation2017), wherein 44 forensic psychiatric inpatients received 11 hours of reading instruction. All of them had severe reading difficulties (below average for grade five students in compulsory school) and their average age was 31 (SD 9.2). A comparison group of 17 (age 34, SD 8.8) forensic psychiatric patients was also included, who did not receive a literacy intervention or education during the intervention period. The reading intervention was individualized and based on the individual patient’s most obvious reading problem (e.g., decoding, comprehension, or both). The five-week intervention was carried out by three special education teachers in a face-to-face design, at the location for the school activities (for more details about the intervention procedure see Svensson et al., Citation2017).

The results showed that the patients receiving the reading intervention obtained increased scores on reading-related tests such as decoding and reading comprehension, directly after the end of the intervention. Females enhanced their reading ability by almost four grades and were regarded as not having any reading problems after the intervention period. The gains were lesser for males but were still substantial since they increased their reading ability by almost two grades. In the comparison group, there was no increase in reading test scores after the intervention ended (for more details concerning the results see Svensson et al., Citation2017). The results from the study accord with many reading interventions in non-clinical sample studies, i.e. obvious gains in reading ability directly after completion of an intervention (Fälth et al., Citation2013; Torgesen et al., Citation2001). However, in the study by Svensson et al. (Citation2017), there were only 15 sessions over a six-week period (11 hours in total) which is relatively small compared to previous studies (Statens beredning för medicinsk och social utvärdering [Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Service] [SBU], Citation2014). The authors concluded that even a short reading intervention improved the clients reading ability rather substantially and might increase their possibility of a positive transition from a correctional institution into life in society.

However, it is common that the reading ability after an intervention decreases after a while. This mostly depends on students not practicing as intensively and frequently as during the intervention period (see meta-analysis by Suggate, Citation2016). Therefore, it is important to follow up an intervention to investigate its sustainability. To our knowledge, no longitudinal studies regarding reading interventions have been carried out among forensic psychiatric inpatients, previously.

Aim

The main aim of this study was to follow up the reading ability post intervention, among forensic psychiatric patients in the study by Svensson et al. (Citation2017)

Research questions

Have the patients maintained their improved reading ability one year after completing a reading intervention?

How did the participants perceive the reading intervention they carried out?

How did the participants apprehend their earlier schooling?

Method

The present study is a one-year-follow up after a completed reading intervention among 44 patients who were admitted to forensic psychiatric care. The patients received 13 sessions (11 hours in total). The sample in this study belonged to a larger sample of 185 participants (Svensson et al., Citation2017). It took several years to collect data from all 44 participants, but the follow-up data for each forensic psychiatric patient was collected one year after the reading intervention. The present investigation has received ethical approval (Reference number: 96/05) by the Ethics Review Board in Linköping, Sweden (EPN).

Participants

Twenty patients (10 female, 10 male) with an average age of 28.7 (SD = 8.7 years) who had been admitted to forensic psychiatric care, participated in the present follow-up study. The sample was recruited from the 44 patients that received the reading intervention in the study by Svensson et al. (Citation2017). The criteria for participation in the intervention were that patients had severe reading difficulties – average or below grade five for compulsory school pupils. One year after the intervention was finished, with the occasion for the follow-up, some participants were still in care at the forensic clinic (n = 12) and some of them were outpatients or discharged with their own accommodation (n = 8). Among participants with their own accommodations, three participants had completed adult education, two were early retirees, and three had different types of jobs. The attrition rate was 54%. Reasons for the drop out were mainly due to patients refusing to participate in the follow-up: “I’m done with everything that has to do with school.” Some patients did not respond to our request and at least one client was dead (for more detailed information see Svensson et al., Citation2015, Citation2017). However, there were no significant differences between participants and the drop out group according to the reading test at pretest or years in school.

Instruments

The test battery is described in detail in the study by Svensson et al. (Citation2017). However, the present study includes only the reading tests measuring decoding and phonological processing (Wordchains, pseudo-word reading, phonological choice, non-word repetition), orthographic decoding (orthographic choice), and reading comprehension (passage comprehension). Most of the tests have standardized norms, and several researchers have used the tests for many years in the research area of reading and writing disabilities (Lundberg, Citation2010; SBU, Citation2014).

Interview

Furthermore, a short interview (15–20 minutes) at the follow up was carried out by one of the authors with two main questions; “How is your experience of the intervention you carried out?” and “How are your experiences with the previous schooling?”

Procedure

All participants that received the intervention, were asked by the teacher to participate in the follow-up study (approximately one year after each patient had ended the intervention). The tests and the interview were carried out at the institution or in their accommodation, except for two clients who wanted to do the tests and the interview at a library. The interview was conducted in connection with the reading tests at the follow-up. Two open interview questions were discussed, and notes were taken. On average, the total time for the tests and the interview was 1 hour. None of the participants had had any form of reading instruction during the year after the interventions ended.

Results

A paired t-test was used to answer the first research question regarding the sustainability of 11 hours of reading intervention after a one-year follow-up. An effect size (Cohens ´d) was also calculated between pretest and follow-up and posttest and follow-up. Since there were two pretest occasions (T1 and T2) the results were subtracted and divided by two (for more detailed information see Svensson et al., Citation2017). shows raw values regarding mean and standard deviations on all reading tests at baseline, posttest, and at follow-up.

Table 1. Mean and SD for all six tests at three test occasions (pre- post and follow up).

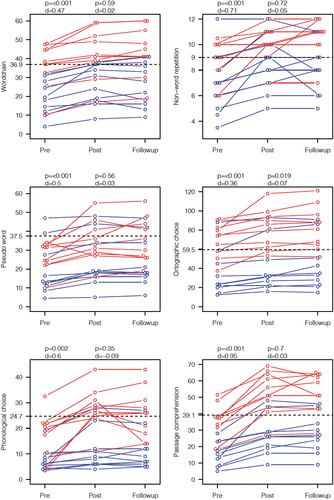

shows a significant difference (p < .01) among all reading-related tests between the pretest and the follow-up test one year later. The effect size varied between moderate to high effect on the tests (range = 0.36–0.95) between pretest and follow-up. In all subtests, females performed better at group level than males at all three measurement occasions. Most females reached above average for grade 6 on the reading test, except for the non-word reading subtest at the follow-up. Males also improved their reading level between pretest and follow-up and retained their ability even one year after interventions were completed. This is particularly evident regarding reading comprehension for both males and females. All females performed above average for grade 6 on the test that measures reading comprehension (passage comprehension) at the follow-up.

Figure 1. Alpha level, Cohens d and grade six level (dotted line) on all six tests for female (red line) and men (blue line) at pre- post and follow up.

Thus, at follow-up the participants received roughly the same result on the test (T4) as in the posttest (T3). It was only on orthographic decoding that they had changed and become significantly better (p < .019). There were no effects except “orthographic choice,” which showed a moderate increase, and ‘phonological choice, which indicated a slight decrease, but not significantly.

Focus of the second research question was to investigate how participants had apprehended the reading intervention they received. This research question as well as the third research question was answered by descriptive comments from participants which emerged in the short interviews. Hereafter, these are presented in running text with quotes from the participants’ statements. The interview was conducted directly after the test procedure at the follow-up and most participants were talkative.

As for the work they did with the interventions, the participants often mentioned the importance of the teacher. They thought it was the teacher’s merit that participants carried out the sessions at all. “I have thought that the teacher is damn important … had the teacher I had here at the ward been at my old school, I probably would not have had so much absence.” Moreover, participants described the school at the clinic as a very good school, where the forensic psychiatric patients had the possibility to get individualized support from a teacher. The participants explained that they could have the teacher by themselves, because of the one-to-one teaching approach. “This is my dream school; no bullies and the teacher say he is here for me.”

According to the interviews, several participants were satisfied that they had managed to complete all intervention sessions and that they had something meaningful to do during the forensic care. For example, one of them stated, “I’ve done ALL the times – so damn what I’ve done well” …. “I figured I could pretend this was my job – I went up two stairs to the job as well – and started with some coffee and a cig I guess that’s how you do it – I would like a job” (the patient had to go from their wards to the location of the school activities).

Some participants mentioned that they had been better at reading and writing or at least dared to do so after the reading intervention. “I have received help to write cards for my child” … “I now dare to write cards for my children and relatives” … “I read the local newspaper and do not just look at the pictures” … “Because I read newspapers, I can talk about other things with my parents and not always about my mood.” “The most fun was today – when I got to see my test results from when we first met at Christmas … [clearly better results at follow-up] and so now … is it really me who fixed it [he smiles with his whole face]?”

The last research question was to understand the participants’ previous schooling. This was done using descriptive data. Hereafter, answers will be presented as descriptive data with quotes from the participants in running texts. Most of the participants reported that their school time, in various ways had been negative. However, some participants thought school was positive, not because of the teaching, but because they had a friend and got food. “So I liked school, at least before there were a lot of grades for that sort of thing;” … “If I had not had school, I probably would not have lived today … at school, I had a friend and I got food, that probably says it all about how I grew up.”

It was rather clear from the interviews with the participants, that they have had high absenteeism in school, often change of schools and teachers. “There were not many days I was in a class during secondary school” … “You can believe how many schools I have attended. In the end, I got tired of introducing myself” … “No teacher knew me” … “I did not help either so they would get to know me but the teachers did not even try to get to know me.” In the interviews several participants talked about how they had been bullied in compulsory school, but also how vulnerable they felt as poor readers. “I was teased for my hair, glasses, clothes yes just everything they [classmates] could think of – plus I could not read so well either – most of all I hated when I had to read aloud to everyone else [in the classroom]” … “If I only had ONE friend, I probably would have had it easier, but when you do not have a single … Yuk!! I do not want to talk about this …”

Discussion

There is an abundance of reading research among individuals staying at different kinds of correctional institutions. However, such research is exclusively about the prevalence of reading and writing disability among incarcerated and not reading interventions in a longitudinal perspective. This study aimed to bridge this research gap.

The main conclusions from the present longitudinal study are three-folded. First, there exists an obvious overrepresentation of difficulties with the written language among patients in forensic clinics (Svensson et al., Citation2015). Earlier studies have shown that difficulties in reading cause difficulties in getting a job (De Beer et al., Citation2014). Also, forensic psychiatric patients with low educational attainment tend to relapse in criminality (Krona et al., Citation2017) and have less opportunity to get a job and start studies (Kirsh et al., Citation2019). Subsequently, some researchers also conclude that it is important to increase incarcerated persons’ written language ability for a faster rehabilitation into society (Klinge & Dorsey, Citation1993; Selenius et al., Citation2021; Selenius & Hellström, Citation2015; Svensson, Citation2011). Second, the main study (Svensson et al., Citation2017) indicated that a short reading intervention substantially gained patients’ reading ability. The present study aimed to carry out a one-year-follow up, after a reading intervention, among patients admitted to forensic psychiatric care. Third, results show that participants still had the same reading ability after one year, as they had directly after the ending of the intervention.

One conclusion that can be drawn from the present study is that even a relatively short intervention (11 hours in total), not only clearly increases the patients’ reading ability, but that the improvement remains one year after completion. It also suggests that most participants did not have dyslexic reading difficulties, because they made clear progress after the intervention. This is uncommon among individuals with pure dyslexia since low or non-response from a reading intervention is a criterium for a diagnosis of dyslexia (DSM-5). Females’ scores increased more after reading interventions than those of males (Svensson et al., Citation2017). However, there was no difference in the follow-up, i.e. both women and men performed obtained similar results on the reading test at the follow-up. This study indicates that males need a more comprehensive effort to achieve a sufficiently good reading level. Previous studies have highlighted the importance of individualizing different types of interventions among persons with reading and writing difficulties (Duff & Clarke, Citation2011; Snowling & Hulme, Citation2012). In this study, the intervention was individualized for good reading development. Moreover, participants regarded these school-related tasks as meaningful and fun. Several patients highlighted the positives in getting full attention from the teacher during the intervention. The teacher’s support was described as important because patients felt encouraged, and they experienced success with school assignments. The results show that the individualized reading intervention yielded positive results, however, this is also related to how the special educator delivered the interventions. The importance of the teachers’ role has been pinpointed in several studies (Lee, Citation2012; Leko et al., Citation2015; Liebfreund & Amendum, Citation2017; Selenius et al., Citation2021; Taylor & Healy, Citation2001; Unrau et al., Citation2015) and it might be the most important factor regarding the development of reading ability for children and adults with reading difficulties as well as other kinds of school-related issues. Especially for individuals with very troublesome schooling and for those with learning disabilities. Consequently, the relationship between the student and the teachers is of high importance for academic achievement (Gorard, Citation2010; Lithari, Citation2019).

Furthermore, patients also emphasize the importance of having something to do at the institution. Many describe the boredom experienced in the departments, i.e. there are few daily meaningful planned activities.

Most patients describe that their earlier schooling has been fraught with failure, bullying, and not being seen by teachers; with similar experiences in their home environment. This accords with several previous studies (De Vogel et al., Citation2016; Karatzias et al., Citation2019; Selenius & Hellström, Citation2015). The results from this study can also be interpreted on the basis that patients have a capacity to learn linguistic elements, but that their previous schooling and home environment were fraught with problems and probably contributed to their difficulties with the written language. The findings from this study also highlight the importance of paying attention to students early in school, regardless of whether they have reading and writing difficulties and/or emotional shortcomings. Since an individual spends more than 10 years of their childhood and adolescence in school, it becomes an essential part of growing up. Experiencing constant failures during school time can lead to low school self-esteem and a poorer mental state. For the patients in this study, it is relevant to understand how their experience of school failure affected their mental state and if it contributed to the manifestation of their psychiatric diagnoses they have today.

The experience of school time is a significant factor regarding the choice of education in later life. In the present study, this is clearly reflected in the fact that majority of those who did not want to participate in the follow-up said that they were “done with everything that had to do with school.” Although they had improved their reading ability and experienced the interventions positively, they still did not want to do any more school assignments. Self-image may be destroyed quickly, but it takes a long time to build it up (Lithari, Citation2019). Therefore, a school activity is needed within these wards where they can work in a systematic and continuous way with various school-related tasks, a belief in their own abilities, and dare to carry out an education even outside the forensic psychiatric setting. Several previous studies have emphasized the importance of improving reading abilities among incarcerated persons to reduce the risk of future criminality and marginalization (Blomberg et al., Citation2011; Cottle et al., Citation2001; Leone & Wruble, Citation2015). In addition, offenders are also aware of their needs to be literate to participate in society (Wexler et al., Citation2015). The results from this study are promising as patients retained their improved reading ability one year after the intervention was completed. This was observed even though none of the participants had continued with any systematic reading training. However, despite the participants in this follow-up study showing that their reading ability had improved, the relatively large drop-out rate must be considered as a limitation. Therefore, the area has to be explored more thoroughly.

Conclusion

The present study describes the results from a follow up in a longitudinal reading study among patients at a forensic clinic. Results showed significant increases in reading ability, with a moderate to strong effect size, among patients after a short reading intervention period. After a one-year-follow up, the participants retained their reading level as that after the end of the interventions. Most participating patients testified about a difficult schooling with extensive truancy and being victims of bullying. Despite experiences of a difficult school time, the interventions, which were clearly reminiscent of schoolwork, were experienced as positive, because the patients had something to do at the institutions. The clinical pedagogical experience drawn from these results is that school activities based on these interventions need to be expanded to not only improve their ability to reintegrate into society, but to also have meaningful employment in this type of institution.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee [The present investigation has received ethical approval, Reference number: 96/05, by the Ethic Review Board in Linköping, (EPN) Sweden.] and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the individuals who took part in this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Alvarez, P., García-Carrión, R., Puigvert, L., Pulido, C., & Schubert, T. (2018). Beyond the walls: The social reintegration of prisoners through the dialogic reading of classic universal literature in prison. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 62(4), 1043–1061. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X16672864

- Blomberg, T. G., Bales, W. D., Mann, K., Piquero, A. R., & Berk, R. A. (2011). Incarceration, education and transition from delinquency. Journal of Criminal Justice, 39(4), 355–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2011.04.003

- Cottle, C. C., Lee, R. L., & Heilbrun, K. (2001). The prediction of criminal recidivism in juveniles. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 28(3), 367–394. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854801028003005

- De Beer, J., Engels, J., Heerkens, Y., & Van der Klink, K. (2014). Factors influencing work participation of adults with developmental dyslexia: A systematic review. BMC Public Health, 14(1), 77. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-77

- De Vogel, V., Stam, J., Bouman, Y. H. A., Ter Horst, P., & Lancel, M. (2016). Violent women: A multicentre study into gender differences in forensic psychiatric patients. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 27(2), 145. https://doi.org/10.1080/14789949.2015.1102312

- Duff, F. J., & Clarke, P. J. (2011). Practitioner review: Reading disorders: What are the effective interventions and how should they be implemented and evaluated? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 52(1), 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02310.x

- Fälth, L., Gustafson, S., Tjus, T., Heimann, M., & Svensson, I. (2013). Computer‐assisted interventions targeting reading skills of children with reading disabilities–A longitudinal study. Dyslexia, 19(1), 37–53. https://doi.org/10.1002/dys.1450

- Gorard, S. (2010). School experience as a potential determinant of post-compulsory participation. Evaluation & Research in Education, 23(1), 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500791003605110

- Grigorenko, E. L. (2006). Learning disabilities in juvenile offenders. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 15(2), 352–371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2005.11.001

- Karatzias, T., Shevlin, M., Pitcairn, J., Thomson, L., Mahoney, A., & Hyland, P. (2019). Childhood adversity and psychosis in detained inpatients from medium to high secured units: Results from the Scottish census survey. Child Abuse & Neglect, 96, 104094. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104094

- Kirsh, B., Martin, L., Hultqvist, J., & Eklund, M. (2019). Occupational therapy interventions in mental health: A literature review in search of evidence. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health, 35(2), 109–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/0164212X.2019.1588832

- Klinge, V., & Dorsey, J. (1993). Correlates of the Woodcock-Johnson reading comprehension and Kaufman brief intelligence test in a forensic psychiatric population. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 49(4), 593–598. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-4679(199307)49:4<593::AID-JCLP2270490418>3.0.CO;2-H

- Krezmien, M. P., & Mulcahy, C. A. (2008). Literacy and delinquency: Current status of reading interventions with detained and incarcerated youth. Reading and Writing Quarterly, 24(2), 291–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/10573560701808601

- Krona, H., Nyman, M., Andreasson, H., Vicencio, N., Anckarsäter, H., Wallinius, M., Nilsson, T., & Hofvander, B. (2017). Mentally disordered offenders in Sweden: Differentiating recidivists from non-recidivists in a 10-year follow-up study. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 71(2), 102–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/08039488.2016.1236400

- Lee, J.-S. (2012). The effects of the teacher–student relationship and academic press on student engagement and academic performance. International Journal of Educational Research, 53, 330–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2012.04.006

- Leko, M. M., Roberts, C. A., & Pek, Y. (2015). A theory of secondary teachers’ adaptations when implementing a reading intervention program. Journal of Special Education, 49(3), 168–178. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022466914546751

- Leone, P. E., Krezmien, M., Mason, L., & Meisel, S. (2005). Organizing and delivering empirically based literacy instruction to incarcerated youth. Exceptionality, 13(2), 89–102. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327035ex1302_3

- Leone, P. E., & Wruble, P. C. (2015). Education service in juvenile corrections: 40 years of litigation and reform. Education and Treatment of Children, 38(4), 587–604. https://doi.org/10.1353/etc.2015.0026

- Liebfreund, M. D., & Amendum, S. J. (2017). Teachers’ experiences providing one-on-one instruction to struggling readers. Reading Horizons: A Journal of Literacy and Language Arts, 56(4), 64–84. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/reading_horizons/vol56/iss4/5

- Lithari, E. (2019). Fractured academic identities: Dyslexia, secondary education, self-esteem and school experiences. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 23(3), 280–296. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2018.1433242

- Lundberg, I. (2010). Läsningens psykologi och pedagogik [The psychology and pedagogy of reading]. Natur & kultur.

- Metsala, J. L., David, M. D., & Brown, S. (2017). An examination of reading skills and reading outcomes for youth involved in a crime prevention program. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 33(6), 549–562. https://doi.org/10.1080/10573569.2016.1268081

- Selenius, H., Dåderman, A., Meurling, A. W., & Levander, S. (2006). Assessment of dyslexia in a group of male offenders with immigrant backgrounds undergoing a forensic psychiatric investigation. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 17(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/14789940500259952

- Selenius, H., Fälth, L., Svensson, I., & Strand, S. (2021). Educational needs among women admitted to high secure forensic psychiatric care. Journal of Forensic Psychology Research and Practice, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/24732850.2021.1973234

- Selenius, H., & Hellström, Å. (2015). Dyslexia prevalence in forensic psychiatric patients: Dependence on criteria and background factors. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 22(4), 586–598. https://doi.org/10.1080/13218719.2014.960069

- Snowling, M. J., Adams, J. W., Bowyer-Crane, C., & Tobin, V. (2000). Levels of literacy among juvenile offenders: The incidence of specific reading difficulties. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 10(4), 229–241. https://doi.org/10.1002/cbm.362

- Snowling, M. J., & Hulme, C. (2012). Annual research review: The nature and classification of reading disorders – A commentary on proposals for DSM-5. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 53(5), 593–607. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02495.x

- Statens beredning för medicinsk och social utvärdering [Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Service]. (2014). Dyslexi Hos Barn Och Ungdomar–Tester Och Insatser. En Systematisk Litteraturöversikt [Dyslexia in children and adolescents– Tests and interventions. Asystematic literature review]. (Mölnlycke: Elanders Sverige AB).

- Suggate, S. P. (2016). A meta-analysis of the long-term effects of phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, and reading comprehension interventions. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 49(1), 77–96. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022219414528540

- Svensson, I. (2011). Reading and writing disabilities among inmates in correctional settings. A Swedish perspective. Learning and Individual Differences, 21(1), 19–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2010.08.002

- Svensson, I., Fälth, L., & Persson, B. (2015). Reading level and the prevalence of a dyslexic profile among patients in a forensic psychiatric clinic. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 26(4), 532–550. https://doi.org/10.1080/14789949.2015.1037329

- Svensson, I., Fälth, L., Persson, B., & Nilsson, S. (2017). The effect of reading interventions among poor readers at a forensic psychiatric clinic. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 24(3), 440–457. https://doi.org/10.1080/13218719.2016.1247642

- Svensson, I., Lundberg, I., & Jacobson, C. (2001). The prevalence of reading and spelling difficulties among inmates of institutions for compulsory care of juvenile delinquents. Dyslexia, 7(2), 62–76. https://doi.org/10.1002/dys.178

- Taylor, J., & Healy, P. (2001). Education in secure psychiatric units. British Journal of Forensic Practice, 3(4), 3–7. https://doi.org/10.1108/14636646200100021

- Torgesen, J. K., Alexander, A. W., Wagner, R. K., Rashotte, C. A., Voeller, K. K., & Conway, T. (2001). Intensive remedial instruction for children with severe reading disabilities: Immediate and long-term outcomes from two instructional approaches. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 34(1), 33–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/002221940103400104

- Unrau, N., Ragusa, G., & Bowers, E. (2015). Teachers focus on motivation for reading: “it’s all about knowing the relationship. Reading Psychology, 36(2), 105–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/02702711.2013.836582

- Warnick, K., & Caldarella, P. (2016). Using multisensory phonics to foster reading skills of adolescent delinquents. Reading and Writing Quarterly, 32(4), 317–335. https://doi.org/10.1080/10573569.2014.962199

- Wexler, J., Reed, D. K., & Sturges, K. (2015). Reading practices in the juvenile correctional facility setting: Incarcerated adolescents speak out. Exceptionality, 23(2), 100–123. https://doi.org/10.1080/09362835.2014.986602