ABSTRACT

In North America, opioid-related deaths are on the rise. We report a case of pediatric cardiac toxicity likely related to illicit fentanyl ingestion. A 14-year-old male ingested half of an illicit pill. Two hours post-ingestion, the patient experienced loss of consciousness, hypotension, cyanosis and diaphoresis. He reported chest pain 8 hours post-hospital arrival. Initial lab reports revealed elevations in lactate and high-sensitivity troponin concentrations. A chest radiograph revealed a right-sided aspiration pneumonia. An electrocardiogram showed ST elevation over the anterior leads and T wave inversion over the inferior leads. An echocardiogram demonstrated borderline systolic function. Initial cardiac magnetic resonance imaging revealed inflammation. Comprehensive urine drug screen was positive for fentanyl and its metabolites, cannabinoids, ondansetron, metoclopramide and ranitidine and was negative for xylazine. The management included administration of non-invasive positive-pressure ventilation, naloxone, acetaminophen, ceftriaxone, and clindamycin. Hypotension was treated with calcium gluconate, dopamine, and norepinephrine. He was able to wean off inotropes the next day and went home 5 days post-presentation. A repeat cardiac MRI performed six months post-ingestion was normal. Illicit fentanyl use in an adolescent appeared to cause myocardial injury with cardiogenic shock, elevated serum troponins, and transient abnormalities on electrocardiography and cardiac imaging.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

In North America, there has been a dramatic increase in opioid-related deaths [Citation1,Citation2]. Fentanyl in particular has been implicated in at least 655 deaths in Canada between 2009 and 2014 [Citation3]. Opioids cause respiratory depression, which in turn may lead to severe hypoxemia and cardiac arrest. Direct cardiac toxicity is not a common manifestation of opioid overdose. We report a pediatric case of non-pharmaceutical fentanyl (NPF) ingestion with cardiac toxicity.

Case presentation

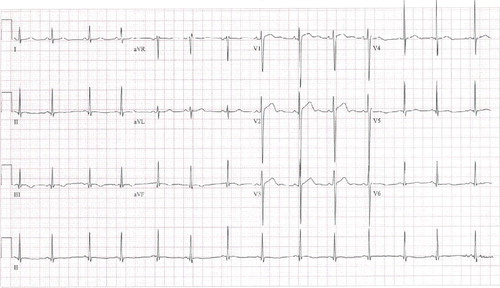

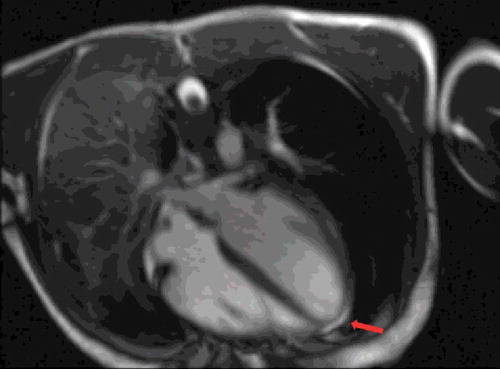

A 14-year-old male was found unresponsive, hypotensive, cyanotic (50% oxygen saturation on pulse oximetry) and diaphoretic. Two hours prior, he had ingested half of a round, blue-green unidentified pill. There was evidence of hematemesis on the patient's pillow with continued emesis en route to the hospital. An initial chest radiograph revealed right-sided aspiration pneumonia. Initial laboratory investigations showed a lactate of 6.4 mmol/L (0.5–1 mmol/L), glucose of 13.0 mmol/L (4–7 mmol/L), and a high-sensitivity troponin of 206 ng/L (1–14 ng/L). Acetaminophen and salicylate were undetectable. A comprehensive urine drug screen using gas chromatography– mass spectrometry was positive for fentanyl and its metabolites, cannabinoids, ondansetron, metoclopramide and ranitidine and negative for xylazine. He reported chest pain 8 hours post-hospital arrival. An ECG showed ST elevation over the anterior leads and T wave inversion over the inferior leads (), and an echocardiogram performed 20 minutes afterwards demonstrated borderline systolic function in both the right and left ventricles with a reported left ventricular ejection fraction of 55% by biplane method. A repeat ECG showed improvement in the ST elevations 5 hours after the initial one, while a repeat echocardiogram the following day had normal systolic function. High-sensitivity troponin peaked at 311 ng/L (normal 1–14 ng/L) within 24 hours whereas lactate normalized within a few hours post-presentation. Cardiac inflammation in the right coronary and left anterior descending arteries distribution possibly secondary to vasospasm was evident on a cardiac MRI performed two days post-hospital admission ().

Figure 1. An electrocardiogram taken at the time of chest pain showing ST elevation over the anterior leads and T wave inversion over the inferior leads.

Figure 2. Cardiac MRI; arrow indicating an area of epicardial inflammation at the apex of the left ventricle.

The management included administration of non-invasive positive-pressure ventilation, naloxone, acetaminophen (600 mg), ceftriaxone (1.5 g IV q 12 hours), and clindamycin (520 mg IV q 8 hours). Hypotension was initially treated with calcium gluconate (1 gram IV), dopamine (0–7.5 µg/kg/min), and norepinephrine (0–0.09 µg/kg/min IV) for goal mean arterial pressure >60 mm Hg. Approximately 24 hours post-admission, the patient was successfully weaned off inotropes and switched to room air a few days later. The patient was discharged home after five days of hospitalization. A repeat cardiac MRI performed six months post-presentation was normal and the patient appeared to have a full recovery.

Discussion

Opioids act at the mu-opioid receptors to cause potentially fatal respiratory depression. [Citation4]. Hypoxia can then lead to hypotension and bradycardia. A few specific opioid agents have other mechanisms of cardiac toxicity such as methadone causing QT prolongation and morphine inducing histamine release that may result in hypotension [Citation5]. Cardiac injury following opioid overdose may also occur due to co-ingestions or adulterations of drugs. Xylazine, a centrally acting α-2 agonist commonly used as a veterinary tranquilizer, was present in heroin, cocaine and fentanyl abuse cases that resulted in mortality [Citation6,Citation7]. Xylazine may cause hypotension, diffuse T-wave inversion on ECG, and elevation of cardiac biomarkers [Citation8]. A sympathomimetic agent such as cocaine contributes to cardiac toxicity. In this patient, a comprehensive urine drug screen was positive for fentanyl and its metabolite but negative for xylazine, cocaine and amphetamines. However, the patient did have detectable tetrahydrocannabinol and was known to be a habitual user of cannabis. Other possible causes that could have contributed to the cardiac toxicity include the presence of a cannabinoid effect or another unidentified cardiotoxic illicit substance.

Conclusion

Illicit fentanyl use in an adolescent appeared to cause myocardial injury with cardiogenic shock, elevated serum troponins, and transient abnormalities on electrocardiography and cardiac imaging.

Disclosure statement

We have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- As opioid overdose deaths reach record highs, call for systematic changes grows louder. ED Manage. 2016;28(2):13–19.

- Algren DA, Monteilh CP, Punja M, et al. Fentanyl-associated fatalities among illicit drug users in Wayne County, Michigan (July 2005–May 2006). J Med Toxicol. 2013;9(1):106–115.

- Deaths involving fentanyl in Canada, 2009–2014: Canadian Centre on substance abuse. 2015. Available from: http://www.ccsa.ca/ResourceLibrary/CCSA-CCENDU-Fentanyl-Deaths-Canada-Bulletin-2015-en.pdf

- White JM, Irvine RJ. Mechanisms of fatal opioid overdose. Addiction (Abingdon, England). 1999;94(7):961–972.

- Benyamin R, Trescot AM, Datta S, et al. Opioid complications and side effects. Pain Physician. 2008;11(2 Suppl):S105–S120.

- Wong SC, Curtis JA, Wingert WE. Concurrent detection of heroin, fentanyl, and xylazine in seven drug-related deaths reported from the Philadelphia Medical Examiner's Office. J Forensic Sci. 2008;53(2):495–498.

- Marinetti LJ, Ehlers BJ. A series of forensic toxicology and drug seizure cases involving illicit fentanyl alone and in combination with heroin, cocaine or heroin and cocaine. J Anal Toxicol. 2014;38(8):592–598.

- Carruthers SG, Nelson M, Wexler HR, et al. Xylazine hydrochloride (Rompun) overdose in man. Clin Toxicol. 1979;15(3):281–285.