ABSTRACT

A 20-year-old female at 36 weeks gestation ingested an unknown amount of diphenhydramine in a suicide attempt. She had a witnessed tonic-clonic seizure at home. Upon arrival to the emergency department, she was tachycardic with a pulse of 166, and confused. Fetal heart rate was 200–210 with poor variability. After being lavaged and given activated charcoal, the patient was given a small dose of intravenous physostigmine. Her pulse rapidly decreased from 134 to 121 beats/min and her mental status improved. The fetal pulse decreased from 192 to 182 b/m within 10 min. This case suggests that physostigmine can be used safely and effectively in pregnant women to treat signs and symptoms of severe anticholinergic poisoning in both the patient and fetus.

Introduction

Antihistamines are the fourth most common pharmaceutical class taken in overdose [Citation1]. Anticholinergic signs and symptoms often predominate [Citation2]. Antihistamines also appear to cross the placenta, possibly causing anticholinergic toxicity in the fetus, manifesting primarily as tachycardia [Citation3]. Physostigmine, the principal antidote for severe anticholinergic toxicity, crosses the placenta [Citation4,Citation5]. Following a report of two cases published in 1980 that attributed adverse outcomes to physostigmine used in tricyclic antidepressant overdose, its overall use, even in the toxicology community, declined [Citation6,Citation7]. A 2003 review article refuted the fears surrounding physostigmine use [Citation8]. Momentum is developing towards more frequent administration of this useful antidote [Citation7–10]. However, there is limited evidence of its use in maternal/fetal anticholinergic toxicity. We report a case in which physostigmine decreased both maternal and fetal tachycardia and temporarily reversed maternal anticholinergic delirium.

Case report

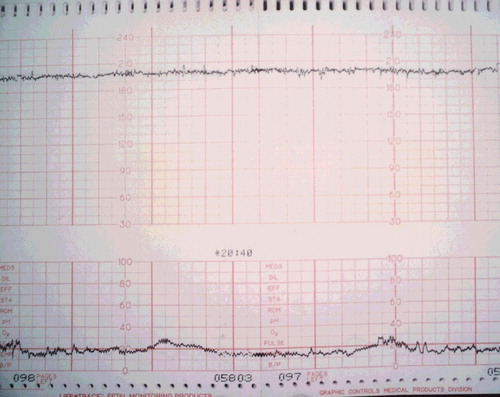

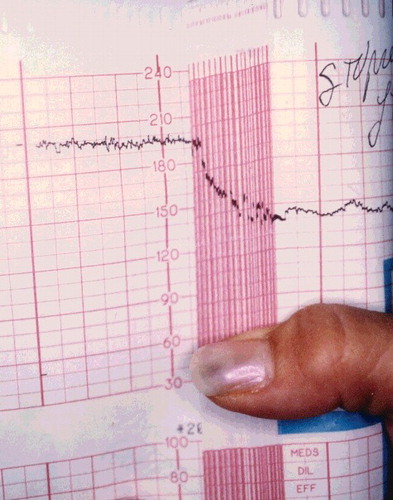

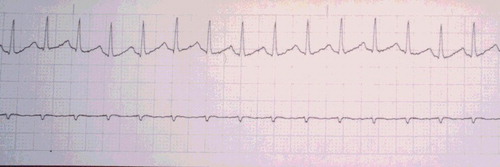

A 20-year-old woman, G1P0, at 36 weeks gestation, arrived to the emergency department approximately 2 hours after attempting suicide with an unknown amount of diphenhydramine (Compoz® and Unisom®) and hydroxyzine. Prior to arrival, she had a generalized tonic-clonic seizure at home, which lasted approximately 3 min. On ED presentation, the patient was confused and appeared to be having visual hallucinations. Her speech was incoherent, and she could not provide any history. She had a maximum pulse of 166, and cardiac monitor showed a narrow-complex sinus tachycardia (). Her blood pressure was 140/78, respiratory rate 20, and temperature 98.3 °F. Her pupils were 4–5 mm and reactive. Fetal monitoring showed a heart rate of 200–210 beats/min with poor variability (). External uterine monitoring showed mild irregular contractions, which fortunately did not progress to active labor. She received 1-mg dose of physostigmine IV over 5 min. Her pulse decreased from 134 to 121 beats/min, and she became coherent and was able to answer questions appropriately within 5 min. No further physostigmine was necessary because an accurate history was available during her lucid interval, and both the mother and fetus had a favorable hemodynamic response. The fetal heart rate decreased from 192 to 182 beats/min within 10 min of the injection. Normal fetal heart rate (140 beats/min) returned within 5–6 hours post ingestion (). Mild anticholinergic delirium, along with sedation, recurred in the patient about an hour after receiving physostigmine, but did not require further treatment. Maternal tachycardia persisted nearly twice as long as fetal tachycardia, with resting heart rate >100 until approximately 12 hours post ingestion. All maternal symptoms resolved within 24 hours. Urine toxicology testing confirmed “large amount of diphenhydramine and metabolite” by chromatography and mass spectrometry. At 39 weeks gestation, she delivered a healthy female infant weighing 6 lb 14 oz (3118 g), with Apgar scores of 9 at 1 and 5 min.

Figure 1. Maternal rhythm strip showing narrow complex sinus tachycardia 2 hr and 15 min post ingestion.

Discussion

Antihistamines are the eighth most common drug class involved in poison exposures in pregnant patients [Citation1]. Antihistamines block acetylcholine at muscarinic receptors resulting in anticholinergic signs and symptoms, including tachycardia, mydriasis, dry and flushed skin, urinary retention, agitation, delirium, and hallucinations [Citation2].

Although there are no reports in the literature of antihistamine toxicity in a fetus due to maternal overdose, evidence suggests that diphenhydramine crosses the placenta, and therefore may cause toxic effects on the fetus, including tachycardia and loss of beat-to-beat variability [Citation4,Citation5]. Placental transfer of diphenhydramine occurs in sheep [Citation3]. Diphenhydramine infusions demonstrated several effects in the fetal lamb. Low doses produced sedation, reduced REM sleep, and reduced breathing activity; higher doses led to hypoxemia, acidemia, tachycardia, and transiently increased breathing activity. As seen in our patient, diphenhydramine and its chlorotheophylline salt, dimenhydrinate (Dramamine®) can exert oxytocic effects [Citation11–Citation13]. A study of dimenhydrinate in human labor (100 mg IV over 3.5 min) demonstrated increased amplitude and frequency of contractions. A few patients also experienced uterine hyperstimulation and fetal compromise. Two patients developed uterine tetany accompanied by fetal bradycardia and loss of beat-to-beat variability [Citation14]. One overdose of diphenhydramine by a woman in her 26th week of pregnancy resulted in premature labor, which was successfully treated with magnesium sulfate [Citation15].

Treatment of antihistamine overdose is primarily supportive, however physostigmine is useful in cases of severe central anticholinergic toxicity [Citation2,Citation7,Citation10]. Physostigmine is a reversible acetylcholinesterase inhibitor. It is a tertiary amine and therefore crosses into the central nervous system to reverse the central as well as peripheral effects of anticholinergic agents [Citation16]. This ability to cross the blood–brain barrier suggests that it can to cross the placenta as well [Citation3]. Boehm et al. [Citation5] described using physostigmine to reverse the effects of therapeutic administration of anticholinergic agents in gravid patients, and in our overdose case presented above. No reports linking physostigmine to congenital defects have appeared, and it is rated FDA Risk Factor C [Citation17]. Experience in pregnancy remains limited. Excessive or repetitive doses may lead to cholinergic toxicity in the mother or fetus, including bradycardia, seizures, hypersalivation, and bronchospasm. We recommend consultation with a clinical toxicologist or poison control center.

Conclusion

Physostigmine was effective in treating severe anticholinergic toxicity in a mother and fetus.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Gummin DD, Mowry JB, Spyker DA, et al. 2016 annual report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ national poison data system (NPDS): 34th annual report. Clin Toxicol. 2017;55:1072–1252.

- Whyte IM. Sedating antihistamines. In: Dart RC, editor. Medical toxicology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia (PA): Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004. p. 396–400.

- Yoo SD, Axelson JE, Taylor SM, et al. Placental transfer of diphenhydramine in chronically instrumented sheep. J Pharm Sci. 1986;75:685–687.

- Briggs GG, Freeman RK, Yaffe SJ. Drugs in pregnancy and lactation. 10th ed. Philadelphia (PA): Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2015.

- Boehm FH, Egilmez A, Smith BE. Physostigmine's effect on diminished fetal heart rate variability caused by scopolamine, meperidine, and propiomazine. J Perinat Med. 1977;5:214–222.

- Pentel P, Peterson CD. Asystole complicating physostigmine treatment of tricyclic antidepressant overdose. Ann Emerg Med. 1980;9:588–590.

- Burns MJ, Linden CH, Graudins A, et al. A comparison of physostigmine and benzodiazepines for the treatment of anticholinergic poisoning. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;35:374–381.

- Suchard JR. Assessing physostigmine's contraindication in cyclic antidepressant ingestions. J Emerg Med. 2003;25:185–191.

- Schneir AB, Offerman SR, Ly BT, et al. Complications of diagnostic physostigmine administration to emergency department patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;42:14–19.

- Watkins JW, Schwarz ES, Arroyo-Plasencia AM, et al. The use of physostigmine by toxicologists in anticholinergic toxicity. J Med Toxicol 2015;11:179–184.

- Rotter CW, Whitaker JL, Yared J. The use of intravenous Dramamine to shorten the time of labor and potentiate analgesia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1958;75:1101–1104.

- Shephard B, Crus A, Spellacy W. The acute effects of Dramamine on uterine contractility during labor. J Reprod Med. 1976;16:27–28.

- Watt LO. Oxytocic effects of dimenhydrinate in obstetrics. CMAJ. 1961;84:533–534.

- Hara GS, Carter RP, Krantz KE. Dramamine in labor: potential boon or possible bomb ? J Kans Med Soc. 1980;81:134–136.

- Brost BC, Scardo JA, Newman RB. Diphenhydramine overdose during pregnancy: Lessons from the past. Am J Obst Gyn. 1996;175:1376–1377.

- Shannon M. Toxicology reviews: physostigmine. Ped Emerg Care. 1998;14:224–226.

- Bailey B. Are there teratogenic risks associated with antidotes used in the acute management of poisoned pregnant women? Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2003;67:133–140.