Abstract

Agomelatine is a melatonin receptor agonist (MT1 and MT2) and 5-HT2c receptor antagonist. It is used as an antidepressant. There is limited information regarding agomelatine toxicity in overdose. This study analyzed calls to the Victorian Poisons Information Centre (VPIC) to further define agomelatine toxicity in poisoned patients. This was a retrospective review of calls to VPIC from May 2011 to May 2018. The VPIC database was interrogated for the terms “agomelatine”, “Valdoxan®” and “antidepressant” and call records extracted. Calls not related to agomelatine exposure were excluded. Patient demographics, reported symptoms, ingested dose, poisoning severity scores and intent were analyzed. There were 99 agomelatine-related calls during the study period. Most calls were related to intentional overdose (n = 72, 72.7%). The majority of these were polydrug overdoses (n = 56, 77.8%). There were 16 (22%) cases of sole agomelatine overdose and most patients reported to be asymptomatic (60%, n = 9). Other patients developed drowsiness (31.3%), dizziness (6.3%) or nausea (6.3%) at a median of 1.63 h (IQR 0.46, 4.25) post ingestion. Findings suggest that sole agomelatine ingestion can result in drowsiness, dizziness, or nausea. More severe toxicity has been reported with polydrug overdose.

Introduction

Depression is a common mental disorder with more than 300 million people estimated to be suffering from the condition [Citation1]. Alongside psychological treatments, there is a diverse range of medications available for the treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD). Agomelatine is a newer generation antidepressant currently available for the treatment of MDD in Australia and the European Union. It is currently indicated for adults and the recommended therapeutic dose is 25–50 mg once daily [Citation2].

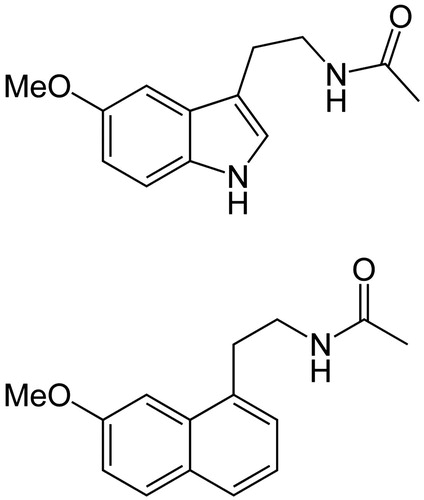

Agomelatine is a melatonin analogue with a unique pharmacokinetic profile. It is a melatonin (MT1 and MT2) receptor agonist and has a similar chemical structure (). It is also a 5-HT2c receptor antagonist which increases dopamine and noradrenaline activity, and resynchronizes circadian rhythm to improve mood and sleep quality, respectively [Citation3].

There is limited information regarding the effects of agomelatine in overdose. The aim of this study was to describe agomelatine-related toxicity reported to the Victorian Poisons Information Centre (VPIC).

Methods

This study was a retrospective review of agomelatine poisonings reported to VPIC. The VPIC receives poison exposure calls within the state of Victoria, Australia, which has a population of almost six million people. Every call to the VPIC is documented in a purpose-designed electronic database. Recalls to the poison center are documented in the database, but generally outcome data is not available. All data in the VPIC database are de-identified.

The VPIC database was interrogated by the two study investigators for the terms “agomelatine”, “Valdoxan®” and “antidepressant”. Calls not related to agomelatine exposure were excluded. We extracted agomelatine-related calls between May 2011 and May 2018. The narrative description of the call for each case identified was then accessed. Electronic preformatted case reports were generated for each case identified and transferred to an electronic spreadsheet.

Data points collected

For each VPIC case meeting the inclusion criteria, we extracted the following data: date and time of call, patient gender, age, designation of the caller (patient, family, friend, career, doctor, nurse, etc.), intentional or accidental exposure, route of exposure, dose, time since exposure, symptomology, Poisoning Severity Score (PSS) [Citation4] and advice given.

Calls were categorized into intentional overdose, misuse, therapeutic error or accidental ingestion. In this study, “misuse” refers to the use of a medication outside the reason it was prescribed and encompasses the terms “diversion”, “off-label use” and “recreational abuse”.

We analyzed all data descriptively using medians, interquartile ranges and percentages. Excel (Version 14.00, 2010; Microsoft, United States) was used to analyze the data.

Results

There were a total of 99 agomelatine-related calls over the seven-year period. There was an increase in the total number of exposures from 2011 (2 calls) to 2016 (41 calls). More than half of the calls were from doctors (55%). Most of the patients were being assessed in hospital at the time of the call (64%) ().

Table 1. Demographic and poisoning information from agomelatine-related calls to VPIC.

The majority of agomelatine calls were related to intentional overdose (73%). Females were more likely to overdose (n = 44, 61%) than males (n = 28, 39%). The majority of overdose cases were adults (n = 56, 78%). The youngest age reported in overdose was 15 years old. Overall, the maximum dose reported in overdose was 7.5 g and the median dose ingested was 288 mg (IQR 175, 681). There was one call related to misuse for its sedative effects.

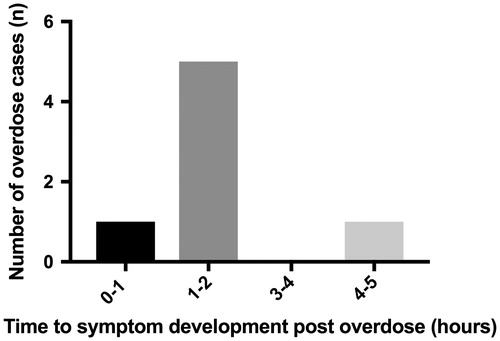

There were 16 cases of sole intentional agomelatine overdose and most patients reported to be asymptomatic (60%, n = 9). These ingestions occurred at a median of 10 min (IQR 5, 19) prior to the call. Symptoms developed from sole-agomelatine ingestion included drowsiness (44%, n = 5), dizziness (6%, n = 1) and nausea (6%, n = 1). These occurred at a median time of 1.63 h (IQR 0.46, 4.25) () and median ingested dose of 250 mg (IQR 150, 625) in adults. The smallest ingested dose causing drowsiness was 175 mg. All cases who developed drowsiness were managed supportively without need for intubation. Vital signs were recorded as within the normal range for all sole agomelatine ingestions. Three of the 16 cases had follow up calls (>4 h post ingestion) and all had remained asymptomatic. All intentional overdoses were managed in hospital or referred to hospital. Supportive management was advised for all cases.

In addition to the sole agomelatine overdose cases, there were five sole accidental ingestions in patients all under the age of 10. Median time to call from ingestion was 10 minutes (IQR 2.5, 15). Median ingestion dose was 12.5 mg (12.5 mg, 25 mg). All were asymptomatic at time of call and asked to remain at home unless they became symptomatic. Two of the five cases had a follow-up call 4 h post ingestion and they remained asymptomatic.

The majority (n = 56, 78%) of overdose calls related to polydrug ingestions. Antidepressants other than agomelatine (50.0%) were the most common co-ingestants. There were two severe cases that resulted from polydrug overdoses: one patient had profound central nervous system (CNS) depression and the other patient experienced pulseless electrical activity (PEA) arrest, and was subsequently intubated. Both of these cases were associated with co-ingestion of respiratory depressant medications. The patient with the highest reported dose ingested (7.5 g, co-ingested with escitalopram 700 mg, call taken 9 h post overdose) manifested with drowsiness and a mild tachycardia.

Discussion

Our study revealed that symptoms developed from sole-agomelatine overdose were drowsiness, dizziness and nausea. These symptoms are consistent with agomelatine’s mechanism of action and adverse effects profile outlined by therapeutic usage [Citation3]. However, the majority of calls from sole-ingestions were made early and involved smaller doses of agomelatine. This likely resulted in them being asymptomatic at time of call.

The majority of overdoses involved multiple medications. The largest ingestion of 7.5 g of agomelatine was co-ingested with escitalopram and developed drowsiness. As escitalopram overdose is not typically associated with decreased conscious state, this was likely due to the melatonin agonistic effects of agomelatine. Similarly, disorientation has been associated with melatonin agonists previously [Citation5]. In addition, there have been cases of agomelatine-induced liver transaminase rise in the literature (up to 4% of therapeutic ingestions) [Citation6], however this was not reported in our study. To our knowledge, there have not been any published case reports of agomelatine overdose.

In our study, agomelatine was commonly ingested with other antidepressants in overdose. Currently there are no guidelines on combination therapy of agomelatine and other antidepressants for MDD. Agomelatine may be safe in combination with serotoninergic medications as it does not increase serotonin activity [Citation7]. Agomelatine undergoes metabolism via cytochrome P450 1A2 and 2C9 isoenzymes. Hence, use of CYP1A2 inhibitors such as fluvoxamine and ciprofloxacin, may increase agomelatine concentrations [Citation8]. Therapeutic studies of agomelatine report that absorption is rapid with a median tmax of 0.75–1.5 h and 80% intestinal absorption [Citation9]. There is extensive first pass metabolism of agomelatine, it has a bioavailability of 1% in therapeutic use and a mean elimination half-life of 2.3 h [Citation3, Citation10].

There are several limitations of our study. The accuracy of VPIC data depends on a reliable history provided by the caller and provides only a snapshot of the case at that time. Doses ingested may be under or overestimated and ECGs were not acquired. In addition, the majority of cases had no outcome data. Future studies should aim to prospectively capture information on agomelatine overdose and use.

Conclusions

Sole-agomelatine ingestion can result in drowsiness, dizziness or nausea. More severe clinical symptoms can result from polydrug ingestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Word Health Organisation. Depression Fact Sheet. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs369/en/.

- Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). Australian public assessment report for agomelatine. In: Administration DoHaATG, editor. Australia: Australian Government; 2010. p. 87.

- Servier Laboratories. Valdoxan – Product information 2016. http://www.servier.com.au/products.

- Persson HE, Sjoberg GK, Haines JA, Pronczuk de Garbino J. Poisoning severity score. Grading of acute poisoning. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1998;36(3):205–13.

- Holliman BJ, Chyka PA. Problems in assessment of acute melatonin overdose. South Med J. 1997;90(4):451–3.

- Freiesleben SD, Furczyk K. A systematic review of agomelatine-induced liver injury. J Mol Psychiatry. 2015;3(1):4.

- Horgan D, Dodd S. Combination antidepressants: use by GPs and psychiatrists. Aust Family Phys. 2011;40(6):397–400.

- Agomelatine. Australian Prescriber. 2010;33(5):160–3.

- Wang X, Zhang D, Liu M, Zhao H, Du A, Meng L, et al. LC–MS/MS method for the determination of agomelatine in human plasma and its application to a pharmacokinetic study. Biomed Chromatogr. 2014;28(2):218–22.

- Kennedy SH, Eisfeld BS. Agomelatine and its therapeutic potential in the depressed patient. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2007;3(4):423–8.