Abstract

A 26-year-old man presented to the Emergency Department with lower urinary tract symptoms. He had a history of chronic ketamine abuse by sniffing over the last 6 years, with a recent increase in ketamine consumption. Acute kidney injury was related to bilateral hydronephrosis with dilatation of both ureters and irregularly thickened bladder walls. Laboratory investigations also revealed a marked hyponatremia and a major increase in liver enzymes consistent with a cholestatic injury. Finally, a pneumomediastinum was also diagnosed on the thoracic computed tomography. All these manifestations regressed after cessation of ketamine exposure. Chronic ketamine abuse may be associated with multiorgan toxicity. In particular, ketamine cystitis may be followed by obstructive complications leading to acute renal failure.

Introduction

Long-term ketamine abuse has a particularly high incidence of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) and affects more than 50% of ketamine abusers [Citation1]. While most of ketamine abusers are experiencing mild symptoms, progression to acute renal failure may occasionally occur as a consequence of ureterovesical obstruction. Hepatobiliary injury is also a matter of concern. This case, presented in accord with the CARE guidelines, illustrates the urological and hepatobiliary toxicity of chronic ketamine toxicity with improvement following supportive care and cessation of ketamine use.

Case presentation

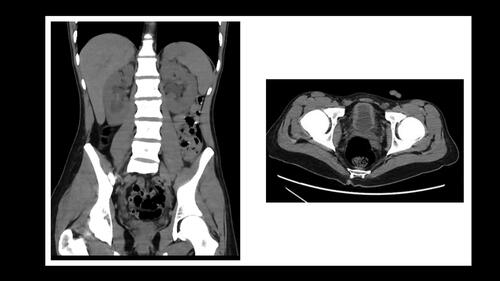

A 26-year-old man presented to the Emergency Department with increased urinary frequency that started two months before, and with recent nocturia, sense of incomplete bladder emptying and hematuria. He had a history of chronic recreational abuse of ketamine over the last six years, with a current increase of intranasal abuse (daily “snorting” of 5–10 g). He was smoking 10 cigarettes per day, but denied ethanol abuse. He also noticed a recent weight loss of 12 kg, with asthenia and anorexia. Results of laboratory investigations, including baseline values obtained four weeks before hospital admission appear in and mainly revealed an acute kidney injury (KDIGO III) with hematuria, aseptic leukocyturia, mild proteinuria, hyponatremia, and elevated hepatic enzymes indicating biliary obstruction. Thoracic and abdominal computed tomography (CT) revealed a pneumomediastinum with subcutaneous neck emphysema (), no changes in hepatic morphology, and bilateral hydronephrosis with dilatation of both ureters and irregularly thickened bladder walls ().

Figure 1. Thoracic computed tomography (CT) (sagittal view) with pneumomediastinum and subcutaneous neck emphysema.

Figure 2. Abdomen CT (coronal view) showing bilateral hydronephrosis and irregular thickening of bladder walls (transversal view).

Table 1. Laboratory investigations before and during hospital stay, and at follow-up.

Treatment included urinary catherization, intravenous fluids, analgesics, and abstinence from ketamine; no specific treatment was required for pneumomediastinum. Urine output was 1080 mL during the first 24 h. Acute renal dysfunction and hyponatremia resolved within 2 weeks. The urinary catheter was removed after 72 h. Starting from hospital day 6–7, urinary complaints decreased (urinary emission every hour instead of every 15 min). Abdominal ultrasound examination on hospital day 5 showed no signs of biliary dilatation. Serology testing excluded Infectious or auto-immune causes of acute hepatitis. At laboratory follow-up, alkaline phosphatase and gamma-glutamyl-transferase gradually decreased over the eight following weeks but did not completely return to normal. The indication of liver biopsy was delayed, but an ultrasound examination using transient elastrography technology (Fibroscan®) was planned. The patient agreed to join a ketamine cessation program.

The Naranjo score is 7 and indicates a “probable” relationship between ketamine abuse and this triad of symptoms [Citation2].

Discussion

Ketamine recreational use is rising among young populations over the last 20 years [Citation3]. Simultaneously, an association between urological symptoms (increased frequency, urgency, nocturia, small volume voids, dysuria, urgency incontinence, sense of incomplete bladder emptying, pelvic pain, and hematuria) and ketamine abuse has appeared. This has led to the identification of ketamine-induced interstitial ulcerative cystitis, known as “ketamine cystitis (KC)”. Even though etiology remains unclear, there is histological evidence of bladder inflammation, fibrosis and nerve hyperplasia [Citation1]. Although KC prevalence remains unknown, epidemiological studies have shown that 27 to 84% of ketamine abusers report at least one lower urinary tract symptom (LUTS) [Citation4–5]. The development of LUTS has a positive correlation with the duration of ketamine abuse and “snorting” seems associated with a higher prevalence than smoking [Citation4]. The diagnosis of KC is usually suspected by anamnesis, linking LUTS with ketamine abuse. Imaging studies might reveal bladder wall thickening, calcifications, and upper urinary tract involvement with ureteral wall thickening and hydronephrosis. Urodynamics studies typically show increased bladder sensitivity, detrusor overactivity, low compliance, and decreased bladder capacity. In severe cases of bladder fibrosis, urodynamics studies might also show vesicoureteral reflux. Endoscopy usually reveals ulcerative cystitis. Ketamine may damage the kidney as well, causing interstitial nephritis and papillary necrosis. The differential diagnosis of KC includes interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome with similar complaints [Citation6]. This latter syndrome more frequently appears in women, and its pathophysiology is still debated. Treatment of KC is mainly based on ketamine cessation. Medical treatment aims to achieve pain relief, reduce inflammation, and stop the progression to upper urinary tract involvement. However, for severe cases, cystectomy and bladder reconstruction might be necessary.

Hepatobiliary abnormalities were present in 9.8% of 297 ketamine chronic abusers with urinary tract dysfunction [Citation7]. Cholangitis was the most apparent feature in the seven patients who underwent liver biopsy. As in our case, the simultaneous elevation of C-reactive protein (CRP) was noted in the absence of a clear infectious etiology. Although the mechanism of hepatobiliary injury remains unclear, Wong et al. suggested two different pathological pathways: parenchymal injury with bile ductular damage and injury to the smooth muscle of Oddi’s sphincter leading to large bile duct dilatation. Reversibility seems possible after ketamine cessation, but bridging liver fibrosis has occurred in some patients.

Pneumomediastinum has been infrequently appeared after ketamine snorting and may result from sudden increase in intra-alveolar pressure following a Valsalva’s maneuver during insufflation of ketamine [Citation8]. Two other case reports illustrate this triad of pneumomediastinum, elevated alkaline phosphatase and hydronephrosis in young ketamine abusers [Citation9–10].

Our observation illustrates that chronic ketamine abuse may be associated with multiple organ injury. The concomitant regression of CRP, signs of cholangitis, and urinary tract dysfunction would support the hypothesis of a common inflammatory process. Abstinence is the key for symptoms resolution.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no declarations of interest.

References

- Castellani D, Pirola GM, Gubbiotti M, et al. What urologists need to know about ketamine-induced uropathy: A systematic review. Neurourol Urodyn. 2020;39(4):1049–1062.

- Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30(2):239–245.

- Larabi IA, Fabresse N, Etting I, et al. Prevalence of New Psychoactive Substances (NPS) and conventional drugs of abuse (DOA) in high risk populations from Paris (France) and its suburbs: A cross sectional study by hair testing (2012-2017). Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;204:107508.

- Li CC, Wu ST, Cha TL, et al. A survey for ketamine abuse and its relation to the lower urinary tract symptoms in Taiwan. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):7240.

- Winstock AR, Mitcheson L, Gillatt DA, et al. The prevalence and natural history of urinary symptoms among recreational ketamine users. BJU Int. 2012;110(11):1762–1766.

- Patnaik SS, Laganà AS, Vitale SG, et al. Etiology, pathophysiology and biomarkers of interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2017;295(6):1341–1359.

- Wong GL, Tam YH, Ng CF, et al. Liver injury is common among chronic abusers of ketamine. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(10):1759–1762.e1.

- Caceres M, Ali SZ, Braud R, et al. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum: a comparative study and review of the literature. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;86(3):962–966.

- Williams J, Hsu E, Flamer-Caldera A, et al. The Special K Constellation, a rare presentation of ketamine use: a case report. Cureus. 2019;11(5):e4766.

- Wong O, Kwan G, Tsang P, et al. Pneumomediastinum, surgical emphysema and pneumorrhachis after insufflation of ketamine. Hong Kong J Emerg Med. 2013;20(1):50–52.