Abstract

Ingesting sodium nitrite as a suicide method appears to be gaining popularity, spurred by online suicide blogs and an easily obtainable product. However, the exact nature of this trend has not been studied. We conducted an 11-year retrospective review of intentional sodium nitrite ingestions reported to the National Poison Data System from January 1, 2009-December 31, 2019. We included all cases coded as “nitrite or nitrate” in the initial request. We requested full case records for the initial cohort to confirm details. NPDS recorded 390 individual “nitrite or nitrate” exposures during the study period, and 42 met inclusion criteria. We received full case records for 35/42 patients, and 17 were included in the final cohort (N = 17). The mean age was 23.2 years old. Visible cyanosis was present in 13/17 patients with a mean oxygen saturation of 85%. Methylene blue was administered in 14/17 cases with 8/17 requiring advanced cardiac life support. The overall mortality rate was 41% (7/17). All patients presented in the final two years of the study period. Intentionally ingesting sodium nitrite represents a novel, growing trend and carries a high mortality rate among young adults.

Abbreviations: AAPCC, American Association of Poison Control Center; ACLS, Advanced Cardiac Life Support; CPCS, California Poison Control System; NPDS, National Poison Data System; PCC, Poison Control Center; SPI, Specialist in Poison Information.

Introduction

Sodium nitrite is a white crystalline salt with a variety of uses in industry, food preservation, and in the treatment of cyanide toxicity. When ingested, it is a powerful oxidizing agent, leading to the generation of methemoglobinemia and hemolysis [Citation1]. Nitrite exposure can also cause vasodilation and hypotension through the generation of nitric oxide [Citation2]. The majority of previously published sodium nitrite exposures were unintentional, and in some cases fatalities were reported [Citation3,Citation4]. However, intentional sodium nitrite ingestions for the purpose of suicide are infrequently reported in the literature [Citation5–7].

We recently published a case series of intentional sodium nitrite exposures reported to the California Poison Control System (CPCS) that resulted in two cases of severe toxicity and three deaths [Citation8]. The cases occurred over a 7-month period in 2019 and raised concern for an emerging trend for the use of this substance as a method of suicide. To further investigate and define this potential trend, we designed an 11-year retrospective review of intentional sodium nitrite ingestions utilizing the larger and geographically diverse American Association of Poison Control Center’s (AAPCC) National Poison Data System database (NPDS).

Methods

This is an 11-year retrospective review of all cases of intentional sodium nitrite ingestion exposures reported to the NPDS from 1 January 2009 to 31 December 2019. The NPDS database prospectively collects data on all exposures reported to the 55 poison control centers throughout the United States and US territories. Specialists in poison information (SPI) code each individual case in a standardized database that includes both fixed data fields and a single free-text field. Fixed data fields include demographic information, specific substance codes, reason for the exposure (e.g. intentional, unintentional, or adverse reaction), route, amount of exposure, clinical effects, interventions, and medical outcomes. These data are stored at each individual PCC and automatically uploaded to the centralized NPDS database at regular intervals.

We queried the NPDS database for all exposures involving the AAPCC generic category code for “nitrites or nitrates” 034260, which includes any product that contains a nitrite or nitrate compound [Citation9]. Our goal in using this broad generic category code in our initial search was to ensure that we received the largest and most complete data set, and we did not unintentionally exclude potential patients in the initial search. We did not use the specific product code for sodium nitrite in the search to avoid either including inappropriate cases or missing cases due to coding errors. In the initial query, we included both exposure and information cases, single or multiple drug cases, and all reasons for exposure. Two of the authors, AM and JAL, manually reviewed the initial NPDS data set to identify the final cohort. We excluded cases where the reason for exposure was coded as unintentional, adverse reaction, or intentional abuse or misuse. We included all cases in which the reason for exposure was coded as intentional (suspected suicide or unknown) or as unknown, single or multiple drug exposures, and in which the route of exposure was ingestion or unknown. We then requested patient case records from individual PCCs to confirm details, inclusion criteria, specifically that the product was sodium nitrite, and to review the free text field. All records were de-identified to maintain confidentiality. A standardized extraction form was used to collect all relevant demographic data and case details. The study was deemed to be exempt from institutional review board (IRB) and was approved by the AAPCC. Descriptive statistics are reported.

Results

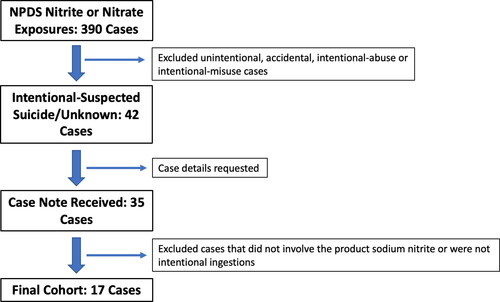

Over the 11-year study period, there were 390 individual nitrite or nitrate exposures reported to the NPDS. After excluding all unintentional, accidental, intentional-abuse, and intentional-misuse exposures, 42 patients remained. These 42 patients were coded as intentional-suspected suicide (25 patients), intentional-unknown (five patients), or unknown (12 patients). Details of these 42 patients were then requested from individual poison centers, and we received records for 35 (83%, 35/42 cases).

After reviewing the free text details of the 35 patients, we confirmed that 20 involved the product sodium nitrite. The products in the remaining 15 cases were amyl nitrite, isobutyl nitrite, sodium nitrate, or other nitrate-containing substances. A further three cases were excluded as one was an accidental ingestion of a home remedy, one was a questionable intravenous exposure, and the third was an information call regarding only a potential exposure. Therefore, the final cohort included 17 patients from the following states: Connecticut, Colorado, Nebraska, Oregon, Michigan, Georgia, Missouri, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Washington, Wisconsin, California, and Washington D.C. illustrates how the final cohort of patients was established.

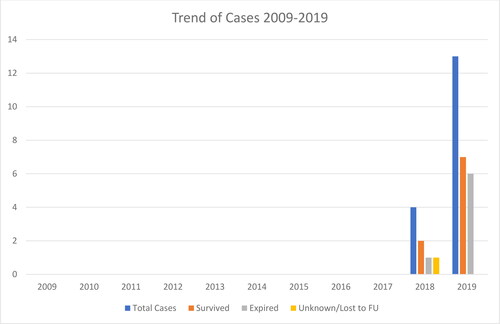

Characteristics of the exposures are shown in . The mean age of the cohort was 23.2 years old and was almost evenly split between male and female patients. The amount of product ingested was reported in 71% of the patients (12/17) and while the range was from 250 mg to 907 g, most patients reported ingesting over 15 g. The majority of patients presented with visible cyanosis (76%, 13/17) and had a mean oxygen saturation of 85%. Methemoglobin concentrations were reported in 59% of the cases (10/17), although an absolute value was not available in two cases and were only reported as being above the upper limit of detection for the machine. Methylene blue was administered to 82% (14/17), with 2 mg/kg the most commonly administered dose. In eight cases, it was confirmed, either by the patient themselves or by suicide notes at the scene, that they had researched this specific method of suicide online. Intubation and advanced cardiac life support (ACLS) were each used in 47% of cases (8/17, respectively). The overall mortality rate amongst this cohort was 41% (7/17), and one patient was lost to follow up. All of the patients requiring ACLS ultimately died or were lost to follow up. Notably, all cases of sodium nitrite ingestion occurred in the final 2 years of the study period. highlights the number of patients and their respective outcomes by year.

Table 1. Demographics and case details.

Discussion

In this 11-year retrospective review of intentional sodium nitrite ingestions reported to the National Poison Data System, we identified a final cohort of 17 patients meeting inclusion criteria, all of which occurred in the final two years of the study period. In addition, with a mortality rate of 41%, sodium nitrite ingestions were associated with significant mortality. Finally, there was a 3-fold increase in reported cases between 2018 and 2019, suggesting that sodium nitrite ingestion as a means of suicide is a growing trend. Similar trends have been observed in France, with a recent report showing four cases of intentional sodium nitrite ingestion reported to the French National Database of Poisoning in 2020, with only one prior case in the database from 2013 [Citation10].

While sodium nitrite is not a novel substance, its growing popularity as a means of suicide appears to be fueled by online suicide forums. Some of these forums contain explicit step-by-step instructions for completing suicide, including suggested doses, adjunctive medications (e.g. benzodiazepines and metoclopramide), and methods for acquiring sodium nitrite. In almost half of our patients, local poison center records specifically documented that patients researched this method of suicide on an online blog or forum. In addition, roughly half of the cases documented that the patient purchased the product online. Given its myriad of commercial uses, sodium nitrite remains easily accessible online and does not require specific licensing to purchase. The combination of readily accessible online information, detailed suicide instructions, and ease of product acquisition may contribute to the increase in cases observed over the final 2 years of this study period.

The diagnosis of sodium nitrite toxicity is often based on presenting symptoms and clinical signs of methemoglobinemia as the ingested product are not always known and serum concentrations are rarely available at the time of presentation. In this cohort, the majority of patients presented with tachycardia and cyanosis, as anticipated. Prior case reports have documented methemoglobinemia, even with accidental, and small ingestions of sodium nitrite [Citation3,Citation4]. The majority of patients in our cohort had a documented elevated methemoglobin concentration, with two patients’ methemoglobin concentrations above the limit of detection for the laboratory. These larger ingestions likely lead to higher methemoglobin concentrations.

A case report of a fatal sodium nitrite ingestion from 1990 indicated a lethal dose of 1 g [Citation7]. Most patients in this cohort ingested at least 15 g. Notably, one patient reportedly ingested 113 g and survived with aggressive treatment. These high doses likely explain our observed mortality rate of 41%. Importantly, the fatalities occurred despite maximal medical therapy including methylene blue administration and ACLS, highlighting the significant mortality associated with large sodium nitrite ingestions.

Large ingestions of sodium nitrite may not improve with traditional antidotes alone at typical dosing. Standard dosing of methylene blue is 1–2 mg/kg, with most patients responding to a single dose [Citation1]. Several patients in this cohort required repeat dosing, and one patient who survived received a total of 6 mg/kg. The maximum daily dosing is reported as 7 mg/kg due to the intrinsic oxidizing effects of methylene blue itself [Citation1]. Red blood cell transfusion was used in two patients in this cohort, but exchange transfusion, vitamin C (ascorbic acid), and vitamin E have also been proposed as possible treatments due to their anti-oxidant effects [Citation5]. While the data for these treatments is limited, they can be considered as adjuncts in the setting of large sodium nitrite ingestion with severe methemoglobinemia.

A similar NPDS study of sodium nitrite ingestions was also recently published, highlighting this new and rapidly growing trend [Citation11]. In this study, the NPDS database was queried between July 2015 and June 2020 for single substance sodium nitrite ingestions with the intent coded as suspected suicide. The initial search criteria yielded 47 patients, and 44 patients were included in the final cohort. While the database used and study period are similar to our study, the main methodologic difference lies in the review of the full case notes for each patient in the initial cohort to confirm accuracy of the coded NPDS data. The cohort size meeting the initial search criteria are similar in both our study (42 patients) and the aforementioned study (47 patients), with the difference of five patients best explained by their partial inclusion of cases from the year 2020, which was not included in our study period. However, the difference in final cohort size between the two studies is notable. McCann et al.’s final cohort size were 44 patients, excluding three patients who were lost to follow up, left against medical advice, and had minimal exposure not expected to cause clinical effects. Our study, by comparison, reviewed the non-coded free text notes for 35/42 of the initial cohort patients to confirm the accuracy of the coded data in NPDS. Ultimately, we excluded half of the initial cohort due to the incorrect product or intent of exposure, yielding a final cohort of 17 patients. By reviewing the free text case notes for each patient, we sought to ensure the accuracy of the reported data, as large datasets are often error-prone when isolated to small cohorts. The discrepancy between the final cohort size and mortality rates in the two studies, we believe, is thus explained by this methodologic difference. Additionally, by reviewing the case notes we were able to obtain additional clinical data for each patient, such as specific vital signs, antidote dosing, and additional details regarding intent and how the product was obtained. The conclusions of both McCann et al.’s study and ours are similar, highlighting this new and growing trend, and complement each other by confirming the persistence of this trend after confirming data accuracy.

Limitations

Despite the small cohort size (N = 17), this is the one the largest studies examining intentional sodium nitrite ingestions using a national database. We used a broad search strategy and confirmed the accuracy of the data in the NPDS database by reviewing the free text fields for each individual case, when available.

Nevertheless, there are several important limitations to the study. First, the retrospective design relies on the integrity of a national database including accuracy of coding by poison center specialists. We sought to minimize coding errors by reviewing each poison center’s free text fields to confirm exposure details. However, we did not receive records for seven cases, resulting in a potential failure to confirm the exposure and patient data. Coding errors could also have resulted in a failure to detect patients in the NPDS database, and in many instances the clinical data available in the NPDS database and poison center free text fields was incomplete, resulting in an underreporting and incomplete characterization of cases. Second, all poison center-based studies are affected by reporting bias. The NPDS relies on voluntary reporting of poisonings to PCCs. Therefore, patients managed without PCC involvement are not represented here. Finally, we were unable to confirm exposure with serum sodium nitrite concentrations, as there is not a routine laboratory assay or other standardized method for measuring it outside of the research setting. However, the history, clinical presentation, and response to treatment were highly suggestive of exposure.

Conclusion

In this 11-year retrospective review of intentional sodium nitrite ingestions reported to the NPDS, we identified a novel and growing trend in suicide means with all identified patients presenting in the final two years of the study period. As suicide websites and forums expand, sodium nitrite toxicity, with its significant morbidity and mortality, will likely be more frequently encountered by clinicians and poison control centers. As regulatory changes are unlikely to be forthcoming, clinicians should have a high index of suspicion for sodium nitrite ingestion in cases of severe methemoglobinemia and be prepared for aggressive treatment.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the following poison control centers for contributing to this study (Florida Poison Information Center Tampa, Florida Poison Information Center Miami, Florida/US Virgin Islands Poison Information Center Jacksonville, National Capital Poison Center, West Texas Regional Poison Center, Southeast Texas Poison Center, Children’s Hospital of Michigan Regional Poison Control Center, Washington Poison Center, Philadelphia Poison Control Center, Upstate New York Poison Center, Georgia Poison Center, Regional Center for Poison Control and Prevention Serving Massachusetts and Rhode Island, Banner Poison Control Center, Connecticut Poison Control Center, Oregon Poison Center, Rocky Mountain Poison and Drug Center, Nebraska Regional Poison Center, Missouri Regional Poison Center, Wisconsin Poison Center, Oklahoma Poison Control Center).

Disclosure statement

No financial associations or conflicts of interest. Presented at the American College of Medical Toxicology Annual Scientific Meeting 16 April 2021.

References

- Price DP. Methemoglobin inducers. In: Nelson LS, Howland MA, Lewin NA, Smith SW, Goldfrank LR, Hoffman RS, editors. Goldfrank’s toxicologic emergencies. New York (NY): McGraw-Hill Education; 2019. p. 1703–1712.

- Joosen D, Stolk L, Henry R. A non-fatal intoxication with a high-dose sodium nitrate. BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014:bcr2014204825.

- Maric P, Ali SS, Heron LG, et al. Methaemoglobinaemia following ingestion of a commonly available food additive. Med J Aust. 2008;188(3):156–158.

- Gautami S, Rao RN, Raghuram TC, et al. Accidental acute fatal sodium nitrite poisoning. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1995;33(2):131–133.

- Harvey M, Cave G, Chanwai G. Fatal methaemoglobinaemia induced by self-poisoning with sodium nitrite. Emerg Med Australas. 2010;22(5):463–465.

- Katabami K, Hayakawa M, Gando S. Severe methemoglobinemia due to sodium nitrite poisoning. Case Rep Emerg Med. 2016;2016:9013816.

- Gowans WJ. Fatal methaemoglobinaemia in a dental nurse. A case of sodium nitrite poisoning. Br J Gen Pract. 1990;40(340):470–471.

- Mudan A, Repplinger D, Lebin J, et al. Severe methemoglobinemia and death from intentional sodium nitrite Ingestions. J Emerg Med. 2020;59(3):e85–e88.

- Micromedix poisindex system (IBM Micromedex healthcare series [Internet database]. Greenwood Village (CO): IBM Watson Health. 2020.

- Vodovar D, Tournoud C, Boltz P, et al. Severe intentional sodium nitrite poisoning is also being seen in France. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2021;1–2.

- McCann SD, Tweet MS, Wahl MS. Rising incidence and high mortality in intentional sodium nitrite exposures reported to US poison centers. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2021;1–6.