Abstract

Background

Cannabis is a schedule 1 substance that cannot be possessed within the United States according to federal law. On March 31 2021, New York State legalized cannabis for sale and consumption. This study assesses the safety labeling and packaging aimed at children of cannabis containers during the peri-legalization period in New York City.

Methods

This is a cross-sectional and descriptive comparative study in which sidewalks in New York City were inspected for labeled cannabis containers during the four months prior and four months post legalization, i.e. from December 2020 until July 2021. Packages were systematically analyzed using a scoring system based on advertising techniques that may appeal to children and the American College of Medical Toxicology’s (ACMT) recommendations on cannabis safety labeling.

Results and DiscussionOf the 114 packages, none met ACMT’s recommended safety labeling guidelines. Only 52% of containers indicated their contents, 40% referenced food, and 85% included elements that may appeal to children.

Conclusion

Precautionary measures such as child-resistant packaging, warning labels, and avoiding marketing to children are uncommon. Policy makers should consider regulating the safety labeling and advertising which appeals to children on cannabis packaging.

Keywords:

Background

Cannabis is a schedule 1 substance that cannot be possessed within the United States according to federal law. As of June 2022, 19 states including Oregon, Colorado, and California have legalized recreational cannabis within their own borders [Citation1]. Since the Obama administration released the Cole Memorandum in 2013, federal authorities generally do not prosecute intrastate cannabis commerce [Citation2]. This is similar to the Dutch policy gedoogbeleid in which cannabis is explicitly illegal, but tolerated by enforcement policy [Citation3]. States where cannabis is legal prohibit purchase by minors and mandate regulation of packaging labels, such as California’s “EXTREME CAUTION” warning [Citation4]. There are no federally mandated requirements for cannabis labeling, however the American College of Medical Toxicology (ACMT) has released a position statement addressing best practices to safeguard children from unintentional cannabis exposure [Citation5].

Cannabis contains the psychoactive substance delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), which is used recreationally for its intoxicating effects. It may be smoked, vaporized and inhaled, or infused into foodstuffs and ingested in the form of “edibles.” Prior to the 1960s the THC content of cannabis was approximately 2%, however the expansion of the cannabis industry has led to increasing THC potency due to breeding and hybridization. Today, many strains of American cannabis contain in excess of 28% THC [Citation6]. Frequent recreational use of high potency THC is associated with addiction and psychosis [Citation6, Citation7]. Despite risks associated with high dose THC, quantification of THC dose on cannabis product labels is often inaccurate [Citation8].

In October 2018, Canada legalized recreational cannabis use. This led to a significant increase in rates of pediatric ICU admissions, children with respiratory involvement or altered mental status, and children younger than 12 being exposed [Citation9]. In the USA, states where cannabis is legalized see increased rates of unintentional pediatric cannabis exposure [Citation10–13]. These “unintended consequences” of cannabis legalization on the pediatric population may be influenced by safety labeling and advertising [Citation14]. Product labeling helps consumers understand the risks and intended use of products, and deters unintentional youth access [Citation15].

In states where cannabis is illegal, package labeling is unregulated and designed at the discretion of distributors. On March 31 2021, New York State legalized cannabis for sale and consumption [Citation16]. Cannabis in New York City is typically sold from person to person via delivery services, indoor sales, street-level sales, and unofficial storefronts such as newsstands [Citation17]. New York City is the largest American city with a municipal population of 8.8 million and over 20 million in the metropolitan area [Citation18]. Now that New York has legalized cannabis, the state will likely regulate and standardize packaging requirements as has been done in states such as Oregon and California. This study assesses various cannabis package labels during the peri-legalization period in New York City, and to characterize the extent to which cannabis packaging can fail to meet reasonable standards for protecting children and adolescents.

Methods

This is a descriptive and cross-sectional study in which sidewalks in Manhattan in New York City were inspected for discarded packaging materials suspected to be cannabis containers. The collection of these containers is similar to prior studies sampling discarded cigarette butts used to estimate environmental hazards [Citation19–21]. During the study period the principal investigator surveilled a convenience sample of sidewalks totaling 716.5 kilometers in length. All detritus was actively assessed for study inclusion. Packages found during the 4-month pre-legalization period (December 2020 - April 2021) were compared to packages found during the 4-month post-legalization period (May 2021 – July 2021) from the same neighborhoods.

Re-sealable plastic envelopes and containers that included text or graphic elements were screened for study. Packages were not assessed if they contained no textual or pictographic design (e.g. unlabeled zip-top bags), or if they were a commercial non-drug product (e.g. potato chips unrelated to cannabis). Packages were included for study if they contained any one or more of the following:

Text indicating cannabis (e.g., “marijuana, cannabis, THC, kush, OG,” or other indicators of cannabis as specified by the 2018 DEA intelligence report on code terms for drugs) [Citation22].

Images indicating cannabis (e.g., a depiction of the characteristic leaf).

Odor of cannabis as assessed by a board-certified medical toxicologist.

Each package was digitized with a global-positioning-system (GPS) enabled camera and systematically analyzed; data was abstracted into an a-priori standardized collection instrument created for this study (summarized in ). Data abstraction was based on 1) adherence to ACMT’s guidelines on safety labeling and 2) marketing elements which may appeal to children.

Table 1. Analysis of cannabis package labels regarding safety and marketing.

Packages containing botanical materials were assigned a score out of 4 and edibles a score out of 5 based on whether or not they met ACMT’s recommendations for labeling. Four out of the five criteria are assessed objectively (i.e. a warning label and hazard pictogram are either present or absent), whereas one criterion (prohibition of appealing to children) was based on a review of packaging that appeals to children [Citation23]; i.e. the criterion was construed to mean absence of cartoons, reference to sweets or other foods that appeal to children, reference to national symbols (e.g. Major League Baseball team iconography), and multiple colors. Packages were additionally scored on advertising characteristics such as presence of cartoonish design, hand-written text, depiction of sweet food, and invocation of national trademarks (e.g. “Rick and Morty” or “The New York Yankees”). A t-test was performed on each score criterion to assess for statistically significant differences.

This study does not evaluate human subjects or biospecimens, and is therefore exempt from internal review board assessment.

Results

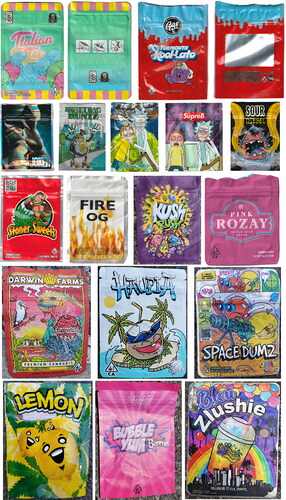

A total of 114 packages were included and their labels underwent data abstraction and thematic assessment. Text and/or characteristic cannabis leaf images were used to identify 87% (n = 99) of packages as cannabis containers, whereas odor alone was used for 13% (n = 15) of packages. Example packages are depicted in . There were 31 packages found during the pre-legalization and 83 during the post-legalization period. The results are summarized in .

Figure 1. Sample cannabis packages. Samples include resealable packaging, cartoons, references to food.

Out of 114 packages none met all of ACMT’s guidelines for safety labeling. Fewer than 50% (n = 55) contained a hazard pictogram and warning statement, 10% (n = 11) were child-resistant, none included emergency poison contact information, and 85% (n = 103) included elements that appeal to children.

Over 85% (n = 103) of the packages contained one or more features which may appeal to children. Cartoon characters were present in 38% (n = 43) of samples, 31% (n = 35) depicted a nationally recognized brand, and 36% (n = 41) depicted food appealing to children. Prior to legalization 58% (n = 18) of packages contained two or more bright colors, versus 83% (n = 69) after legalization, which was statistically significant (p = 0.002). 54% (n = 62) of packages were labeled as originating from California.

During the post-legalization period 5/83 (6%) of the packages were edible THC products rather than botanicals (leaf and/or bud), compared to 0/33 (none) from the pre-legalization period. Five out of five of these packages received a score of 1/5 based on ACMT’s criteria for safety labeling. The edibles packages are depicted in .

Limitations

This is not an exhaustive study of cannabis package labeling. This study only examined packages that included a label, and a significant portion of cannabis is sold in unlabeled containers. Limitations include sampling of urban outdoor detritus (which may bias towards outdoor cannabis use rather than that used in a private home), unconfirmed substance origin, uncertain time of packaging in relation to the study period, absence of laboratory THC confirmation, and lack of laboratory assessment for adulterants or alternatives such as synthetic cannabinoids. Although all detritus on the sidewalks was evaluated for study inclusion, the sidewalks themselves were not randomized and favored the following NYC neighborhoods: Washington Heights, Downtown, and Midtown. Previous studies have demonstrated that olfactory assessment may indicate the presence of cannabis [Citation24–26], however it does not rule out adulterants. A larger number of packages was found during the post-legalization period, however this may be confounded by increased outdoor activity due to relaxed restrictions of the COVID-19 pandemic and warmer weather.

Discussion

The packaging materials in this study were collected and analyzed during a new period of cannabis’s legal status in New York State wherein sale, advertising, policy, manufacture, and distribution are expected to be in flux. Many of the labels lacked warnings, safety information, addressment of child exposure, or even contents. The legalization of cannabis in New York is a potential opportunity to minimize certain risks by enforcing regulation of packaging and advertisement. Public health objectives should be addressed including minimizing youth’s access to drugs, intoxicated driving, addiction, substance adulteration and contamination, and concomitant use of cannabis with other intoxicating substances [Citation27].

In 2014 Oregon became one of four states which legalized retail recreational cannabis. From 2015 − 2016 more than half of adults and adolescents reported seeing or hearing advertisements for retail cannabis in the previous 30 days [Citation28]. In New York State, as in other states where cannabis is newly legalized, there is expected to be an increase in market promotion and commerce. Studies of tobacco and alcohol demonstrate advertisements increase consumption among adults, adolescents, and children [Citation29, Citation30]. Businesses which sell cannabis already use marketing strategies with youth appeal [Citation31]. Cannabis marketing to youths, particularly branding, is associated with cannabis use disorder in teenagers [Citation31]. The packaging styles described in this study may persist as advertisements even as regulation increases.

Many of the packages discovered in this study simultaneously lacked safety labeling and incorporated design elements which appeal to children. Particularly concerning are packages of high dose THC-containing candy. Based on the label, these sweets are visually indistinguishable from their non-intoxicating counterparts and contain dangerously high doses of THC. Many of the packages are labeled to contain in excess of 500 mg THC, which is 100 times the maximum serving size and 10 times the limit for a package in certain states [Citation14]. Medically significant pediatric cannabis toxicity has been reported with THC doses as low as 15 mg [Citation32]. Since 2017, the rate of pediatric exposure to edibles has increased with 16.8% developing moderate or severe medical effects [Citation13]. Excessively potent and improperly labeled THC-infused edibles are an international problem [Citation33].

As cannabis becomes more commonly available, unintentional ingestions and toxicity are expected to rise. After Colorado legalized cannabis there was a significant rise in unintentional pediatric exposures compared to national rates, with similar patterns in other states that legalized marijuana [Citation10, Citation12]. From 2016 − 2017 the poison center of Oregon and Alaska was consulted on 253 symptomatic individuals who were acutely exposed to cannabis, 28% of whom were children under the age of twelve [Citation32]. Typical pediatric symptoms were neuroexcitation with occasional major adverse outcomes [Citation32].

At the time of collection, the packages in this study contained federally illegal material; many labels disregarded regulations about a potentially harmful material. Fewer than 10% were constructed to be child-resistant. The Poison Prevention Packaging Act of 1970 stipulates that child-resistant packaging must be at least 80% effective [Citation34]. The introduction of child-resistant containers is attributed to have prevented thousands of pediatric deaths and non-fatal injuries since 1970 [Citation35, Citation36]. Though cannabis is not thought to be nearly as dangerous as opioids and cocaine, as states legalize retail cannabis commerce there should be child-resistant packaging safety regulation. Additionally, public health campaigns should include messages which encourage adults to store cannabis in locked out-of-reach containers [Citation37]. Unlabeled cannabis containers, i.e. clear plastic “dime bags,” lack both safety labels and marketing elements. All of the labeled packages in this study lacked adequate safety labeling, however 85% included elements that appeal to children and adolescents.

Conclusion

During the period around cannabis legalization in New York State, cannabis packaging may include advertising that appeals to children, omit safety warnings, and lack child resistance. Zero out of 114 packages met all of ACMT’s guidelines for safety labeling. In order to safeguard children and public health, policymakers should ensure that all cannabis is labeled with appropriate safety warnings and marketing practices that do not appeal to children.

Abbreviations

Delta-9-Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) American College of Medical Toxicology (ACMT)

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Funding

The author(s) reported there is no funding associated with the work featured in this article.

References

- State Medical Cannabis Laws. Accessed June 24, 2022. Available from: https://www.ncsl.org/research/health/state-medical-marijuana-laws.aspx.

- Cole J. Memorandum for all United States attorneys: guidance regarding federal marijuana enforcement; 2013. Available from: https://www.justice.gov/iso/opa/resources/3052013829132756857467.pdf.

- Toleration policy regarding soft drugs and coffee shops | Drugs | Government.nl. Accessed April 23, 2021. Available from: https://www.government.nl/topics/drugs/toleration-policy-regarding-soft-drugs-and-coffee-shops.

- California. Manufactured Cannabis Safety; 2018. 111. Available from: https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/CEH/DFDCS/MCSB/CDPHDocumentLibrary/DPH-17-010.pdf.

- Amirshahi MM, Moss MJ, Smith SW, et al. ACMT position statement: addressing pediatric cannabis exposure. J Med Toxicol. 2019;15(3):212–214.

- Stuyt E. The problem with the current high potency THC marijuana from the perspective of an addiction psychiatrist. Mo Med. 2018;115(6):482–486. /pmc/articles/PMC6312155/

- Di Forti M, Arianna M, Carra E, et al. Proportion of patients in South London with first-episode psychosis attributable to use of high potency cannabis: a case-control study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(3):233–238.

- Vandrey R, Raber JC, Raber ME, et al. Cannabinoid dose and label accuracy in edible medical cannabis products. JAMA. 2015;313(24):2491–2493.

- Cohen N, Galvis Blanco L, Davis A, et al. Pediatric cannabis intoxication trends in the pre and post-legalization era. Clin Toxicol. 2021.

- Wang GS, Le Lait MC, Deakyne SJ, et al. Unintentional pediatric exposures to marijuana in Colorado, 2009-2015. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(9):e160971.

- I Claudet MBCBNF. A 10-year review of cannabis exposure in children under 3-years of age: do we need a more global approach? Eur J Pediatr. 2017;176(4):553–556.

- Wang GS, Roosevelt G, Le Lait MC, et al. Association of unintentional pediatric exposures with decriminalization of marijuana in the United States. Ann Emerg Med. 2014;63(6):684–689.

- Whitehill JM, Dilley JA, Brooks-Russell A, et al. Edible cannabis exposures among children: 2017–2019. Pediatrics. 2021;147(4):e2020019893.

- Wang GS. Pediatric concerns due to expanded cannabis use: unintended consequences of legalization. J Med Toxicol. 2017;13(1):99–105.

- Sontag JM, Wackowski OA, Hammond D. Baseline assessment of noticing e-cigarette health warnings among youth and young adults in the United States, Canada and England, and associations with harm perceptions, nicotine awareness and warning recall. Prev Med Reports. 2019;16:100966.

- New York. Marihuana Regulation and Taxation Act; 2021. Available from: https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/bills/2021/S854.

- Sifaneck SJ, Ream GL, Johnson BD, et al. Retail marijuana purchases in designer and commercial markets in New York city: sales units, weights, and prices per gram. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;90(SUPPL. 1):S40–S51.

- U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: New York city, New York. Published 2021. Available from: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/newyorkcitynewyork.

- Qamar W, Abdelgalil AA, Aljarboa S, et al. Cigarette waste: assessment of hazard to the environment and health in Riyadh city. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2020;27(5):1380–1383.

- Torkashvand J, Godini K, Jafari AJ, et al. Assessment of littered cigarette butt in urban environment, using of new cigarette butt pollution index (CBPI). Sci Total Environ. 2021:769.

- Valiente R, Escobar F, Pearce J, et al. Estimating and mapping cigarette butt littering in urban environments: a GIS approach. Environ Res. 2020;183:109142.

- Slang terms and code words: a reference for law enforcement personnel DEA intelligence brief DEA intelligence report. Published online 2018.

- Elliott C, Truman E. The power of packaging: a scoping review and assessment of child-targeted food packaging. Nutrients. 2020;12(4):958.

- Rice S, Koziel JA. The relationship between chemical concentration and odor activity value explains the inconsistency in making a comprehensive surrogate scent training tool representative of illicit drugs. Forensic Sci Int. 2015;257:257–270.

- Rice S, Koziel JA. Characterizing the smell of marijuana by odor impact of volatile compounds: an application of simultaneous chemical and sensory analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(12):e0144160.

- Doty RL, Wudarski T, Marshall DA, et al. Marijuana odor perception: studies modeled from probable cause cases. Law Hum Behav. 2004;28(2):223–233.

- Pacula RL, Kilmer B, Wagenaar AC, et al. Developing public health regulations for marijuana: lessons from alcohol and tobacco. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(6):1021–1028.

- Fiala SC, Dilley JA, Firth CL, et al. Exposure to marijuana marketing after legalization of retail sales: Oregonians’ experiences, 2015–2016. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(1):120–127.

- DiFranza JR, Wellman RJ, Sargent JD, et al. Tobacco promotion and the initiation of tobacco use: assessing the evidence for causality. Pediatrics. 2006;117(6):e1237–e1248.

- Noel JK, Sammartino CJ, Rosenthal SR. Exposure to digital alcohol marketing and alcohol use: a systematic review. J Stud Alcohol Drugs Suppl. 2020;19(s19):57–67.

- Trangenstein PJ, Whitehill JM, Jenkins MC, et al. Cannabis marketing and problematic cannabis use among adolescents. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2021.82.288. 2021. 82(2):288–296.

- Noble MJ, Hedberg K, Hendrickson RG. Acute cannabis toxicity. Clin Toxicol. 2019;57(8):735–742.

- Lindsay CM, Abel WD, Jones-Edwards EE, et al. Form and content of jamaican cannabis edibles. J Cannabis Res. 2021;3(1):29.

- Poison Prevention Packaging Act of 1970; 1970:10. Available from: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CFR-2013-title16-vol2/xml/CFR-2013-title16-vol2-chapII-subchapE.xml.

- Rodgers GB. The safety effects of child-resistant packaging for oral prescription drugs. JAMA. 1996;275(21):1661–1665.

- Budnitz DS, Lovegrove MC. The last mile: taking the final steps in preventing pediatric pharmaceutical poisonings. J Pediatr. 2012;160(2):190–192.

- Brooks-Russell A, Hall K, Peterson A, et al. Cannabis in homes with children: use and storage practices in a legalised state. Inj Prev. 2020;26(1):89–92. injuryprev-