Abstract

A health communication project, to develop information to support families caring for people with dementia, is described. Close collaboration of designers with carers – ‘experts by experience’ – and clinicians and other professionals – ‘experts by training’ – was used. Carer consultation led to a printed (rather than digital) handbook. An iterative process of carer and clinician consultation and design shaped the material form of the handbook. Carers’ needs for different kinds of information were met by a modular approach and tailored module design. Evaluation following distribution of the handbook suggested it improved carers’ understanding of dementia significantly compared to the information from diverse sources supplied previously. It did not, however, influence people’s confidence in their ability to care, which appeared to be supported better through carer education courses. The specific contribution of information design and its potential for delivering return on investment are discussed.

Introduction

The benefits of information for patients and their carers about managing health conditions have been widely recognized (Coulter and Ellins Citation2007), in part because of a shift towards a partnership (patient and clinician) approach to healthcare (Bridges, Loukanova, and Carrera Citation2008). Information provision through spoken exchanges is an essential part of patient care and enables personalization, and response to questions (Ong et al. Citation1995) but spoken exchanges may be time-limited and at fixed points, creating a need for information access outside care settings. Additionally, with a progressive, neurodegenerative condition, such as dementia,1 many people will have prominent problems with recall of information, which limits the usefulness of spoken advice given directly to them. As dementia advances, people lose their ability to look after themselves and to make informed decisions, placing a burden on family members, who eventually might have to look after them and make surrogate decisions for them. Family members (spouses, children and other relatives), without professional experience, need information to understand the condition (Newbronner et al. Citation2013).

In this context, our research team was approached by a local Mental Healthcare Trust (administrative organization for care delivery within a UK region)2 to co-develop carer-focused information. The approach followed demands by carer representatives for better quality information than was being provided.

In this article, we describe our response: a co-design collaboration that is ‘designers and people not trained in design working together in the design development process’ (Sanders and Stappers Citation2008). Our goal was to develop a post-diagnosis information pack that put carers’ needs at its core. In responding to carer needs we developed a print manual, contrary to the trend to make information accessible via web resources.

Research context

The need for information to educate and support non-professionals caring for people with dementia has been well documented in the dementia care literature (Chang et al. Citation2010; Stajduhar et al. Citation2011; Wackerbarth and Johnson Citation2002; Wald et al. Citation2003), with some studies isolating specific communication gaps among professionals, patients and carers (Forbes, Bern-Klug, and Gessert Citation2000; Fried et al. Citation2011; Keller et al. Citation2008; Stokes, Combes, and Stokes Citation2015). A systematic review concluded that providing information for carers can reduce patients’ neuropsychiatric symptoms and improve their quality of life (Corbett et al. Citation2012). Opinion on how information should be provided has been divided as follows:

that information should be paced, with limited information at diagnosis and, subsequently, at each interaction between professionals and carer as a patient’s condition progresses (Wald et al. Citation2003).

that comprehensive information from diagnosis facilitates discussion between patient and carer so they can prepare for the carer to assume decision-making responsibility (Chang et al. Citation2010; Ducharme et al. Citation2011, Mastwyk et al. Citation2014).

Existing studies include consultation with carers on topics to be covered (Wald et al. Citation2003), to evaluate professionally developed information (Chang et al. Citation2010), and to assess the readability of materials (Weih et al. Citation2008), but have not followed a full, user-centred process (involving users and stakeholders). The transfer of much public information from paper to the web has precipitated investigation of web site provision (Anderson, Nikzad-Terhune, and Gaugler Citation2009; Bouchier and Bath Citation2003). However, prior to our research, there was evidence for a preference for printed information among carers (Jackson et al. Citation2011: Wald et al. Citation2003).

As the preceding paragraphs suggest, research literature in dementia care focuses on the content delivered to carers but not on communication design for this delivery. This may be due to lack of awareness of the opportunity to ensure information is designed to meet users’ needs (Hartley Citation2012), and of the potential of design, and its social and genre framed conventions, to signal relevance, access, and meaning (Kostelnick Citation2017). Tsekleves and Cooper (Citation2017, 395–396) have demonstrated that health communication is a significant theme in current research in design for health, with a broad scope. Projects aimed at supporting service users directly through information design include, for example: the Design Council/PearsonLloyd National Health Service (NHS) collaboration, A Better A&E,3 to reduce aggression by informing patients about A&E processes; collaboration of designers, clinicians, parents and children to develop tools to support young patient and parent decision-making (Zender, Brinkman, and Widdice Citation2017); the body of research to address communication of medicines information to patients (Van der Waarde Citation2010); recent collaborations among designers, architects and pharmacists to develop interventions in pharmacies to increase public understanding of antimicrobial resistance (Walker et al. Citation2018).

Despite the impact of initiatives such as those described above, the effectiveness of partnership working between health service providers, designers and service users may not yet be understood generally. The many meanings of the word ‘design’, and for some its association with decoration (Walker Citation2017), and the differing status of clinical and design professionals (Zender, Brinkman, and Widdice Citation2017) may contribute to poor understanding of design’s strategic and functional potential; it may inhibit, particularly, the early engagement between service providers, users and designers which underscored the projects above, and which we were able to build into the project reported here.

Initial scoping consultation with carers and professionals

In order to understand carers’ current experience of receiving information, six semi-structured, group discussions were conducted with 26 family carers (siblings, spouses, and children of people with dementia) attending carer education courses run by the Healthcare Trust. This sample ranged in age from over 50 to over 80; they had relatives with diagnoses of different types and at different stages of dementia. As attendees at a carer education course, they were, of course, already engaged with improving their ability to care, representing only a subsection of the carer community.

Three complementary group interviews were conducted with 18 dementia care professionals (psychiatrists, community psychiatric nurses, clinical psychologists, occupational therapists, speech and language therapists and dementia support professionals).

The interviews were recorded, with participants’ permission, and transcribed, then analyzed thematically. Key themes from this analysis are outlined below.4

Current information provision lacked focus

The consensus among carers and professionals was that diagnosis, or shortly after, was the best opportunity to present information. Professionals referred to the Trust’s weekly programme to build carers’ knowledge through education courses. However, only a minority of carers were able to attend those courses. Post-diagnosis and carer course information was presented in several different formats, including desktop-published notes prepared by clinic staff, booklets from specialist organizations, and factsheets, printed from the website of national dementia charity, The Alzheimer’s Society. It appeared that while the information itself may have been high quality, its delivery made it difficult for carers to use, as illustrated in one interview exchange:

Carer: ‘I keep it all in a big carrier bag at the back of the wardrobe’

Researcher: ‘And have you used it?’

Carer: ‘No’

(Husband, 78, caring for wife)

Carers needed information to consult outside clinic appointments

Professionals reported that even though they preferred to provide information through direct discussion, details given to patients and carers were often misunderstood or forgotten, requiring repetition. They saw ‘take away’ information as necessary reinforcement to spoken advice.

Printed information

The differing trajectories of dementia, even for people with the same diagnosis, might have indicated a comprehensive, digital resource that could be accessed selectively. Some carers reported using online information sources successfully but many, particularly older carers, did not use digital media or felt they did not have the time or skills to search for information effectively. These carers said they wanted printed, ‘browsable’ information.

From the NHS (UK National Health Service)

Carers’ accounts of unsuccessful web searches included accessing information they subsequently found irrelevant (sometimes from other countries) or from organizations that they did not trust (believing them to be commercially motivated). They trusted the information provided by the Trust, anticipating a quality-assured guide, from ‘our NHS’.

Appropriate and appealing for a range of expertise

When asked whether they had shared information they received with friends or relatives, carers said they thought others would not be interested, and that the information was not presented in a manner that was appropriate for someone without a direct interest in it. Professionals reported a range of aptitude and preparedness to care among families, highlighting difficulties for male carers who had previously taken very specific roles in the practicalities of domestic life.

Clarifying and signposting to local support services

Professionals reported a pressing carer need for signposting to sources of practical help. Carers also noted the difficulty of understanding and navigating medical and social services, and charitable agencies that provided care and funding. Some dementia care support is organized nationally, but not all national agencies provide support in all regions. Carers wanted to know which agencies were active locally.

Difficult topics

Opinion was divided on the inclusion of topics that could cause distress; for example, relating to disinhibited behaviours, or incontinence, or preparation for end of life. Most carers and professionals, however, felt that carers should be supported to find information they needed. The word ‘dementia’, while misunderstood and feared by many, has been increasingly accepted in recent years. Some carers said they resisted using it in order not to distress the person they cared for. An unexpected sensitivity for some carers was the term ‘carer’ when they still wanted to be thought of in their family relationship, husband, daughter, etc.

In summary: directions for design

There were parallels in several issues raised in carer and professional interviews. The interviews covered, to some extent, what would be communicated to carers; they were useful also in their insights into how information could be used by carers

with different levels of understanding and preparedness

to help them understand and respond to wide-ranging and changing symptoms

as support for those who could not attend courses

as back up to direct discussion with professionals

for advice when clinical support was not available

to signpost sources of support for patient and carer.

While the consultation suggested a printed guide, this would be wasted without a focus on creating ease of access to the large amount of information carers needed – from the guide’s three-dimensional format to the detail of its language.

Responding through design

Prototyping and consultation on information format

Initial physical prototypes

In a traditional publishing model, seen in existing studies, professionals and writers create content, which a designer then packages into a formatted publication for distribution. We reversed this process, using the carer and professional consultations as a basis for developing physical prototypes of potential guides, with indications of content type. We presented the prototypes in discussions with further groups of carers and professionals, for them to handle and reflect on how they would use them in their home setting.

Conscious of the difficulty non-designers have in reflecting on aspects of design (Black and Stanbridge Citation2012) and the long-established difference between people’s perceptions of and actual differences in materials (Nelson and Smith Citation1990) and between envisaged and actual use (Black et al. Citation2013), we concentrated on people’s first impressions of the prototypes. We aimed to tease out factors that would persuade potential users that the information was designed for their needs (Moys Citation2014), to reduce the likelihood of their consigning it to their equivalent of ‘the back of the wardrobe’.

Materials used

Prototypes for a modular set of information booklets, bound either in a ring binder or box file, were prepared. A bound, single volume was considered but a modular approach was used to reduce the impression of an overwhelming amount of information, and to create flexibility for carers to include additional, relevant information. We presented both A4 and A5 formats as we could see benefits and disadvantages for both. Examples of the booklet prototypes used are shown in .

Figure 1. Prototypes used as stimuli in carer and professional consultations; left, samples of the prototype A4 and A5 booklets, showing parallel page formats for discursive texts; right, prototypes for a dementia services directory, record keeping forms booklet and A–Z of symptoms and behaviours.

We prototyped examples of content presentation that we believed would address issues raised in the initial scoping discussions.

A sample directory of dementia services across the region.

Record keeping forms for carers and professionals to track issues raised by patients and carers, and the advice given by professionals.

Pages showing an A–Z of symptoms and behaviours, including topics that carers might find difficult to discuss, such as incontinence and sex, alongside less controversial topics, such as attention span.

Discursive information in structured text.

Procedure

Eight small group discussions were held, with participants drawn from carers attending carer education courses and local social groups for people with dementia and their carers (72 people, ages ranging from over 40 to over 70, were consulted; none had been involved in the initial scoping study). Local social groups were included to extend feedback beyond participants in carer education courses. We also gathered feedback on the prototypes from the professionals who had contributed to the initial scoping.

Feedback

Feedback to our approach was broadly positive

According to one carer ‘…long overdue and desperately needed,’ and to another ‘good to have this information all in one place’.

Physical form

There was a slight preference for ring binders which were seen as more organized than box files. When asked if they had hole punches (to be able to add further materials to a binder) most participants responded positively (we acknowledge this sample may not have been representative).

Size

A5 was thought to be more discreet than A4 (a positive quality for both carers and professionals, keen to ensure information was used rather than consigned out of sight). However, the potential thickness of an A5 ring binder or box file, caused concern: the A5 sample pages had a single text column to maintain a legible type size in the page width, whereas the A4 format could accommodate a double column with potential for more efficient information presentation (see sample page formats in , left).

Navigation cues

The prototype demonstrated the use of colour coding, contents listing and cross-referencing to support information navigation. In discussing the presentation of information in separate, linked booklets, participants highlighted the need for booklets to stand alone, with limited cross-referencing. Participants also commented on the incidental effect of using different colours (and text format), according to booklet content, apparently making the pack as a whole more approachable, ‘less like a manual’, than had all booklets been bound together or repeated the same format.

Content

Although not the main purpose of this consultation, the proposed booklet topics were thought to reflect content carers would need. Response to the guide to care services was particularly enthusiastic; according to one carer ‘this breaks down the glass wall between us and them’. The usefulness of the A–Z of symptoms and behaviours was highlighted with no comments about the range of symptoms illustrated (although expressing concerns may have been awkward in the group setting).

Language

While detailed assessment of the language was not possible in this exercise, participants commented that sample texts appeared easy to read. They discussed the difficulty of interpreting terms and abbreviations used in doctors’ letters; similarly their difficulty remembering the names or purpose of prescribed medicines.

Naming the handbook

As with the scoping groups, carers were sensitive about the words ‘dementia’ and ‘carer’. Professionals felt the term ‘dementia’ was current and should be used. There was less consensus on the word ‘carer’ but an inclusive alternative could not be agreed.

Pictures

Some prototypes were shown with sample pictures. Participants thought that, even if not informative, pictures would relieve the most discursive text and cue the location of information they had read previously. Carers were concerned that pictures should not present unrealistically positive perspectives on dementia and dementia care.

In summary: directions for design

The feedback gave some steer on the future form for information presentation. We followed the preference for a ring-bound manual. We used the A4 format, which gave more flexibility for formatting information. A4 was also compatible with most documents provided by the NHS (Black et al. Citation2013). In the ensuing process of refining the design and preparing content, we took in carers’ points about keeping the booklets self-contained, providing definitions of medical terms and giving information about medication. We extended the A–Z guide into a separate booklet. Issues of terminology for ‘dementia’ and ‘carer’ remained intractable and were revisited during subsequent consultations.

Iterative content and design development

Throughout detailed development, we sought advice and feedback from two carer advocates (both former carers), and professionals within the Trust with expertise specific to the sections of the handbook.

Content

We gathered a corpus of relevant information from previous publications, and liaised with our carer and professional advisors, from which we wrote copy for the component booklets of the guide. The level of detail that could be included was limited, so we identified sources of further information to be signposted from the guide. In doing so we aimed to allay carers’ concern about the authority of external sources.

We followed principles of accessible writing: writing in short paragraphs with a clear heading structure, writing in the active voice, addressing the reader directly (‘you’) and avoiding jargon but defining technical terms where needed. We aimed to reduce the amount of discursive text by use of bulleted lists, checklists, and tables.

Iterative reviewing by carers and professionals yielded suggestions for amendments, for additional content or signposts to further sources. We edited as we wrote, aiming to keep document length approachable, and also ensure production within a constrained budget.

Document design

The design approach (a two-column A4 page)5 signalled in the initial prototypes was formalized into a detailed specification for the different content types. We needed to ensure that accessibility and ease of reading were not compromised by text typography, or by over-complex presentation. Across all booklets, a consistent approach was required for elements such as bulleted lists, tables, highlighted examples, pictures, etc.

Samples of designed document pages were sent to carers and professionals for feedback. Our respondents were confident about legibility and navigation. Their main concern was to limit ‘text-dense’ pages, as had been discussed in feedback to our first prototypes. Therefore, as well as including pictures and other graphically distinct elements, we added narrative case studies, differentiated graphically, to illustrate carers problem solving with professional input (see ).

Non-narrative elements

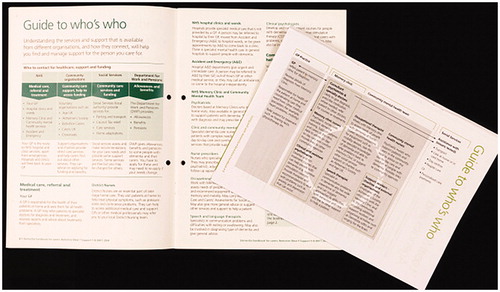

Some document elements, although anticipated in the earliest prototypes, went through many iterations; for example, a diagrammatic guide to the services available to support care. This changed significantly from the initial prototypes, where we anticipated using it to demonstrate patient flow between services (). The flow approach was abandoned as our coverage of services developed and it was found to distract from information about the services themselves. Our final approach was a simple, column-based representation, positioned so that readers could see both the service structure and details of individual services on a double page spread.

Figure 3. Diagramming the different sources of dementia care; an initial attempt to show the different sources of dementia care support and patients’ flow between them overlaid on the final approach which, for clarity, abandoned attempts to show patient flow and was integrated into a double page spread detailing the roles of different support teams.

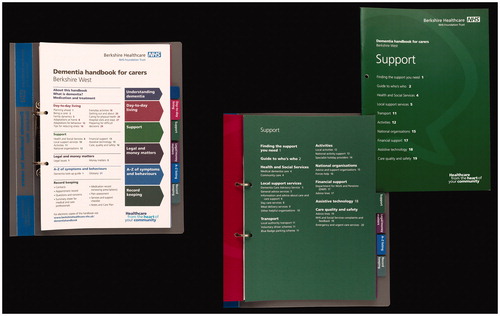

Document navigation

Overall structure was signalled by a colour-coded contents listing (, left), linked to tabbed, card separators for each booklet, included to help older users who might have reduced dexterity. The contents of each booklet were listed on the booklet covers and also card separators (, right). A translucent binder was used to reveal the contents and avoid confusion with other, colour-coded binders often used in care settings. As with the title for the handbook, the conflicting demands of accessibility and discretion were considered in binder selection, with the balance in favour of accessibility.

Pictures

Choosing pictures that were relevant, inclusive and realistic, proved challenging. Without a budget to commission photography or illustration, we used some photographic images from the NHS image database or, in some cases, created our own.

Branding

Both the NHS and the regional Healthcare Trust have brand guidelines. Our scoping consultation suggested that a clear NHS identity was important for carers but the local Trust identity had not been mentioned. The Trust brand guidelines included a decorative page footer, which we felt would become obtrusive in extensive documents. The Trust, sympathetic to our proposals for an uncluttered page, agreed to its removal. The Trust’s guidelines included an accessibility component based on widely used accessibility guidelines (UKAAF Citation2012), resulting in our one point of difference: our use of italics to highlight cross-references from the A–Z to component booklets. Although UKAAF guidelines allow the use of italic for small text elements such as these, we were asked to use quotation marks with roman text instead.

Print buying

Our initial funding proposal included a production budget for 4,000 copies but had not anticipated the modular, ring bound format we delivered. A lengthy print buying process ensued, in order to stay within budget, necessitating some trade-offs; for example, the binder quality was reduced, in order to retain features such as tabbed section dividers. Production costs are rarely covered in the discussion of healthcare design, often because reported research does not extend beyond prototyping and proof of concept. We mention costs because they can influence intervention effectiveness on implementation, or indeed, whether interventions are implemented at all.

Final feedback, editing and proofing

In a further stage of feedback, prototypes of the handbook with near-final content were reviewed over an extended time period by four carers and a professional who had not previously given feedback. Their feedback was incorporated before the handbook was submitted to the Trust communications team for approval for publication.

Evaluation

Following distribution of the handbook, we carried out a small-scale evaluation to establish whether, and how, it improved on the existing information that had triggered carer representatives’ complaints (see Introduction).

Part 1: baseline and post-implementation comparison of existing information and the handbook

Method

Before distribution of the published handbook, we administered a baseline questionnaire to carers attending Trust carer education courses. Following distribution we asked a second set of carers to take part in a two-week trial, using the handbook and, at the end of this period, administered a questionnaire to them. As noted earlier, carers attending education courses are a select group, already intent on improving their caring skills, and with the confidence to attend group courses, so may not be representative of all carers. The group will also have been primed to consider information provision in a way that participants in the baseline group had not. We, therefore, asked participants in the post-distribution group to indicate how much time they had spent looking at the handbook, the results suggesting that more than half had looked in some detail.

Participants were asked to rate on a scale of 1–4 (1 Not at all and 4 A lot) how their understanding of dementia and their feelings about their ability to cope with caring changed following:

receipt of post-diagnosis information (baseline group)

the handbook (post-distribution group)

information given during the carers’ course they had attended (baseline group).

Respondents and the method of analysis

There were 52 respondents in the baseline group of whom 32 had received post diagnosis information and attended the carer education course, the remaining 20 attending the carer course only. There were 29 in the post-distribution group. The data for each rating question were analyzed using Mann–Whitney U comparisons and significance evaluated with two-tailed tests.

Results

Of the post-distribution carer group, 6 had browsed the handbook quickly, 14 had looked in some detail, and 9 had read a large part; 8 had also looked up specific details.

shows the mean and mode for the baseline group’s ratings of existing, post-diagnosis information and the post-distribution group’s ratings of the handbook. The handbook was rated significantly higher than existing information for its influence on understanding of dementia (p < .05) but there was no significant difference in ratings of the two for influence on feelings of ability to cope.

Table 1. Mean and mode for baseline group ratings of existing, post-diagnosis information and post-distribution group ratings of the handbook.

shows the mean and mode for the baseline group’s rating of existing post-diagnosis information compared to their ratings of information received through the carer education course. The course had a highly significant impact on carers’ understanding of dementia compared to existing post-diagnosis information (p < .001) and a significant impact on their feelings of ability to cope (p < .05). In the ratings for the influence of the handbook on the post-distribution group are compared with the baseline group’s ratings of the carer course. Here, the handbook was still rated lower than the carer course, but the difference was only significant (p < .05) for the course impact on feelings of ability to cope with caring.

Table 2. Mean and mode for baseline group’s rating of post-diagnosis information compared to ratings of information received through carer education course.

Table 3. Post-distribution group ratings of the influence of the handbook compared with the baseline group’s ratings of the carer course.

Part 2: subsidiary questionnaire for people receiving the handbook

The post-distribution group was asked further questions, the responses to which are summarized below.

Participants rated the usefulness of the main sections of the handbook, on a scale of 1–4 (1 Not at all useful and 4 Very useful). As can be seen in , the mode for most sections was 3 (Useful).

Table 4. Post-distribution group’s ratings of the usefulness of the main sections of the handbook.

As we felt the record-keeping section would be the least likely to be appreciated (also confirmed by the ratings mean, see ), we asked whether participants had used this section. Ten responded that they had, with uses ranging from adding contact details, keeping appointment records and adding hospital discharge letters, doctor referrals and medication lists.

When asked whether they had gone back to the handbook after first looking at it, 14 responded positively, some reporting returning to it to look up specific information (e.g. the difference between Enduring and Lasting Power of Attorney), whereas others, still in evaluation mode, had returned to look at sections they had not covered previously. Fifteen participants said they had shown the handbook to someone else: 11 to family members, 4 to friends or other contacts; 3 also to the person they were caring for.

Respondents made some proposals for information that could be added in the future; for example, more detail on the options for supported living, such as flats with wardens and types of a care home; more on personal budgets (provided by Social Services to fund care).

In response to a final question on what was the most appropriate medium to deliver this sort of information, 11 responded paper, 13 paper or internet, and 3 internet only (2 did not respond).

Discussion

The rating comparisons in Part 1 of the evaluation suggest the potential benefits of purpose-designed information for dementia carers. We acknowledge the limitations of a two-week evaluation exercise, the select participant group, the different motivations behind the baseline and post-distribution groups' comments, and the power of the statistical tests used. The handbook’s impact appeared to be greatest in informing carers rather than building confidence in their ability to cope, which is more likely to develop from the experience of carer education courses (Jensen et al. Citation2015; Thompson et al. Citation2007).

The post-distribution group’s positive ratings of the different handbook sections and their consultations to answer specific questions confirmed that it met an information need. While the first two sections of the handbook were the highest rated, these were more discursive than some other sections, so the ratings may have been due to the ease of reading them. The A–Z of symptoms and behaviours was also highly rated, suggesting its potential to make an impact on future users, as did some carers’ spontaneous use of the record keeping section. Note, however, that we interpret the use of the record-keeping section cautiously as this level of uptake may have been characteristic, particularly, of this engaged user group.

Participants’ showing the handbook to other people may have been prompted by the novelty of participating in research, but may also indicate perceptions that the handbook was valuable and approachable.

Our question on presentation medium provided reassurance that by selecting print, rather than digital, presentation, we had included the majority of the evaluation group but we are also aware that, with time, the balance in responses is likely to shift towards digital presentation.6

Conclusion

In this article we provide a new perspective on information provision for families caring for people with dementia, highlighting information design. The initiative for the project came from carers themselves, as well as through professionals’ identification of design as significant in ensuring information delivery. In response we were able to give form to the information product, developing its content and planning its production to support its anticipated users. We acknowledge, however, that this focus on design was exceptional; the outcome of the relationship that had been built between designers and clinicians, specific funding and the commitment of all parties, funded or not, to the handbook’s development. In our discussion of the context for the project, we noted the growth of research and practice in health communication and this case study will add to a literature that builds an understanding of the benefits of partnership working to meet communication needs.

The initial post-distribution feedback indicated the handbook’s potential to improve access to information.7 Within this overall improved access, however, there may have been differences in experience that we did not capture. These are indicated, to some extent, in the different reading and consultation patterns of the feedback group. Furthermore, the capacity of the handbook to support families who are less engaged with dementia care than our study respondents remains unknown. Longer term, the impact of the handbook and return on investment could only be evaluated by extrinsic measures (Black et al. Citation2013), such as whether it saved time for professionals by reducing carers’ requests for information, or even reduced costly hospital admissions. Teasing out such impacts in a system as complex as the NHS would be difficult. Speculatively, however, preventing a single hospital admission, due to carers identifying symptoms of infection early enough for home treatment, would more than pay for the investment in information design, setting aside reduced distress for both patient and carer.

From this study, we can anticipate circumstances where similar effort might be particularly fruitful: where long term conditions necessitate patient or carer engagement with supporting services, and where existing information comes from disparate sources. We draw attention to the need highlighted in our research for information relating to local services and also to the reassurance to carers of information received directly from a trusted agency delivering care: in the UK, the NHS.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the many people who contributed their valuable time and experience to this research and resulting development of the handbook; Carol Brindley, Marielle Kay and Sylvia Roberts from the West Berkshire Memory Clinics; the carers and staff of the West Berkshire Memory Clinics; the Older People’s Mental Health Liaison Team at Royal Berkshire Hospital; carer representatives, Rebecca Day and Carol Munt; Claire Garley from Alzheimer’s Society; the staff and volunteers of Age Concern Woodley, and Alzheimer’s Society Reading. We are grateful to the Editor and reviewers of this article for their helpful comments on our submission.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Alison Black

Alison Black is Research Professor of User-centred Design in the Department of Typography & Graphic Communication, University of Reading. She is the director of the Department’s Centre for Information Design Research, which conducts research into the communication of complex information. She is co-editor of Information design research and practice (Routledge 2017).

Clare Carey

Clare Carey is an information designer and partner in Studio Lift, Reading, UK. She was formerly a researcher in Centre for Information Design Research, Department of Typography & Graphic Communication, University of Reading, where she worked on the Handbook for dementia carers and other health care communication projects.

Vicki Matthews

Vicki Matthews is Older Peoples Mental Health Services manager for Berkshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust. She is an occupational therapist by profession and HCPC member with 30 years of clinical and managerial experience in older peoples’ mental health.

Luke Solomons

Luke Solomons is a consultant in psychological medicine at Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. He is part of Oxford Psychological Medicine Research group’s HOME Study – an RCT on identification and management of psychological problems in older people in acute general hospitals – and the Oxford Cancer Centre Improving Care Study.

Notes

1 ‘Dementia’ is an umbrella term for a range of defined, progressive, neurodegenerative conditions, such as Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia etc.

2 Berkshire Healthcare Foundation Trust

3 Department of Health funded collaboration between The Design Council and design consultancy, PearsonLloyd, 2012. http://pearsonlloyd.com/a-better-aande/

4 The project was registered with Berkshire Healthcare Foundation Trust’s clinical governance and audit structure; the research received approval from University of Reading Research Ethics Committee and the UK Health Research Authority Research Ethics Committee.

5 Guidelines for writing for people with dementia are published by the Dementia Engagement and Empowerment Project (DEEP; http://www.dementiavoices.org.uk/deep-guides). Most of our writing and design decisions were compatible with DEEP guidance, but our use of two columns deviates from their recommendation. Note that we were designing for carers of people with dementia, although it is likely that the information in the handbook is also used by people with dementia.

6 In order to give wider access to the handbook, the Trust also uploaded a pdf version to its website (https://www.berkshirehealthcare.nhs.uk/media/168716/dementia-handbook.pdf). Even though this lacks the interactivity of a purpose designed electronic document, it has been accessed by users both within and beyond the Trust’s catchment area.

7 Subsequent adaptation of the handbook by other services also testifies to its perceived value among service providers. We prepared an e-book and app version, Dementia Guide for Carers and Care Providers, for trainee professional carers for Health Education England; approval was also given to another Trust to use the handbook as the basis for their own dementia guide.

References

- Anderson, K. A., K. A. Nikzad-Terhune, and J. E. Gaugler. 2009. “A Systematic Evaluation of Online Resources for Dementia Caregivers.” Journal of Consumer Health on the Internet 13 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1080/15398280802674560.

- Black, A., A. Gibb, C. Carey, S. Barker, C. Leake, and L. Solomons. 2013. “Designing a Questionnaire to Gather Carer Input to Pain Assessment for Hospitalized People with Dementia.” Visible Language 47 (2): 37–60.

- Black, A., and K. Stanbridge. 2012. “Documents as ‘Critical Incidents’ in Organisation to Consumer Communication.” Visible Language 46 (3): 246–281.

- Bouchier, H., and P. A. Bath. 2003. “Evaluation of Websites that Provide Information on Alzheimer’s Disease.” Health Informatics Journal 9 (1): 17–31. doi:10.1177/1460458203009001002.

- Bridges, J., S. Loukanova, and P. Carrera. 2008. “Patient Empowerment in Health Care.” In International Encyclopedia of Public Health, edited by K. Heggenhougen and S. Quah, 17–28. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

- Chang, E., S. Easterbrook, K. Hancock, A. Johnson, and P. Davidson. 2010. “Evaluation of an Information Booklet for Caregivers of People with Dementia: An Australian Perspective.” Nursing and Health Sciences 12 (1): 45–51. doi:10.1111/j.1442-2018.2009.00486.x.

- Corbett, A., J. Stevens, D. Aarsland, S. Day, E. Moniz-Cook, R. Woods, D. Brooker, and C. Ballard. 2012. “Systematic Review of Services Providing Information and/or Advice to People with Dementia and/or Their Caregivers.” International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 27 (6): 628–636. doi:10.1002/gps.2762.

- Coulter, A., and J. Ellins. 2007. “Effectiveness of Strategies for Informing, Educating, and Involving Patients.” British Medical Journal 335 (7609): 24–27. doi:10.1136/bmj.39246.581169.80.

- Ducharme, F., L. Levesque, L. Lachance, M. J. Kergoat, and R. Coulombe. 2011. “Challenges Associated with Transition to Caregiver Role Following Diagnostic Disclosure of Alzheimer Disease: A Descriptive Study.” International Journal of Nursing Studies 48 (9): 1109–1119. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.02.011.

- Forbes, S., M. Bern-Klug, and C. Gessert. 2000. “End-of-Life Decision Making for Nursing Home Residents with Dementia.” Journal of Nursing Scholarship 32 (3): 251–258. doi:10.1093/hsw/31.3.189.

- Fried, T. R., C. A. Redding, M. L. Robbins, J. R. O’Leary, and I. Iannone. 2011. “Agreement between Older Persons and Their Surrogate Decision-Makers regarding Participation in Advance Care Planning.” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 59 (6): 1105–1109. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03412.x.

- Hartley, J. 2012. “Designing Easy-to-Read Text.” In Writing Health Communication: An Evidence-Based Guide, edited by C. Abraham and M. Kools, 7–22. London, UK: Sage.

- Jackson, J., D. Bliss, K. Hepburn, C. Arntson, J. Mullins, and S. Rolnick. 2011. “The Development of Educational Materials to Assist Family and Friend Caregivers and Healthcare Providers in Caring for Persons with Incontinence and Dementia.” Clinical Medicine and Research 9 (3–4): 158. doi:10.3121/cmr.2011.1020.ps2-20.

- Jensen, M., I. N. Agbata, M. Canavan, and G. E. McCarthy. 2015. “Effectiveness of Educational Interventions for Informal Caregivers of Individuals with Dementia Residing in the Community: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials.” International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 30 (2): 130–143. doi:10.1002/gps.4208.

- Keller, H. H., D. Smith, C. Kasdorf, S. Dupuis, L. S. Martin, G. Edward, C. Cook, and R. Genoe. 2008. “Nutrition Education Needs and Resources for Dementia Care in the Community.” American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementiasr 23 (1): 13–22. doi:10.1177/1533317507312805.

- Kostelnick, C. 2017. “Social and Cultural Aspects of Visual Conventions in Information Design.” In Information Design Research and Practice, edited by A. Black, P. Luna, O. Lund, and S. Walker, 257–273. London, UK: Taylor and Francis.

- Mastwyk, M., D. Ames, K. A. Ellis, E. Chiu, and B. Dow. 2014. “Disclosing a Dementia Diagnosis: What Do Patients and Family Consider Important?” International Psychogeriatrics 26 (8): 1263–1272. doi:10.1017/S1041610214000751.

- Moys, J. L. 2014. “Typographic Layout and First Impressions – Testing How Changes in Text Layout Influence Readers’ Judgments of Documents.” Visible Language 48 (1): 41.

- Nelson, B. C., and T. J. Smith. 1990. “User Interaction with Maintenance Information a Performance Analysis of Hypertext versus Hard Copy Formats.” In Proceedings of the Human Factors Society Annual Meeting 34 (3): 229–233. Los Angeles, CA: Sage. doi:10.1177/154193129003400311.

- Newbronner, L., R. Chamberlain, R. Borthwick, M. Baxter, and C. Glendinning. 2013. A Road Less Rocky – Supporting Carers of People with Dementia. London, UK: The Carers Trust. Accessed 5 May 2017. https://professionals.carers.org/sites/default/files/dementia_report_road_less_rocky_final_0.pdf.

- Ong, L. M. L., J. C. J. M. de Haes, A. M. Hoos, and F. B. Lammes. 1995. “Doctor-Patient Communication: A Review of the Literature.” Social Science and Medicine 40 (7): 903–918. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(94)00155-M.

- Sanders, E. B. N., and P. J. Stappers. 2008. “Co-Creation and the New Landscapes of Design.” CoDesign 4 (1): 5–18. doi:10.1080/15710880701875068.

- Stajduhar, K. I., L. Funk, F. Wolse, V. Crooks, D. Roberts, A. M. Williams, D. Cloutier-Fisher, and B. McLeod. 2011. “Core Aspects of ‘Empowering’ Caregivers as Articulated by Leaders in Home Health Care: Palliative and Chronic Illness Contexts.” The Canadian Journal of Nursing Research 43 (3): 78–94.

- Stokes, L., H. Combes, and G. Stokes. 2015. “The Dementia Diagnosis: A Literature Review of Information, Understanding, and Attributions.” Psychogeriatrics 15 (3): 218–225. doi:10.1111/psyg.12095.

- Thompson, C. A., K. Spilsbury, J. Hall, Y. Birks, C. Barnes, and J. Adamson. 2007. “Systematic Review of Information and Support Interventions for Caregivers of People with Dementia.” BioMed Central Geriatrics 7: 18. doi:10.1186/1471-2318-7-18.

- Tsekleves, E., and R. Cooper. 2017. “Design for Health: Challenges, Opportunities, Emerging Trends, Research Methods and Recommendations.” In Design for Health, edited by E. Tsekleves and R. Cooper, 388–408. London, UK: Routledge.

- Van Der Waarde, K. 2010. “Visual Communication for Medicines: Malignant Assumptions and Benign Design?” Visible Language 44 (1): 39.

- UKAAF (UK Association for Accessible Formats). 2012. UKAAF minimum standards: Clear and large print. Document MS03. https://www.ukaaf.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/MS03-UKAAF-Minimum-standards-Clear-and-large-print.pdf Accessed 17 June 2019.

- Wackerbarth, S., and M. Johnson. 2002. “Essential Information and Support Needs of Family Caregivers.” Patient Education and Counseling 47 (2): 95–100. doi:10.1016/S0738-3991(01)00194-X.

- Wald, C., M. Fahy, Z. Walker, and G. Livingston. 2003. “What to Tell Dementia Caregivers: The Rule of Threes.” International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 18 (4): 313–317. doi:10.1002/gps.828.

- Walker, S. 2017. “Research in Graphic Design.” The Design Journal 20 (5): 549–559. doi:10.1080/14606925.2017.1347416.

- Walker, S., S. Hignett, R. Lim, C. Parkhurst, F. Samuel, and M. C. Mole. 2018. “Design, Architecture, Pharmacy: Making a Difference to Understanding Anti-Microbial Resistance (AMR)”. Paper presented at the Design4Health, Sheffield, September 4–6.

- Weih, M., A. Reinhold, T. Richter-Schmidinger, A. K. Sulimma, H. Klein, and J. Kornhuber. 2008. “Unsuitable Readability Levels of Patient Information Pertaining to Dementia and Related Diseases: A Comparative Analysis.” International Psychogeriatrics 20 (6): 1116–1123. doi:10.1017/S1041610208007576.

- Zender, P. M., W. B. Brinkman, and L. Widdice. 2017. “Design + Medical Collaboration: Three Cases Designing Decision-Support Aids.” In Information Design Research and Practice, edited by A. Black, P. Luna, O. Lund, and S. Walker, 655–668. London, UK: Routledge.