Abstract

This article discusses how research to understand the oral care needs and experiences of stroke survivors was translated into a prototypical intervention. It addresses the challenge of how to develop service improvements in healthcare settings that are both person-centred, through the use of co-design, and also based on theory and evidence. A sequence of co-design workshops with stroke survivors, family carers, and with health and social care professionals, ran in parallel with an analysis of behavioural factors. This determined key actions which could improve mouthcare for this community and identified opportunities to integrate recognized behaviour-change techniques into the intervention. In this way, behaviour change theory, evidence from qualitative research, and experience-based co-design were effectively combined. The intervention proposed is predominantly a patient-facing resource, intended to support stroke survivors and their carers with mouth care, as they transition from hospital care to living at home. This addresses a gap in existing provision, as other published oral-care protocols for stroke are clinician-facing and concerned primarily with acute care (in the first days after a stroke). Although it draws on the experiences of a single design project, this study articulates a ‘working relationship’ between design practice methods and the application of behaviour change theory.

Introduction

The behaviour of individuals can have important impacts on health outcomes for patient populations, so to optimize health outcomes, interventions to support or change specific behaviours may be needed. To be effective, behaviour change interventions need to be acceptable and feasible to implement for relevant populations, and should also draw on appropriate evidence and theory (Craig et al. Citation2008). This article describes the methods and outputs of a multidisciplinary research team, developing an oral-health intervention. The development work engaged stroke survivors, their carers, and their clinicians in aiming to improve oral-health behaviours. The development process was guided by the Experience-Based Co-Design (EBCD) process (Robert Citation2013; Point of Care Foundation Citation2020), and the Behaviour Change Wheel (Michie, Van Stralen, and West Citation2011; Michie, Atkins, and West Citation2014).

The research team combined clinical specialists in stroke and oral health with experts in design and in health psychology, and points of conjunction and mutual learning across approaches are discussed. As such, this article presents a worked example of how design and health specialisms can collaborate to define a complex intervention. In particular, it addresses the challenge of how to develop interventions that are co-designed, to ensure acceptability to patients and health care professionals, and also based on theory and evidence. Such considerations are of relevance to designers and design researchers working in health or care settings, where design methods would benefit from a more explicit evidence base (Niedderer, Clune, and Ludden Citation2017).

Case context

We aimed to develop an intervention to improve the oral health of stroke survivors living in the community by supporting self-care behaviours and enabling oral care support from carers. Each year, over 100,000 people in the UK have a stroke (Stroke Association Citation2018). Dental disease is highly prevalent in the stroke survivor population (Lyons et al. Citation2018, White et al. Citation2012). However, oral health is a relatively neglected part of stroke care (Horne et al. Citation2015; Talbot et al. Citation2005).

About a third of stroke survivors need help with activities of daily living after discharge from the hospital, and many experience disabilities that may impact their ability to manage their oral health (Stroke Association Citation2018), e.g. weakness in the hand/arm and swallowing problems. Research to date has largely focussed on oral care interventions for people hospitalized with a stroke (Lyons et al. Citation2018). How best to support stroke survivors with oral care after discharge into the community has received less attention, but it is important to ensure that appropriate support is in place for this population.

In Phase I of the research, we conducted interviews with 23 stroke survivors and focus groups with 19 health professionals to improve our understanding of the experience of stroke survivors and the context of the proposed intervention development (reported in O’Malley et al. Citation2020). Key issues identified included difficulties in carrying out oral hygiene self-care due to fatigue, forgetfulness and limb function, and dexterity problems. Routine seemed to be important for oral hygiene self-care but could be disrupted by hospitalization. For some, the aesthetic aspects of good oral care (e.g. a nice smile, fresh breath) were important. There appeared to be gaps in staff training and confidence in supporting patients with oral care, and problems with systems to ensure appropriate care was provided. Physical access to dental surgeries could be difficult.

Research approach

In Phase II, reported here, we drew on findings from Phase 1 and used a co-design approach: Experience-Based Co-Design (EBCD) (Robert Citation2013; Point of Care Foundation Citation2020), alongside the Behaviour Change Wheel (Michie, Van Stralen, and West Citation2011; Michie, Atkins, and West Citation2014) to theoretically inform intervention development. Co-design treats service users as ‘experts by experience’ (Visser et al. Citation2005). Benefits can include improved fit between the service offer and users’ needs, better service experience, and higher satisfaction (Steen, Manschot, and Koning Citation2011). A co-design approach seeks to maximize both intervention acceptability to stakeholders and the feasibility of implementing an intervention. It can also benefit service providers by promoting collaboration between disciplines and growing organizational capacity for innovation (Steen, Manschot, and Koning Citation2011). EBCD was chosen as it enables a full range of healthcare service stakeholders to participate in patient-centred service improvement, is time-managed, and is a recognized model within the UK NHS, where it originated as ‘Experience-Based Design’ (Bate and Robert Citation2006; NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement Citation2009; Robert Citation2013).

Whilst EBCD can be facilitated as a design process without expert designers, prominent early theories of co-design (Sanders and Stappers Citation2008) and recent empirical studies, suggest that using designer-facilitators has advantages in improving participants’ design capabilities and generating more innovative intervention outcomes (Dimopoulos-Bick et al. Citation2019; Ramos et al. Citation2020). In the current study, EBCD workshops were facilitated by experienced designer-researchers, drawing on a range of creative design tools to facilitate the co-design workshops, in line with the ‘designerly’ approach to co-design described by Robert and Macdonald (Citation2017).

To make sense of the data emerging from the EBCD workshops, Service Design methods were chosen. Service Design methods involve the visualization of patient experiences on a timeline and are increasingly used to develop person-centred pathways in healthcare (Malmberg et al. Citation2019). We envisaged that articulating service-user-journeys for stroke survivors and their family carers, and integrating these into a Service Blueprint (Bitner et al. Citation2008) would provide a flexible way to visualize a joined-up provision despite the involvement of multiple provider organizations (Neilsen Norman Group Citation2020; Lievesley and Wassall Citation2015) and would guide the subsequent development of the intervention.

Although professional design agencies increasingly engage behavioural specialists (Lockton, Harrison, and Stanton Citation2010), most published case material on designing for behaviour change focuses on market impact without explanation of what principles, theories, or tools are used in development (Niedderer, Clune, and Ludden Citation2017). Behaviour change theories provide useful guidance when developing interventions by identifying the factors likely to be relevant to understanding, predicting, and changing behaviour. The Medical Research Council (MRC) guidance for developing and evaluating complex interventions highlights the importance of drawing on existing evidence, and of either identifying or developing a theory on which to base an intervention (Craig et al. Citation2008).

There are many decisions to be made when designing an intervention, for example: which theoretical factors are most relevant and most feasible to target in a specific context? The Behaviour Change Wheel is a framework designed to guide the researcher in negotiating such issues (Michie, Atkins, and West Citation2014: Michie, Van Stralen, and West Citation2011). At the centre of the ‘Wheel’ is the COM-B model, which proposes that ‘Capability’, ‘Opportunity’, and ‘Motivation’ interact in producing ‘Behaviour’. Capability is ‘the individual’s psychological and physical capacity to engage in the activity concerned’ (includes knowledge and skills); opportunity is ‘the factors that lie outside the individual that make the behaviour possible or prompt it’; motivation is ‘all those brain processes that energize and direct behaviour’ (includes conscious processes as well as habitual and emotional processes) (Michie, Van Stralen, and West Citation2011, 6). The next layer of the Wheel is ‘intervention functions’ (ways in which an intervention can change behaviour): education, persuasion, incentivization, coercion, training, enablement, environmental restructuring, and restrictions. In the outer ring are policy categories that would support intervention delivery, e.g. guidelines, legislation, service provision, and fiscal measures.

A related approach is the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF), which synthesized theoretical factors from a range of theories, using a consensus approach, yielding 14 theoretical domains (Cane, O’Connor, and Michie Citation2012). The TDF domains relate to the broader COM-B categories and can be used in conjunction with the Behaviour Change Wheel, supporting a more detailed behavioural analysis (Michie, Atkins, and West Citation2014).

In summary, this study aimed to produce an intervention with maximal acceptability and fit with existing patterns of care, and optimal potential for enhancing behaviours relevant to stroke survivor oral health by combining a co-designing approach (EBCD), with behaviour change theory (Behaviour Change Wheel and TDF).

Methods

Overview

The research was conducted in the North West of England and explored the experiences of stroke survivors treated in UK National Health Service (NHS) hospitals. Health and social care professionals (HSCPs) were also based within publicly funded services or relevant regional, voluntary sector organizations. The study was reviewed and granted favourable ethical opinion by the NRES Committee Northwest Haydock Research Ethics committee (REC Ref No: 17/NW/0335). The study was conducted according to the standards of the European Medicines Agency Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice (Kingham, Bogaert, and Eddy Citation1994).

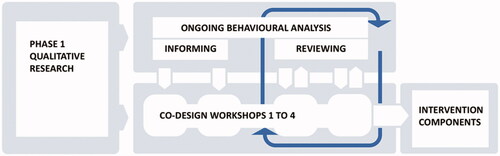

A behavioural analysis, informed by the Behaviour Change Wheel staged approach, was combined with four co-design workshops across 9-weeks, involving either stroke survivors (with family carers), HSCPs, or both. We describe the use of the Behaviour Change Wheel first, and then the experience-based co-design workshops. In reality, the two processes were iterative rather than chronologically separate (see ).

Use of the behaviour change wheel to inform intervention development

Stages outlined in Michie, Atkins, and West (Citation2014) guide to using the Behaviour Change Wheel were followed.

Understanding the behaviour

This stage aimed to: specify what the behavioural problem is; specify the behaviours that need to change and who needs to carry out the behaviours; and understand what the behavioural determinants are (the factors are that need to change to change the specified behaviour). This stage was led by a Health Psychologist with expertise in behaviour change (author Powell), in parallel with the Phase 1 thematic analysis of qualitative data (by author O'Malley), such that the understanding of the behaviour was grounded in the Phase 1 data.

The target oral hygiene behaviour was selected as cleaning the teeth/mouth twice a day, a behaviour that would be performed by the stroke survivor, an informal caregiver, or professional caregiver. The target dental care behaviour was: accessing dental care (e.g. visiting dentist), a behaviour performed by the stroke survivor. Detailed initial specifications of these two behaviours are provided in and .

Table 1a. Initial specification for target behaviour ‘cleaning teeth/mouth’.

Table 1b. Initial specification for target behaviour ‘accessing dental care’.

We used the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) to guide our identification of behavioural determinants. For example, one domain within this framework is ‘physical skills’. The TDF, therefore, guides us to consider whether ‘physical skills’ is a factor affecting whether or not someone carries out oral care behaviours, and Phase 1 data would enable an understanding of how physical skills might be important in the present context (e.g. impaired hand functioning affecting the ability to clean teeth).

The identification of behavioural determinants was initially conducted based on the analysis of Phase 1 data. This behavioural analysis was further informed by discussions from the first two EBCD workshops. Supplementary Appendix 1 contains details of this process for the behaviour of cleaning teeth/mouth by stroke survivors as an example. Important factors influencing this specific behaviour appeared to be: physical skills (e.g. strategies to clean teeth despite physical limitations); knowledge; cognitive skills; memory (forgetting was common, especially when tired); behavioural regulation (importance of habit/routine); environmental context (e.g. tools; access to bathrooms); social influence (e.g. practical help and reminders from caregivers); beliefs about consequences; goals; emotion.

For the behaviour of cleaning teeth/mouth by caregivers, important factors seemed to be: physical skills; knowledge; cognitive and interpersonal skills; environmental context and resources (e.g. time; the need for oral care to be specified in care plans); social influences; professional/social role and identity; beliefs about capability (lack of confidence in cleaning another’s teeth seemed common); and beliefs about consequences and emotion.

Finally, important factors determining accessing dental care by stroke survivors appeared to be: knowledge (including knowing how to find a suitable dentist); cognitive and interpersonal skills; memory; environmental context, and resources (e.g. availability of NHS dentists willing to accept stroke survivors; accessibility of practices); and social influences.

This behavioural analysis informed the EBCD process, ensuring that issues identified as potentially important during Phase 1 and initial workshops were considered as intervention development progressed.

Identifying intervention options and potential content

Potential intervention functions and policy categories were identified following guidance by Michie, Atkins, and West (Citation2014). For example, ‘training’ was identified as an intervention function to support the need for physical skills, and potential policy categories for the intervention function ‘training’ included service provision and guidelines. Possible behaviour change techniques were then identified. A behaviour change technique is ‘an active component of an intervention designed to change behaviour’ (Michie, Atkins, and West Citation2014, 145). A taxonomy of behaviour change techniques has been developed to optimize accurate reporting and understanding of intervention components (Michie et al. Citation2013). For example, one behaviour change technique is prompts/cues (‘Introduce or define environmental or social stimulus with the purpose of prompting or cueing the behaviour’, Michie, Atkins, and West Citation2014, 268). Author Powell mapped potential intervention functions to possible behaviour change techniques (see Supplementary Appendix 2 for an example of this process for the behaviour of cleaning teeth/mouth by stroke survivors).

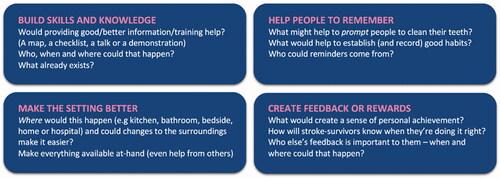

This theoretical-based approach does not dictate the exact content of an intervention but instead provides a range of options for consideration. In the present study, this staged analysis informed discussions in the early EBCD workshops. For example, it was used as the basis for four plain-language, flash-card-style prompts to stimulate ideas from Workshop participants (see ). The prompts indicated broad approaches within which specific ideas could be defined. In this way, evidence and theory were used to inform and scaffold the co-design process, but did not dictate intervention design. For the intervention to be truly responsive to the needs and desires of stroke survivors and professionals, it was important to prioritize their views as to how the challenges of the target behaviours could be addressed—we did not wish to restrict discussions or the creativity of the EBCD process.

During EBCD workshops and through interactions with the research team led by the first author, speculative intervention components were suggested, which addressed the behavioural analysis outlined in Stage 1 above. Author Powell analysed these, identifying which behaviour change techniques were being used in each case. They also worked with the design authors to advise on issues, such as wording, where the designer’s intent was in line with a specific behaviour change technique, but minor changes were needed to maximize the chances of effectively promoting behaviour change. This approach would ensure that components would contain identifiable ingredients that would be theoretically expected to be effective. This mapping was regularly updated and developed as the intervention became more clearly defined through the design process. The final version is shown in .

Use of experience-based co-design to develop the intervention

Four EBCD workshops enabled service users and staff to explore key issues and to define the key elements and format of the proposed intervention, with the aim of understanding and increasing the acceptability of the end result (Diepeveen et al. Citation2013).

Co-design participants

Seven stroke survivors, two family carers, and 16 HSCPs took part in at least one of four co-design workshops between March and May 2019. Stroke survivors’ ages ranged from 41 to 70, four were male, and three were female. Five had experienced a single stroke; two had experienced two strokes. The time since the most recent stroke ranged from one to eight years. Both carers were female and aged in their sixties. The HSCP participants included individuals with roles in hospitals, community healthcare, social care, and voluntary sector services, representing all stages in the sequence of stroke care. They were dental/oral health practitioners (including dental nurses) (6), occupational therapists (2), stroke nurses (2), speech and language therapists (2), stroke support officer (1), social worker (1), dietician (1), health care assistant (1). Years since qualification ranged from 4 to 38, and the number of years’ experience working with stroke survivors ranged from 3 to 34.

Procedure

The aims of the EBCD process were to consider the target behaviours, behaviour change techniques, and the content and mode of delivery of the proposed intervention. Workshop activities also explored barriers to implementation and optimal timing for the provision of the intervention. All workshops included a briefing, making the EBCD process transparent to all participants (following Reay et al. Citation2017), and up to 90 min of activities. They were conducted within a hospital or community-centre settings. Data were collected as audio recordings, facilitators’ notes, paper mock-ups of possible intervention components (prototypes), and sticky notes written by participants, assembled into visual documents. These documents and co-created prototypes were the primary data outputs from the workshops, with audio recordings used to support the recall.

Trigger-films (Point of Care Foundation Citation2020) were used to punctuate each of the co-design workshops, setting the agenda, along with a series of paper-based activities, prompts, and workbooks. Constructed using video clips from Phase I interviews, the films reinforced the patient voice within the design process (Point of Care Foundation Citation2020; Ramos et al. Citation2020) and brought focus to key topics identified in the behavioural analysis, creating a candid portrait of current service provision.

Workshop 1: Stroke survivors and carers explored whose advice they had found important during their recovery and how they would advise others entering the care of a stroke service. Different stroke-survivor Personas (Jones Citation2013) were developed for this purpose. The participants were encouraged to share observations about their lived experiences of care at all stages of the stroke service journey.

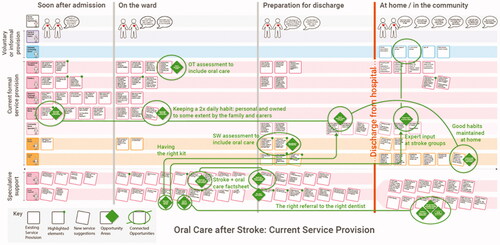

Workshop 2: The HSCPs constructed a step-by-step map of current service provision, covering pre- and post-discharge (). Each participant’s activities and contributions to care were noted and organized into individual sequences, before being aggregated into the mapping document, which stimulated a rich discussion. Seven disciplinary specialisms were represented, highlighting key steps, and the temporal relationships between them, which comprised the current provision.

Participants were asked to respond to a range of written challenges e.g. ‘some stroke survivors lose their brushing/care habits during their hospital stay’. The HSCPs identified changes that might be made to address these challenges. To support the discussion, four prompts were used (). The four areas were consistent with intervention functions identified as being potentially relevant in the earlier behavioural analysis: education, persuasion, training, environmental restructuring, modelling, enablement, and incentivization.

Figure 2. A prompt document with four sections, drawing on approaches from the behavioural analysis, was used to encourage discussion and generate improvement ideas.

Design Synthesis 1: Design Synthesis 1 involved reflecting on data generated in workshops 1 and 2, and the Phase 1 qualitative findings, in relation to the target behaviours. The synthesis involved the physical organization and reorganization of the data in search of relationships or patterns that could be translated into actionable insights (English Citation2006; Kolko Citation2010). In this study, the stroke-survivor and HSCP workshop data were reorganized along a common timeline, highlighting potential opportunity areas identified by both sets of stakeholders. These were phrased as successful outcomes, for example: ‘good habits maintained at home’ or ‘having the right kit’, and were then overlaid onto the map of existing service provision built during Workshop 2. The digitized version of the map created in Workshop 2 is shown here, complete with all opportunity areas identified overlaid as green diamonds. Green lines connect recurring themes.

The opportunity areas were sequenced into an improved User Journey. Following the Service Blueprinting method (Bitner et al. Citation2008), the details of this User Journey were explored, in terms of the people, places, artefacts, and responsibilities needed to realize improvements (Neilsen Norman Group Citation2020). The improvement ideas were developed into a set of prototypical intervention components to develop in Workshops 3 and 4. They were mainly in the form of printed paper mock-ups, unfinished, but coherent enough to provoke discussion, critique, acceptance, or rejection (Wensveen and Matthews Citation2015).

Figure 3. Map of existing service-provision at the research site, discipline by discipline, across 4 time phases: Soon after admission (hospital) | on the ward | preparing for discharge | at home/in the community.

Workshop 3: Stroke survivors and carers reviewed, critiqued, and improved the prototypes, in terms of information content, legibility of text and images, and timing/modes of use. Feedback was recorded by the facilitators, and recommended adaptations were made to the mock-ups. These refined prototype proposals were also checked against the behavioural analysis. This step was important to ensure that key behavioural determinants of the target behaviours were being addressed and to identify where behaviour change techniques might be clearly relevant but absent.

Workshop 4: Stroke survivors, carers, and HSCPs together, examined each prototypical intervention component through two activities: First, each participant reviewed 2 or 3 components, selected according to their own expertise. In personalized workbooks, they answered questions, such as: How would this best fit into existing patterns of workflow? (who? where? when?); and: What would you add to this idea? Next, the cohort split into three themed groups to discuss the means and viability of implementing the proposed components. Together, these activities provided a structured critique of the components.

Design Synthesis 2: Data collected in all workbooks, and all adaptations or suggestions made directly to the mock-ups, were transcribed to a spreadsheet for cross-referencing and used to inform the final round of prototype development. Where specific additional expertise was needed, e.g. to agree on terminology, or to understand commissioning processes, the research team sought that advice after the workshops.

Based on this final input from all stakeholders, the intervention components were rationalized in number and final design refinements were made. They were organized into three subsets based on the timing of their provision and the draft Service Blueprint was updated. Together, this set of mock-ups and the corresponding Blueprint define the proposed intervention.

Results

In this section, we describe the Improved User Journey, the Service Blueprint, and a short summary of the 13 potential intervention components.

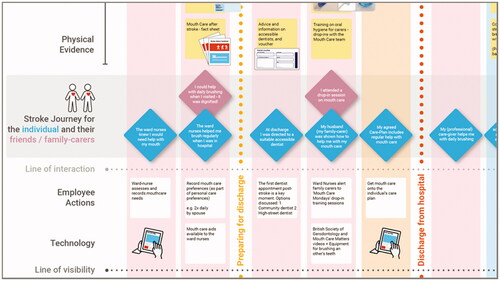

Improved user journey

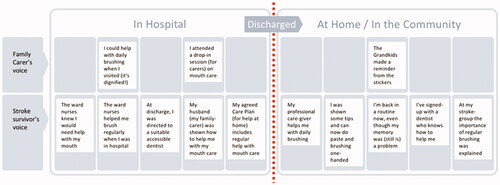

The Improved User Journey is composed of the series of encounters that a stroke survivor and their informal carer might experience in a revised and improved service (see ). The following examples illustrate how the data from the workshops were cross-matched to identify where suggestions from the different participant groups related closely to each other, and how this synthesis process informed the improved user journey.

Example 1: engaging family carers: In Workshop 2, a dental professional talked about having an ‘oral health kit with appropriate resources – not the usual kit’ for in-hospital mouthcare – and a Stroke nurse suggested ‘encourage the family to assist with mouth care—Do they need training?’. Thinking about people returning home, a community-based nurse asked ‘do family carers need training in mouthcare?’ and the Social Worker identified an opportunity to provide ‘training on oral hygiene and denture care – for carers and family members’. This resonated with Workshop 1 data from stroke survivors ‘being given the wrong things at the wrong time’ and also with a finding from the Phase I interview data – that the stroke and consequent hospital stay can interrupt a person’s pre-existing good-habits – leading to a loss of daily brushing (O’Malley et al. Citation2020).

Example 2: mouthcare in the care plan: An Occupational Therapist (OT) had highlighted that not all OTs checked whether stroke survivors due to be discharged could brush their own teeth – because it is not currently on the EPR (the Electronic Patient Record), which serves as a discharge checklist. Similar EPR limitations were raised by a Social Worker regarding their Care Needs Assessment tool, which determines the support a person leaving hospital will receive from professional caregivers, once they return home. If mouthcare is not included as an EPR check-box at discharge, it could be overlooked, resulting in professional caregivers not being instructed to provide it post-discharge.

The series of opportunity areas synthesized from the Workshop data in this way were first mapped to current service provision () and then refined and organized into a notional, improved user journey (). This was formulated in the voices of a stroke survivor and carer to explain an improved experience of care in a person-centred way. For example, Family Carer’s voice: ‘I attended a drop-in session on mouth care’; Stroke survivor’s voice: ‘My husband (family-carer) was shown how to help me with my mouth care’.

Service blueprint

The Improved User Journey was then used as the core of a Service Blueprint, based on Neilsen Norman’s format (2020), an excerpt of which is shown in .

Figure 5. Excerpt from the Service Blueprint drafted to synthesize the findings from Workshops 1 and 2 and to define a range of prototypical elements of the intervention. The full document can be viewed in Supplementary Appendix 3.

A range of potential intervention components was identified in relation to the user journey. When these were cross-checked to the behavioural analysis, areas which could be enhanced, such that intervention components aligned with recognized behaviour change techniques, were identified.

Example 3: learning new techniques: It was identified that when helping individuals to learn how to carry out behaviours, the behaviour change technique ‘Demonstration of the behaviour’ was relevant (i.e. ‘showing’ could be beneficial in addition to ‘telling’). This tied into an insight from Workshop 3, that smartphones were regularly used on the ward by family visitors, usually for looking-up medical or pharmaceutical information. With these insights, a proposed factsheet (C2 below) was amended to incorporate links to web-based video demonstrations (such as how to safely brush another person’s teeth).

Other rows in the Blueprint enabled the research team to consider supporting actions and resources needed to make each step possible. It also enabled the likely ownership of each element to be considered across the range of health, social care, and voluntary sector organizations that may be involved in the delivery of the intervention. In all, the Blueprinting process identified thirteen potential intervention components, which could support the improved user journey.

Potential intervention components

The potential intervention components developed are summarized in . Alongside, are the Behaviour Change Techniques included in the final versions of each. An expanded table including Intervention Functions and Policy Categories is available in Supplementary Appendix 4.

Table 2. The set of prototypical intervention components is identified through the synthesis process.

Prioritized intervention components

The feedback from Workshop 4 participants, on how the proposals might best fit into existing patterns of care, helped to prioritize (see Supplementary Appendix 4) and cluster nine of the original thirteen intervention components around three milestones in care, i.e. key opportunities for intervention within the stroke-journey (see examples in ).

Table 3. Proposed timing of delivery of the prioritized intervention components.

Discussion

In this study, behaviour change theory, evidence from qualitative research, and experience-based co-design were effectively combined to develop the structure, format, and content of an intervention promoting good mouth care for stroke survivors. The proposed intervention aims to enhance the oral-care support needed by stroke survivors following hospital discharge, where appropriate provision has previously been poorly defined (Lyons et al. Citation2018). It includes guidance on self-care, accessing a suitable dentist; getting help from professional care-givers; managing memory problems; and support provided via community-based groups.

The intervention as a whole is in prototypical form, with components that are developed to different levels of readiness for implementation. For example, the Factsheet (C2), Mouth Care Mondays agenda and poster (C5 + C6), and Expert Input at Stroke Groups (C13) are complete and fully defined. Other elements, such as the Toothbrushing Charts (C3 + C4), are well-defined in terms of what they are and why they are needed, but the complex set of interactions they invoke, between families and staff and the ward environment, needs further testing and iteration. This will be the subject of follow-on work.

Design methods, particularly in co-design and particularly in complex settings, such as healthcare, put emphasis on making progress and improvement rather than pursuing perfect, complete solutions (Norman and Stappers Citation2015). The lead workshop facilitator’s previous healthcare design experience was an important enabler (following Ramos et al. Citation2020) in encouraging and exploring ways to overcome blockers. In our study, for example, two desirable changes to the Electronic Patient Records (EPR) system, identified in Workshop 2 (C7 + C9), would have been optimal ‘solutions’ by mandating certain actions but were confounded by a long (2-year) delay between software-change-cycles. These two technology-driven checks were successfully ‘reframed’ (Dorst Citation2011) as conversations we want to happen, and the following person-centred alternatives developed instead. First, the Poster Prompt for the Ward Bathroom (C1) promotes the idea of independent brushing to all and explicitly grants permission to patients to ask about it. Second, the Voucher (C8) prompts a specific conversation with the Social Worker at the point of discharge, drawing attention to a mouth care needs-assessment—substituting for an EPR-mandated check (C9). So, whilst the EPR changes remain a longer-term goal, in the interim, these two alternatives still prompt relevant and timely actions in the care pathway. The alternatives described demonstrate the capacity of design to promote flexible and pragmatic approaches, to confront institutional barriers, and still make progress (Cross Citation2011).

A theory-informed and evidence-based development process was followed and the theoretical tools and frameworks used are made explicit, answering Niedderer’s call for better-documented processes from design teams (Niedderer, Clune, and Ludden Citation2017), and MRC recommendations for complex intervention design (Craig et al. Citation2008). The design practice community will recognize the importance of being able to demonstrate an explicit and consistent approach to defining behaviour as an integrated part of design methods.

At first glance, the two approaches combined in this study may appear to be very different. The lead author is a Designer-Researcher and led the EBCD approach, which centres on design group participants’ experiences and expressed needs, and creative development of an intervention. The second author is a Health Psychologist who led the use of the Behaviour Change Wheel approach, which proposes a pathway to intervention design in line with available evidence and theoretical frameworks. However, co-design workshops produce a type of evidence that can feed into the Behaviour Change Wheel approach. Further, the Behaviour Change Wheel approach proposes that interventions are assessed against APEASE criteria: affordability; practicability; effectiveness and cost-effectiveness; acceptability; side-effects/safety; and equity (Michie, Atkins, and West Citation2014), issues that are likely to be considered in an EBCD group.

Nevertheless, the differences in approach between these two researchers needed some consideration. Whilst both disciplines value the experiences, observations, and insights of the EBCD group members, the Health Psychologist’s approach also focussed on incorporating previous evidence (from the literature and from the Phase 1 related research) and behaviour change theory into intervention design. This study was the first time that these two researchers had worked together to integrate the two approaches, and there were, at times, differences in language and approach that neither had anticipated. Working through these matters led to beneficial learning for both parties, a research process, and the final result, that neither discipline could have achieved alone. We would recommend that researchers from two such different disciplines build in time to: articulate their expectations and assumptions early in the process; to jointly shape the EBCD workshop agendas and tools; and to reflect together on the data generated after each workshop.

Useful intersection points have been identified through this case, where behavioural theory can augment design methods without restricting the creative process. First, by using the Behaviour Change Wheel (BCW), target behaviours in both the stroke survivor and family/informal carer populations were made explicit (), strengthening and clarifying the design brief. Second, drawing on evidence gained in phase 1 interviews, the use of the BCW allowed the identification of potential intervention functions and behaviour change techniques. These findings were used as prompts () to scaffold (not prescribe) the co-designing workshop activity. Third, in the synthesis work between workshops, coding each intervention component using the Behaviour Change Technique taxonomy (Michie et al. Citation2013) helped to tailor the intervention content to maximize effectiveness (detailed in and ). This also means that each intervention component is clearly defined in terms of its behaviour change ingredients, which enables the accurate reporting of the intervention components and will facilitate replication and future evaluation.

Other health intervention development research has combined behaviour change theory with co-design interventions, but the process for combining approaches has varied. Some used behaviour change models, such as COM-B to construct prototypical intervention components, before co-design workshops (e.g. Aljaroodi et al. Citation2017; Bonner et al. Citation2019). At least one study has successfully engaged patients as co-designers during the later stages of a theory-informed intervention development process (e.g. Salmon et al. Citation2019). In our research, we drew on co-design input both to explore initial priorities and also to shape two cycles of prototype development and integrated behaviour change theory throughout, i.e. to inform each workshop agenda and to evaluate and optimize emerging intervention prototypes.

The intervention development described was based on a single locality, so it will be important to gain wider feedback on the intervention components, to ascertain their fit with practice across other regions. The next stage will involve evaluating the effectiveness of the intervention in improving oral health care in stroke survivors.

Conclusions

This project has addressed a highly complex health issue, combining methods from Design and Health Psychology to develop an intervention aiming to maximize acceptability, the feasibility of implementation, and effectiveness. The outcome is predominantly a patient-facing resource intended to provide continued support for stroke survivors post-hospital discharge, and as such will address a gap in current provision.

Design, with its user-centred philosophy, has great potential to help health and care service providers make progress towards genuinely person-centred care. However, the design’s socially constructed approach does not easily demonstrate the rigour valued by healthcare commissioners. Through this case, a theory-informed development process has been described where the rigour is made explicit as part of the project outputs. It articulates a ‘working relationship’ between design practice methods and the application of behaviour change theory.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (568.4 KB)Acknowledgements

We thank our research participants who made this work possible, particularly stroke survivors and carers who shared their stories and insights. Thanks to Salford Royal NHS Foundation Trust for sponsoring and hosting the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Matthew Lievesley

Matthew Lievesley is an Associate Professor in Design. His research explores how design methods, including co-design and service design, enable the development of person-centred health and care services.

Rachael Powell

Rachael Powell is Senior Lecturer in Health Psychology. Her research interests include how to support individuals during healthcare processes, and behaviour change in health contexts.

Daniel Carey

Daniel Carey is a service designer specializing in health and social care. He has a particular interest in co-design approaches to develop patient-led support services.

Sharon Hulme

Sharon Hulme, now retired, was formally Senior Research Manager for the Stroke Research Theme, Division of Cardiovascular Sciences, University of Manchester.

Lucy O’Malley

Lucy O’Malley, Senior Lecturer, University of Manchester. Lucy is a social scientist with expertise in medical sociology and health psychology and researches oral health behaviours.

Wendy Westoby

Wendy Westoby is a retired Dental Nurse who had a stroke in 2009 and now contributes to many research projects, sharing her experience and expertise in life after stroke.

Jess Zadik

Jess Zadik is an NHS Research Engagement Manager, with experience in stakeholder engagement and leads on improving equity of access and increasing participation in research.

Audrey Bowen

Audrey Bowen is a Professor of Neuropsychological Rehabilitation. Her research aims to develop the evidence base for neurorehabilitation, specializing in cognitive and communication difficulties and patient and carer involvement.

Paul Brocklehurst

Paul Brocklehurst is a Consultant in Dental Public Health and an Honorary Professor in Health Services Research at Bangor University with an interest in co-design.

Craig J. Smith

Craig J. Smith is a Professor of Stroke Medicine. His research addresses the role of infection and inflammation in cerebrovascular disease, with a focus on oral healthcare after stroke.

References

- Aljaroodi, Hussain M., Marc T. P. Adam, Raymond Chiong, David J. Cornforth, and Mario Minichiello. 2017. “Empathic Avatars in Stroke Rehabilitation: A co-Designed mHealth Artifact for Stroke Survivors.” In International Conference on Design Science Research in Information System and Technology, No. 10243, 73–89.

- Bate, Paul, and Glenn Robert. 2006. “Experience-Based Design: From Redesigning the System around the Patient to Co-designing Services with the Patient.” Quality & Safety in Health Care 15 (5): 307–310. doi:10.1136/qshc.2005.016527.

- Bitner, Mary Jo, Amy L. Ostrom, and Felicia N. Morgan. 2008. “Service Blueprinting: A Practical Technique for Service Innovation.” California Management Review 50 (3): 66–94. doi:10.2307/41166446.

- Bonner, Carissa, Michael Anthony Fajardo, Jenny Doust, Kirsten McCaffery, and Lyndal Trevena. 2019. “Implementing Cardiovascular Disease Prevention Guidelines to Translate Evidence-Based Medicine and Shared Decision Making into General Practice.” Implementation Science 14 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1186/s13012-019-0927-x.

- Cane, James, Denise O’Connor, and Susan Michie. 2012. “Validation of the Theoretical Domains Framework for Use in Behaviour Change and Implementation Research.” Implementation Science 7 (1): 37. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-7-37.

- Craig, Peter, Paul Dieppe, Sally Macintyre, Susan Michie, Irwin Nazareth, and Mark Petticrew. 2008. “Developing and Evaluating Complex Interventions: The New Medical Research Council Guidance.” BMJ 337: a1655. doi:10.1136/bmj.a1655.

- Cross, Nigel. 2011. Design Thinking: Understanding How Designers Think and Work. Berg.

- Diepeveen, Stephanie, Tom Ling, Marc Suhrcke, Martin Roland, and Theresa M. Marteau. 2013. “Public Acceptability of Government Intervention to Change Health-Related Behaviours: A Systematic Review and Narrative Synthesis.” BMC Public Health 13 (1): 756. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-756.

- Dimopoulos-Bick, Tara L., Claire O'Connor, Jane Montgomery, Tracey Szanto, Marion Fisher, Violeta Sutherland, Helen Baines, et al. 2019. “Anyone Can Co-design?”: A Case Study Synthesis of Six Experience-Based co-Design (EBCD) Projects for Healthcare Systems Improvement in New South Wales, Australia.” Patient Experience Journal 6 (2): 93–104. doi:10.35680/2372-0247.1365.

- Dorst, Kees. 2011. “The Core of ‘Design Thinking’ and Its Application.” Design Studies 32 (6): 521–532. doi:10.1016/j.destud.2011.07.006.

- English, Stuart. 2006. “Design thinking-Value Innovation-Deductive Reason and the Designers Choice.” In Proceedings of the Design Research Society Conference, Lisbon, 1–4.

- Horne, Maria, Giles McCracken, Angus Walls, Pippa J. Tyrrell, and Craig J. Smith. 2015. “Organisation, Practice and Experiences of Mouth Hygiene in Stroke Unit Care: A Mixed‐Methods Study.” Journal of Clinical Nursing 24 (5–6): 728–738. doi:10.1111/jocn.12665.

- Jones, Peter. 2013. Design for Care: Innovating Healthcare Experience. New York, NY: Rosenfeld Media, 77–78.

- Kingham, Richard F., Peter W. L. Bogaert, and Pamela S. Eddy. 1994. “The New European Medicines Agency.” Food & Drug LJ 49: 301.

- Kolko, Jon. 2010. “Abductive Thinking and Sensemaking: The Drivers of Design Synthesis.” Design Issues 26 (1): 15–28. doi:10.1162/desi.2010.26.1.15.

- Lievesley, Matthew, and Rebecca Wassall. 2015. “Designing across Organisational boundaries-Community Dentistry Services.” In Proceedings of the Third European Conference on Design4Health 2015. Newcastle University.

- Lockton, Dan, David Harrison, and Neville A. Stanton. 2010. “The Design with Intent Method: A Design Tool for Influencing User Behaviour.” Applied Ergonomics 41 (3): 382–392. doi:10.1016/j.apergo.2009.09.001.

- Lyons, Mary, Craig Smith, Elizabeth Boaden, Marian C. Brady, Paul Brocklehurst, Hazel Dickinson, Shaheen Hamdy, et al. 2018. “Oral Care after Stroke: Where Are We Now?” European Stroke Journal 3 (4): 347–354. doi:10.1177/2396987318775206.

- Malmberg, Lisa, Vanessa Rodrigues, Linda Lännerström, Katarina Wetter-Edman, Josina Vink, and Stefan Holmlid. 2019. “Service Design as a Transformational Driver toward Person-Centered Care in Healthcare.” In Service Design and Service Thinking in Healthcare and Hospital Management, 1–18. New York, NY: Springer Cham.

- Michie, Susan, Lou Atkins, and Robert West. 2014. “The Behaviour Change Wheel.” In A Guide to Designing Interventions. Sutton: Silverback Publishing.

- Michie, Susan, Michelle Richardson, Marie Johnston, Charles Abraham, Jill Francis, Wendy Hardeman, Martin P. Eccles, James Cane, and Caroline E. Wood. 2013. “The Behavior Change Technique Taxonomy (v1) of 93 Hierarchically Clustered Techniques: Building an International Consensus for the Reporting of Behavior Change Interventions.” Annals of Behavioral Medicine 46 (1): 81–95. doi:10.1007/s12160-013-9486-6.

- Michie, Susan, Maartje M. Van Stralen, and Robert West. 2011. “The Behaviour Change Wheel: A New Method for Characterising and Designing Behaviour Change Interventions.” Implementation Science 6 (1): 42. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-6-42.

- Neilsen Norman Group. 2020. Service Blueprints Definition. Accessed February 9, 2020. https://www.nngroup.com/articles/service-blueprints-definition/

- NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement. 2009. The EBD Approach: Experience Based Design Using Patient and Staff Experience to Better Healthcare Services. Tamworth: New Audience Limited. ISBN 978-1-906535-83-4.

- Niedderer, Kristina, Stephen Clune, and Geke Ludden, eds. 2017. Design for Behaviour Change: Theories and Practices of Designing for Change. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Norman, Donald A., and Pieter Jan Stappers. 2015. “DesignX: complex Sociotechnical Systems.” She Ji: The Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation 1 (2): 83–106. doi:10.1016/j.sheji.2016.01.002.

- O’Malley, Lucy, Rachael Powell, Sharon Hulme, Matthew Lievesley, Wendy Westoby, Jess Zadik, Audrey Bowen, Paul Brocklehurst, and Craig J. Smith. 2020. “A Qualitative Exploration of Oral Health Care among Stroke Survivors Living in the Community.” Health Expectations 23 (5): 1086–1095. doi:10.1111/hex.13074.

- Point of Care Foundation. 2020. EBCD: Experience-Based Co-Design Toolkit – Step-by-Step Guide. Accessed March 29, 2020. https://www.pointofcarefoundation.org.uk/resource/experience-based-co-design-ebcd-toolkit/

- Ramos, Mayara, Simon Bowen, Peter C. Wright, Marcelo Gitirana Gomes Ferreira, and Fernando Antônio Forcellini. 2020. “Experience Based co-Design in Healthcare Services: An Analysis of Projects Barriers and Enablers.” Design for Health 4 (3): 276–295. doi:10.1080/24735132.2020.1837508.

- Reay, Stephen D., Guy Collier, Reid Douglas, Nick Hayes, Ivana Nakarada-Kordic, Anil Nair, and Justin Kennedy-Good. 2017. “Prototyping Collaborative Relationships between Design and Healthcare Experts: Mapping the Patient Journey.” Design for Health 1 (1): 65–79. doi:10.1080/24735132.2017.1294845.

- Robert, Glenn. 2013. “Participatory Action Research: Using Experience-Based Co-design to Improve the Quality of Healthcare Services.” In Understanding and Using Health Experiences–Improving Patient Care. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Robert, Glenn, and Alastair S. Macdonald. 2017. “Co-Design, Organisational Creativity and Quality Improvement in the Healthcare Sector: ‘Designerly’ or ‘Design-like’.” In Designing for Service. Vol. 9, 117–130. London: Bloomsbury.

- Salmon, Victoria E., Sarah Hewlett, Nicola E. Walsh, John R. Kirwan, Maria Morris, Marie Urban, and Fiona Cramp. 2019. “Developing a Group Intervention to Manage Fatigue in Rheumatoid Arthritis through Modifying Physical Activity.” BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 20 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1186/s12891-019-2558-4.

- Sanders, E. B. N., and P. J. Stappers. 2008. “Co-creation and the New Landscapes of Design.” CoDesign 4 (1): 5–18. doi:10.1080/15710880701875068.

- Steen, Marc, Menno Manschot, and Nicole De Koning. 2011. “Benefits of co-Design in Service Design Projects.” International Journal of Design 5 (2): 53–60.

- Stroke Association. 2018. Stroke. State of the Nation: Statistics February 2018. https://www.healthwatchnortheastlincolnshire.co.uk/news/state-nation-stroke-statistics

- Talbot, Ana, Marian Brady, Denise L. C. Furlanetto, Heather Frenkel, and Brian O. Williams. 2005. “Oral Care and Stroke Units.” Gerodontology 22 (2): 77–83. doi:10.1111/j.1741-2358.2005.00049.x.

- Visser, Froukje Sleeswijk, Pieter Jan Stappers, Remko Van der Lugt, and Elizabeth B. N. Sanders. 2005. “Context Mapping: Experiences from Practice.” CoDesign 1 (2): 119–149. doi:10.1080/15710880500135987.

- Wensveen, Stephan, and Ben Matthews. 2015. “Prototypes and Prototyping in Design Research.” In The Routledge Companion to Design Research, 262–276. Taylor & Francis. doi:10.4324/9781315758466.

- White, D. A., G. Tsakos, N. B. Pitts, E. Fuller, G. V. A. Douglas, J. J. Murray, and J. G. Steele. 2012. “Adult Dental Health Survey 2009: Common Oral Health Conditions and Their Impact on the Population.” British Dental Journal 213 (11): 567–572. doi:10.1038/sj.bdj.2012.1088.