ABSTRACT

Background: First-person digital narratives are short videos produced independently by or in partnership with the person to tell their personal experience.

Objectives: The objective of this study was to describe how first-person digital narratives of adults with non-cancer pain are represented on YouTube. A secondary aim was to analyze first-person digital narratives hosted on pain management websites of professional organizations to explore whether these videos represented chronic pain with the same content.

Method: Guided by the methodological framework of Arksey and O’Malley, a conventional content analysis was undertaken analyzing the chronic pain videos published on YouTube and six global pain management websites.

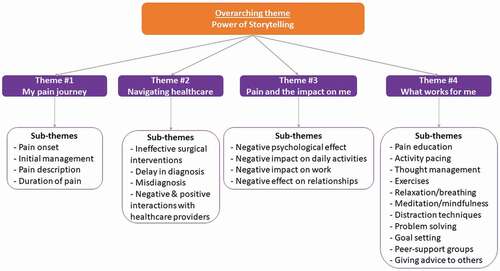

Results: Of the 78 videos (54 YouTube and 24 pain websites) that were analyzed, the overarching theme “power of storytelling” suggests that personal stories were used as a medium to share lived experiences of chronic pain, providing help and advice to similar others. The four supporting themes were (1) My pain journey, (2) Navigating health care, (3) Pain and the impact on me, and (4) What works for me. There was no major difference in subthemes between the YouTube and pain website videos.

Conclusion: Digital narratives enable those living with chronic pain to voice their experiences and communicate their pain journeys and may thus provide a sense of validation. Digital narratives can be used as a therapeutic tool to provide insights for others into the lived experience of chronic pain and to provide peer support for people with pain. Future studies are needed to investigate the clinical effectiveness and implementation of digital stories in chronic pain management.

RÉSUMÉ

Contexte: Les récits numériques à la première personne sont de courtes vidéos produites de manière indépendante par la personne ou en partenariat avec elle pour raconter son expérience personnelle.

Objectifs: L’objectif de cette étude était de décrire comment les récits numériques à la première personne d’adultes souffrant de douleur non cancéreuse sont représentés sur You Tube. Un objectif secondaire était d’analyser les récits numériques à la première personne hébergés sur des sites Web de prise en charge de la douleur d’organisations professionnelles afin de déterminer si ces vidéos représentaient la douleur chronique avec le même contenu.

Méthode: À partir du cadre méthodologique d’Arksey et O’Malley, une analyse de contenu conventionnelle a été entreprise pour analyser des vidéos sur la douleur chronique publiées sur YouTube et sur six sites Web de prise en charge de la douleur.

Résultats: Sur les 78 vidéos (54 sur YouTube et 24 sur des sites Web sur la douleur) qui ont été analysées, le thème « le pouvoir du récit » porte à croire que les histoires personnelles ont été utilisées comme moyen de partager des expériences de douleur chronique vécues, en plus d’apporter de l’aide et de donner des conseils à d’autres personnes dans la même situation. Les quatre thèmes étaient (1) Mon parcours avec la douleur, (2) Naviguer au sein des soins de santé, (3) La douleur et son impact sur moi, et (4) Ce qui fonctionne pour moi. Il n’y avait pas de grande différence dans les sous-thèmes entre les vidéos diffusées sur You Tube et celles qui étaient diffusées sur des sites Web portant sur la douleur.

Conclusion: Les récits numériques permettent aux personnes vivant avec une douleur chronique d’exprimer leurs expériences et de communiquer leurs parcours avec la douleur, pouvant ainsi donner un sentiment de validation. Les récits numériques peuvent être utilisés comme un outil thérapeutique pour donner aux autres un aperçu de l’expérience de la douleur chronique et offrir du soutien par les pairs aux personnes souffrant de douleur. Des études futures sont nécessaires pour étudier la mise en œuvre et l’efficacité clinique des récits numériques dans la prise en charge de la douleur chronique.

Introduction

Chronic non-cancer pain in adults is a significant global health burdenCitation1 and is defined as pain that lasts or recurs for more than three months.Citation2 Chronic non-cancer pain carries significant personal and economic costs, including work productivity loss, early retirement, and decreased quality of life.Citation3 The causes of chronic pain are multifactorial and are frequently misunderstood by both health practitioners and the public.Citation4 Furthermore, due to the often invisible nature of the condition, people living with chronic pain can be marginalized by society and clinicians and their realities minimized.Citation5 This in turn leads to further psychological distress and poor health outcomes, including sleep disturbance, depression, and suicidal ideation.Citation6

Illness narratives are “… a story the patient tells, and significant others retell, to give coherence to the distinctive events and long-term course of suffering.”Citation7(p49) Illness narratives can help promote behavior change by increasing social skills, self-awareness and self-reflection.Citation7 The activity of creating a narrative can also act as a healing process, promoting personal contemplation and emotional acceptance.Citation8 An online field experiment that explored the impact of shared illness narratives on the working lives of 166 people with chronic inflammatory bowel disease found that personal relevance enabled the reader to connect with the storyteller, increasing motivation and perceived ability to work.Citation9 These findings suggest that having platforms for people to communicate the experience of living with chronic pain may, in addition to providing a therapeutic intervention,Citation8 improve public knowledge and awareness.Citation10

Social media is now established as a public media space where adolescentsCitation11 and adultsCitation12 living with chronic pain are connecting to share and access illness narratives. Previous studies have shown that members of online communities can benefit from mastery experiences of others, learning through vicarious experience to engage in self-management behaviors.Citation13,Citation14 Studies examining the portrayal of illness narratives of people living with chronic pain in social media platforms like Flickr, Tumblr,Citation15 and InstagramCitation16 have identified new visual and multimodal possibilities for pain communication. Another study analyzing social representations of chronic pain in four media sources (newspapers, Pinterest, YouTube, and the movie Cake) concluded that the type of medium shapes the message.Citation17 The social media platforms (YouTube and Pinterest) provided first-person accounts, and the newspaper articles and the movie Cake, which was chosen as a case example for films, provided third-person accounts of pain.Citation17 Social media platforms like YouTube facilitate wide dissemination of illness narratives by video, providing cost-effective ways of communicating chronic pain journeys, with wide-reaching impact,Citation15 and thus the status and content of online pain narratives warrant further exploration.

A subset of illness narratives are first-person digital narratives: short videos produced independently by or in partnership with the person to tell their personal experience.Citation18 These can be a combination of short video and audio clips complemented by images, animation, and music. First-person digital narratives enable self-validation of experience and allow sharing of self-management strategies, clinical advice, and peer support.Citation11 As user-generated content, digital narratives may be of variable production quality depending on the source of content (e.g., videos from professional pain organizations). Further, the information may or may not align with recommended best clinical practices for people with chronic pain. Because first-person digital narratives may be a scalable mechanism for communicating the lived experiences of adults with chronic pain, we aimed to understand the representations of first-person digital narratives on YouTube. In addition, because health care providers commonly recommend professional pain management websites for self-management support,Citation19 we wanted to explore the differences in representations of first-person digital narratives hosted on pain management websites and YouTube.

Methods

Because online video analysis is a nascent research field, we were guided by the scoping review methodological framework of Arksey and O’MalleyCitation20 and recommendations for searching and screening YouTube videos.Citation21 The stages of the scoping review framework were adjusted for a scoping review of YouTube videos (1) to identify the research question; (2) to identify relevant videos; (3) to select videos; (4) to chart the data; and (5) to collate, summarize, and report the results. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension checklist for reporting scoping reviews was used to guide reporting of this study.Citation22

Identifying the Research Question

Two research questions were established before commencing the review: (1) How were lived experiences of adults with chronic pain represented in YouTube videos? (2) Were there differences between the representation of adults with non-cancer chronic pain video contents from pain management websites and YouTube?

Video Selection/eligibility Criteria

Videos were included if (1) the individual in the video was subjectively deemed by raters as aged 18 years or over; (2) the video primarily focused on the individual’s own experience or chronic pain story; (3) the video channel was a personal account, patient organization, professional pain organization, academic institution, or a hospital; (4) video duration greater than 1 min but less than or equal to 10 min based on the assumption that videos of shorter duration would be engaging and more likely to be used in clinical practice;Citation23 and (5) the video was in English. Videos were excluded if (1) it was on cancer-related pain; (2) it focused on acute pain; (3) it was an advertisement and/or promotion of a medical or surgical procedure or a product; or (4) it primarily captured the health care professional’s perspective.

Identifying Relevant Videos and Video Selection

The YouTube search was completed on April 22, 2020, in New Zealand using Google search in Google Chrome. Pilot searches on YouTube through Google Chrome were undertaken to refine the search terms that produced the most relevant video content. Two members of the research team (ML and TE) conducted independent searches using two search terms: “chronic pain story” and “intitle:chronic pain story.” A new YouTube account was created and browser history was cleared to ensure that previous search history did not influence search results, a recommended strategy for YouTube reviews.Citation21 Two members of the team (ML and TE) independently reviewed the title and metadata of videos for potential inclusion, in the order they were presented in the YouTube search list. Each video was then watched and the metadata were examined, both considered against inclusion criteria. Videos meeting inclusion criteria were added to a YouTube playlist (a function within YouTube to curate a collection of videos). ML and TE both created independent playlists based on the search terms. The screening of the search ceased when ten consecutive videos no longer met inclusion criteria, similar to a previous YouTube review.Citation23

A secondary search for video stories was conducted on global pain management websites that were identified in a previous review of pain management websites.Citation24 One team member (KM) screened all sections of these 27 websites for eligible videos through link descriptions such as “Stories,” “Real Stories,” or “Patient Experiences.”

Verification and Consensus

Each video playlist of included videos was watched and screened independently by the other researcher to ensure that inclusion criteria had remained consistent between both reviewers. Discrepancies were noted. Mediation with a third member (DM) was then done to assess the inclusion of the videos with discrepant decisions. All three members, through discussion and re-watching of the videos, resolved disagreements regarding a video’s eligibility for inclusion.

Charting the Data

The final sample of included YouTube videos were divided between four members (DM, LT, ML, and TE) to extract descriptive characteristics. Metadata provided by YouTube were charted on a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet and the final data set was then checked by another member of the research team (HD). Data charted for each video included title of video, URL, name of YouTube channel, duration on YouTube (days), number of likes, number of dislikes, duration (minutes), number of views, number of comments, YouTube category (category assigned by creator based on video content; e.g., education, entertainment, comedy), video source (academic/medical research institution, health care company, educational organization, professional association, individual health care professional/academic, private account, news broadcaster, animation company, or other), video style (live action: talk to camera; role-play; lecture; interview, animation: whiteboard; 2D; 3D, still images, screencast, or combination; e.g., live action and still images), and country of origin.

Collating, Summarizing, and Reporting the Results

The video contents were analyzed using a conventional content analysis approach.Citation25 To adapt this approach for video content, initially four of the included videos were randomly selected and watched by four members (DM, LT, ML, TE) independently to develop an initial content analysis framework. While watching each video, team members identified quotes that formed key concepts and then identified subthemes and themes relevant to the research question. Subsequently, a consensus meeting was held with all team members to finalize the initial coding framework by mutual consensus. The 78 videos were then split between two pairs of reviewers (DM and LT; ML and TE). Both members of each pair independently coded 39 videos by watching them multiple times and identified subthemes and themes relevant to the coding framework, backed up with supporting quotes. A consensus meeting was held among each pair to compare coding and derive consensus by discussion. Then, all team members had a consensus meeting to derive the final themes and subthemes.

Ethical Considerations

Institutional ethics approval and informed consent were deemed not necessary because we collected information from publicly available videos, similar to previous YouTube evaluation reviews in chronic pain.Citation11,Citation23 We have, however, adhered to the ethical principles recommended for Internet-mediated research by the British Psychological SocietyCitation26 and we acknowledge that the issue of considering online information as public or private is a gray area, similar to previous Internet research by Toye et al.Citation12 Although some transcribed quotes from the included videos were included as part of our content analysis, to ensure the anonymity of the analyzed videos, similar to Forgeron et al,11 the quotes were searched verbatim in the Google database. This search did not retrieve the source video. Further, we have assigned numbers for the individual videos without providing original links to the videos to limit traceability.

Results

Videos Included

The YouTube search of title and metadata identified 66 videos (), of which 12 were excluded, resulting in 54 videos. The videos were excluded because they were deemed advertisements for private health care providers (n = 10) and duplicates (n = 2). Secondary searching from six pain management websites (LivePlanBe, n = 6; mypainfeelslike, n = 4; painHEALTH, n = 10; International Association for the Study of Pain, n = 2; and PainToolKit, n = 2) identified another 24 videos, resulting in 78 videos for final content analysis (Supplementary ).

Table 1. Theme description and example quotes from videos (N = 78)

Table 2. Comparison of the relative frequency of subthemes between the YouTube and pain management website videos

Characteristics of Included Videos

Most of the included YouTube videos originated from the United States (45/54, 83%), with 28 videos posted by the U.S. Pain Foundation Inc. YouTube channel, marking the International pain awareness month in September 2019 (Supplementary ). There were nine videos uploaded by individuals from private accounts and seven videos from private health care companies (Supplementary ). The mean video duration was 4.93 min (range 1.01–9.54 min). Views ranged from 9 to 168,338, with a median of 290. Comments for videos ranged from 0 to 826, with a median of 4. The video with the most views and comments was “Fibromyalgia: Living with chronic pain—BBC stories” (Supplementary , video 1). YouTube categorized 33/54 of these videos to be educational, people and blogs (7/54) and science and technology (4/54). The videos had been posted between 79 and 2436 days before the date of search (Supplementary ).

Most of the 24 videos found on the secondary search of pain management websites originated from three countries: Australia (n = 10), Canada (n = 6), and the UK (n = 5). The mean video duration was 4.25 min (range 2.49–6.09 min). Views ranged from 176 to 55,091,815 with a median of 822. Comments for videos ranged from 0 to 33,803. The video with the most views and comments was “Never, Ever Give Up. Arthur’s Inspirational Transformation” (Supplementary , video 77). YouTube categorized 9/24 of these videos as people and blogs, educational (8/24) and science and technology (1/24). The videos from LivePlanBe were not located on YouTube, so the videos were not categorized and no information on comments was accessible (Supplementary ).

Video Content Analysis: Themes

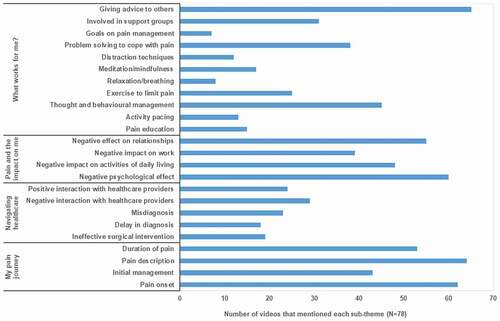

Our analysis found that “power of storytelling” was the overarching theme with four supporting themes: (1) My pain journey, (2) Navigating health care, (3) Pain and the impact on me, and (4) What works for me (). The theme and subtheme descriptions with supporting quotes are presented in and the frequency of subthemes is illustrated in . There were no major differences in subthemes derived from the YouTube videos and pain management website videos ().

Overarching Theme: Power of Storytelling

The overarching theme of “power of storytelling” suggests that personal stories were used as a tool to share lived experiences of chronic pain, to provide help, advice, and support to similar others. The stories conveyed the journey of living with pain, challenges of navigating health care, the psychosocial impact of pain on the person, and the importance of finding pain management strategies that worked for them.

My Pain Journey

This theme encompassed personal experiences of chronic pain, including descriptions relating to the onset of pain (62/78, 79%), duration of symptoms (53/78, 68%), location of pain, and descriptions of their symptoms (e.g., severity and nature of pain; 64/78, 82%). Personal experiences from initial management of their symptoms via medications, exercises, and surgical interventions were also narrated (43/78, 55%; ).

Navigating Health Care

This theme captured the challenges of navigating health care. Delays in receiving a diagnosis and both positive and challenging interactions with health professionals were portrayed. Delayed diagnosis covered how people described the often lengthy process before receiving a definitive diagnosis for the cause of their chronic pain (18/78, 23%). Stories of failed medical and surgical interventions that worsened symptoms or were ineffective and thus contributed to the chronicity of symptoms (19/78, 24%) and receiving inaccurate diagnoses from health care providers (23/78, 29%) were also shared ().

Examples of both positive (24/78, 31%) and negative health care professional experiences (29/78, 37%) were captured. People identified negative interactions such as feeling ignored or being mistreated by health care professionals in their search for a working treatment or answers for their pain. They reported a lack of compassion and understanding from health care professionals when they failed to receive individualized, person-centered care and felt disappointed when they were offered generalized and ineffective alternatives such as stand-alone pain medications. Positive interactions were narrated when they felt that they were listened to by health care providers who took an interest in wanting to help solve the complex problems associated with their chronic pain. Those professionals understood that the person was not just their pain and often took a holistic mind–body approach to pain management. People also emphasized that these health professionals were refreshingly honest in saying what they can and cannot do, which took the burden of uncertainty off them ().

Pain and the Impact on Me

This theme captured how people describe the complex impact of chronic pain on their lives. Psychological impacts covered how people often described the cognitive and emotional burden of chronic pain, expressed in the form of dealing with depression, frustration, and anxiety (60/78, 77%). Participants expressed the impact of pain on activities of daily living and discussed how basic functional movements were made too difficult or painful to complete leading to a loss of independence (50/78, 64%). People shared stories of lost jobs or having to stop working due to their pain, leading to financial complications and distress (41/78, 53%). People also frequently discussed the social impact of living with chronic pain in the form of difficulty maintaining healthy relationships with friends and family and the social isolation and strain that resulted in (55/78, 71%; ).

What Works for Me

This theme captured the beneficial skills and strategies adopted by people living with chronic pain. People described building self-efficacy through skill utilization such as learning about pain physiology (15/78, 19%), activity pacing (13/78, 17%), becoming accepting of their pain via thought and behavior management (45/78, 58%), benefits of exercise (25/78, 32%), relaxation/breathing control (8/78, 10%), meditation and mindfulness (17/78, 22%), distraction techniques (12/78, 15%), and goal setting (7/78, 9%). Problem-solving and adapting coping strategies when faced with flare-ups (38/78, 49%) were also discussed. Many participants provided this information in form of advice to the viewers (65/78, 83%). Finally, this theme also recognized the benefits of joining community groups (31/78, 40%) and forming relationships with similar others as a way of advocating and validating their condition ().

Comparison of YouTube and Pain Management Website Videos

There was no major difference in the frequency of subthemes between YouTube and pain website videos (). For the theme “what works for me” there was a more frequent occurrence of subthemes focusing on self-management strategies in videos hosted in pain management websites compared to YouTube ().

Discussion

The primary purpose of this study was to explore how lived experiences of chronic pain are represented online as a way of understanding first-person digital narratives. The overarching theme of the “power of storytelling” suggests that personal digital stories were used as a tool to share lived experiences of chronic pain, often with the intent to provide help, advice, and support to similar others. The stories conveyed the journey of living with pain, challenges of navigating health care, and psychosocial impact on the person and their social relationships. People living with chronic pain described their journey through discovering successful self-management strategies that worked for them and emphasized the importance of finding support services.

Our results suggest that sharing personal pain stories via short videos may be an accessible and engaging tool to improve self-efficacy through vicarious experiences of listening to similar others. Pain self-efficacy is the confidence in one’s ability to engage in valued activities despite painCitation27 and is one of the key outcomes to predict long-term positive functional outcomes in people living with pain.Citation28 Self-efficacy can be fostered via mastery experience, vicarious experience, verbal persuasion, and psychological factors (e.g., emotions and beliefs).Citation29 The social ecological theory acknowledges the influence of the social environment on health behaviorCitation30 and may be a relevant theory for understanding these pain experience narratives. It is plausible that if positive experiences of pain self-management strategies are shared through a community-based platform (YouTube), people with chronic pain may be more inclined to try the shared strategies and thus reinforce their ongoing self-management. However, the influence of such digital stories on improving self-efficacy and fostering health behaviors requires further research.

These results suggest YouTube as a viable platform that provides people living with chronic pain the ability to share their stories and the opportunity to communicate their lived experiences as a way of social validation to their often invisible condition. Through these videos, people were able to explain their pain and articulate descriptive characteristics unique to their condition. The previous synthesis of qualitative studies aiming to explore patient experiences of chronic nonmalignant musculoskeletal pain have alluded to the difficulty for patients to construct an explanation for their suffering and the struggle to explain the pain that does not fit an objective biomedical category.Citation31 Thus, the dissemination of digital stories through social media platforms like YouTube has the potential to be an effective tool for pain communication.Citation12 The process of creating digital stories and giving individuals the opportunity to describe their own experience in this form has been shown to produce positive feelings and a sense of control for the storyteller and their health.Citation32 The process of sharing, constructing, and listening to similar others through stories elicits feelings of empowerment and empathy and strengthens social connection.Citation32

People shared their experiences of navigating the health care system and how interactions with health care professionals impacted their pain journey. Similar to the findings from a recent evaluation of news media stories representing chronic pain in New Zealand,Citation33 people mainly shared challenging experiences in navigating the health care system. These were related to expressing the impact of failed pharmacological and surgical treatments, which highlights the consequences of “low-value” care where harms outweigh the benefits.Citation34 A global call for health professionals has been made to reduce “low-value” care and adopt an active self-management approach through nonpharmacological treatments (e.g., education, exercise, and cognitive treatments) as a primary intervention for chronic pain management.Citation35 This approach also acknowledges the need to address misconceptions about the causes, prognosis, and effectiveness of different treatments in the population and among health care providers. Our findings in this medium suggest that these recommendations are not being met, because narrators reported that nonpharmacological treatments were only offered after failed pharmacological and surgical treatments.

Our findings of digital stories used as a medium for pain self-expression and voicing of multifaceted burden concur with previous studies evaluating the portrayal of chronic pain in social mediaCitation15–17 and news media.Citation33 The holistic burden placed on individuals suffering from chronic pain affects all aspects of their lives, not just the physical. People frequently referred to the psycho-emotional, social, and psychological impacts of living with ongoing pain, making them increasingly difficult to express and validate to others, including health care professionals.Citation31 Creating digital narratives provides an audio-visual representation of such holistic burdens and lets an individual express them in a way that resonates with their experience.Citation17

We identified an expression of a perceived lack of compassion and understanding about holistic burdens from health care professionals in clinical encounters. The benefits of having mutual respect and a therapeutic alliance between health care providers and patients with chronic pain are well reported.Citation36 The complexities of the therapeutic alliance between patients with chronic pain and health care providers were explored in a metasynthesis.Citation37 This qualitative systematic review examined the perceived enablers and barriers to ongoing self-management that health care providers can foster through nonjudgmental communication, empathetic listening, and adopting holistic person-centered care.Citation37 By contrast, poor patient–clinician relationships were reported when the person felt ignored or not listened to or believed and received conflicting information from health care professionals.Citation37 This reinforces that people with chronic pain need to be heard and acknowledged by the health care professionals whom they are seeking validation from. Health care professionals have the opportunity to use these digital narratives to gain deeper insights, build relationships centered on respect and understanding, promote therapeutic alliance, and foster self-management.Citation31

Although YouTube is a popular platform for sharing videos, there are several caveats when searching for health information and patients’ stories. Firstly, because it is a public domain, anyone can disseminate health information and there is no monitoring of the video content accuracy unless it breaches the platform’s code of conduct. This can lead to inaccurate health misinformation being easily shared.Citation38 Another observation from our review was the pervasive presence of advertising on YouTube, an open-source, commercial platform. Many videos found in the initial searches were produced by for-profit health care companies and may therefore contain information to support their commercial interests.Citation39 For example, many videos that were excluded from our review had titles suggesting that they were simply a patient sharing their story; however, those videos were edited advertisements promoting books and commercial surgical devices. Despite these caveats, the increased presence of professional pain advocacy groups (e.g., International Association for the Study of Pain) and patient-led initiatives (e.g., PainToolkit) providing global pain education and offering comprehensive playlists to educate self-management support is promising.

Our review findings have insights for future research. As video stories is an emerging area in chronic pain research, future studies focusing on understanding patient perspectives of accessing and making sense of video stories may provide deeper perspectives of these online health resources in fostering pain self-management support. Another recommendation for ethnographic studies capturing the experiences of patient-produced videos with pain clinicians could gain insights on an empathetic understanding of pain clinicians. Future research should also capture video stories of people with chronic pain from non-Western countries, because most of the included videos were from the United States, Australia, Canada, and the UK.

Strengths and Limitations

Although we followed the recommendations in conducting reviews on YouTube,Citation21 we acknowledge the following methodological limitations. Firstly, the patient stories in the videos examined were not necessarily generated for the primary purpose of describing one’s illness narrative. Future studies specifically eliciting one’s illness narrative could provide deeper insights into living with chronic pain. Next, videos were included if they were English and less than 10 min in duration. Though the majority of existing videos fit these criteria, we were unsure how the excluded videos could have impacted our study findings. Secondly, due to our specific inclusion criteria, our search results may not have mimicked an average user’s search strategy. The key search term “intitle: chronic pain story” is highly specific and presented 28% more eligible videos than the search term “chronic pain story.” Though including this term strengthened the evaluation, it is unlikely that someone would have used this technique to find videos. People are likely to search regarding their condition (e.g., back pain, fibromyalgia), so future research could consider condition-specific terms. Most people from the included videos indicated not yet having a definitive diagnosis, so utilizing the umbrella term of “chronic pain story” includes those at all stages of their pain journey. Thirdly, YouTube employs a title-based search strategy. Though this is useful for specific video searches, YouTube cannot analyze video content in the way a Google search would for text-based resources. Therefore, our search would have missed videos on chronic pain that did not have the term explicitly in the title. This became evident when “Never, Ever Give Up. Arthur’s Inspirational Transformation,”Citation40 sourced from the Pain Toolkit website, had 55 million views yet was not discovered in the primary YouTube search. Lastly, videos were selected as they presented from most to least relevant. This aided the reproducibility of the search but may have narrowed the number of videos found compared to finding videos through the snowball effect.

Clinical Implications

Our study has several clinical implications. Firstly, digital stories are not only beneficial to the curator but may also act as a useful therapeutic tool for educating others. The videos often consisted of helpful self-management strategies and advice to others. Current and future health professionals could use these videos to enhance empathy by understanding people’s frustration and the significance of living with chronic pain. Clinically, this also presents an opportunity to incorporate tailored videos as a cost-effective adjunct to face-to-face treatment.Citation24 Reinforcing self-management strategies through vicarious experience may further support someone with chronic pain. Secondly, YouTube videos provide holistic information focused on navigating health care, whereas videos from pain management websites tended to refer to specific self-management strategies. Clinicians need to be cognizant of this difference when referring patients to these resources. From a health literacy perspective, most pain websites curated written resources to complement videos, thus providing learners with multimodal educational opportunities. Both YouTube and pain websites are accessible and engaging, but some may perceive pain management websites as a more reliable source of information.Citation24 Lastly, the sense of catharsis and community when participating in digital storytelling as part of a group-based pain management program was alluded to in our findings. Being acknowledged by a wider, more culturally diverse group of people going through similar situations acts to empower the individual and could be integrated into routine pain management programmes.

Conclusions

Through the power of storytelling, first-person digital stories take viewers on an individual’s journey through the struggles and challenges faced by people living with chronic pain. YouTube and pain management websites provide a public platform to vocalize people’s pain journeys, highlight the struggles of navigating health care, and discuss the holistic burdens that chronic pain creates. This medium can be utilized as an educational tool for the public, people living with pain, and health care providers to gain access to the lived experiences of people living with chronic pain. Future studies are needed to investigate the effectiveness and impact of digital stories to improve clinical outcomes in people with pain and the potential for integrating digital stories in clinical practice by health care providers.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (218.7 KB)Acknowledgments

We thank Michael Fauchelle, liaison librarian from the University of Otago, Wellington, New Zealand, for assisting with our initial search strategy.

Disclosure Statement

Hemakumar Devan has not declared any conflicts of interest. Toa Elphick-laveta has not declared any conflicts of interest. Maxwell Lynch has not declared any conflicts of interest. Katie MacDonell has not declared any conflicts of interest. David Marshall has not declared any conflicts of interest. Leah Tuhi has not declared any conflicts of interest. Rebecca Grainger has not declared any conflicts of interest.

Data Availability Statement

All raw data on coding are available from the corresponding author up on request.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Blyth FM, Briggs AM, Schneider CH, Hoy DG, March LM. The global burden of musculoskeletal pain—where to from here? Am J Public Health. 2019;109(1):35–40. doi:https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2018.304747.

- Treede R-D, Rief W, Barke A, Aziz Q, Bennett MI, Benoliel R, Cohen M, Evers S, Finnerup NB, First MB, et al. Chronic pain as a symptom or a disease: the IASP classification of chronic pain for the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11). Pain. 2019;160(1):19–27. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001384.

- Clark S, Horton R. Low back pain: a major global challenge. Lancet. 2018;391(10137):2302. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30725-6.

- Toye F, Seers K, Allcock N, Briggs M, Carr E, Andrews J, Barker K. Patients’ experiences of chronic non-malignant musculoskeletal pain: a qualitative systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2013;63(617):e829. doi:https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp13X675412.

- Cohen M, Quintner J, Buchanan D, Nielsen M, Guy L. Stigmatization of patients with chronic pain: the extinction of empathy. Pain Med. 2011;12(11):1637–43. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01264.x.

- Racine M. Chronic pain and suicide risk: a comprehensive review. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatr. 2018;87:269–80. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2017.08.020.

- Kleinman A. The illness narratives: suffering, healing, and the human condition. New York; 1988.

- Briant KJ, Halter A, Marchello N, Escareño M, Thompson B. The power of digital storytelling as a culturally relevant health promotion tool. Health Promot Pract. 2016;17:793–801. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839916658023.

- Brokerhof IM, Ybema JF, Bal PM, Soundy A. Illness narratives and chronic patients’ sustainable employability: the impact of positive work stories. PLoS One. 2020;15(2):e0228581. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0228581.

- Lipsey AF, Waterman AD, Wood EH, Balliet W. Evaluation of first-person storytelling on changing health-related attitudes, knowledge, behaviors, and outcomes: a scoping review. Patient Educ Couns. 2020;103(10):1922–34. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2020.04.014.

- Forgeron PA, McKenzie E, O’Reilly J, Rudnicki E, Caes L. Support for My Video is support for me. Clin J Pain. 2019;35(5):443–50. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/AJP.0000000000000693.

- Toye F, Seers K, Barker K. “It’s like she’s talking about me”—Exploring the value and potential impact of a YouTube film presenting a qualitative evidence synthesis about chronic pain: an analysis of online comments. Can J Pain. 2020;4:61–70. doi:https://doi.org/10.1180/24740527.2020.1785853.

- Merolli M, Gray K, Martin-Sanchez F. Therapeutic affordances of social media: emergent themes from a global online survey of people with chronic pain. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(12):e284. doi:https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.3494.

- Gasteiger N, Grainger R, Day K. Arthritis-related support in a social media group for quilting hobbyists: qualitative study. Interact J Med Res. 2018;7:e11026. doi:https://doi.org/10.2196/11026.

- Gonzalez-Polledo E, Tarr J. The thing about pain: the remaking of illness narratives in chronic pain expressions on social media. New Media & Society. 2016;18:1455–72. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444814560126.

- Sendra A, Farré J. Communicating the experience of chronic pain through social media: patients’ narrative practices on Instagram. J Health Commun. 2020;13(1):46–54. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17538068.2020.1752982.

- Kugelmann R, Watson K, Frisby G. Social representations of chronic pain in newspapers, online media, and film. Pain. 2019;160:298–306. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001422.

- Fiddian-Green A, Kim S, Gubrium AC, Larkey LK, Peterson JC. Restor(y)ing health: a conceptual model of the effects of digital storytelling. Health Promot Pract. 2019;20(4):502–12. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839918825130.

- Devan H, Godfrey HK, Perry MA, Hempel D, Saipe B, Hale L, Grainger R. Current practices of health care providers in recommending online resources for chronic pain self-management. J Pain Res. 2019;12:2457. doi:https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S206539.

- Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8:19–32. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616.

- Sampson M, Cumber J, Li C, Pound CM, Fuller A, Harrison D. A systematic review of methods for studying consumer health YouTube videos, with implications for systematic reviews. Peer J. 2013;1:e147. doi:https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.147.

- Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, Moher D, Peters MDJ, Horsley T, Weeks L, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Int Med. 2018;169(7):467–73. doi:https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850.

- Heathcote LC, Pate JW, Park AL, Leake HB, Moseley GL, Kronman CA, Fischer M, Timmers I, Simons LE. Pain neuroscience education on YouTube. Peer J. 2019;7:e6603–e6603. doi:https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.6603.

- Devan H, Perry MA, van Hattem A, Thurlow G, Shepherd S, Muchemwa C, Grainger R. Do pain management websites foster self-management support for people with persistent pain? A scoping review. Patient Educ Couns. 2019;102(9):1590–601. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2019.04.009.

- Hsieh H-F, Shannon S. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–88. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687.

- British Psychological Society. Ethics guidelines for internet-mediated research; 2017 [accessed 2020 Nov 23]. www.bps.org.uk/publications/policy-and-guidelines/research-guidelines-policy-documents/researchguidelines-poli.

- Nicholas MK, Blyth FM. Are self-management strategies effective in chronic pain treatment? Pain Manag. 2016;6:75–88. doi:https://doi.org/10.2217/pmt.15.57.

- Lorig KR, Holman HR. Self-management education: history, definition, outcomes, and mechanisms. Ann Behav Med. 2003;26:1–7. doi:https://doi.org/10.1207/S15324796ABM2601_01.

- Bandura A, Freeman W, Lightsey R. Self-efficacy: the exercise of control. Springer; 1999.

- Glanz K, Bishop DB. The role of behavioral science theory in development and implementation of public health interventions. Ann Rev Public Health. 2010;31:399–418. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.012809.103604.

- Toye F, Jenkins S. ‘It makes you think’ - exploring the impact of qualitative films on pain clinicians. Br J Pain. 2015;9:65–69. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/2049463714549776.

- DiFulvio GT, Gubrium AC, Fiddian-Green A, Lowe SE, Del Toro-Mejias LM. Digital storytelling as a narrative health promotion process: evaluation of a pilot study. Int Q Community Health Educ. 2016;36:157–64. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0272684X16647359.

- Devan H, Young J, Avery C, Elder L, Khasyanova Y, Manning D, Scrimgeour M, Grainger R. Media representation of chronic pain in Aotearoa New Zealand – a content analysis of news media. N Z Med J. 2020;133:1–19.

- Buchbinder R, van Tulder M, Öberg B, Costa LM, Woolf A, Schoene M, Croft P, Buchbinder R, Hartvigsen J, Cherkin D, et al. Low back pain: a call for action. Lancet. 2018;391(10137):2384–88. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30488-4.

- Lin I, Wiles L, Waller R, Goucke R, Nagree Y, Gibberd M, Straker L, Maher CG, O’Sullivan PPB. What does best practice care for musculoskeletal pain look like? Eleven consistent recommendations from high-quality clinical practice guidelines: systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54(2):79–86. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2018-099878.

- Toye F, Seers K, Barker KL. Meta-ethnography to understand healthcare professionals’ experience of treating adults with chronic non-malignant pain. BMJ Open. 2017;7(12):e018411. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018411.

- Devan H, Hale L, Hempel D, Saipe B, Perry MA. What works and does not work in a self-management intervention for people with chronic pain? Qualitative systematic review and meta-synthesis. Phys Ther. 2018;98(5):381–97. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/pzy029.

- Li HO, Bailey A, Huynh D, Chan J. YouTube as a source of information on COVID-19: a pandemic of misinformation? BMJ Global Health. 2020;5(5):e002604. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002604.

- Betschart P, Pratsinis M, Müllhaupt G, Rechner R, Herrmann TR, Gratzke C, Schmid H-P, Zumstein V, Abt D. Information on surgical treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia on YouTube is highly biased and misleading. BJU Int. 2020;125(4):595–601. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/bju.14971.

- Yoga D. Never, ever give up. Arthur’s inspirational transformation. YouTube; 2012.