Abstract

Although only 5–10% of patients with asthma have severe disease, they account for a disproportionate share of the overall disease burden. Severe asthma is responsible for approximately 50% of all direct asthma-related costs as well as a significant decline in patient quality of life. For such patients, biologic or targeted therapies may be highly effective. However, their role is not widely understood and their use is currently minimal. Both Canadian and international research suggests that the adverse effects of oral corticosteroids in severe asthma are significant and costly but under-recognized. Our review of management of severe asthma in Canada highlights the need for increased recognition of the adverse effects of oral corticosteroids and more awareness of the newer alternative therapies on the part of physicians, as well as access to specialized care for the population with severe asthma including patient education resources, and ongoing monitoring with a severe asthma registry.

Résumé

Bien que seulement 5 % à 10 % des patients asthmatiques soient gravement atteints, ils représentent une part disproportionnée du fardeau de la maladie. L'asthme sévère est responsable d'environ 50 % de tous les coûts directs liés à l'asthme, ainsi que d'une diminution importante de la qualité de vie des patients. Pour ces patients, les thérapies biologiques ou ciblées peuvent être très efficaces. Cependant, leur rôle n'est pas bien compris et leur utilisation à l’heure actuelle est minime. La recherche canadienne et internationale donne à penser que les effets indésirables des corticostéroïdes oraux chez les patients souffrant d'asthme sévère sont importants et coûteux, mais insuffisamment reconnus. Notre examen de la prise en charge de l'asthme sévère au Canada met en évidence la nécessité d'une reconnaissance accrue des effets indésirables des corticostéroïdes oraux et d'une plus grande sensibilisation des médecins aux thérapies de rechange plus récentes. Il révèle aussi la nécessité que la population souffrant d'asthme sévère ait accès à des soins spécialisés, y compris à des ressources éducatives destinées aux patients, et qu’une surveillance continue soit effectuée à l’aide d’un registre de l'asthme sévère.

Introduction

Late in the 20th century, bronchodilator-driven management of asthma gave way to early use of safe and effective anti-inflammatory therapy.Citation 1 The widespread use of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), alone or combined with long-acting beta-2 agonists (LABAs), has been accompanied by substantial declines in asthma morbidity and mortality in Canada, as well as internationally.Citation 2 , Citation 3 Despite these improvements in treatment, surveys of patient outcomes show that up to half of all patients fail to achieve control of their disease.Citation 4 Treatment failure may be attributed to poor patient adherence, mishandling of inhalers, or other factors that prevent inhalation of sufficient controller therapy. The resulting breakthrough exacerbations are routinely handled by administration of short courses (or “bursts”) of prednisone.Citation 5 Although many breakthrough episodes could be prevented by more diligent use of effective inhaled therapy, a subset of patients is wholly or partly refractory to inhaled therapy. These patients have severe asthma that requires systemic therapy, typically corticosteroids. Patients with severe asthma represent approximately 5–10% of all patients with the disease but account for a disproportionate share of the overall disease burden.Citation 6 Such figures must remain approximate given the inability to distinguish “difficult-to-treat” asthma from severe asthma using epidemiologic tools. Severe asthma is responsible for approximately 50% of all direct asthma-related costs and a significant decline in patient quality of life.Citation 7 For such patients, biologic or targeted therapies may offer an effective treatment option.Citation 8 Although one biologic therapy has been recognized in the Canadian asthma guidelines for more than a decadeCitation 9 and four biologic therapies have been approved by Health Canada, the role of these agents in the treatment algorithm for asthma is not widely understood and their use remains minimal.

Methods

This review discusses the underutilization of biologic therapy in treating severe asthma and recommends steps that may be helpful in the appropriate assimilation of these therapies into clinical practice. The narrative review relied for context on a Pubmed search from 2005 to February 2019 using the search terms “severe asthma,” “monoclonal antibody,” “omalizumab,” “mepolizumab,” “reslizumab,” “benralizumab,” “lebrikizumab,” “tralokinumab,” “dupilumab,” “tezepelumab,” “interleukin-5,” “interleukin-4,” “interleukin-13,” “immunoglobulin E,” “biomarker” and “registry.” Additionally, in the near absence of severe asthma data specific to Canada, we have incorporated the results of a small practice assessment completed by Canadian specialists treating patients with severe asthma, in which severe asthma was compared to poorly controlled asthma.

Definitions and overview

Severe asthma is defined by the Canadian Thoracic Society as asthma that requires treatment with high-dose ICS and either a second controller for the previous year or systemic corticosteroids for 50% of the previous year to either prevent the asthma from being uncontrolled or for asthma that is uncontrolled despite such therapy. In this context, control is defined as minimal symptoms, infrequent exacerbations requiring steroids, no hospitalizations because of asthma, and minimal airflow limitation.Citation 6 Poor control is one component of the criteria for identifying severe asthma; however, it is not a necessary criterion. Individuals may have severe but well-controlled asthma if, for example, adequate control is maintained at the cost of daily oral steroid therapy in addition to optimal inhaled therapy. Alternatively, a patient may have moderate asthma that is poorly controlled because he or she is non-compliant with low-dose ICS that could prevent frequent symptoms and exacerbations.

Clinical complexity is added when alternative diagnoses or comorbidities are considered as an explanation for a patient’s symptoms or as contributing to poor control. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hyperventilation syndrome and panic attacks, congestive heart failure, pulmonary embolism, laryngeal dysfunction, mechanical obstruction of the airways (benign and malignant tumors), pulmonary infiltrates with eosinophilia, diffuse parenchymal lung disease, cough secondary to pharmacological agents (angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors) and vocal cord dysfunction may all present with symptoms that are similar to asthma or worsen control of the disease.Citation 8 This complexity might be expected to result in referral of patients with severe and uncontrolled asthma to specialist care, but this appears to happen infrequently. Husereau and colleagues identified a population of patients in Ontario who appeared to meet the definition of severe asthma and in whom high-dose ICS/LABAs were used to treat their disease.Citation 10 Although these patients visited their primary care physicians more than seven times on average during one year of follow-up, only 9% were referred for specialist care. Anecdotally, it appears that one reason for this lack of referral of patients with severe asthma to specialized centers may be lack of awareness that additional treatment options, including biologic or targeted therapies, are available for this small subset of patients. Moreover, primary care physicians may underestimate the severity and control of their patients’ asthma if urgent care is provided by other practitioners in various care settings, including emergency departments and walk-in clinics.

Patient perspective

Researchers are now starting to appreciate the hidden burden of severe asthma.Citation 11 A Canadian perspective was gleaned from a recent survey of patient-perceived burden of severe asthma commissioned by Asthma Canada. This research included in depth, one-on-one interviews with 24 patients as well as a quantitative online survey of 200 patients with asthma in four urban centers in three provinces.Citation 12 Patients were assessed for severe asthma (as per the Canadian consensus guidelines). More than 80% of respondents felt that their asthma was not well-controlled, reporting frequent symptoms and exacerbations. These patients were often diagnosed by their health care providers as having less severe disease, despite an objective assessment of severe asthma: 48% reported a diagnosis of mild, moderate, or “moderately severe” asthma. Most patients with severe asthma were managed by their family physicians, although many felt that a specialist would provide better care. More than 1 in 5 patients reported that they had access to a certified respiratory educator (CRE). Only half of the patients in the survey reported having had lung function or pulmonary testing prior to diagnosis. The survey also found that communication between the primary care provider and the patient regarding management of their asthma was poor and, in particular, patients were rarely informed about new medications and treatment options. The cost of medication and lack of insurance coverage were also found to be major barriers to treatment. Overall, patient quality of life was severely affected by asthma, creating social barriers, reducing activity levels, and contributing to lost productivity for both patients and their families.

To gain a better understanding of the burden of severe asthma from the perspective of the Canadian specialist caring for patients with asthma, and as a complement to the Canadian asthma patient survey, a national practice assessment was undertaken that included 10 clinicians, each of whom were required to assess 4 patients (for a total of 40 patients). The reflective exercise was administered via a Web-based portal and included three components: a practice profile/physician demographic questionnaire (completed once only), a practice assessment (review of diagnostic testing, monitoring of control, and therapeutics) including 4 patients with severe asthma completed during or soon after an office visit, and a series of reflective questions completed by the physician after the final patient assessment (Bridge Medical Communications, data on file). The assessment ran for approximately one month (December 2017 to January 2018). Patients included in the practice assessment had to have been managed by the specialist for at least the previous 12 months, be over the age of 18 years, and meet the definition of severe asthma (high-dose ICS/LABA or high-dose ICS plus a second controller plus a reliever as-needed OR a higher level of care defined as high-dose ICS/LABA plus oral corticosteroids, or other add-on agents). Patients receiving biologic therapy were excluded.

The participating physicians were respirologists or allergists/immunologists; 40% of specialists indicated a focus on allergy/immunology clinics, with 70% indicating that they worked in a respirology clinic. There was a small overlap of specialists (10%) who reported practice in both respirology and allergy/immunology clinics. These clinicians were primarily focused on providing patient care (for 73.5% of their clinical time) and practiced in either community clinics (50%) or academic clinics (50%). All the specialists reported seeing at least 5 patients with severe asthma per month, with 30% reporting seeing more than 10 of these patients each month.

Control of severe asthma in Canada

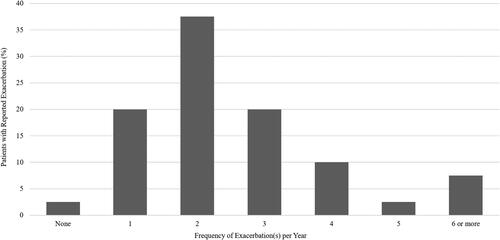

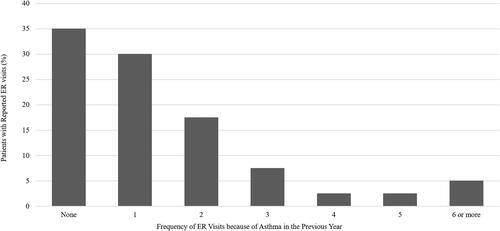

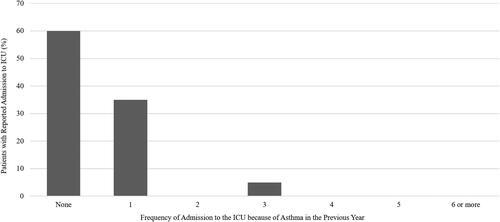

Nearly all patients assessed in the program had experienced at least one exacerbation in the previous year and had a median of 2 exacerbations per year (). Patients often sought emergency medical care because of their asthma, and 65% had visited the emergency department in the previous year, with 5% visiting 6 or more times (). Nonetheless, only 10% of patients seen in the specialist setting were referred by an emergency room physician. Forty percent of patients had been hospitalized in the previous year, with more than 12.5% requiring admission to the intensive care unit ().

Figure 2. Physician-reported emergency room visits in the previous year. Sixty-five percent of patients had visited the emergency room at least once because of asthma in the previous year. ER, emergency room.

Figure 3. Physician-reported hospitalizations because of asthma in the previous year. In total, 12.5% of patients in the practice assessment required admission to the intensive care unit. ICU, intensive care unit.

The relationship between asthma control and use of oral corticosteroids is complicated by the issue of treatment adherence. Non-adherent patients are likely to have greater exacerbation rates and thus greater use of oral corticosteroids. Although medication adherence was regarded as the biggest challenge in patient management (by specialists), nearly two-thirds of patients with uncontrolled severe asthma were estimated to be adherent to their medications. The specialists noted that half of their patients with severe asthma had disease that was difficult to control despite optimal guideline-based treatment.

The practice assessment identified that 48% of all patients and the majority of patients under the age of 60 years (64% of those aged 18–39 years and 53% of those aged 40–59 years) missed work or school days because of their asthma. The oldest group in the practice assessment likely did not report lost days of work because they were retired. While the survey did not assess number of days missed per patient, the percentage of patients with missed days is significant when compared with a survey conducted in British Columbia that identified a 16% absenteeism rate among individuals with asthma.Citation 13 A much greater percentage identified presenteeism (i.e., being present at work but experiencing lost productivity).

Oral corticosteroids use in clinical practice

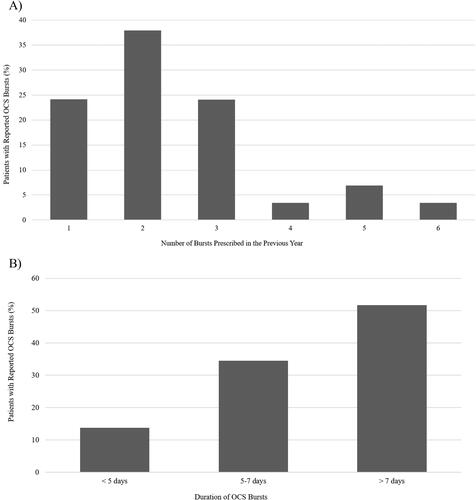

The physicians reported that 95% of severe asthma patients had used oral corticosteroids for their asthma, 72.5% in short “bursts” and 22.5% daily. For patients using oral corticosteroids daily, duration of use ranged from 203 days to 14 years, averaging 4.7 years at a mean daily dose of 11.7 mg. The average number of bursts was 2.4 per year, with the greatest percentage of bursts lasting longer than 7 days or more than 16 days per year of cumulative oral corticosteroid use per year (). Even patients treated intermittently had substantial accumulated exposure. While an exact cumulative dose could not be calculated from the data collected, a conservative estimate of the average cumulative dosage of prednisone was more than 500 mg per patient per year (with assumption of an average daily dose of 30 mg, bursts lasting 7 days, and 2.4 bursts per year). Use of oral corticosteroids was likely underestimated in the practice assessment in that patients provided with on-demand prescription products for management of symptoms of asthma may not be accurately reflected in total use.

Figure 4. Bursts of oral corticosteroids in patients with severe asthma. A) Number of bursts prescribed in the previous year. B) Duration of bursts in patients treated with oral corticosteroids. OCS, oral corticosteroids.

With respect to the adverse effects of oral corticosteroids, the clinicians in the practice assessment were most concerned with increased bone loss followed by bruising, adrenal suppression, and cataracts. A recent real-world cohort study has validated these concerns and reported an increased risk of corticosteroid-associated adverse effects in patients with asthma, with a markedly increased risk of severe infection and smaller increases in the risk of peptic ulcer, affective disorders, and cataracts. The same study also found marginally increased risks of herpes zoster, cardiovascular events, type 2 diabetes, and bone-related conditions in patients using systemic prednisolone compared with patients who were not.Citation 14 Patients who had used oral corticosteroids in the previous year had the greatest risk of all reported adverse effects, with never-users having the lowest risk. Importantly, the risk was more strongly associated with cumulative oral corticosteroid dosage than the greatest dosage used.

Similar findings were reported by Sullivan and colleagues.Citation 15 In their study, there was an increased likelihood of fractures, cataracts, type 2 diabetes, obesity, hypertension, and osteoporosis for patients with asthma who had used oral corticosteroids at any time in the previous year. Patients who received 1–3 prescriptions for oral corticosteroids during the previous year had a 4% greater risk of an adverse effect while those who had received four or more prescriptions had a 29% greater risk. Notably, the increased risk of adverse effects did not return to zero over time; patients who had received oral corticosteroids in the previous year (rather than the current year) retained a 10% greater risk of a poor outcome for each year of exposure. Patients exposed to four or more oral corticosteroid prescriptions for 3 years in the previous decade had almost twice the risk (odds ratio 1.73) of experiencing a new adverse effect compared with patients who did not receive an oral corticosteroid prescription in that time.

In addition to the impact of adverse effects of oral corticosteroid use on the individual, there are significant associated health care costs. A retrospective matched-cohort study using a commercial claims database in the US investigated patients with substantial oral corticosteroid use (more than 30 days of oral corticosteroids annually) and a diagnosis of asthma. The study identified 3,604 patients with asthma and high oral corticosteroid use. The majority (3,011 (84%)) had possible corticosteroid-related adverse effects, with no adverse effects identified in the remaining 593 (16%) patients. Health care utilization and costs were compared between these two groups. Patients with possible adverse effects were more likely to have required office visits and hospitalizations but the number of emergency department visits was similar between groups. Furthermore, patients who experienced adverse effects had a 15% higher mean annual health care cost than those who did not (US$25,168 vs. US$21,882).Citation 16

Biologics for severe asthma

Improved understanding of the pathophysiology of asthma in general, and severe asthma in particular, has enabled development of new therapeutic agents. Canadian clinicians and researchers have played a pivotal role in these developments. There are now several biologic therapies available for the treatment of severe asthma. Omalizumab, an anti-IgE therapy, is indicated for patients more than 6 years of age with moderate to severe persistent asthma, a positive skin test or in vitro reaction to a perennial aero-allergen, and inadequately controlled symptoms.Citation 17 Mepolizumab, reslizumab and benralizumab all disrupt interleukin (IL)-5-mediated activation of eosinophils. Mepolizumab and reslizumab interact with the IL-5 ligand directly, preventing binding with the receptor.Citation 18 , Citation 19 Benralizumab binds to the IL-5Rα receptor, disrupting IL-5 interactions and recruiting immune effector cells to deplete eosinophils (as well basophils).Citation 20 For a more thorough review of postulated mechanisms and biomarkers, the reader is directed elsewhere.Citation 21 , Citation 22

Addition of any one of these new biologic agents may provide significant benefit in appropriately selected patients. The Canadian Thoracic Society recently reviewed the efficacy of these agents in their position statement on the recognition and management of severe asthma.Citation 6 In general, biologic agents have demonstrated the ability to reduce the risk of exacerbation and improve asthma-related quality of life in patients with severe IgE-mediated and/or eosinophilic asthma. The statement acknowledges that use of any biologic agent results in decreased use of oral corticosteroids. In addition, these therapies improve in FEV1 (forced expiratory volume in 1 second).

Risks of exacerbation and severe exacerbation are reduced in patients with moderate to severe asthma treated with omalizumab. (Similar results are seen in the published studies for most biologics showing roughly 50% reduction in baseline exacerbation rate as compared to placebo intervention. Few, if any studies offer a responder analysis quantifying the number of patients achieving the optimal result, complete freedom from exacerbations.) The benefit from omalizumab was maintained in most of the studies conducted in patients with severe asthma.Citation 6 Omalizumab is generally well-tolerated and improved the asthma symptom score and asthma-related quality of life in the majority of the studies.Citation 6 Use of omalizumab is also associated with reduced use of ICS and fewer bursts of oral corticosteroids. The anti‒IL-5 agents (mepolizumab, reslizumab) and the anti‒IL-5Rα benralizumab all provide benefit for appropriately selected patients with asthma. Mepolizumab is efficacious in reducing exacerbations in patients with severe eosinophilic asthma and two or more asthma exacerbations per year. It also allowed for a reduction of the oral corticosteroid dose by 50% in corticosteroid-dependent patients with asthma and persistent peripheral eosinophilia.Citation 6 Reslizumab demonstrated good efficacy in reducing exacerbations in patients with high blood eosinophil counts, at least one exacerbation in the previous year, and treatment with moderate to high dose of ICS.Citation 6 Use of benralizumab resulted in reduced rates of asthma exacerbations, time to first exacerbation, and the rate of exacerbations requiring an emergency department visit in patients with severe asthma and a history of exacerbations despite treatment with moderate- to high-doses of ICS.Citation 6 , Citation 23 All three anti‒IL-5/anti‒IL-5Rα agents have achieved improvements in FEV1 in the range of 100–160 ml as well as improvements in quality of life measures, although reslizumab failed to achieve a defined minimum clinically important difference in quality of life.Citation 6

Anti‒IL-5/anti‒IL-5Rα therapies can be considered for patients 18 years of age and older with severe eosinophilic asthma and recurrent exacerbations despite use of optimal asthma treatment.Citation 6 They may be considered in patients with eosinophilic corticosteroid-dependent asthma to decrease or eliminate the need for oral corticosteroids. Eosinophil counts are a reasonable predictor of response, with greater impact associated with the greatest eosinophil counts. Different cutoff values have been studied for each of the agents.

A recent study suggested that as many as 41% of patients with severe asthma in Ontario meet the criteria for anti‒IL-5/anti‒IL-5Rα therapies, based on a single blood eosinophil count.Citation 10 Given the 8% prevalence of asthma in adults, that 10% have severe disease, and that 25% of these patients are unable to achieve control, an estimated 11,218 (13,680,400 × 0.08 × 0.1 × 0.25 × 0.41) patients in Ontario could be assessed for eligibility for biologics.Citation 10 Albers and colleagues reported that 21% and 20% of patients in a multinational cohort of 502 patients with severe asthma who were not currently treated with biologic therapy were eligible for omalizumab and mepolizumab, respectively.Citation 24 However, there was considerable overlap, in that a majority of these patients were eligible for either anti‒IL-5/anti‒IL-5Rα or anti-IgE therapies. To date, no head-to-head comparisons have been initiated and it is not clear which treatment is the better first-line option in this patient population. The Canadian Thoracic Society has identified the need for comparative research regarding these agents.Citation 6

Lack of awareness is not the only barrier to use of biologic therapies in severe asthma patients. Cost, lack of familiarity or limited experience with new therapies, and under-recognition of severe asthma continue and have impeded optimal use of these therapeutic agents. Coverage by public formularies is variable across Canada () and these disparities may grow as newer biologic and non-biologic therapies become available over the next several years. Only six provinces and territories in Canada list biologic agents for the treatment of severe asthma on their formularies. Despite the advances in our understanding of the pathophysiology of asthma and developments in therapy, the mainstay of treatment for patients with severe asthma is still oral corticosteroids, despite the well-known adverse effects and adverse health outcomes associated with their use.

Table 1. Canadian provincial formulary listing of biologic agents approved for the treatment of severe asthma as of October 2018.a

At the time of this writing, six provincial or territorial formularies have biologic asthma therapies listed but with significant restrictions on their use in most jurisdictions (). Private or personal coverage for these treatment options varies depending on the insurance company involved, compassionate access programs sponsored by the manufacturers, and the ability of patients to pay out-of-pocket for the treatments. Coverage by private insurance plans is difficult to describe. However, there appear to be differences in both initial access to biologics and in the duration of authorized use or lifetime caps on spending on these agents. Some plans may provide complete access, others may provide coverage for only 1–2 years, and some plans provide no coverage. Given the limited reimbursement options for patients, the cost involved, and specialized nature of the drug, use of biologic treatment is presently rare in Canada.

A centralized, appropriately resourced, and coherent access program for biologics for asthma should be considered in Canada. Such a program would limit prescribing of expensive biologics to specific centers with the expertise required to ensure appropriate and effective use of these agents while providing treating physicians with a clear referral pathway for patients who may benefit from these agents. In the UK, assessment of severe asthma and the decision to prescribe these agents are carried out in specialist asthma care centers to help limit the costs of biologic asthma therapies. While such specialist centers may be more difficult to implement in Canada with its widely distributed populations and separate health care systems in each province, a coherent access program for these expensive agents might be considered, particularly in light of both inconsistent public reimbursement and different private payer coverage across the country. Implementation of such a program may allow development of a clear set of parameters for use of these biologics including the optimization of conventional therapies before consideration is given to the use of expensive biologic therapy. Individual payers set specific parameters for use of these products, which introduces uncertainty for patients and ultimately variability in practice, which can lead to disparities in patient outcomes. Such difficulties in securing funding may lead prescribing clinicians to avoid biologic treatments for patients who qualify and would benefit from their use.

Recommendations for change

Specific steps should be considered to address the burden of severe asthma in Canada.

Awareness

At present, use of oral corticosteroids to rescue patients from episodes of worsening asthma is regarded as an unavoidable consequence of the variability of the disease. We must increase awareness that even intermittent use of oral corticosteroids has long-term consequences, with the need for two or more “bursts” of prednisone for asthma within a year being regarded as treatment failure that should prompt reevaluation of management. Shared electronic records should facilitate the tracking of exacerbations and allow such patients to be identified readily.

Research

Despite Canadian participation in the development of treatments for severe asthma, Canada lacks a unified registry of patients with severe asthma.Citation 25 Such a registry could quantify the burden of severe asthma, monitor outcomes, track quality indicators and estimate costs to determine optimal treatments for severe asthma. Prospective collection of well-defined clinical variables would aid in identification of best practices for prescription of biologic treatments. Such data could answer important questions such as the optimal duration of therapy for patients whose asthma has improved whether spontaneously or as the result of therapy.

Access

There is a well-established network of CREs in Canada,Citation 26 but most health care systems do not fund outpatient education for chronic diseases. The CRE offers an effective bridge to, and is an essential component of, the management of severe asthma; it ensures optimal adherence to inhaled therapy and provides patients with tools for effective self-management. CREs are also a valuable resource for family physicians because they are well placed to identify patients with poorly controlled and/or severe asthma.

Family physicians may be unaware of or have disincentives to referral for advanced treatment at specialist centers if available. Increased awareness and incentives to refer to these centers need to be promoted within the context of each provincial system.

Roles of specialists and specialist centers through a “hub and spoke model” need to be considered in Canada. Competent stewardship regarding which patients are offered biologic agents with appropriate evaluation of response to treatment by clinicians with expertise in severe asthma is essential for Canadians to see the value for money spent on these new therapies.

Reasonable criteria for access to these medications must be established by payers to ensure that patients with severe asthma across Canada have equitable access to the best treatment for their disease. Consistent eligibility criteria across public payers may also encourage more consistent private payer coverage in this country.

Conclusions

Severe asthma is associated with a significant burden to patients living with their disease and a disproportionate use of health care resources. Until recently, management relied on oral corticosteroids despite their well-known adverse effects. The availability of biologics, which has demonstrated efficacy and potential to improve the lives of patients living with severe asthma, demands a review of systems to ensure timely referral and access to specialist care, education and, when warranted, targeted biologic therapies.

Declarations of interest

In accordance with Taylor & Francis policy and my ethical obligation as a researcher, I, Erika Penz, am reporting that I have received compensation for consulting and speaking engagements from AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline and Boehringer Ingelheim, companies that may be affected by the research reported in the enclosed paper. I have disclosed those interests fully to Taylor & Francis, and I have in place an approved plan for managing any potential conflicts arising from that involvement.

In accordance with Taylor & Francis policy and my ethical obligation as a researcher, I, Kenneth Chapman, am reporting that I have received compensation for consulting with AstraZeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, CSL Behring, GlaxoSmithKline, Grifols, Kamada, Novartis, Roche and Sanofi Regeneron; have undertaken research funded by Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, CSL Behring, GlaxoSmithKline, Grifols, Kamada, Novartis, Roche and Sanofi; and have participated in continuing medical education activities sponsored in whole or in part by AstraZeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Grifols, Novartis and Teva, companies that may be affected by the research reported in the enclosed paper. I have disclosed those interests fully to Taylor & Francis, and I have in place an approved plan for managing any potential conflicts arising from such involvement.

In accordance with Taylor & Francis policy and my ethical obligation as a researcher, I, JM FitzGerald, am reporting that I have received compensation for consulting and/or speaking engagements with AstraZeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi Regeneron and TEVA; have undertaken research funded by Amgen, AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Johnson and Johnson, Novartis, and Sanofi Regeneron, all paid directly to UBC; have undertaken peer review funded by AllerGen, BC Lung Association and CIHR; and am a steering committee member for the International Severe Asthma Registry and PI for the Canadian Severe Asthma Registry, companies that may be affected by the research reported in the enclosed paper. I have disclosed those interests fully to Taylor & Francis, and I have in place an approved plan for managing any potential conflicts arising from such involvement.

Acknowledgment

Writing and editing support, including preparation of the draft manuscript under the direction and guidance of the authors and incorporating author feedback, was provided by James Patterson, PhD (Bridge Medical Communications, Toronto, ON, Canada).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Haahtela T , Järvinen M , Kava T , et al. Comparison of a beta 2-agonist, terbutaline, with an inhaled corticosteroid, budesonide, in newly detected asthma. N Engl J Med . 1991;325(6):388–392. doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199108083250603.

- Government of Canada . Asthma and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) in Canada, 2018. Report from the Canadian Chronic Disease Surveillance System http://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/diseases-conditions/asthma-chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease-canada-2018.html. Published May 1, 2018. Accessed November 11, 2018.

- Wijesinghe M , Weatherall M , Perrin K , et al. International trends in asthma mortality rates in the 5- to 34-year age group: a call for closer surveillance. Chest . 2009;135(4):1045–1049. doi:https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.08-2082.

- Chapman KR , Boulet LP , Rea RM , et al. Suboptimal asthma control: prevalence, detection and consequences in general practice. Eur Respir J. 2008;31(2):320–325. doi:https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00039707.

- Chapman KR , Verbeek PR , White JG , et al. Effect of a short course of prednisone in the prevention of early relapse after the emergency room treatment of acute asthma. N Engl J Med . 1991;324(12):788–794. doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199103213241202.

- FitzGerald JM , Lemiere C , Lougheed MD , et al. Recognition and management of severe asthma: A Canadian Thoracic Society position statement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;1 :199–221. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/24745332.2017.1395250.

- Bahadori K , Doyle-Waters MM , Marra C , Lynd L , et al. Economic burden of asthma: a systematic review. BMC Pulm Med . 2009;9(1):24. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2466-9-24.

- Israel E , Reddel HK . Severe and difficult-to-treat asthma in adults. N Engl J Med . 2017;377(10):965–976. doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1608969.

- Lougheed MD , Lemière C , Dell SD , et al. Canadian Thoracic Society Asthma Management Continuum ― 2010 Consensus Summary for children six years of age and over, and adults. Can Respir J. 2010;17(1):15–24. doi:https://doi.org/10.1155/2010/827281.

- Husereau D , Goodfield J , Leigh R , et al. Severe, eosinophilic asthma in primary care in Canada: a longitudinal study of the clinical burden and economic impact based on linked electronic medical record data. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol . 2018;14(1):15. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s13223-018-0241-1.

- Foster JM , McDonald VM , Guo M , et al. I have lost in every facet of my life”: the hidden burden of severe asthma. Eur Respir J . 2017;50(3):1700765. doi:https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.00765-2017.

- Asthma Society of Canada. Severe Asthma : The Canadian Patient Journey. https://www.asthma.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/SAstudy.pdf. Published 2017. Accessed September 28, 2018.

- Sadatsafavi M , Rousseau R , Chen W , et al. The preventable burden of productivity loss due to suboptimal asthma control: a population-based study. Chest . 2014;145(4):787–793. doi:https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.13-1619.

- Bloechliger M , Reinau D , Spoendlin J , et al. Adverse events profile of oral corticosteroids among asthma patients in the UK: cohort study with a nested case-control analysis. Respir Res . 2018;19(1):75. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-018-0742-y.

- Sullivan PW , Ghushchyan VH , Globe G , et al. Oral corticosteroid exposure and adverse effects in asthmatic patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141(1):110–116.e7. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2017.04.009.

- Luskin AT , Antonova EN , Broder MS , Chang EY , et al. Health care resource use and costs associated with possible side effects of high oral corticosteroid use in asthma: a claims-based analysis. CEOR. . 2016;Volume 8:641–648. doi:https://doi.org/10.2147/CEOR.S115025.

- Government of Canada . Product monograph: Pr-XOLAIR® (omalizumab). https://health-products.canada.ca/dpd-bdpp/info.do?lang=en&code=74602. Published 2017. Accessed October 1, 2018.

- Government of Canada . Product monograph: Pr-NUCALA (mepolizumab). https://health-products.canada.ca/dpd-bdpp/info.do?lang=en&code=93562. Published 2018. Accessed October 1, 2018.

- Government of Canada . Product monograph: Pr-CINQAIR-TM (reslizumab). https://health-products.canada.ca/dpd-bdpp/info.do?lang=en&code=94330. Published 2017. Accessed October 1, 2018.

- Government of Canada . Product monograph: Pr-FASENRA® (benralizumab). https://health-products.canada.ca/dpd-bdpp/info.do?lang=en&code=96262. Published 2018. Accessed October 1, 2018.

- Pepper AN , Renz H , Casale TB , et al. Biologic therapy and novel molecular targets of severe asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017; 5(4) :909–916. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2017.04.038.

- Kim H , et al. Asthma biomarkers in the age of biologics. J Canadian Soc Allergy Clin Immunol . 2017;13:48.

- Bourdin A , Husereau D , Molinari N , et al. Matching-adjusted indirect comparison of benralizumab versus interleukin-5 inhibitors: systematic review. Eur Respir J . 2018; 52(5):1801393. doi:https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01393-2018.

- Albers FC , Müllerová H , Gunsoy NB , et al. Biologic treatment eligibility for real-world patients with severe asthma: the IDEAL study. J Asthma. 2018;55(2):152–160. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02770903.2017.1322611.

- Bulathsinhala L , Eleangovan N , Heaney LG , et al. Development of the International Severe Asthma Registry (ISAR): a modified Delphi study. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract . [Published online ahead of print, September 1, 2018; doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2018.08.016.

- Canadian Network for Respiratory Care . [Réseau canadien pour les soins respiratory]. http://cnrchome.net/. Accessed November 11, 2018.