ABSTRACT

If nonviolent methods of resistance are effective – and perhaps even more successful than violent methods – why do opposition movements ever resort to violence? The literature on social movement and nonviolent resistance implies that expansion in an opposition movement’s size decreases the risk of violent dissent since successful recruitments improve the movement’s relative power and reduce the necessity of using violence to pressure the state. Nevertheless, a sudden and large expansion in movement size can overburden its organizational capacities and thus increase the risk of violent dissent. Therefore, this study contends while a gradual expansion in the size of the movement decreases the likelihood of violent dissent, a sudden and large expansion in its size raises the risk of violence. These theoretical arguments are evaluated empirically using Nonviolent and Violent Campaigns and Outcomes 2.1 and Mass Demonstrations and Mass Violent Events in the Former USSR datasets. The analysis of these datasets across several regression models supports the developed theoretical arguments.

Introduction

Why do some movements adopt nonviolent methods of resistance while others use violence to achieve their objectives? Despite increased attention to nonviolent resistanceFootnote1 by conflict and social movement scholarship,Footnote2 the determinants and dynamics of adopting violent versus nonviolent strategies have not yet been studied adequately. The few studies in the literature that examine the tactical choice of a dissident movement between violent and nonviolent strategies mostly explore the influence of structural conditions, such as regime type, population, and political instability (Cunningham Citation2013; Chenoweth and Ulfelder Citation2017; Cunningham, Dahl, and Fruge Citation2017). Although structural theories explain the conditions under which a society is prone to violence, they fail to discuss through which mechanisms a dissident movement adopts violent tactics when nonviolent resistance is a viable option.

This study offers a novel argument regarding how the dynamics of movement mobilization affect the use of violent resistance vis–a–vis nonviolent resistance as an outcome of state-dissident interactions. DeNardo (Citation1985) and Lichbach (Citation1987) provide two foundational and classic theories of an opposition movement’s strategic choice between violent and nonviolent resistance. The authors employ a static model to explain how a movement evaluates the costs and benefits of violent tactics vis-a-vis nonviolent strategies. Therefore, these seminal articles on movements’ tactical choice explain resorting to violence as the outcome of a rational unitary actor’s decision. This study contends that violent dissent is not always the outcome of movements’ tactical decisions. The recent literature on political violence and nonviolent resistance maintains that dissident movements do not involve unitary actors (Weinstein Citation2006; Pearlman Citation2011). Indeed, nonviolent movements include radical, emotional, and spoiler members who are prone to provoke violence on their own (Haines Citation1984; Chenoweth and Schock Citation2015). Thus, the development of monitoring and sanctioning mechanisms is required to prevent these members from deviating from nonviolent strategies. However, when a movement experiences a substantial expansion in its participation size in a short period, it might not have sufficient time to develop its monitoring and sanctioning capabilities proportionately to screen and train new members and control existing members who are likely to resort to violence. Thus, I show that while a gradual expansion in the size of the movement decreases the likelihood of violent dissent, a sudden and large expansion in the size of the movement raises the risk of violence. This theoretical argument offers a nonlinear relationship between movement size and the likelihood of violent dissent, allowing us to reconcile the seemingly contradictory predictions of rational choice and crowd behaviour theories about this association.

I evaluate my theoretical arguments about the effects of the dynamics of movement mobilization on violent dissent using the Nonviolent and Violent Campaigns and Outcomes 2.1 datasetFootnote3 (NAVCO 2.1) and Mass Demonstrations and Mass Violent Events in the Former USSR, 1987–992 (MDMV) dataset.Footnote4 The empirical analysis across several statical models supports my theoretical arguments and their robustness.

Why violence?

Over the last decade, scholarsFootnote5 have tried to bridge the gap between the literature within the fields of security studies, conflict resolution, civil resistance, and social movements. As one of their main contributions, these studies correctly argue that society’s lack of political violence does not imply a lack of conflict. In fact, unlike what was virtually a common practice in the intra-state political conflict literature, grieved groups do not decide between remaining silent and taking up arms; rather, they employ, or at least consider employing, civil resistance as a third way of opposing the establishment.Footnote6 Therefore, if we are interested in explaining the use of violence by dissident movements, logical completenessFootnote7 necessitates describing why they do not employ other strategies, such as conventional politics and nonviolent methods of resistance (DeNardo Citation1985). Accepting the existence of nonviolent strategies as a method of resistance raises interesting questions and answering them can broaden our understanding of political conflict in general and political violence in particular.

In fact, violent dissent can be a puzzling observation. Why do some movements use violence despite having lower military capacity than the state? Chenoweth and Stephan’s (Citation2012) findings make this puzzle even more complicated, as they find that civil movements are about twice more successful than violent movements in achieving their goals. Thus, why would an opposition movement adopt an ineffective strategy? To explain violent dissent, some studies have focused on state responses to dissidents,Footnote8 while others have emphasized the political and economic structures and capabilities of the state.Footnote9 Besides, the role of foreign political environment and external actors in political violence is investigated by social scientists.Footnote10 Some conflict scholars also underscore the characteristics of dissident movements that make them more liable to employ violence.Footnote11

Despite the unquestionable impact of other factors, we cannot ignore the fact that violent dissent is directly committed, as either rational or irrational behaviour, by the members of movements. For instance, while state repression can increase the likelihood of violent opposition, there are some movements that have remained nonviolent after experiencing even severe repression. This ability to remain nonviolent is rooted in these movements’ particular traits that make such resilience a feasible option. Thus, explaining movements’ behaviour should be the core of any theory aiming to explain why dissidents resort to violence, and other factors should be discussed in relation to the movements’ actions.

Scholarship on nonviolent resistance has mainly studied the effectiveness of nonviolent movements and the diversity of their tacticsFootnote12 but has largely ignored whether and why some opposition movements reject violent resistance and remain committed to civil resistance. The literature of political conflict also mostly examined militarized and violent disputes, and it has virtually overlooked the existence of nonviolent resistance and its relevance to political violence. Nevertheless, political conflict scholars have initiated a new wave of research and data collection effortsFootnote13 in recent years to explain the tactical choice of violent and nonviolent methods of resistance.

These studies, which primarily rely on structural factors, explore which political, economic, demographic, and social factors contribute to adopting violent and nonviolent tactics. However, despite their merits, these structural theories suffer from several weaknesses and shortcomings. First, structural factors, such as political, economic, and social deprivations, at best explain why individuals are dissatisfied with the status quo, but they cannot help us understand how and when dissident movements adopt violent and nonviolent tactics. Second, these factors often do not change in the short term, so it is difficult to associate them with the quantity and quality of violent incidents, which vary easily in the short term (Chenoweth and Ulfelder Citation2017). Finally, these structural models often focus on one actor, either the state or the movement, and overlook the interactions between the two. However, as recent studies of the dissent-repression dynamics show (Pierskalla Citation2010; Ritter Citation2014; Ritter and Conrad Citation2016), the state and movements are interdependent, and overlooking these interactions can weaken the explanatory power of our theories. Thus, without discounting the importance of structural theories, we need to develop strategic meso-level models to study how the interactions between the state and dissident movements, including its different segments, can lead to violent dissent. Such behavioural models can complement structural models and improve our understanding of violent dissent.

DeNardo (Citation1985) and Lichbach (Citation1987) employ static strategic models to explain the adoption of nonviolent and violent methods of resistance as an outcome of the interactions between the state and dissidents.Footnote14 DeNardo argues that dissident movements cope with the deficiency of mass participation by directing their human resources toward violent strategies. Consequently, if state repression discourages mass participation, then the movement is more likely to resort to violence. Similarly, Lichbach explains that movements substitute nonviolent strategies with violent ones in response to state repression, aiming to demobilize opposition movements. Therefore, both deNardo and Lichbach highlight the importance of popular support in movements’ decision between methods of resistance. These classic theories of opposition movements’ tactical choice suggest that the expansion of opposition movements decreases the need for using violence to compensate for the inadequacy of pressure on the state.

However, this expectation contradicts theoretical arguments in sociology and psychology about ‘crowd behavior.’ Le Bon (Citation1898) and Sighele (Citation1890) are among the first sociologists who tried to reject Hobbes’s rational model of civil violence and formulated it as an irrational behaviour through offering crowd theory. Based on this theory, the members of a group are impulsive, irrational, and incapable of judgment because the formation of the group boosts everyone’s perceived power due to synergy (Tarde Citation1968; Le Bon Citation2002). In fact, while individuals had to follow society’s rules, becoming a member of a group lets them be less scared of the coercive power of the state, so they are more likely to resort to violence. Therefore, according to the crowd behaviour theories, an increase in the size of protestors makes it harder to control the violent behaviour of the crowd as a ‘wild and [irrational] beast’ (Tarde Citation1968, 323).

Indeed, anecdotal evidence also shows that large peaceful protests without the state’s brutal force can lead to violent dissent. For instance, during the 2009 Iranian presidential election protests, known as the Green Movement, millions of people marched silently in the streets of Tehran, Iran’s capital, on June 16, 2009, to oppose the election results and the state’s brutal response since the election day. It is still the largest anti-government protest after the 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran, and it remained peaceful by both protestors and the state sides until toward its end. While the protest was peaceful and security forces tolerated it during the day, it turned into violent clashes between protestors and police in several places at its end. The question is why the protest led to several deadly confrontations if the Green Movement leaders could demonstrate their power by organizing a massive silent march and security forces’ primary strategy was standing aside and monitoring the protestors.

The following parts of this study develop a theoretical model to contend that there is a nonlinear association between expansion in the size of an opposition campaign and the likelihood of violent dissent. The offered theoretical framework reconciles the theoretical arguments developed by DeNardo (Citation1985) and Lichbach (Citation1987), on the one hand, and ‘crowd behavior’ scholarship, on the other hand.

Violent and nonviolent resistance

Consider a society in which a group of citizens is discontented with the status quo; however, change via democratic institutions is not an option due to either lack of efficient democratic institutions or doubt about its efficiency. Therefore, the discontented citizens form an opposition movement to compel the state to alter its current policies by causing disruptions in the governance of society.Footnote15 If the pressure on the state reaches a certain level, the desired adjustments in policy will be realized. Every movement has two primary options to disrupt the government and put pressure on the state: violent and nonviolent methods of resistance.

The term ‘violence’ is commonly used in the political violence literature, and actions such as murder and physical injury are unanimously considered violent behaviour. However, there is no consensus on whether using physical forces with lower intensity or targeting non-human entities are considered violent. Following Tilly (Citation1978), I define violence as ‘any use of physical force’ (174). Thus, any resistance tactics involving physical force, no matter how powerful the physical force is, toward whom or what it is applied, or whether it is applied with or without weapons, is considered violent resistance. For example, damaging private or public buildings is an act of violent resistance, according to this definition. On the other hand, using harsh chants in protests is not a violent act based on the definition adopted in this study, even if it is morally problematic.

Consistent with the above definition of violence, nonviolent resistance includes all tactics that do not require physical force (Sharp Citation1973). Thus, acts of disobedience, non-cooperation, disruption, persuasion, and so forth, to the extent that they do not involve physical force, are regarded as nonviolent resistance, regardless of whether they are legal. For example, traffic blockage is a nonviolent tactic, as long as it does not entail damaging private and public properties, although unauthorized blockage of roads is illegal in most countries.

While both violent and nonviolent actions disrupt the country’s governance for the state authorities, the intensity and the cost associated with these actions differ. Nonviolent movements mainly rely on socio-economic actions to encourage people not to cooperate or obey the state so that the government apparatus cannot function properly. On the other hand, movements that use violent means of resistance disturb the state’s functionality by employing physical forces to eliminate state officials or properties. For instance, when workers of a state-owned oil refinery strike, they deprive the state of its financial resources. Alternatively, these workers could choose to destroy the refinery to interrupt the income flow of this business. Both actions contribute to disrupting the governance of the state. However, the latter is more coercive and has a longer effect, although it requires a smaller group.Footnote16

If violent tactics are more disruptive, why do some dissident movements choose nonviolent tactics? One might argue that supplying weapons, ammunition, and explosive materials is costly. This is a valid point, but how difficult is it to actually equip a movement with violent means? Finding stone, knife, and chemical materials is not an impossible task. How complicated is it to make a Molotov Cocktail? Moreover, due to international and regional rivalries, it is not uncommon for foreign countries to assist dissidents to smuggle weapons into the country, similar to what happened in Syria and Yemen.

No doubt, the cost of resorting to violence-such as an increase in state repression and losing legitimacy and supports-affects a movement’s decision about its preferred method of resistance. By shifting to violent strategies from nonviolent ones, the movement evolves into a different political actor, and the political environment in which the movement interacts with the state significantly changes. Furthermore, it is usually difficult to reverse this decision and de-escalate a conflict. Thus, despite potentially favorable consequences of resorting to violence, such as being more disruptive, the movement also considers its negative consequences.

Dynamics of movement expansion and violent dissent

Arendt (Citation1970), in her essay on violence, argues that we need to distinguish power from violence:

[I]t is insufficient to say that power and violence are not the same. Power and violence are opposites; where the one rules absolutely, the other is absent. Violence appears where power is in jeopardy[…] (56).

The recent quantitative studies on nonviolent resistanceFootnote17 similarly discuss the link between opposition movements’ size and their adopted resistance method. These studies argue that movements relying on civil resistance are even more dependent on the masses to put sufficient pressure on the state to achieve their objectives. A handful of people is sufficient to launch a terrorist attack. However, a sufficiently large number of people is necessary to stage an effective strike.Footnote18 Furthermore, popular mobilization plays a decisive and essential role in the success of nonviolent movements (Chenoweth and Stephan Citation2012; Nepstad Citation2011). Accordingly, if a nonviolent movement fails to recruit enough people for effective civil resistance, its members may doubt the effectiveness of this method, which makes violent resistance a viable alternative.

However, the classic theoretical expectation that the expansion of movement decreases its tendency to use violence has two flaws. These flaws prevent us from explaining why large peaceful protests turn to violence. The first one is assuming that different groups attending in oppositional movements share the same preferences. Cunningham, Dahl, and Fruge (Citation2017) explain that the members of opposition movements debate and evaluate the available resistance strategies, and these discussions affect the coordinated resistance tactics. However, the question is what guarantees the commitment of all members of an opposition movement to the tactic that is the outcome of discussions about the costs and benefits of different options. The second flaw is overlooking the dynamics of mobilization and how the expansion paths that a movement experiences affect its tendency to resort to violence. Below, I relax the unitary actor assumption and explain how incorporating it with different dynamics of mobilization lead to a better understanding of violent dissent.

While the classic literature assumes that an opposition movement is a unitary actor, recent studies challenge this assumption. Pearlman’s (Citation2011) theory of organizational mediation relaxes the movement homogeneity assumption to explain the effect of movement cohesion on the efficacy of nonviolent campaigns. She argues that the prevailing path to nonviolent resistance is only available when the movement is cohesive. Chenoweth and Schock (Citation2015) also show that nonviolent movements usually have a radical flank, whose role in the movement and relationships with the other groups within the movement can change over time.

Indeed, the homogeneity assumption of social movements is far from what occurs in the real world. Some social movement members are risk-takers, and they are more radical than other members, so their preferred method of resistance is violence (Haines Citation1984). Some members cannot control their emotions, so they are likely to react to state repression violently (Rule Citation1989). Lastly, every social movement is prone to recruit spoilers who are either security agents infiltrating the movement to radicalize it or criminals joining for looting opportunities (Davenport Citation2014).

While individuals constitute collective groups that augment their power and resources to obtain jointly produced benefits, their egoism can imperil the collective decision and outcomes. Thus, these groups need to develop monitoring and sanctioning mechanisms to minimize the risk of deviations from the established norms and rules (Hechter Citation1995). Weinstein (Citation2006) explores the necessity of monitoring and sanctioning mechanisms in rebel groups: groups relying on economic endowments are more prone to recruit ‘opportunistic’ members who are more likely to use violence to appropriate civilians’ belongings. In contrast, ideological groups mostly include ‘activist’ members who believe in the causes of movement and pursue long-term ideological and political objectives, so they are less likely to use violence because of materialistic incentives.

As discussed before, the expansion of movement is an encouraging sign that the opposition can recruit undecided sympathizers, mobilize them for its cause, and wield power to pressure the state. Therefore, the expansion of a movement is associated with more tactical commitment to nonviolent resistance and a lower probability of resorting to violence. However, not all types of expansions guarantee nonviolence. A movement can increase its size gradually over several periods. Alternatively, it can reach a large size because of a sudden and significant change in only one period. Kuran (Citation1989, Citation1991) theorized the mechanism behind the rapid and large changes in the size of revolutionary movements. He argues that citizens can falsify their preferences about the status quo and keep their genuine preferences private. However, if they see enough citizens reveal their preferences publicly, for instance, by organizing protests, we should expect a cascade effect where the size of anti-government movements expands quickly within a short period.

Although a sharp expansion increases the movement’s power, and the strategic necessity of resorting to violence decreases, this expansion can challenge the screening, monitoring, and sanctioning capability of movements in at least two ways. First, the current radical, emotional, and spoiler members are more likely to find an opportunity to deviate from nonviolent resistance tactics as the rapid expansion challenges the monitoring and sanctioning capacity of movements. Movements with strong organizational capacity usually establish mechanisms to monitor members and punish those who deviate from the movements’ core strategies. For instance, during the Arab Spring in Egypt, the opposition organized checkpoints to prevent taking weapons and violent tools to the focal point of protests, Tahrir Square.Footnote19 If, within a short period, a large number of discontented citizens decide to join the opposition and attend protests, the current capacity of the movement might not be robust enough to provide the same level of monitoring of compliance with nonviolent principles. This decline in organizational capacity can give an opportunity to radical and spoiler members to behave violently. These deviants can also find new sympathizers due to the fast and large expansion in movement size.

Second, there is evidence that successful nonviolent movements familiarize their members with nonviolent resistance principles and train them to remain resilient. For instance, evidence from the Civil Rights Movement in the US shows that the members of this movement received training to remain nonviolent before they participated in a protest (Cosgrove Citation2013). In addition, recent experimental studies confirm that providing information on the principle and success rate of nonviolent resistance improves individuals’ attitudes toward it (RezaeeDaryakenari and Asadzade Citation2020). A rapid and substantial increase in movement size can interrupt the training plans that movement leaders establish to enhance the coherence of their movement and their members’ commitment to nonviolent resistance.

Therefore, a significant and rapid expansion in movement size can make all movements prone to violent dissent. Opposition movements without an effective screening, monitoring, and training capacity are at a higher risk of resorting to violence in response to a rapid and large expansion. However, movements with strong organizational capacity are not fully protected against the adverse effects of these swift and significant changes. This is because not all of these movements have the capability to quickly adjust their screening, monitoring, and training capacities in proportion to their expansion. Therefore, we can expect that all movements become more prone to use violence in response to a large and rapid expansion, but the extent of this vulnerability is associated with their organizational capacities and adjustment capabilities.

The above theoretical discussions suggest that the association between an increase in movement size and violent dissent is not linear. A gradual expansion allows the movement to better screen recruits and to improve its monitoring and training capacity accordingly. This balanced growth empowers the movement and lowers the need to resort to violence due to tactical reasons. Besides, it minimizes the risk of unintentional violence as the pressure on monitoring and training capabilities is manageable. Therefore, a sufficiently small and steady expansion of movements decreases the likelihood of violent dissent.

On the other hand, since a rapid and large expansion in size is associated with weakening the monitoring and training capacity of opposition movements, we can expect that these types of expansions can increase the risk of violent dissent. This nonlinear association allows us not only to offer an explanation for why some large peaceful protests turn to violence but also to reconcile two seemingly contradictory theories: power in numbers literature that predicts an increase in movement size decreases the risk of violent dissent, and crowd behaviour theories that argue an increase in size makes movements more prone to resort to violence.

Considering the above arguments, I posit the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis: While a gradual increase in the size of a movement decreases the likelihood of resorting to violence, a large and rapid expansion of a movement raises the risk of violent resistance.

Empirical analysis

I estimate a series of statistical models to test my hypothesis on the association between mobilization dynamics and violent dissent. I use two datasets: the Nonviolent and Violent Campaigns and Outcomes 2.1 datasetFootnote20 (NAVCO 2.1) and the Mass Demonstrations and Mass Violent Events in the Former USSR, 1987–1992 (MDMV) dataset.Footnote21

NAVCO 2.1 covers 384 nonviolent and violent mass movements across the world from 1945 to 2013. In addition to adding some new attributes to the dataset, NAVCO 2.1 expands the campaign cases relative to its previous version, NAVCO 2.0. The total number of campaigns increased from 250 in NAVCO 2.0 to 384 in NAVCO 2.1, and the total number of observations increased from 1,726 campaign-year in NAVCO 2.0 to 2,717 campaign-year in NAVCO 2.1. The codebook of NAVCO defines ‘[…] a campaign as a series of observable, continuous, purposive mass tactics or events in pursuit of a political objective.’ (Chenoweth and Shay Citation2019, 2) According to the structure of this data set and consistent with my developed hypothesis, I define campaign-year as the unit of analysis.

Since NAVCO 2.1 is not limited to a geographic location or campaign, I use it to test the generalizability of my theoretical arguments. Also, the NAVCO dataset has been widely employed in the literature, and using it for the empirical evaluation of theoretical arguments in this study allows us to compare the results with other studies on violent and nonviolent movements.

Nevertheless, some might rightfully argue that using a campaign-year dataset might be temporally too aggregate to capture the dynamics discussed in the theoretical section. I, therefore, use MDMV dataset as temporally more fine-grained data on mass violent and nonviolent events. Unlike NAVCO 2, MDMV is an event database that includes information on 6,663 protest demonstrations and 2,177 mass violent events across the entire territory of the former Soviet Union from January 1987 through December 1992. After the liberalization of Soviet politics under glasnost, the republics of the Soviet Union experienced a series of nationalist movements against Moscow’s policies and local governments in the republics (Beissinger Citation2009). Beissinger (Citation1998) uses a multiple-source media sample of Western and local Soviet sources to code these events and collect them as a dataset.

While NAVCO 2.1 is an annual dataset and sets a relatively high threshold of violence, discussed below, to code a campaign as violent, MDMV reports violent and nonviolent actions by state actors and protestors at the daily level. This allows us to use a more disaggregated temporal unit of analysis for MDMV data to test the developed hypothesis empirically. I choose the week-movement as the unit of analysis for statistical analysis of the MDMV dataset. Davenport (Citation2007) and Schrodt (Citation2012) discuss the challenges of choosing the temporal aggregation level for daily reported conflict events. News sources can record and report daily conflict events with several days delay, and using day as the temporal level of analysis can lead to measurement error. Therefore, I choose week-movement as the unit of analysis to balance the benefits of a disaggregated analysis and the drawbacks of using the day as the temporal unit of analysis.

Dependent variable: In the real world, it is difficult to find opposition movements that purely rely on either violent or nonviolent tactics while entirely ignore the other one. Thus, coding whether a movement is violent or nonviolent is challenging, particularly if the dataset is aggregated temporally to a yearly level. NAVCO 2 solves this coding problem by ‘characterizing campaigns are “primarily nonviolent” or “primarily violent” based on the primacy of resistance methods employed’ (3). I code the categorical dependent variable violent as ‘1’ if the primary method of resistance in a campaign year is violence and ‘0’ otherwise.

Unlike NAVCO 2.1, the MDMV dataset reports all violent attacks on people or property caused by 15 or more persons. Therefore, the dependent variable, violent, in this dataset is a binary variable that is coded ‘1’ if dissidents’ actions led to human casualties and property damage over the week, and ‘0’ otherwise.

Independent variable: NAVCO 2.1 reports the total number of campaign participants during the year, which is the highest recorded/estimated participation at the peak of the campaign-year. MDMV reports the estimation of the total number of participants in mass demonstrations and mass violent events per day, and I take the weekly mean of these reported participants in these events.

The developed hypothesis in the theoretical section explores the nonlinear association between expansion in the size of movements and the likelihood of violent dissent. Therefore, I define expansion in size as the independent variable in my statistical analysis. If the change in participation size is positive, expansion in size is equal to this positive change. However, if the change in participation size is negative, the expansion in size is coded as ‘0’. Also, I include the square of expansion in size to the estimated models since the hypothesis suggests a nonlinear association. To find support for the hypothesis, the estimated coefficient for expansion in size and its square should be negative and positive, respectively.

I also include a set of control variables to further insulate the estimated coefficients from confounding effects. Contentious cycle and resource mobilization models of dissident movements argue that any decreases in the movement size increase the risk of violent dissent (Tilly Citation1977; Crenshaw Citation1981; DeNardo Citation1985; Della Porta and Tarrow Citation1986; Tarrow Citation1993; Kalyvas Citation2006; Wood Citation2014). Among these studies, those that examine the rebel groups are not designed to study the transition from nonviolent strategies to violent tactics. In fact, they evaluate the association between resource loss and the escalation of rebel violence. Studies on the use of violence by nonviolent movements are also bivariate correlation analyses of a small number of cases. To evaluate these claims and control their effects, I include the size of campaigns and their negative changes relative to the previous period as control variables.

The literature on political violence also examines the effect of state repression on the likelihood of dissident. The findings regarding this association are highly inconsistent (See Davenport (Citation2007) for a detailed discussion). While some scholars find a positive association (Francisco Citation2004; Ritter Citation2014), some studies support a negative association (Hibbs Citation1995). Some other studies also find both effects (Muller Citation1985; Rasler Citation1996; Moore Citation1998; Cunningham and Beaulieu Citation2010). NAVCO 2.1 reports the degree of state repression in response to campaign activity. MDMV also reports the degree of coercion used by authorities at each event. If the authorities arrest or injure dissidents, I code it as state repression. This variable is included in the estimated models using NAVCO and MDMV datasets, and it is labelled as repression.

As discussed below, I use different estimation methods to minimize the risk of biased estimation caused due to omitted variable problems. However, the NAVCO dataset allows exploring the effects of some other commonly used factors in the literature of political violence and nonviolent conflict. I add some of these variables in the models estimated using NAVCO data to explore their effects in my analysis. The role of democratic institutions in pacifying political grievances has frequently been discussed in political conflict literature (Krain and Myers Citation1997; Hegre Citation2001; Vreeland Citation2008; Hendrix and Haggard Citation2015), and it is known as ‘domestic democratic peace’ (Davenport Citation2007). Therefore, I include in my model a categorical measure of democracy using polity2 from the Polity IV project (Marshall and Jaggers Citation2002). Following the suggestion in Polity IV, regimes with a polity2 score of 6 and higher are coded as democratic, and the democracy variable is coded as ‘1’ for these regimes and ‘0’ for others.

Also, Pearlman (Citation2011) underlines the role of organizational cohesion in the adopted resistance tactics. I control for the structure of campaign organization and leadership among opposition groups within dissident movements by including the campaign leadership structure variable from NAVCO 2.1. This variable is coded ‘1’ if the campaign has a centralized command and control and ‘0’ otherwise. This variable is labelled as hierarchical structure. I also will use this variable to explore whether a central and strong leadership can help a movement to handle the challenges of a rapid expansion in its size. As argued in the theoretical section, I expect that movements with a centralized and hierarchical command and control structure should be able to cope with the adverse effects of a rapid expansion, and this decreases the likelihood of violent dissent.

Lastly, although all the campaigns recorded in NAVCO 2 project at one time or another held ‘maximalist’ goals, there is heterogeneity across their goals. Some movements want to overthrow an existing regime, and some others want to achieve self-determination. The differences in the success rate of nonviolent campaigns with different goals (Chenoweth and Stephan Citation2012) and the heterogeneity in the members of movements can affect their attitude toward violent and nonviolent resistance. I control this factor by including campaigns’ stated goals in the models estimated using NAVCO data.

Furthermore, I lag all of the independent and control variables. This helps to some extent decreases the risk of heterogeneity owing to the possibility of a simultaneous effect between resistance method and mobilization dynamics. The statistical summary of dependent, independent, and control variables is reported in the Online Appendix.

I estimate my regression models using different methods. Although the dependent variable is a binary variable, I first estimate linear probability models (LPM) to address possible concerns that some scholars raised about nonlinear probability models (NLPM) (Angrist and Pischke Citation2009). Then, I estimate the same regression models using logit methods.

The omitted variable problem is a source of endogeneity and biased estimations in regression analysis. For instance, Wasow (Citation2020) discusses how campaign tactics can influence media coverage and their framing of protesters’ demands. These mechanisms indeed can affect how movements decide about their method of resistance. On the one hand, collecting this type of data for cross-national analysis can be challenging. On the other hand, ignoring them in regression analysis can lead to biased estimations due to the omitted variable problem. I minimize the risk of the omitted variable problem by estimating fixed effects models. Including both movement and time fixed effects helps to a good extent capture time-variant and time-invariant unobserved factors that can lead to biased estimations. The time fixed effects are year and week in NAVCO and MDMV datasets, respectively.

Furthermore, to control for the possible problem of heteroskedasticity and serial correlation, I estimate robust and clustered standard errors. Across different estimated models, I cluster the standard errors by both country and campaign. To ensure that the hierarchical structure in data does not lead to a biased estimation, I also estimate several multilevel models at different levels. Specifically, two-level models allow fitting a fixed-effect modelFootnote22 at the first step.

Lastly, some might argue that past violent and nonviolent events can affect the likelihood of resorting to violence in the current period. Consequently, I add the number of periods without violent dissent and its square and cube, labelled as nonviolent cubic spline, to the estimated model to control for temporal dependence, as suggested by Beck, Katz, and Tucker Citation1998.

Estimation results and analysis

and report the results of estimated models using the NAVCO and MDMV datasets, respectively. Consistent with the developed hypothesis suggesting a nonlinear association between expansion in size and the likelihood of violent dissent, the estimated coefficients of the expansion in size are negative while the coefficients of its square are positive. All these coefficients across different statical models are statistically significant (p < .05). I first followed Angrist and Pischke (Citation2009) and estimated a linear probability model (LPM) with campaign and year fixed effects. The estimated standard errors are robust and clustered at the country level. Then, I estimated a series of nonlinear logit model. Since some might be concerned that cross-section fixed-effects can absorb all the variations, I first estimated two models (columns 2 and 3) without campaign fixed-effects but with robust standard errors clustered at the country and campaign level, respectively. Then, I estimated a 2-level logit model with both campaign and year fixed effects (column 4) to capture unobserved factors at the campaign level using hierarchical modelling. The last column in and presents estimation results for a 3-level logit model to explore whether factors associated with country and campaign can affect the estimated results. These results across different models are robust and consistent with proposed theoretical arguments that expansion in movement size is a sign of their power, and this decreases the likelihood of resorting to violence. However, if this expansion is sufficiently large, then the movement’s monitoring and punishment mechanisms can fail to control the radical, emotional, and spoiler members. Thus, the environment would be ready for these members to deviate from the movement’s strategy and provoke violence.

Table 1. The estimated effects of expansion in size on violence using NAVCO data.

Table 2. The estimated effects of expansion in size on violence using MDMV data.

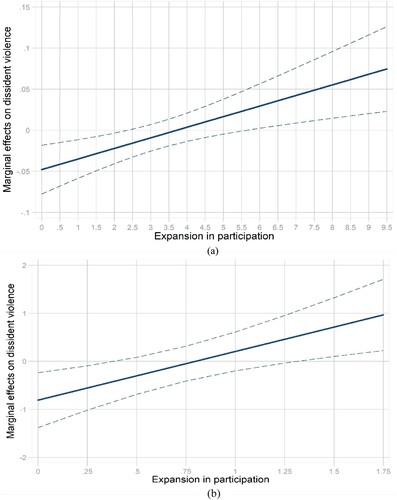

Moreover, I plotted the marginal effects of expansion in participation on violent dissent across its different values. shows that expansion in participation initially has a negative effect on violent dissent, but it loses its pacifying effect as the size of expansion increases until its effect becomes statically not different from zero. After passing the threshold of around 3.5 million expansion in a year for the NAVCO dataset and .8 million expansion in a week for the MDMV dataset, the estimated effect of expansion on the likelihood of violence turns to positive values.

Figure 1. The marginal effects of expansion in size on violent dissent with 90% confidence intervals using NAVCO dataset (a) and MDMV dataset (b)

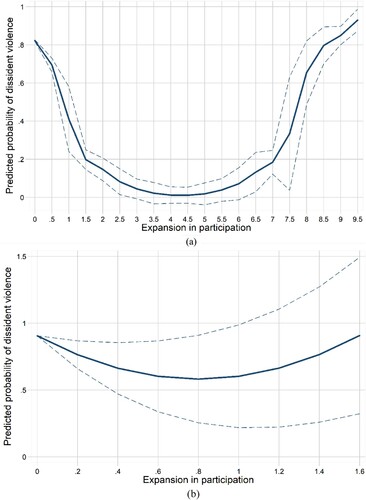

I also plotted the marginal effects of expansion in participation on the predicted probability of violent dissent () to better visualize the theorized nonlinear association using the estimated models. Comparing the predicted probability for NAVCO (:a) and MDMV (:b) reveals that the substantive effect is stronger for NAVCO analysis. This can be due to the difference in the temporal unit of analysis. NAVCO yearly analysis makes it possible that a campaign experiences a large expansion in its size, and this increase in the number of cases reduces uncertainty about the estimated results and thus shrinks the confidence interval. On the other hand, since it is possible but not common that movements experience a large expansion in their size over a week, this smaller number of observations decreases the confidence in estimated results and increases the confidence interval. Despite a relatively weaker substantive effect in the MDMV analysis, the estimated probabilities still show that the likelihood of violent dissent first declines, but it increases after a sufficiently large expansion.

Figure 2. The predicted probabilities of violent dissent at different levels of expansion in size with 90% confidence intervals using NAVCO dataset (a) and MDMV dataset (b).

Regarding the control variables, the estimated coefficients of a decrease in the size of movements are noteworthy. The estimated models using the NAVCO dataset, consistent with literature,Footnote23 show that a decrease in campaign size increases the likelihood of violent dissent. However, the results of MDMV analysis reveal a negative association between these two variables.

Moreover, I find that repression decreases the likelihood of violent dissent in models using the NAVCO dataset, but they are not statistically significant (p > .1). However, the estimations of this association using the MDMV dataset are positive and statistically significant across all models. These findings support the studies that argue repression can intensify violence among protestors (DeNardo Citation1985; Sullivan and Davenport Citation2017; Davenport Citation2014). Similarly, the empirical results show a positive association between democracy and violent dissent (Asal and Rethemeyer Citation2008), but it is not statistically significant. Furthermore, campaigns with significant institutional reform, policy change, greater autonomy, and anti-occupation objectives are less prone to using violence than campaigns with regime change agendas, and secessionist movements are not different from this latter group. Finally, the estimation results show that the probability of violence is higher for campaigns with a centralized and hierarchical structure. While such a campaign can have a higher monitoring and controlling capacity, this top-to-bottom structure can lead to less satisfaction with the decisions made at the leadership level, and radical segments of the campaign deviate at some points from its primarily nonviolent strategy.

On the other hand, this capacity should help oppositional campaigns to mitigate the adverse effects of a rapid expansion in size and recruiting new members, as discussed in the theoretical section. I explored this effect as one of the robustness checks and reported its results in the online appendix (Table A2). The estimated conditional effects of hierarchical structure on the association between expansion in participation and violent dissent are negative and statistically significant. This supports the discussed arguments in the theoretical section that movements with a strong organizational capacity can better manage the adverse effects of a rapid and large expansion in their size, so they are less likely to resort to violence.

In their book, Chenoweth and Stephan (Citation2012) ascertain that nonviolent campaigns are almost twice as successful as violent campaigns in achieving their objectives. Some might doubt these results because of the possibility of an endogeneity problem. In fact, there may be a bidirectional association between the campaign’s adopted strategy and its success. Chenoweth and Stephan address this concern by estimating a two-stage model in which the campaign in the first stage concerns the method of resistance, and the influence of the resistance method on the likelihood of success is then estimated. This two-stage model estimation also adds to the evidence for nonviolent campaigns’ higher success vis-a-vis violent campaigns. However, the authors do not use any theoretical framework to justify their estimated model of campaigns’ decision in the first stage.

Since this study models the adopted methods of resistance by oppositional movements, I re-estimate the effect of resistance methods on movement success in the NAVCO dataset. To do so, I estimate a simultaneous equation model (SEM) (Amemiya Citation1977), with two equations in which the primary method of resistance is an endogenous variable. The first equation is exactly the main empirical model of this study, and the second equation estimates the influence of the resistance method, as an endogenous variable, on the likelihood of campaign success. I control for campaign size, repression, democracy, campaign goal, and hierarchical structure accordingly. The estimations of these equations are reported in the online appendix (Table A3). These results are consistent with Chenoweth and Stephan’s (Citation2012) findings that resorting to violence decreases campaign success. These results also suggest that larger campaigns are more successful than smaller campaigns in achieving their objectives.

Conclusion

The recent scholarly attention has been largely devoted to the relative effectiveness of nonviolent resistance, and there have not been enough studies on how violent and nonviolent tactics as methods of resistance emerge from state-dissident interactions. Few studies discuss the structural determinants of these resistance tactics to determine which campaigns adopt nonviolent methods of resistance. However, they do not adequately explore the dynamics of mobilization to illuminate when and why dissidents resort to violence.

This study improves our understanding of how dynamics of mobilization affect the probability of violent dissent. It offers theoretical discussion and empirical support to reconcile two seemingly contradictory theoretical expectations from rational choice and crowd behaviour literature. The article demonstrates that a moderate expansion in the size of a movement decreases violence risk because of increases in popular support. However, a large expansion of the movement overburdens its monitoring, sanctioning, and training capacities, raising the risk of violent dissent. The results across different statistical models and using NAVCO and MDMV datasets support the proposed nonlinear association.

The findings of this study provide further evidence for the scholarship that emphasizes the importance of relaxing the unitary actor assumption in conflict literature (Weinstein Citation2006; Pearlman Citation2011). Most studies on disaggregating non-state actors in conflict literature focus on rebel organization, and there have been several data collection projects to advance it (For example, see Braithwaite and Cunningham Citation2020). However, the literature on low-intensity conflict and nonviolent resistance still lacks proper large-N data for the cross-national study of organizational features of movements. For instance, as this article underlines, we need to better understand mechanisms that movements develop to maintain cohesion and ensure their members’ commitments to strategies. Future data collection projects dedicated to gathering data on the organizational foundations and changes of social movements and political dissent can contribute significantly to this literature. This would allow scholars to tease out underlying mechanisms linking organizational aspects of movements to their tendency to resort to violence.

In the empirical section, I employed several statistical techniques to minimize estimation bias. One of the main concerns is estimating a biased model due to an endogeneity problem. Using both movement and time fixed-effects significantly decreases the risk of endogeneity caused by the omitted variable problem. Reverse causality also is a known source of endogeneity and biased estimation. Besides, it makes interpreting the direction of estimated association difficult. However, since the independent variables are expansion in size and its square, it is hard to argue that violent dissent is causing the nonlinear association between the independent and dependent variables (See ). Therefore, we can infer that the expansion in size and its square are responsible for changes in the probability of violent dissent, not the other way round.

However, the possibility of endogeneity caused by a selection problem cannot be addressed and explored adequately considering the available data. Not all potential movements and protests make it into the conflict datasets such as NAVCO and MDMV. Indeed, the collective action problem prevents observing some potential movements. For instance, Ritter and Conrad (Citation2016) show that expecting severe state repression prevents dissatisfied civilians from organizing a protest. If these failed movements could overcome their collective action problem, they may behave differently from what is discussed in this article. This non-randomly selection of sample can lead to biased estimations if this selection is correlated with the dependent variable, violent dissent in this study.Footnote24 This is a fundamental problem with conflict research using observational data to study movement tactics and their outcomes, and there is no easy solution to address this problem.

However, there are some solutions that future research can consider exploring. Moving beyond news sources and using new sources of data like social media in collecting data on conflict processes can help mitigate this problem. Currently, conflict datasets heavily rely on news sources to gather their data, and this means events that are not newsworthy do not make it to the news and thus conflict datasets (Davenport Citation2007). In recent years, some scholars have used social media data to analyse conflict processes by examining changes in attitudes and preferences at the individual level (King, Pan, and Roberts Citation2017; Stukal et al. Citation2019). Analysing the social media accounts of grieved citizens can help us learn when they fail to overcome their collective action problem. Combining information on these failed opposition movements from social media with data on successfully mobilized movements from news sources would significantly help to tackle the discussed selection problem using Heckman’s solutions (Citation1976; Citation1979).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 I use the terms nonviolent resistance and civil resistance interchangeably.

2 For example, see Chenoweth and Stephan Citation2012; Cunningham Citation2013; Asal et al. Citation2013; Braithwaite, Braithwaite, and Kucik Citation2015; Chenoweth and Ulfelder Citation2017; Cunningham, Dahl, and Fruge Citation2017.

3 Chenoweth and Shay Citation2019.

4 Beissinger Citation1998.

5 For example, see Chenoweth and Stephan Citation2012; Pearlman Citation2011; and Nepstad Citation2011.

6 Even sovereign states, equipped with military capabilities, evaluate the possibility of achieving their objectives through non-military options, such as third-party mediation and economic sanctions, before taking military action.

7 DeNardo (Citation1985) uses ‘logical completeness’ to address this logical and theoretical issue, but a more specific term for this type of theoretical inconsistency is negation completeness or syntactically completeness, which is discussed and coined by Kurt Gö del. See Heijenoort (Citation2002) for a detailed discussion of incompleteness theorems.

8 For example, see Lichbach Citation1987; Moore Citation1998; and Cunningham and Beaulieu Citation2010.

9 For example, see Crenshaw Citation1981 Mason and Krane Citation1989; Henderson Citation1991; Poe and Tate Citation1994; Davenport Citation1996; Eubank and Weinberg Citation2001; Tilly Citation2003; Tilly and Tarrow Citation2006; Asal and Rethemeyer Citation2008; and Shadmehr and Haschke Citation2016.

10 Skocpol Citation1979; Roberts and Ash Citation2009; Fair Citation2005; Gallo-Cruz Citation2012, jan. 1; and Karakaya Citation2018.

11 Gurr Citation1971; Tilly Citation1978; Della Porta and Tarrow Citation1986; Tarrow Citation1993; Tarrow Citation1989; Tarrow Citation1994; Mason Citation1996; Drake Citation1998; Juergensmeyer Citation2003; Wood Citation2010; Wood Citation2014; Pearlman Citation2011.

12 For example, see Sharp Citation1973; Ackerman and Kruegler Citation1993; Nepstad Citation2011.

13 For example, see Chenoweth and Stephan Citation2012; Cunningham Citation2013; Asal et al. Citation2013; Braithwaite, Braithwaite, and Kucik Citation2015; Chenoweth and Ulfelder Citation2017; Cunningham, Dahl, and Fruge Citation2017.

14 Although these models explore the interactions between the state and the dissidents, they assume that the state’s repression policy is exogenous. Pierskalla (Citation2010) and Ritter (Citation2014) are two recent studies that endogenize state repression policy, too.

15 Here, for simplicity, I assume that the movement already resolved its collective action problem. Since I study the methods of resistance adopted by opposition movements that already collectively challenged the state, discussing how they overcome their collective action problem is not within the scope of this study.

16 We can assume that nonviolent movements are more disruptive ceteris paribus, but then discussing why the movements choose nonviolent tactics would be redundant. However, it would be scientifically more interesting if we explore the underlying mechanisms through which the movements choose nonviolent methods of resistance while violent tactics are more coercive.

17 For example, see Chenoweth and Stephan (Citation2012).

18 There have been hunger strikes historically that have resulted in mobilizing the masses. For instance, the 1981 hunger strike of Irish republican prisoners is a good example. Nevertheless, small strikes are nearly unlikely to be directly effective in changing the state’s policies, especially in non-democratic regimes.

20 Chenoweth and Shay Citation2019.

21 Beissinger Citation1998.

22 For more details on the method, see https://www.stata.com/manuals14/memelogit.pdf.

23 For example: Arendt Citation1970; Crenshaw Citation1981; Della Porta and Tarrow Citation1986.

24 See Heckman (Citation1976; Citation1979) for detailed mathammtical discussions of the sample selection problem.

References

- Ackerman, P., and C. Kruegler. 1993. Strategic Nonviolent Conflict: The Dynamics of People Power in the Twentieth Century. Westport, Conn: Praeger. 392 pp.

- Amemiya, T. 1977. “The Maximum Likelihood and the Nonlinear Three-Stage Least Squares Estimator in the General Nonlinear Simultaneous Equation Model.” Econometrica 45 (4): 955–968.

- Angrist, J. D., and J.-S. Pischke. 2009. Mostly Harmless Econometrics: An Empiricist’s Companion. 1st ed. Princeton: Princeton University Press. 392 pp.

- Arendt, H. 1970. On Violence. 1st ed. New York: Harcourt Brace Ja- vanovich. 120 pp.

- Asal, V., et al. 2013. “Gender Ideologies and Forms of Contentious Mobilization in the Middle East.” Journal of Peace Research 50 (3): 305–318.

- Asal, V., and R. Karl Rethemeyer. 2008. “The Nature of the Beast: Organizational Structures and the Lethality of Terrorist Attacks.” The Journal of Politics 70 (2): 437–449.

- Beck, N., J. N. Katz, and R. Tucker. 1998. “Taking Time Seriously: Time-Series-Cross-Section Analysis with a Binary Dependent Variable.” American Journal of Political Science 42 (4): 1260–1288.

- Beissinger, M. R. 1998. “Nationalist Violence and the State: Political Authority and Contentious Repertoires in the Former USSR.” Comparative Politics 30 (4): 401–422.

- Beissinger, M. R. 2009. “Nationalism and the Collapse of Soviet Communism.” Contemporary European History 18, 331–347.

- Bon, Le. 1898. The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications (Reprint in 2002)

- Braithwaite, A., J. M. Braithwaite, and J. Kucik. 2015. “The Conditioning Effect of Protest History on the Emulation of Nonviolent Conflict.” Journal of Peace Research 52 (6): 697–711.

- Braithwaite, J. M., and K. G. Cunningham. 2020. “When Organizations Rebel: Introducing the Foundations of Rebel Group Emergence (FORGE) Dataset.” International Studies Quarterly 64 (1): 183–193.

- Chenoweth, E., and K. Schock. 2015. “Do Contemporaneous Armed Challenges Affect the Outcomes of Mass Nonviolent Campaigns?” Mobilization: An International Quarterly 20 (4): 427–451.

- Chenoweth, E., and C. W. Shay. 2019. “NAVCO 2.1 Dataset.” Harvard Dataverse V2. doi:https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/MHOXDV.

- Chenoweth, E., and M. J. Stephan. 2012. Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict. Reprint ed. New York: Columbia University Press. 320 pp.

- Chenoweth, E., and J. Ulfelder. 2017. “Can Structural Conditions Explain the Onset of Nonviolent Uprisings?” Journal of Conflict Resolution 61 (2): 298–324.

- Cosgrove, B. 2013. LIFE and Civil Rights: Anatomy of a Protest, Virginia, 1960. Time. url: http://time.com/3638319/life-and-civil-rights-anatomy-of-a-protest- virginia-1960/ (visited on 08/27/2017).

- Crenshaw, M. 1981. “The Causes of Terrorism.” Comparative Politics 13 (4): 379–399.

- Cunningham, K. G. 2013. “Understanding Strategic Choice: The Determinants of Civil war and Nonviolent Campaign in Self-Determination Disputes.” Journal of Peace Research 50 (3): 291–304.

- Cunningham, K. G., and E. Beaulieu. 2010. “Dissent, Repression, and Inconsistency.” In Rethinking Violence: States and Non-State Actors in Conflict, edited by E. Chenoweth and A. Lawrence. New ed, 173–196. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Cunningham, K. G., M. Dahl, and A. Fruge. 2017. “Strategies of Resistance: Diversification and Diffusion.” American Journal of Political Science 61 (3): 591–605.

- Davenport, C. 1996. “The Weight of the Past: Exploring Lagged Determinants of Political Repression.” Political Research Quarterly 49 (2): 377–403.

- Davenport, C. 2007. “State Repression and Political Order.” Annual Review of Political Science 10 (1): 1–23.

- Davenport, C. 2014. How Social Movements Die. Google-Books-ID: r56TBQAAQBAJ. Cam- bridge University Press. 367 pp.

- Della Porta, D., and S. Tarrow. 1986. “Unwanted Children: Political Violence and the Cycle of Protest in Italy, 1966–1973.” European Journal of Political Research 14 (5): 607–632.

- DeNardo, J. 1985. Power in Numbers: The Political Strategy of Protest and Rebellion. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. 286 pp.

- Drake, C. J. M. 1998. “The Role of Ideology in Terrorists’ Target Selection.” Terrorism and Political Violence 10 (2): 53–85.

- Eubank, W., and L. Weinberg. 2001. “Terrorism and Democracy: Perpetrators and Victims.” Terrorism and Political Violence 13 (1): 155–164.

- Fair, C. C. 2005. “Diaspora Involvement in Insurgencies: Insights from the Khalistan and Tamil Eelam Movements.” Nationalism and Ethnic Politics 11 (1): 125–156.

- Francisco, R. 2004. “After the Massacre: Mobilization in the Wake of Harsh Repression.” Mobilization: An International Quarterly 9 (2): 107–126.

- Gallo-Cruz, S. 2012, Jan. 1. “Organizing Global Nonviolence: The Growth and Spread of Nonviolent INGOS, 1948–2003.” In Nonviolent Conflict and Civil Resistance. Edited by Erickson Nepstad, S. and Kurtz, L. R., Vol. 34. 0 vols. Research in Social Movements, Conflicts and Change 34, 213–256. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Gurr, T. R. 1971. Why Men Rebel. Anv ed. Boulder, Colo: Routledge. 440 pp.

- Haines, Herbert H. (1984, Oct. 1). “Black Radicalization and the Funding of Civil Rights: 1957-1970”. Social Problems 32.1, 31–43.

- Hechter, M. 1995. “Explaining Nationalist Violence.” Nations and Nationalism 1 (1): 53–68.

- Heckman, J. 1976. “The Common Structure of Statistical Models of Truncation, Sample Selection and Limited Dependent Variables and a Simple Estimator for Such Models.” Annals of Economic and Social Measurement 5 (4): 475–492.

- Heckman, J. 1979. “Sample Selection Bias as a Specification Error.” Econometrica 47 (1): 153–161.

- Hegre, H., et al. 2001. “Toward a Democratic Civil Peace? Democracy, Political Change, and Civil War, 1816–1992.” American Political Science Review 95 (1): 33–48.

- Heijenoort, J. v. 2002. From Frege to Godel: A Source Book in Mathematical Logic, 1879-1931. Revised edition. Princeton; London: Princeton University Press. 72 pp.

- Henderson, C. W. 1991. “Conditions Affecting the Use of Political Repression.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 35 (1): 120–142.

- Hendrix, C. S., and S. Haggard. 2015. “Global Food Prices, Regime Type, and Urban Unrest in the Developing World.” Journal of Peace Research 52 (2): 143–157.

- Hibbs Jr, D. A. 1995. Mass Political Violence: A Cross-National Causal Analysis. 1st ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons Inc. 272 pp.

- Juergensmeyer, M. 2003. Terror in the Mind of God: The Global Rise of Religious Violence. 3rd ed., rev. and updated. Comparative studies in religion and society 13. Berkeley: University of California Press. 319 pp.

- Kalyvas, S. 2006. The Logic of Violence in Civil War. 1st ed. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. 510 pp.

- Karakaya, S. 2018. “Globalization and Contentious Politics: A Comparative Analysis of Nonviolent and Violent Campaigns.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 35 (4): 315–335.

- King, G., J. Pan, and M. E. Roberts. 2017. “How the Chinese Government Fabricates Social Media Posts for Strategic Distraction, Not Engaged Argument.” American Political Science Review 111 (3): 484–501.

- Krain, M., and M. E. Myers. 1997. “Democracy and Civil war: A Note on the Democratic Peace Proposition.” International Interactions 23 (1): 109–118.

- Kuran, T. 1989. “Sparks and Prairie Fires: A Theory of Unanticipated Political Revolution.” Public Choice 61 (1): 41–74.

- Kuran, T. 1991. “Now out of Never: The Element of Surprise in the East European Revolution of 1989.” World Politics: A Quarterly Journal of International Relations 44, 7–48.

- Le Bon, G. 2002. The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications. (Reprint).

- Lichbach, M. I. 1987. “Deterrence or Escalation? The Puzzle of Aggregate Studies of Repression and Dissent.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 31 (2): 266–297.

- Marshall, M., and K. Jaggers. 2002. “Polity IV Project: Political Regime Characteristics and Transitions, 1800-2002”.

- Mason, T. D. 1996. “Insurgency, Counterinsurgency, and the Rational Peasant.” Public Choice 86 (1): 63–83.

- Mason, T. D., and D. A. Krane. 1989. “The Political Economy of Death Squads: Toward a Theory of the Impact of State-Sanctioned Terror.” International Studies Quarterly 33 (2): 175–198.

- Moore, W. H. 1998. “Repression and Dissent: Substitution, Context, and Timing.” American Journal of Political Science 42 (3): 851–873.

- Muller, E. N. 1985. “Income Inequality, Regime Repressiveness, and Political Violence.” American Sociological Review 50 (1): 47–61.

- Nepstad, S. E. 2011. Nonviolent Revolutions: Civil Resistance in the Late 20th Century.

- Pearlman, W. 2011. Violence, Nonviolence, and the Palestinian National Movement. Reprint ed. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. 302 pp.

- Pierskalla, J. H. 2010. “Protest, Deterrence, and Escalation: The Strategic Calculus of Government Repression.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 54 (1): 117–145.

- Poe, S. C., and C. Neal Tate. 1994. “Repression of Human Rights to Personal Integrity in the 1980s: A Global Analysis.” The American Political Science Review 88 (4): 853–872.

- Rasler, K. 1996. “Concessions, Repression, and Political Protest in the Iranian Revolution.” American Sociological Review 61 (1): 132–152.

- RezaeeDaryakenari, B., and P. Asadzade. 2020. “Learning About Principles or Prospects for Success? An Experimental Analysis of Information Support for Nonviolent Resistance.” Research & Politics 7 (2): 2053168020931693.

- Ritter, E. H. 2014. “Policy Disputes, Political Survival, and the Onset and Severity of State Repression.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 58 (1): 143–168.

- Ritter, E. H., and C. R. Conrad. 2016. “Preventing and Responding to Dissent: The Observational Challenges of Explaining Strategic Repression.” American Political Science Review 110 (1): 85–99.

- Roberts, A., and T. Ash. 2009, Nov. 2. Civil Resistance and Power Politics: The Experience of Nonviolent Action from Gandhi to the Present. 1st ed. Oxford England; New York: Oxford University Press. 412 pp.

- Rule, J. B. 1989, Aug. 14. Theories of Civil Violence. Berkeley: University of California Press. 482 pp.

- Schrodt, Philip. 2012. “Precedents, progress, and prospects in political event data.” International Interactions 38 (4): 546–569.

- Shadmehr, M., and P. Haschke. 2016. “Youth, Revolution, and Repression.” Economic Inquiry 54 (2): 778–793.

- Sharp, G. 1973, June 2. Power and Struggle. Boston, MA: Porter Sargent Publishers. 144 pp.

- Sighele, S. 1890. foule criminelle: ai de psychologie criminelle. Classiques des sciences sociales. Chicoutimi: J.-M. Tremblay. Accessed March 13, 2016. http://www.uqac.ca/zone30/Classiques_des_sciences_sociales/classiques/sighele_scipio/foule_criminelle/foule_criminelle.html.

- Skocpol, T. 1979, Feb. 28. States and Social Revolutions: A Comparative Analysis of France, Russia and China. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. 426 pp.

- Stukal, D., S. Sanovich, J. A. Tucker, and R. Bonneau. 2019. “For Whom the Bot Tolls: A Neural Networks Approach to Measuring Political Orientation of Twitter Bots in Russia.” SAGE Open 9 (2): 2158244019827715.

- Sullivan, C. M., and C. Davenport. 2017. “The Rebel Alliance Strikes Back: Understanding the Politics of Backlash Mobilization.” Mobilization: An International Quarterly 22 (1): 39–56.

- Tarde, G. 1968. Penal Philosophy, trans. R. Howell. Montclair, NJ: Patterson Smith.

- Tarrow, S. G. 1989. Struggle, politics, and reform: collective action, social movements and cycles of protest. In collab. with Cornell University. Cornell studies in international affairs no. 21. Ithaca, N.Y.: Center for International Studies, Cornell University. 120 pp.

- Tarrow, S. 1993. “Cycles of Collective Action: Between Moments of Madness and the Repertoire of Contention.” Social Science History 17 (2): 281–307.

- Tarrow, S. G. 1994. Power in Movement: Social Movements and Contentious Politics. Cambridge Studies in Comparative Politics. Cambridge, U.K.; New York: Cambridge University Press. 271 pp.

- Tilly, C. 1977. From Mobilization to Revolution. Ann Arbor, Michigan: Univeristy of Michigan.

- Tilly, C. 1978, August 10. From Mobilization to Revolution. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. 349 pp.

- Tilly, C. 2003. The Politics of Collective Violence. Cambridge Studies in Contentious Politics. Cam- bridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. 276 pp.

- Tilly, C., and S. Tarrow. 2006, Aug. 15. Contentious Politics. 1st ed. Oxford, Oxon, UK: Oxford University Press. 224 pp.

- Vreeland, J. R. 2008, June 1. “The Effect of Political Regime on Civil War Unpacking Anocracy.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 52 (3): 401–425.

- Wasow, Omar. 2020. “Agenda seeding: How 1960s black protests moved elites, public opinion and voting.” American Political Science 114 (3): 638–659.

- Weinstein, J. M. 2006, Oct. 9. Inside Rebellion: The Politics of Insurgent Violence. 1st ed. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. 430 pp.

- Wood, R. M. 2010. “Rebel Capability and Strategic Violence Against Civilians.” Journal of Peace Research 47 (5): 601–614.

- Wood, R. M. 2014. “From Loss to Looting? Battlefield Costs and Rebel Incentives for Violence.” International Organization 68 (4): 979–999.