?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

The distinction between constitutional monarchies and republics constitutes a striking divide in how modern democracies are institutionalized. However, the lack of data about citizens' preferences for a monarchic or republican model of democracy has hindered the analysis of public opinion about this topic. This research note introduces a comprehensive survey that gauges citizens' attitudes towards the monarchy in Spain. The survey was fielded in late 2020 and provides unique information such as respondents' preferences about different models of democracy, how they define an ideal monarch, and their evaluations of whether current and former Spanish kings live up to these ideals. We first highlight the unique features of the dataset and provide a detailed account of the variables included. We then illustrate the potential of this survey for the study of political culture through descriptive analyses of some of the key variables included in the dataset.

1. Introduction

Free and fair elections, the rule of law, and civil liberties are basic attributes of any democracy (Dahl Citation1971; Held Citation2006). Modern democracies are unthinkable without them. In fact, most Europeans agree that these are fundamental attributes in any democratic system (Hernández Citation2016). However, beyond these minimum requirements, democracies can be institutionalized in different ways, and citizens might not agree on the particular model of democracy that is best for their countries (Ferrín and Hernández Citation2021).

The distinction between constitutional monarchies and republics constitutes a striking divide in how modern democracies are institutionalized (Lijphart Citation2012, 127–129). While in most countries the head of the state is directly elected or appointed by the legislature, in 17 out of the 99 countries classified as democracies by Polity IV, he or she reaches office either by hereditary succession or by being appointed by a royal council.Footnote1

Public opinion data about citizens' preferences regarding other divides between models of democracy, such as the one confronting consensus and majoritarian political systems, has recently become available (Ferrín and Kriesi Citation2016). There is, however, a paucity of data about citizens' preferences for monarchic or republican models of democracy. Mass-media and polling firms like YouGov regularly field survey questions about the monarchy in countries such as the UK, the Netherlands, and Spain. However, this data is generally not available to researchers, and their questions are different than those commonly asked in political culture surveys. Academically-oriented surveys, like the British Social Attitudes Survey or those conducted by the Spanish National Sociological Center (CIS), have in the past asked some questions about the monarchy. However, their scattered and standalone nature prevents a systematic analysis of attitudes towards this particular model of democracy. Given this lack of data, it is not surprising to find only a handful of studies on attitudes towards monarchies, monarchs, and their main correlates (Blumler et al. Citation1971; Boynton and Loewenberg Citation1974; Rose and Kavanagh Citation1976; Bean Citation1993; García del Soto Citation1999; Davidson, Fry, and Jarvis Citation2006; Garrido, Martínez, and Mora Citation2020).

This research note introduces a survey that gauges citizens' attitudes towards the monarchy in Spain. The survey, fielded in September-October 2020, provides information such as respondents' preferences about different models of democracy, how they define an ideal monarch, or their evaluations of whether current and former Spanish kings live up to these ideals (among many others). Taken together with the extensive socio-demographic and political background variables included in the dataset, this survey will be an excellent resource for researchers aiming to systematically analyze the foundations of citizens' attitudes towards the monarchy and Spain's political culture.

2. Institutional background: the Spanish monarchy

The Spanish Constitution, ratified through a referendum on December 1978, establishes that the Kingdom of Spain is a parliamentary monarchy and that the Crown shall be inherited by the successors of Juan Carlos de Borbon. The monarch is the head of state, but in practical terms his duties are ceremonial. Thus far, only two kings have reigned under the 1978 constitution: Juan Carlos de Borbón and his son Felipe.

After being directly designated as his successor by the dictator Francisco Franco in 1969, Juan Carlos ascended to the throne two days after the death of the dictator in 1975 (44 years after his grandfather, King Alfonso XII, was deposed due to the instauration of the Spanish Second Republic).Footnote2 Juan Carlos I reigned until 2014, when he abdicated the throne in favour of his son Felipe VI. The abdication occurred in the aftermath of the 2008–2014 financial crisis, which fuelled Spaniards' distrust in political institutions (Muro and Vidal Citation2017), including the monarchy.Footnote3 Trust in the monarchy, measured on a 0-10 scale through CIS surveys, declined from 7.46 in March 1994 to a record low score of 3.7 in April 2013.Footnote4 This precipitous decline in the popularity of the Spanish Monarchy and Juan Carlos's abdication occurred amidst a series of scandals involving different members of the Royal Family. For example, in 2012 Juan Carlos was harshly criticized for participating in an elephant-hunting trip to Africa, and in 2013 Juan Carlos's daughter was indicted for tax fraud.

The survey fieldwork took place in September-October 2020, during the sixth year of King Felipe's reign, and some months after the publication of information about new scandals involving the Royal Family. In June 2020, for instance, prosecutors from Spain's Supreme Court launched an investigation into a series of kickback payments allegedly received by Juan Carlos for a contract to build a high-speed train to Mecca. In August 2020, Juan Carlos left Spain and relocated to the United Arab Emirates.

These recent events have generated a debate about the Spanish monarchy and have raised pressure to reform this institution. In fact, these developments, as well as Spain's territorial tensions, have led to an increasing politicization and contestation of this institution, which is mainly articulated by left-wing parties like Podemos or peripheral nationalist parties (e.g. Catalan and Basque nationalists). Many of these political parties openly advocate for the elimination of the monarchy and its replacement by a republic.

3. The dataset

The dataset includes 115 variables that can be grouped into four blocks: (i) socio-demographic; (ii) background political attitudes and behaviour; (iii) political regime preferences and evaluations; and (iv) Spanish institutions and monarchy. Table lists all the variables included in the dataset, as well as their corresponding survey questions. The dataset, as well as all the original survey documentation, are available in semicolon delimited and tabular formats at the Harvard Dataverse https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/H6GGZA (see Table C1 in Appendix C).Footnote5 Below we describe the dataset's key features and variables.

Table 1. Variables included in the dataset by topic.

3.1. Socio-demographic variables

Section 1 on socio-demographic characteristics provides detailed information about individuals' households and family backgrounds. Individuals’ variables include age, gender, level of education, professional status, and occupation. As for household information, the survey asks for the size of the household and the professional status, occupation, and highest level of education (if different than the respondent's) of the breadwinner. Finally, family background is captured through the level of education of the respondent's father and mother. The variables from this block are relevant to examine the socio-demographic bases of support for the monarchy. For example, both gender and age were known to affect support for the monarchy in the past (García del Soto Citation1999). More recent studies analyzing trust in the monarchy have focused on other demographic correlates of support for the monarchy such as education or social class (Garrido, Martínez, and Mora Citation2020). As we highlight below, some socio-demographic divides (e.g. generational) might be particularly relevant to understand the foundations of citizens' attitudes toward the monarchy.

3.2. Political attitudes and behaviour

The block on background political attitudes and behaviour includes some key variable to analyze the correlates of regime support: first, variables related to individuals' political interest, knowledge, and information; second, variables that capture respondents' self-placement in the ideological (left-right), cultural (GAL-TAN), and territorial (regional centralization-decentralization) dimensions; and third, variables related to respondents' electoral behaviour, as well as their political socialization. The variables from this block will, for example, allow researchers to analyze to what extent support for the monarchy is polarized along partisan, ideological and territorial divides. Ideological and territorial divides in support for the monarchy might be particularly relevant in Spain, since the Spanish monarchy was initially re-established during Franco's dictatorship, which was characterized by a strong repression of leftist and peripheral nationalist ideologies (Balcells and Villamil Citation2020).Footnote6

3.3. Political regime preferences and evaluations

In order to understand the foundations of support for the monarchy, the dataset contains detailed information about political regime preferences and evaluations. First, support for autocratic and technocratic regimes is captured through two standard questions from the World Values Survey (WVS). To measure support for democracy, the dataset includes two variables gauging overt support and satisfaction with democracy, which are based on those asked in the European Social Survey (ESS).

In a key innovation with respect to other datasets, this survey includes a variable that captures the specific type of democracy citizens prefer: a republic or a parliamentary monarchy. To capture individuals' general support for one or the other model of democracy, we instructed respondents to avoid thinking about Spain or any other country when answering this particular question (this is the approach adopted in other surveys such as the ESS to measure abstract support for different models of democracy). Overall, these variables will allow researchers to analyze how support for a republic or a monarchy relates to democratic, autocratic, and technocratic regime preferences, which is a key issue that was neglected by the few existing studies that analyzed attitudes toward monarchies.

3.4. Spanish institutions and monarchy

Most (66) of the dataset's variables are directly related to the monarchy. A first group of variables captures respondents' evaluations of the functioning of the Spanish monarchy, as well as their trust in this institution. The evaluation of the functioning of this institution is captured through a question asking respondents about their satisfaction with the Spanish monarchy, which mirrors the question that we ask in the previous block to gauge their satisfaction with democracy through a standard question that is often used in the political culture literature to analyze citizens' evaluations of this political regime. Moreover, to allow for comparisons, political trust is measured through a battery of questions that, beyond the monarchy, also covers other relevant political institutions. This battery is based on the one that the CIS fielded to measure trust in the monarchy and other political institutions until 2015. In Table A2 of the Appendix we document which of the questions of this block had already been asked by the CIS, and we provide the question code in the CIS database so that interested researchers can exploit this comparability between questions.Footnote7

The dataset also contains retrospective and prospective information about respondents' behaviour in referenda related to the monarchy. A first variable captures how respondents voted in the 1978 Constitutional referendum, which institutionalized Spain's constitutional monarchy. For those who were too young to have voted in this referendum, we include information on how they would have voted. Second, we include a series of variables gauging respondents' opinions about whether a referendum should be held in Spain to decide whether the country should remain a monarchy or become a republic; how they would vote in such a referendum; which position they think would win; and the type of republic they would prefer if Spain were to become one.

Another set of variables measures respondents' evaluations of specific members of the Royal Family: King Felipe IV, Queen Letizia, emeritus King Juan Carlos I, and emeritus Queen Sofia. For everyone except former Queen Sofia, the dataset contains information about where respondents position them in the ideological (left-right) and territorial (centralization-decentalization) dimensions. Given the historical origins of the Spanish monarchy (see above), as well as the rising politicization of this institution by left-wing and peripheral nationalist parties, it is of great relevance to analyze whether citizens perceive that the members of the Royal Family take a clear stance in these ideological and territorial dimensions. While this is interesting in and of itself, it will also be of relevance to explain any potential ideological or territorial divides in support for the monarchy. In the case of Juan Carlos and Felipe, the database also includes variables gauging respondents' evaluations of their performance during specific periods and events (e.g. Juan Carlos's actions during the 1981 attempted coup d'état).

To gain further insight on the foundations of citizens' support for the monarchy, the dataset also includes a series of variables about which traits, such as political neutrality, respondents think are important for a monarch to have. Respondents were then asked to evaluate to what extent former king Juan Carlos and current king Felipe possess these traits. These variables can be used to evaluate the mismatch between respondents’ ideal monarch and their evaluations of current and former Spanish kings, and how this disconnect might relate to the perceived legitimacy of the monarchy (see Ferrín and Kriesi Citation2016 for a similar approach applied to the measurement of democratic legitimacy)

Finally, the dataset also includes variables on changes respondents would like to see in the monarchy, as well as information about whether they agree with certain statements commonly made about the monarchy. Moreover, two additional variables capture respondents' opinions about whether king Felipe IV knew or benefited from the kickbacks allegedly received by his father Juan Carlos.

4. Survey design

4.1. Sample

The survey was fielded online through the panel of the commercial firm Cint. Fieldwork operations were managed by the commercial firm 40dB. At the time of the fieldwork, Cint had approximately 620,000 active panelists in Spain.

The final sample includes 3000 Spanish respondents aged 16 and over. Cint panelists were surveyed by means of quota-sampling using age, sex, region, size of the municipality, and socioeconomic status quotas.Footnote8 The targets for each of these quotas were set to be representative of these characteristics in the Spanish population. The age quota comprises the following age brackets: 16–17, 18–24, 25–34, 35–44, 45–54, 55–64, and 65 and over. The socioeconomic status quota, and the corresponding variable included in the dataset, follows the definition and standards of the Spanish Association for Media Research (AIMC by its acronym in Spanish). This is a complex categorization that combines information about the household's main breadwinner (highest level of education, professional status and occupation) and the characteristics of the household (household size and number of income earners). These elements are combined to rank individuals by their socioeconomic status. Individuals are classified in one of seven groups that range from A1 (highest socioeconomic status) to E2 (lowest socioeconomic status). Table A1 in Appendix A provides further information about all the quotas.

4.2. Survey administration

Fieldwork began on September 21, 2020, and ended on October 5, 2020. Respondents were invited to take the survey by email. Participants who accepted the invitation were then provided with additional information about the survey and were asked to indicate their consent before any questions were administered. The questionnaire was optimized for computer-assisted web interviewing. All questions were forced-choice (i.e. respondents could not progress without answering), but most questions included at least one non-response category (e.g. ‘I don't know’). We used a trap question to screen out inattentive respondents (see Appendix A). Moreover, for political knowledge items (questions p33 and p34), we limited the response time to 20 seconds and recorded a non-answer if respondents failed to answer the question within the time limit.

Table summarizes some relevant fieldwork metrics. Based on these metrics, we estimate the survey absorption, participation and completion rates, which follow Callegaro and DiSogra (Citation2008). The absorption rate of 0.99 reflects the proportion of invitations to take the survey that reached the respondent (i.e. the email did not bounce back). The participation rate of 0.22 indicates the share of individuals who accepted the invitation to participate in the survey. The completion rate of 0.11 reflects the proportion of those who completed the survey among all the eligible panel members who were invited to take the survey.Footnote9 Compared to similar studies recently conducted in Spain, our completion rate is higher in some cases (Häusermann et al. Citation2020) and lower in others (Hernández and Pannico Citation2020; Torcal et al. Citation2020). In any case, in online surveys the completion rate should not be taken as a sign of the quality of the sample or panel but as an indication of the efficiency and business strategy of the panel provider (Willems, Van Ossenbruggen, and Vonk Citation2006; Callegaro and DiSogra Citation2008).

Table 2. Fieldwork metrics.

4.3. Weights

The dataset provides two design weights, both estimated through a raking ratio post-stratification procedure. The first weight (variable ponde in the dataset) is socio-demographic and aims to achieve representativeness in terms of age, sex, region, size of the municipality, and socioeconomic status. Hence, this weight adjusts for deviations between the final sample and the sampling quota targets (see Table A1 in Appendix A). The second weight (variable pondrecu in the dataset) adds partisanship into the calculation, measured as the party respondents voted for in the last general election, or for those under 18, the party they would have voted for. Figure A1 in Appendix A summarizes the distribution of these weights.

4.4. Validation

To validate the representativeness of the sample, we establish a comparison between the left-right self-placement of respondents in our survey (question p20) and in the latest round of the ESS fielded in Spain (round 9). The formulation and response categories of this question are very similar in our survey and in the ESS, thus providing a good basis for comparison. The ESS is well known for its strict sampling methods, it is conducted face to face, and its sample is representative of all persons aged 15 and over. While the ESS fieldwork was completed nine months earlier than ours, we would argue that there are no reasons to believe that the ideology of Spaniards might have significantly changed during this time frame (see Ares, Bürgisser, and Häusermann Citation2021).

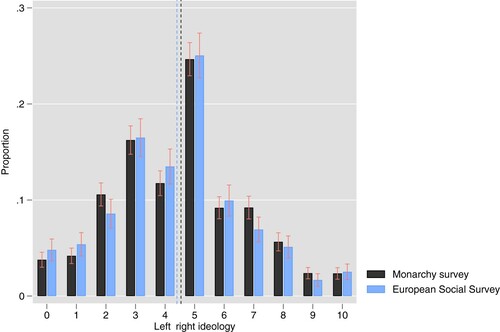

Figure summarizes this comparison. Data for the Monarchy survey are weighted using the socio-demographic (ponde) weight. ESS data are weighted using the post-stratification (pspwght) weight. The distribution of the self-placement in the left-right scale is very similar in both datasets. In fact, the mean placement is almost the same: 4.54 in the Monarchy survey and 4.40 in the ESS.

4.5. Fieldwork funding

The survey fieldwork was financed through a crowdfunding campaign. To design and launch the campaign, we partnered with 16 Spanish online media outlets grouped in the Independent Media Platform.Footnote10 The campaign was run on the crowdfunding platform Goteo.org.

The crowdfunding campaign launched on September 7, 2020, and ended on September 8, when 1965 backers had donated the 32,000 euros required to complete this project and field the survey. While crowdfunding for scientific research is not new, it is less common in the social sciences (Sauermann, Franzoni, and Shafi Citation2019). In fact, to our knowledge this is the largest crowdfunding campaign ever conducted in Spain for fielding a scientific survey.

5. Using the dataset

Next, we describe some patterns uncovered through this survey in order to illustrate its potential for researchers interested in the analysis of political culture. Specifically, we focus on two particular issues that may be of interest to researchers beyond the Spanish case: intergenerational and ideological polarization in citizens' opinions about the monarchy. Even at a time when many European democracies are strongly polarized (Reiljan Citation2020), we would still expect neutral political figures such as monarchs to generate consensus across political divides. Is this, however, the case?

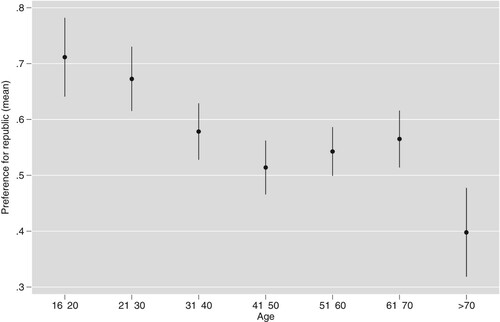

In Figure we examine respondents' generic preference for a republic or a constitutional monarchy.Footnote11 Respondents were asked what kind of democracy they thought was better: a republic or a parliamentary monarchy (question p6). Overall, citizens slightly favour a republican model of democracy. The mean of this variable, in which those favouring a republic are coded as 1 and those supporting a parliamentary monarchy are coded as 0, equals 0.561 (the mean equals 0.559 if only those aged 18 and over are included in the analysis).Footnote12 The results summarized in Figure reveal a clear generational divide. While those younger than 30 are clearly in favour of a republic, a majority of those older than 70 support a constitutional monarchy. There seems to be no consensus across generations as to which is the best model of democracy: a republic or a monarchy. With this dataset, future studies will be able to evaluate whether these inter-generational differences have an evaluative or cultural basis (see Mishler and Rose Citation2001).

Figure 2. Preference for republic (vs. monarchy) and age.

Note: Entries report mean support for a republic (=1) instead of a parliamentary monarchy (=0) and 95% confidence intervals. N=2503.

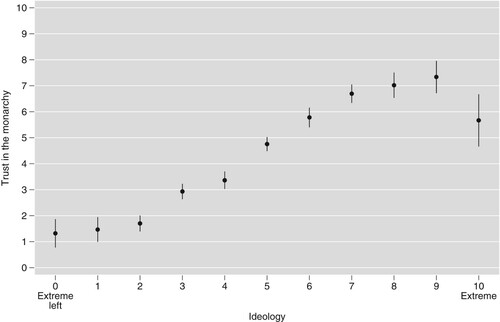

We now turn to examine respondents' trust in the Spanish monarchy, which is measured on scale ranging from 0, indicating no trust at all, to 10, indicating complete trust (question p8). The average level of trust in the Monarchy is 4.13 (the average equals 4.16 if only those aged 18 and over are included in the analysis). However, Figure reveals that trust varies significantly with ideology. While those on the left are extremely distrustful of the institution, trust in the monarchy steadily increases as one move towards the right. The only exception are those on the extreme right, who appear to be slightly less trustful than many of those on the right side of the ideological spectrum. This might be explained by a more skeptical (and populist) outlook towards all political institutions among those on the extreme right. In any case, the results reveal a strong ideological polarization in terms of trust in the Spanish monarchy.Footnote13

Figure 3. Trust in the monarchy and left-right ideology.

Note: Entries report mean trust in the monarchy by ideology and 95% confidence intervals.

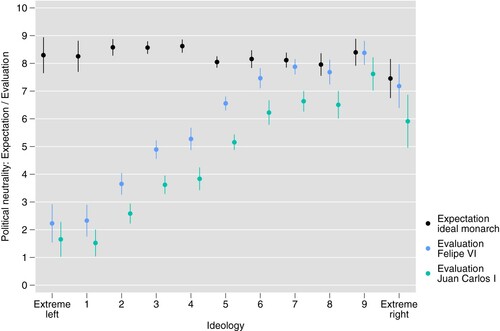

This divide between ideological camps might be rooted in differing expectations about the behaviour of monarchs. Our dataset will allow researchers to thoroughly examine citizens' expectations about the traits and behaviour of an ideal monarch, as well as their perceptions of how Spanish monarchs might have deviated from this ideal. In Figure , for example, we focus on political neutrality, a key trait of any monarch. This figure first shows to what extent respondents think that being politically neutral is important for a monarch to fulfill his duties (question p18R1). This expectation about an ideal monarch is measured on a scale from 0 (not at all important) to 10 (very important). The figure also plots respondents' evaluations of the former King Juan Carlos I and the current King Felipe VI political neutrality. These evaluations are also measured on a 0-10 scale, with 0 indicating that they are not at all neutral and 10 that they are fully neutral.

Figure 4. Expectations and evaluations about political neutrality of monarchs and left-right ideology.

Note: Entries report mean expectation/evaluation by ideology and 95% confidence intervals.

Figure reveals that, independent of their ideology, most citizens consider that it is very important that monarchs be politically neutral (black dots and whiskers). Conversely, there are large differences in how citizens evaluate the political neutrality of the former (Juan Carlos I) and current (Felipe VI) Spanish kings depending on their ideology. Among those on the right, their expectation of political neutrality is consistently met by the current monarch Felipe VI. In the case of Juan Carlos I, all respondents evaluate his political neutrality more negatively than that of his son Felipe, and even among those with a right-wing ideology there is a slight mismatch between their expectations and evaluations of Juan Carlos's neutrality. As we move towards the left, tough, there is a growing and substantial mismatch between the expected political neutrality of an ideal monarch and perceptions of Juan Carlos I's and Felipe VI's neutrality. This large mismatch between expectations and evaluations might be one of the reasons why those on the left have less trust in the monarchy. Our dataset includes information about seven additional traits of monarchs that, in light of this evidence, might prove useful in assessing the evaluative foundations of support for the monarchy.

6. Conclusion

Western democracies are facing relevant challenges such as declining support for liberal values, a populist upsurge, heightened political polarization, or increasing demands for technocratic governance (Foa and Mounk Citation2017; Reiljan Citation2020; Bertsou and Caramani Citation2020), and Spain has not been immune to these developments (Orriols and Cordero Citation2016; Amat et al. Citation2020; Turnbull-Dugarte, Rama, and Santana Citation2020). This context presents both a challenge and a possible opportunity for monarchies. As a unifying, non-partisan representative of the state, a constitutional monarch can bring stability and impartiality (Lijphart Citation2012; Bulmer Citation2014). However, at the same time, some might consider that monarchies are not fully compatible with modern democratic values (Bulmer Citation2014). It is an open question whether and why citizens might still support a model of democracy where the head of state reaches office by hereditary succession.

Our dataset allows researchers to address this and many other questions related to this under-researched model of democracy. It is the most comprehensive publicly available source on individuals' opinions about the monarchy. The results presented above also highlight how researchers interested in other topical issues, such as political polarization, will also benefit from this dataset. While this paper does not incorporate all the results from our survey, the analyses reveal a striking level of polarization around the monarchy along generational, ideological, partisan, and territorial divides. Together with other datasets recently made publicly available (e.g. Torcal et al. Citation2020), this data allows researchers to explore new questions about Spain's political culture. Moreover, from a comparative perspective, these data complements other national and international efforts to examine individuals' understandings and evaluations of democracy's many dimensions (e.g. rounds 6 and 10 of the ESS).

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (228.2 KB)Acknowledgments

The survey on the Spanish monarchy was generously funded by 1965 backers who donated the money to complete the fieldwork through a crowdfunding campaign launched by 16 Spanish online media outlets grouped in the Independent Media Platform (“Plataforma de Medios Independientes”). We would also like to thank Belén Barreiro, Stephan Zhao and Laura Bejarano for their valuable input during the design of the questionnaire, as well as the editors of Political Research Exchange and three anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions on the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Based on the V-Dem dataset (v10). A country is considered democratic if it receives a score of six or higher in the Polity IV index.

2 See Bernecker (Citation1996) and Zugasti (Citation2005) for an overview about the reinstatement of the Spanish Monarchy.

3 Muro and Vidal (Citation2017) show that southern European countries experienced a decline in trust in political institutions – parliament, government and political parties– following the Great Recession. All the institutions suffered a similar decrease in trust, although the baseline level of confidence in political parties was clearly below that of the parliament and the government.

4 In April 2015, the CIS measured trust in the monarchy for the last time, and the score was 3.72

5 The dataset DOI is 10.7910/DVN/H6GGZA

6 Garrido, Martínez, and Mora (Citation2020), in fact, show that trust in the Spanish monarchy is substantially higher among those with a right-wing ideology.

7 Table A2 reveals that, beyond the institutional trust battery, only three other questions from this block have been included in CIS surveys. Hence, our dataset will open up unique research avenues thanks to the inclusion of new variables.

8 Researchers using the dataset must take into account that our sample includes respondents aged 16 and 17. While this is common in leading surveys in the field (e.g. the ESS), the Spanish CIS generally only includes respondents aged 18 and over. This might be relevant at the time of establishing comparisons between our dataset and other surveys conducted by the CIS, which might not include these young respondents.

9 The completion rate is computed following AARPOR response-rate (RR5) standard definition: , where

the number of completed interviews,

the number of partial (non-completed) interviews,

the number of refusals and break-offs,

the number of non-contacts,

the number of non-completed interviews due to other reasons

10 The media outlets that participate in the Independent Media Platform are: Alternativas economicas, Carne Cruda, Catalunya Plural, Critic, CTXT, Cuartopoder, El Salto, La Marea, La Voz del Sur, Luzes, Mongolia, Norte, Nueva Tribuna, Pikara Magazine, Praza, Público

11 All the results discussed in this section are weighted using the socio-demographic ponde weight.

12 16.6 percent of respondents declared that they didn't know, and are coded as missing.

13 If instead of analyzing the ideological divide through the self-location of respondents on the left-right dimension we assess the levels of trust in the monarchy according to the party respondents voted for in the last General Election, the data reveals a similar and strong divide. Supporters of parties located on the right of the ideological spectrum have higher levels of trust than those of left-wing and, especially, peripheral nationalist parties. The results of these analyses can be found in Figure B1.

References

- Amat, F., A. Arenas, A. Falcó-Gimeno, and J. Muñoz. 2020. “Pandemics Meet Democracy. Experimental Evidence from the COVID-19 Crisis in Spain.” SocArXiv preprint.

- Ares, M., R. Bürgisser, and S. Häusermann. 2021. “Attitudinal Polarization Towards the Redistributive Role of the State in the Wake of the COVID-19 Crisis.” Journal of Elections Public Opinion and Parties. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17457289.2021.1924736.

- Balcells, L., and F. Villamil. 2020. “The Double Logic of Internal Purges: New Evidence From Francoist Spain.” Nationalism and Ethnic Politics 26 (3): 260–278. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13537113.2020.1795451.

- Bean, C. 1993. “Public Attitudes on the Monarchy-Republic Issue.” Australian Journal of Political Science 28 (4): 190–206. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00323269308402275.

- Bernecker, W. L. 1996. “El papel político del Rey Juan Carlos en la transición.” Revista de estudios políticos 92: 113–137.

- Bertsou, E., and D. Caramani. 2020. “People Haven't Had Enough of Experts: Technocratic Attitudes Among Citizens in Nine European Democracies.” American Journal of Political Science. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12554.

- Blumler, J. G., J. R. Brown, A. J. Ewbank, and T. J. Nossiter. 1971. “Attitudes to the Monarchy: Their Structure and Development During a Ceremonial Occasion.” Political Studies 19 (2): 149–171. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.1971.tb00667.x.

- Boynton, G. R., and G. Loewenberg. 1974. “The Decay of Support for Monarchy and the Hitler Regime in the Federal Republic of Germany.” British Journal of Political Science 4 (4): 453–488. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123400009662.

- Bulmer, E. 2014. Constitutional Monarchs in Parliamentary Democracies. International IDEA Constitution-Building Primer 7.

- Callegaro, M., and C. DiSogra. 2008. “Computing Response Metrics for Online Panels.” Public Opinion Quarterly 72 (5): 1008–1032. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfn065.

- Dahl, R. A. 1971. Polyarchy: Participation and Opposition. New Haven, London: Yale University Press.

- Davidson, S., T. R. L. Fry, and K. Jarvis. 2006. “Direct Democracy in Australia: Voter Behavior in the Choice Between Constitutional Monarchy and a Republic.” European Journal of Political Economy 22 (4): 862–873. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2005.11.001.

- Ferrín, M., and E. Hernández. 2021. “Preferences for Consensus and Majoritarian Democracy: Long- and Short-term Influences.” European Political Science Review 13 (2): 209–225. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773921000047.

- Ferrín, M., and H. Kriesi. 2016. “Introduction: Democracy – The Veredict of Europeans.” In How Europeans View and Evaluate Democracy?, edited by M. Ferrín, and H. Kriesi. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Foa, R. S., and Y. Mounk. 2017. “The Signs of Deconsolidation.” Journal of Democracy 28 (1): 5–15. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2017.0000.

- García del Soto, A. 1999. “Representaciones sociales y fundamentos básicos de la cultura política: opiniones intergeneracionales sobre la monarquía española actual.” PhD thesis, Instituto Juan March de Estudios e Investigaciones, Madrid.

- Garrido, A., M. A. Martínez, and A. Mora. 2020. “Monarchy and Public Opinion in Spain During the Crisis: The Performance of An Unaccountable Institution Under Stress.” Revista Española de Ciencia Política 52: 121–145. doi:https://doi.org/10.21308/recp.

- Häusermann, S., M. Ares, M. Enggist, and M. Pinggera. 2020. Mass Public Attitudes on Social Policy Priorities and Reforms in Western Europe. WELFAREPRIORITIES dataset 2020. Welfarepriorities Working Paper Series, n°1/20.

- Held, D. 2006. Models of Democracy. 3rd ed. Cambridge: Polity.

- Hernández, E. 2016. “Europeans' Views of Democracy: The Core Elements of Democracy.” In How Europeans View and Evaluate Democracy, edited by M. Ferrín, and H. Kriesi. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hernández, E., and R. Pannico. 2020. “The Impact of EU Institutional Advertising on Public Support for European Integration.” European Union Politics 21 (4): 569–589. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116520935198.

- Lijphart, A. 2012. Patterns of Democracy: Government Forms and Performance in Thirty-Six Countries. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Mishler, W., and R. Rose. 2001. “What Are the Origins of Political Trust? Testing Institutional and Cultural Theories in Post-Communist Societies.” Comparative Political Studies 34 (1): 30–62. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414001034001002.

- Muro, D., and G. Vidal. 2017. “Political Mistrust in Southern Europe Since the Great Recession.” Mediterranean Politics 22 (2): 197–217. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13629395.2016.1168962.

- Orriols, L., and G. Cordero. 2016. “The Breakdown of the Spanish Two-Party System: The Upsurge of Podemos and Ciudadanos in the 2015 General Election.” South European Society and Politics 21 (4): 469–492. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13608746.2016.1198454.

- Reiljan, A. 2020. “‘Fear and Loathing Across Party Lines’ (also) in Europe: Affective Polarisation in European Party Systems.” European Journal of Political Research 59 (2) 376-396. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12351.

- Rose, R., and D. Kavanagh. 1976. “The Monarchy in Contemporary Political Culture.” Comparative Politics 8 (4): 548–576. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/421543.

- Sauermann, H., C. Franzoni, and K. Shafi. 2019. “Crowdfunding Scientific Research: Descriptive Insights and Correlates of Funding Success.” PLOS One 14 (1): Article ID e0208384.doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0208384.

- Torcal, M., A. Santana, E. Carty, and J. M. Comellas. 2020. “Political and Affective Polarisation in a Democracy in Crisis: The E-Dem Panel Survey Dataset (Spain, 2018–2019).” Data in Brief 32: Article ID 106059. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2020.106059.

- Turnbull-Dugarte, S. J., J. Rama, and A. Santana. 2020. “The Baskerville's Dog Suddenly Started Barking: Voting for VOX in the 2019 Spanish General Elections.” Political Research Exchange 2 (1): Article ID 1781543. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/2474736X.2020.1781543.

- Willems, P., R. Van Ossenbruggen, and T. Vonk. 2006. “The Effect of Panel Recruitment and Management on Research Results: A Study Across 19 On-Line Panels.” In Proceedings of the ESOMAR World Research Conference, Panel Research 2006, 79–99, Vol. 317.

- Zugasti, R. 2005. “The Francoist Legitimacy of the Spanish Monarchy: An Exercise of Journalistic Amnesia During the Transition to Democracy.” Communication & Society 18 (2): 141–168.